Worksop Bestiary

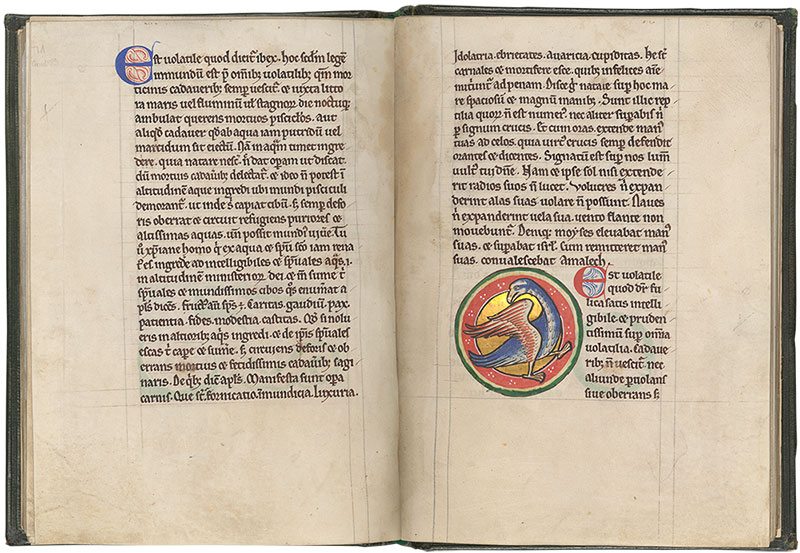

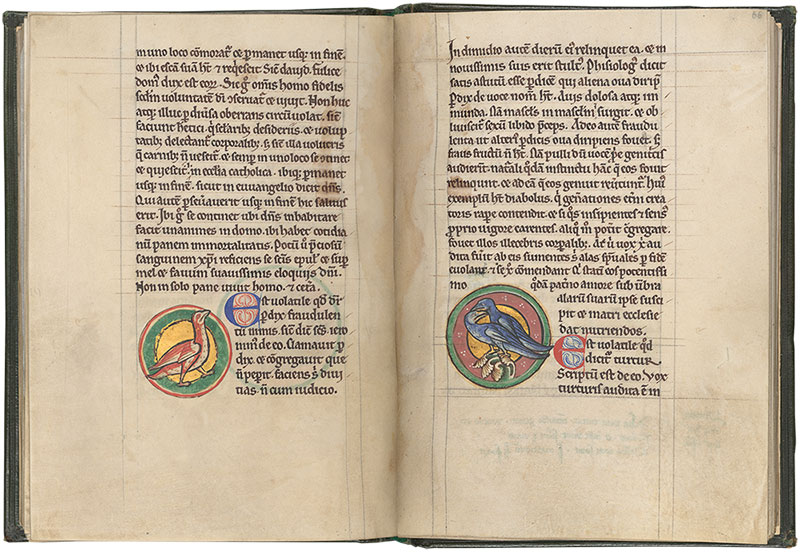

The wondrous creatures of the bestiary inspired delight and fascination by mixing the familiar with the strange, the local with the distant, and the dangerous with the desirable. The animals are presented in the manner of an encyclopedia. Generally, each entry provides a physical description of the creature, followed by notes on its location, habitat, behaviors, and its allegorical significance. Bestiaries were meant to reveal to medieval Christians the wonder of creation and the hidden meanings they believed were built by God into the natural world.

Saw-fish

Worksop Bestiary

England, possibly in Lincoln or York, ca. 1185

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fol. 69r (detail)

Thumbnails

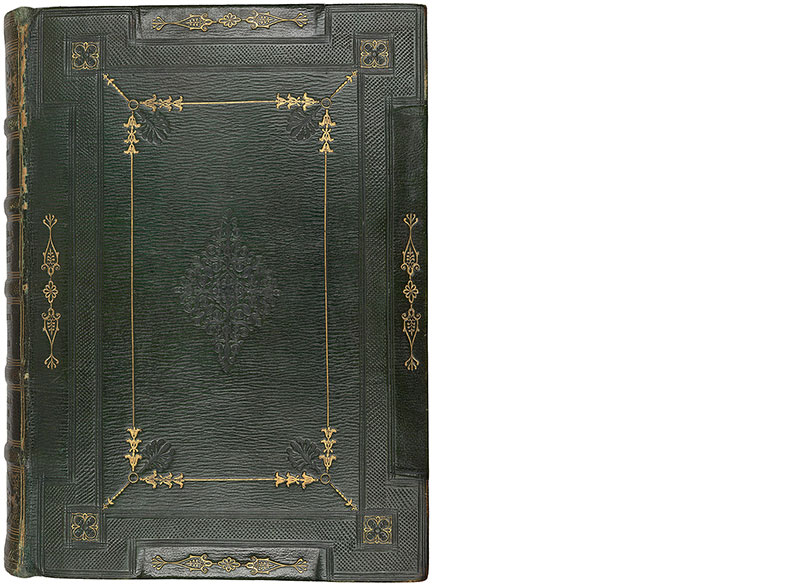

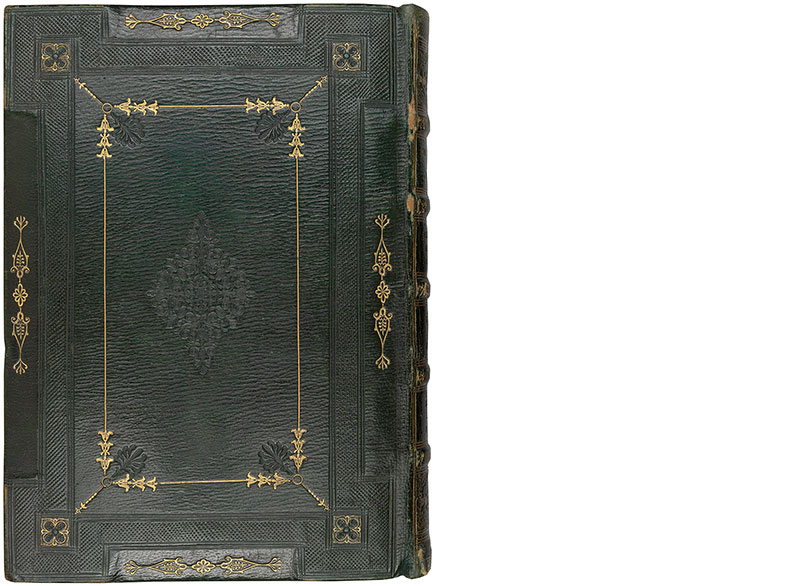

MS M.81, front cover

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

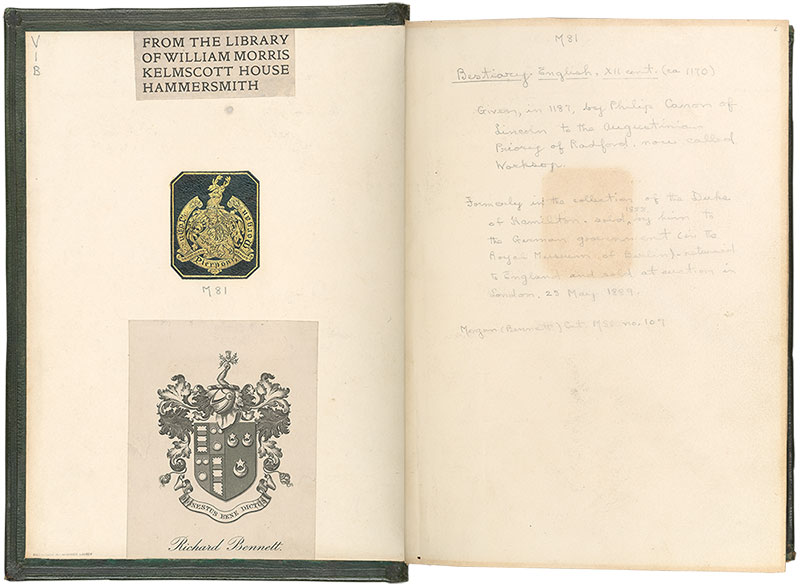

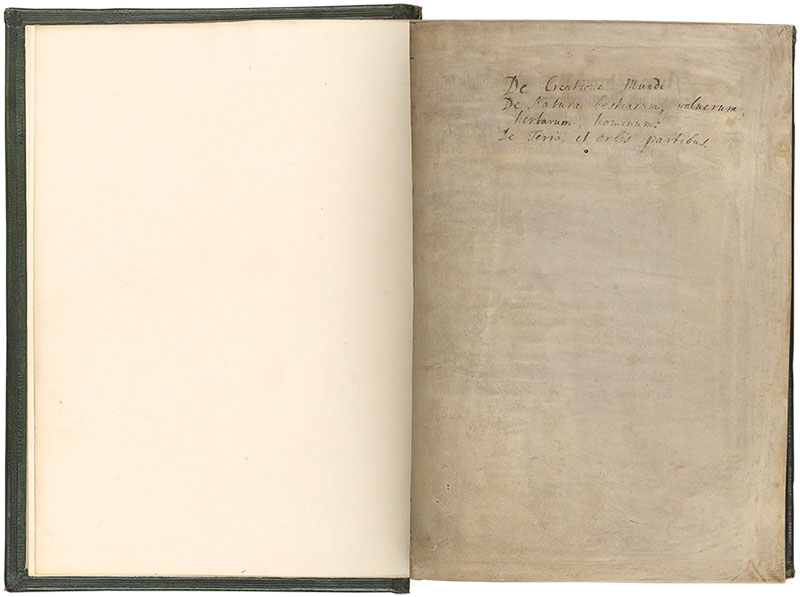

MS M.81, inside front cover–fol. [i]r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

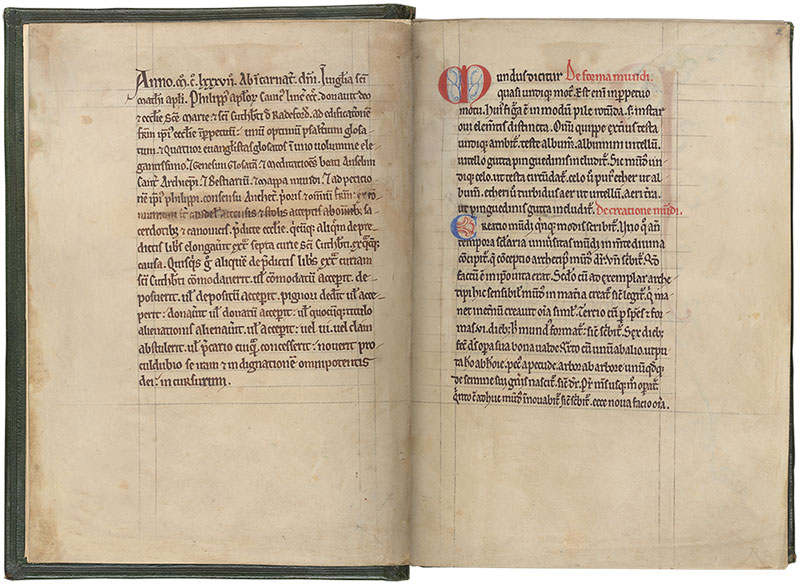

MS M.81, fols. [i]v–[iii]r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

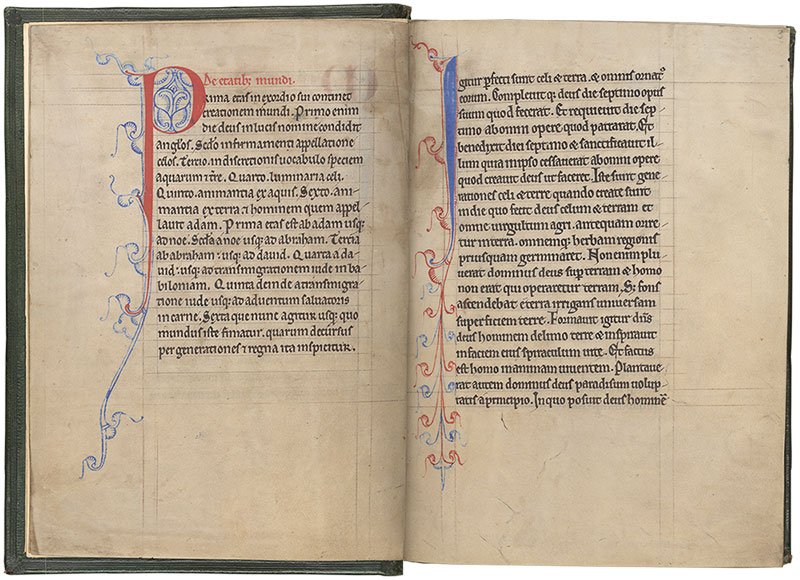

MS M.81, fols. [ii]v–[iii]r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

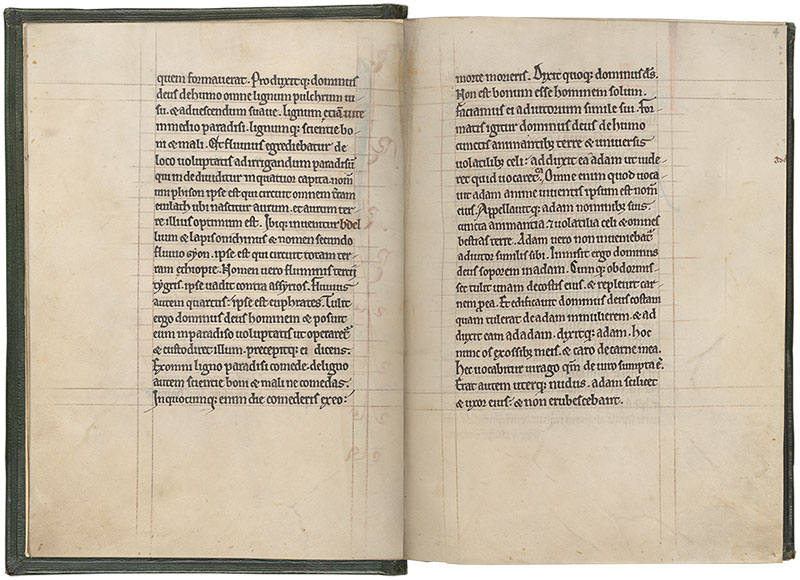

MS M.81, fols. [iii]v–1r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

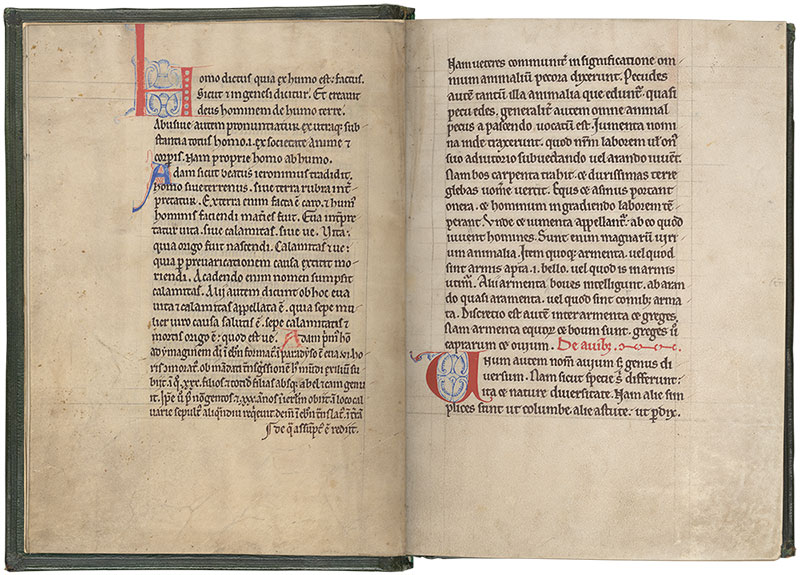

MS M.81, fols. 1v–2r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 2v–3r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 3v–4r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 4v–5r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

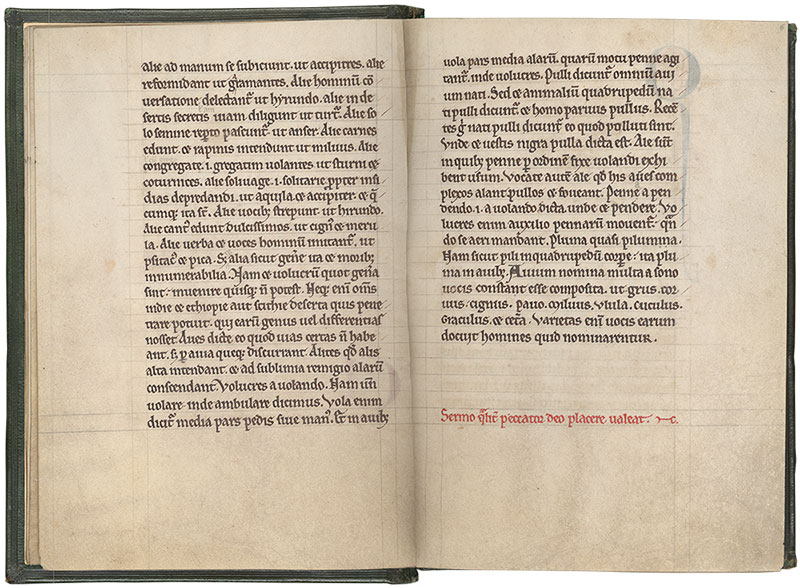

MS M.81, fols. 5v–6r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 6v–7r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

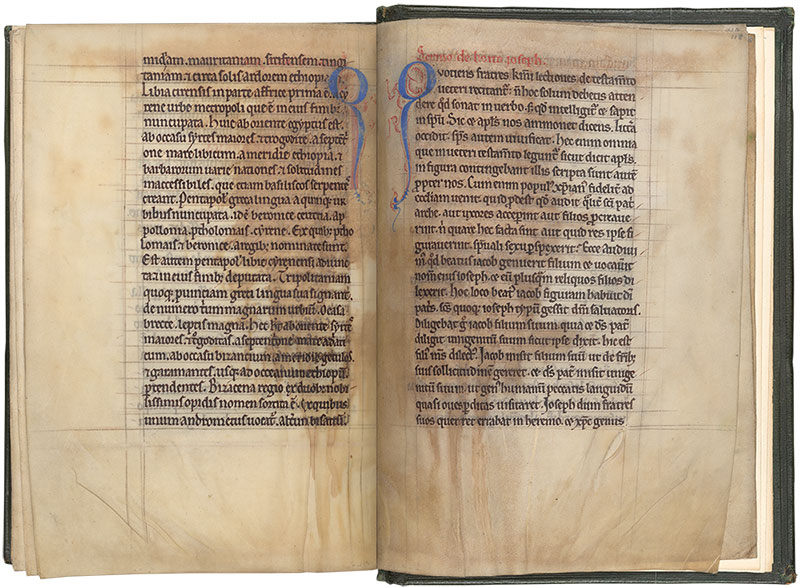

MS M.81, fols. 7v–8r

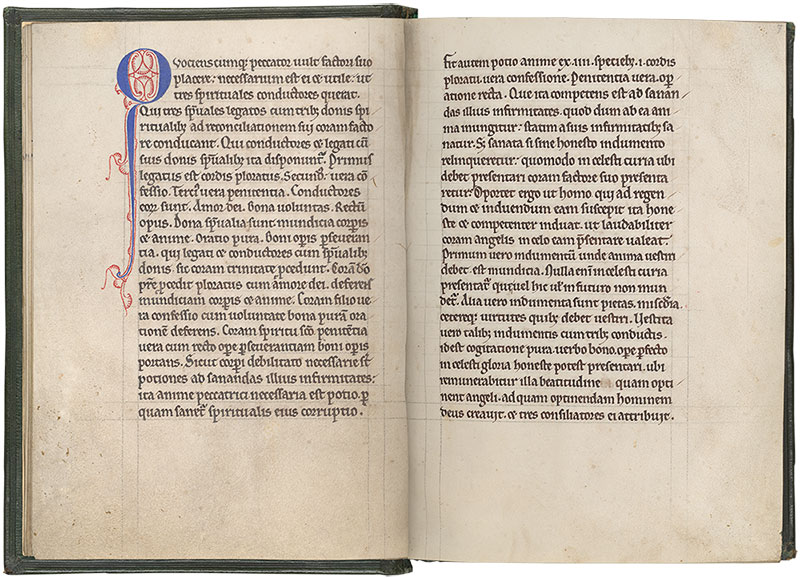

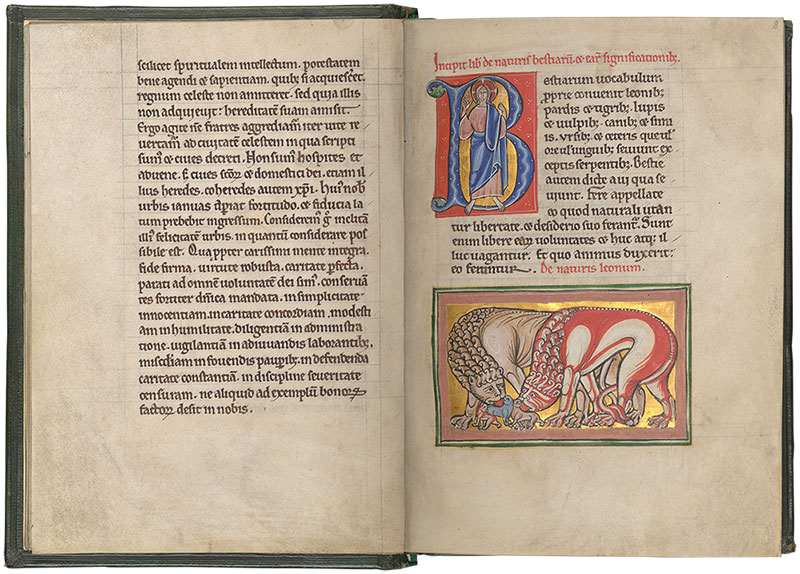

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

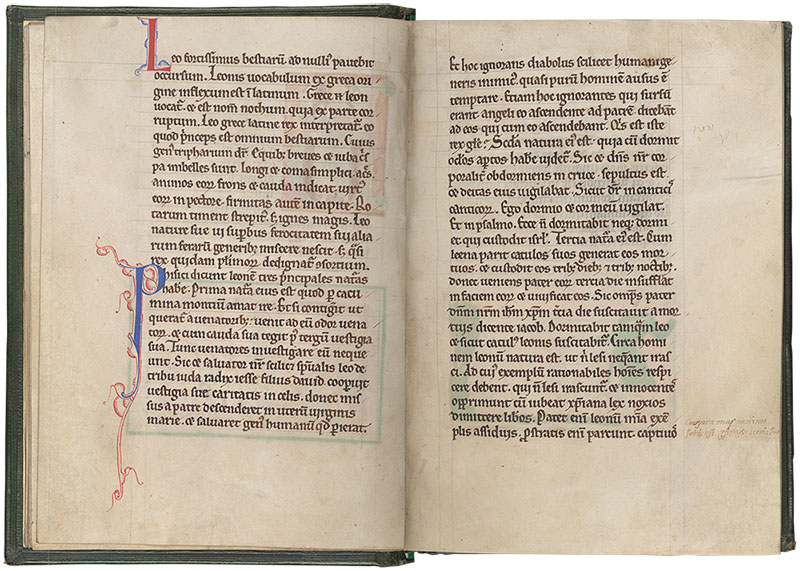

Lions

A figure of Christ in the initial “B” opens the bestiary and emphasizes the allegorical link to the lions, shown below, licking their stillborn cubs back to life.

MS M.81, fols. 8v–9r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 9v–10r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

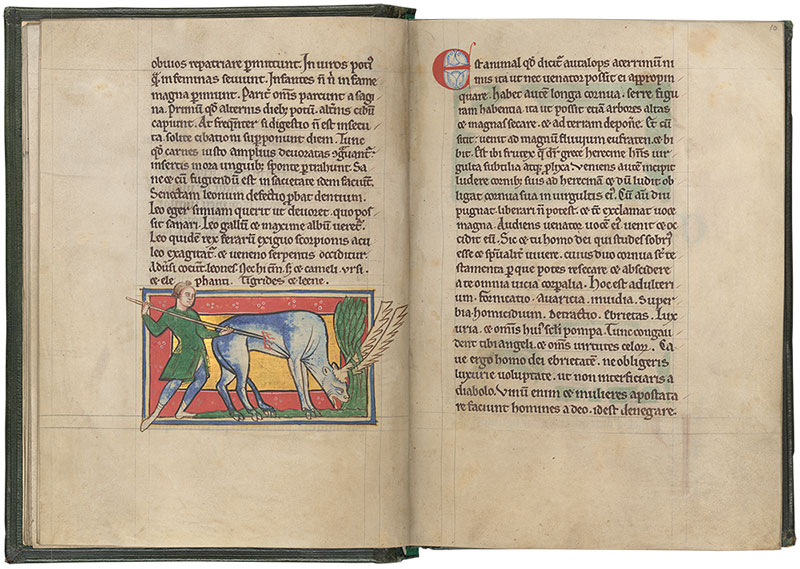

Antelope

A hunter takes advantage of an antelope that has trapped itself with its tangled antlers—symbols of vice and temptation.

MS M.81, fols. 10v–11r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

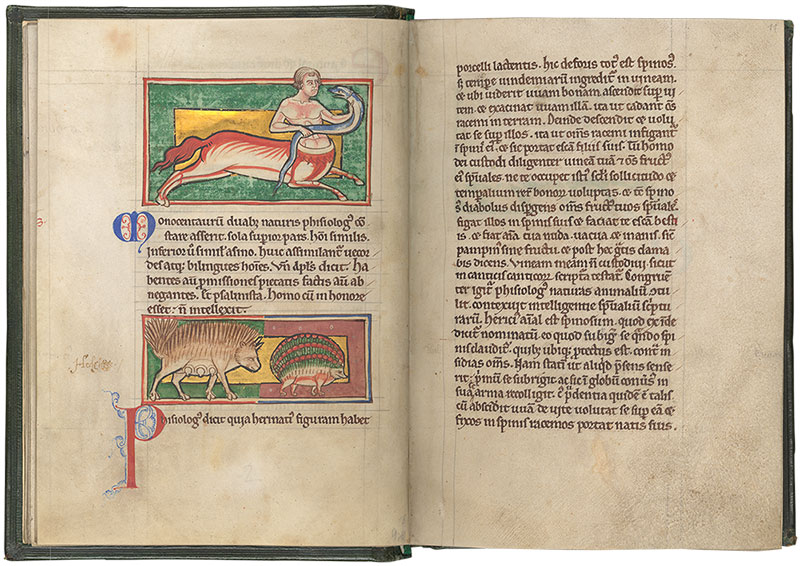

Centaur and Hedgehogs

A monocentaur (human/donkey hybrid) wrestles a snake. Below, two hedgehogs head home to feed their young with grapes speared on the smaller one’s spines.

MS M.81, fols. 11v–12r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

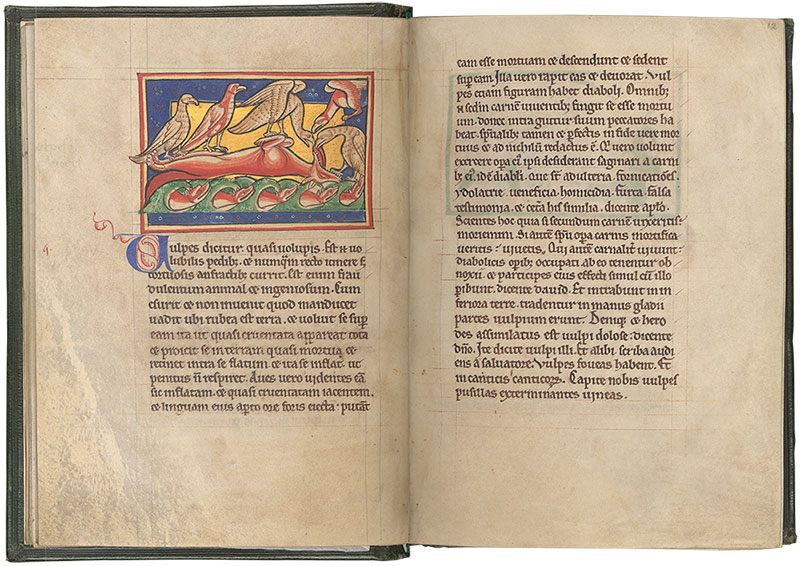

Fox

A fox plays dead to lure vultures into its grasp; below, its offspring eagerly await their dinner.

MS M.81, fols. 12v–13r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

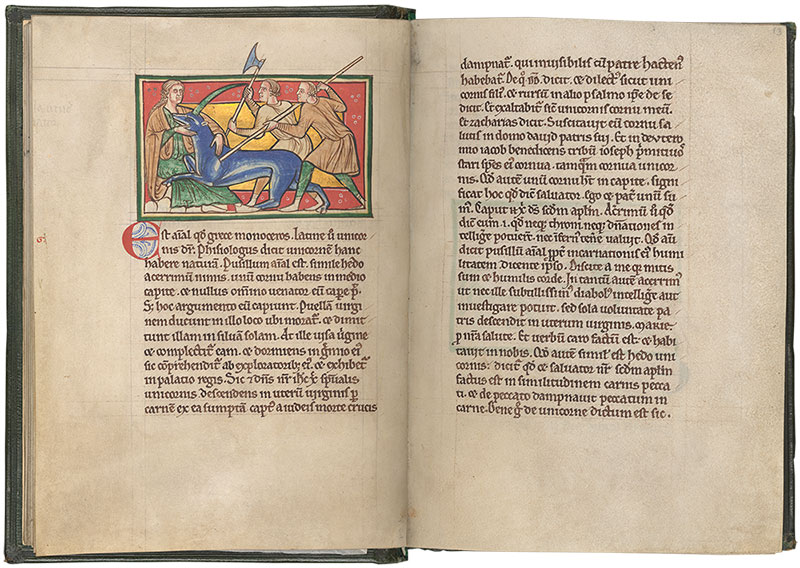

Unicorn

Two hunters kill a unicorn that has been lured into the lap of a virgin.

MS M.81, fols. 13v–14r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

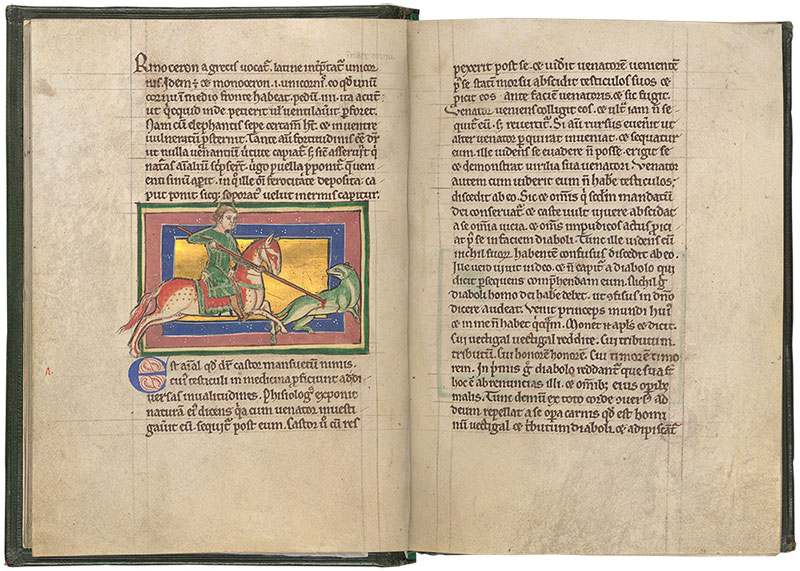

Beaver

A hunter kills a beaver for its testicles, which were thought to have medicinal value.

MS M.81, fols. 14v–15r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

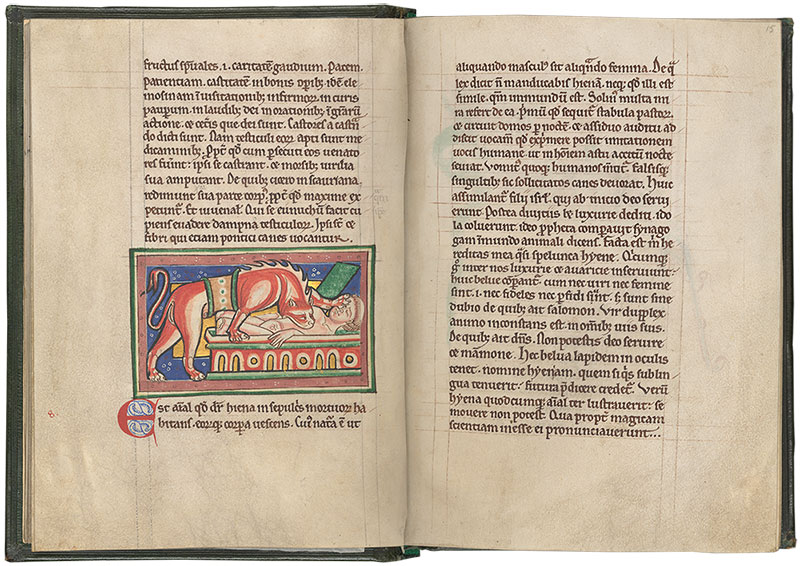

Hyena

A hyena demonstrates why it was thought to be an unclean animal by feasting on a corpse; the anti-Jewish text associates it with “the children of Israel.”

MS M.81, fols. 15v–16r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

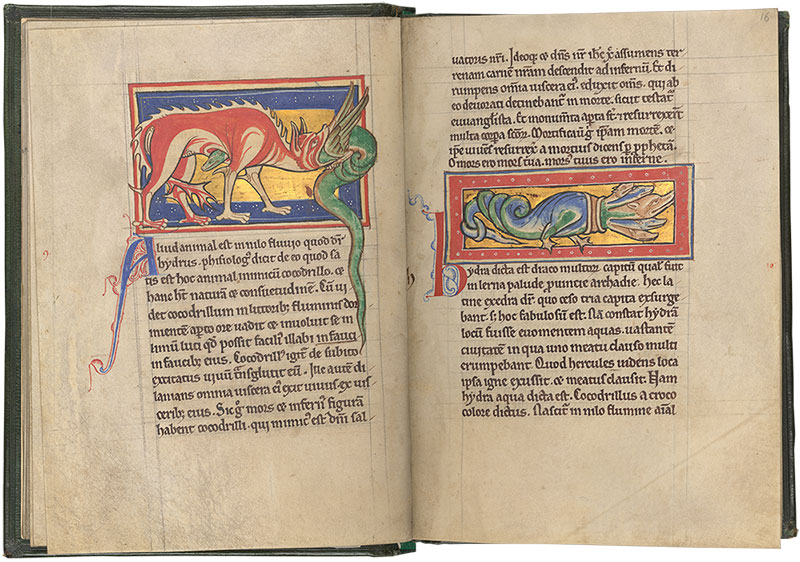

Hydrus (left)

A hydrus (winged snake) is being swallowed alive by a fantastic crocodile, only to break out from the belly of the beast unharmed.

Hydra (right)

The hydra—a snake with regenerating heads associated with Hercules—is one animal the bestiary text tells us is not real.

MS M.81, fols. 16v–17r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

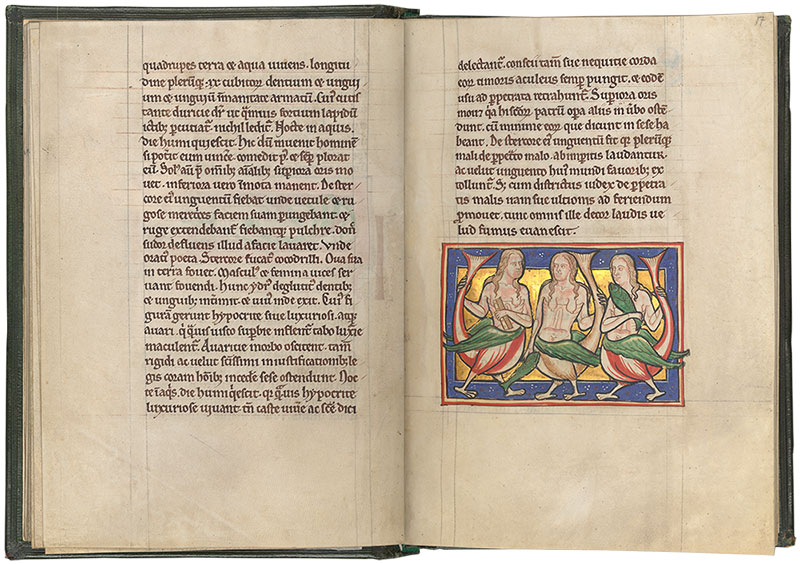

Sirens

These sirens—part bird, part fish, part woman—personify lust, and were thought to lure sailors to their death with their beautiful songs.

MS M.81, fols. 17v–18r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

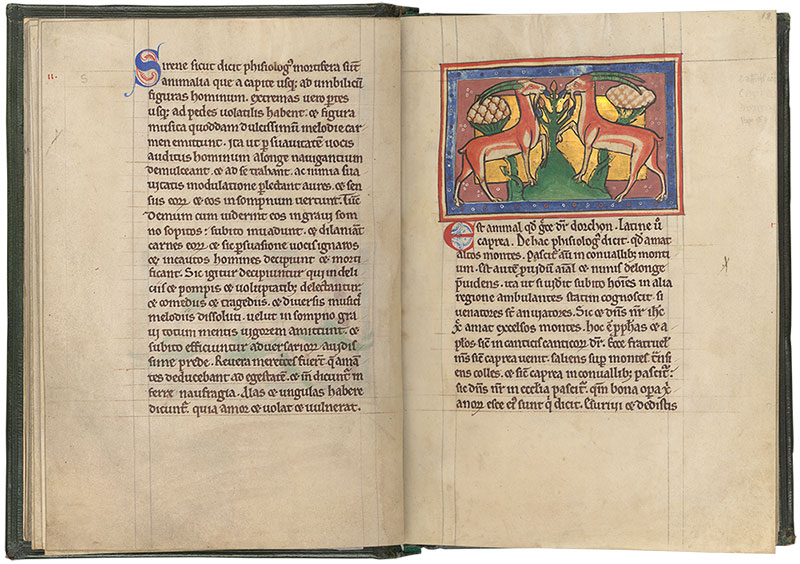

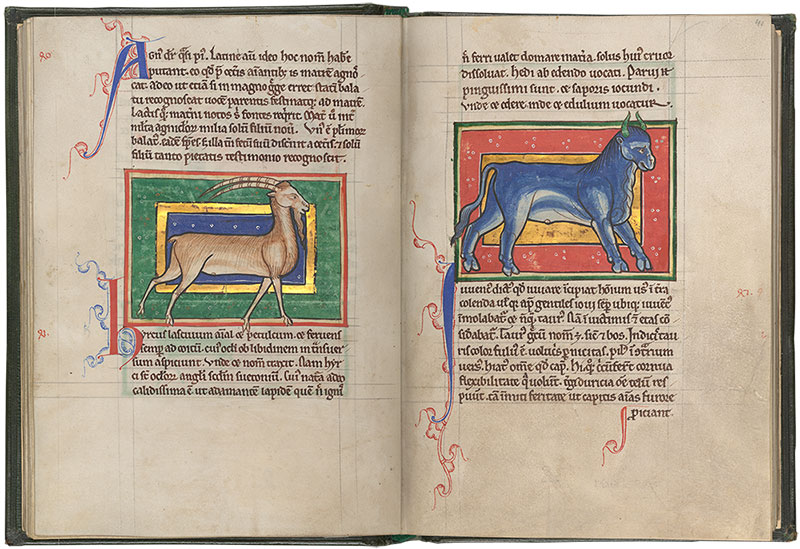

Goats

Wild goats possess sharp eyesight, love high mountains, and feed in valleys. The text interprets them with the help of the Song of Songs, a pastoral love poem included in both the Hebrew and Christian Bible. It directly compares the goat’s characteristics with Christ’s majesty.

MS M.81, fols. 18v–19r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

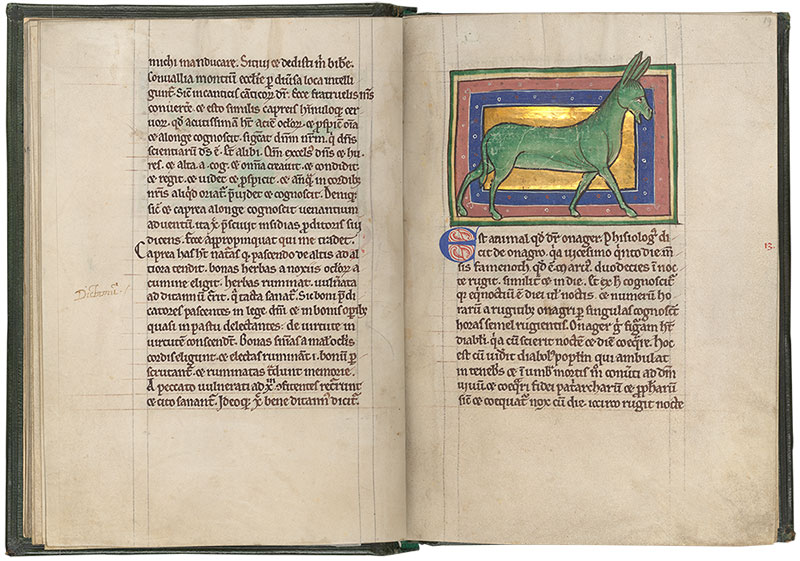

Onager

This unnaturally green onager (wild ass) was thought to mark each hour by braying, prompting a comparison to the devil, “who knows how to make day and night the same.”

MS M.81, fols. 19v–20r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

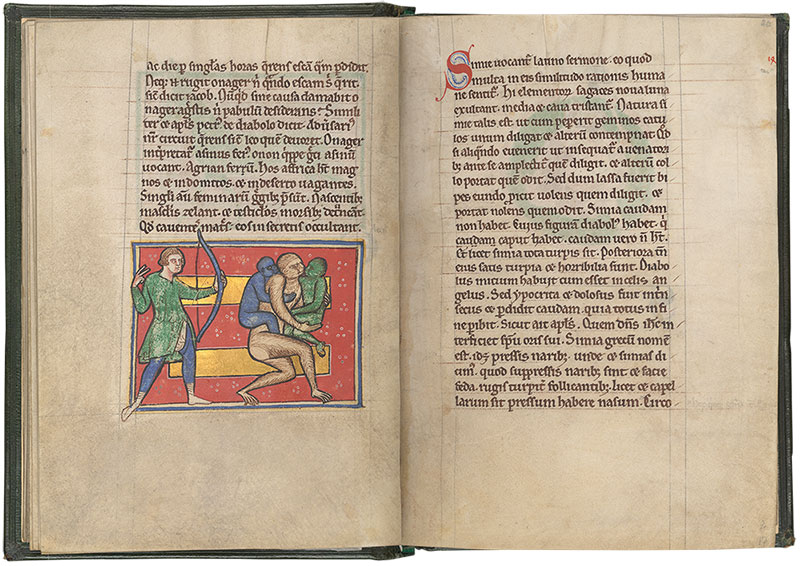

Apes

Here, the illuminator depicts a scene from the text: when an ape has twins, it loves one and hates the other. If hunted, the mother holds the beloved infant in her arms and carries the hated one on her back. When she is too tired to run upright, she drops the beloved child while the hated offspring clings to her back.

MS M.81, fols. 20v–21r

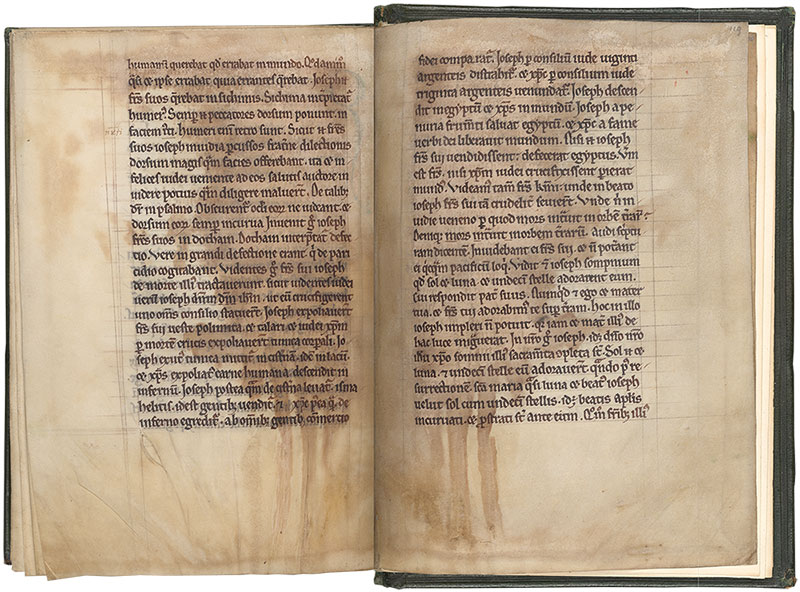

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

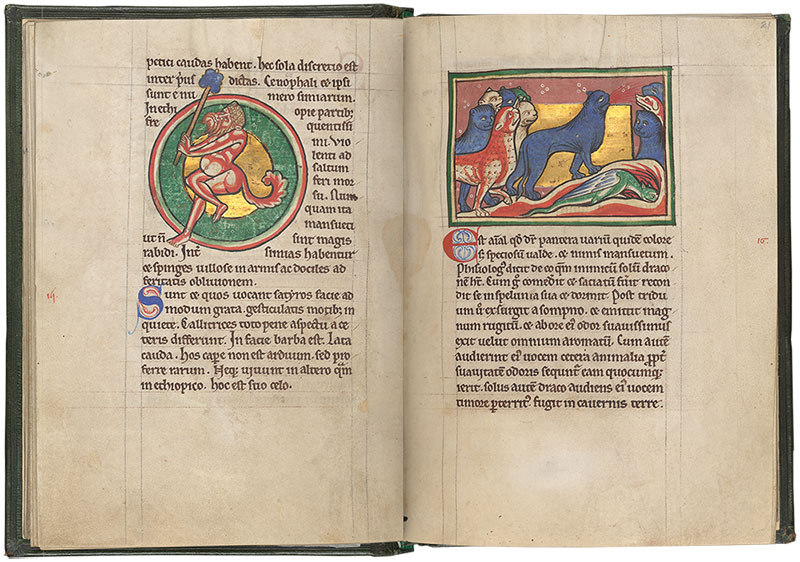

Satyr (left)

This Satyr—associated with the Greek god Dionysus by its pine-cone topped thyrsus—is classified in the bestiary as a type of ape.

Panther (right)

Here the panther invites a comparison to Christ by emitting a sweet-smelling roar following a three-day slumber. In response, a demonic dragon buries itself in “the caverns of the earth.”

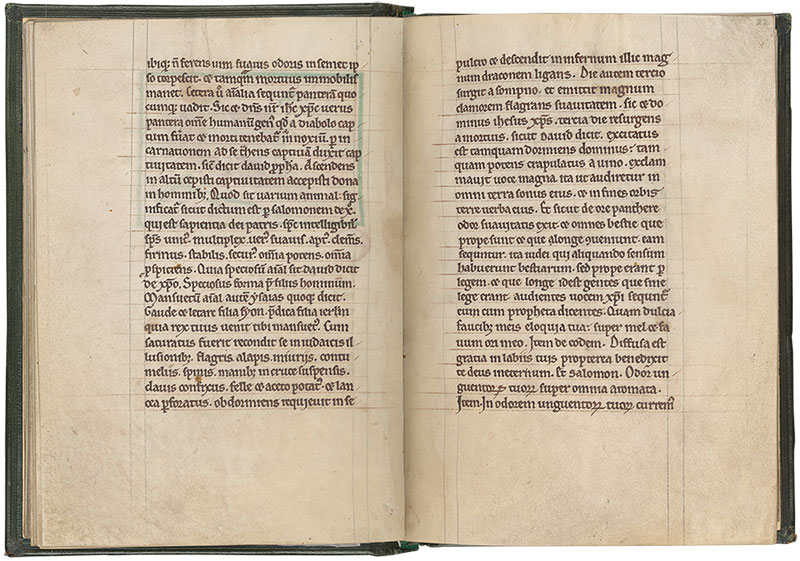

MS M.81, fols. 21v–22r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 22v–23r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

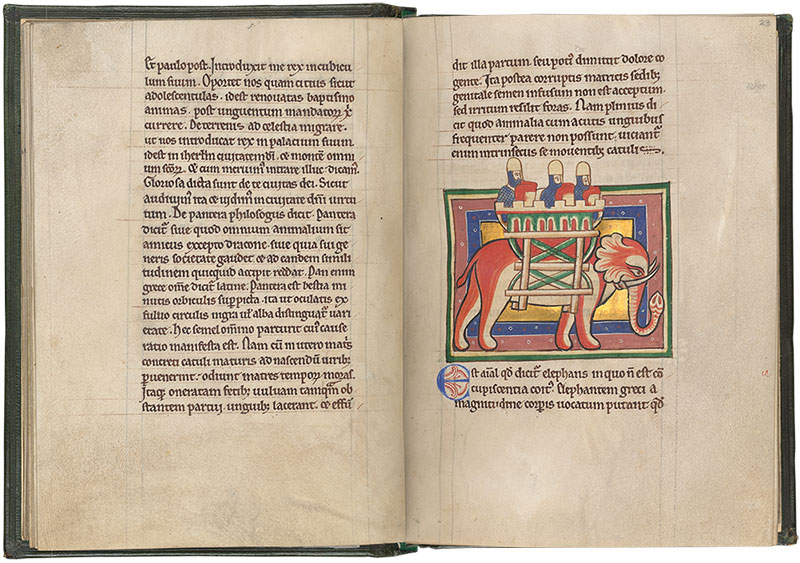

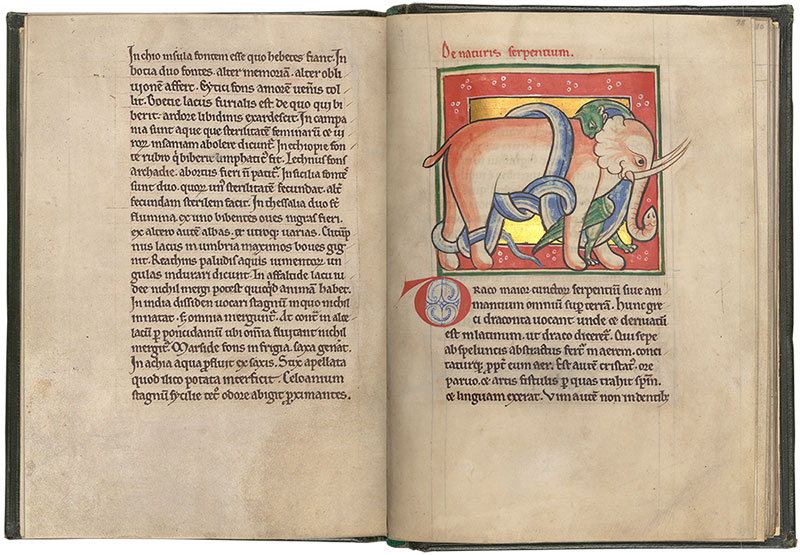

Elephant

This folio illustrates the bestiary’s account of how Persians and Indians used howdahs, or wooden towers, on battle elephants.

MS M.81, fols. 23v–24r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 24v–25r

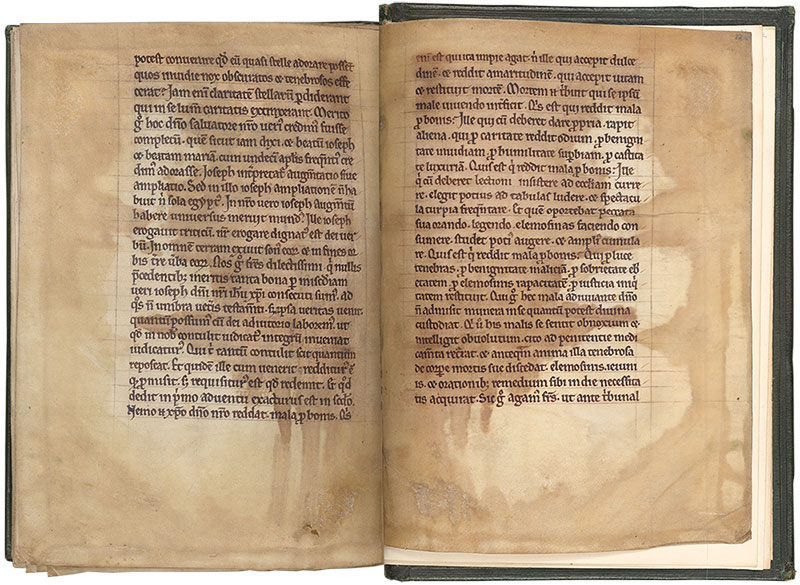

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 25v–26r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

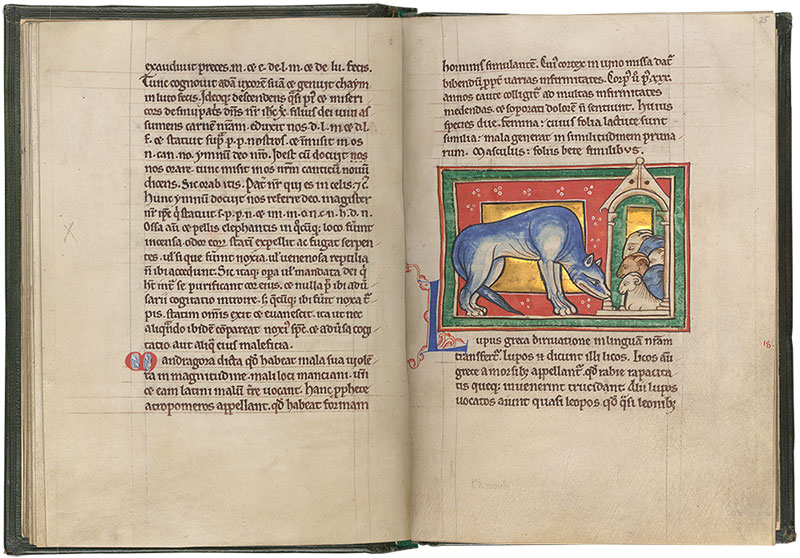

Wolf

Described allegorically as the devil, a wolf is shown here stalking the faithful sheep who find sanctuary in a church-like sheepfold.

MS M.81, fols. 26v–27r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

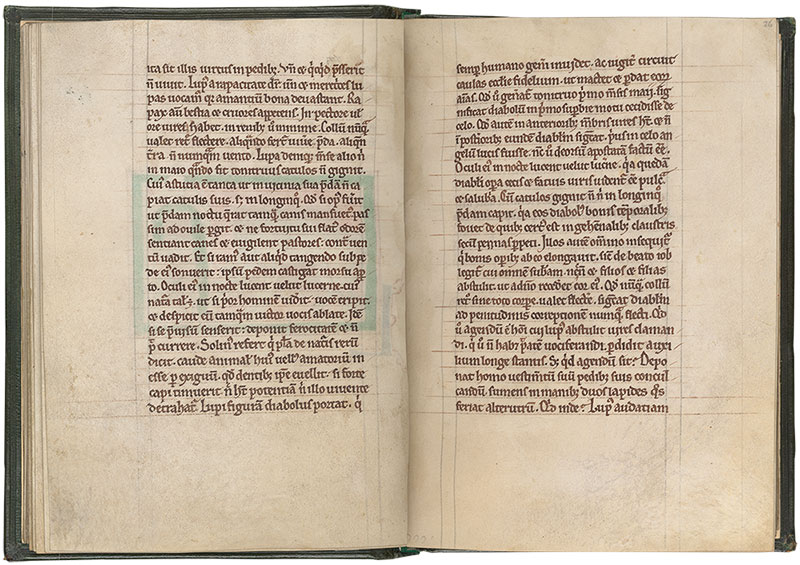

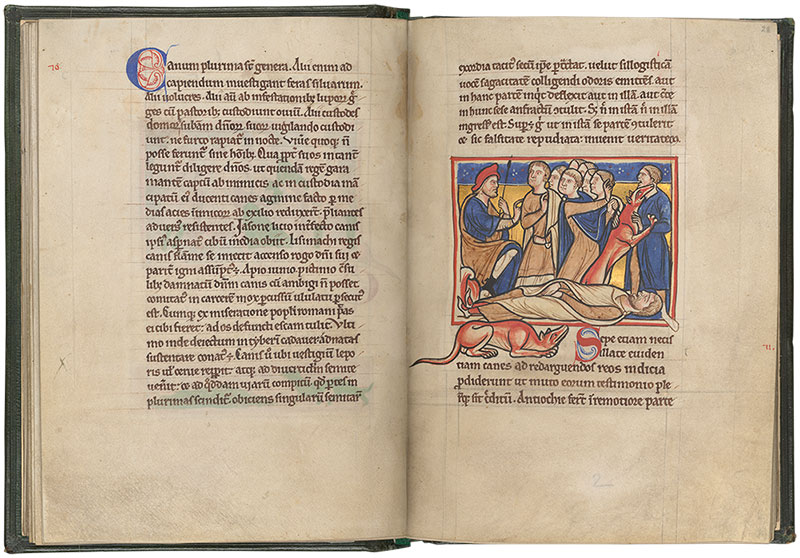

Dogs

The loyal dogs of King Garamantes rescue him from his enemies.

MS M.81, fols. 27v–28r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

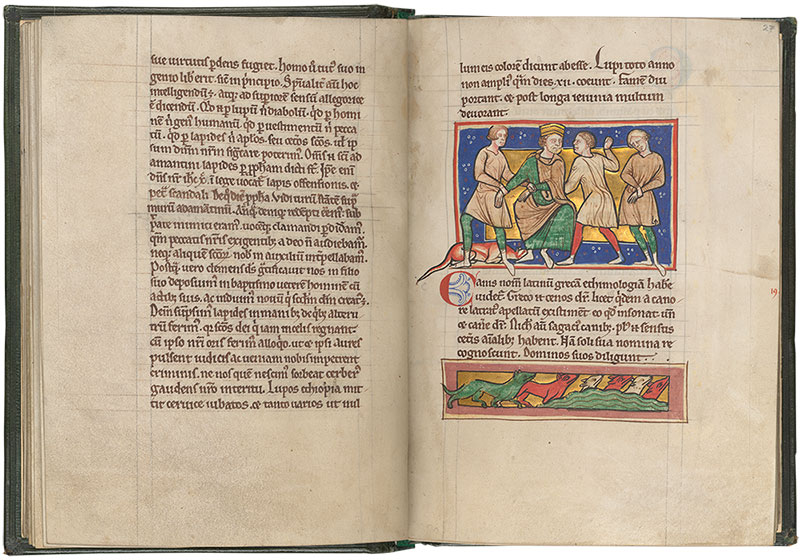

Dog

A faithful dog identifies a murderer, demonstrating that while sinners may be able to hide their deeds from other humans, God and his creatures will know the truth.

MS M.81, fols. 28v–29r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 29v–30r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

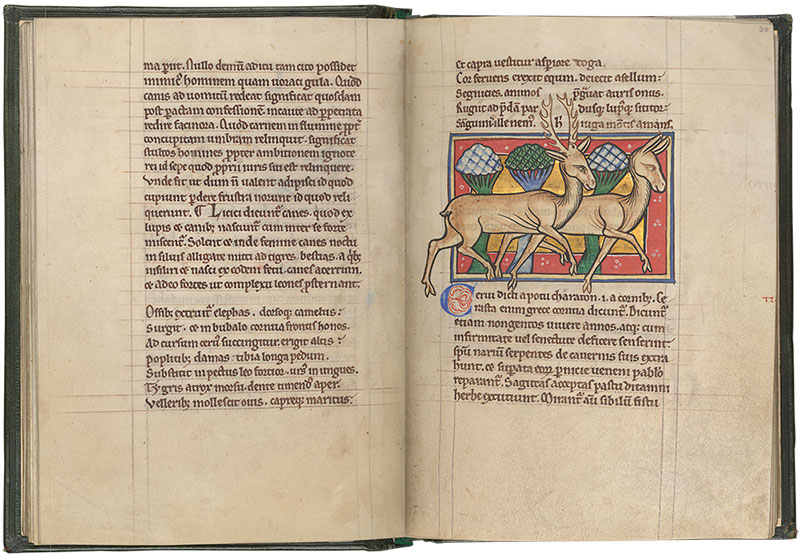

Deer

Deer in bestiaries were associated with Christ, especially when shown trampling a snake (symbol of Satan), or running to “Christ, the true spring.” But here, a stag and doe walk side by side in front of three trees, without these points of reference.

MS M.81, fols. 30v–31r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

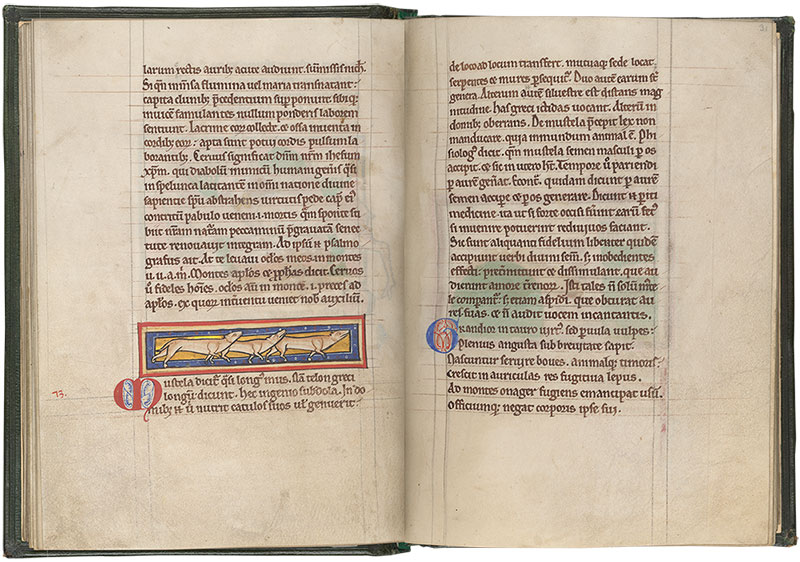

Weasels

The weasels walking with their noses pointed upwards may be seeking their lost offspring, which we are told they are able to revive from the dead, but only if they find them.

MS M.81, fols. 31v–32r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

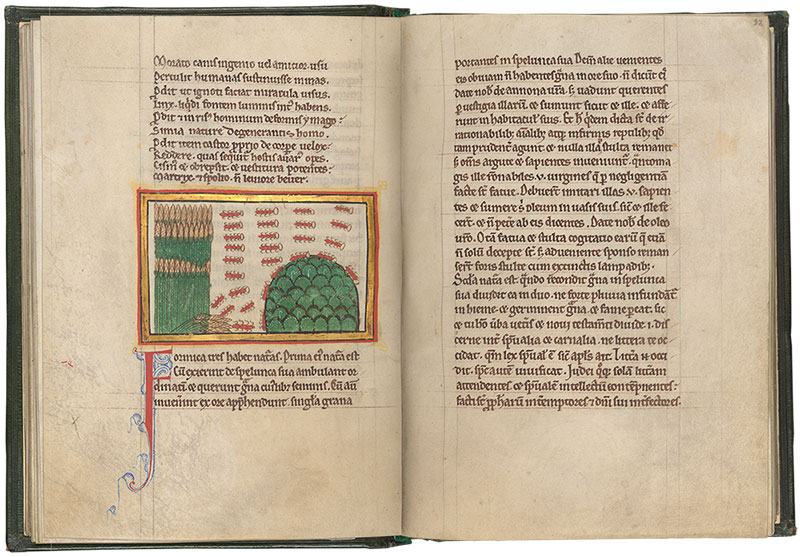

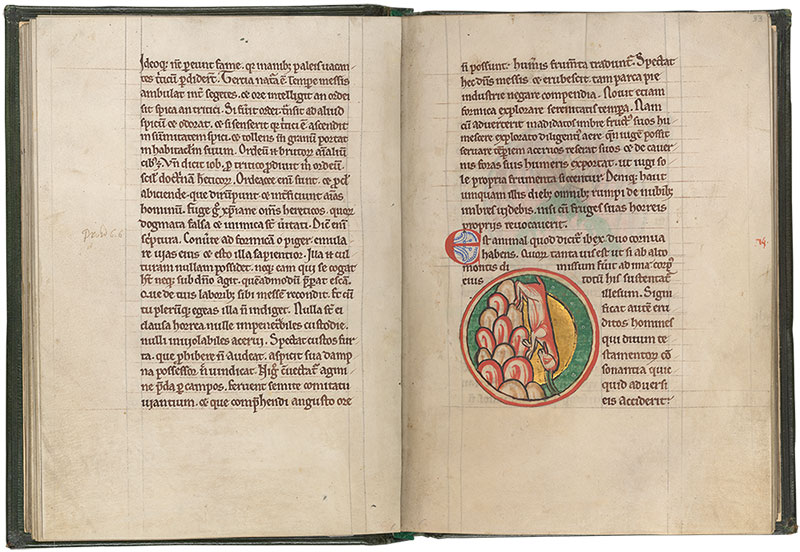

Ants

Ants work together to harvest wheat for the colony—a model of dutiful behavior for Christians.

MS M.81, fols. 32v–33r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Ibex

An ibex plunges headfirst down a mountainside, knowing its horns are strong enough to save it.

MS M.81, fols. 33v–24r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

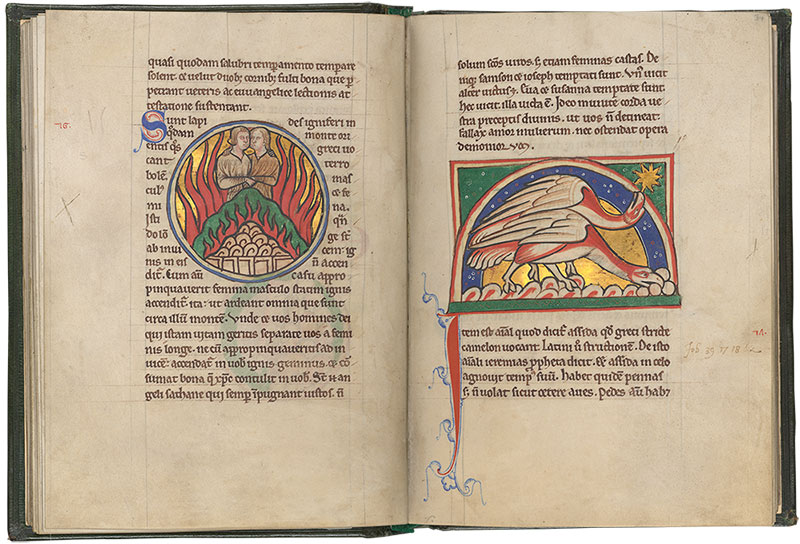

Fire-stones (left)

A man and woman embrace atop a mountain while flames engulf them. These are representations of fire-stones—male and female stones that, when brought together, generate a fire that devours everything in the vicinity.

Ostriches (right)

Ostriches bury their eggs to be hatched by the hot sand so they can turn their attention to the light of God, symbolized by the sun.

MS M.81, fols. 34v–35r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

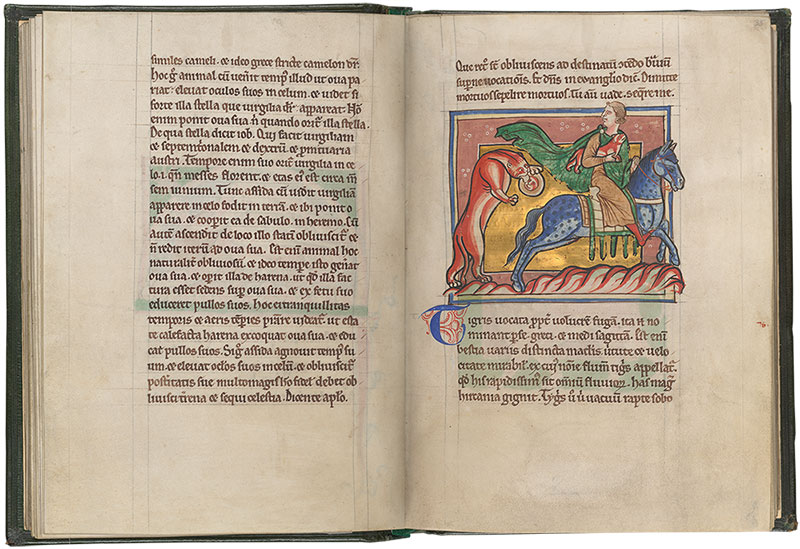

Tiger

A man steals a tiger cub and escapes from its mother by distracting her with a mirror, which she mistakes for her cub.

MS M.81, fols. 35v–36r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

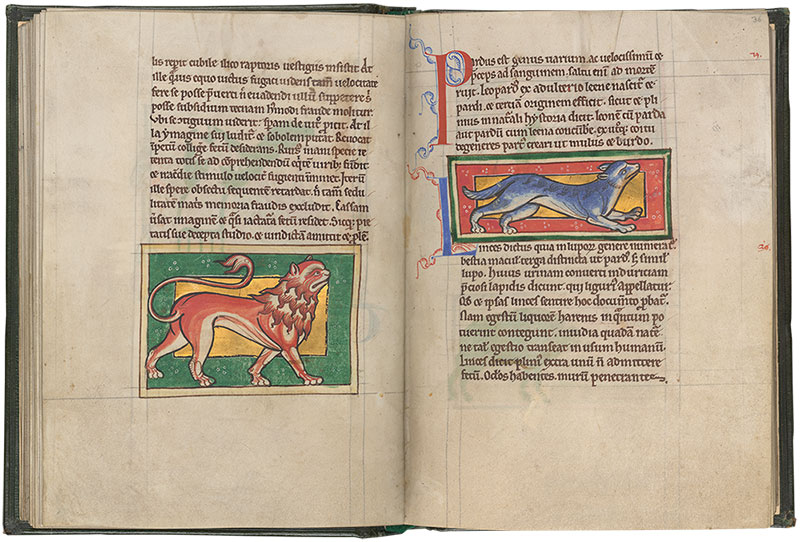

Leopard (left)

Although supposedly a degenerate animal born from the “adulterous” mating of a lioness and a pard, this elegant leopard evokes instead the confident beast featured in the heraldry of many noble families.

Lynx (right)

The bestiary tells us that lynxes like the one pictured here have eyesight sharp enough to penetrate walls.

MS M.81, fols. 36v–37r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

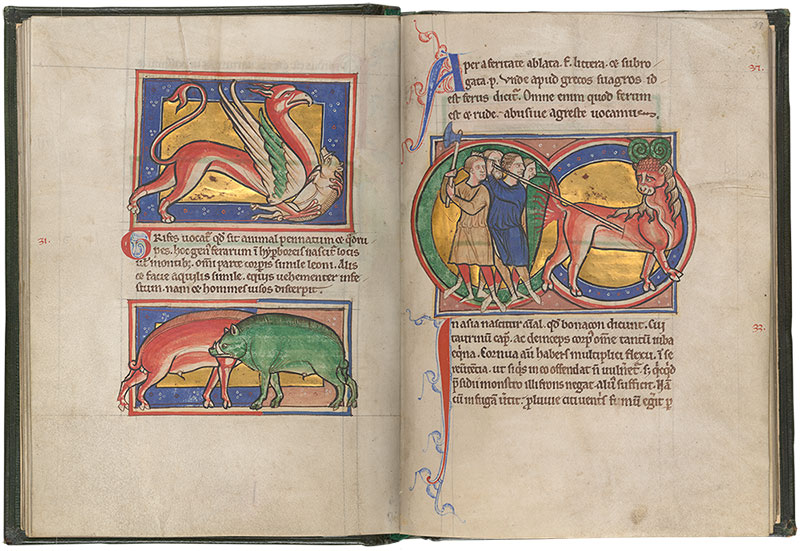

Griffin and Boars (left)

A griffin (part eagle, part lion) carries off a piglet, seemingly unnoticed by the large boars below.

Bonacon (right)

The bonacon (part bull, part horse), defends itself against attackers with a spray of burning feces.

MS M.81, fols. 37v–38r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

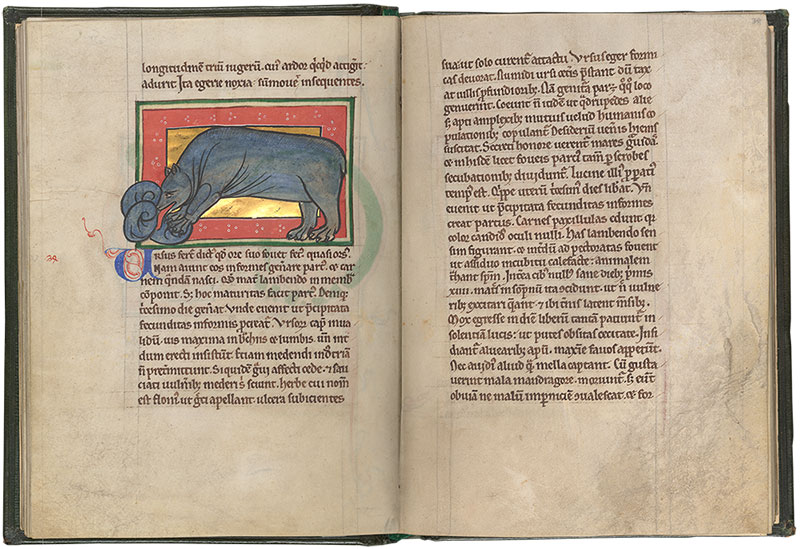

Bear

A mother bear licks her blind and formless cubs into shape—an allegorical reference to the creation of Adam.

MS M.81, fols. 38v–39r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

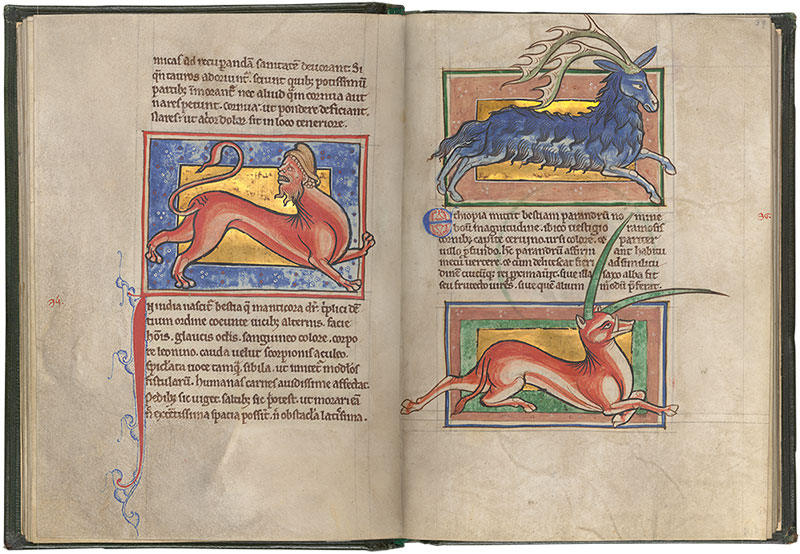

Manticore (left)

A manticore (part man, part lion, part scorpion) is shown as an ugly stereotype signaled by the Phrygian cap associated with eastern peoples, and which medieval readers may also have associated with Jews.

Parandrus and Yale (right)

This folio features two fabled creatures from foreign lands: an extravagantly antlered parandrus, and a yale (eale), able to move its dangerous horns independently.

MS M.81, fols. 39v–40r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

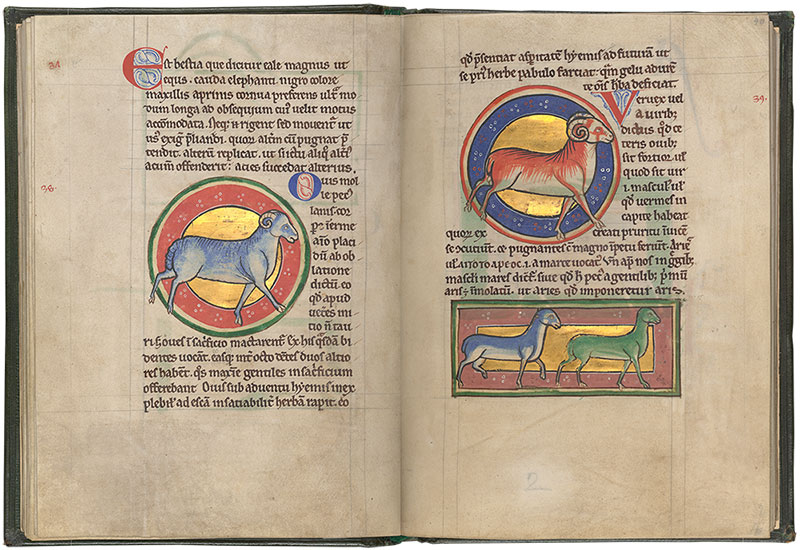

Sheep (left)

This blue sheep illustrates an animal described in the text as “peaceful in spirit.”

Ram (right)

The bestiary speculates that rams may head butt each other because of itchy worms in their scalps. Below, lambs march across the page, serving as model followers of Christ.

MS M.81, fols. 40v–41r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Goat (left)

The he-goat’s pupil may be shown in the corner of its eye because this animal’s eyes were thought to be so full of lust that they always look sideways.

Bull (right)

This bull or a bullock (young bull) was thought to have skin so thick that arrows could not penetrate it, and a mouth that can open as wide as its head.

MS M.81, fols. 41v–42r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

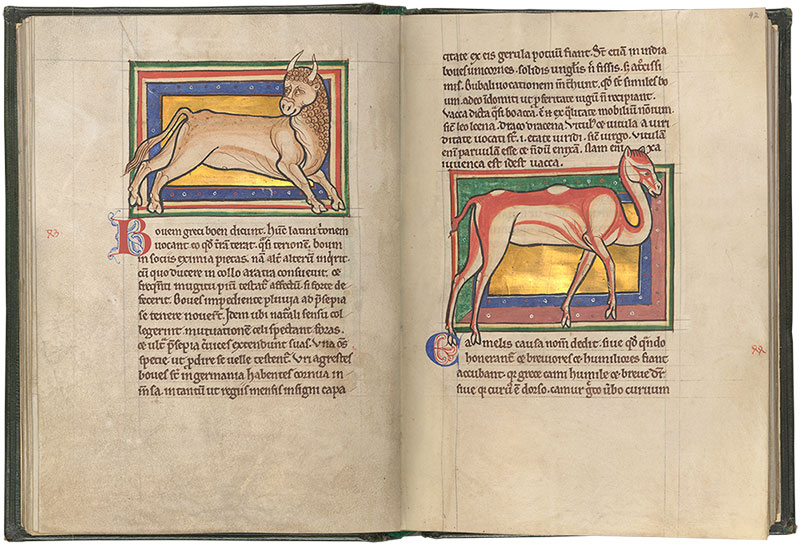

Ox (left)

The majestic bovine creature pictured here is either a tawny Indian bull with curly hair or an affectionate and loyal ox (both described in nearby texts),

Camel (right)

This is an Arabian camel with two humps and cloven hooves that the bestiary claims never wear down, even with excessive walking.

MS M.81, fols. 42v–43r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

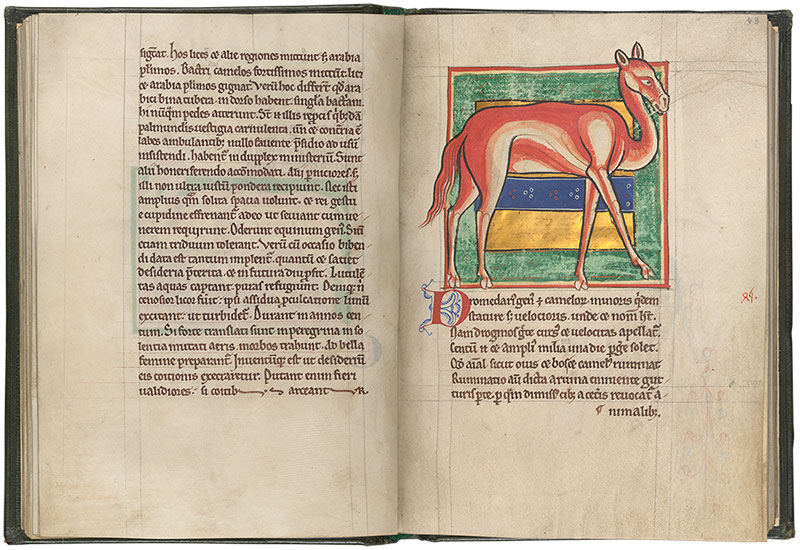

Dromedary

According to the bestiary, the dromedary, shown here without humps, is much like a camel, but smaller and faster, able to travel a hundred miles in a day.

MS M.81, fols. 43v–44r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

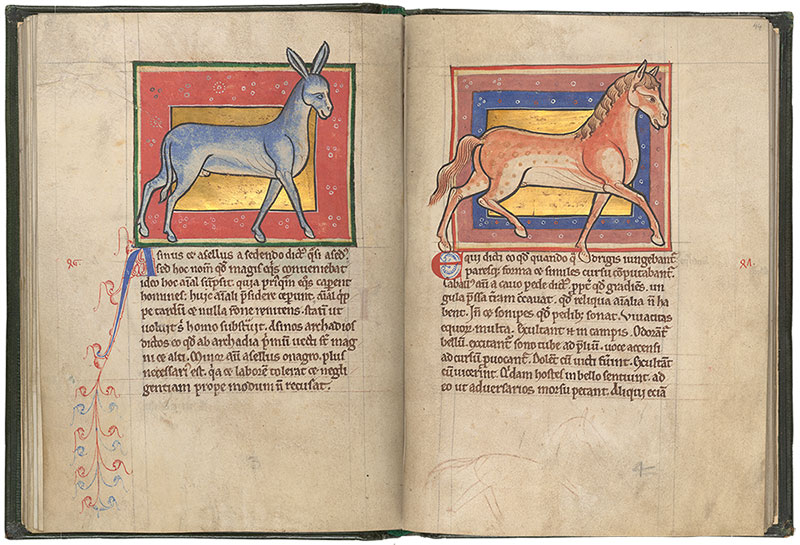

Donkey (left)

The donkey, shown here with its ears pricked and its thin tail between its legs, is a beast of burden and symbol of humility.

Horse (right)

This horse exhibits the desirable features of well-bred horses described in the text: tall, strong, solid-bodied, with a spirited gait, and sharply pointed ears.

MS M.81, fols. 44v–45r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 45v–46r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 46v–47r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

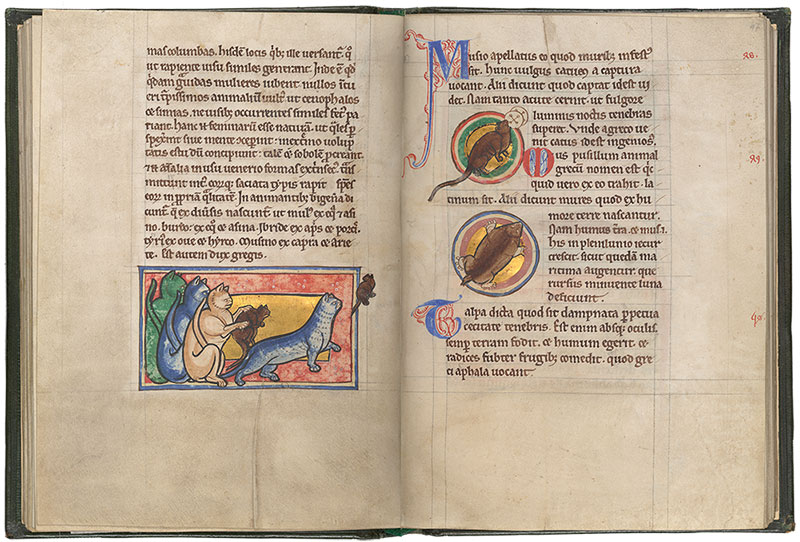

Cats (left)

Although one frightened mouse has managed to scamper out of the frame, the cat’s alert posture leaves little doubt that the predator will catch its prey.

Mouse and Mole (right)

The first rodent featured on this folio is a mouse nibbling at Eucharistic wafers, apparently proving the need for the cats on the previous folio. The second rodent is a top-down view of a mole.

MS M.81, fols. 47v–48r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

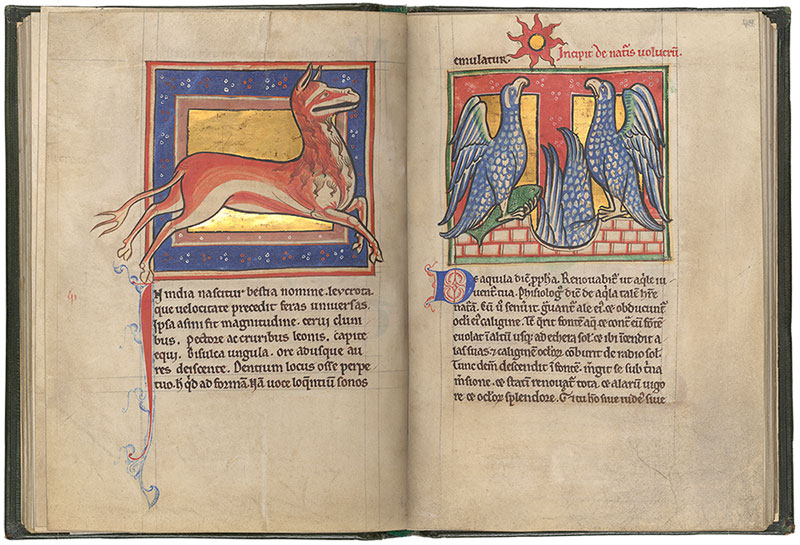

Leucrotta (left)

The fabled leucrotta galloping across this folio has the chest and mane of a lion, the cloven hooves of a camel or dromedary, and a horse’s head.

Eagles (right)

An eagle flies to the sun before plunging into a fountain—a ritual thought to restore the youth of the majestic birds, and which symbolizes baptism.

MS M.81, fols. 48v–49r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

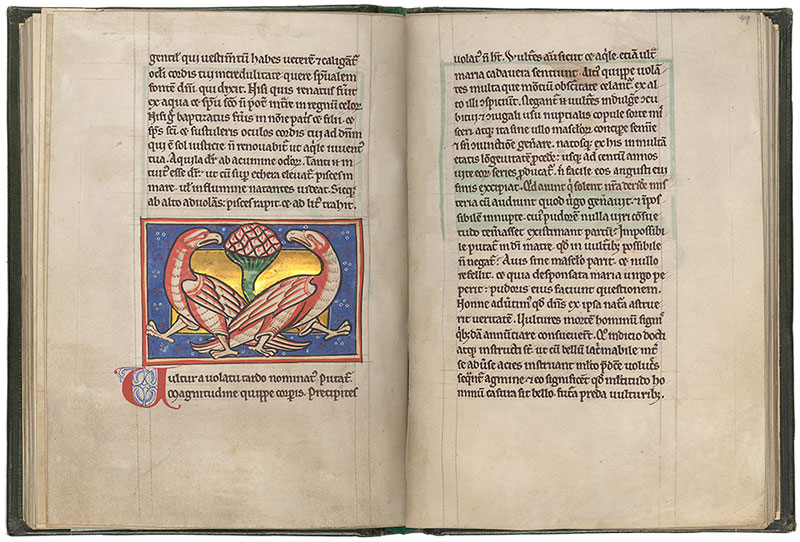

Vultures

Thought to be capable of conceiving without copulation, vultures could symbolize the Immaculate Conception; as carrion-eaters, however, they could also symbolize sinners who follow the Devil.

MS M.81, fols. 49v–50r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

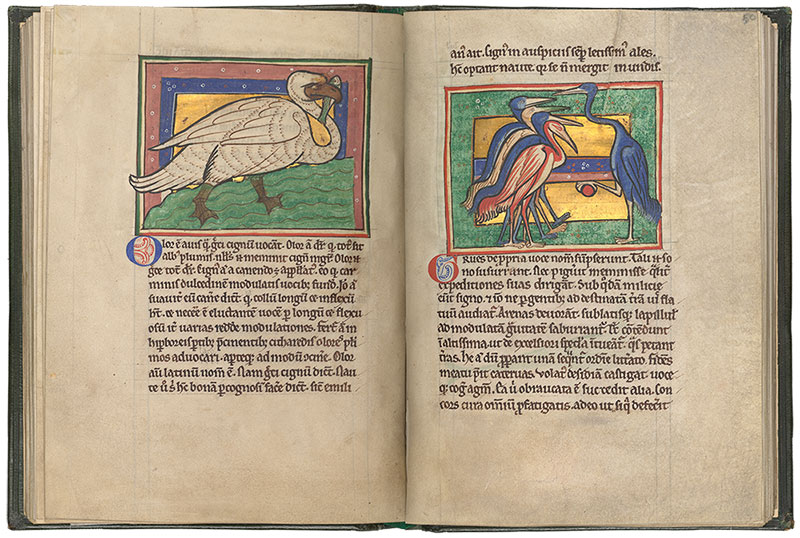

Swan (left)

Swans, like the one here shown swimming confidently with a fish in its beak, were considered good omens by sailors because of their buoyancy.

Cranes (right)

This crane demonstrates its vigilance during the night watch by holding a red stone in its claw, which would startle the bird awake if it becomes sleepy and drops it.

MS M.81, fols. 50v–51r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

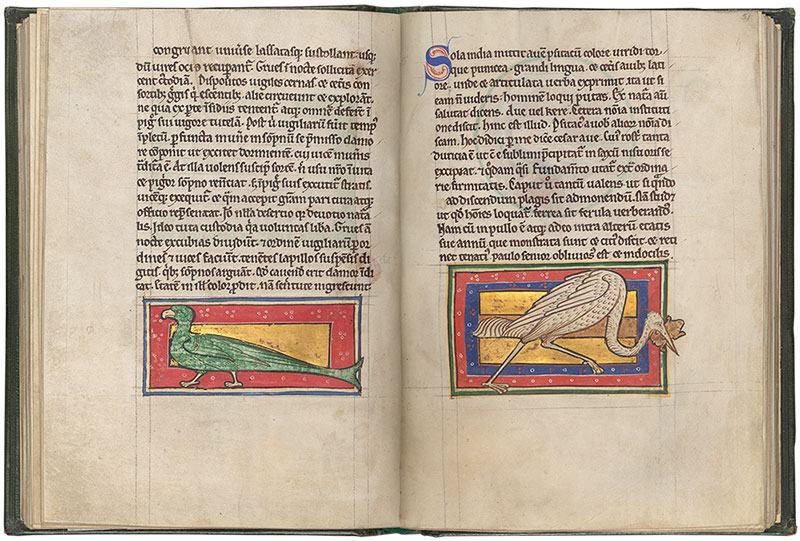

Parrot (left)

The illuminator emphasizes the exotic parrot’s long tail and bright green coloring described in the text.

Stork (right)

This stork has stretched its long neck outside the frame to capture a frog, possibly intended for its offspring, as storks were known to be model parents.

MS M.81, fols. 51v–52r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

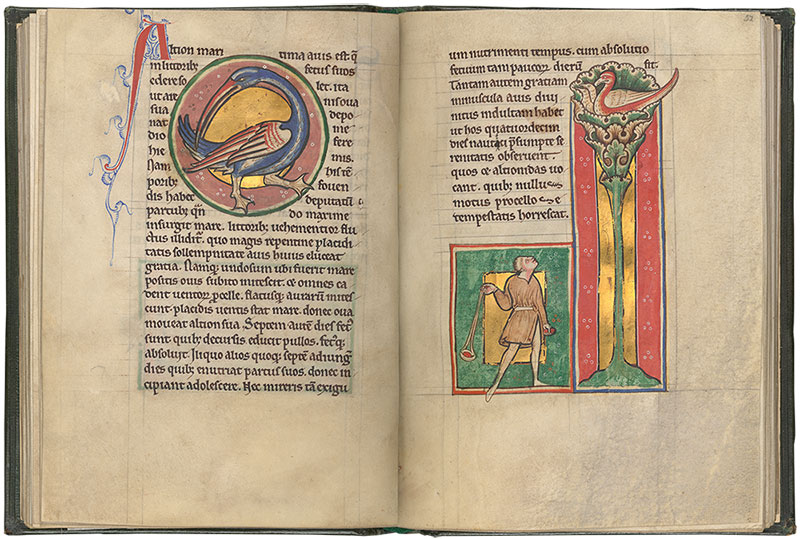

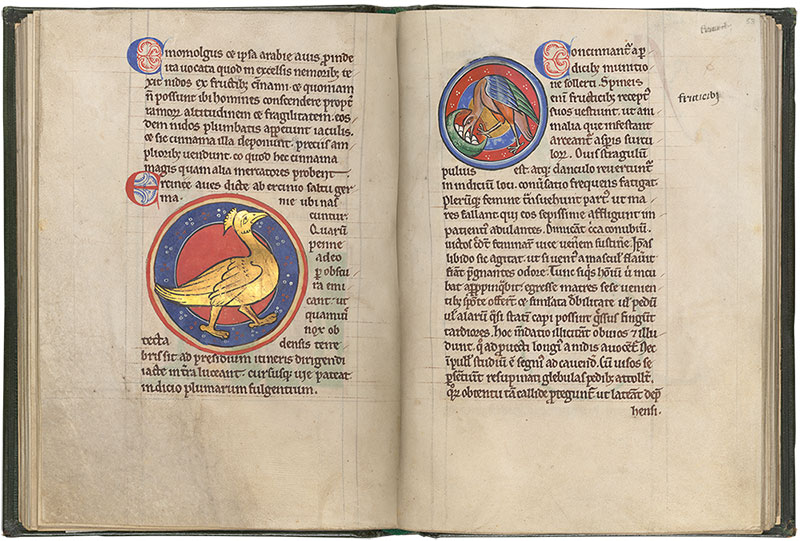

Halcyon (left)

The seas were thought to calm for fourteen days after the halcyon lays its eggs on the shore, which is why sailors refer to fair weather as halcyon days.

Cinnamon Bird (right)

A man with a slingshot is trying to dislodge twigs from the upper branches of a cinnamon tree to harvest the precious spice.

MS M.81, fols. 52v–53r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Ercinea (left)

The Ercinea is a bird thought to have glowing feathers, whose luminosity is emphasized here by gold leaf applied against a contrasting red and blue medallion.

Partridge (right)

The partridge here is likely carrying off her eggs to hide them from male partridges, which “often harm them.”

MS M.81, fols. 53v–54r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

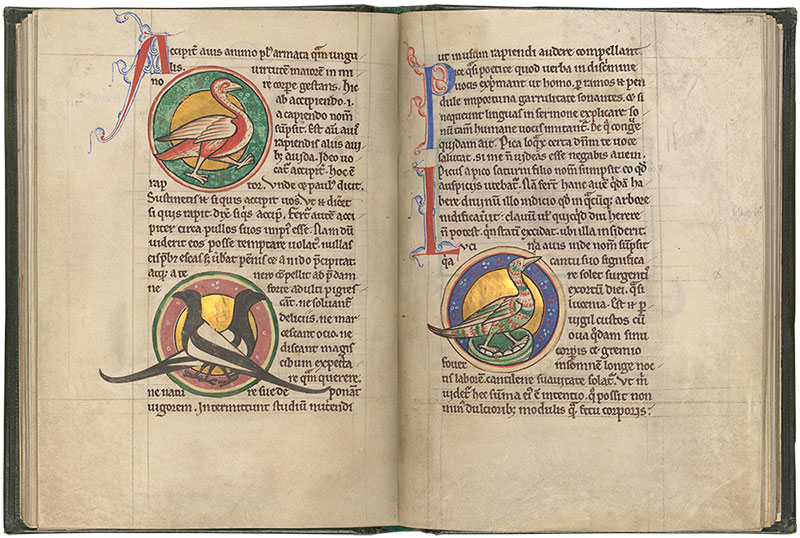

Hawk and Magpies (left)

The hawk in this green and gold medallion is described as a stern parent who forces its chicks to hunt from an early age. Below, a pair of magpies known for their “rude prating” extend their tails into the text and margin.

Nightingale (right)

The multi-colored nightingale warms her eggs in a medallion suggestive of a moon or glowing dawn, evoking the time when the nocturnal bird sings its sweet song.

MS M.81, fols. 54v–55r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

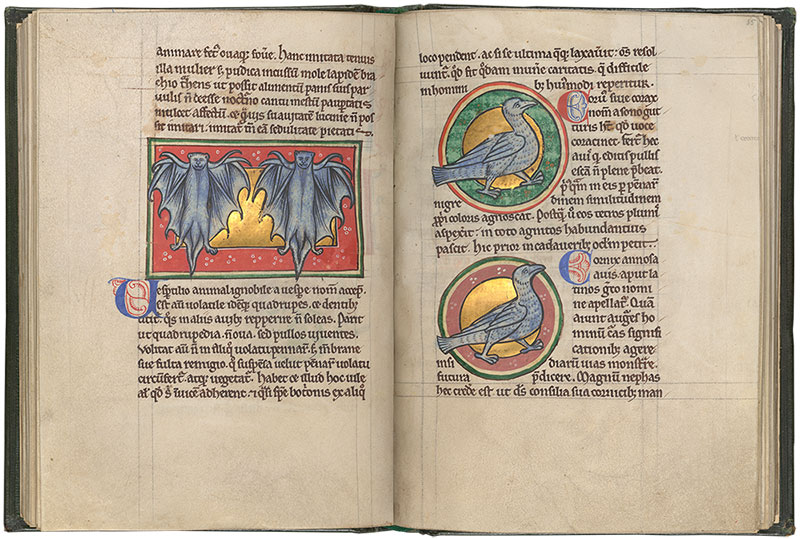

Bats (left)

Included in the section on birds, the bats here display their distinctive characteristics with membranes spread and four feet.

Raven and Crow (right)

Although shown as strikingly similar, the bestiary tells us that the raven refuses to feed its young until it sees their feathers are the same color as its own, while the crow shown below is described as an exemplary parent.

MS M.81, fols. 55v–56r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

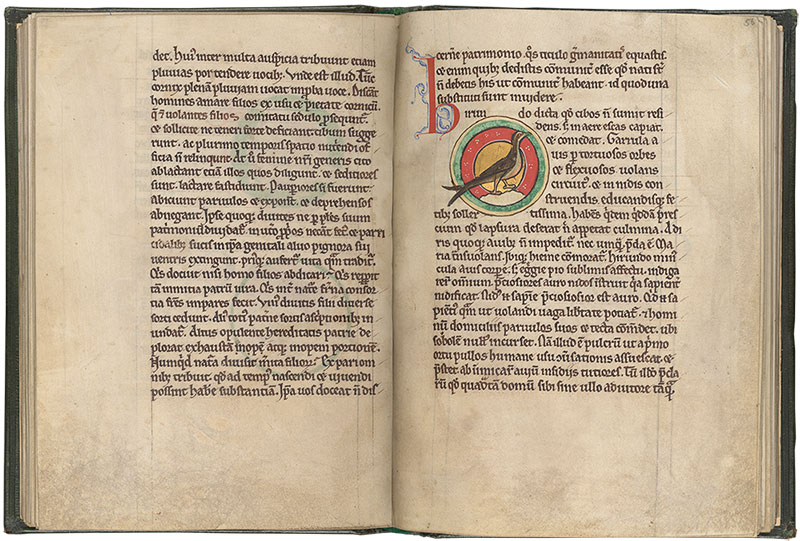

Swallow

The swallow, shown perched on a white patch suggesting a cloud, was thought to capture and eat its prey in the air, like those who reject earthly possessions for the things of heaven.

MS M.81, fols. 56v–57r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Quail (left)

The bestiary tells us that the quail, depicted here with red and green feathers, was a migratory bird that suffers from the falling sickness (epilepsy), and eats poisonous seeds.

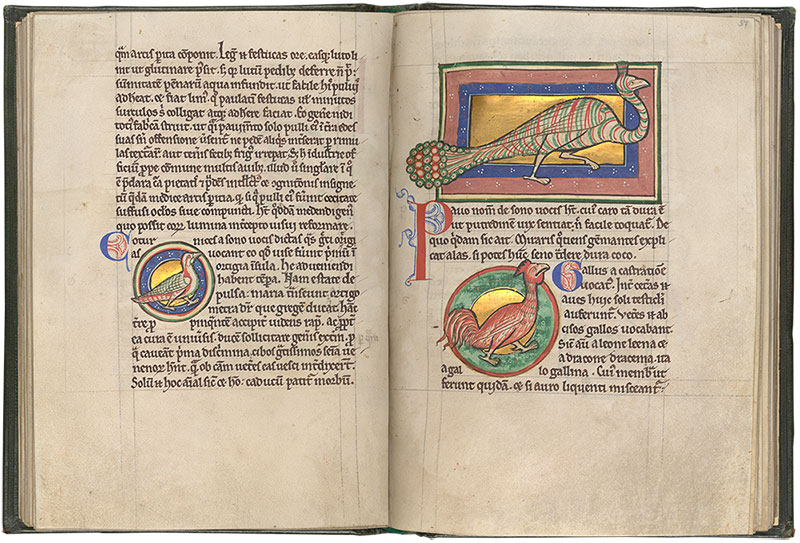

Peacock and Cock (right)

This peacock may reflect comparisons of the bird with tail open to prideful preachers, and the advice offered by bestiaries that the peacock “keep its tail down.” Below, a cock illustrates a description of the power of the cock’s crow, thought to calm storms and frighten robbers.

MS M.81, fols. 57v–58r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

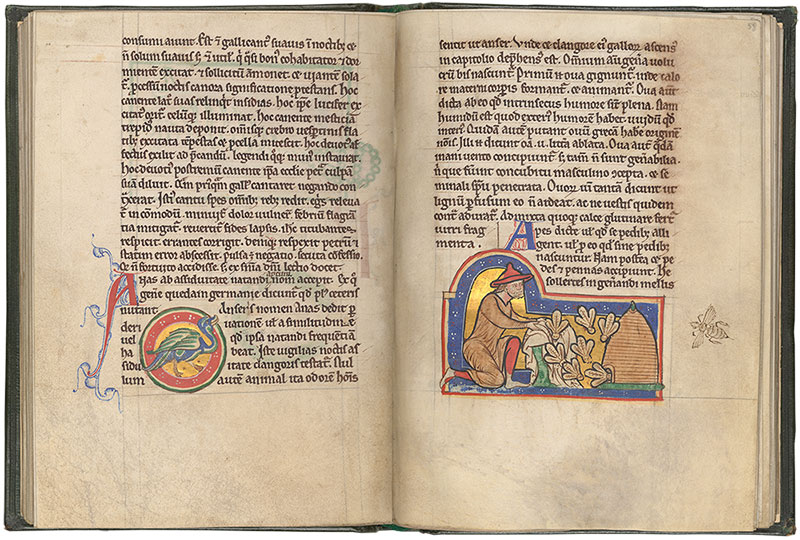

Duck (left)

This cheerful duck illustrates an entry explaining that the word “duck” in Latin (anas) is connected to the fact that they are constantly swimming (natare).

Bees (right)

Categorized as birds, the giant bees shown here were presented to medieval readers as exemplary animals that worked hard for the benefit of community and king.

MS M.81, fols. 58v–59r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 59v–60r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 60v–61r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

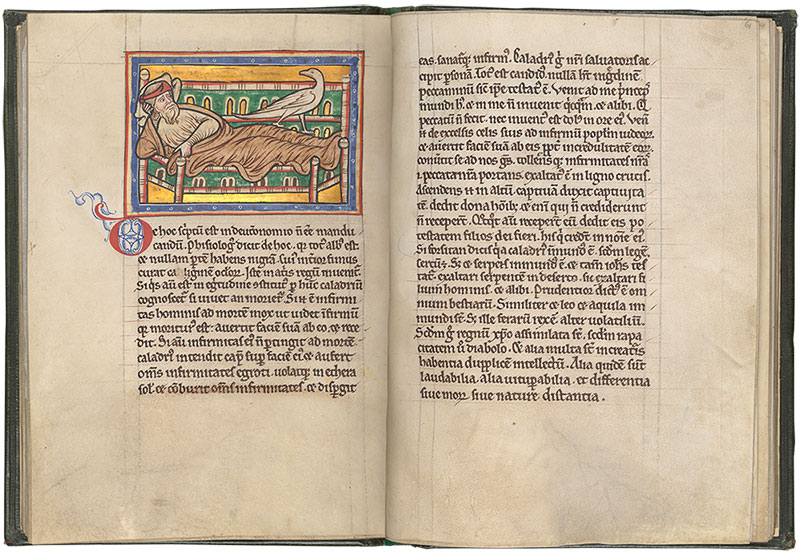

Caladrius

The pure white caladrius bird turns away from a sick person when he is going to die, but if, as here, the bird looks directly at him, it takes on the person’s sickness and burns it off in the sun, thus curing the sufferer.

MS M.81, fols. 61v–62r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

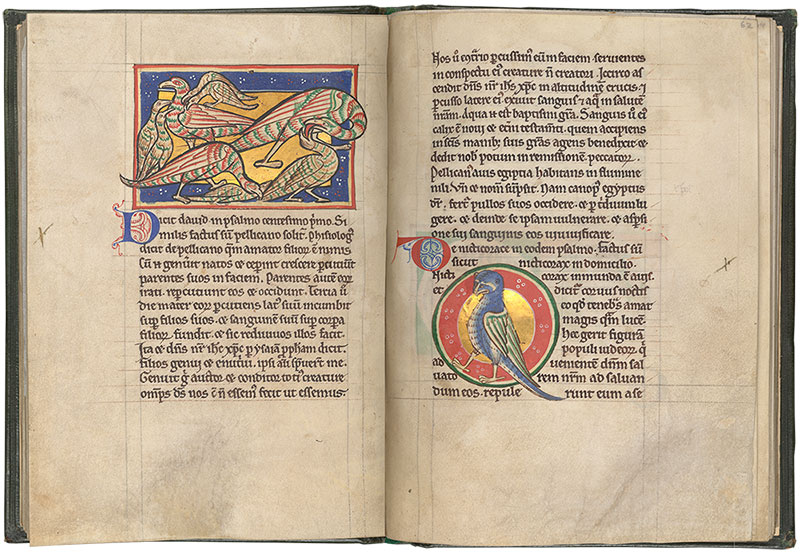

Pelican (left)

Moving counter-clockwise, this illumination represents the mother pelican as a symbol for Christ: first, she is attacked by her chicks (top left), then slays them, and finally revives them by piercing her breast and feeding them her own blood.

Night Raven or Night Owl (right)

The night raven shown here betrays the bestiary’s anti-Semitism when it equates the bird with Jews who reject the light of Christ—though it also connects the bird to Christ, who wants to redeem sinners associated with darkness.

MS M.81, fols. 62v–63r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

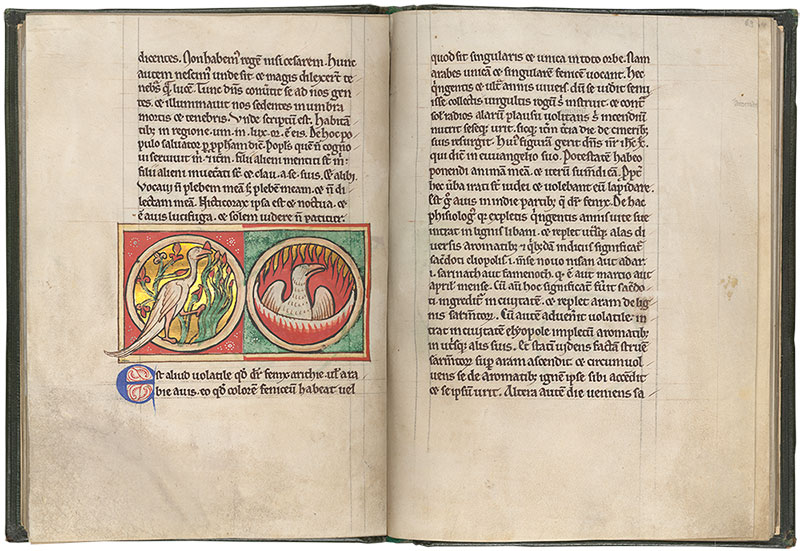

Phoenix

The legendary phoenix’s cycle of death and rebirth symbolizes Christ in the bestiary: on the left, the aged bird gathers sweet-smelling spices to line its funeral pyre; on the right, it rises from the flames.

MS M.81, fols. 63v–64r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

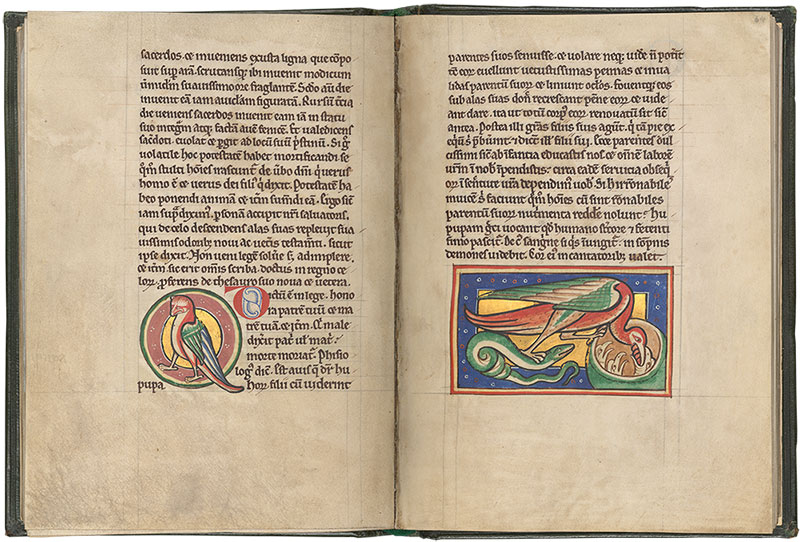

Hoopoo (left)

The hoopoo is described as a filthy animal, living among offal and human waste, but also as an example to humans for the care it takes of its parents.

Ibis (right)

The ibis is shown clutching a serpent while it regurgitates the snake’s eggs to feed its young—a detail not mentioned in the text, but which the illuminator must have known from other bestiaries.

MS M.81, fols. 64v–65r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Coot

This coot is grooming its feathers to reinforce the notion that it is a clean bird; because it was thought to live in one place, it was considered a model for Christians whose permanent home should be the Church.

MS M.81, fols. 65v–66r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Partridge (left)

This vibrant orange partridge illustrates an entry discussing the bird’s alleged lustful and deceitful nature.

Turtle-Doves (right)

The turtle doves are shown paired because they were believed to mate for life—symbolic of the eternal “marriage” of Christ and the Church.

MS M.81, fols. 66v–67r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 67v–68r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

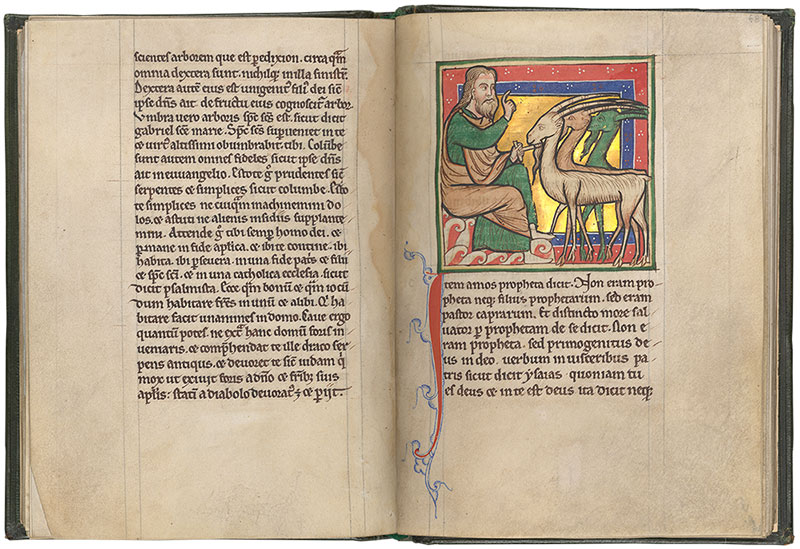

Amos, the Prophet

Here Amos announces his prophecies to an attentive flock of multi-colored goats. An anti-Jewish passage—typical of the text—compares Jews to sinful goats, which Christ was unable to convert into sheep.

MS M.81, fols. 68v–69r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

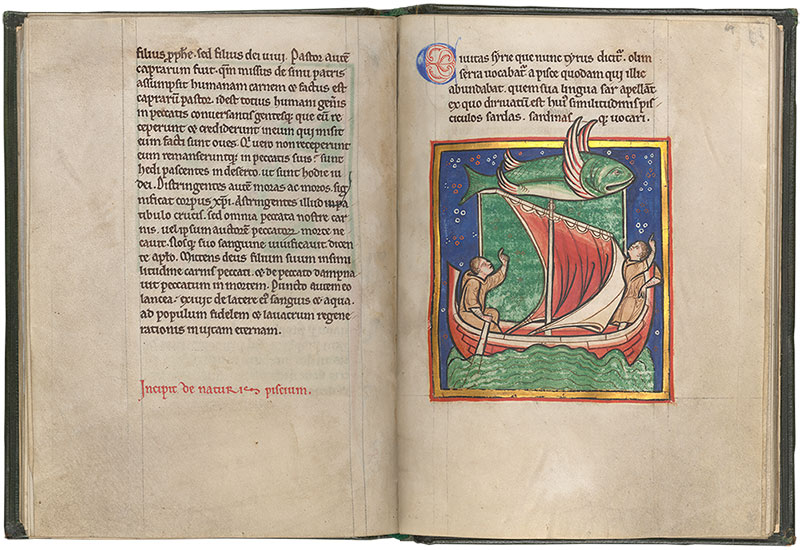

Saw-fish

Here, a saw-fish with immense wings races a ship; when it is exhausted, it will retreat to the sea, representing Christians who start in good faith but are conquered by vice.

MS M.81, fols. 69v–70r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

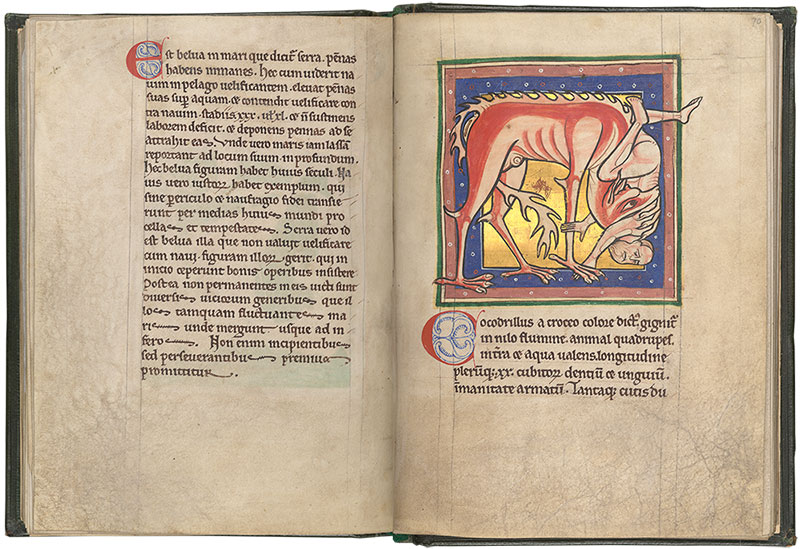

Crocodile

This terrifying ridge-backed beast devouring a corpse is not easily recognizable as a crocodile; after the kill, it weeps over its prey, and is thus an effective symbol of hypocrisy.

MS M.81, fols. 70v–71r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 71v–72r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

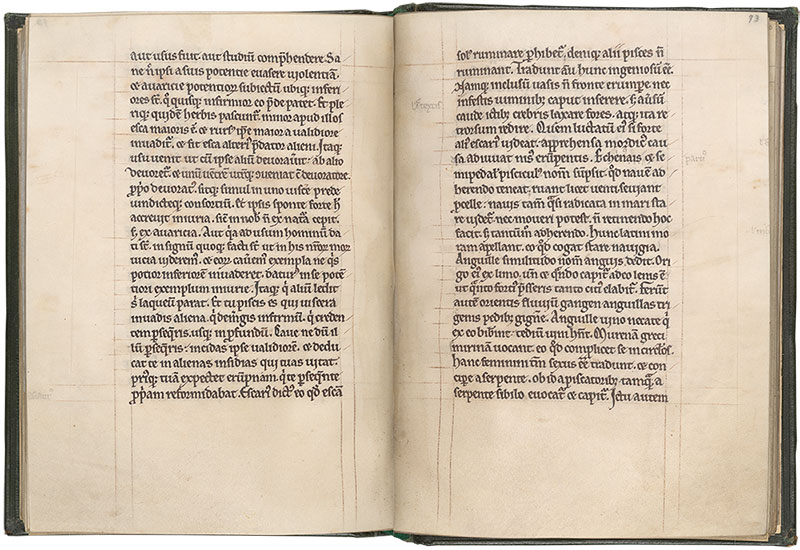

MS M.81, fols. 72v–73r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 73v–74r

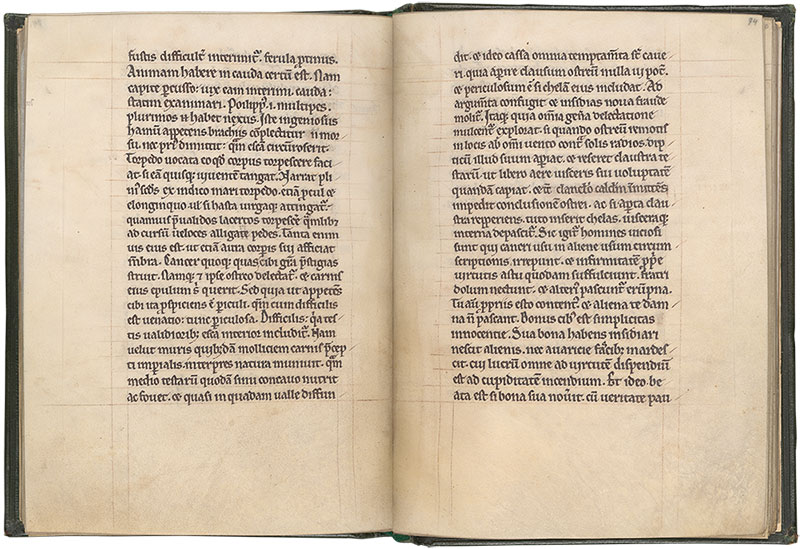

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 74v–75r

Worksop Bestiary

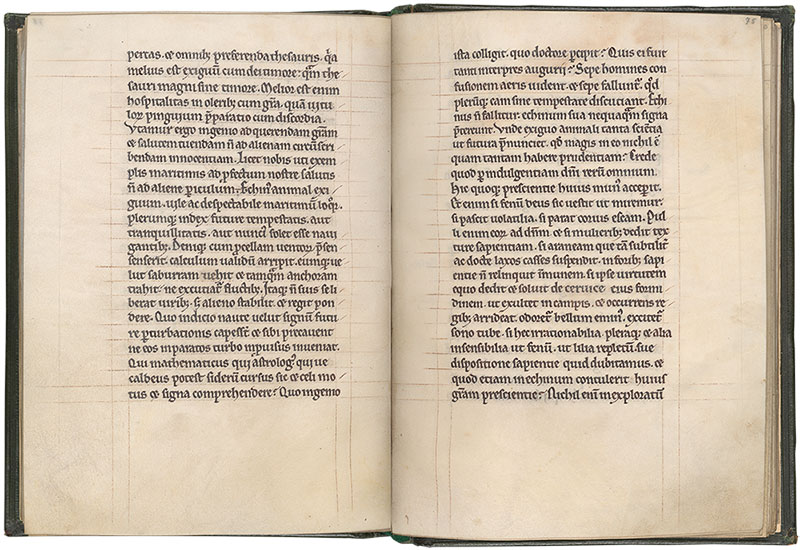

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 75v–76r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

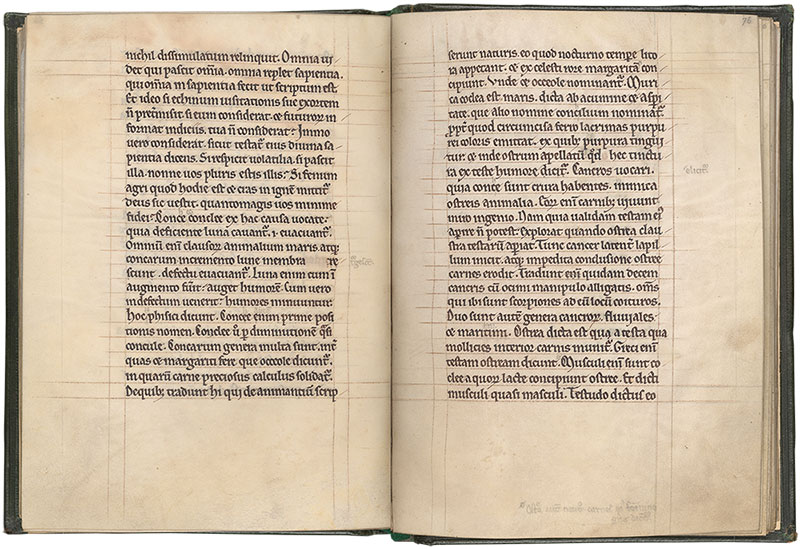

MS M.81, fols. 76v–77r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 77v–78r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

Dragon

The dragon suffocates the elephant by tying it up with deadly knots, identified by the bestiary as being like the Devil, “the most monstrous serpent of all.”

MS M.81, fols. 78v–79r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

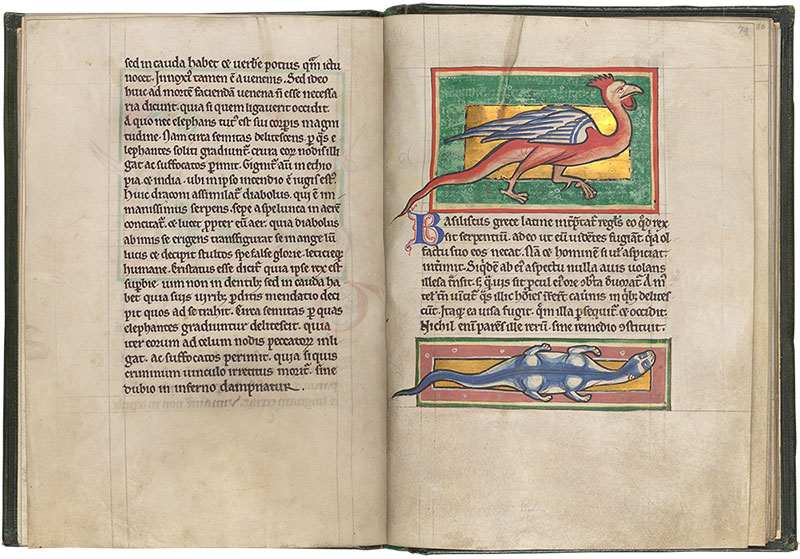

Basilisk and Weasel

The basilisk, a winged snake with the head of a cock, kills by scent alone, and can paralyze its prey with a glance. But, “the Creator has made nothing without a remedy,” and its one natural enemy, the weasel, is pictured on the same folio.

MS M.81, fols. 79v–80r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

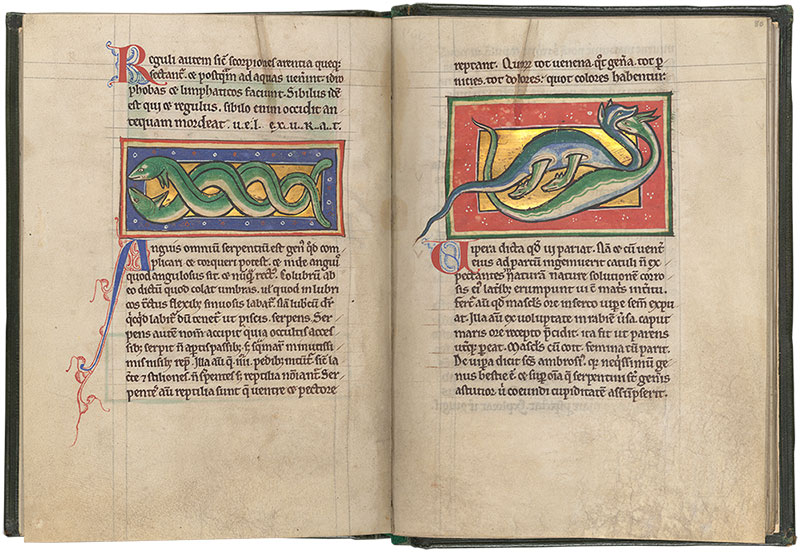

Snakes (left)

Two intertwined serpents introduce an entry on the general qualities of snakes: their bending, shadowy, slippery, poisonous natures.

Viper (right)

This scene illustrates the deadly procreation of vipers: after mating, the female bites off the male’s head, and finally the young gnaw through the female’s belly.

MS M.81, fols. 80v–81r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 81v–82r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

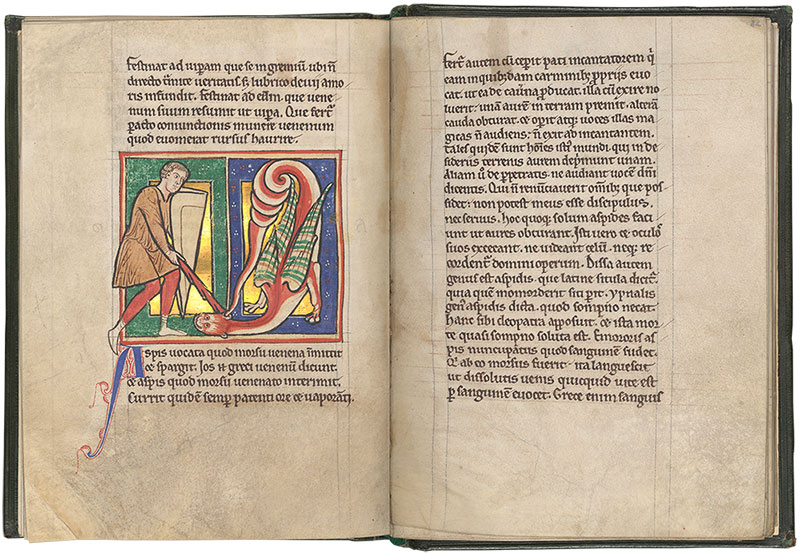

Asp

The venomous asp presses one ear to the ground and plugs its other ear with its tail to resist the deadly allure of the snake charmer.

MS M.81, fols. 82v–83r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

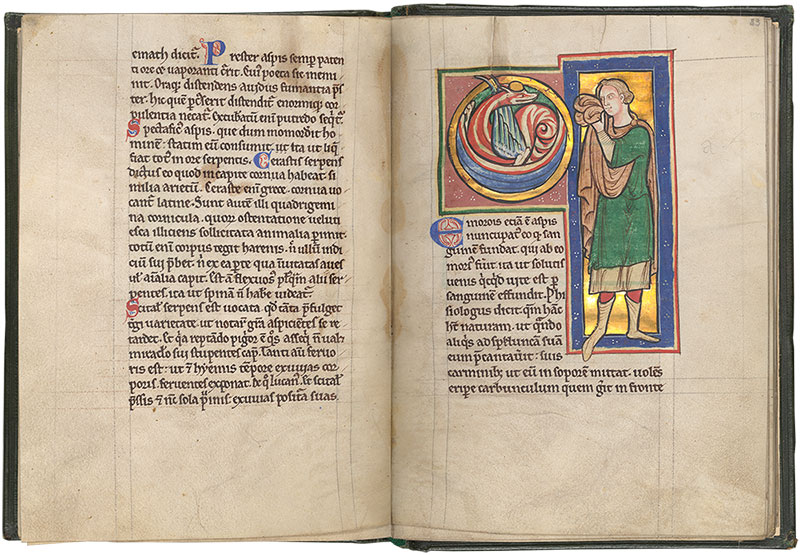

Emorrosis

A covetous man uses the folds of his mantle to try to steal the golden carbuncle guarded by the deadly emorrosis, whose venom makes its victims sweat blood.

MS M.81, fols. 83v–84r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

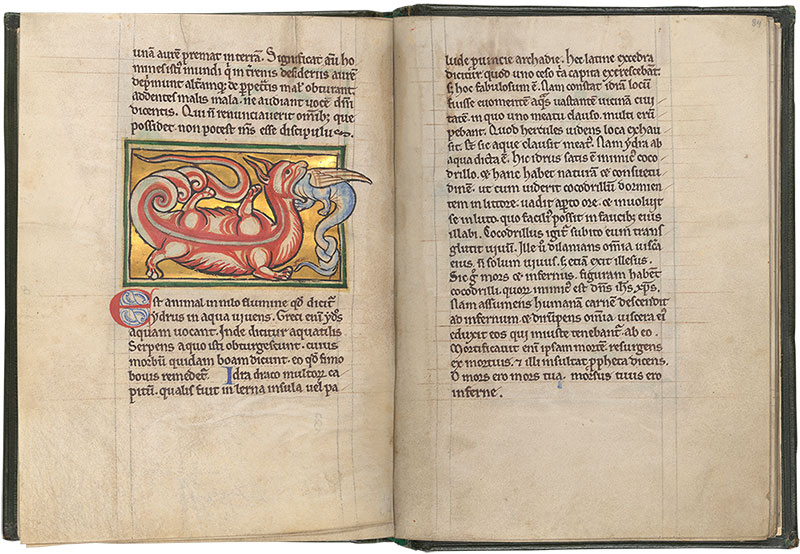

Hydrus

The hydrus lubricates itself with mud and slips down the throat of a crocodile in order to kill it from the inside, as Christ coated himself in human skin and defeated the devil.

MS M.81, fols. 84v–85r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

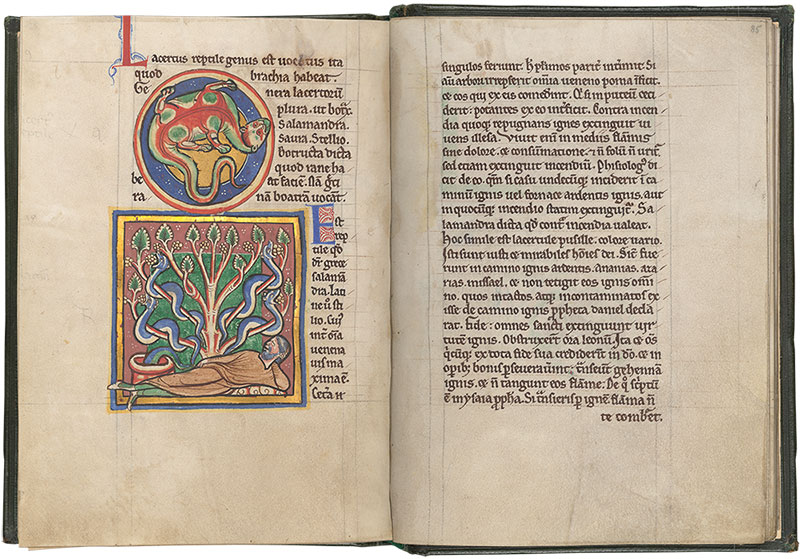

Lizard and Salamanders

An aerial view of a lizard introduces the section. Below, salamanders contaminate an apple tree, with a victim shown at its base.

MS M.81, fols. 85v–86r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

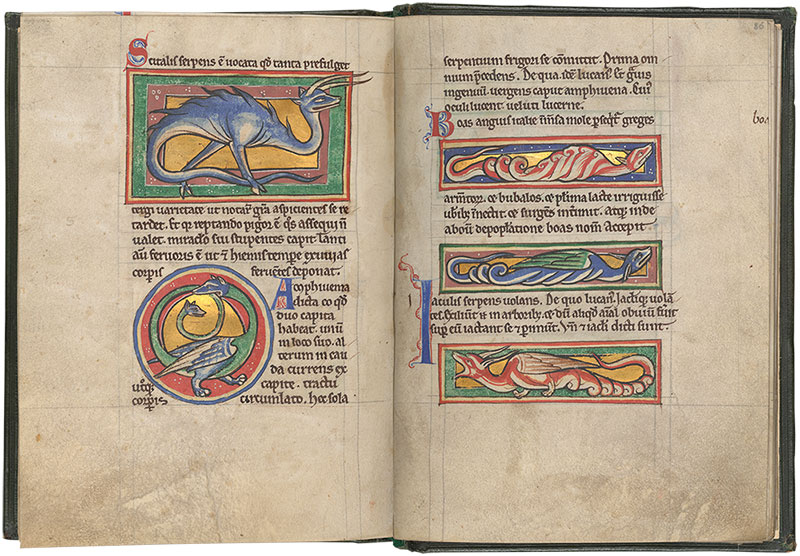

Scitalis and Amphisbaena (left)

The scitalis pictured here is said to stun its prey with its marvelous appearance. Below is the amphisbaena, which has two heads and can move quickly with either head in the lead.

Boa, Jaculus, and Syren (right)

Each of these illuminations displays a different type of snake: the boa kills cattle by drinking from their udders; the jaculus launches itself from trees; and the syren is faster than a horse.

MS M.81, fols. 86v–87r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

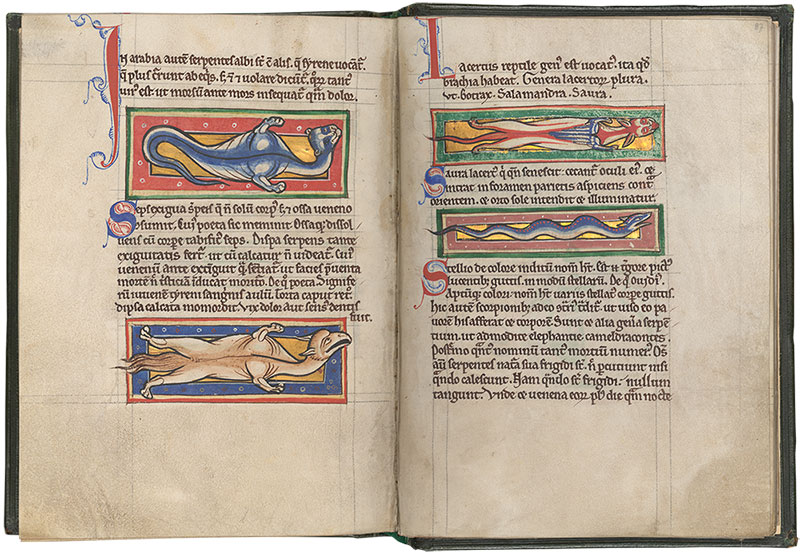

Seps and Lizard (left)

The animal above is a slithery blue seps, whose venom destroys flesh and bone. Below is described as a lizard, despite its bushy tail and hooked beak.

Saura and Stellio (right)

Above is a winged saura: a lizard, which can cure its blindness by gazing towards the rising sun through a crack in a wall. Below is the stellio, a type of spotted newt.

MS M.81, fols. 87v–88r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

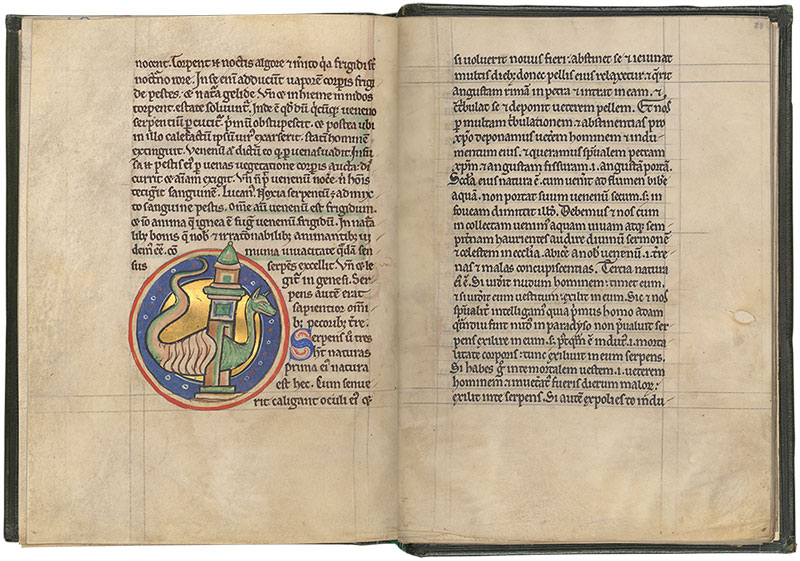

Molting Serpent

Beginning a long section on the “nature of serpents,” this miniature illustrates how a snake molts: it sloughs off its skin by scraping its body against the walls of a narrow slit in a rock (or, in this case, gate) as Christians are urged to slough off their sinful selves with Christ’s help.

MS M.81, fols. 88v–89r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

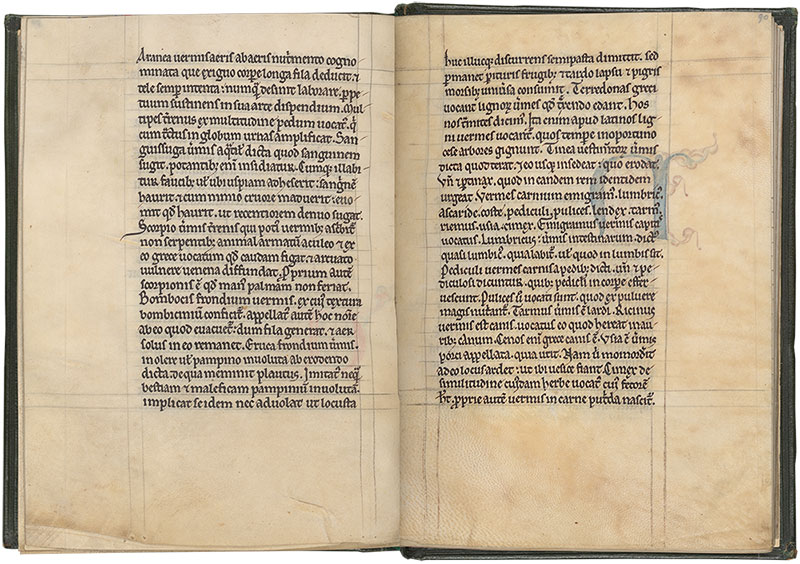

MS M.81, fols. 89v–90r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

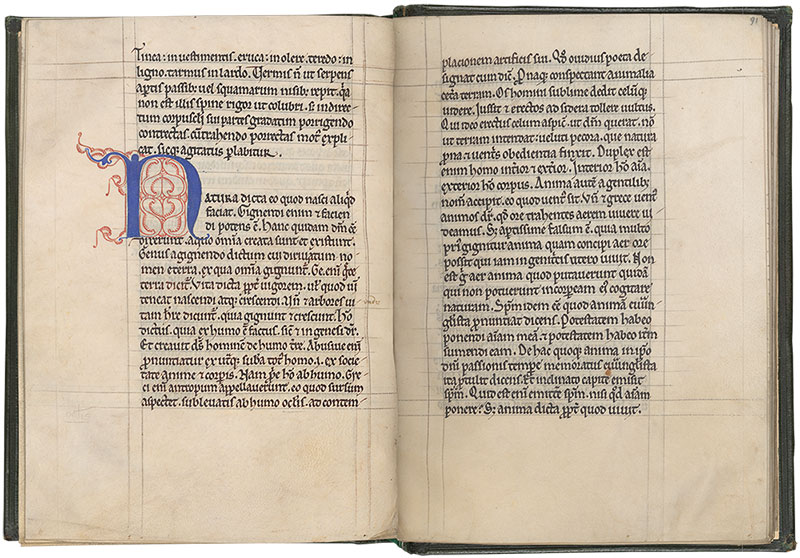

MS M.81, fols. 90v–91r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

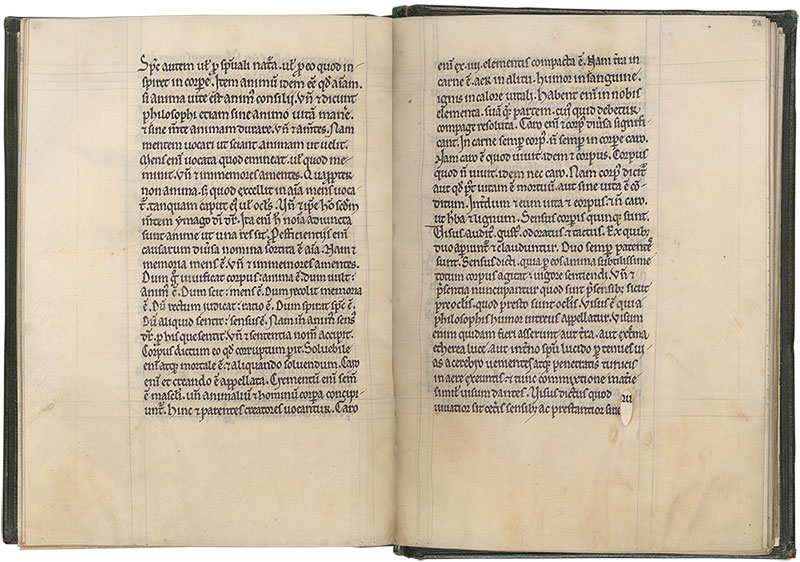

MS M.81, fols. 91v–92r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

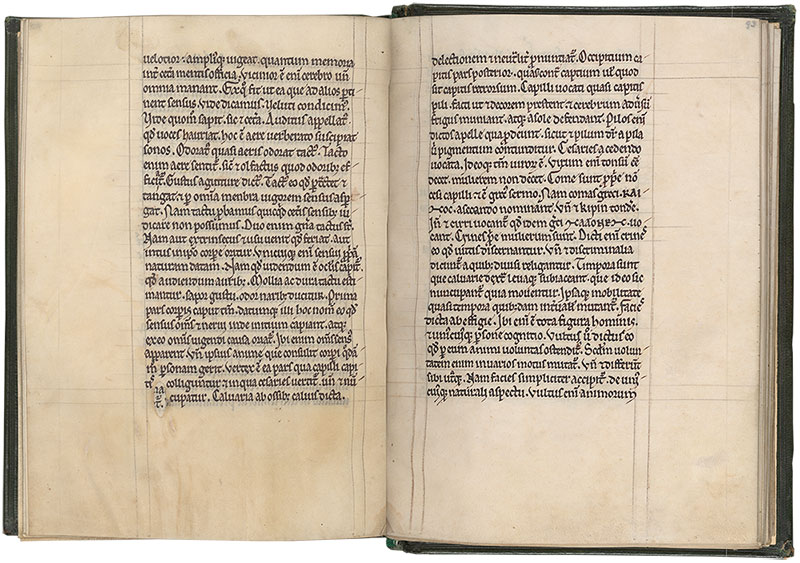

MS M.81, fols. 92v–93r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

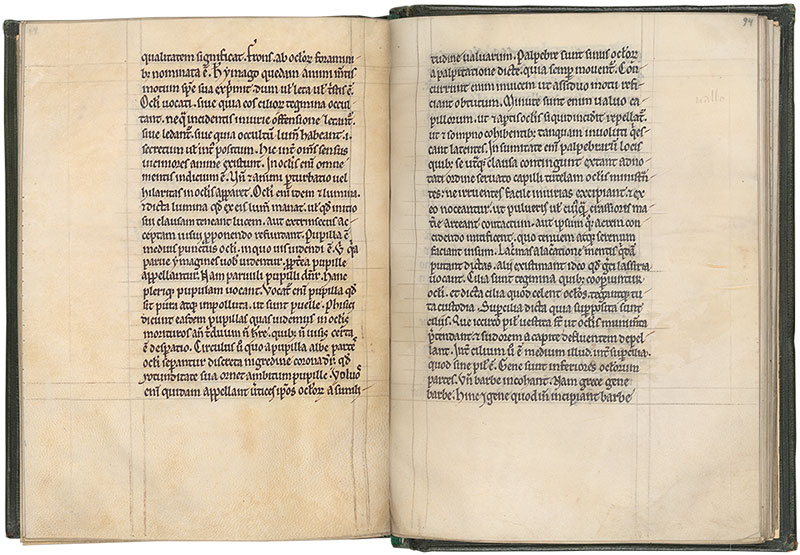

MS M.81, fols. 93v–94r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 94v–95r

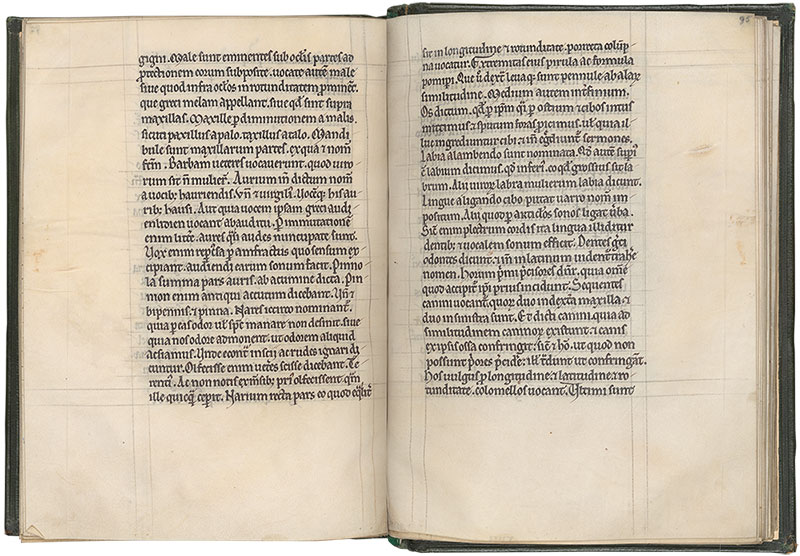

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

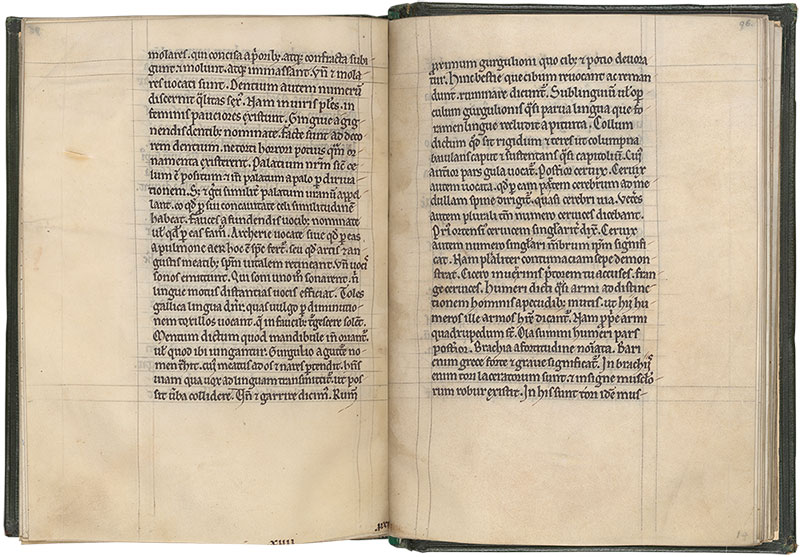

MS M.81, fols. 95v–96r

Worksop Bestiary

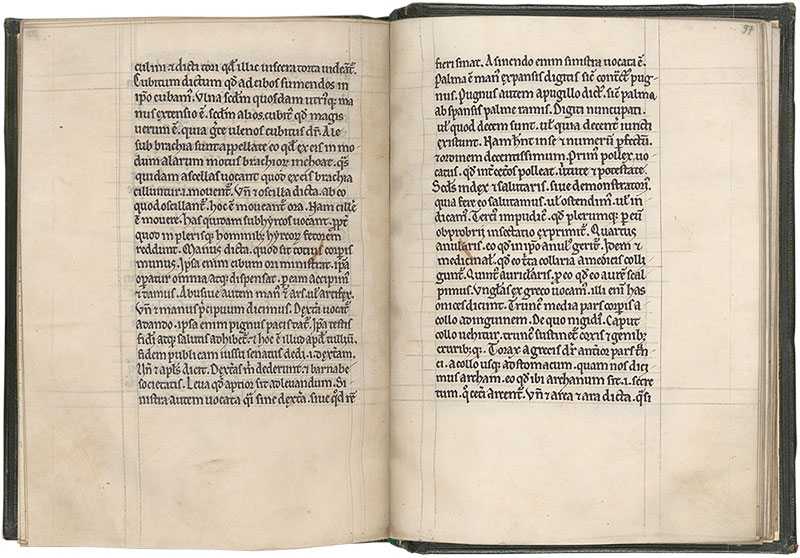

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 96v–97r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 97v–98r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 98v–99r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 99v–100r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 100v–101r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 101v–102r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 102v–103r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 103v–104r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 104v–105r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

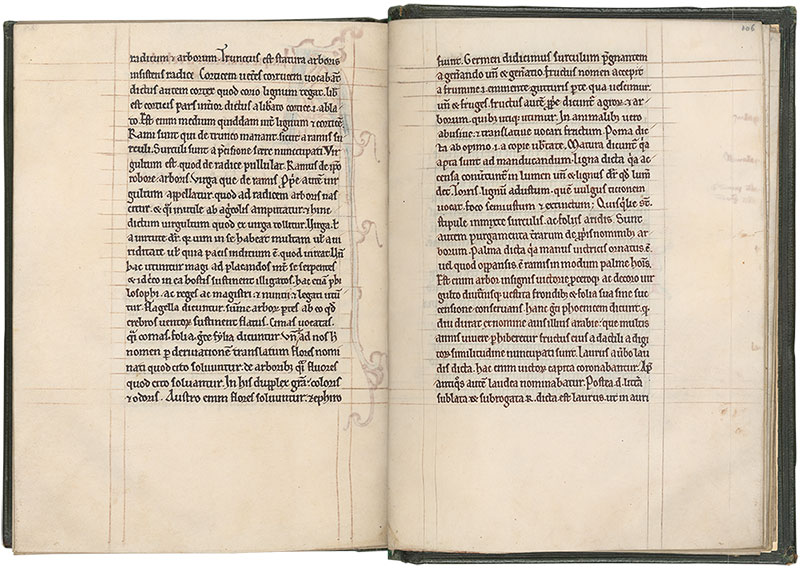

MS M.81, fols. 105v–106r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 106v–107r

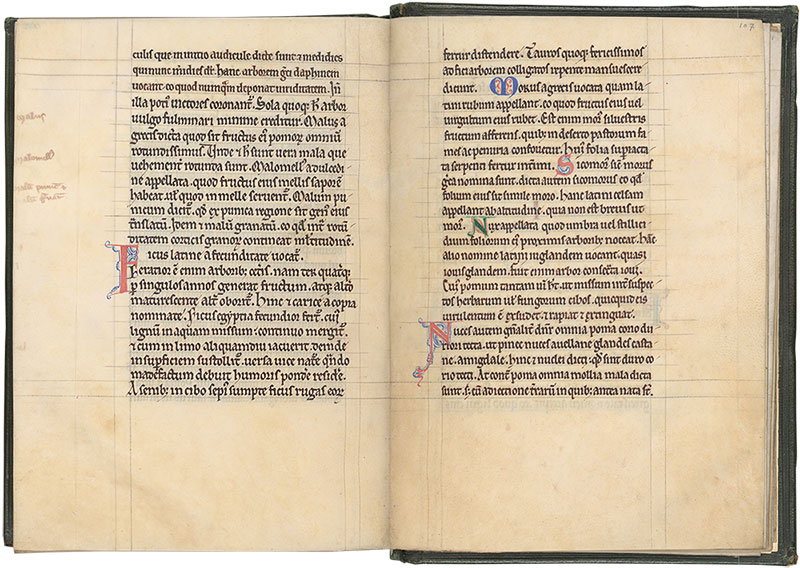

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 107v–108r

Worksop Bestiary

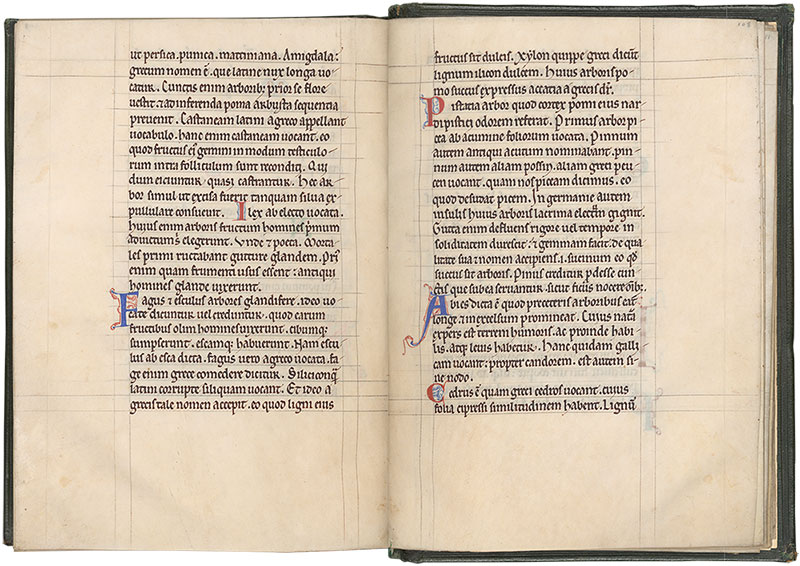

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 108v–109r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

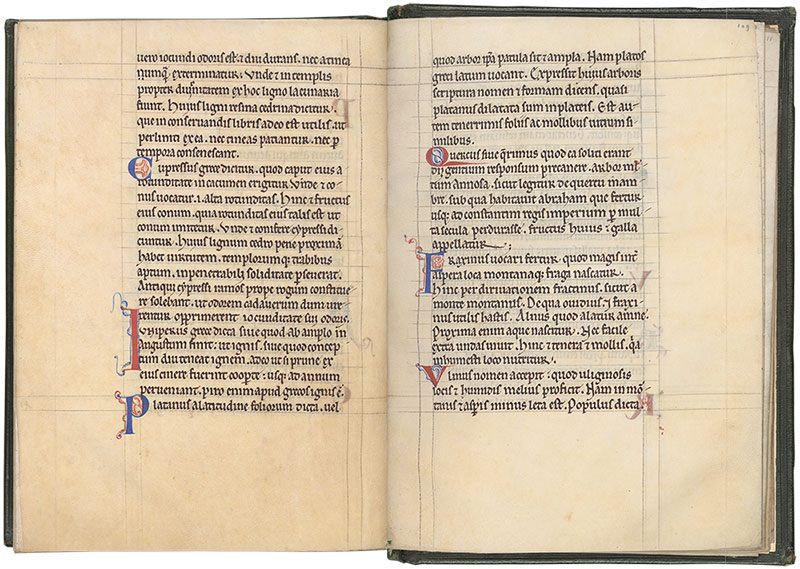

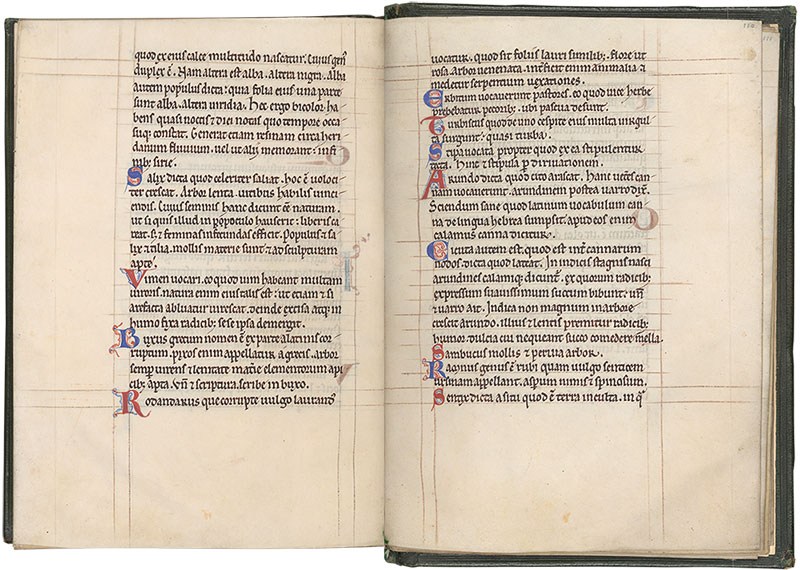

MS M.81, fols. 109v–110r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 110v–111r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

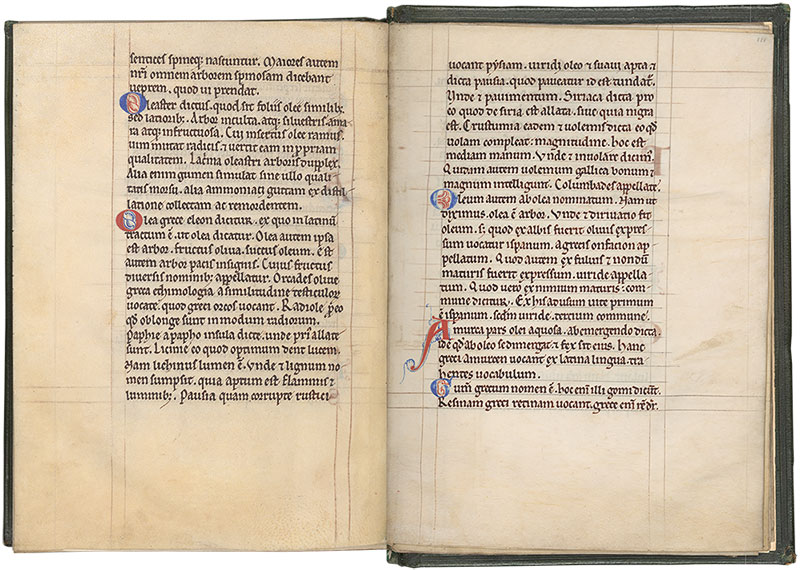

MS M.81, fols. 111v–112r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

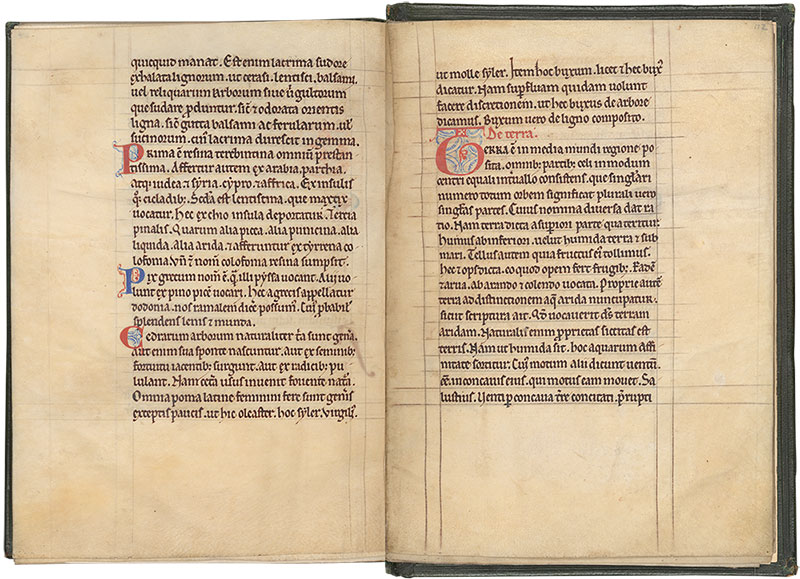

MS M.81, fols. 112v–113r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

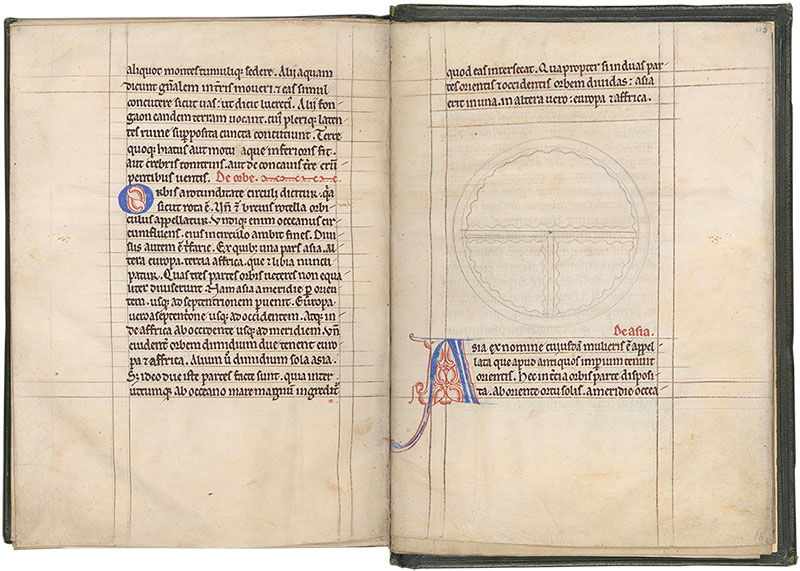

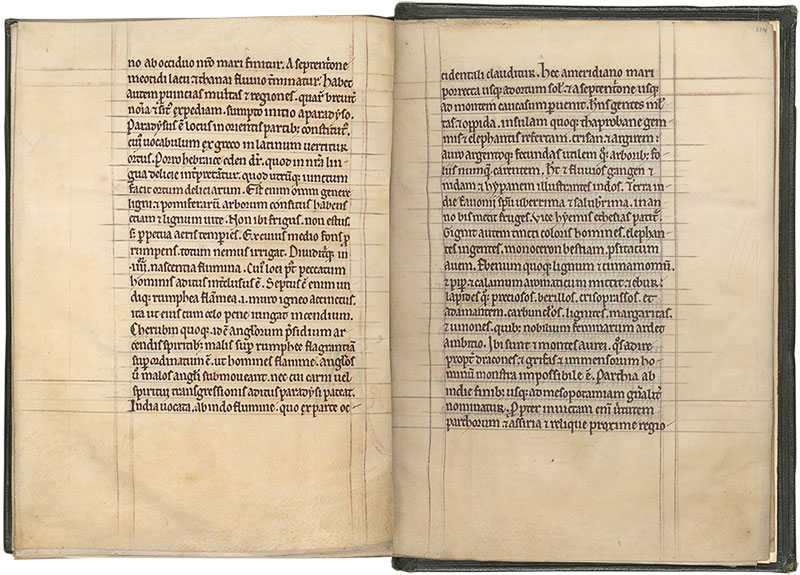

MS M.81, fols. 113v–114r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 114v–115r

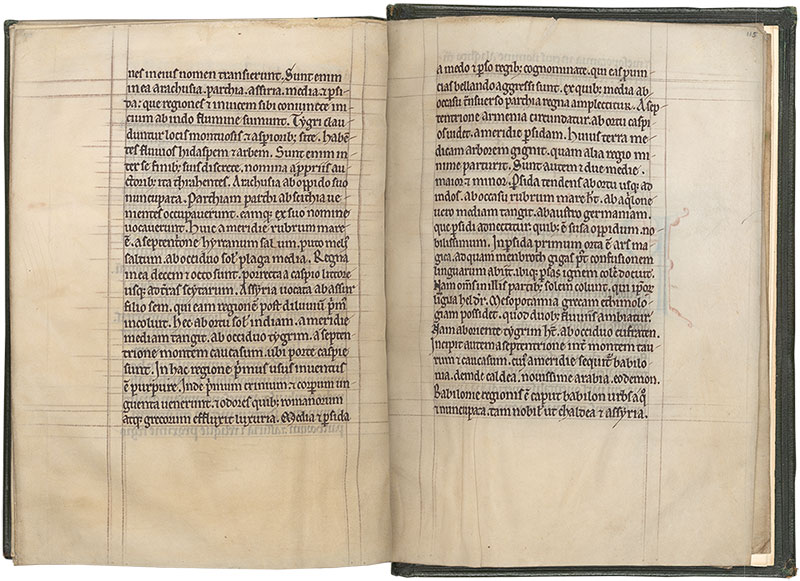

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 115v–116r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 116v–117r

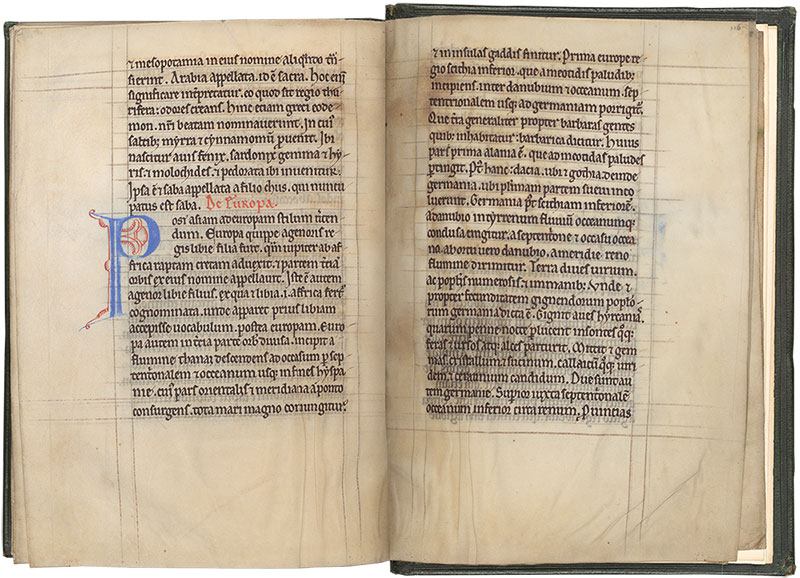

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 117v–118r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 118v–119r

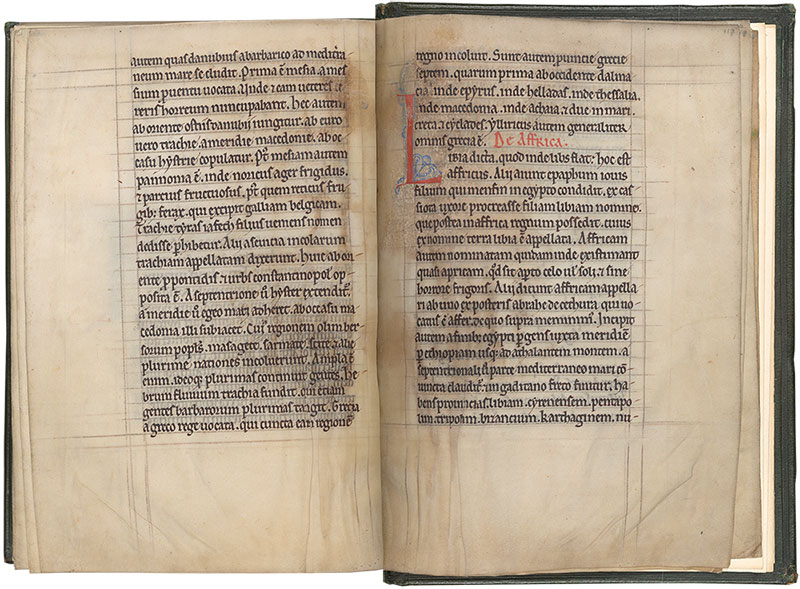

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 119v–120r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 120v–121r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

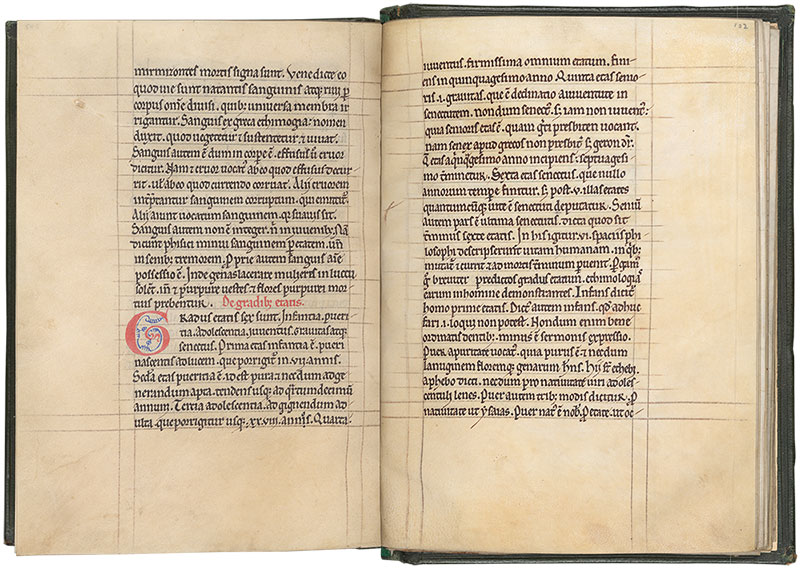

MS M.81, fols. 121v–122r

Worksop Bestiary

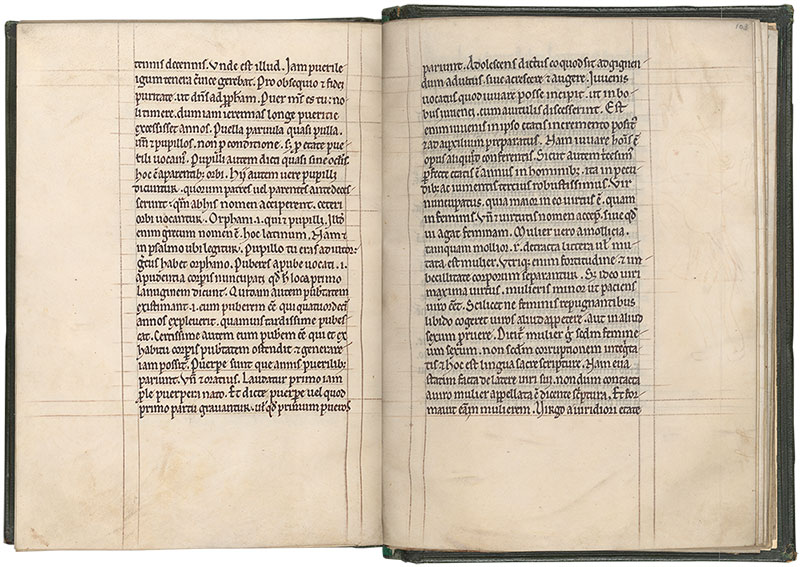

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, fols. 122v–123r

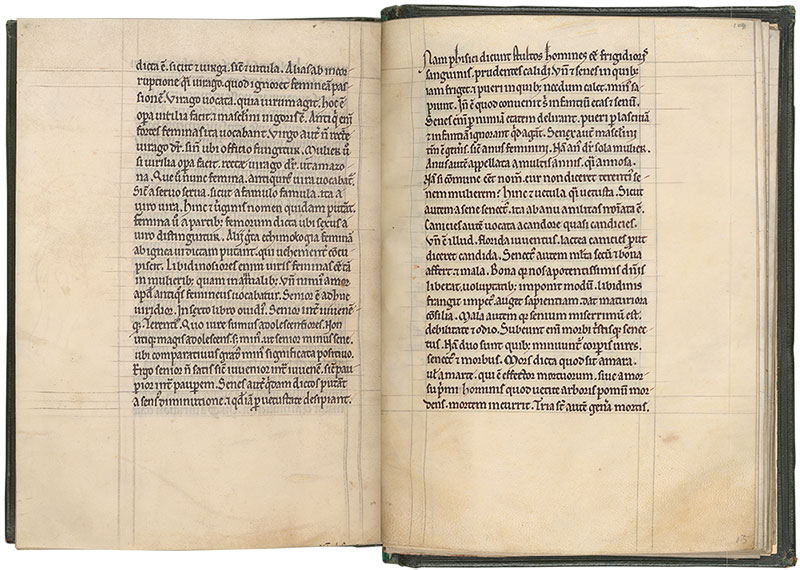

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

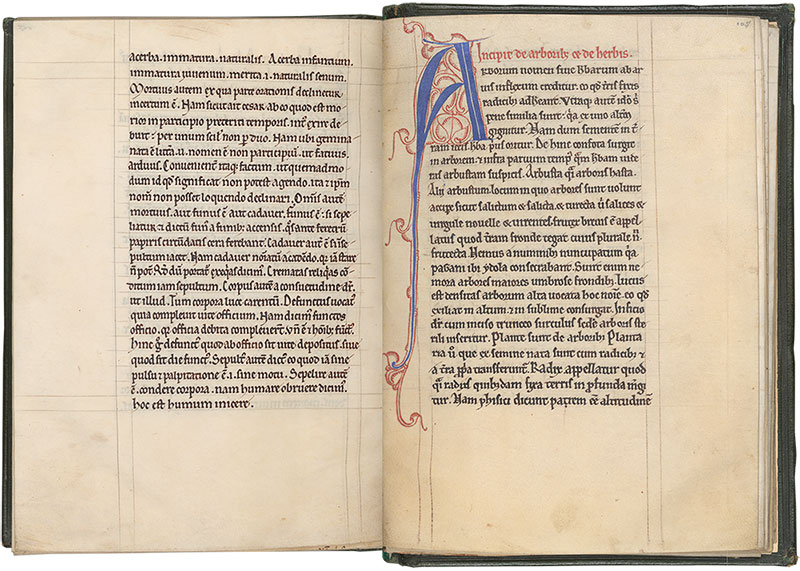

MS M.81, fols. 123v–124r

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902

MS M.81, back cover

Worksop Bestiary

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1902