In the fall of 1931, Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) used these pages to work on a draft of what would eventually become the essay “A Letter to a Young Poet.” The essay was published first in The Yale Review, and soon after in the Hogarth Press’s “Letters” series, which consisted of essays written in epistolary form on various topics. Other entries in the series included “A Letter to Madan Blanchard” by E. M. Forster, “A Letter from a Black Sheep” by Francis Birrell, and “A Letter to Adolf Hitler” by Louis Golding.

Woolf was addressing a real “young poet,” John Lehmann (1907–1987), who was then working as an apprentice at the Hogarth Press, the publishing house founded by Woolf and her husband, Leonard. Lehmann had greatly admired The Waves, which Woolf completed at the end of June 1931 and which was published by the press on October 8th. Lehmann’s first book of poetry, A Garden Revisited, had also just been published by the Woolfs. Lehmann suggested the idea of the essay to Woolf in a letter praising The Waves, saying that it was “high time for her to define her views about modern poetry.” Woolf had been thinking about different literary forms in the course of writing The Waves, which she sometimes described as a “playpoem,” and she turned to this next project quickly, beginning the draft a week after she responded to Lehmann.

There are two other literary manuscripts in the notebook, a monologue in the voice of a cook (pp. 46-48) and a letter to the newspapers lamenting the suburbanization of the English countryside (pp. 3-5). Like the draft of “A Letter to a Young Poet,” they show Woolf in the midst of the continual trying-out that writing involves—trying out words, phrases, attitudes, personae, lines of argument. The alternate possibilities that writers in the digital era tend to delete from a document in the process of composing are preserved here. Woolf did not complete or publish either of these pieces, though they do have connections to other writing she was doing in this period and afterwards.

This set of sheets, pierced with four holes down the left side through which white thread has been drawn and tied, may have been bound by Woolf herself. Woolf took bookbinding classes from the binder Sylvia Stebbing in 1901 and worked on bookbinding projects—some limited, some more involved, all a chance to experiment with materials, colors, and styles—throughout her life. A number of the early publications of the Hogarth Press were sewn and bound by Woolf. She also added the vertical blue line that can be seen on these pages, creating a wide left-hand margin. This practice of hers dates back to the early 1920s and appears in her notebooks, manuscripts, and diaries.

Introduction by Sal Robinson, Assistant Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, 2019. This text draws on the research and publications of Julia Briggs, Mark Hussey, Alan Isaac, Clara Jones, Emily Kopley, and Barbara Lounsberry.

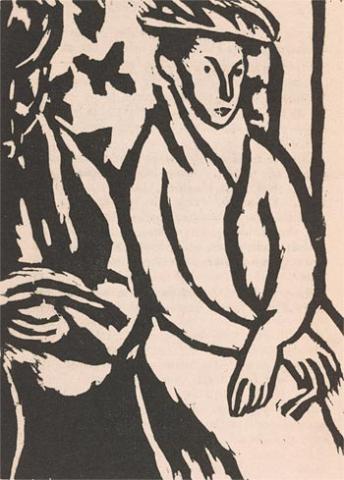

Vanessa Bell (1879-1961)

From Monday or Tuesday by Virginia Woolf (Richmond: The Hogarth Press, 1921)

Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. PML 136392. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2013. © Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett.