First trained in Verona in the workshop of his father, Giovanni Ermanno, with whom he collaborated during the 1560s, Jacopo Ligozzi transferred to Florence in 1577, where he worked as court artist to Francesco I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. It is probable that before moving to Tuscany Ligozzi sojourned in Vienna, where he became acquainted with German printmaking and especially with the works of Dürer and Burgkmair that would prove particularly important in the development of his work.1 He had already earned a reputation for astoundingly lifelike drawings of fish and plants, and his main task in Florence was to make a comprehensive visual record of the botanical specimens of the Medici gardens in Florence and Pisa. From 1587 onward he increasingly worked on paintings and figurative drawings, the latter often with gold highlighting. In 1593 he left the employ of the Medici and thereafter primarily painted altarpieces for Florentine and Tuscan patrons. The refinement of Ligozzi’s drawing style and his erudite subject matter appealed to the sophisticated tastes of the courtly and educated elite for whom he worked.

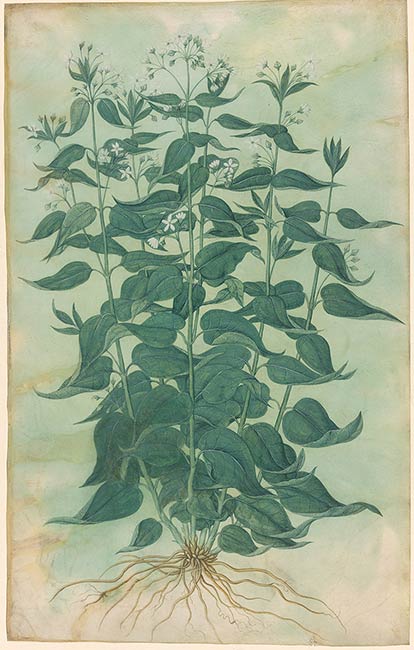

Ligozzi’s studies of animals and plants are of great scientific accuracy. The botanical specimens are clearly laid out to show all parts of the plant, including roots and flowers, but without any indication of spatial setting or other context. Most can be identified today. The plant shown here, Vincetoxicum officinale, or white swallowwort, is a European perennial, the root of which induces vomiting when ingested and—as the name vincetoxicum indicates—was formerly used as a counterpoison. Europe’s first botanical garden was founded by Cosimo I in Pisa in 1543 for the benefit of physicians and scholars as well as for the pure delectation of others. In 1545 a similar garden was established in Florence, the giardino dei semplici, also known as the giardino delle stalle. Following family tradition, Francesco I created the garden of the Casino di San Marco, where Ligozzi resided, as well as a garden in Pratolino. Attended by the foremost botanists of the age, the gardens were a seat of learning, featuring medicinal plants as well as exotic fruit from the New World.

Ligozzi’s accomplishments as a draftsman of botanical studies were remarked upon by the Bolognese naturalist Ulisse Aldovrandi (1522–1605), who was promised some of the artist’s drawings when he visited Florence in 1577. These are now in the University Library in Bologna. The great majority of Ligozzi’s extant natural history studies, however—129 in total—were made for Francesco I and are now in the collection of the Uffizi.2 Seventy-eight of these are botanicals, all on parchment; their refined quality and exquisite detail remain unsurpassed. In this example, some of the deep green, leathery leaves curl upward to reveal a silvery underside and a protruding network of veins. The elongated stems reach from freely floating branching roots and are topped with bursts of tiny white flowers, all captured with meticulous care.

A Botanical Specimen of Vincetoxicum officinale is one of at least three drawings said to be from the Houthakker collection that were on the art market in the early years of the twenty-first century. One is now at the Metropolitan Museum, New York; the other is part of the Jean Bonna Collection, Geneva.3 All three are on parchment and share a greenish aqueous background that probably was the result of water damage at a time when the sheets were stacked or bound together. The attribution of this group of drawings has not been unanimously accepted by Ligozzi experts, but the comparison to secure studies by the artist in Florence seems convincing, especially when bleeding of the color is taken into consideration for the changed aspect and potential loss of surface detail.

—REP

Footnotes:

- Ligozzi’s stay in Vienna is not documented, but critics agree that the artist sojourned in the Austrian city in the 1570s before moving to Florence in 1577. See Sergio Marinelli in Florence 2014, 21. For Ligozzi’s fascination with German prints, see Giorgio Marini in Florence 2014, 304–9, as well as No. 102 in this catalogue.

- Florence 2014, 296–97.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. 2004.435. See Bambach in New York 2010, no. 31, for the Metropolitan Museum sheet, and Strasser in New York and Edinburgh 2009, no. 23, for the Bonna collection drawing. The provenance of the Morgan sheet is not entirely clear. The drawing was shown by Richard L. Feigen & Co. and by Katrin Bellinger in around 2004 to 2010, but they may well have been acting on behalf of the eventual donor Dr. Werner Muensterberger. According to an information sheet on the drawing, thought to have been provided by Feigen & Co. in 2008, the most recent owner (presumably Muensterberger) claimed that he had acquired the sheet in Florence after the 1966 flood directly from Houthakker; because Houthakker died three years before the Florence flood, presumably his son Lodewijk was meant. The Bonna drawing is said to have come from the Houthakker Collection to a private collection in New York before it was acquired from Katrin Bellinger Kunsthandel. Possibly Muensterberger owned all three drawings from the group before selling the Bonna and Metropolitan Museum ones to Bellinger and donating the third to the Morgan some years later.

Houthakker, Bernard, 1884-1963, former owner.

Houthakker, Lodewijk, former owner.

Muensterberger, Werner, former owner.

Rhoda Eitel-Porter and and John Marciari, Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 2019, no. 101.

Selected references: New York 2010, 113, under note 9.