Treasures of Islamic Manuscript Painting from the Morgan

Introduction

Although the Morgan is well known for its collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, it also holds important Islamic manuscripts full of extraordinary paintings. Since Islam refers to both the religious faith and civilization of Muslims, this online exhibition includes both religious and secular texts. Just as the Qur˒an is central to Islamic life, it is also the centerpiece of this presentation, followed by manuscript pages that illustrate works of science, biography, history, and poetry. Included are such important manuscripts as the Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals)—one of the finest surviving Persian examples—and the richest illustrated life of the beloved poet Rūmī (1207–1273). Also featured are pages from the Mughal and Persian albums that Pierpont Morgan acquired in 1911 from Sir Charles Hercules Read, Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum, and miniatures illustrating the work of great Persian poets.

To learn more about the art and culture of the Islamic world visit The Metropolitan Museum of Art's new Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia.

We are indebted to Barbara Schmitz for the research published in her invaluable 1997 catalogue Islamic and Indian Manuscript Paintings in the Pierpont Morgan Library, which also includes contributions by Pratapaditya Pal, Wheeler M. Thackston, and William M. Voelkle.

This online exhibition was created in association with the exhibition Treasures of Islamic Manuscript Painting from the Morgan, on view 21 October 2011 through 29 January 2012, organized by William Voelkle, curator and head of the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts. The exhibition is supported in part by a generous grant from the Hagop Kevorkian Fund and by the Janine Luke and Melvin R. Seiden Fund for Exhibitions and Publications.

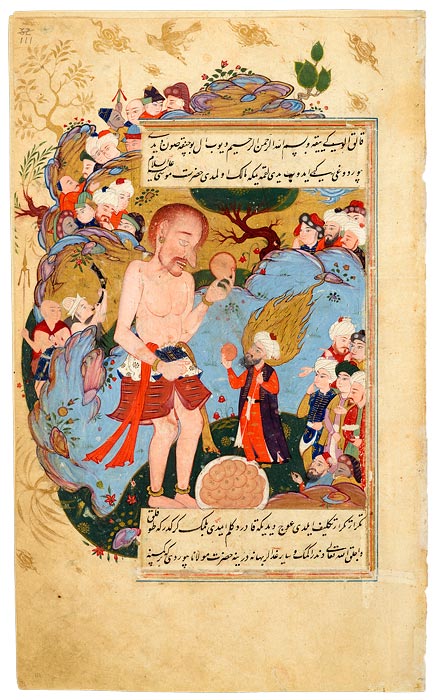

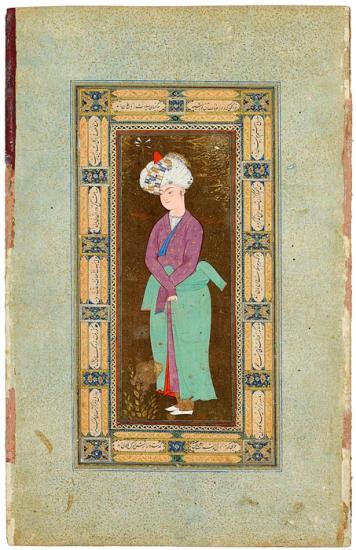

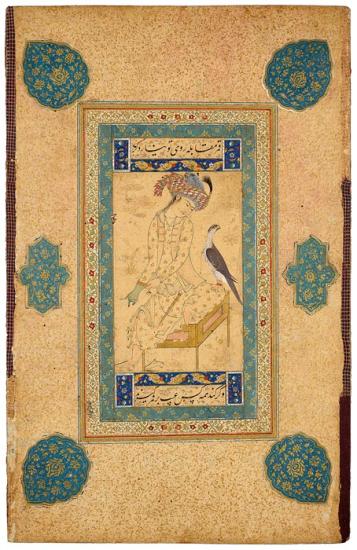

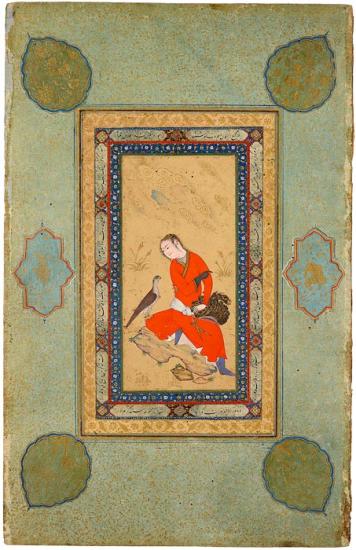

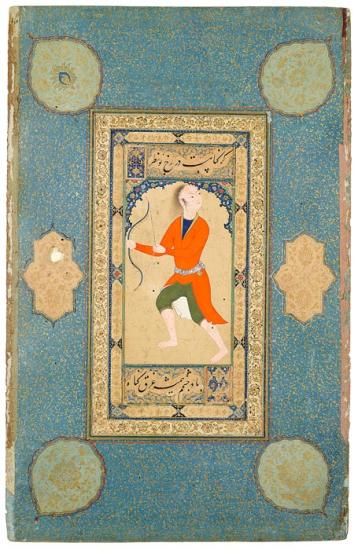

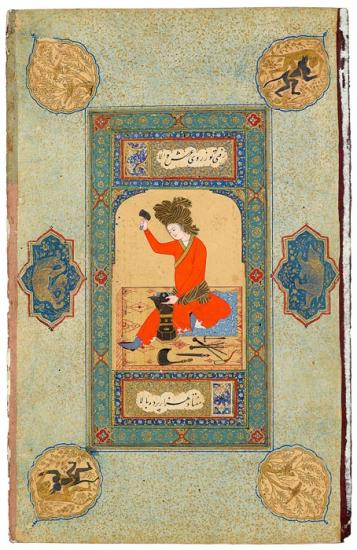

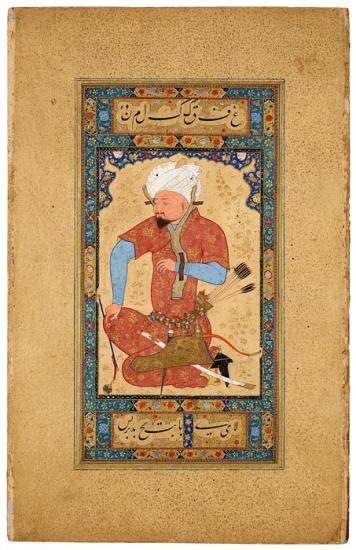

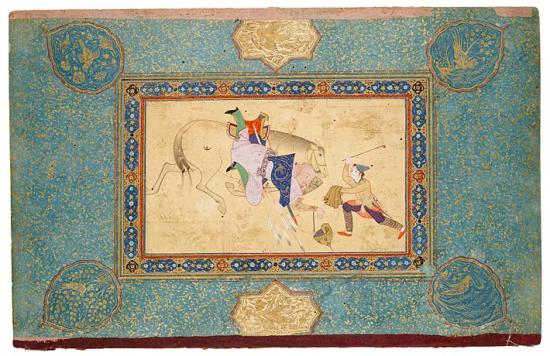

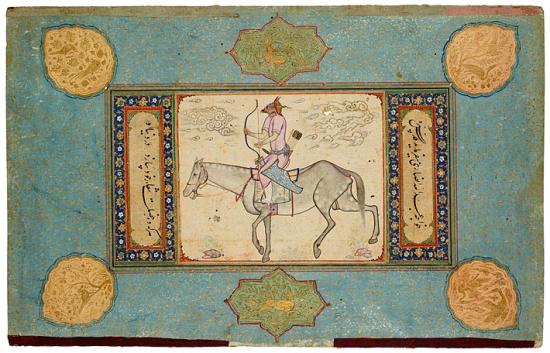

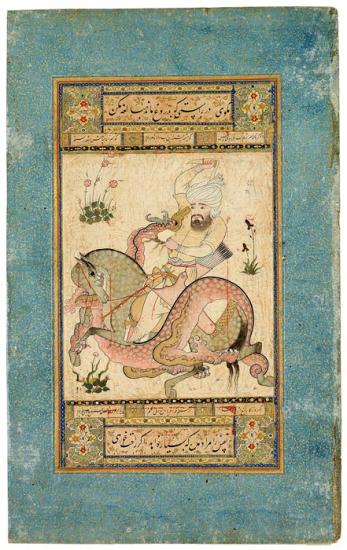

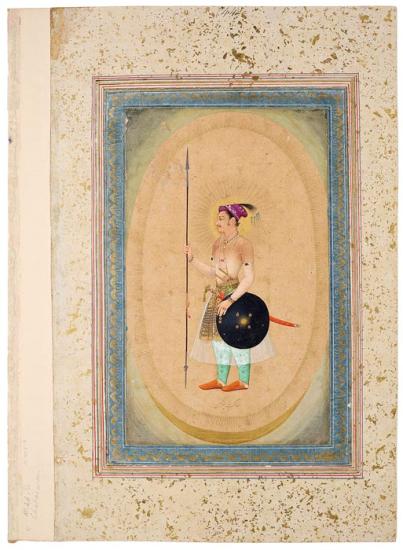

An Uzbek Prisoner

Leaf from the Read Persian Album. Probably Herat (Afghanistan), ca. 1600.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911.; MS M.386.2.

Overview

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

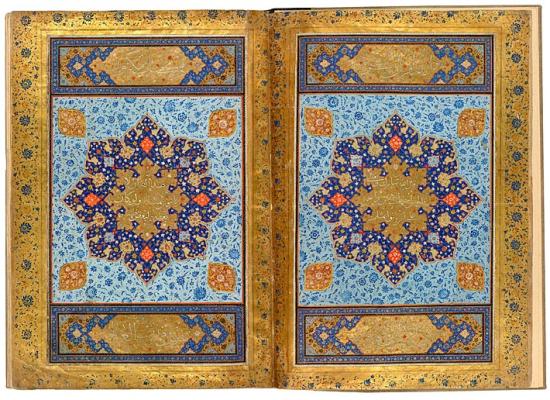

The Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an

Qur˒an, in Arabic.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, before 1913

This gigantic Qur˒an (19 x 13 1/2 inches) was made in Shiraz about 1580. In 1719–20 it was given by Sultan Aḥmad III to the mosque of Jerrāḥ Pasha in Dikili Tash in Istanbul. The opening pages express the majesty and magnificence of the Qur˒an. Within the facing sunbursts are inscribed the words from sura 17.88: God, blessed and exalted is he, said, say, if mankind and the jinn collaborated to produce the likes of this Qur˒an, they will not produce its like even if they assist one another. The jinn were pre-Adam angels cast down with Iblīs (Satan). Within the four cartouches are the words from sura 56.77–9: It is the noble Qur˒an, in a Book well guarded, which none shall touch but those who are clean.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

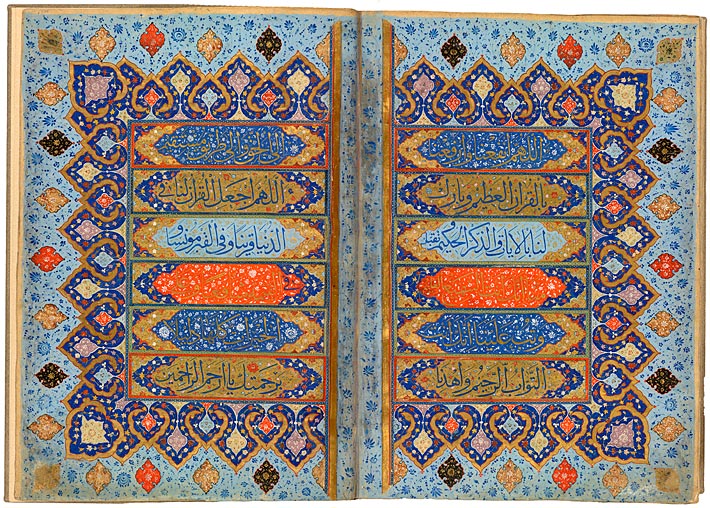

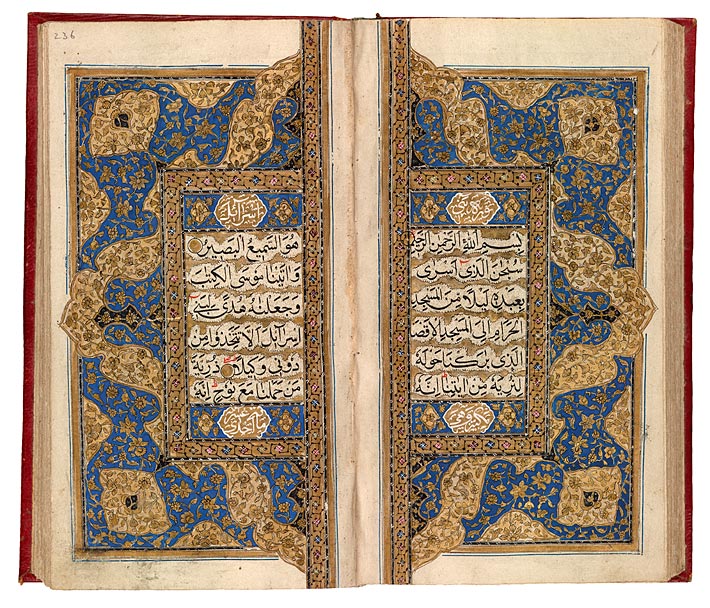

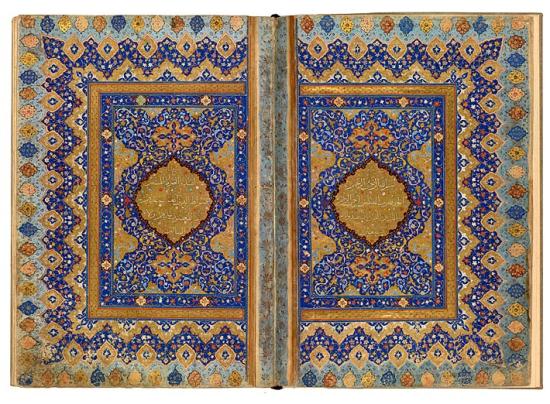

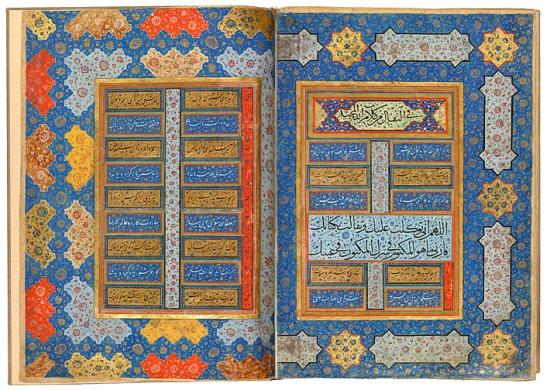

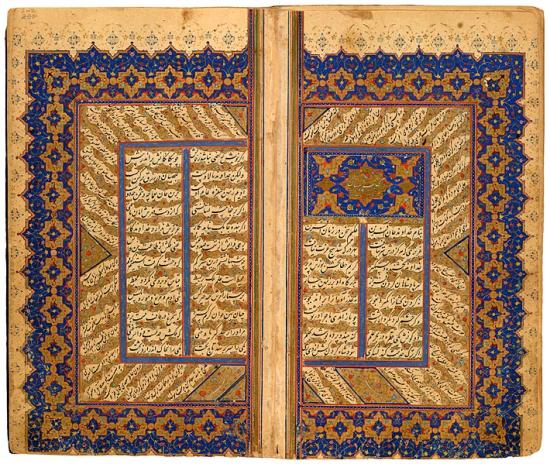

Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an fols. 2v–3r

The First Sura of the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, before 1913

This is the second pair of richly decorated facing pages in the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an, made in Shiraz about 1580. It marks the beginning of the Qur˒an itself, starting with sura 1 (al-Fātiḥa, or "The Opening Chapter"). The five lines of text on each page are enclosed within a gold-lobed medallion. They are written in raiḥān (sweet basil) script, which was much favored by poets, for its very name evoked its fragrance. Muḥammad Aṣlaḥ, an eighteenth-century poet, even wrote that real gardens would envy the raiḥān twig "lifting its head from the bismillah (call to piety)." The first line contains the title of the sura, followed by the call to piety, the bismillah: In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate. The sura is continued on the left page. Each sura (except the ninth) begins with the bismillah. This double-opening, and the three others in the manuscript, closely resemble the work of the Ottoman master gilder Muḥammad ibn Tāj al-Dīn Ḥaidar (d. 1588).

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

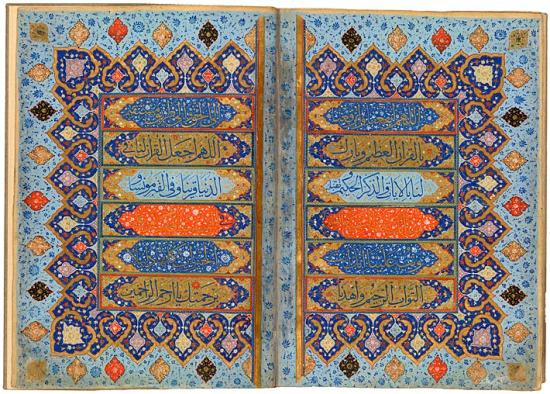

Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an fols. 274v–275r

Closing Prayer in the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, before 1913

This is the first of two pairs of elaborately ornamental facing pages that appear at the end of the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an, made in Shiraz about 1580. It enshrines a prayer written in twelve lines: Oh God, profit us and raise us through the magnificent Qur˒an, and bless us and accept the verses [we read] and the wise repetition [we make]... Turn toward us, for You are the Merciful One Who accepts the penitent, and guide us to the truth and to a straight path. Oh God, make for us the Qur˒an a constant companion in this world, a consoler to the grave, and... a guide for all good works, through Your mercy, oh Most Merciful.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an fols. 275v–276r

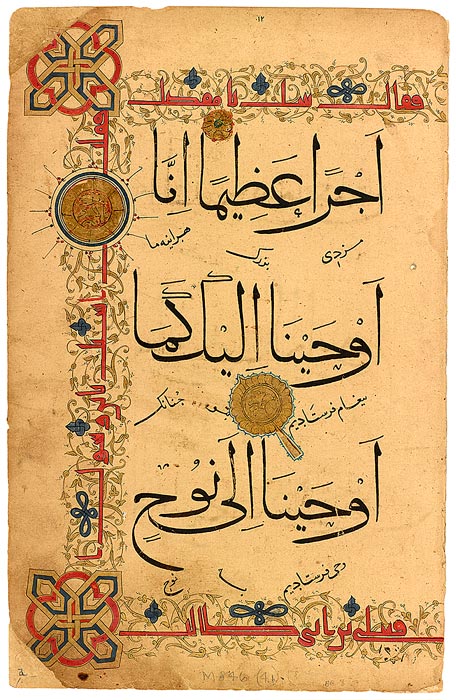

Auguries from the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, before 1913

The second pair of decorated facing pages at the end of the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an contains texts relating to the taking of auguries from the Qur˒an, with an interpretation for each letter of the alphabet. There is a break in the sequence, indicating a missing folio. The headings are in muḥaqqaq script and the lines of poetry are in nasta˓līq script. According to tradition, muḥaqqaq, meaning "accurate", or "well-organized," was the first script to be regularized.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an fol. 276v

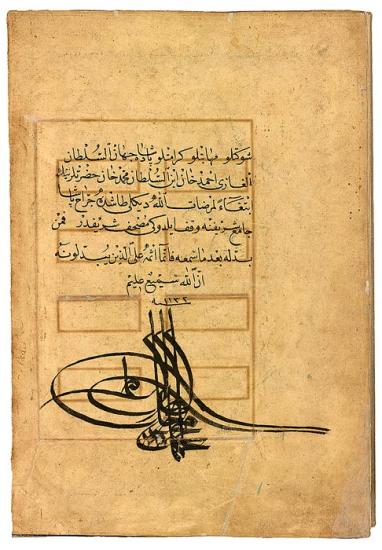

Presentation Page in the Jerrāḥ Pasha Qur˒an

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, before 1913

The last page of this Qur˒an contains a lengthy inscription stating that this copy was a pious gift to the holy mosque of Jerrāḥ Pasha in Dikili Tash in Istanbul in the time of "his exalted personage, the imperial, majestic, generous, padishah of the world, the victorious Sultan Aḥmad Khān, son of Sultan Muḥammad Khān, in the year of the Hijra 1131 (1719–20), may God be well pleased [with him]." Beneath the inscription is the magnificent tughra (official signature) of Aḥmad III.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Miniature Qur˒an and Banner Box

Miniature Qur˒an and Banner Box

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Bequest of Julia Wightman, 1994

Such miniature Qur˒ans are called sancak, after the standard-bearers (sancakdār) who attached them to military flags, where they served as talismans. Travelers also wore them as good-luck charms. This seventeenth-century octagonal example from Persia, which is about an inch and a half tall, is bound on one side and has sixteen lines of text per page. The silver banner box is nineteenth century.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

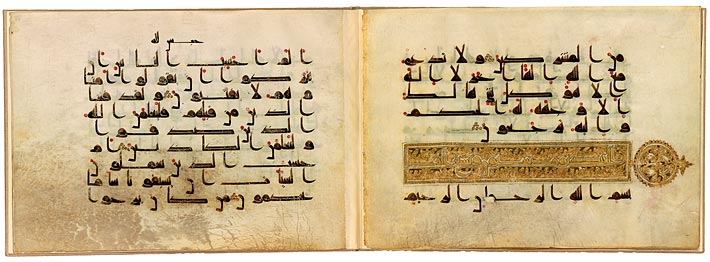

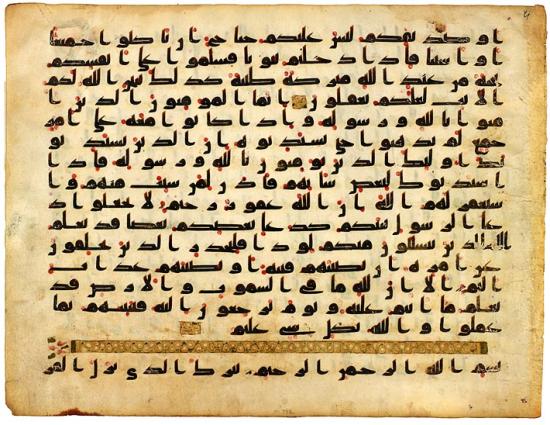

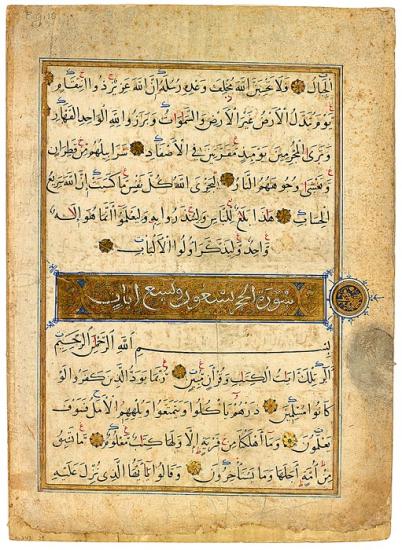

Early Tenth-Century Qur˒an

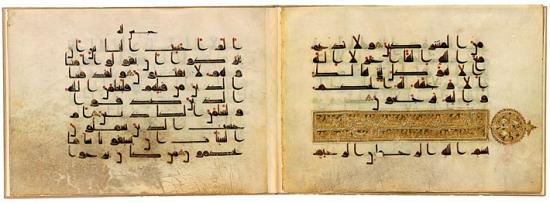

Fragment from an Early Tenth-Century Qur˒an

Qur˒an fragment, in Arabic

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1915

Although the earliest vellum Qur˒ans (late seventh to eighth centuries) were vertical in format, those of the ninth to eleventh centuries were oblong, perhaps inspired by the Kufic script, and featured oblong panels inscribed with Qur˒anic verses. Other folios from this manuscript are preserved in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul, and elsewhere, one stating that ˓Abd al-Mun˓im Ibn Aḥmad donated the Qur˒an to the Great Mosque of Damascus during July 911. The Morgan fragment contains suras 27 to 29. Shown here is the heading for sura 29 (al-˓Ankabūt, or "The Spider"), which is written in gold. The name is derived from those who, taking protectors other than Allah, are likened to spiders who build flimsy homes. The diacriticals consist of short diagonal lines, and red dots indicate vocalizations. Pyramids of six gold discs mark the ends of ayat (verses).

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

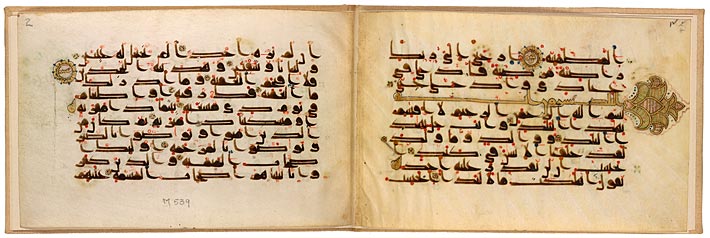

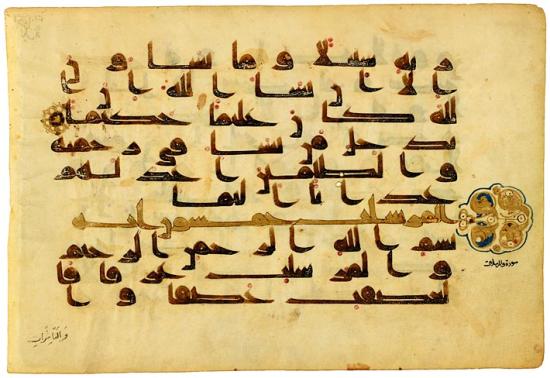

Tenth-Century Qur˒an

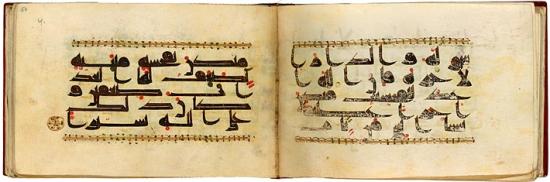

Fragment from a Tenth-Century Qur˒an

Qur˒an fragment, in Arabic

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, 1922

Qur˒ans could be in one or multiple volumes, sometimes as many as thirty, in which each volume contained a thirtieth of the text, called a juz˒. The division was especially popular because of the thirty-day holy month of Ramadan, when the entire Qur˒an could be read at the pace of a volume each day. The present fragment, however, was part of a smaller set, as two bands of illumination mark the end of juz˒ 21, which falls at sura 33.31 (al-Aḥzāb, or "The Confederates"). Voweling and diacritics are mostly in red. The gold rosette at the left marks the end of a tenth verse.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Tenth-Century Qur˒an

Folio from a Tenth-Century Qur˒an

Qur˒an leaf, in Arabic

Gift of Belle da Costa Greene, 1941

The text is written in Kufic, named after al-Kufah, the Iraqi town where the script supposedly originated. Red dots mark vowels, and each tenth verse is marked by a small, gold rectangle. On this leaf a thin gold band indicates the end of sura 24 (al-Nūr, or "Light") and the beginning of sura 25 (al-Furqān, or "The Criterion"). The Criterion is Allah's great gift to humanity, allowing it to judge between right and wrong. Each sura (except the ninth) begins with a call to piety, the bismillah, In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Tenth-Century Qur˒an

Page from an Oblong Tenth-Century Qur˒an

Qur˒an leaf, in Arabic

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

This is a typical vellum page from an oblong Qur˒an. The script is Kufic, and the red dots indicate vocalization. Every fifth verse is followed by a gold Arabic letter hā˒ (h, which has the numerical value of five; appears on the recto), and every tenth verse by a gold rosette. The heading to sura 77 (al-Mursalāt, or "Those Sent Forth") contains the first line of the sura in gold Kufic script and terminates in a palmette. The name of the sura is written, in cursive script, below the palmette.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Eleventh-Century Qur˒an

Two Folios from an Eleventh-Century Qur˒an

Qur˒an fragment, in Arabic

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1915

During Muḥammad's lifetime, Islam spread from Mecca and Medina, covering the entire Arabian Peninsula. From there, the new religion expanded throughout the Near East, northern Africa, and southern Spain. Other leaves from this Qur˒an are preserved in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, and in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. Written in Kufic, every fifth verse is followed by a gold letter hā˒ (which has a numerical value of five), and every tenth verse by a gold disc with the cumulative number of verses. The color scheme of the palmette projecting from the heading for sura 90 (al-Balad, or "The City"), a combination of wine red and green with gold and blue, is typical for the western Islamic world, suggesting an origin in northern Africa or southern Spain.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

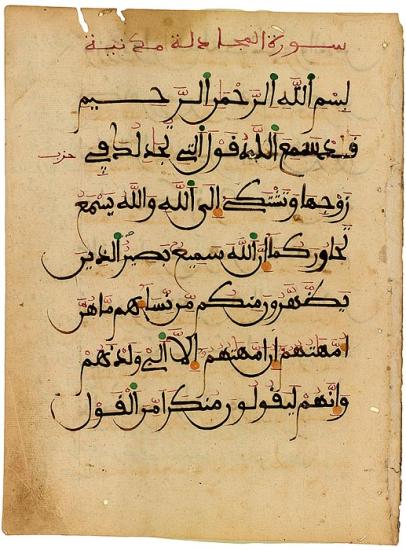

Maghribi Qur˒an

Folio from a Maghribi Qur˒an

Leaf from a Qur˒an, in Arabic

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Milton Freudenheim in memory of Otto F. Ege, 1985

Qur˒ans produced in the Maghrib (northwestern Africa and Spain) were written in a distinct script—Maghribi—named after the area where it was used. This example, from Morocco, is written in a dark brown ink. Voweling and the sura title are in mauve, yellow dots indicate diacriticals, and green dots appear only above initial alifs (a's). The text is the beginning of sura 58 (al-Mujādila, or "She Who Pleaded"). An early paper example, it is in a vertical format and dates from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

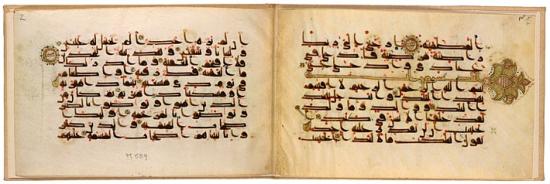

Mamluk Qur˒an

Bifolio from a Mamluk Qur˒an

Bifolio from a Qur˒an, in Arabic

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

With the increased use of paper and the adoption of more upright scripts, the oblong format of the early vellum Qur˒ans gave way to a vertical one. On this page a large heading in white, cursive script marks the beginning of sura 15 (al-Ḥijr, or "The Rocky Tract").The heading is followed by the usual bismillah (call to piety), and the sura text begins on the next line. The sura is in naskh script with vocalizations and diacriticals in black. There are reading marks in red and blue, and rosettes mark the ends of verses.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

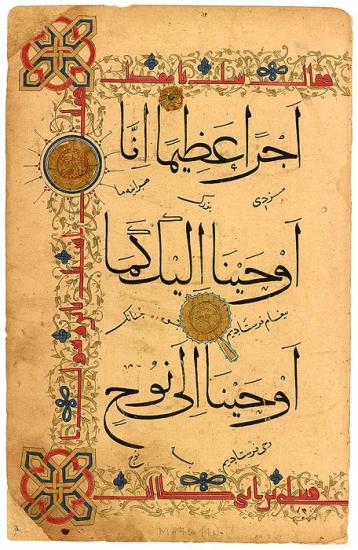

Qur˒an Leaf

Qur˒an Leaf with Interlinear Persian Translation

Qur˒an leaf, in Arabic and Persian

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

In this unusual leaf, verses 162–63 of sura 4 (al-Nisā˒, or "Woman") are written in a thuluth-muḥaqqaq script, while an interlinear Persian translation, in a small, cursive script, is written diagonally beneath the lines. Of special interest are the red Kufic inscriptions in the border, a Shi˓ite hadith (a saying of Muḥammad), which suggests the danger of independent Qur˒anic interpretation: A question was asked about the son of the Messenger [of God] and ˓Alī Ibn Abī ṭālib said, Woe unto you, O Qatāda, if you interpret the Qur˒an by yourself. The purpose of the central gold medallion is unknown. Other leaves from the manuscript are in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, and in the Freer Gallery, Washington, D.C.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

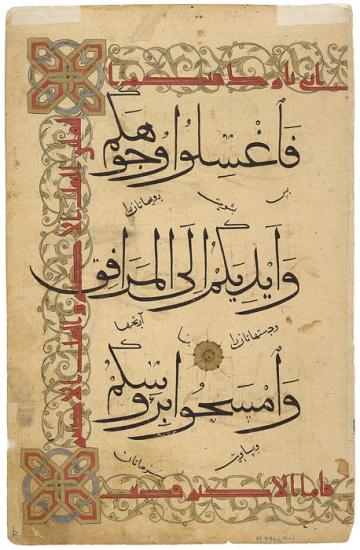

Washing Before Prayer

Washing Before Prayer

Qur˒an leaf, in Arabic and Persian

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

Although the Morgan has two leaves from this Qur˒an (see also MS M.846.4a), they are not consecutive, and thus their borders do not match. This page includes verse 6 of sura 5 (al-Mā˒ida, or "The Table"), urging the washing of faces, hands, and arms up to the elbow before praying. The silver Kufic inscription, a Shi˓ite hadith (a saying of Muḥammad), says that the words of ˓Alī and the succeeding imams have the same authority for Shi˓ites as those of the Prophet for Sunni Musliims: "I am going to leave you two valuables, the greater valuable and the lesser valuable. The greater is the book of my god, and the minor is my family and the people of my house [i.e., the twelve Shi˓ite imams]. If you preserve me through them you will never go astray so long as..."

(the text on this page breaks off here).

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

Qur˒an from Kashmir

Qur˒an from Kashmir

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Qur˒ans were written by hand well into the nineteenth century, and many copies were produced about 1800, when Kashmir was still under Muslim rule. They differ from contemporary Turkish Qur˒ans, which usually provide a date and name of the scribe. The type of decoration found on this double-page sarlauḥ represents typical Kashmiri work of about 1800. This Qur˒an has been divided into sevenths (manzil), one to be read each day of the week, much like the Psalter. Here the double-page sarlauḥ marks the beginning of the fourth division, suras 17 (Bani Isrā-il or "The Israelites") to 25 (al-Furqān or "The Criterion"). The script is naskh, the sura headings are in white, and gold dots follow verses.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

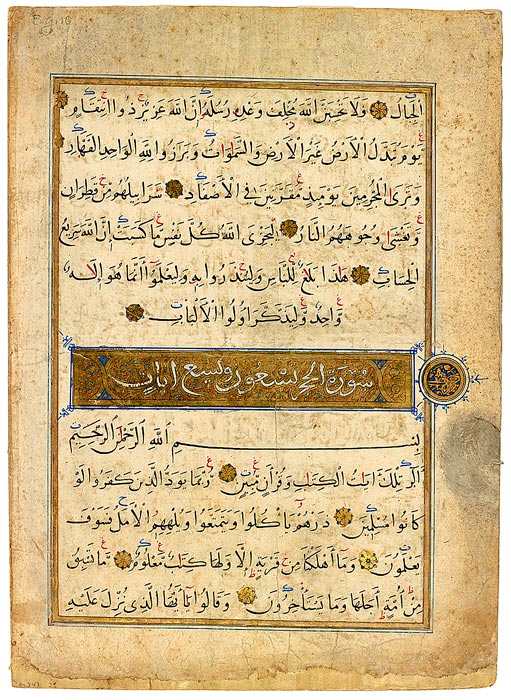

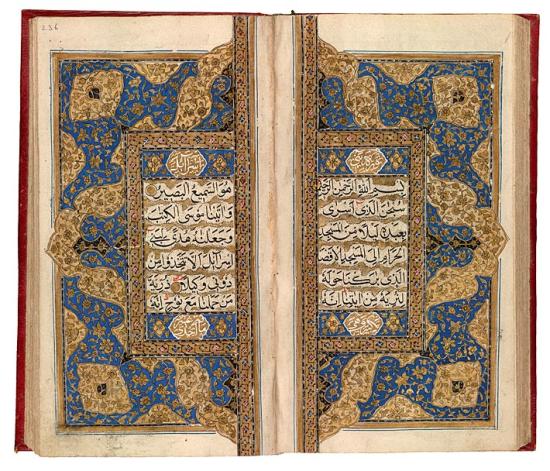

Turkish Qur˒an

Turkish Qur˒an by Pashāzāde

Qur˒an, in Arabic

Purchased by Morgan before 1913; bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

Unlike late Kashmiri Qur˒ans, those made in Turkey are often fully documented, providing not only a date but the name of the scribe and often that of his teacher. According to the colophon, the manuscript was written in 1832–33 by ˓Alī al-Rusdī al-Asbārtavī, known as Pashāzāde, a student of al-Ḥājj Ḥāfīz Mustafa Ḥelvī, known as Helvajizāde. This sarlauḥ marks the opening of the Qur˒an, with sura 1 (al-Fātiḥa, or "The Opening.") on the right, and sura 2 (al-Baqarah, or "The Heifer") on the left. The text is written in naskh script, and the end of each verse is marked by a rosette. Sura headings, in the cartouches, are written in a white, cursive script.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

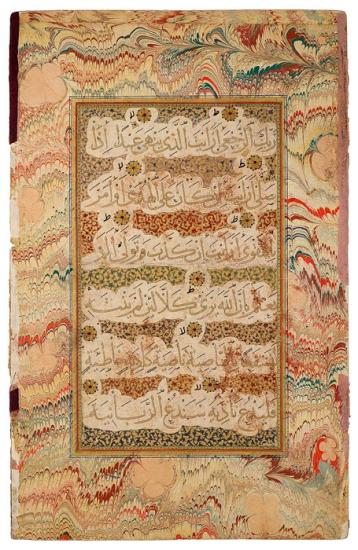

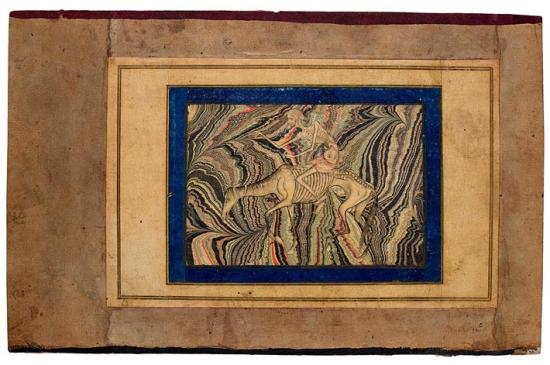

Persian Qur˒anic Leaf

Qur˒anic Leaf from the Read Persian Album

From the Read Persian Album

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Sometimes beautifully written and framed Qur˒anic passages were preserved in albums. This magnificent leaf originally must have faced a page that began with Muḥammad's first revelation (610), sura 96.1—5 (Iqraa, or "Read!" or "Proclaim"), also known as al-˓Alaq ("The Clot of Congealed Blood"), as the present leaf contains verses 8–18. The names come from the verses: Read! (or Proclaim) in the name of your Lord and Cherisher, Who created—created man, out of a [mere] clot of congealed blood. . . .Proclaim . . . He Who taught [the use] of the pen. The six lines of muḥaqqaq script contain ten short ayat (verses), each ending with a gold rosette. Marbling (abri, or "clouds," in Persian) was known in Persia by the sixteenth century, when named abri masters are documented.

The Qur˒an, the Holy Book of Islam

From a monumental volume used in an Istanbul mosque to a miniature Persian version that served as a talisman, this section features examples of illuminated pages from the holy book of Islam. The Qur˒an (to recite) represents the codification of the words of God that were revealed and transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632) over a period of twenty-three years. The visions began in 610 in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca, his birthplace, and continued after his 622 flight to Medina, until his death. His flight—the Hijra—marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

The revelations were arranged into 114 suras (chapters), each named after its theme. The first and shortest ones, at the end of the book, from the Meccan period, establish Muḥammad as the final prophet in a line of monotheists, including Abraham and Jesus. The longest suras, placed at the beginning, are Medinan and deal more with social and political issues.

For centuries, Qur˒ans were written in Arabic, the language of transmission. After Muḥammad's death, his cousin ˓Alī and others compiled the revelations into a text. About twenty years later, under Uthman, the third caliph (644–656) succeeding Muḥammad, a standard version of the Qur˒an —essentially the one used today—was produced. Thereafter Islam (which means "surrender to God") spread from the Arabian Peninsula throughout the Middle East, to northern Africa and southern Spain, and eventually the world.

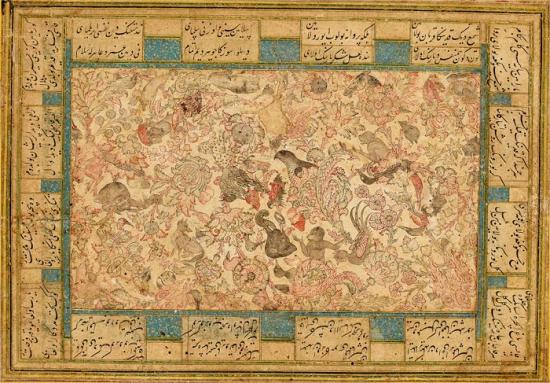

Natural History and Astrology

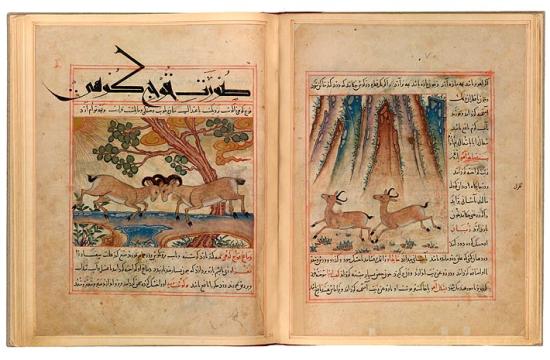

Two Gazelles and Two Mountain Rams

Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals), in Persian, for Shams al-Dīn Ibn Ẓiyā˒ al-Dīn al-Zūshkī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912

Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals) ranked among the ten greatest Persian manuscripts, dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book. The Mongol invasion, culminating in the conquest of Baghdad, brought a new, Chinese naturalist style to Persian art. The text discusses the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. On the right, two gazelles run in front of a steep, rocky mountainside, kicking up dust (derived from a misunderstood misty landscape model), while on the left two mountain rams fight on a fanciful Chinese-style bridge composed of colored rocks, with gold clouds in the sky.

The manuscript was made at Maragha (south of Tabriz), a center of learning. It was there that Hulagu Khan (r. 1217-1265) built the famous observatory for Nasīr al-Dīn al-Ṭusī, the famous schlar and astronomer.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

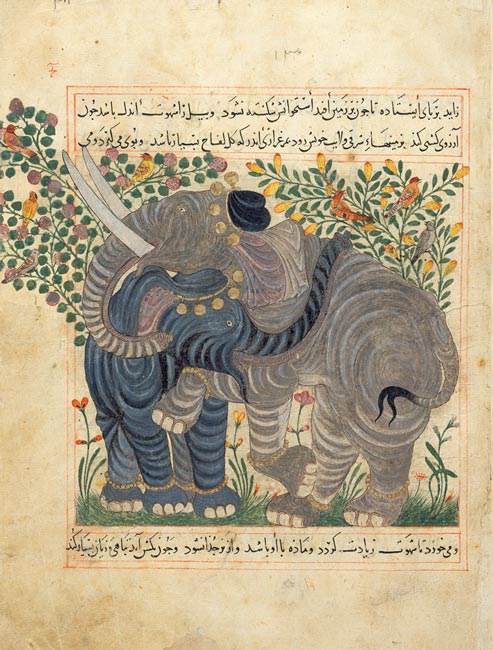

Two Elephants

Two Elephants

Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals), in Persian, for Shams al-Dīn Ibn Ẓiyā˒ al-Dīn al-Zūshkī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912

The two interlocking and rather affectionate elephants shown here make up one of the finest of the forty-four large illustrations in the manuscript Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals). They are royal elephants, as seen from their caps and the bells on their feet. The text describes both the habits and medicinal derivatives of the animal. Among the former, for example, it is stated that the tongue of the elephant is upside down, for if it were not, it could speak, and that the elephant was called "barrus on account of its voice, whence the voice is called baritone." Among the latter—and these have not been tested by the Morgan—are suggestions that elephant broth is good for colds and asthma, that elephant dung (taken with or without honey) prevents conception, and that one dram of ivory filings will bring about conception.

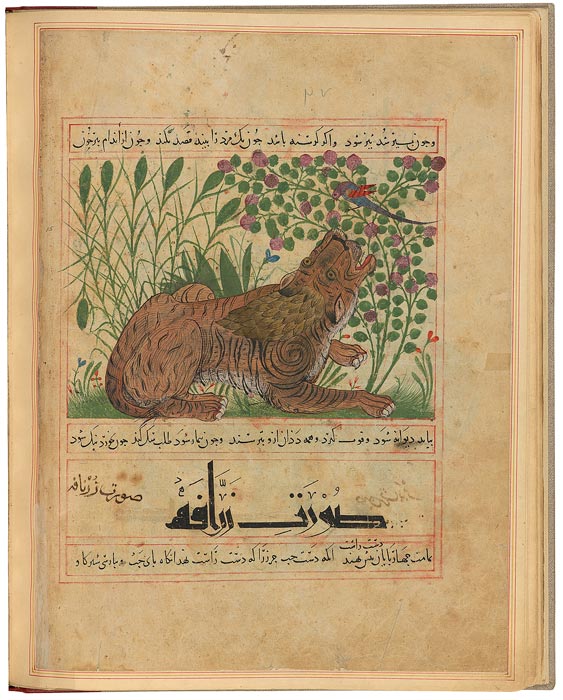

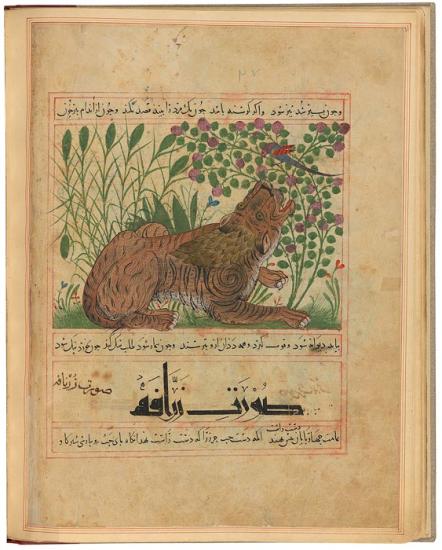

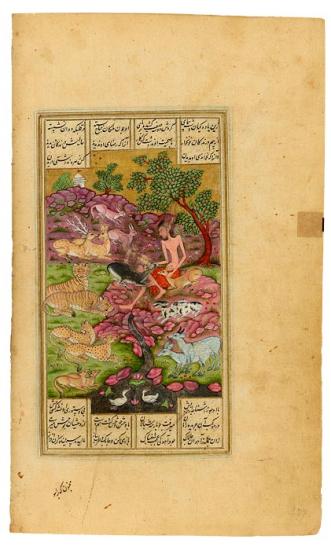

Tiger

Tiger

Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals), in Persian, for Shams al-Dīn Ibn Ẓiyā˒ al-Dīn al-Zūshkī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912

This illustration appears in the great Persian manuscript Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals). The recumbent lion raises its head, appearing to converse with the bird in the flowering bush above. The text mentions no medical derivatives of the tiger. Under the reeds are traces of a sketch, in red, of a camel facing left, indicating that the paper was reused.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

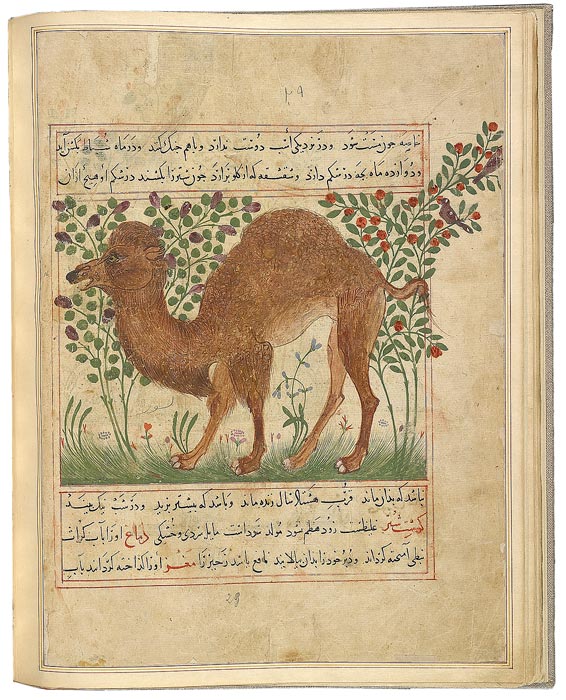

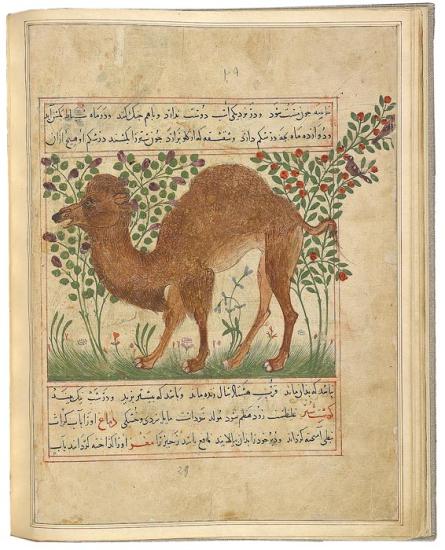

Camel

Camel

Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals), in Persian, for Shams al-Dīn Ibn Ẓiyā˒ al-Dīn al-Zūshkī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1912

This illustration appears in the great Persian manuscript Manāfi˓-i ḥayavān (The Benefits of Animals). The camel's forelegs are too short, suggesting that the artist's model was too large to fit the available space, and its head has a strange pompadour of hair, perhaps to compensate for the short legs. According to the text the camel is revengeful and thus has a good memory. They conceive in February, have a twelve-month gestation period, and hate the company of horses, as they always fight. Different parts of the camel were used medicinally. Its hump, for example, is good for dysentary; melted and mixed with chive juice it relieves the pain caused by piles.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

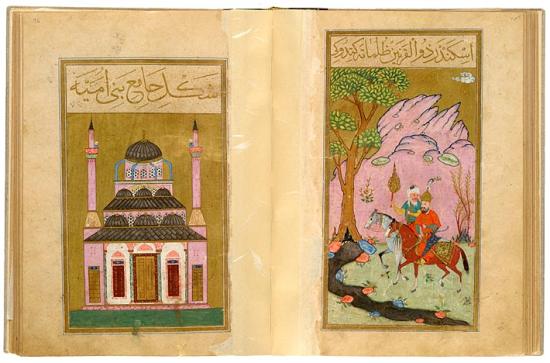

Iskandar and Khiżr

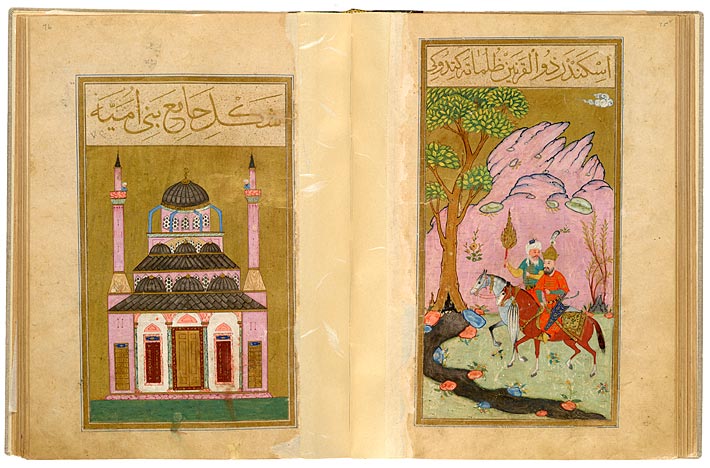

Iskandar and Khiżr Seek the Water of Eternal Life and the Mosque of the Bani Umayya

Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), in Turkish

Illuminated by Vali Jan for ˓Āyisha Sulṭān (d.1604), the daughter of Sultan Murād III

Purchased in 1935

This book, made for ˓Āyisha Sulṭān (the daughter of Sultān Murad III), , contains texts relating to astrology, wonders of the world, talismans, and divination. These two miniatures illustrate the second section. Here Iskandar (Alexander the Great) and Khiżr (the green one) enter the Land of Darkness in search of the Fountain of Life. Khiżr, holding a torch, glances at Iskandar. Although the mosque on the left is identified as the ancient mosque of the Umayyads (ca. 650–751) in Damascus, the artist depicted a typical sixteenth-century Ottoman mosque. A twin manuscript painted by ˓Osmān in Paris (BnF, Suppl. turc 242) was made for Fāṭima Sulṭān, another daughter of the Ottoman ruler/bibliophile Murād III (r. 1574–1595) who commissioned the translation.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

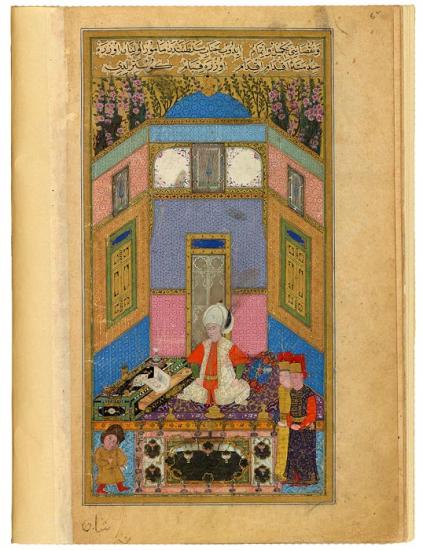

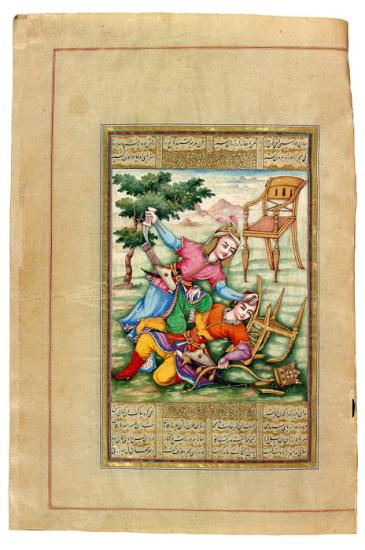

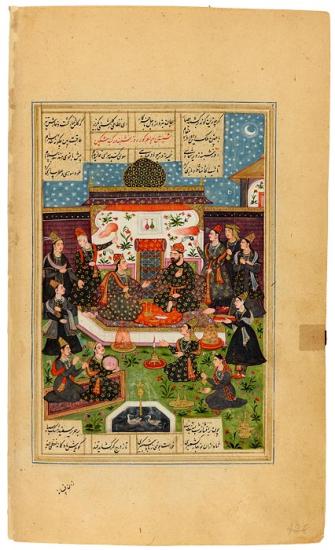

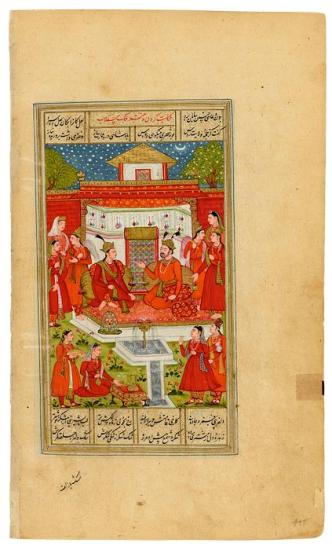

Sultan MurĀd III

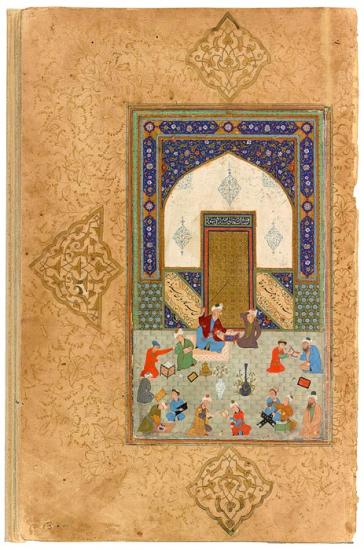

Sultan MurĀd III in his Library

Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), in Turkish

Illuminated by Vali Jan for ˓Āyisha Sulṭān (d.1604), the daughter of Sultan Murād III

Purchased in 1935

Murād III (r. 1574–95), the son of Selim II (r, 1566–74) and grandson of Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66), ushered in a golden age of Ottoman painting, commissioning illustrated manuscripts of historical, literary, and scientific texts, many made in Istanbul's imperial scriptorium. He also ordered that texts be translated into Turkish.

Here Murād III actually admires the very manuscript for which this is the opening miniature—-the Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda, made for his daughter ˓Āyisha Sulṭān.; He is examining the section of the manuscript depicting zodiacal signs and the three planets associated with their decades. The face of the sultan, alas, has been altered, perhaps by a later owner, as he should have been depicted with a beard, as he is in the closely related miniature in Paris. The book is supported by the open drawer of a luxurious portable desk of ebony and ivory, on top of which are various implements, including an hourglass and a western clock. Murād is attended by two janisarries wearing their elite and distinctive headgear, and a dwarf.

Murād was interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism and ordered a Turkish translation (1590) of Aflākī's life of Rūmī, Persia's greatest poet and mystic. Murād wrote poetry, and in 1584 built the kitchen and dervish cells of the Mevlevī convent in Konya, where he had gone with Selim during the siege of 1559 (see MS M.466, fol. 131r). As sultan, Murād never left Istanbul but took full advantage of the imperial harem. By the time of his death at age forty-nine he had fathered one hundred and two children and left seven pregnant concubines; sixty-two died during his lifetime, and nineteen sons were murdered by Mehmed III when he ascended the throne.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

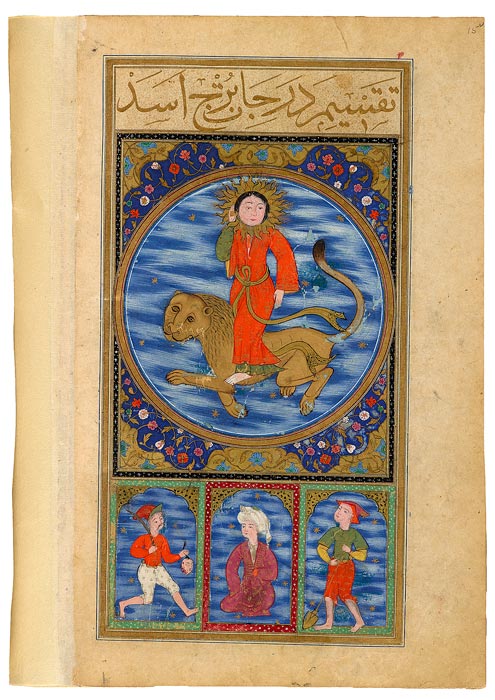

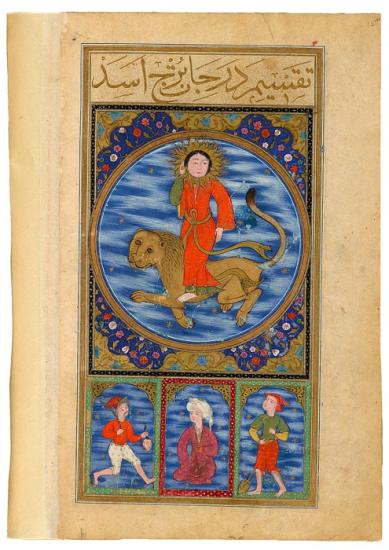

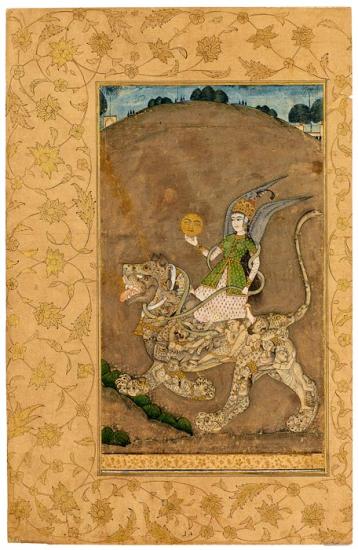

Leo Ridden by a Personification of the Sun

Leo Ridden by a Personification of the Sun

Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), in Turkish

Illuminated by Vali Jan for ˓Āyisha Sulṭān (d.1604), the daughter of Sultan Murād III

Purchased in 1935

This astrological illustration is one of twelve in the manuscript that depict the zodiacal signs and the three planets associated with their decades. Leo, the lion, ridden by a personification of the sun, is depicted within the roundel. The lords of the decades are shown in the arcades below: Saturn using a spade, Jupiter holding a book, and Mars holding a mace and severed head.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

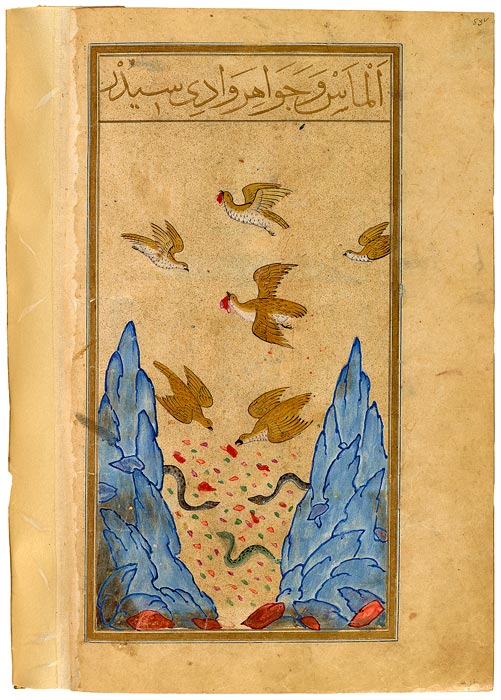

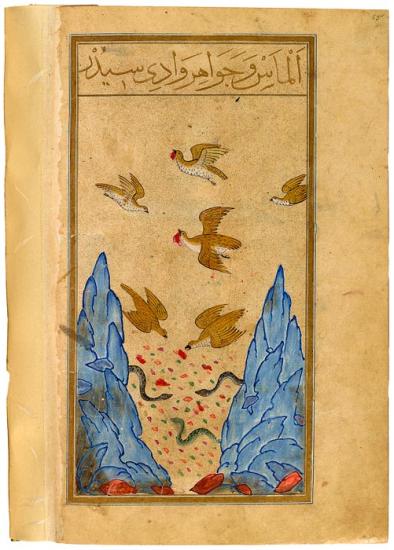

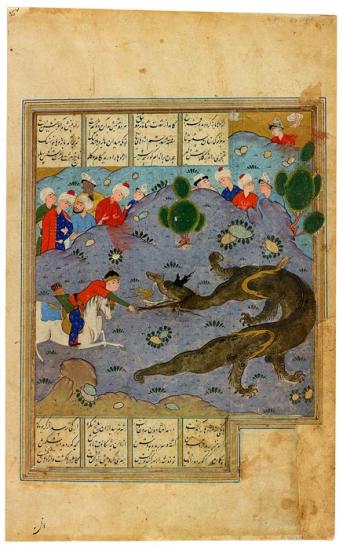

The Valley of Diamonds and Jewels

The Valley of Diamonds and Jewels

Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), in Turkish

Illuminated by Vali Jan for ˓Āyisha Sulṭān (d.1604), the daughter of Sultan Murād III

Purchased in 1935

In this illustration from a sixteenth-century Turkish manuscript commissioned by Sultan Murād III, the deep rocky valley was filled with diamonds and jewels, and Iskandar (Alexander the Great) was asked how they could be safely obtained, as they were protected by terrible creatures, here represented as poisonous snakes. His solution was to throw raw meat into the valley, to which the gems would stick. The birds would then swoop down into the valley, carry off the gem-laden meat in their talons, and take it to the top, planning to eat the meat there. The birds would then be scared away, and the gems separated from the meat.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

Sleeping Man

A Sleeping Man is Oppressed by a Nightmare

Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), in Turkish

Illuminated by Vali Jan for ˓Āyisha Sulṭān (d.1604), the daughter of Sultan Murād III

Purchased in 1935

According to the title above the painting, this jinn (a pre-Adam angel cast down with Iblīs, or Satan) is called Kabus, which can literally be translated as Nightmare. Jinns are invisible and were created by God, but are half-men and half-animals, and can behave well or badly. They can inflict illness and other ailments, so deserve protective talismans (the gold emblems). Here Kabus, wearing trousers and gold anklets, and accompanied by two horned attendants, swoops down on the man, hoping to ruin his sleep. This illustration appears in a sixteenth-century Turkish manuscript commissioned by Sultan Murād III.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

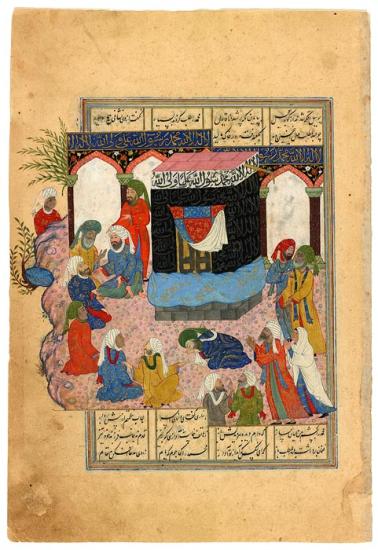

ʻAbd al-Muṭṭalib

ʻAbd al-Muṭṭalib, Grandfather of the Prophet Muḥammad, Kneels Before the Kabba in Mecca

Leaf from the Chester Beatty Āsār al-muẓaffar (A Life of Muḥammad)

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

The Kaaba (The Cube), the most sacred site in Islam, was, according to the Qur˒an, built by the prophet Abraham and Ismael, his son. Regardless of their location, Muslims always face the Kaaba during prayer. Since Muḥammad's father died nearly six months before his birth, he was brought up for two years with his paternal grandfather, ˓Abd al-Muṭṭalib, who died when Muḥammad was eight. His uncle, Abū ṭālib, custodian of the Kaaba, then looked after him. Here the Kaaba is covered with a black cloth (kiswa) decorated with the shahada (declaration of faith: There is no god but Allah, Muḥammad is the messenger of Allah) and ˓Alī is the friend of God. Before Muḥammad, there were 360 idols in the Kaaba. In another miniature in the Chester Beatty manuscript, he orders their destruction. The style of miniature, the circular composition, and the subject matter anticipate the Baghdad school of painting that flourished from about 1585 to 1605, and of which the Morgan life of Rūmī (MS M. 466) is a masterpiece.

Natural History and Astrology

The miniatures presented here derive primarily from two extraordinary Islamic manuscripts that depict the natural world and the heavens. The first, Manāfi˓-i hayavān (The Benefits of Animals), is considered one of the ten greatest surviving Persian manuscripts. It dates from the reign of Ghazan Khan (1295–1304), the Mongol ruler who ordered a Persian translation of the book, and concerns the nature and medicinal properties of humans, animals, birds, reptiles, fish, and insects. The other, Matāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda (The Ascension of Propitious Stars and Sources of Sovereign), was commissioned by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95), an Ottoman ruler deeply interested in astronomy, cosmology, demonology, poetry, and mysticism.

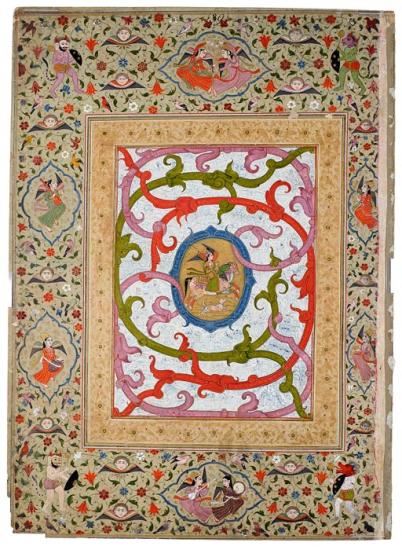

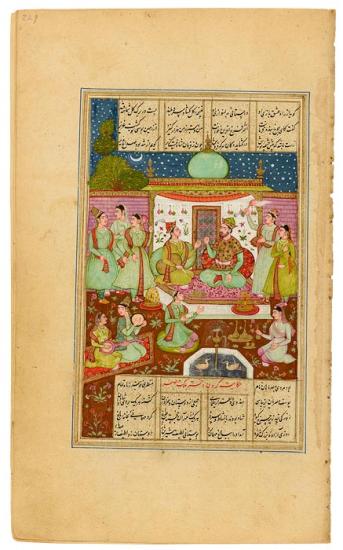

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

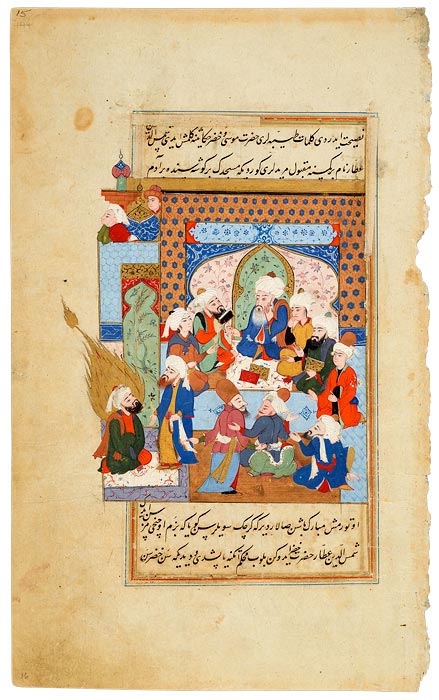

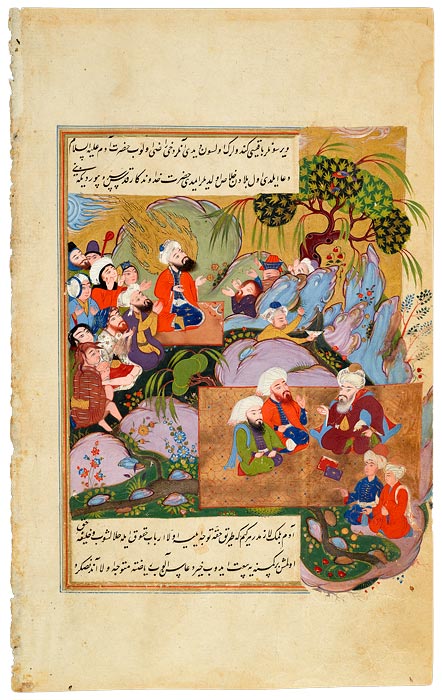

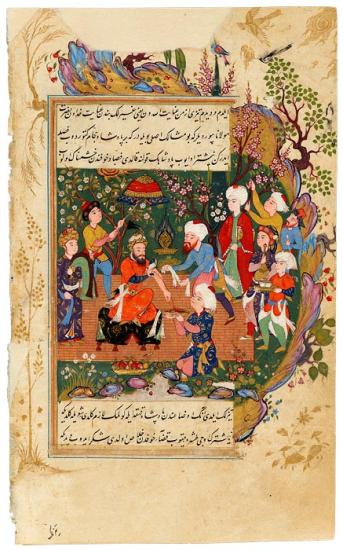

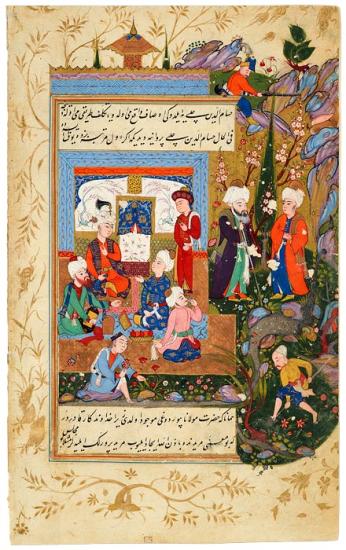

Rūmī's Father Gives a Sermon in the Qāni˓ī Cemetery of Konya

Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (A Translation of Stars of the Legend), in Turkish

The translation was ordered in 1590 by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95) from the Persian abridgement of Aflākī.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Rūmī's father, Bahā˒ al-Dīn (d. 1231), a revered scholar and a man of great sanctity, reportedly worked many miracles in Konya. Seljuk Sultan ˓Āla˒ al-Dīn Kaiqubād I (r. 1219–1237) once ordered him to give a sermon in Konya's cemetery that proved to be so moving that the dead came out of their graves. At another point, shown here, pairs of hands emerge from the graves, their owners proclaiming, "Amen." The incident is not included in the original Persian text; it was added by the Turkish translator. Bahā˒ al-Dīn, dressed in green, sits on a tall gold chair; in the front is a dark-skinned dervish with burn marks (showing ardor for the beloved) and two men, seen from the back, embracing. Some figures wear the distinctive tall, honey-colored, felt hats of the Mevlevī order.

This miniature is part of a sixteenth-century manuscript account of the life and miracles of the Persian poet and mystic known as Rūmī. It is a Turkish translation of an abridged version of the original fourteenth-century Persian account by the dervish known as Aflākī.

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

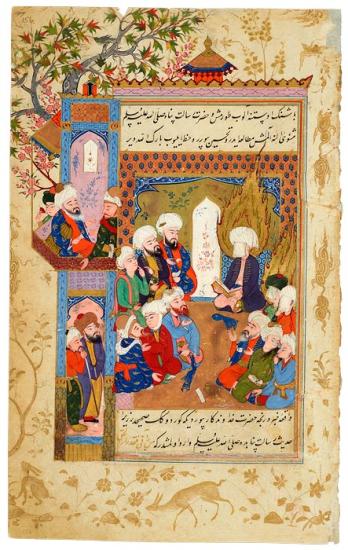

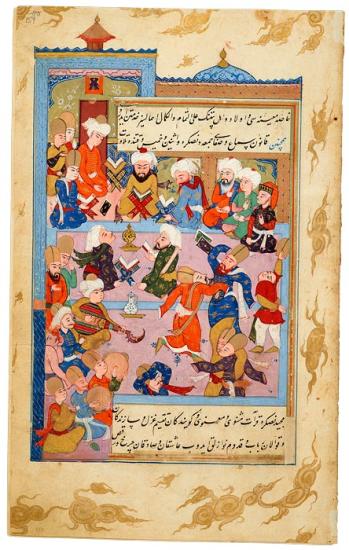

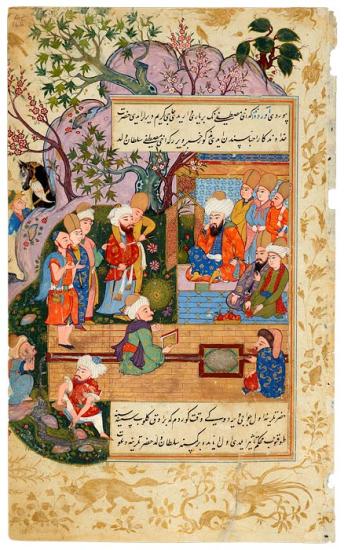

The sixteenth-century miniatures presented here concern the life and miracles of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, called Mē vlāna (Our Master), the most famous member of the Mevlevī order and Persia's greatest Sufi mystic and poet. He was born in Balkh in 1207, but his family emigrated after his father foresaw the Mongol conquest. They eventually resettled in Konya, Turkey, then the capital of Anatolian Rūm (thus Rūmī), where the poet died on 17 December 1273.

Several Persian accounts of Rūmī's life have been written, the first by his son, Sultan Walad. The third, laden with moralizing miracle stories, was ordered by Rūmī's grandson Ulu ˓Ārif Chelebi. It was written by the dervish Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad, called Aflākī (d. 1360). Aflākī also incorporated verses from Rūmī's works, notably his six-volume Masnavī (a poetical form of rhyming couplets) and the Dīvān-i-Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, named after Shams of Tabriz, the mystic who changed Rūmī's life and transformed him into a poet when they met in 1244.

In 1590—three and a half centuries after Aflākī wrote his life of Rūmī—the Ottoman sultan Mūrad III ordered a Turkish translation of a 1540 abridged version of Aflākī's text entitled Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (Stars of the Legend). The translator was Darvīsh Mahmud Mesnevī Khān of Konya. Two illustrated copies of the Murād translation, both made in Baghdad, survive. One, dated 1599, is held by Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and has twenty-two miniatures. The other, richer manuscript is held by the Morgan. It dates to the 1590s and includes twenty-nine miniatures. They are all featured here, along with two folios from other collections that are believed to have once been part of the Morgan manuscript.

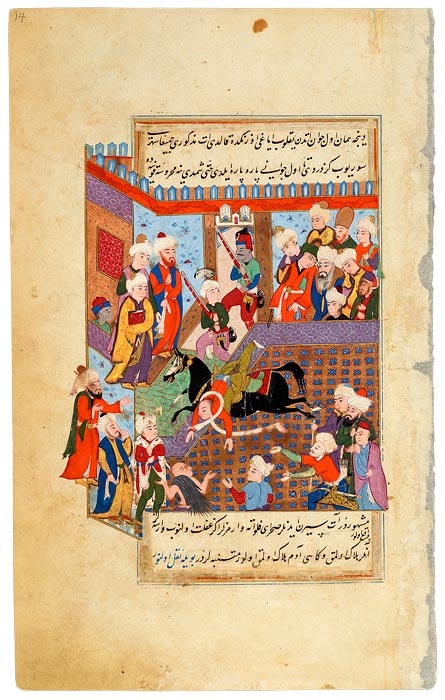

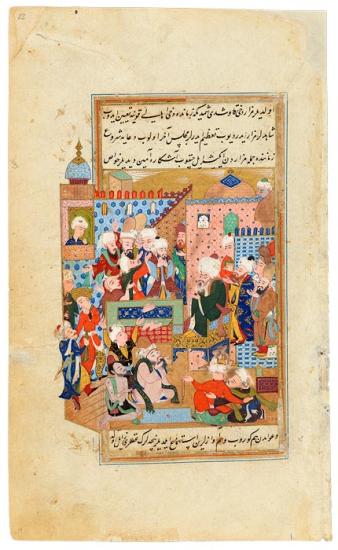

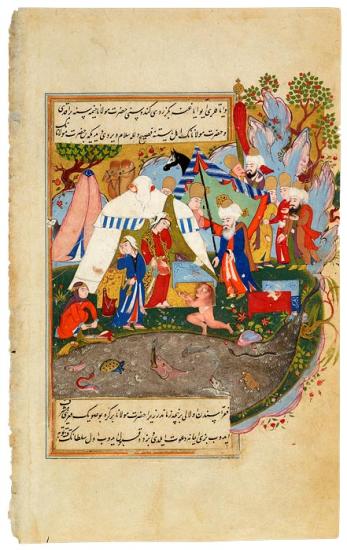

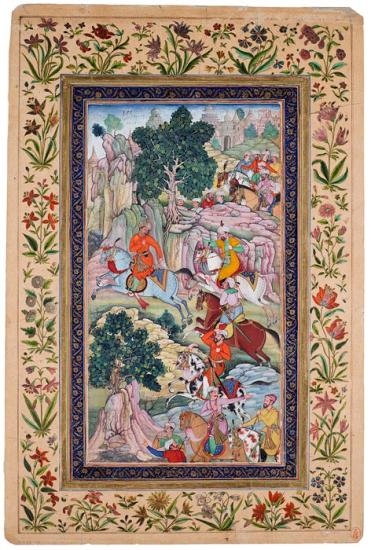

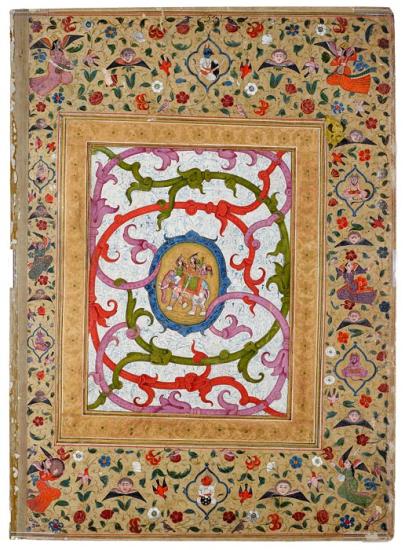

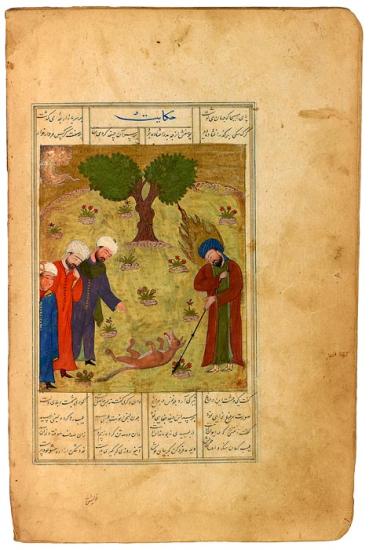

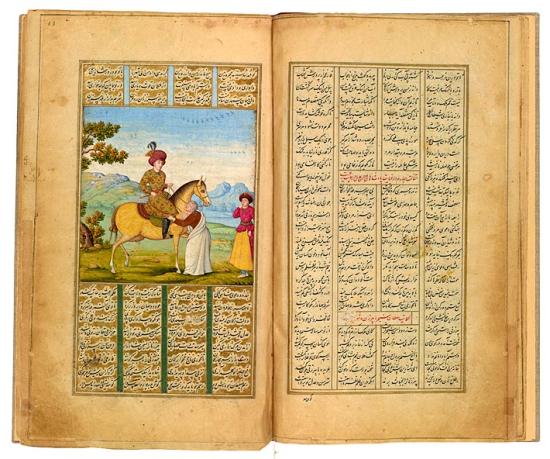

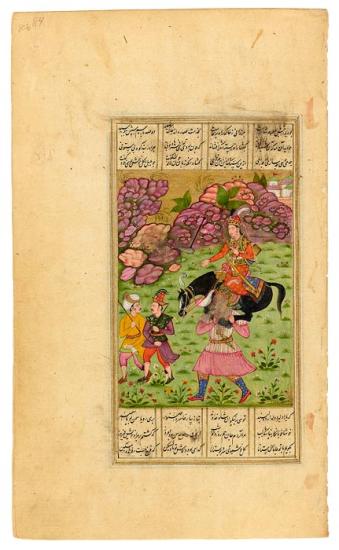

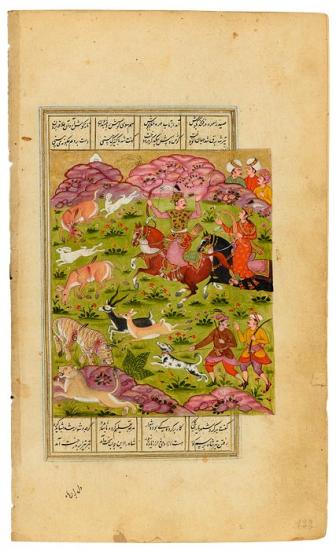

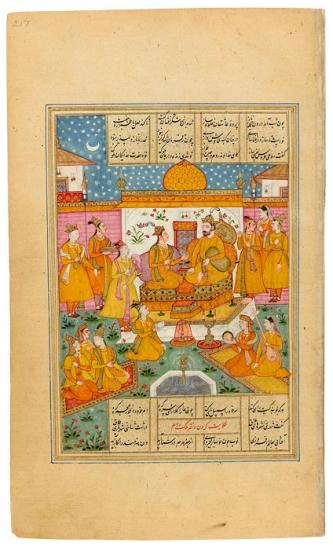

Seljuk Sultan's Courtier

The Seljuk Sultan's Courtier Disturbs Rūmī's Visit to his Father's Grave

Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (A Translation of Stars of the Legend), in Turkish

The translation was ordered in 1590 by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95) from the Persian abridgement of Aflākī.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

While meditating near his father's tomb, Rūmī is disturbed when the sultan's courtier, Valad-i Fakhr al-Dīn Shādid, in princely attire, rides his black horse through the cemetery. Rūmī strongly reproves the rider, who then loses control of his horse, falls to the ground, and is injured. Rūmī, with a gray beard, is at the upper right, surrounded by students. Two men with guns guard the entrance to the walled city in the background. The cemetery itself is located outside the city walls, as was the custom.

This miniature is part of a sixteenth-century manuscript account of the life and miracles of the Persian poet and mystic known as Rūmī. It is a Turkish translation of an abridged version of the original fourteenth-century Persian account by the dervish known as Aflākī.

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

The sixteenth-century miniatures presented here concern the life and miracles of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, called Mē vlāna (Our Master), the most famous member of the Mevlevī order and Persia's greatest Sufi mystic and poet. He was born in Balkh in 1207, but his family emigrated after his father foresaw the Mongol conquest. They eventually resettled in Konya, Turkey, then the capital of Anatolian Rūm (thus Rūmī), where the poet died on 17 December 1273.

Several Persian accounts of Rūmī's life have been written, the first by his son, Sultan Walad. The third, laden with moralizing miracle stories, was ordered by Rūmī's grandson Ulu ˓Ārif Chelebi. It was written by the dervish Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad, called Aflākī (d. 1360). Aflākī also incorporated verses from Rūmī's works, notably his six-volume Masnavī (a poetical form of rhyming couplets) and the Dīvān-i-Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, named after Shams of Tabriz, the mystic who changed Rūmī's life and transformed him into a poet when they met in 1244.

In 1590—three and a half centuries after Aflākī wrote his life of Rūmī—the Ottoman sultan Mūrad III ordered a Turkish translation of a 1540 abridged version of Aflākī's text entitled Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (Stars of the Legend). The translator was Darvīsh Mahmud Mesnevī Khān of Konya. Two illustrated copies of the Murād translation, both made in Baghdad, survive. One, dated 1599, is held by Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and has twenty-two miniatures. The other, richer manuscript is held by the Morgan. It dates to the 1590s and includes twenty-nine miniatures. They are all featured here, along with two folios from other collections that are believed to have once been part of the Morgan manuscript.

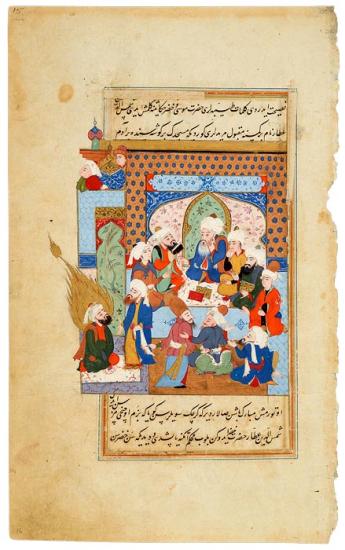

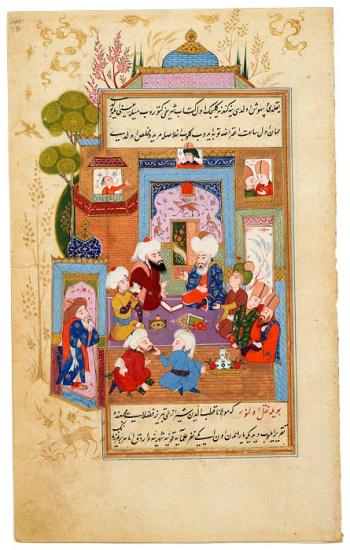

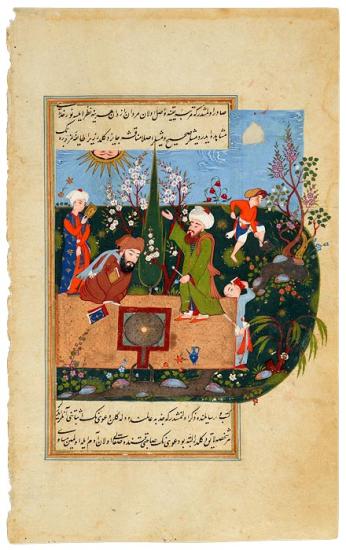

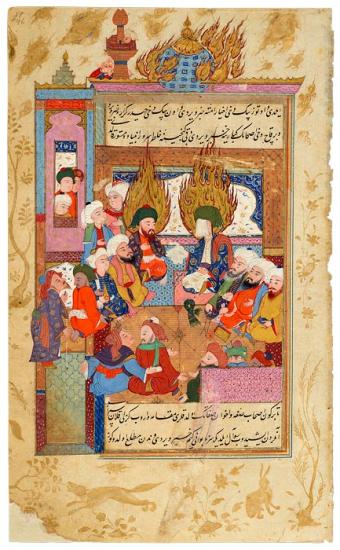

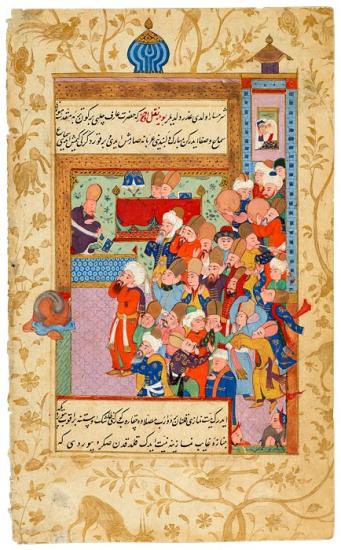

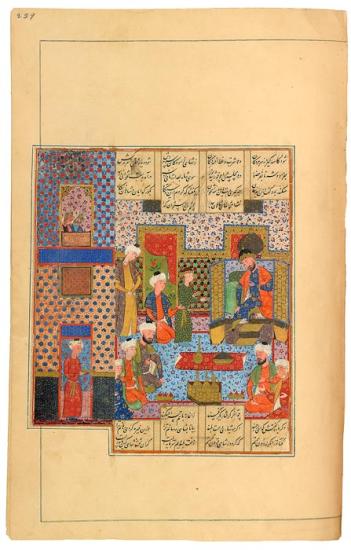

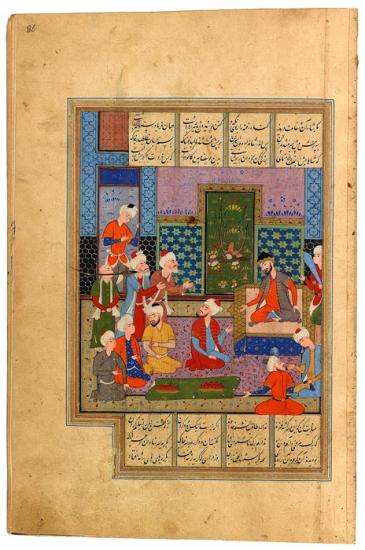

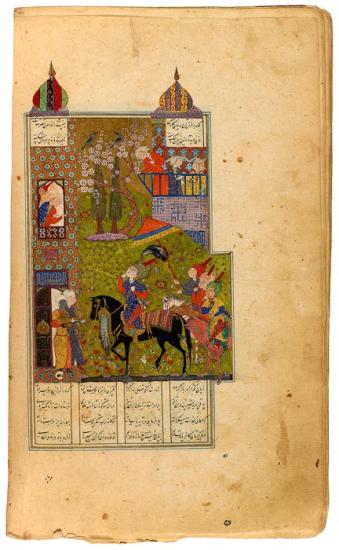

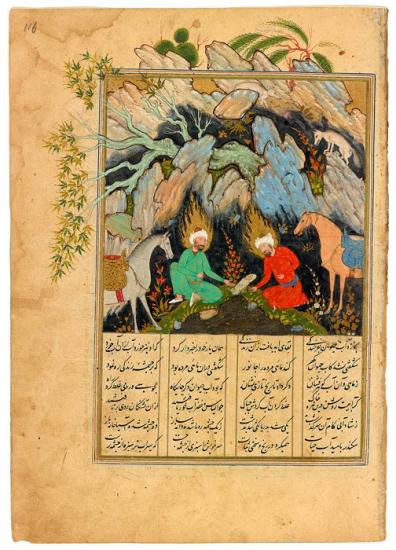

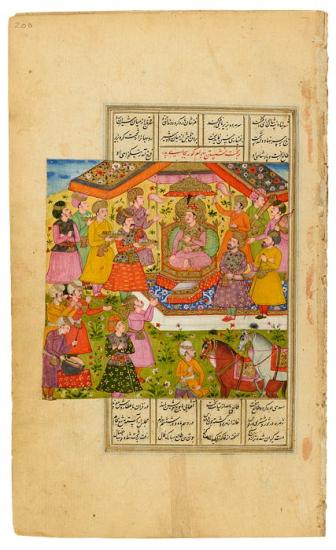

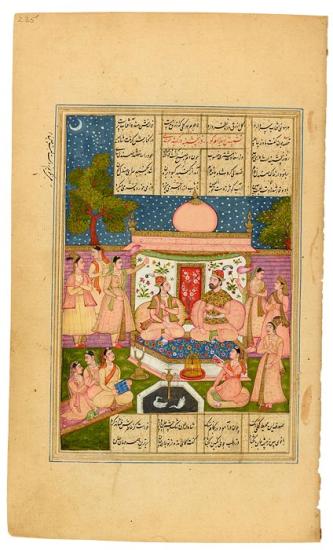

Sermon by Rūmī

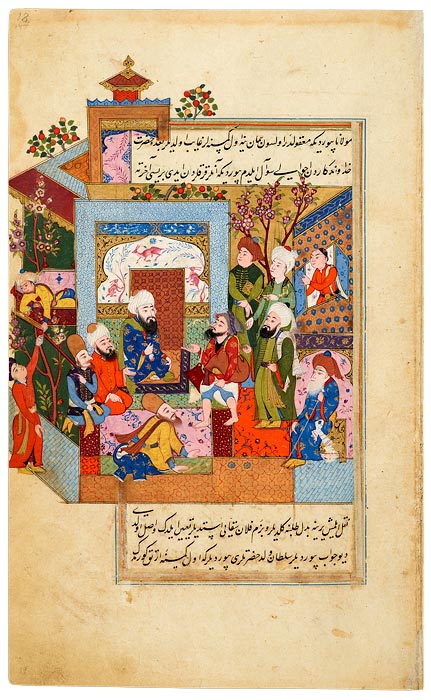

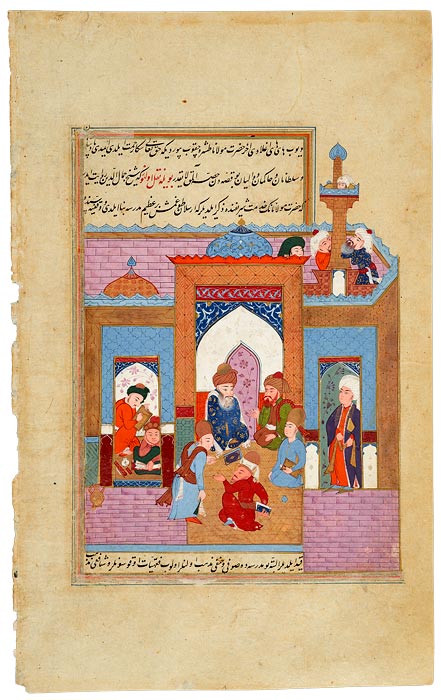

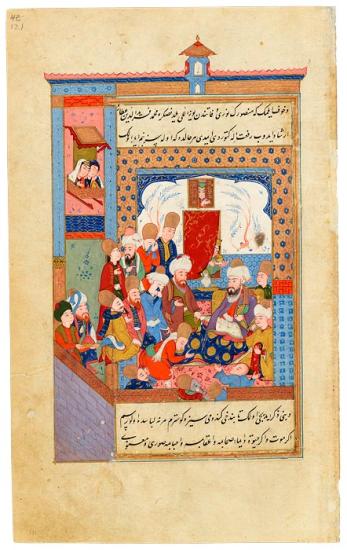

Khiżr Attends a Sermon by Rūmī

Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (A Translation of Stars of the Legend), in Turkish

The translation was ordered in 1590 by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95) from the Persian abridgement of Aflākī.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

According to the accompanying text, Rūmī, seated in the center, is explaining the stories of the prophets Khiżr and Mūsā (Moses) to his followers. Shams al-Din, a druggist, notices that Khiżr, dressed in his traditional green and adorned with the flaming halo designating a prophet, is sitting near a door of the mosque. When the druggist grabs Khiżr's robe in order to make a request, Khiżr tells him that he, like the other prophets, should seek guidance from Rūmī. Thought to be a contemporary of Moses, Khiżr is especially dear to the Sufis, who regard him as the initiator of those who walk the mystical path.

This miniature is part of a sixteenth-century manuscript account of the life and miracles of the Persian poet and mystic known as Rūmī. It is a Turkish translation of an abridged version of the original fourteenth-century Persian account by the dervish known as Aflākī.

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

The sixteenth-century miniatures presented here concern the life and miracles of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, called Mē vlāna (Our Master), the most famous member of the Mevlevī order and Persia's greatest Sufi mystic and poet. He was born in Balkh in 1207, but his family emigrated after his father foresaw the Mongol conquest. They eventually resettled in Konya, Turkey, then the capital of Anatolian Rūm (thus Rūmī), where the poet died on 17 December 1273.

Several Persian accounts of Rūmī's life have been written, the first by his son, Sultan Walad. The third, laden with moralizing miracle stories, was ordered by Rūmī's grandson Ulu ˓Ārif Chelebi. It was written by the dervish Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad, called Aflākī (d. 1360). Aflākī also incorporated verses from Rūmī's works, notably his six-volume Masnavī (a poetical form of rhyming couplets) and the Dīvān-i-Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, named after Shams of Tabriz, the mystic who changed Rūmī's life and transformed him into a poet when they met in 1244.

In 1590—three and a half centuries after Aflākī wrote his life of Rūmī—the Ottoman sultan Mūrad III ordered a Turkish translation of a 1540 abridged version of Aflākī's text entitled Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (Stars of the Legend). The translator was Darvīsh Mahmud Mesnevī Khān of Konya. Two illustrated copies of the Murād translation, both made in Baghdad, survive. One, dated 1599, is held by Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and has twenty-two miniatures. The other, richer manuscript is held by the Morgan. It dates to the 1590s and includes twenty-nine miniatures. They are all featured here, along with two folios from other collections that are believed to have once been part of the Morgan manuscript.

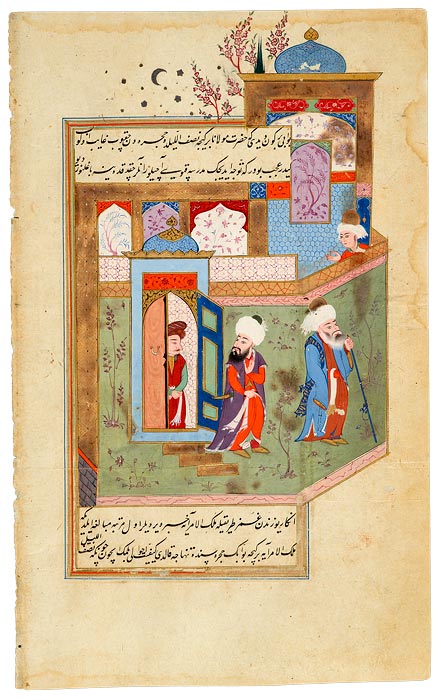

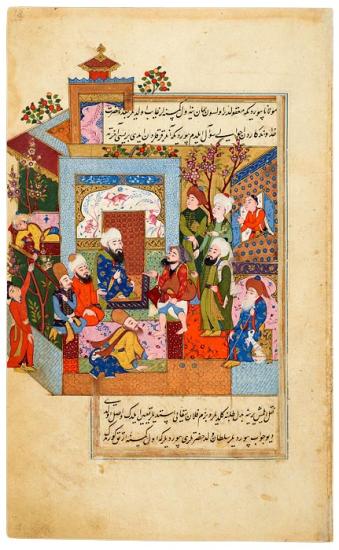

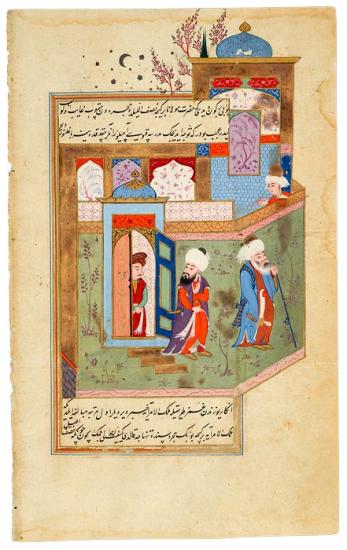

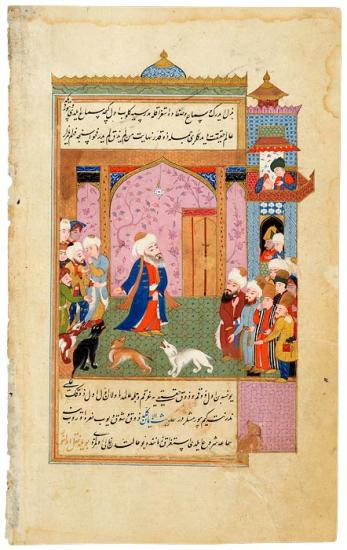

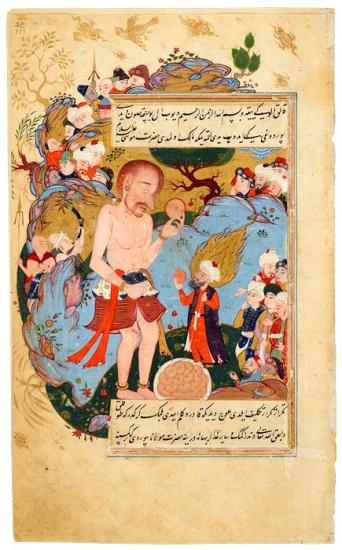

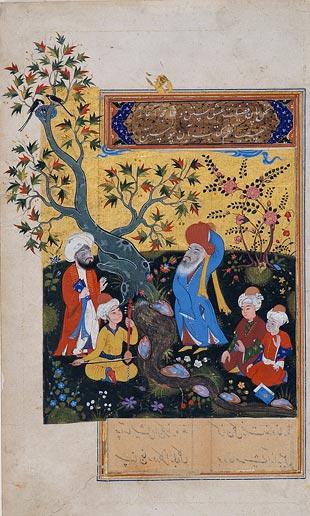

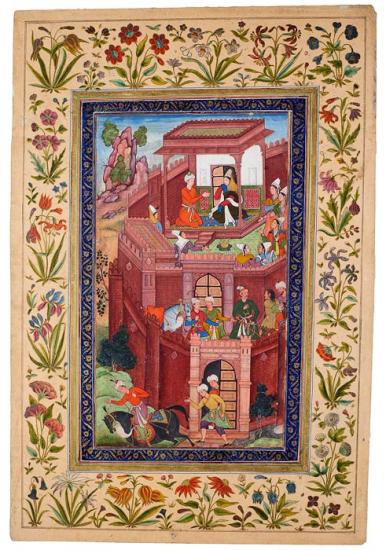

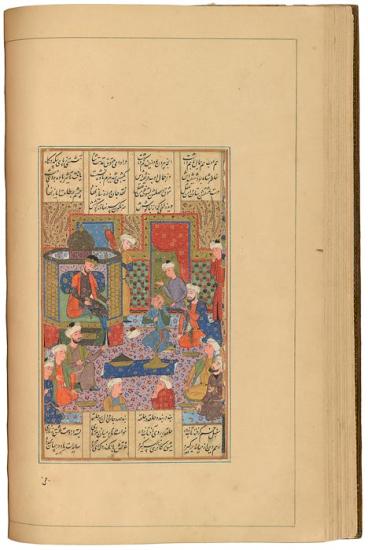

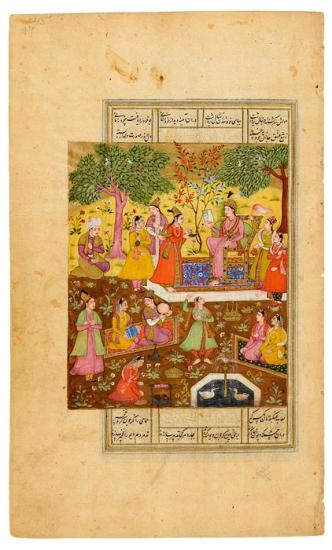

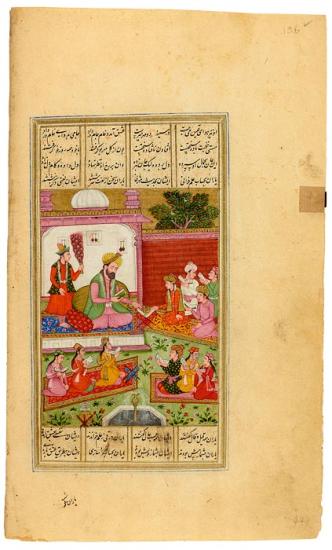

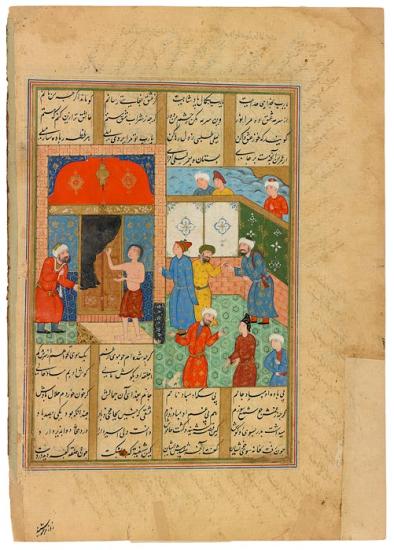

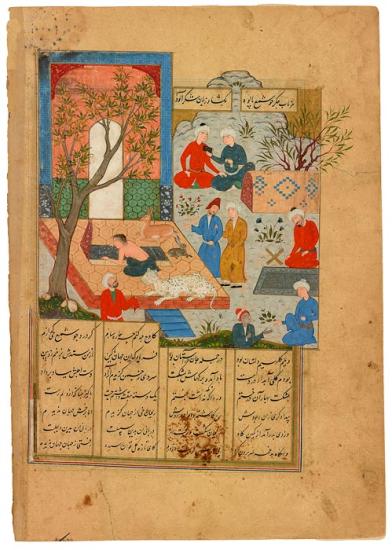

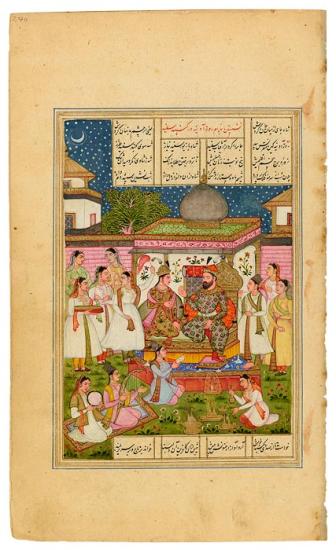

Three Saints

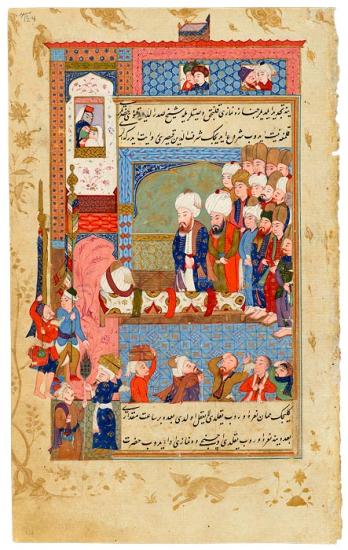

Three Saints Ask Rūmī for Permission to Take the Water Carrier of the Mevlevī Order with Them

Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (A Translation of Stars of the Legend), in Turkish

The translation was ordered in 1590 by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95) from the Persian abridgement of Aflākī.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

According to the story, not found in Aflākī's original Persian text but added by the Turkish translator, a delegation of three saints, all dressed in green, have come to visit Rūmī. They represent the forty saints that live in every generation, who, when one dies, choose a substitute. Here they ask Rūmī if they can take the water carrier of the Mevlevī order with them. The three saints stand behind the water carrier, who holds the large bag made of animal skin. Some genre scenes, as the doorkeeper at the right, and a youth offering an apple to a second youth on a balcony are not called for by the accompanying text, but are the kind of pictorial enrichments typical of the Baghdad school.

This miniature is part of a sixteenth-century manuscript account of the life and miracles of the Persian poet and mystic known as Rūmī. It is a Turkish translation of an abridged version of the original fourteenth-century Persian account by the dervish known as Aflākī.

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

The sixteenth-century miniatures presented here concern the life and miracles of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, called Mē vlāna (Our Master), the most famous member of the Mevlevī order and Persia's greatest Sufi mystic and poet. He was born in Balkh in 1207, but his family emigrated after his father foresaw the Mongol conquest. They eventually resettled in Konya, Turkey, then the capital of Anatolian Rūm (thus Rūmī), where the poet died on 17 December 1273.

Several Persian accounts of Rūmī's life have been written, the first by his son, Sultan Walad. The third, laden with moralizing miracle stories, was ordered by Rūmī's grandson Ulu ˓Ārif Chelebi. It was written by the dervish Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad, called Aflākī (d. 1360). Aflākī also incorporated verses from Rūmī's works, notably his six-volume Masnavī (a poetical form of rhyming couplets) and the Dīvān-i-Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, named after Shams of Tabriz, the mystic who changed Rūmī's life and transformed him into a poet when they met in 1244.

In 1590—three and a half centuries after Aflākī wrote his life of Rūmī—the Ottoman sultan Mūrad III ordered a Turkish translation of a 1540 abridged version of Aflākī's text entitled Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (Stars of the Legend). The translator was Darvīsh Mahmud Mesnevī Khān of Konya. Two illustrated copies of the Murād translation, both made in Baghdad, survive. One, dated 1599, is held by Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and has twenty-two miniatures. The other, richer manuscript is held by the Morgan. It dates to the 1590s and includes twenty-nine miniatures. They are all featured here, along with two folios from other collections that are believed to have once been part of the Morgan manuscript.

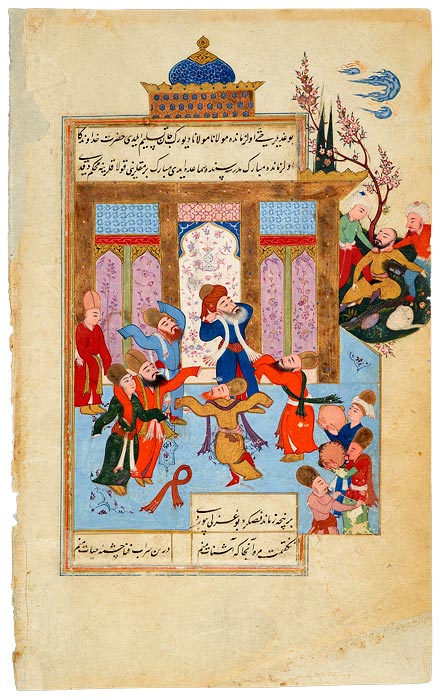

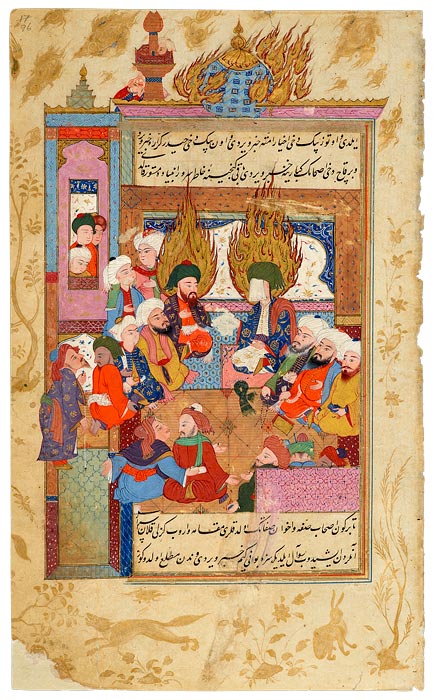

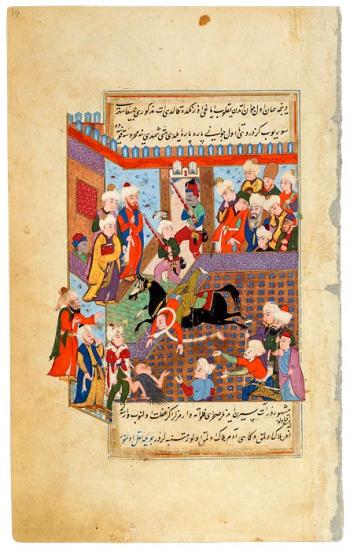

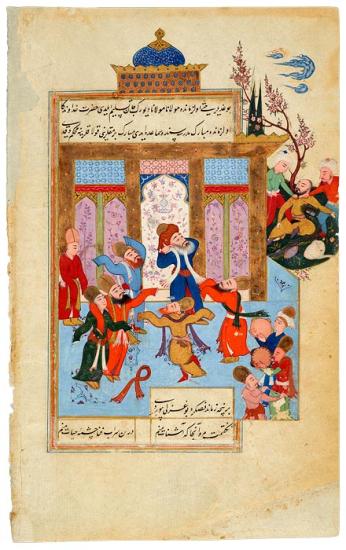

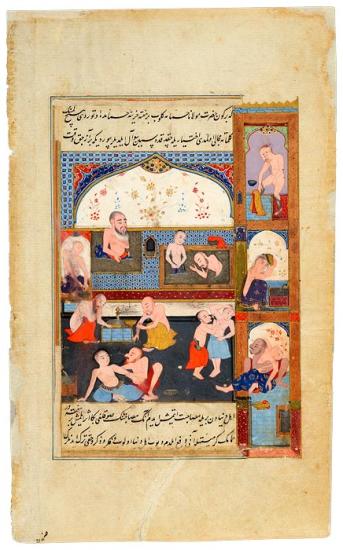

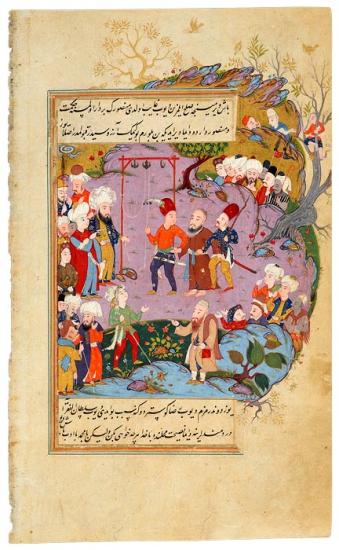

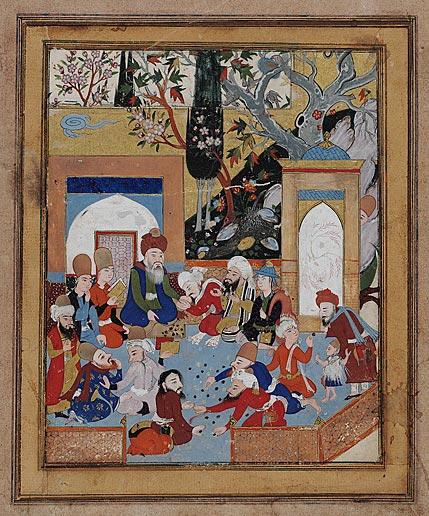

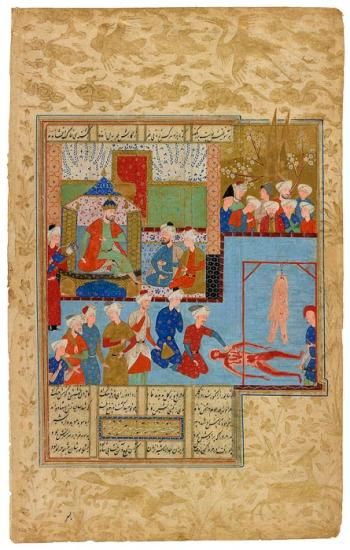

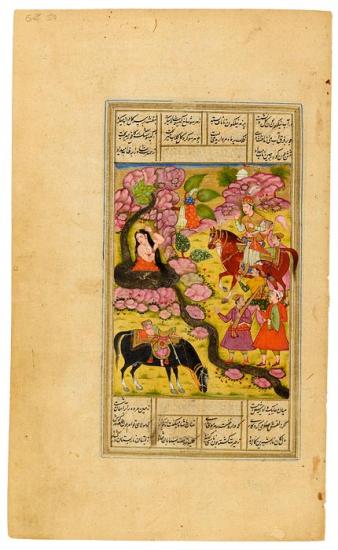

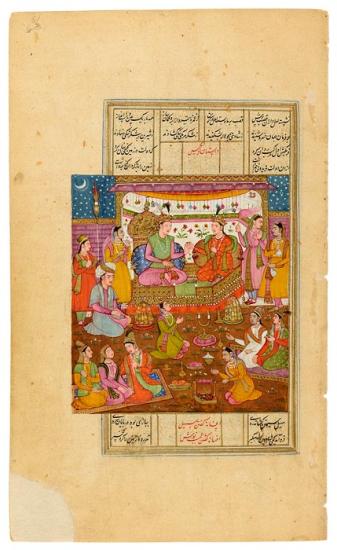

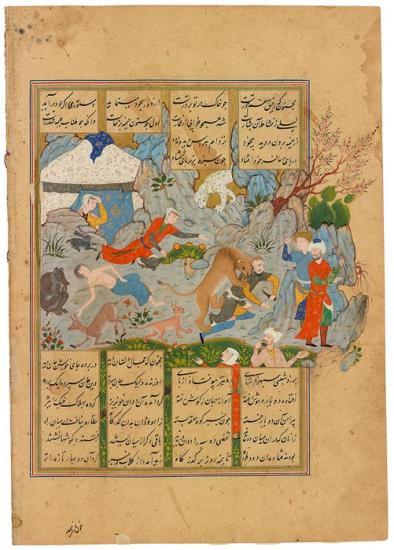

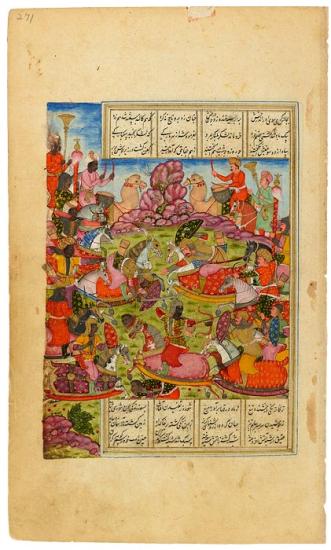

RūMī Stops His Ears

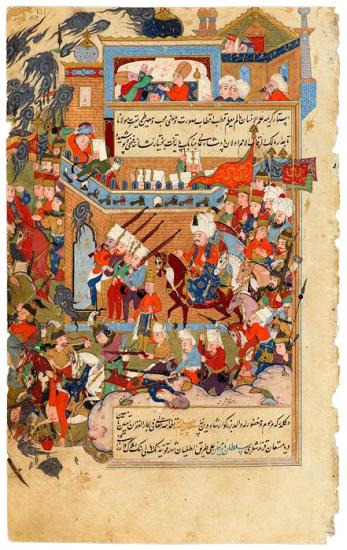

Participating in Samā˓, RūMī Stops His Ears Against the Cries of the Seljuq Sultan Rukn Al-Dīn Qlich

Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (A Translation of Stars of the Legend), in Turkish

The translation was ordered in 1590 by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95) from the Persian abridgement of Aflākī.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

According to the accompanying text, the Seljuq sultan Rukn al-Dīn Qilich Arslan IV (r. 1248–65) chose a questionable spiritual guide over Rūmī. Some days later he is strangled by some of his emirs. At the moment of the murder, Rūmī, participating in a mystical dance ceremony (samā˓), places his forefingers in his ears, leading a prayer for the dead. Rūmī later explained that the sultan had pleaded for his help, but he did not want to hear him, saying that a man's fate could not be changed. While the dervishes dance to the music of the flute and the tambourines, the noose is tightened around the sultan's neck.

This miniature is part of a sixteenth-century manuscript account of the life and miracles of the Persian poet and mystic known as Rūmī. It is a Turkish translation of an abridged version of the original fourteenth-century Persian account by the dervish known as Aflākī.

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

The sixteenth-century miniatures presented here concern the life and miracles of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, called Mē vlāna (Our Master), the most famous member of the Mevlevī order and Persia's greatest Sufi mystic and poet. He was born in Balkh in 1207, but his family emigrated after his father foresaw the Mongol conquest. They eventually resettled in Konya, Turkey, then the capital of Anatolian Rūm (thus Rūmī), where the poet died on 17 December 1273.

Several Persian accounts of Rūmī's life have been written, the first by his son, Sultan Walad. The third, laden with moralizing miracle stories, was ordered by Rūmī's grandson Ulu ˓Ārif Chelebi. It was written by the dervish Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad, called Aflākī (d. 1360). Aflākī also incorporated verses from Rūmī's works, notably his six-volume Masnavī (a poetical form of rhyming couplets) and the Dīvān-i-Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, named after Shams of Tabriz, the mystic who changed Rūmī's life and transformed him into a poet when they met in 1244.

In 1590—three and a half centuries after Aflākī wrote his life of Rūmī—the Ottoman sultan Mūrad III ordered a Turkish translation of a 1540 abridged version of Aflākī's text entitled Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (Stars of the Legend). The translator was Darvīsh Mahmud Mesnevī Khān of Konya. Two illustrated copies of the Murād translation, both made in Baghdad, survive. One, dated 1599, is held by Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and has twenty-two miniatures. The other, richer manuscript is held by the Morgan. It dates to the 1590s and includes twenty-nine miniatures. They are all featured here, along with two folios from other collections that are believed to have once been part of the Morgan manuscript.

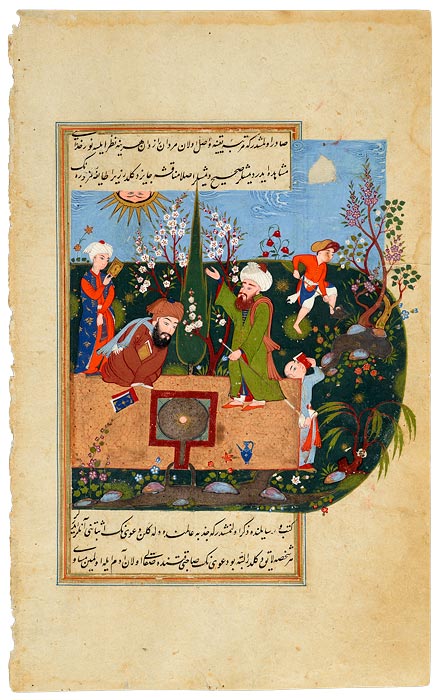

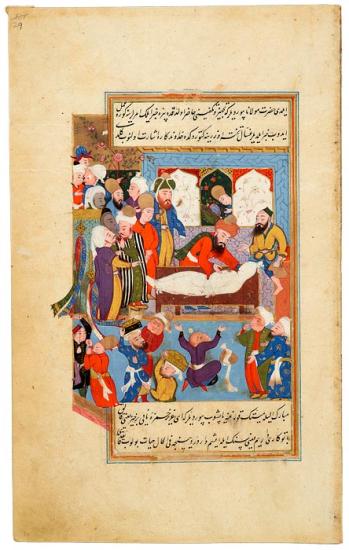

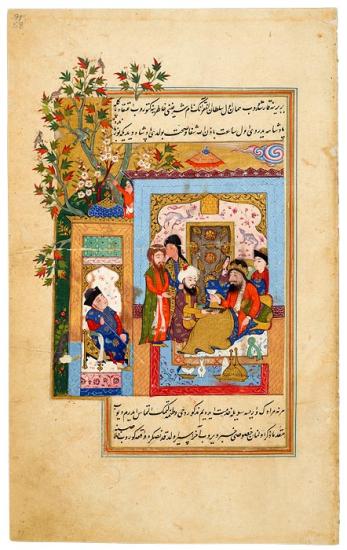

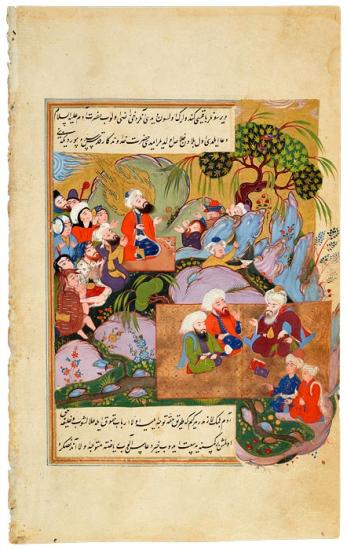

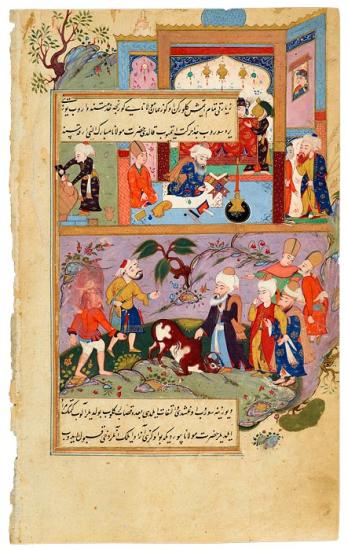

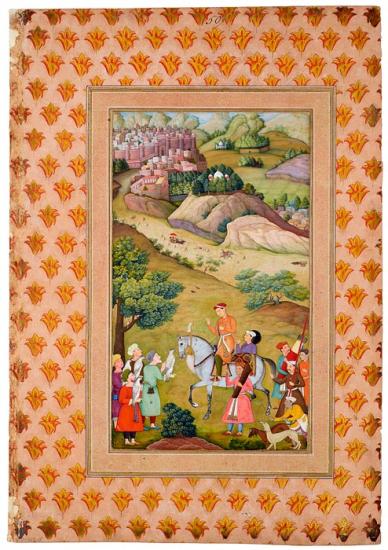

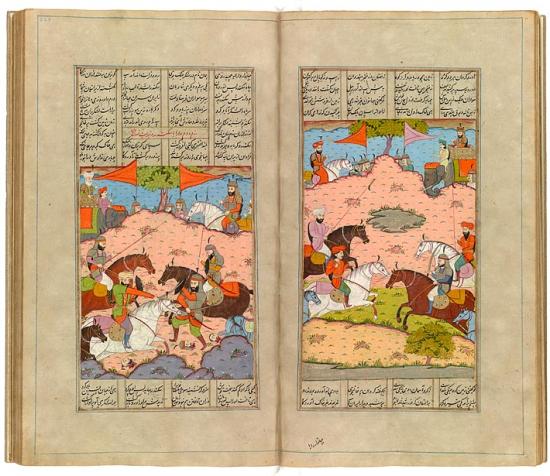

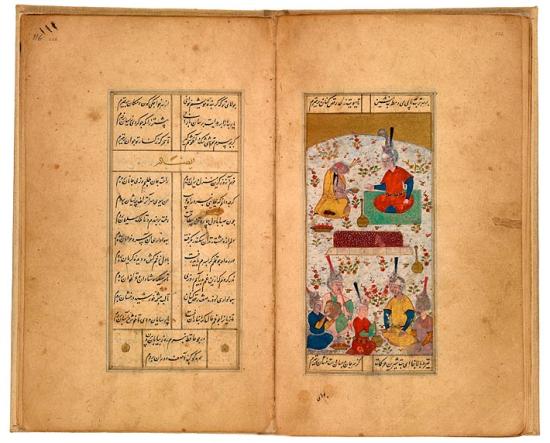

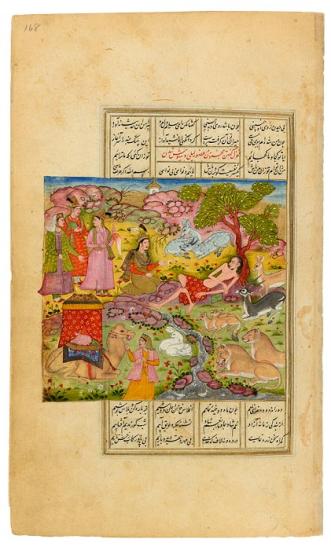

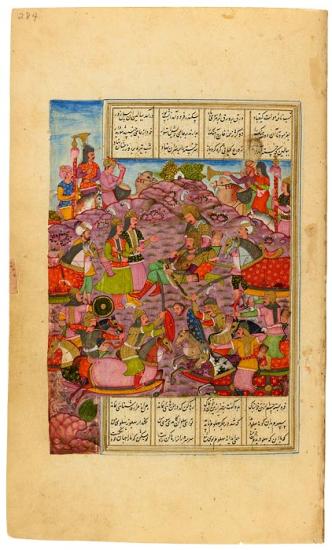

Rūmī Summons Ḥamza

Rūmī Summons Ḥamza, the Famous Flute Player, Back to Life

Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (A Translation of Stars of the Legend), in Turkish

The translation was ordered in 1590 by Sultan Murād III (r. 1574–95) from the Persian abridgement of Aflākī.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Ḥamza, the best flutist of the order, has just died. Rūmī raises the head of his corpse and miraculously restores him to life, saying, "My dear friend Ḥamza, arise!" Ḥamza then replies, "Lo, here I am!" takes up his flute, and sustains a religious festival for three days and nights. About one hundred Greeks witness the event and are converted to Islam. When Rūmī leaves, life departs from Ḥamza as well. In the left foreground, two youths hold religious standards, two men carry Qur˒an chests on their heads, and a dervish's felt hat and scarf have toppled to the ground.

This miniature is part of a sixteenth-century manuscript account of the life and miracles of the Persian poet and mystic known as Rūmī. It is a Turkish translation of an abridged version of the original fourteenth-century Persian account by the dervish known as Aflākī.

Rūmī, Persian Mystic And Poet

The sixteenth-century miniatures presented here concern the life and miracles of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, called Mē vlāna (Our Master), the most famous member of the Mevlevī order and Persia's greatest Sufi mystic and poet. He was born in Balkh in 1207, but his family emigrated after his father foresaw the Mongol conquest. They eventually resettled in Konya, Turkey, then the capital of Anatolian Rūm (thus Rūmī), where the poet died on 17 December 1273.

Several Persian accounts of Rūmī's life have been written, the first by his son, Sultan Walad. The third, laden with moralizing miracle stories, was ordered by Rūmī's grandson Ulu ˓Ārif Chelebi. It was written by the dervish Shams al-Dīn Aḥmad, called Aflākī (d. 1360). Aflākī also incorporated verses from Rūmī's works, notably his six-volume Masnavī (a poetical form of rhyming couplets) and the Dīvān-i-Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, named after Shams of Tabriz, the mystic who changed Rūmī's life and transformed him into a poet when they met in 1244.

In 1590—three and a half centuries after Aflākī wrote his life of Rūmī—the Ottoman sultan Mūrad III ordered a Turkish translation of a 1540 abridged version of Aflākī's text entitled Tarjuma-i Thawāqib-i manāqib (Stars of the Legend). The translator was Darvīsh Mahmud Mesnevī Khān of Konya. Two illustrated copies of the Murād translation, both made in Baghdad, survive. One, dated 1599, is held by Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, and has twenty-two miniatures. The other, richer manuscript is held by the Morgan. It dates to the 1590s and includes twenty-nine miniatures. They are all featured here, along with two folios from other collections that are believed to have once been part of the Morgan manuscript.

ḤalĀwiyya Madrasa