Tintoretto was born in Venice in late 1518 or early 1519 and was an independent master by 1538, but his artistic training remains a mystery. He surely studied Titian’s works, and he painted alongside Bonifacio de’ Pitati and Andrea Schiavone and was much influenced by the muscular works of Pordenone (see I, 70), but he may have been largely self-taught. He emerged from the artistic traditions of Venice, but he developed a bold and idiosyncratic style that would come to dominate Venetian art in the later decades of the sixteenth century.

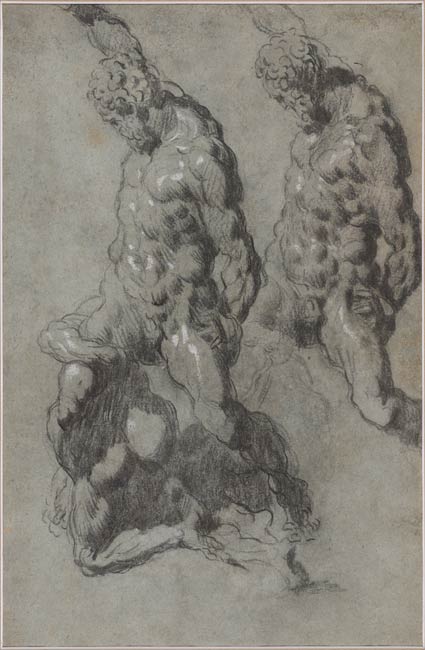

A large body of Tintoretto’s drawings has survived but none from earlier than the mid-1540s, by which time he was already well established. With the exception of a very small number of compositional studies, his extant drawings can be divided into two main categories: individual figure studies that are preparatory for his paintings and sheets like the present work that are drawn after sculptural models. This is one of more than sixty drawings after Michelangelo’s Samson and the Philistines; there are also at least thirty drawings after the ancient bust known as the Grimani Vitellius and around forty after Michelangelo’s Medici tomb figures. There has been a tendency among scholars to date these drawings early in Tintoretto’s career, often to the late 1540s or earliest 1550s, because this study of Michelangelo seemed the work of a young artist striving to find his way and fit the idea of Tintoretto as a self-taught master. There is, however, much to suggest that most of these drawings were in fact made decades later and were not for Tintoretto’s own education but rather for the training of his assistants.1

Raffaello Borghini, for example, noted that Tintoretto continued to collect and study models of famous statues even when the artist was in his sixties. The practice would thus have continued into the 1570s and 1580s, contemporary with Borghini’s writing and at a time when Tintoretto’s work at San Rocco and the Palazzo Ducale required ever more assistance from a workshop.2 In light of this, one can also observe that a large percentage of the surviving drawings are not studied directly from the sculptures themselves but are instead copies of previous drawings, with the attendant loss of detail and flattening of forms. The recto and verso of the present sheet, for example, include multiple views of the sculptural group from a single vantage point. The study at left on the recto is by far the best of the three and could perhaps be by Tintoretto himself. It shows more pentimenti—more redrawn contours, as if made by a draftsman seeking to understand the sculpted form—than are usually found in drawings of this type. In the study at right on the recto, however, the pattern of shadow along Samson’s back and neck has largely ceased to define form and is a flattened, almost abstracted shape—the benchmark of a copy. Finally, the verso is an ever weaker echo, especially if one looks to the complicated area in the lower part of the group: it is not entirely clear that the draftsman understood, or cared to understand, how the feet at the base of the group connected to the legs of the two Philistines, or how the two Philistines were situated beneath Samson. Many of the sculpture drawings are similarly vague about the exact forms being depicted, with shadowed areas of the body often reduced to a flat dark patch of chalk marks. Furthermore, many of the drawings after the Samson have the same mise-en-page on both recto and verso, as if Tintoretto pasted his own study of the sculpture to the wall of the studio beside the sculptural cast and had his students interpret the sculpture by copying the master’s drawing of it.

At a basic level, the drawings after the Samson group document Tintoretto’s interest in Michelangelo’s distinctive way of conveying meaning through the muscular human body. That is what Tintoretto himself learned from Michelangelo’s works in the early part of his career and also what he must have sought to teach to his assistants and pupils. The goal of the drawing exercises was to learn a way of understanding and using the human form rather than to copy Michelangelo per se. For all the interest in Michelangelo’s art, however, the drawings are notably Venetian in style, using black chalk, charcoal, and white chalk on blue paper.

The origins of Michelangelo’s sculpture can be traced to 1527. Leo X had commissioned Michelangelo to make a Hercules and Cacus that would be paired with the David outside the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, but the project stalled after the death of the pope. When the commission was revived in the time of Clement VII, it was instead assigned to Baccio Bandinelli. After the expulsion of the Medici from Florence in 1527, the new republican government returned the commission to Michelangelo, who changed the subject to Samson standing over two vanquished Philistines. He made a model for the new composition, but the siege of Florence and other events prevented him from carving the marble, and when the Medici returned to Florence, the block was given back to Bandinelli, who finished the Hercules and Cacus.3 Small bronze casts, most generally dated to the 1550s or later, were nonetheless made from Michelangelo’s Samson model. It is not known when a cast of the sculpture first arrived in Venice or how Tintoretto obtained his own model, which must have been a clay or wax version as some drawings of the back of the group show a vertical support that would be unnecessary with a bronze.4 The drawings by Tintoretto and his workshop were, interestingly, at the same scale as the sculptural cast: the drawings of the full group are generally about 360–70 millimeters in height, matching the dimensions of the bronze casts that survive.5

—JJM

Footnotes:

- For the present author’s full discussion of the sculpture drawings and of Tintoretto’s draftsmanship in general, see New York and Washington 2018–19.

- Borghini 1967, 1:558.

- Vasari 1878–85, 6:148–51. On the Michelangelo model, see especially Schmidt 1996 but also Pope-Hennessy and Radcliffe 1970, 186–95.

- Nichols 1999, 59, suggests that the man in red at lower right in the Miracle of the Slave (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice) is based on the Samson, but the correspondence is not so close and it is not certain that the copies of the sculptural group circulated widely until the 1550s.

- Some of the drawings, such as that at Harvard, are on taller sheets of paper, but the figure group is drawn at the same scale as the sculpture.

Tintoretto produced drawings after sculpture throughout his career, including studies of heads and entire figures after sculptures by Michelangelo. This is one of a group of drawings probably made after a wax or clay model of a sculptural group representing Samson slaying the Philistines that was commissioned from Michelangelo in 1508 and again in 1528 by the republican rulers of Florence. Michelangelo prepared a model but never executed the sculpture; the marble block was eventually used by Baccio Bandinelli for his Hercules and Cacus, which stands in the Piazza della Signoria. Tintoretto's drawings after Michelangelo are often dated to the younger artist's formative period, the 1540s or 1550s, but the sheets were probably not for Tintoretto's own artistic education, but rather, examples drawn for the training of his workshop assistants.

This sheet includes multiple views of the Samson group from a single vantage point. The study at left on the recto is by far the best of the three and with its redrawn contours seems the work of a draftsman seeking to understand the sculpted form; it could perhaps be by Tintoretto himself. In the study at right on the recto, however, the pattern of shadow along Samson's back and neck has largely ceased to define form and is a flattened, almost abstracted shape--the benchmark of a copy. Finally, the verso is an ever weaker echo: it is not entirely clear that the draftsman, surely one of Tintoretto's assistants rather than the master himself, cared to understand how the feet at the base of the group connected to the legs of the two Philistines. -- Exhibition Label, from "Drawing in Tintoretto's Venice"

Watermark: Fragmentary circle, hard to decipher because paper is rough, with many inclusions.

Tintoretto, 1518-1594, Workshop of.

Wharton, Lord, former owner.

Ward-Jackson, Adrian, former owner.

Thaw, Eugene Victor, former owner.

Thaw, Clare, former owner.

Rhoda Eitel-Porter and and John Marciari, Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 2019, no. 69.

John Marciari, Drawing in Tintoretto's Venice, New York, 2018, figs. 77-78, repr.

Selected references: New York 1994-95, no. 8; London 1996-97, no. 8; New York 2006, no. 17; Munich 2008-9, no. 17; New York and Williamstown 2017-18, no. 382; New York and Washington 2018-19, 103-6, 108, 122, and no. 37.

Thaw Catalogue Raisonné, 2017, no. 382, repr.

Denison, Cara D. et al. The Thaw Collection : Master Drawings and New Acquisitions. New York : Pierpont Morgan Library, 1994, no. 8.

From Leonardo to Pollock: Master drawings from the Morgan Library. New York: Morgan Library, 2006, cat. no. 17, p. 40-41.

100 Master drawings from the Morgan Library & Museum. München : Hirmer, 2008, no. 17, repr. [Rhoda Eitel-Porter]