Book of Hours, in Latin and French

Illuminated by the Master of the Bible of Jean de Sy

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

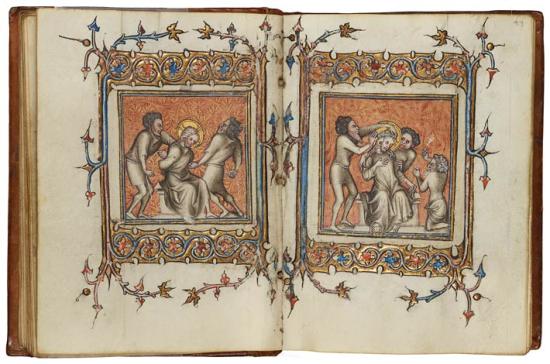

It was an unwritten rule for medieval artists that Christ was never fashionable. The opposite, however, applied to torturers and executioners, whose foppish obsession with elegant clothing was a reflection of their depravity. The two tormentors at the left wear the cote hardy with a loose bodice and a knee-length skirt. At the right, the kneeling man, who mockingly offers the Savior a reed as a scepter, also wears the cote hardy, the skirt of which is tucked into his belt. The bearded man, who rams the Crown of Thorns onto Christ's head, wears the shorter and tighter doublet.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).