Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands

This exhibition explores the evolution of courtly clothing from the "Fashion Revolution" around 1330 to the flowering of the Renaissance in France following the accession of King François I in 1515. During this period, the modern notion of changing fashion was reborn. Because few actual garments from the Middle Ages survive, we use the art of this era — illuminated manuscripts and early printed books — to reveal its evolving styles. Concentrating on France and Flanders, this show also makes the occasional foray into England, Germany, and Holland. In addition, the exhibition touches on the potential impact of political unrest and social upheaval on the history of fashion during one of the world's more calamitous eras. The vicissitudes of the Hundred Years' War, the occupation of Paris by the English, and the arrival of the Italian Renaissance in northern Europe, for example, influenced clothing styles. Also explored here are the ways in which artists used clothing (garments actually worn) and costume (fantastic garments not actually worn) to help contemporaneous viewers interpret a work of art. The garments depicted were often encoded clues to the wearer's identity and moral character.

This exhibition is generously underwritten by a gift in memory of Melvin R. Seiden and by a grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Major support is provided by The Coby Foundation, Ltd., with additional assistance from the van Buren family in memory of Dr. Anne H. van Buren, and from the Janine Luke and Melvin R. Seiden Fund for Exhibitions and Publications.

Overview

The Fashion Revolution Begins

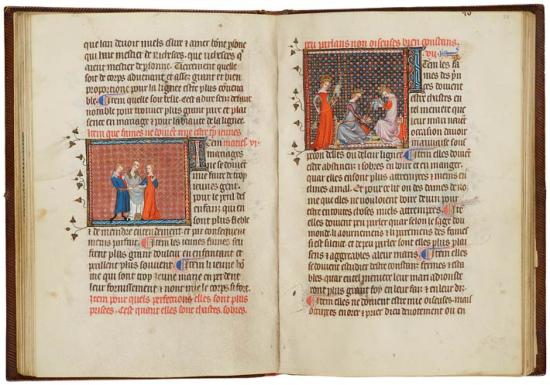

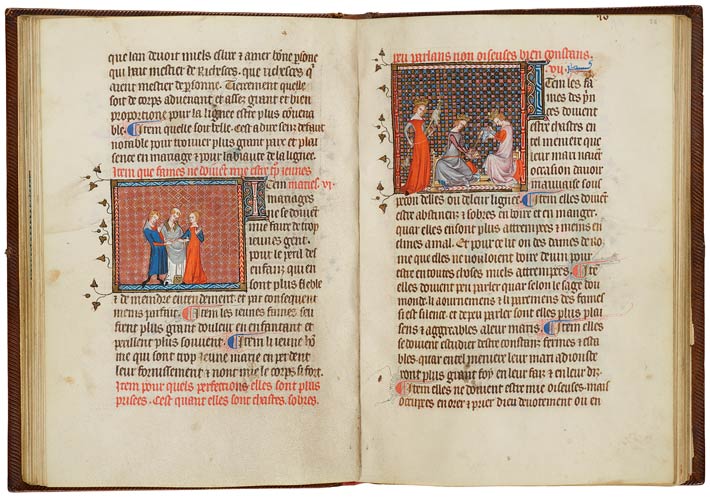

Instructions for Kings, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

The blue surcot worn by the groom in the left miniature is shorter than before. While his skirt is still full, the bodice of his surcot is now tighter, made possible by the invention of the set-in sleeve. His blue sleeves terminate at the elbow in decorative extensions, revealing the red sleeves of his kirtle. His chaperon rests on his shoulders. The bride and the three princesses in the right miniature all wear the open-sided surcot over kirtles with tight sleeves. Low, horizontal necklines reveal their bare necks and the tops of their shoulders.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

The Fashion Revolution Explodes

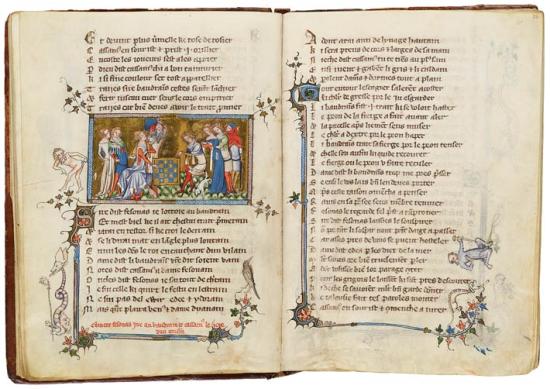

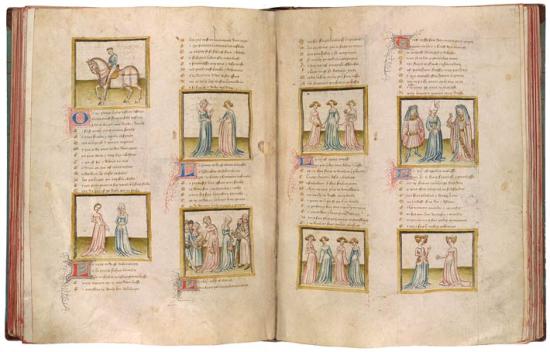

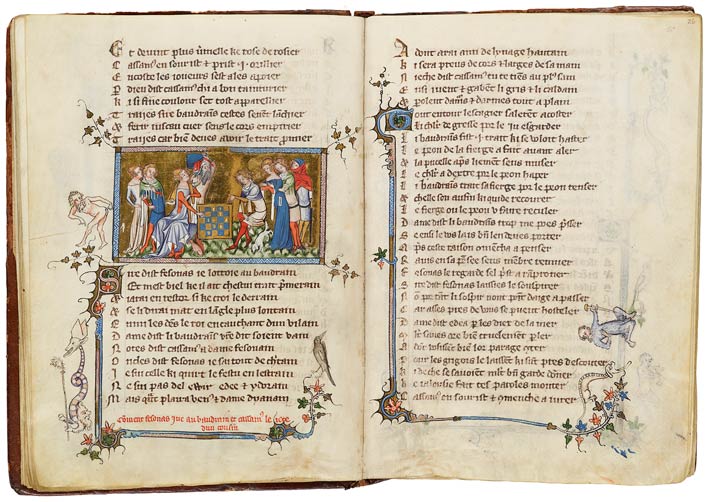

Jacques de Longuyon, Vows of the Peacock, in French

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

The four young men in this miniature are all dressed at the height of the new fashion. They wear the new short garment, the cote hardy: buttoned down the front, it is tight at the skirt, bodice, and sleeves. All sport chaperons, two of which are dagged (cut into decorative strips). Some wear delicate shoes, while the youth in blue wears chaussembles: hose with leather soles. The two women at the left wear the open surcot. The woman in blue wears the closed surcot, furnished with a lined slit for access to the kirtle. She also wears tippets: thin decorative bands of cloth falling from the elbow.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

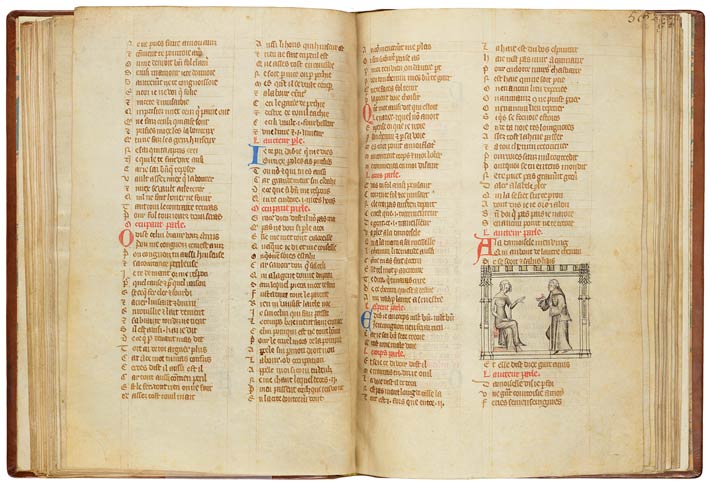

Idleness Personified

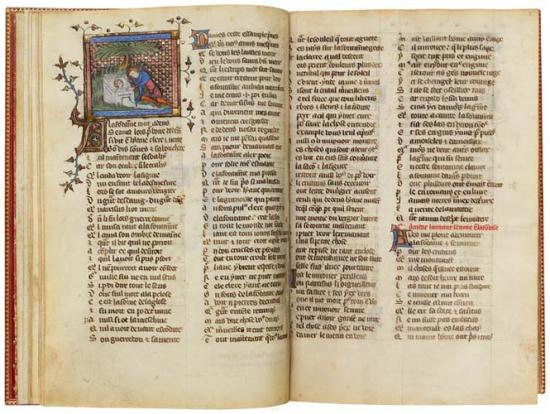

Pilgrimage of Human Life, in French and Latin

Purchased, 1931

In this allegorical treatise, Idleness is personified as a lazy but beautifully dressed and perfectly coiffed young woman. The tight bodice of her surcot cinches her high, narrow waist, emphasizing the curves of her bosom and belly. Slender tippets fall from her elbows, and the pointed tips of her narrow shoes poke from beneath her hem. A low neckline exposes her neck and the tops of her shoulders, while braided hair frames her face. She gestures condescendingly toward the humble pilgrim, dressed like a monk and equipped with a walking stick and satchel of provisions.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

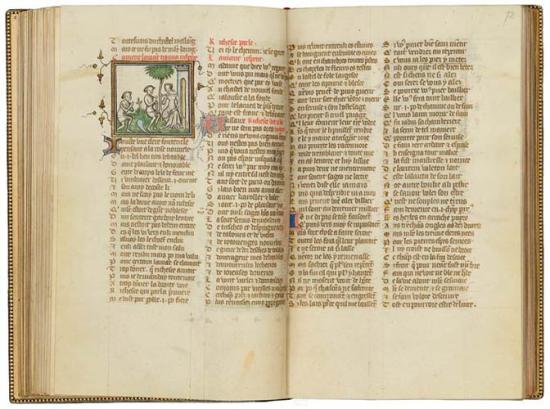

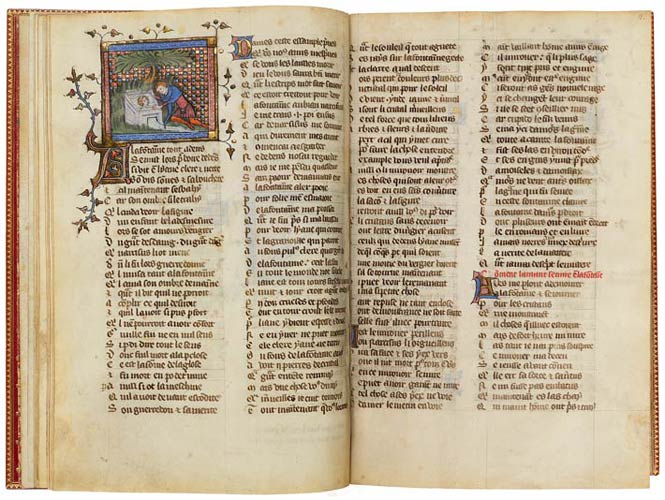

Narcissus Admires Himself

Romance of the Rose, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1904

Narcissus admires his handsome reflection in a fountain. His hair is fashionably wavy and features a dorlott: a curl or bang centered above the forehead. His cote hardy is tight on the bodice with a loose, gored skirt with a dagged hem. A purse, called a gipser, dangles from his thin belt. His blue chaperon, embroidered with a decorative hem, hangs foppishly loose around his shoulders. He wears orange hose and elegant shoes with open frets.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

A Well-Dressed Lucretia Commits Suicide

The Game of Chess Moralized, in French

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Lucretia's surcot has a fashionably tight bodice and sleeves, from the elbows of which hang slender tippets. The neckline is curved, rising in front but falling off the shoulders. The braids of her hair have been folded along the slanted posts of a tressour, framing her face. Her father, husband, and friends are all dressed in tight cotes hardy with dagged hems. Lucretia's father also wears tippets from his sleeves and a dagged chaperon. The men sport wavy hair with a dorlott: a curl or bang above the forehead.

Fashion Revolution

The "Fashion Revolution" began around 1330 with the invention of the set-in sleeve. Earlier garments were T-shaped, with sleeves of a piece with the body or sewn on a flat seam. The new technique (still in use today) cut sleeves with rounded tops and gathered them along basted threads into armholes in the bodice. This new tailoring, combined with the use of multiple buttons, made possible a snugly fitted bodice and tight sleeves. While providing more freedom of movement, the new garment for men—the cote hardy—also revealed the shapes of the wearer's torso and arms. The "Fashion Revolution" gave birth to men's modern dress, creating an outfit that was sharply differentiated from the dress of women.

Women's fashions, however, were also affected. Tighter bodices and sleeves became popular, as did exposed necks and shoulders. The sides of the outer garment, the surcot, now sometimes featured seductively large, peek-a-boo openings.

Men—and some women—turned the chaperon (a hood with an attached cape and tail) into a fashion accessory that lasted over a hundred years.

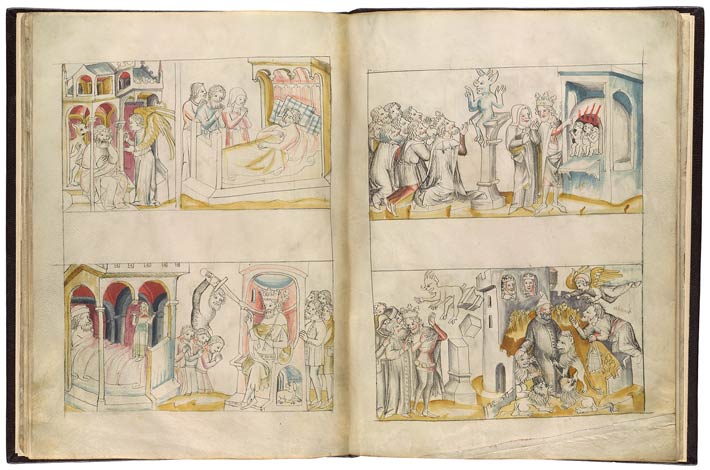

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

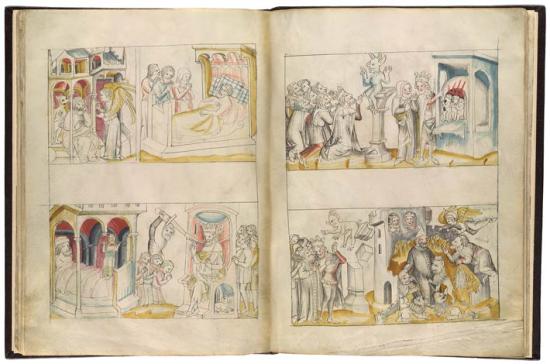

History Bible, in Latin and German

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907

Alexander the Great Fashionista

Alexander the Great, especially in the scenes at the lower right, exhibits the wasp waist and bulbous torso that characterize the fashionable look for men during the second half of the fourteenth century. Buttons and padding in the doublet's chest and shoulders helped achieve this hourglass silhouette. A low-slung "Bohemian" girdle and pouleines (pointed shoes) complete the look. The women in these vignettes, including Candace (to whom the king makes love), are depicted with similar silhouettes. The woman's distinctively frilly ruffled hood is particular to Germany and parts of the Netherlands but not France.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).

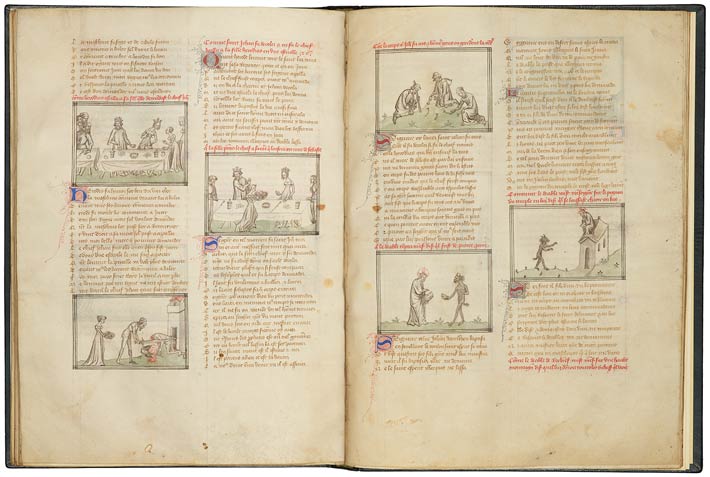

Salome and Herodias in Killer Clothes

History of the Bible and of the Assumption of Our Lady, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Salome, represented three times in the miniatures at the left, wears a cote hardy with a voluminous skirt but with contrastingly tight bodice, bosom, and sleeves. Except in the top scene, where she wears a coronet, the young girl's hair is loose and falls over her ears — a sign of her maidenhood. In the second miniature, her mother, Herodias, is similarly dressed, but in the first vignette she wears, befitting her queenly status, a surcot with extremely wide side openings. Her braided hair, along with the posts of her tressour, frames her face.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).

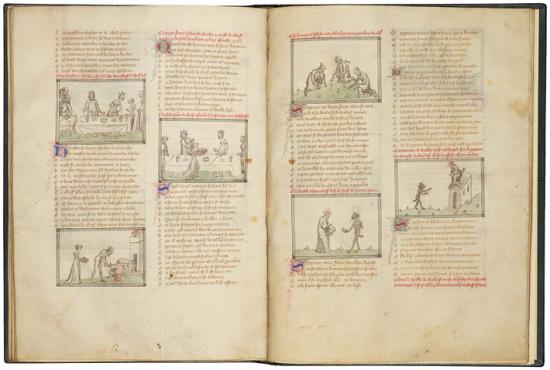

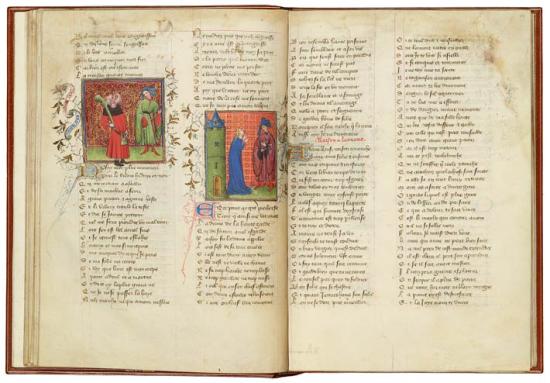

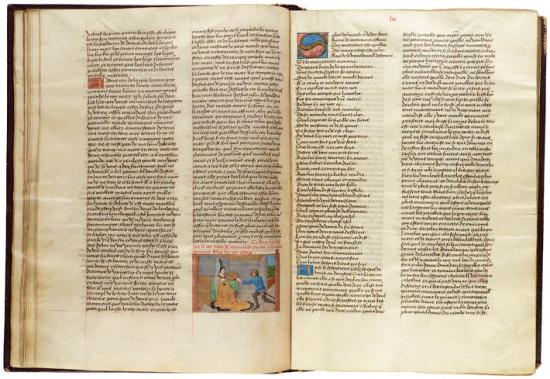

Women Encounter Bad Advice and Irrationality

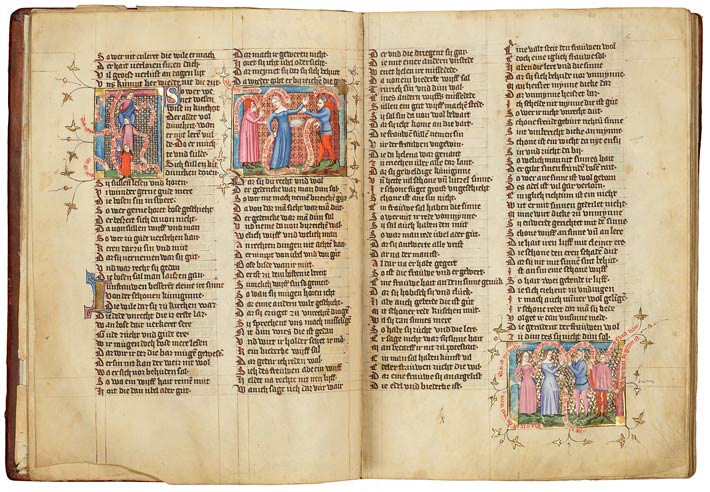

Der Wälsche Gast, in German

Illuminated by the Kuno von Falkenstein workshop

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

The women in this allegorical treatise wear cotes hardy similar to their French contemporaries (albeit on slightly plumper figures). Their loose skirts contrast with tight bodices, bosoms, and sleeves, the ends of which are slightly funnel shaped. In the second miniature at the left, the young male personification of Bad Advice wears a wasp-waisted, stuffed doublet. His pouleines (pointed shoes) are particularly elegant with open fretwork. In the miniature at the right the older male personification of Irrationality is similarly dressed. Behind him, the young male Seducer wears a dashing pink paltock (a loose jacket with sleeves) over his doublet.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).

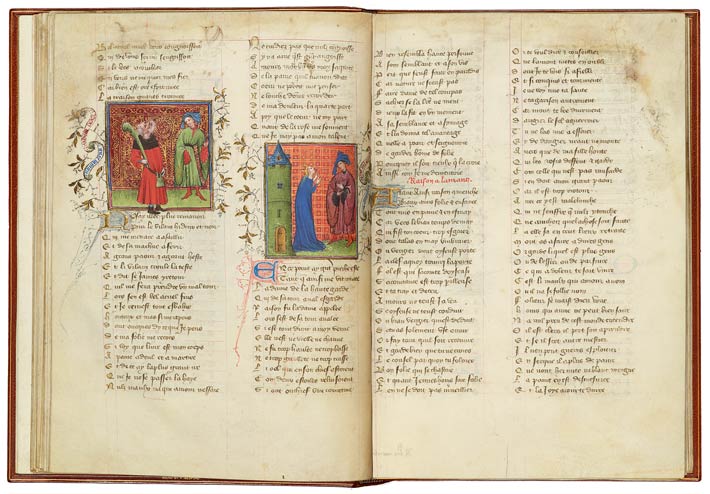

The Lover Encounters Wealth

Romance of the Rose, in French

Illuminated by the Master of the Bible of Jean de Sy

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

The Lover, the protagonist of the Roman de la rose, is shown twice in this miniature. He is depicted first approaching, then addressing the female personification of Wealth. He wears the hourglass-shaped doublet, with a low, narrow belt, and chaussembles (hose equipped with leather soles). His loose hair, parted in the middle, is that of a youth. Lady Wealth wears a cote hardy with tippets: slender strips of cloth attached to her upper arms (instead of the elbows, as was more customary). Her shoulders are draped with a chaperon, with its hood thrown back, and braids frame her face.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).

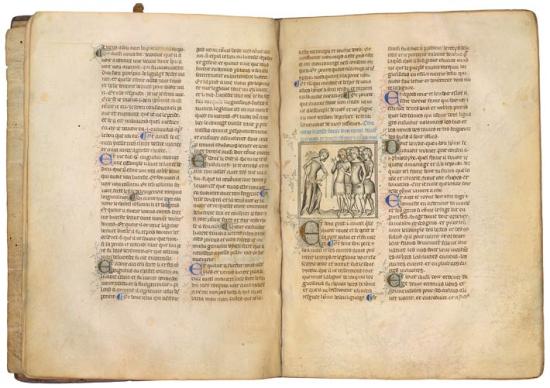

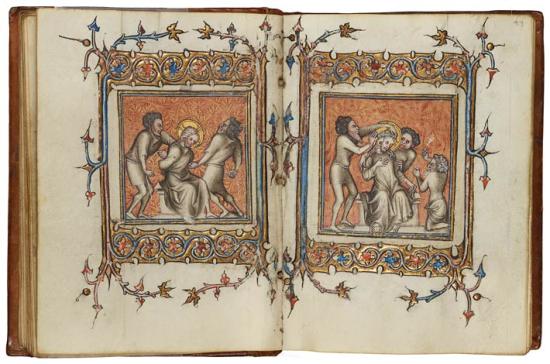

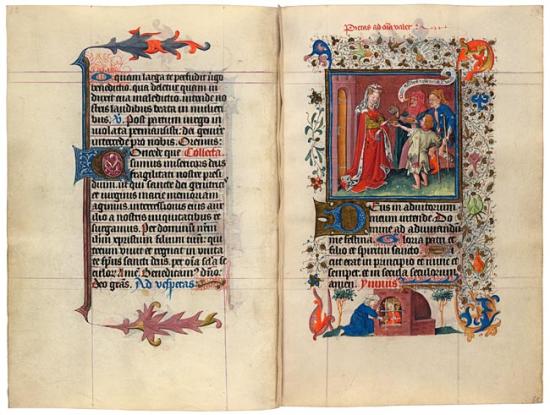

Tormentors Are Always Well Dressed

Book of Hours, in Latin and French

Illuminated by the Master of the Bible of Jean de Sy

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

It was an unwritten rule for medieval artists that Christ was never fashionable. The opposite, however, applied to torturers and executioners, whose foppish obsession with elegant clothing was a reflection of their depravity. The two tormentors at the left wear the cote hardy with a loose bodice and a knee-length skirt. At the right, the kneeling man, who mockingly offers the Savior a reed as a scepter, also wears the cote hardy, the skirt of which is tucked into his belt. The bearded man, who rams the Crown of Thorns onto Christ's head, wears the shorter and tighter doublet.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).

Fashion in a Missal

Single leaf from a Missal, in Latin

Illuminated by Meister Bertram von Minden

Purchased, 1958

Perhaps the doves carried by the Virgin Mary's attendant in the large scene inspired the illuminator to enliven the borders of this Missal leaf with avian themes. (The text is for the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin, celebrated on 2 February.) The young people hawking at the bottom left are fashionably dressed: the youth wears a red pourpoint with a dagged hem, a particularly tight chaperon, narrow belt, and open shoes. The women wear cotes hardy snug on the arms and upper body. The girl at the right has a tight red chaperon and, on top of that, a fanciful crown.

Wasp Waists and Stuffed Shirts

The second half of the fourteenth century was a bleak period in French history. The Black Plague, which first struck in 1348, was a recurring horror. As the Hundred Years' War dragged on, France suffered devastating defeats by the English. Following the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, King John II was captured and taken to London as a prisoner. Fashions changed little during this period.

Men's fashion was dominated by the pourpoint: a close-fitting doublet influenced by the military. With a short flaring skirt and a cinched waist, the pourpoint was padded at the chest and shoulders, giving its wearer a distinctive hourglass silhouette. Pouleines, long pointed shoes, and belts—slender, or the thick "Bohemian" girdle—worn low on the hips complimented the look.

The cote hardy—an outer garment for women—while retaining its voluminous skirt, got even tighter at the bodice, bosom, and sleeves. The resulting look paralleled that of men's fashion. Tippets, decorative strips of cloth hanging from the arms, remained popular. Both men and women continued to wear the chaperon (the hood with attached cape and tail).

Luxury in a Time of Madness

Romance of the Rose, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1900

The Lover Encounters Danger and Reason

The Lover, protagonist of the Roman de la rose, is always fashionably dressed. In these miniatures he encounters personifications of Danger (an old man with a club) and Reason (a crowned woman). In both scenes he wears the characteristic garment of this period, the houpeland. Both the green and purple houpelands are calf length and feature large poke sleeves. The floppy dagged sleeves of the pourpoint he wears beneath the houpeland are visible at his wrists. In both miniatures the Lover wears chaussembles and a blue chaperon with its cape and cornet tied up into the shape of a fish.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

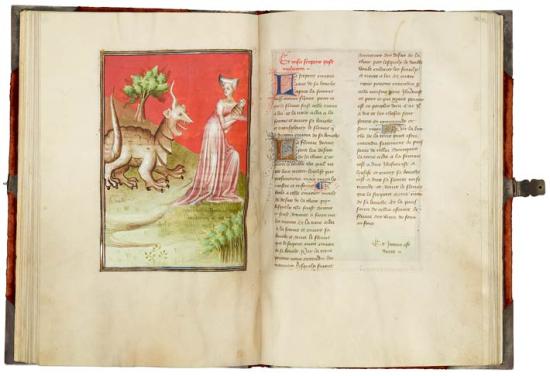

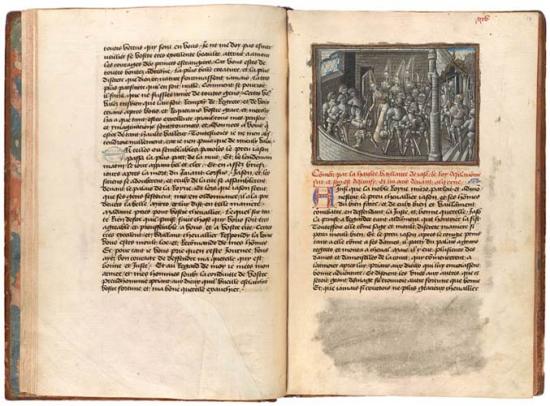

Personification of the Church is Conservatively Dressed

Apocalypse, with commentary, in French

Illuminated by the eponymous Master of the Berry Apocalypse

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

The beast of the Apocalypse pursues a woman above whose head is inscribed L'eglise. Symbolizing the Church, this woman is purposefully not dressed in the period's luxurious houpeland. Instead, she wears only the traditional cote hardy. With its tight sleeves (worn here without tippets) and bodice but voluminous, trailing skirt, it is very much like the cotes hardy worn by the women in the previous section. Her headgear, too, is quite basic: double veils draped atop hair coiled over her ears.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

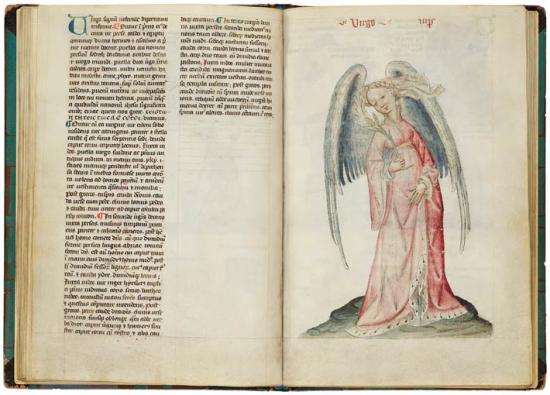

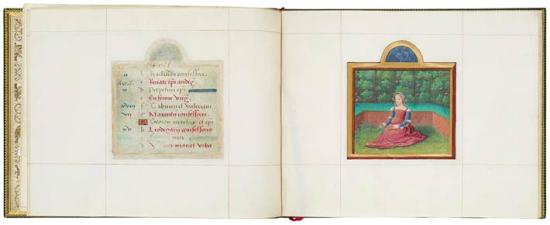

Like a (Well-Dressed) Virgin

Astrological Treatises, in Latin

Purchased, 1935

In this astrological treatise, the zodiacal sign of Virgo (the Virgin) is represented by an extremely well-dressed maiden. She wears a trailing pink houpeland with bombard sleeves. The houpeland's skirt is luxuriously lined and hemmed with ermine, while its collar is lined with a second, tan fur. At her wrists we can see the sleeves of her symbolically pure-white cote hardy. As was the style, Virgo wears her belt very high, just beneath the bosom, over a gently swelling stomach. Her braided hair is uncovered; a simple transparent veil wafts from the back of her head.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

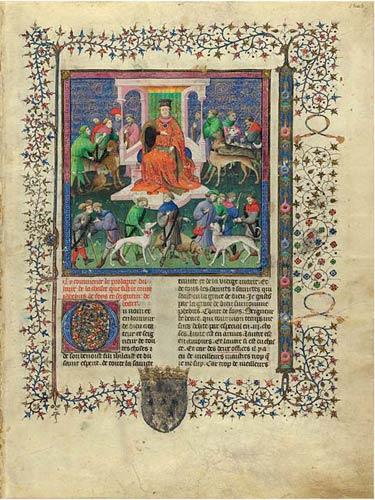

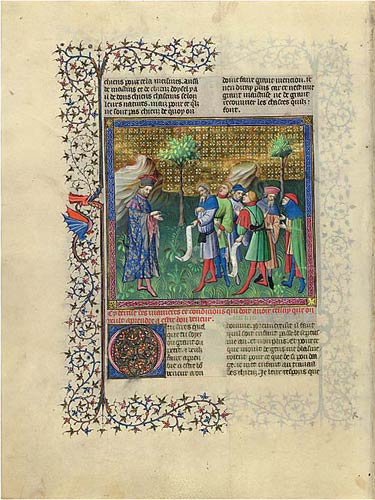

Portrait of the Author: Gaston Phoebus

Livre de la chasse, in French and Latin

Illuminated possibly by the Josephus Master and the Bedford Master

Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983

Gaston III, count of Foix (1331–91), was called Phoebus because of his golden hair or handsome features. He composed this treatise on hunting and dedicated it to his fellow hunter, Duke Philip the Bold of Burgundy. The manuscript opens with an author portrait showing Gaston enthroned, directing the hunters and dogs gathered around him. He wears a voluminous fur-lined orange houpeland with elaborate gold embroidery and large bombard sleeves. The poke sleeve of his black pourpoint is visible on his right arm. The narrow cape of his chaperon is draped around his neck and a tall bonnet sits atop his head.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

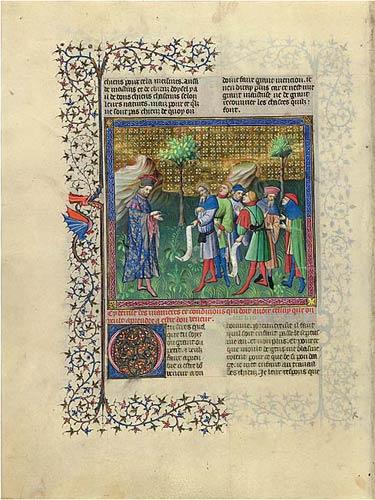

The Well-Dressed Trainer of Huntsmen

Livre de la chasse, in French and Latin

Illuminated possibly by the Josephus Master and the Bedford Master

Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983

Huntsmen, as young pages, were expected to know their hounds by name, appearance, and color. They are instructed in this miniature by an extremely fashionably dressed trainer. He wears a blue fur-lined, midcalf houpeland with gold embroidery and dagged bombard sleeves. Pink accents his collar and epaulettes as well as his matching chaussembles and the dagged sleeves of his pourpoint. His tall black bonnet is dramatically lined in red.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

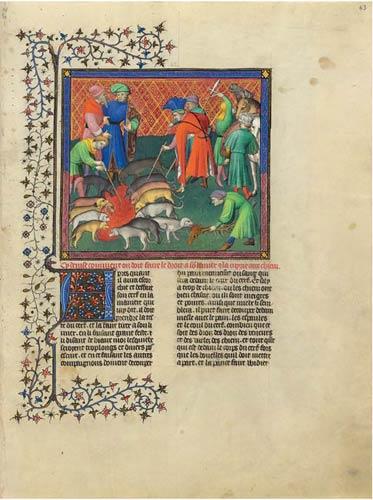

No Bloodstains on These Clothes

Livre de la chasse, in French and Latin

Illuminated possibly by the Josephus Master and the Bedford Master

Illuminated possibly by the Josephus Master and the Bedford Master

Two huntsmen wear the fashionable calf-length houpeland in this miniature. To the left, the man in the blue fur-lined houpeland also wears a capeline, or "bag hat" (as do the man he speaks with and the youth at the lower right). The "bag hat" would remain popular until around 1430. The other hunter wears an orange ermine-lined houpeland. His hat, with its crown of blue ostrich feathers, is the artist's invention. Behind him, two assistants wear their chaperons in imaginative ways. The cape of the yellow chaperon falls down the back of one helper, while the cape of the white chaperon worn by the other juts straight up, imitating a tall bonnet.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

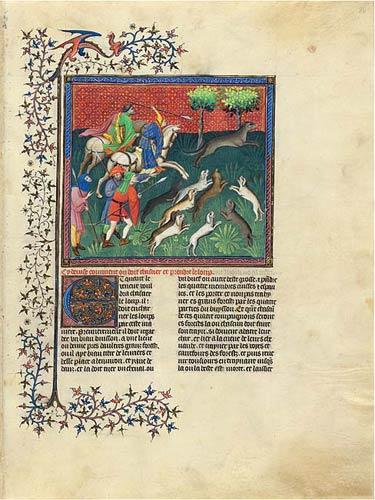

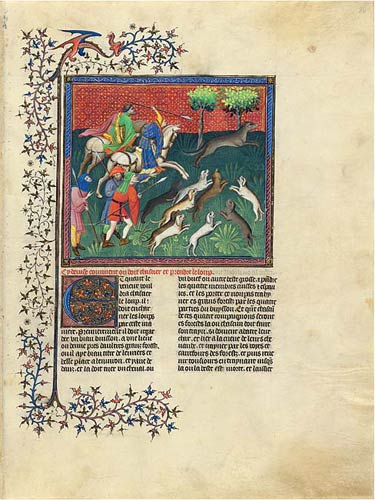

The Fashionable in Pursuit of the Wolf

Livre de la chasse, in French and Latin

Illuminated possibly by the Josephus Master and the Bedford Master

While their motley crew follows on foot, two well-dressed hunters pursue the hated wolf on horseback. The huntsman in blue wears a fur-lined midcalf houpeland elaborately embroidered in red, white, and gold. Around his high waist is a gold belt from which fall gold chains terminating in bells. Orange provides the accent on his "bag hat" and matching chaussembles. Behind him rides a second hunter in a houpeland partied in green and pink and with especially large bombard sleeves. He wears an elaborate gold baldrick diagonally across his back. The rolled tube of cloth on his head is a burlet.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

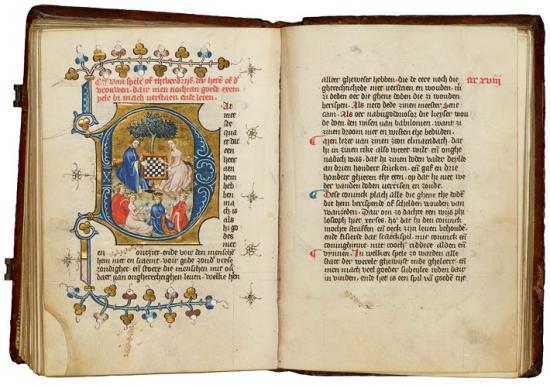

Royals Dressed for Edifying Leisure

Table of Christian Faith, in Dutch

Illuminated by the Masters of Dirc van Delft

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1924

This is one of the earliest copies of the encyclopedia that van Delf wrote during the early fifteenth century. The miniature opens the chapter on games deemed suitable for royals; chess was considered an appropriate entertainment. A king and his queen play chess (although not with pieces, which the artist seems to have forgotten). He wears a luxurious fur-lined houpeland with a high neck and large bombard sleeves. His more humbly attired wife wears a simple cote hardy. A woman in a similar pink cote hardy plus two men and another woman in voluminous houpelands occupy the foreground.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

Delilah Dressed for Success

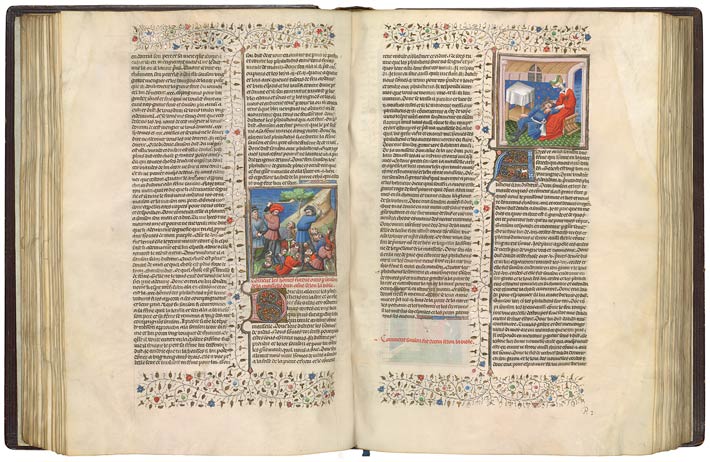

Bible historiale, in French

Illuminated by the workshop of the Boucicaut Master

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Taunted by the Philistines, a swashbuckling Samson slew a thousand of them with the jawbone of an ass, as depicted in the left miniature. They got their revenge, bribing Delilah to solve the mystery of his superhuman strength. She then got Samson drunk and cut off the source of his power — his hair. Delilah wears a trailing, high-waisted houpeland with bulbous sleeves and an open V-shaped collar. The horns of her temples (hennin), stretching wider than her shoulders, are surmounted by a decorative green burlet from which hangs a short veil. The horizontal embroidery and knotted sash worn by Samson signify his exoticism.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

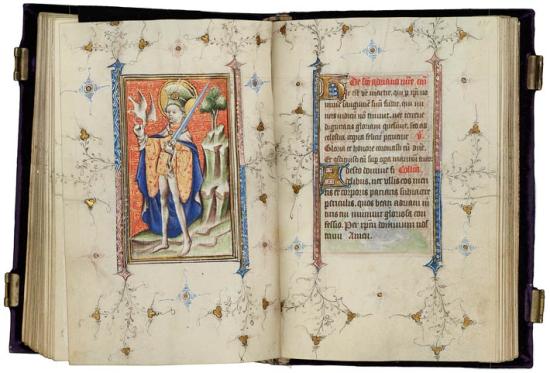

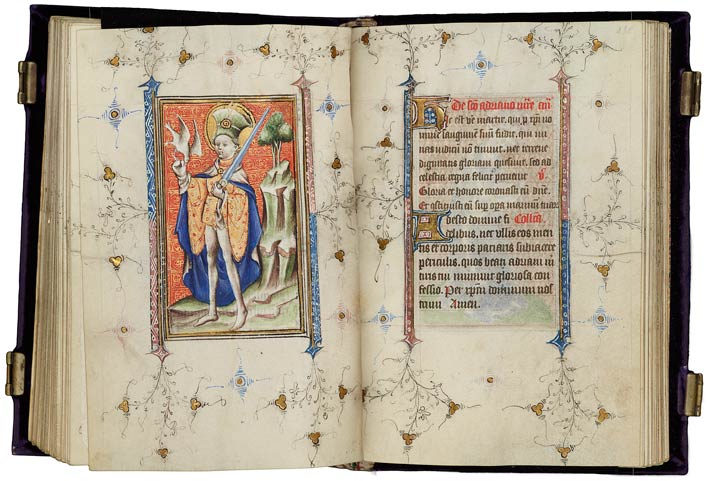

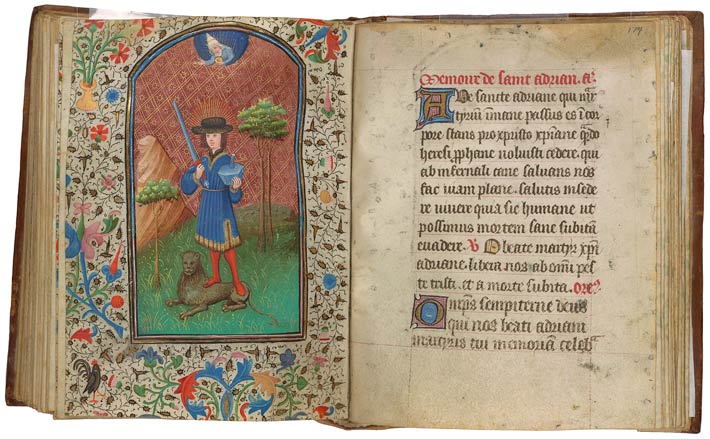

St. Adrian as a Fashion Plate (Part 1)

Book of Hours, in Latin

Illuminated by the Master of the Morgan Infancy Cycle

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1953

Adrian was a fourth-century pagan soldier before his conversion to Christianity, for which he was promptly martyred. Even by the standards of that era, his death was particularly brutal: his bones were crushed and his hands and head severed. In heaven his body — and his clothes — are resplendently restored. He wears a short embroidered pourpoint with luxurious poke sleeves. From his shoulders flows a long blue-lined cloak pinned at his throat with a gold morse. Chaussembles cover his lean legs and pointed feet, and he is crowned with a towering bonnet bedecked by a jeweled brooch with two feathers.

Luxury in a Time of Madness

In 1392 King Charles VI suffered the first of forty-four bouts of madness that would cripple his reign. During a lull in the Hundred Years' War, strife between France and Burgundy erupted into civil war. This domestic crisis was sparked by the 1407 assassination of Charles's brother by Duke John of Burgundy. In 1419 the duke, in turn, was murdered by supporters of the crown. During these tumultuous times, fashion reached unbelievable heights of luxury.

Men's and women's fashions were dominated by a new garment, the houpeland. Men's houpelands featured enormous sleeves and a skirt ranging from full length to crotch level. The pourpoint remained popular, albeit often finely embroidered and equipped with large sleeves. Accessories included fancy baldricks (sashes) and belts—both sometimes hung with bells. Tall bonnets or chaperons, often tied into imaginative shapes, completed the look.

Women's houpelands were always full length, with bombard or straight sleeves. The simpler cote hardy, with its voluminous skirt and tight upper body, continued to be worn. Women began to wear their hair in temples, a double-horned coif surmounted by veils or a tubular burlet.

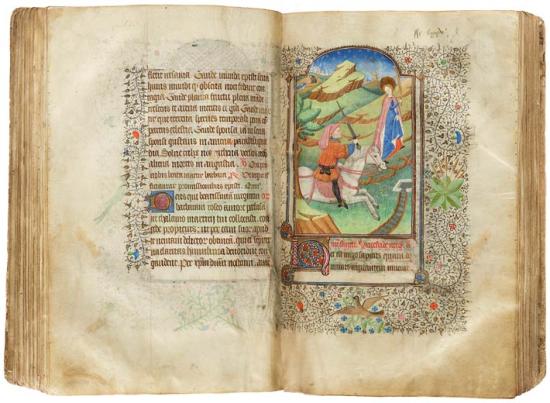

The Terrible Twenties

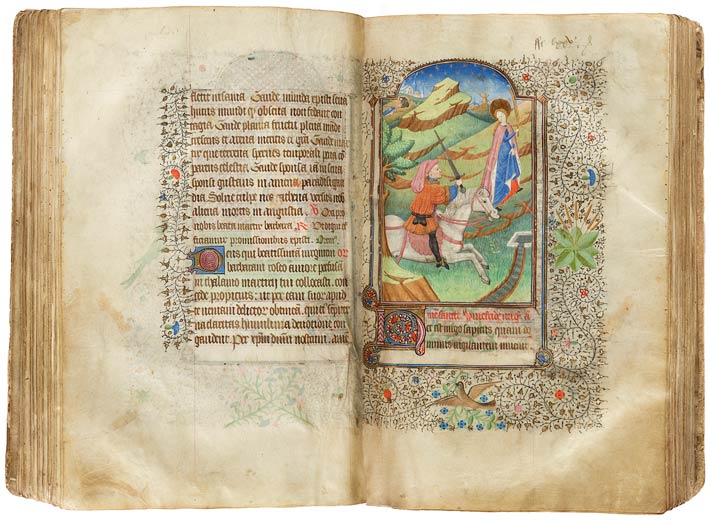

Hours of William Porter, in Latin

Illuminated by the Fastolf Master

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Jilted Suitor in a Murderous Rage

Sir William Porter, part of the English occupying force in France in the 1420s, commissioned this manuscript while in Rouen — hence the inclusion of a prayer to Winifred, a seventh-century Welsh saint venerated in England. When Winifred refused the chieftain Caradoc's proposal of marriage, the enraged young man pursued and decapitated the maiden. (Her miraculous restoration appears in the background.) Caradoc wears a new garment that evolved from the houpeland: a robe (gown). Short, unwaisted, but belted at the hips, the gown presents an unflatteringly bulbous silhouette. Also bulbous are his sleeves, large "bag hat," and gipser (purse).

The Terrible Twenties

Following the assassination of his father in 1419, the new duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, sided with England in one of the direst chapters of the Hundred Years' War. By 1422 northern France and Aquitaine were under English or Burgundian control. Paris was an occupied city. Only in 1429 did the tide begin to turn in France's favor, when Joan of Arc delivered Orléans and Charles VII was crowned king in Rheims Cathedral. Fashion retrenched.

While men and women continued to wear the houpeland, simpler garments for both sexes emerged. Men wore what was called a gown: a short, unwaisted garment unflatteringly belted at the hips. The resulting silhouette was top-heavy and bulbous. Sleeves were baggy, and the "bag hat" got droopier.

Women, while not dressed in the houpeland, might wear their new garment, also called a gown. Structured like the traditional cote hardy with a large skirt, the gown had an open or V neck and columnar or puffed sleeves. Headgear, however, did evolve: temples grew wider, and the veils and burlet worn atop them got taller.

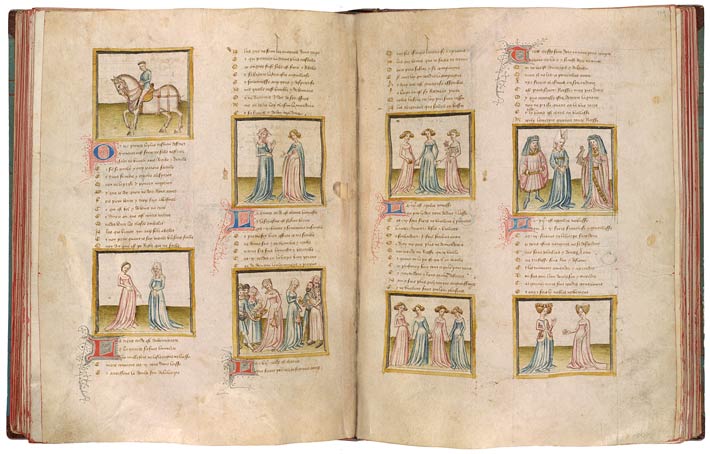

Women Dress Down

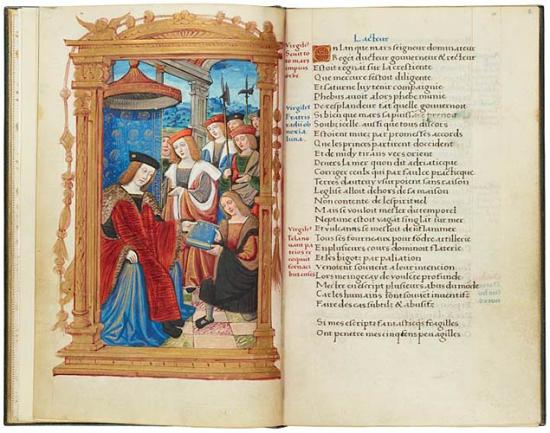

Poems, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Machaut's poem "Tale of the Harp" is peopled by such personifications as Meekness, Honesty, and Youth. While women in the 1420s wore houpelands, they also dressed in a new, simpler garment called a gown, which, as seen here, was similar to the traditional cote hardy. Only the woman at the lower right wears an old-fashioned open surcot; she is Nobility, and, indeed, royal women still wore this garment for ceremonies. The miniatures reveal a variety of women's headgear. These range from simple veils, to chaperons, to elegant temples — worn alone, with sailing veils, or with a burlet. The two men at right wear traditional houpelands.

The Terrible Twenties

Following the assassination of his father in 1419, the new duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, sided with England in one of the direst chapters of the Hundred Years' War. By 1422 northern France and Aquitaine were under English or Burgundian control. Paris was an occupied city. Only in 1429 did the tide begin to turn in France's favor, when Joan of Arc delivered Orléans and Charles VII was crowned king in Rheims Cathedral. Fashion retrenched.

While men and women continued to wear the houpeland, simpler garments for both sexes emerged. Men wore what was called a gown: a short, unwaisted garment unflatteringly belted at the hips. The resulting silhouette was top-heavy and bulbous. Sleeves were baggy, and the "bag hat" got droopier.

Women, while not dressed in the houpeland, might wear their new garment, also called a gown. Structured like the traditional cote hardy with a large skirt, the gown had an open or V neck and columnar or puffed sleeves. Headgear, however, did evolve: temples grew wider, and the veils and burlet worn atop them got taller.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

Hours of Catherine of Cleves, in Latin

Illuminated by the eponymous Master of Catherine of Cleves

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund and with the assistance of the Fellows

Catherine of Cleves Shows Off

Although duchess of Guelders, in the northern Netherlands, Catherine was also the niece of Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy. For reasons of culture — and snobbery — she leaned toward the duchy of her famous uncle with its opulent court and extravagant clothes. In this portrait, Catherine, while humbly distributing alms, could not be more richly attired. Her voluminous ermine-lined houpeland, with cascading bombard sleeves, harks back to the luxurious early decades of the century. Her hair is enmeshed in reticulated gold temples. The boy receiving her coin is dressed in a hand-me- down, a handsomely tailored gown once owned by a wealthy man.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

St. Adrian as a Fashion Plate (Part 2)

Book of Hours, in Latin and French

Illuminated by a Master of the Gold Scrolls

Gift of Julia Parker Wightman, 1993

That artists kept the clothing they depicted in their illuminations current is confirmed by comparing this Adrian with the one exhibited in Section 3. Here the saint is also well-attired, albeit in styles from around 1440. He wears a fur-lined, knee-length gown that is belted at the waist. The regular pleating and the slightly opened V neck, above which juts the collar of his doublet, are new features of the tailoring. Also new is his fur hat with its round crown and wide brim. Adrian's attributes include the anvil and hammer that were used to break his bones.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

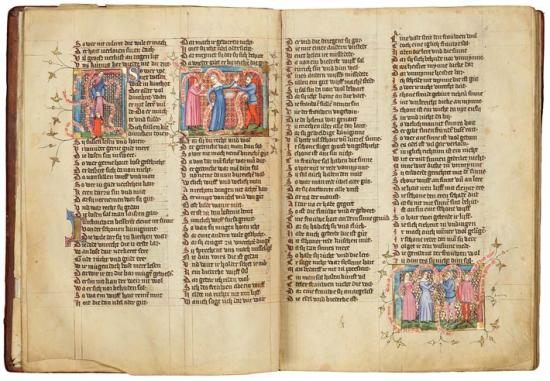

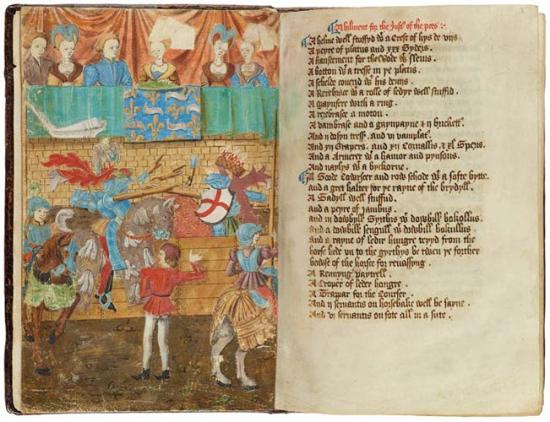

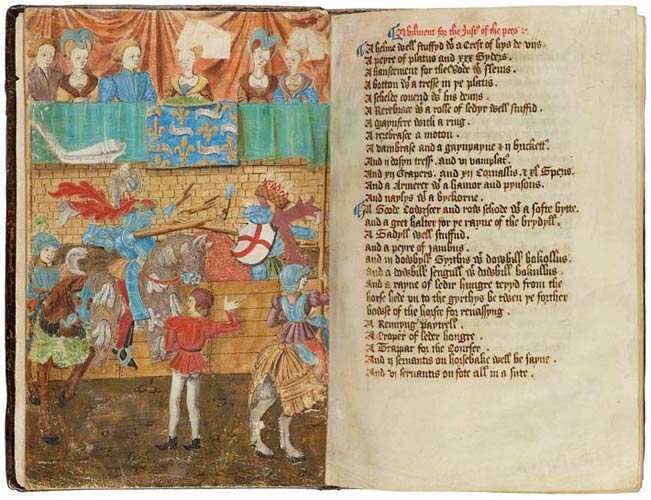

Women's Headgear Achieves New Heights

Ordinances of Chivalry, in English and Latin

Purchased, 1931

These men and women seated in a viewing stand watch a joust (in which lances are violently breaking). The two men wear the short gown — as does the squire in red in the foreground — with narrow pleats and raised shoulders. The muscular look is achieved by mahewters, padded rolls that enlarge the upper arms. Women wear fashionable gowns with wide V necks and partlets covering the bosom. (In addition, two of the women cover their fronts with fine linen.) Atop their temples two women wear thick V-shaped burlets, while the other two have butterfly veils that, supported by wires, sail high above their heads.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

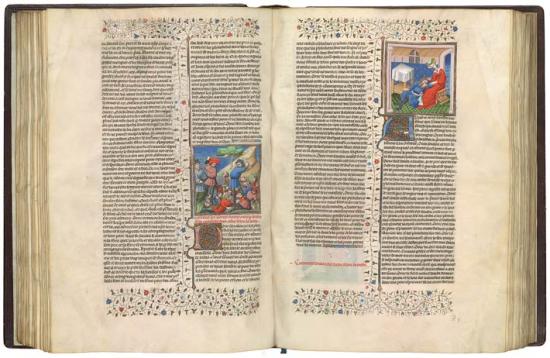

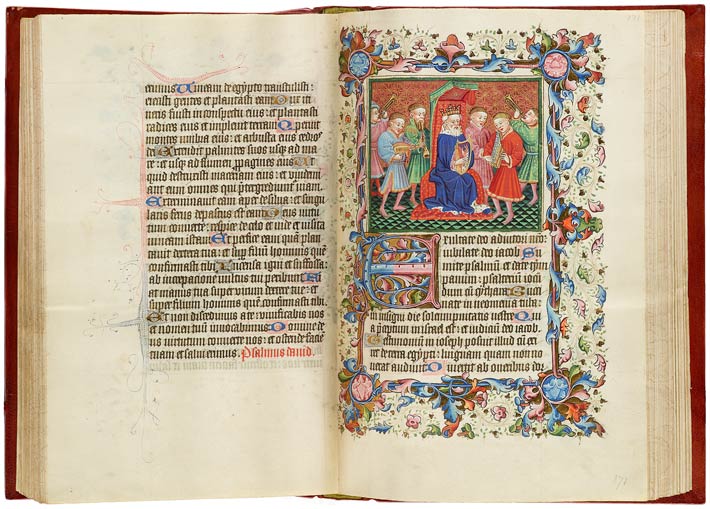

Musicians Have Always Been Snappy Dressers

Warwick Psalter-Hours, in Latin

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, with the assistance of the Fellows, and the special assistance of the Hon. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Murray Crane, Mr. Childs Frick, Mr. William S. Glazier, Mrs. Matilda Geddings Gray, Mr. Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Donald F. Hyde, Mr. Milton McGreevy, Colonel David McC. McKell, Mr. Joseph V. Reed, Mrs. Landon K. Thorne, Mr. Ralph Walker, Mr. Christian A. Zabriskie, and an anonymous foundation, 1958

Psalm 80 in medieval Psalters was traditionally illustrated with an image of David playing the harp. In this prayer book, a group of young men — all fashionably attired — joins the king in making music with a variety of instruments. They wear the knee-length, fur-lined gown, belted at the waist and with a full or slit skirt. Pleats at the skirt, bodice, and upper sleeves make the garment quite ample. The man's gown evolves quickly: the skirt gets shorter and the shoulders get wider. The musicians sport the bowl haircut called a "not heed."

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

St. Julian Accidentally Kills His Parents

Golden Legend, in French

Illuminated by the Sapience Master

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Julian slew his wife and her lover in bed, only to discover later that the people he killed were actually his parents. The saint is dressed in a man's elegant gown. Below a cinched waist, the gown flares into a skirt so short it barely covers his buttocks. Above the waist the gown expands, accentuating the torso. Tight pleats, gathered at the front and back, flatter the swelling forms of chest, back, and buttocks. Together, the pleats and padded shoulders create the flattering V shape of the masculine silhouette. Tall boots and slit sleeves accent the lean look.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

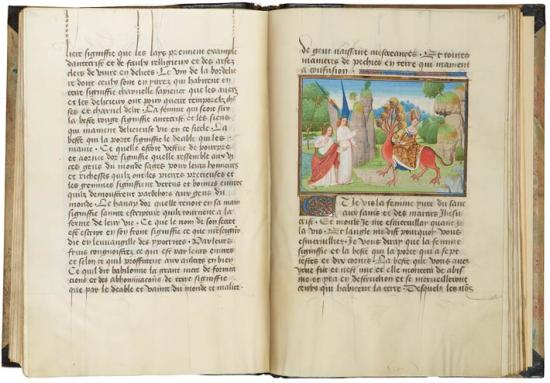

The Whore of Babylon Dresses the Part

Epistolary and Apocalypse of Charles the Bold, in French

Illuminated by Loyset Liédet and his workshop

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1905

Dressed extravagantly in scarlet cloth of gold, the Whore of Babylon rides the seven-headed beast. Although this manuscript was created around 1470, the Whore's headgear dates to the 1450s. Atop toweringly tall reticulated temples rests the thick rolls of a V-shaped burlet, behind which fall the dags of what was originally the burlet's cape. This headgear can go no further: it is as tall — and its burlet as close together — as can be. By 1470 it was seen as not just old-fashioned, but also decadent. (The styling of the Whore's gown, however, is characteristic of the period around 1470.)

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

St. Eugenia's Clothes Are Encoded

Golden Legend, in French

Illuminated by the Master of the Jardin de vertueuse consolation

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

SS. Protus and Hyacintus wear the full-length version of the man's gown — an alternate garment often preferred by middle-aged or older men. Above a full skirt, the torso was the same as with the short gown: pleats and padded shoulders formed a flattering male silhouette. Eugenia's attire, however, is anachronistic: the low wide neck and tippets hanging from her sleeves hark back to the fourteenth century. Her bejeweled turban (like that worn by the Roman emperor at the right) is complete fantasy. The illuminator used out-of-date and invented garments to place the martyrdom in a distant time and place, third-century Rome.

Peacocks of the Midcentury

In 1435, during the final chapter of the Hundred Years' War, Duke Philip the Good switched sides and supported King Charles VII. By the following year, the English occupation of Paris ended. When Charles VII regained Normandy and Aquitaine in 1453, the long war was finally over. In the ensuing period of peace and prosperity, fashion revived.

These decades saw the last of the houpeland. It continued to be worn by men and women in provincial areas, but in France and Flanders it was appropriate only for formal occasions. Men more often wore the gown: full or knee length, belted at the waist. Over the course of these thirty years, men's gowns, via flaring pleats and ample shoulder padding, assumed a flattering, V-shaped silhouette. While the chaperon remained popular, new hats also arrived.

Women's gowns featured wide V necks with contrasting collars and partlets (plackards worn at the midriff). Headgear atop the temples continued to evolve, growing ever more extravagant. Burlets got thicker and climbed higher. Butterfly veils, supported by wires, floated like sails above ladies' heads.

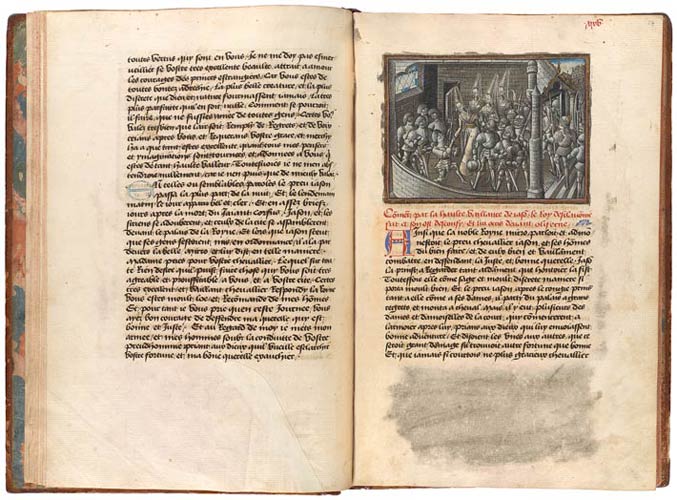

Late Gothic Vertigo

History of Jason, in French

Illuminated in the style of the Master of the Champion des Dames

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1902

Women's Headgear Reaches Its Climax

The look for women in the 1460s and '70s was defined by the turret. In French this headgear was called a haut bonnet (high bonnet) or mitre (after the bishop's ceremonial miter). An attenuated cone, the turret was normally worn with wafting transparent veils. As seen in the miniature here, it was sometimes the custom for these veils to fall below the eyes. The turret was affixed to the head via the templet, a cloth or metal base. At the bottom of each turret shown here is a small hoop: this is the visible part of the templet to which the turret is anchored.

Late Gothic Vertigo

In the 1460s and '70s fashions reached their Gothic climax. The look for both men and women was tall, long, and lean. Thin was in.

The look for men was dominated by the gown, worn either very short (to the crotch—or barely so) or very long (to the ground). Both versions, accented by a thin belt around a narrow waist, featured high padded shoulders and pleats that flared down over the buttocks and up over the back and chest. These features, developed during the previous decades, brought to a culmination the flatteringly masculine V-shaped silhouette. Pouleines, which accented the lean look, were revived. The chaperon, in fashion for over a hundred years, finally went out of style as new hats–especially a tall, loaf-shaped version—arrived.

Women's gowns continued with their wide V necks, high wasp waist, and long trains. For headgear, temples went out of fashion and were replaced by the turret. This cone-shaped coif, from the tip of which cascaded transparent veils, is perhaps the stereotypical ladies' hat from the late Middle Ages.

Geneviève: The Period's Poster Girl

Romance of Tristan, in French

Illuminated by the Master of the Vienna Mamerot

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1903

Geneviève, receiving King Mark's letter, exemplifies this period's look. Her turret, from which cascades a transparent veil, terminates upon a frontlet, a wide band of cloth that frames her face. (The frontlet would play an important role over the next decades.) Her wide, V-necked gown has a high, narrow waist and tight sleeves with funnel cuffs. Black, a popular color at this time, accents her turret and frontlet, collar, cuffs, and wide hem. The distinctive feature of men's clothing here is the revival of pouleines.

Late Gothic Vertigo

In the 1460s and '70s fashions reached their Gothic climax. The look for both men and women was tall, long, and lean. Thin was in.

The look for men was dominated by the gown, worn either very short (to the crotch—or barely so) or very long (to the ground). Both versions, accented by a thin belt around a narrow waist, featured high padded shoulders and pleats that flared down over the buttocks and up over the back and chest. These features, developed during the previous decades, brought to a culmination the flatteringly masculine V-shaped silhouette. Pouleines, which accented the lean look, were revived. The chaperon, in fashion for over a hundred years, finally went out of style as new hats–especially a tall, loaf-shaped version—arrived.

Women's gowns continued with their wide V necks, high wasp waist, and long trains. For headgear, temples went out of fashion and were replaced by the turret. This cone-shaped coif, from the tip of which cascaded transparent veils, is perhaps the stereotypical ladies' hat from the late Middle Ages.

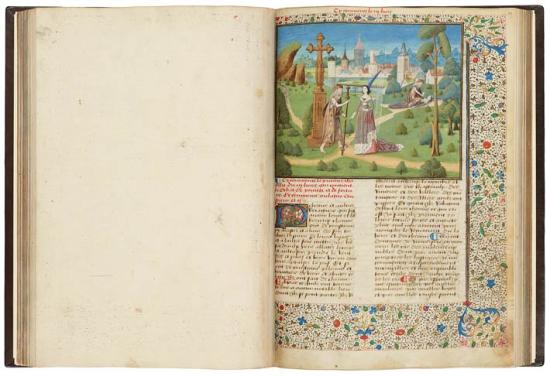

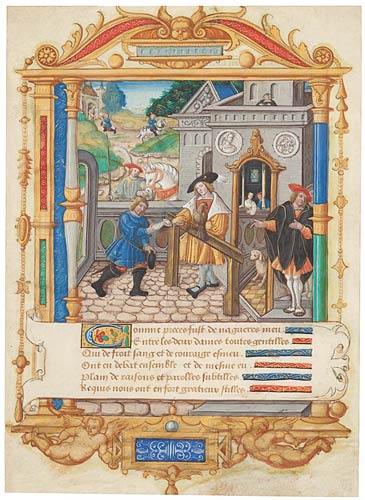

Catfight at the Crossroads

Of Noble Men and Women, in French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1908

Boccaccio's works were popular in France, appearing in translation in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In the miniature shown here, personifications of Fortune and Poverty meet at a crossroads. Poverty, dressed like a poor pilgrim in ragged clothes, has a walking stick and a hat to which are affixed badges of the shrines she has visited. Fortune is dressed to the nines. Her turret, anchored to her face with a black frontlet, is vertiginously tall. Her narrow-waisted, V-necked gown features ermine at the collar, cuffs, and wide hem. As seen in the right background, the meeting ends poorly.

Late Gothic Vertigo

In the 1460s and '70s fashions reached their Gothic climax. The look for both men and women was tall, long, and lean. Thin was in.

The look for men was dominated by the gown, worn either very short (to the crotch—or barely so) or very long (to the ground). Both versions, accented by a thin belt around a narrow waist, featured high padded shoulders and pleats that flared down over the buttocks and up over the back and chest. These features, developed during the previous decades, brought to a culmination the flatteringly masculine V-shaped silhouette. Pouleines, which accented the lean look, were revived. The chaperon, in fashion for over a hundred years, finally went out of style as new hats–especially a tall, loaf-shaped version—arrived.

Women's gowns continued with their wide V necks, high wasp waist, and long trains. For headgear, temples went out of fashion and were replaced by the turret. This cone-shaped coif, from the tip of which cascaded transparent veils, is perhaps the stereotypical ladies' hat from the late Middle Ages.

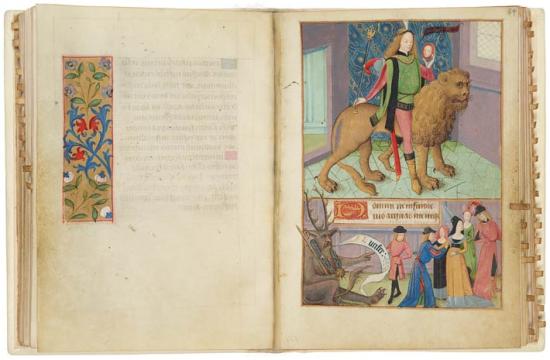

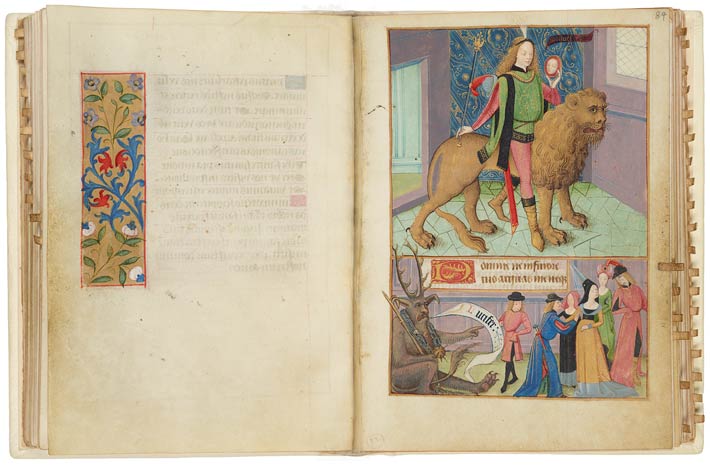

Personification of Pride

Book of Hours, in Latin

Illuminated by Robinet Testard

Purchased through the Fellows Fund, 1979

Each of this prayer book's Penitential Psalms is illustrated with a personification of a sin to be avoided. The series begins with the first of all sins, Pride, who rides a lion while admiring himself in a mirror. He wears an embroidered green gown with slit sleeves and, under that, a red velvet doublet. His accessories include a headband (with feather), necklace, and studded belt. Thrown over his right shoulder is the black cornet attached to a small gray hat that falls down his back. In the bottom border, Lucifer encourages people to engage in arrogant and pompous behavior.

Late Gothic Vertigo

In the 1460s and '70s fashions reached their Gothic climax. The look for both men and women was tall, long, and lean. Thin was in.

The look for men was dominated by the gown, worn either very short (to the crotch—or barely so) or very long (to the ground). Both versions, accented by a thin belt around a narrow waist, featured high padded shoulders and pleats that flared down over the buttocks and up over the back and chest. These features, developed during the previous decades, brought to a culmination the flatteringly masculine V-shaped silhouette. Pouleines, which accented the lean look, were revived. The chaperon, in fashion for over a hundred years, finally went out of style as new hats–especially a tall, loaf-shaped version—arrived.

Women's gowns continued with their wide V necks, high wasp waist, and long trains. For headgear, temples went out of fashion and were replaced by the turret. This cone-shaped coif, from the tip of which cascaded transparent veils, is perhaps the stereotypical ladies' hat from the late Middle Ages.

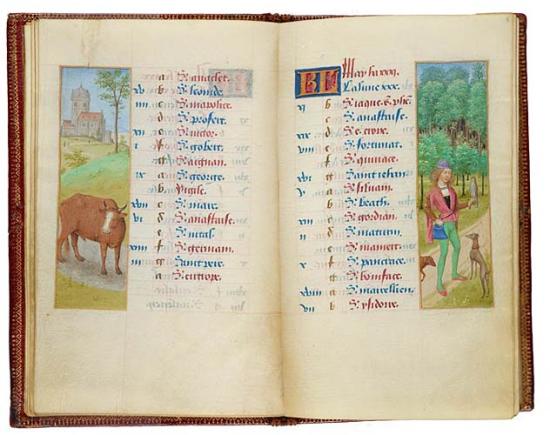

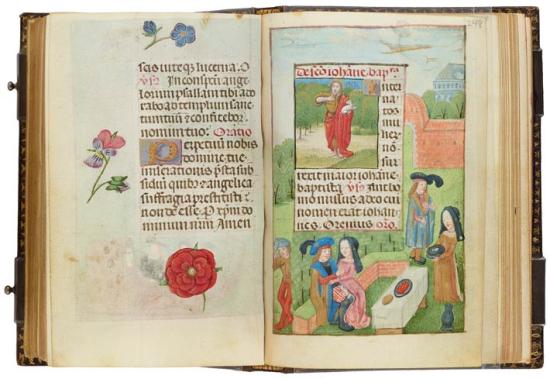

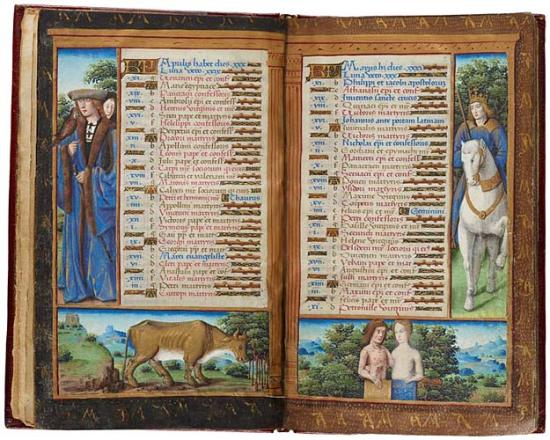

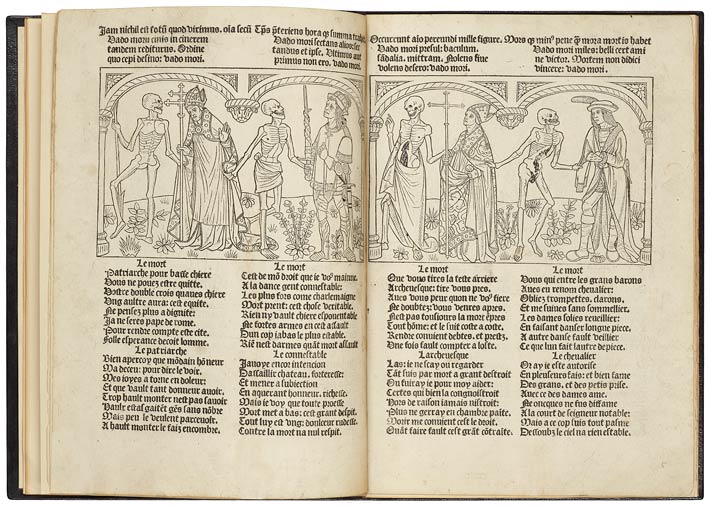

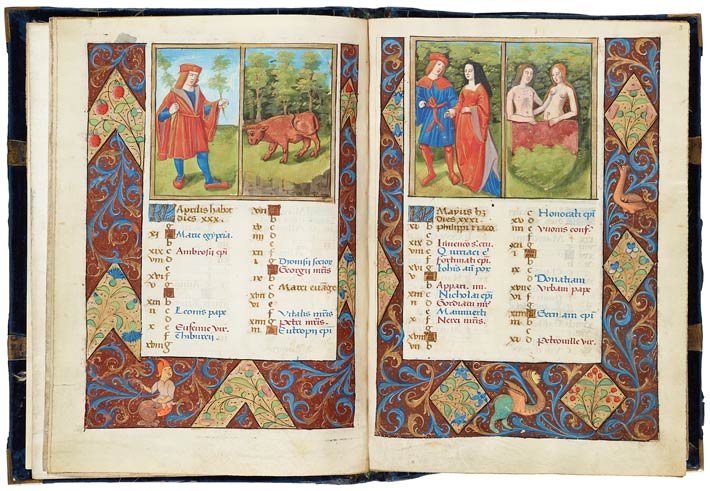

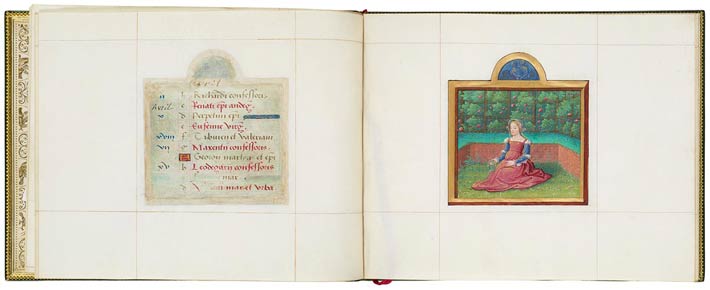

A Fop Goes Hawking (Part 1)

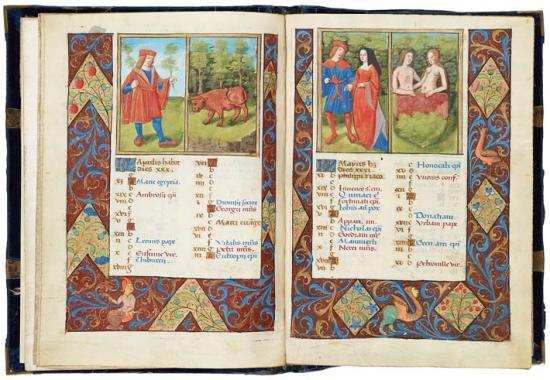

Book of Hours, in Latin and French

Illuminated by Simon Marmion

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1900

Calendars in prayer books are often excellent sources for depictions of contemporaneous clothing. The month of May, shown here on the right, is illustrated by the leisurely occupation of hawking. The youth wears a gown with slit sleeves and a skirt so short it no longer covers his crotch. The tan sleeves and black front of his doublet and, at his neck, the top of his linen shirt are all visible. The lilac of his hat and pink of his shoes were favorite colors of the illuminator, Simon Marmion. (On the left is Taurus, the zodiacal sign for the month of April.)

Late Gothic Vertigo

In the 1460s and '70s fashions reached their Gothic climax. The look for both men and women was tall, long, and lean. Thin was in.

The look for men was dominated by the gown, worn either very short (to the crotch—or barely so) or very long (to the ground). Both versions, accented by a thin belt around a narrow waist, featured high padded shoulders and pleats that flared down over the buttocks and up over the back and chest. These features, developed during the previous decades, brought to a culmination the flatteringly masculine V-shaped silhouette. Pouleines, which accented the lean look, were revived. The chaperon, in fashion for over a hundred years, finally went out of style as new hats–especially a tall, loaf-shaped version—arrived.

Women's gowns continued with their wide V necks, high wasp waist, and long trains. For headgear, temples went out of fashion and were replaced by the turret. This cone-shaped coif, from the tip of which cascaded transparent veils, is perhaps the stereotypical ladies' hat from the late Middle Ages.

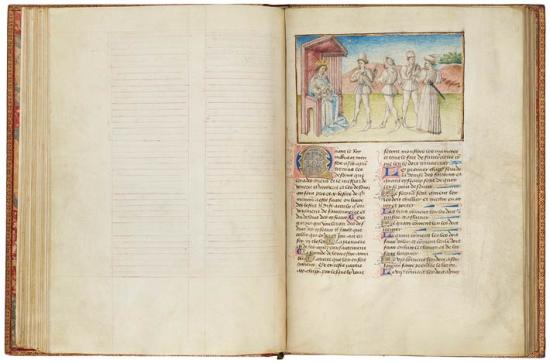

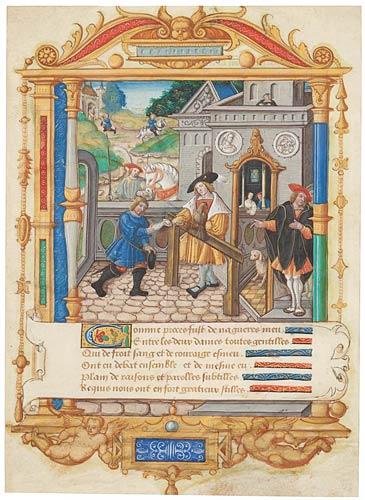

Pinnacle of the V-Shaped Silhouette for Men

Livre du roy Modus et de la royne Racio

Illuminated by the Master of the Vienna Roman de la rose (Jean Hortart?)

Purchased, 1947

Ferrières's treatise on hunting is open to the chapter on falconry, illustrated with an enthroned King Modus instructing youths in the art of hunting with birds. The pen-and-wash medium carefully delineates the tailoring of their garments. Three young men wear the short gown with pleating that flares flatteringly both below and above the narrow waist. The slit sleeves are highly padded at the shoulders. While the youths sport the revived pouleines, two also wear loaf-shaped caps, typical of the 1460s. The hunter at right, who prefers the long gown, wears a "burlet-chaperon," headgear in which the fat burlet is permanently rolled.

Late Gothic Vertigo

In the 1460s and '70s fashions reached their Gothic climax. The look for both men and women was tall, long, and lean. Thin was in.

The look for men was dominated by the gown, worn either very short (to the crotch—or barely so) or very long (to the ground). Both versions, accented by a thin belt around a narrow waist, featured high padded shoulders and pleats that flared down over the buttocks and up over the back and chest. These features, developed during the previous decades, brought to a culmination the flatteringly masculine V-shaped silhouette. Pouleines, which accented the lean look, were revived. The chaperon, in fashion for over a hundred years, finally went out of style as new hats–especially a tall, loaf-shaped version—arrived.

Women's gowns continued with their wide V necks, high wasp waist, and long trains. For headgear, temples went out of fashion and were replaced by the turret. This cone-shaped coif, from the tip of which cascaded transparent veils, is perhaps the stereotypical ladies' hat from the late Middle Ages.

Twilight of the Middle Ages

Bifolio inserted into a Book of Hours

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907

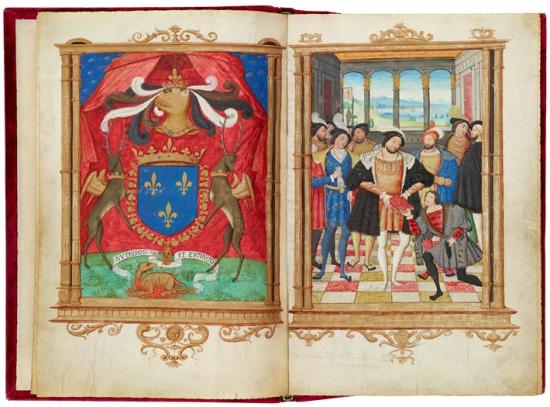

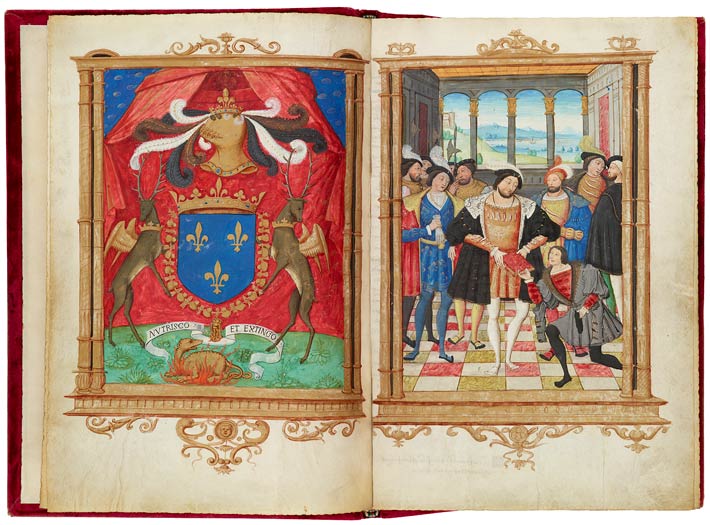

King Charles VIII in a New Look

The heraldry — which calls Charles VIII king of France, Sicily, and Jerusalem — dates this image of the kneeling monarch to the short period in which he ruled (at least titularly) those two far-flung realms. Charles wears a new garment, the sayon, a man's outer coat, often of luxurious cloth, with a fitted waist and a many-gored skirt. Its huge sleeves are typical of the 1490s. He is shod in new pantoffles, round-toed slippers (often with open backs). Before him lies the new carmignolle, a man's hat with a low crown and a divided brim held up by laces (of which the gold aglets are visible).

Twilight of the Middle Ages

This was a period of transition in northern Europe—the Middle Ages were not yet over, and the Renaissance had not yet begun. Both King Charles VIII and Louis XII invaded Italy, and these military campaigns exposed France to Italian art, culture, and fashion. At the same time, the Late Gothic style still dominated the arts—and clothing—of northern Europe. Fashions of this period reflect these conflicts.

In the 1480s, the look for men changed abruptly. Padded shoulders and the V-shaped silhouette disappeared. Long loose open gowns came into style and, by the 1490s, these gowns became especially voluminous and bulky. Round-toed shoes replaced the pointy pouleines. New, however, and probably reflecting Italian influence, were the man's outer coat called a sayon, the man's hat called a carmignolle, and doublets with slit sleeves through which the linen of the shirt protruded.

Women's gowns of this period also became fuller, and bombard sleeves were revived. The neck got square. The turret disappeared, while its frontlet remained, now attached to a new small-crowned coif.

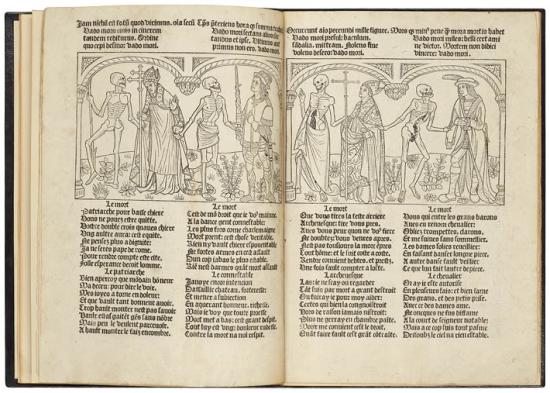

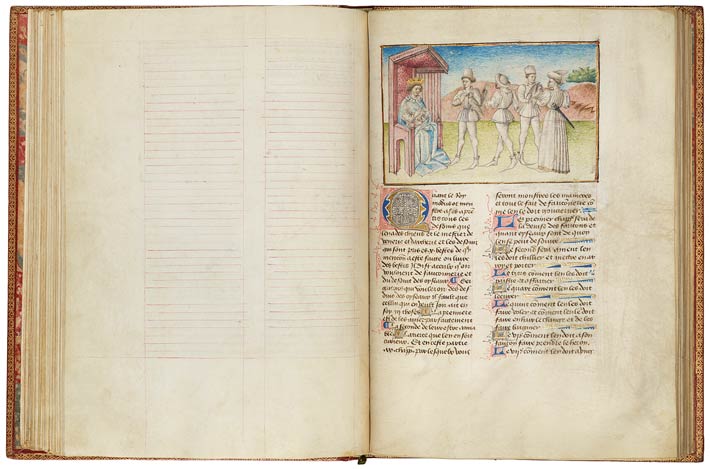

Death Takes a Knight

Dance of Death, in French

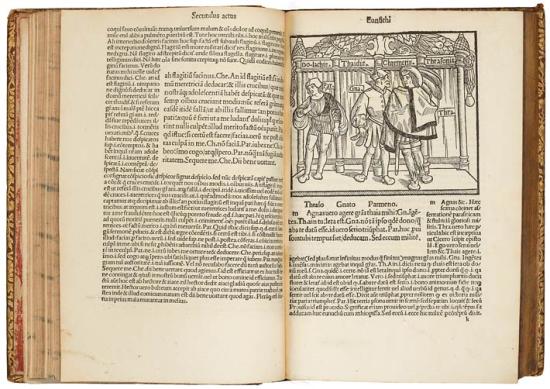

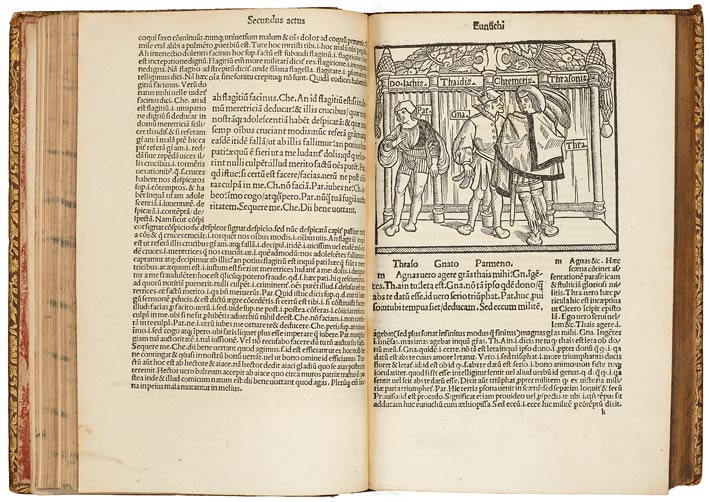

Woodcuts designed by the Master of the Chronique scandaleuse(?)

Purchased, 1975

For our purposes, we can ignore the patriarch, the constable, and the archbishop (Death's first three victims) and concentrate on the knight at the far right. His gown has the new look of the 1480s. Open, with wide lapels, it is long, loose, and, lacking the pleats of the previous decades, hides, rather than highlights, the male form. Gone, too, are the flattering padded shoulders. His hat, with its low crown and brim, is also new, as are his shoes. These are the demy pantouffles, round-toed slippers with an open back.

Twilight of the Middle Ages

This was a period of transition in northern Europe—the Middle Ages were not yet over, and the Renaissance had not yet begun. Both King Charles VIII and Louis XII invaded Italy, and these military campaigns exposed France to Italian art, culture, and fashion. At the same time, the Late Gothic style still dominated the arts—and clothing—of northern Europe. Fashions of this period reflect these conflicts.

In the 1480s, the look for men changed abruptly. Padded shoulders and the V-shaped silhouette disappeared. Long loose open gowns came into style and, by the 1490s, these gowns became especially voluminous and bulky. Round-toed shoes replaced the pointy pouleines. New, however, and probably reflecting Italian influence, were the man's outer coat called a sayon, the man's hat called a carmignolle, and doublets with slit sleeves through which the linen of the shirt protruded.

Women's gowns of this period also became fuller, and bombard sleeves were revived. The neck got square. The turret disappeared, while its frontlet remained, now attached to a new small-crowned coif.

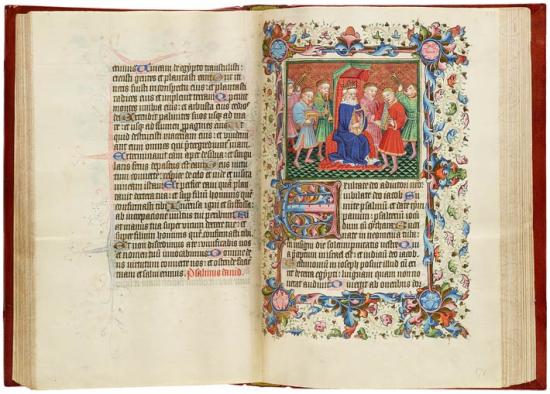

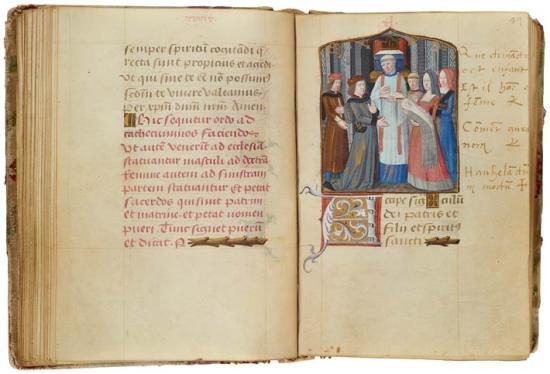

New Trends Reflected in a Bishop's Prayer Book

Pontifical, in Latin

Illuminated by the Master of Cardinal de Bourbon

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1908

The baptismal rite in this Pontifical (a liturgical service book used by a bishop) is illustrated by a baptism scene with people dressed in contemporaneous fashions. Thus the godfather in gray and, behind him, the father in brown wear the gown of the 1480s that is loose, without the flaring pleats popular during the previous decades. They both wear a hat with a low crown and a divided, upturned brim. Slung across each man's chest is a black cornet, which is attached to a fur hat falling down the back. The pink gown of the godmother has a new square neck.

Twilight of the Middle Ages

This was a period of transition in northern Europe—the Middle Ages were not yet over, and the Renaissance had not yet begun. Both King Charles VIII and Louis XII invaded Italy, and these military campaigns exposed France to Italian art, culture, and fashion. At the same time, the Late Gothic style still dominated the arts—and clothing—of northern Europe. Fashions of this period reflect these conflicts.

In the 1480s, the look for men changed abruptly. Padded shoulders and the V-shaped silhouette disappeared. Long loose open gowns came into style and, by the 1490s, these gowns became especially voluminous and bulky. Round-toed shoes replaced the pointy pouleines. New, however, and probably reflecting Italian influence, were the man's outer coat called a sayon, the man's hat called a carmignolle, and doublets with slit sleeves through which the linen of the shirt protruded.

Women's gowns of this period also became fuller, and bombard sleeves were revived. The neck got square. The turret disappeared, while its frontlet remained, now attached to a new small-crowned coif.

Striped Hose and Double Hats

Book of Hours, in Latin

Bequest of E. Clark Stillman, 1995

In addition to the flowers strewn on most of its leaves, this tiny prayer book also contains numerous borders historiated with people dressed in contemporaneous clothing. The two foppishly dressed men shown here wear the new loose calf-length gown with wide lapels and long slit sleeves. Each man also wears two hats: a large wide-brimmed version, with an ostrich feather, worn atilt over a small cap. The seated youth wears the new stocks divided into lower and upper hose (here the upper hose — the boulevars — are striped). The women wear a new low-crowned coif with wide frontlet.

Twilight of the Middle Ages

This was a period of transition in northern Europe—the Middle Ages were not yet over, and the Renaissance had not yet begun. Both King Charles VIII and Louis XII invaded Italy, and these military campaigns exposed France to Italian art, culture, and fashion. At the same time, the Late Gothic style still dominated the arts—and clothing—of northern Europe. Fashions of this period reflect these conflicts.

In the 1480s, the look for men changed abruptly. Padded shoulders and the V-shaped silhouette disappeared. Long loose open gowns came into style and, by the 1490s, these gowns became especially voluminous and bulky. Round-toed shoes replaced the pointy pouleines. New, however, and probably reflecting Italian influence, were the man's outer coat called a sayon, the man's hat called a carmignolle, and doublets with slit sleeves through which the linen of the shirt protruded.

Women's gowns of this period also became fuller, and bombard sleeves were revived. The neck got square. The turret disappeared, while its frontlet remained, now attached to a new small-crowned coif.

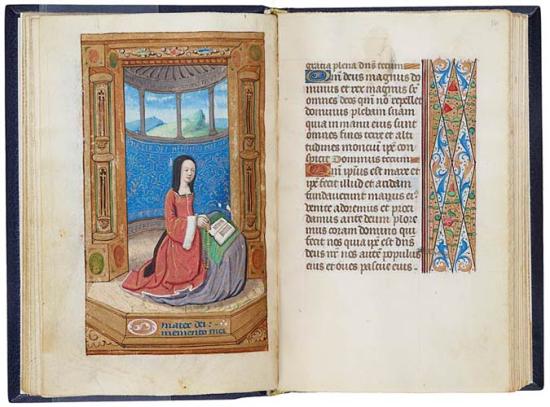

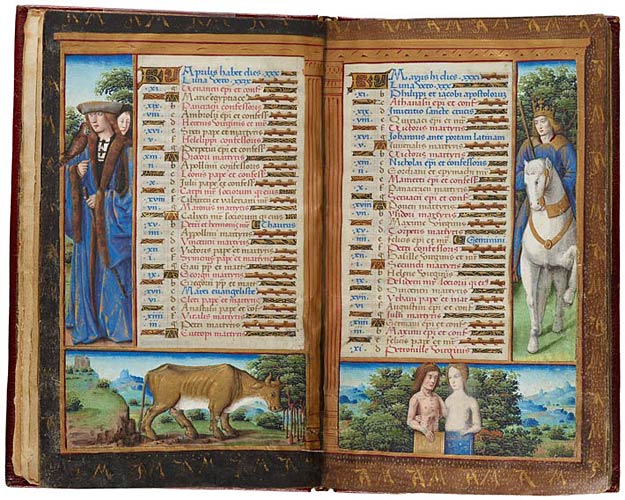

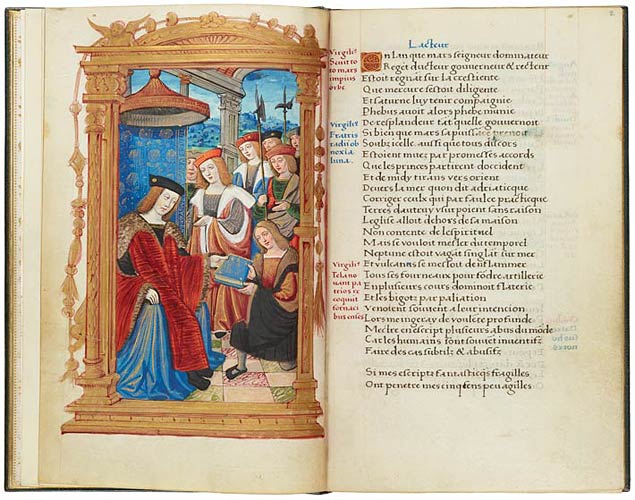

Portraits in Prayer Books

Book of Hours, in Latin and French

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Men and women who specially commissioned Books of Hours often asked that their portraits be included. The woman portrayed here originally faced an image of the Virgin Mary, which has since gone astray. Her fur-lined gown has the new square neck and small bombard sleeves. Her headgear is the new small-crowned coif with wide frontlet and an unusually long cornet trailing down her back. She prays from a rosary and a Book of Hours, the loose green chemise binding of which spreads like a place mat over the prie-dieu.

Twilight of the Middle Ages

This was a period of transition in northern Europe—the Middle Ages were not yet over, and the Renaissance had not yet begun. Both King Charles VIII and Louis XII invaded Italy, and these military campaigns exposed France to Italian art, culture, and fashion. At the same time, the Late Gothic style still dominated the arts—and clothing—of northern Europe. Fashions of this period reflect these conflicts.

In the 1480s, the look for men changed abruptly. Padded shoulders and the V-shaped silhouette disappeared. Long loose open gowns came into style and, by the 1490s, these gowns became especially voluminous and bulky. Round-toed shoes replaced the pointy pouleines. New, however, and probably reflecting Italian influence, were the man's outer coat called a sayon, the man's hat called a carmignolle, and doublets with slit sleeves through which the linen of the shirt protruded.