Around 1504–5, Raphael produced for the Franciscan convent of Sant’Antonio da Padova in Perugia the work now known as the Colonna Altarpiece, so called after its seventeenth-century owners.1 He must still have been living in Perugia when he received the commission, but scholars have long held that the painting was produced over an extended period, for there are aspects of the work—the weighty male saints of the central panel (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), for example—which unquestionably reflect Raphael’s study in Florence of the works of Leonardo da Vinci and Fra Bartolommeo, although the general conception of the altarpiece and many of the figures in it reflect the Umbrian traditions of Perugino and others.2 Some of the more traditional and outdated aspects of the work have been, since Vasari, attributed to the agency of the nuns who commissioned it, but it is equally likely that Raphael, in this key transitional moment of his career, was merely reflecting the paintings that seized his imagination: those of Perugino and Signorelli when the project began, and those of the Florentines as he continued working on the altarpiece.3

The now-dispersed predella of the altarpiece included three scenes: the Agony in the Garden (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), the Procession to Calvary (National Gallery, London), and the Pietà (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). Also typical of Raphael around 1504, the Agony in the Garden and Pietà are based on models by Raphael’s master, Perugino, although on works that Raphael would have newly encountered in Florence (formerly in the convent of San Giusto degli Ingesuati, they are now in the Uffizi).4 When designing these scenes, moreover, Raphael employed the traditional method also used by Perugino and made cartoons for each that were then punched and pounced to transfer the design to the panel before the underdrawing was reworked. Infrared reflectography has revealed the pouncing beneath the Procession to Calvary and Pietà. This can be compared to the punched and pounced cartoons for contemporary works such as the Oddi Altarpiece5 or to the cartoon in the British Museum for the Vision of a Knight allegory in the National Gallery, London.6

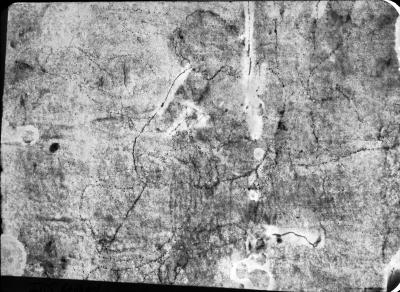

The only scene of the Colonna Altarpiece predella for which a cartoon survives is the Agony in the Garden—the present drawing, pricked for transfer— but, surprisingly, that is the only panel from the predella that does not have evidence of pouncing in its underdrawing. At the time of the London exhibition of 2004–5, however, a new infrared reflectogram was taken of the Gardner Museum’s Pietà, and it was discovered that a cartoon transfer of the Agony in the Garden lay beneath it.7 It seems that the design was transferred to one end of the long horizontal plank on which the predella was to be painted, but then, for unknown reasons (perhaps having to do with the long gestational period of the altarpiece), that panel was flipped. At this stage, Raphael may have freely redrawn the Agony in the Garden, just as he seems to have reworked by hand the central scene of the Procession to Calvary. The matter is further complicated by the main difference between the Morgan drawing and the painting, which is that in the drawing, the chalice symbolizing Christ’s sacrifice sits directly atop the rock at upper right, whereas in the painting, a flying angel brings the cup to Christ. Moreover, x-radiographs have revealed that the predella was originally painted to match the drawing but that the angel was later added over the top; it is presumed that this change brought the work more in accordance with local tradition.8

Considering the absence of pouncing in the underdrawing, the addition of the angel, and the perceived misunderstandings of the design, Plazzotta concluded that the Agony painting must have been executed by an Umbrian associate of Raphael, although this idea has not been accepted by other recent scholars.9 Plazzotta also claimed that the Morgan drawing is not Raphael’s original design, pricked for transfer, but rather an auxiliary cartoon pricked through from another sheet and then reworked by another hand, partly because she believed that there are several pricked lines that lack visible corresponding pen lines or washes beneath. Margaret Holben Ellis subsequently examined the drawing in the Morgan’s Thaw Conservation Center in 2008, but she concluded that this does not seem to be the case and that the “missing” lines are a question of the drawing’s damaged condition. This lends support to the argument that the drawing is Raphael’s original design, as has otherwise always been believed.

—JJM

Footnotes:

- On the Colonna Altarpiece, see especially New York 2006a, although the important contributions of London 2004–5 and Plazzotta 2006 must also be considered.

- Oberhuber 1977 and Penny 1996, 25:898, argue that the work may have been started as early as 1501, although virtually all recent scholars have instead placed the origins in 1504, not long before Raphael’s move to Florence. It is also unclear when the work was complete. Waagen 1838, 3:141, claimed that the date of 1505 was inscribed on the altarpiece, which would have indicated a date of completion, but there is no other reference to this supposed inscription.

- Vasari 1878–85, 4:324, claimed, for example, that the clothed Christ child (otherwise absent from Raphael’s work but found in Pinturicchio’s) was a concession to the nuns.

- As observed by Plazzotta in London 2004–5, 150.

- For a recent discussion of the drawings, see New York 2017, no. 23; for technical study of the panels, see also London 2002, no. 8.

- See London 2004–5, nos. 35–36; the British Museum drawing is inv. 1994,514.57.

- Plazzotta 2006, 709.

- Washington 1983, 121. Other Umbrian examples of the iconography are in Nucciarelli 1998, 264–79.

- Plazzotta 2006, 709.

Small cartoon for one of the predella paintings of Raphael's "Pala Colonna", now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York; J. P. Morgan once owned the alterpiece, but not the predella.

Inscribed on verso, at lower center, in pen and brown ink, "Timoteo Viti".

Watermark: Eagle displayed (akin to Briquet 86: Pistoia, 1495; the same watermark is found on 1996.9). Note extensive pricking marks visible in beta radiograph.

Viti, Timoteo, 1469-1523, former owner.

Viti-Antaldi, former owner.

Leighton of Stretton, Frederic Leighton, Baron, 1830-1896, former owner.

Murray, Charles Fairfax, 1849-1919, former owner.

Morgan, J. Pierpont (John Pierpont), 1837-1913, former owner.

Morgan, J. P. (John Pierpont), 1867-1943, former owner.

Rhoda Eitel-Porter and and John Marciari, Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 2019, no. 29.

Selected references: Fairfax Murray 1905-12, 1:15; Schubring 1923, 3-5; New York 1965-66, no. 48; Joannides 1983, 152; Knab, Mitsch, and Oberhuber 1983, no. 24; Meyer zur Capellen 2001, 176-78; London 2002-3, 122-27; London 2004-5, 155n2; New York 2006a, 21-22 and no. 17; Plazzotta 2006, 709; Munich 2008-9, no. 10; New York 2017, 239n6.

Collection J. Pierpont Morgan : Drawings by the Old Masters Formed by C. Fairfax Murray. London : Privately printed, 1905-1912, I, 15, repr.

Stampfle, Felice, and Jacob Bean. Drawings from New York collections. I: The Italian Renaissance. New York : Metropolitan Museum of Art : Pierpont Morgan Library, 1965, no. 48.

100 Master drawings from the Morgan Library & Museum. München : Hirmer, 2008, no. 10, repr. [Rhoda Eitel-Porter]