Piero di Cosimo is one of the most distinctive personalities of the Florentine Renaissance. He was a contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli, and while he was to some extent influenced by both of them, his work remains immediately recognizable as something different, and stranger, than those of his better-known contemporaries. Vasari’s life of Piero is one of the more memorable in the Vite, pairing Piero’s strange works with the artist’s unorthodox personality.

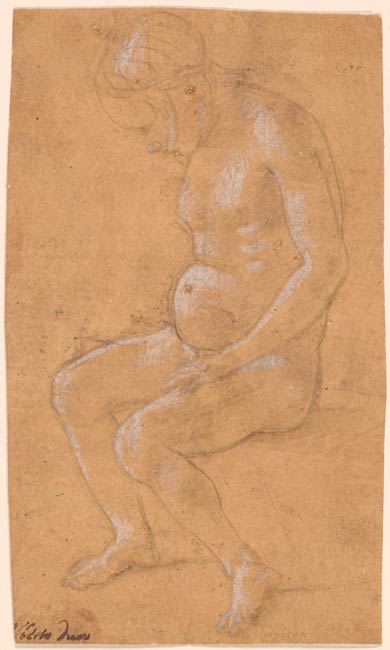

Piero was trained in Florence by Cosimo Rosselli (and adopted his name from his master), but one of his key formative experiences came when he accompanied his master to Rome, when Rosselli was to paint frescoes on the walls of the Sistine Chapel. There, Piero seems to have been particularly fascinated with the works of Luca Signorelli (see 1965.15), who was also then at work on the chapel. Signorelli’s influence is clear in the distinctive figure types that Piero thereafter developed. These types feature thin limbs and prominent stomachs, such as can be seen in the present drawing. The technique of the drawing remains, though, fully Florentine and compares to metalpoint sketches by Filippino Lippi (such as II, 72 and 1951.1) or Davide Ghirlandaio.

In a review of the 2015 Piero exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Peter Schjeldahl succinctly observed that “the most uncanny quality of Piero’s art . . . is the seductive expressiveness of characters who seem neither quite real nor merely imagined.”1 This felicitous description could be aptly applied to the Seated Nude. On the one hand, it fits into a tradition of model-book nudes—idealized but also slightly abstracted studies of the human form—in a tradition stretching from the fourteenth century up to the time of Piero’s slightly older contemporaries. There is something immediate about the figure, however, something that seems more like a study drawn from a live model, and the drawing thus evokes the new age of Florentine art in which paintings were based upon figure studies, as seen for example in the work of Andrea del Sarto, Piero’s student (see I, 30 and IV, 14). The drawing thus represents not only Piero’s work but also that key moment in the years leading up to 1500 that marks the shift from the Early Renaissance to the High Renaissance. Piero’s strong artistic personality complicates the matter, of course, for even when studying figures from life he subjected them to his own eccentric vision of humanity.

Fewer than thirty drawings by Piero survive, and other than the six studies directly connected to his paintings, much of his drawn oeuvre remains contested.2 The present study, however, has been included in the two most recent studies of the artist, and the attribution has been endorsed by those who have written on Piero’s drawings in recent decades. Beyond the six connected sheets, it is perhaps the drawing most readily accepted as Piero’s work, so clearly representative is it of the artist’s individual style. It exhibits many of his familiar mannerisms, such as the lock of hair falling alongside the figure’s face3 and, as mentioned above, the slightly distended belly. Although the Seated Nude does not reappear directly in any of Piero’s paintings, the figure can be compared to those in two paintings in particular, the Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs (National Gallery, London) and the Return from the Hunt (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Comparison with these paintings would also suggest a date of ca. 1495–1505.4

—JJM

Footnotes:

- Schjeldahl 2015.

- The Morgan owns one additional drawing attributed to Piero, a damaged pen study of St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata, inv. 1980.56. Griswold accepted this as Piero’s work in New York 1997–98, no. 120, but it is catalogued as “Piero di Cosimo (?)” by Anna Forlani Tempesti in Florence 2015, 55–56. The drawing’s former owner, Janos Scholz, noted (in a letter that is kept with the Morgan’s curatorial files), “there is no other drawing in my collection which has more contradictory opinions about it by so-called experts as this one.”

- There is a similar motif in, for example, Piero’s drawing of A Girl in Profile, (Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. rf 1439 verso). See Florence 2015, no. 66.

- The London Battle is usually dated to the first decade of the sixteenth century, but the New York Hunting Scene and Return from the Hunt could be as early as 1488 and are usually dated to the 1490s (see Washington and London 2015, no. 5).

Inscribed at lower left, in pen and brown ink, "[A]lberto Duro."

Sagredo, Nicolò, 1606-1676, former owner.

Sagredo, Stefano, former owner.

Sagredo, Zaccaria, 1653-1729, former owner.

Sagredo, Gherado, -1738, former owner.

Sagredo, Cecilia Grimani Calergi, -1805, former owner.

Gordon, Margot, former owner.

Rhoda Eitel-Porter and and John Marciari, Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 2019, no. 26.

Selected references: New York 1996, no. 1; Geronimus 2006, 97, 309n133; Florence 2015, 51, no. 63.