Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton

One day in Peking I was sitting on the main square drawing a chrysanthemum and a little boy stopped close, looked at what I was doing, and told his father: “Look, he is writing a chrysanthemum.” He was right. I am a writer.

—Rick Barton, as told to artist Etel Adnan

Little is known about Rick Barton (1928–1992), who, between 1958 and 1962, created hundreds of drawings of striking originality. His subjects range from the intimacy of his room to the architecture of Mexican cathedrals, and from the gathering places of Beat-era San Francisco to the sinuous contours of plants. Drawing almost exclusively in pen or brush and ink, he captured these themes in a web of line that evokes both drawing and writing. At times it was simple and economical, but more often it was complex and kaleidoscopic.

Most of the drawings on view were once part of printmaker Henry Evans’s personal collection of nearly eight hundred sheets by Barton, which Evans donated to the library at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1971. Thirteen years earlier, Barton had begun to produce linocut prints at Evans’s Peregrine Press, one of several small presses that emerged in the Bay Area in the 1950s. Evans became Barton’s champion and patron, furnishing him with art supplies and promoting his work. However, apart from small displays in cafés and bookshops in the 1950s and ’60s, this is the first time that Barton’s work is being seen by the public.

Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton is made possible by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Agnes Gund, Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin M. Rosen, the Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Research and Publications, and the Rita Markus Fund for Exhibitions, with support from The Lunder Foundation – Peter and Paula Lunder Family.

Overview

Gallery Images

Introduction

Richard William Barton (1928–1992) was born in New York City, and he grew up just a few blocks from the Morgan. A lifelong storyteller, Barton favored anecdotes that emphasize his hardscrabble childhood as a “dead-end kid.” Low on funds, and having completed only two years of high school, the budding artist embarked on an extensive self-guided education at the New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. At seventeen he enlisted in the US Navy, visiting China during his service. The primacy of line in traditional Chinese brush painting had an enduring impact on him.

Barton was discharged from the navy early, following a hospitalization that was likely related to mental illness; he described himself as paranoid psychotic. He relocated to the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-1950s, at the height of the Beat era. Two decades later, he moved to San Diego, where he remained until his death in 1992. In San Francisco, Barton appears to have intersected with less prominent Beat figures of the day, developing his own cohort of artists and interlocutors. But there are few records of his activities after the mid-1960s, and the life of this unusual artist largely remains a mystery.

Untitled [Self-portrait]

Among the nearly eight hundred drawings by Barton that reside at UCLA, this self-portrait stands out for its naturalistic style. Like the rest, however, it was collected by Henry Evans— an antiquarian book dealer, fine-art printer, publisher, and printmaker—between 1958 and 1962 and donated to the university in 1971. The inscription reads, “For Henry from Rick,” alluding to the close relationship between the artist and his patron.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Self-portrait], September 21, 1959

Charcoal

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

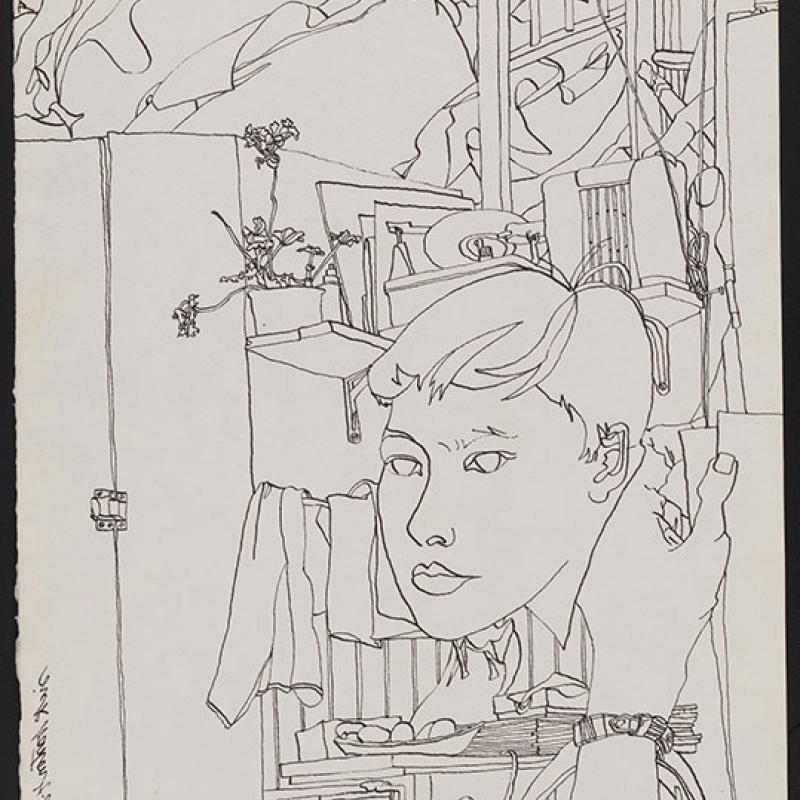

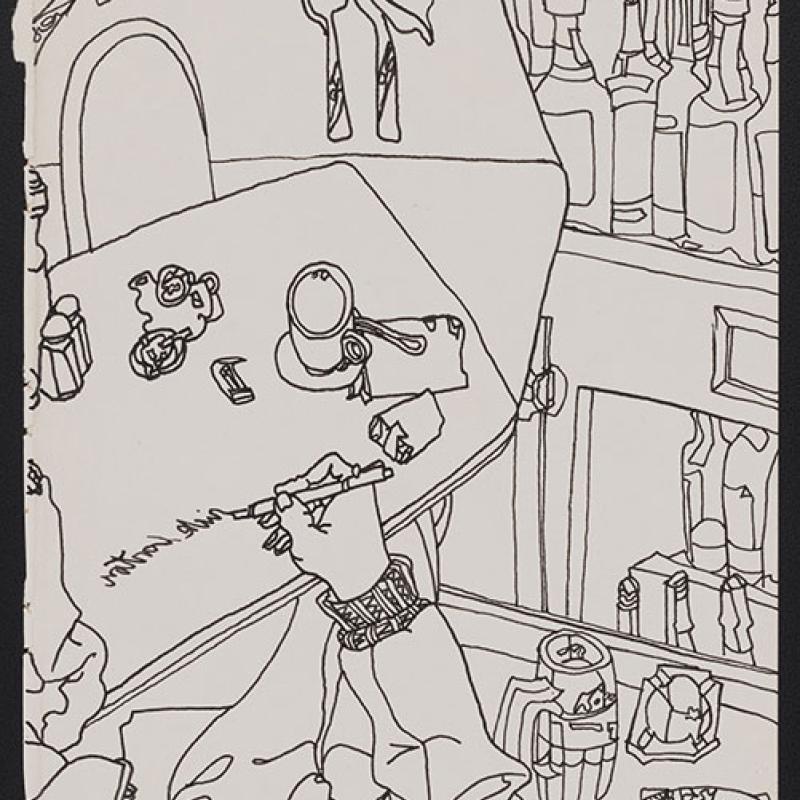

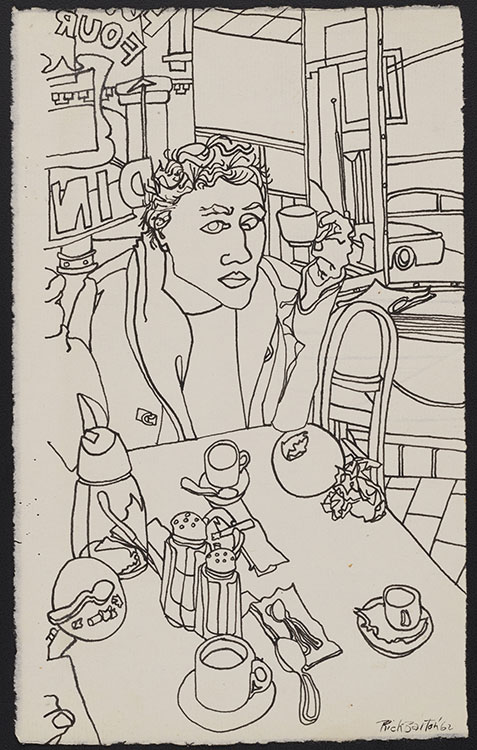

Untitled [Signature self-portrait]

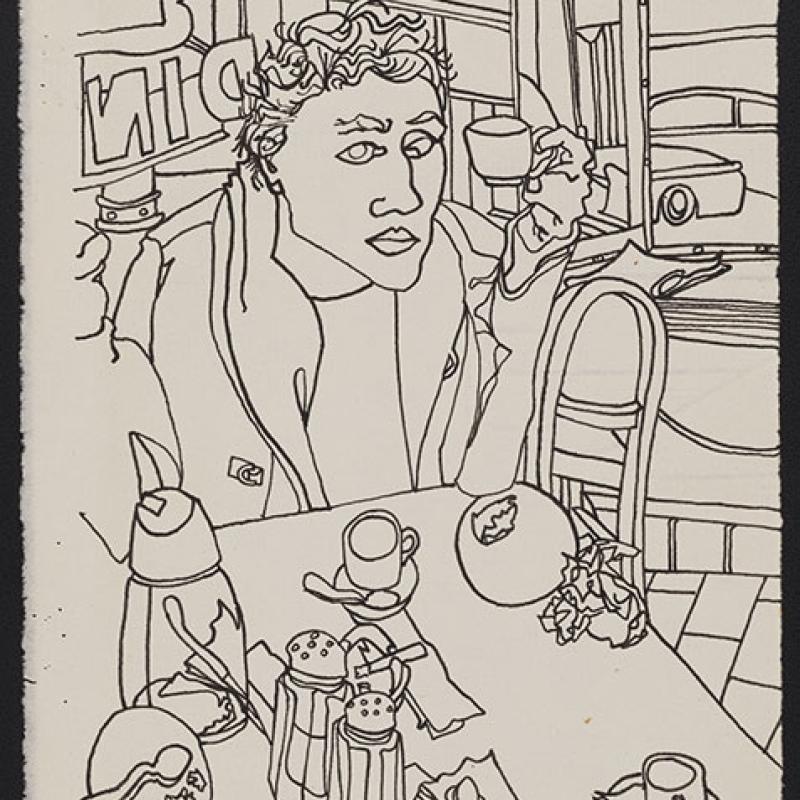

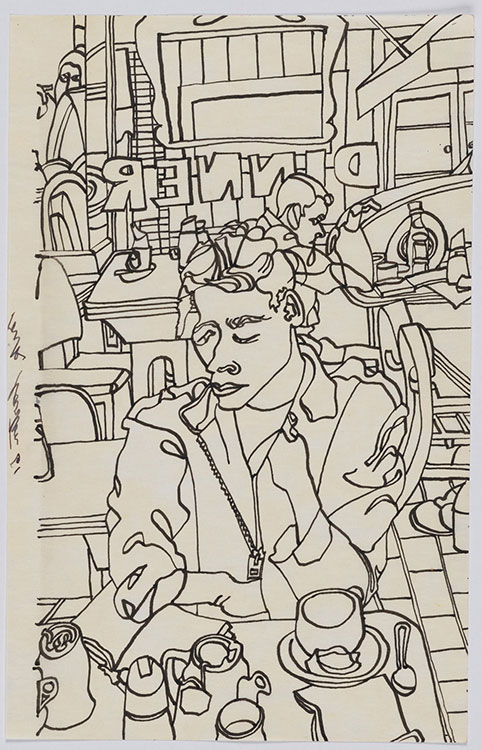

Compared to the charcoal sketch nearby, this drawing, which is also a self-portrait of sorts, is far more typical of Barton’s style. It shows the artist signing his name backward on a café table; his regular habit of mirror writing may have stemmed from his admiration for Leonardo da Vinci, whose use of reverse handwriting is widely known. Using a consistently weighted line that borders at times on cartoonish, Barton captured the minutiae of his environment— the zipper on his jacket, a beer mug, a coffee cup, ashtrays, his cigarette pack and matches—from an unstable and shifting perspective.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Signature self-portrait], 1961

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

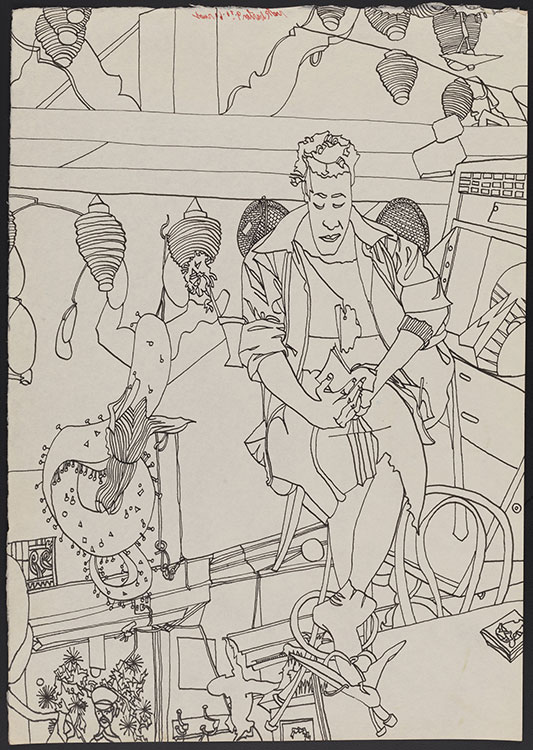

Untitled [Disarticulated draftsman]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Disarticulated draftsman], May 11, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

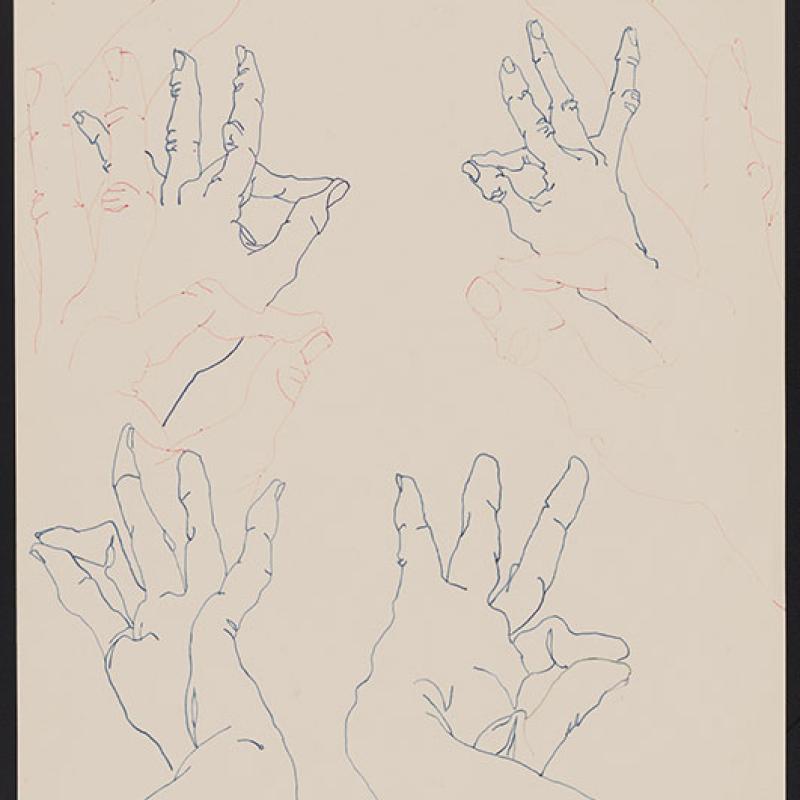

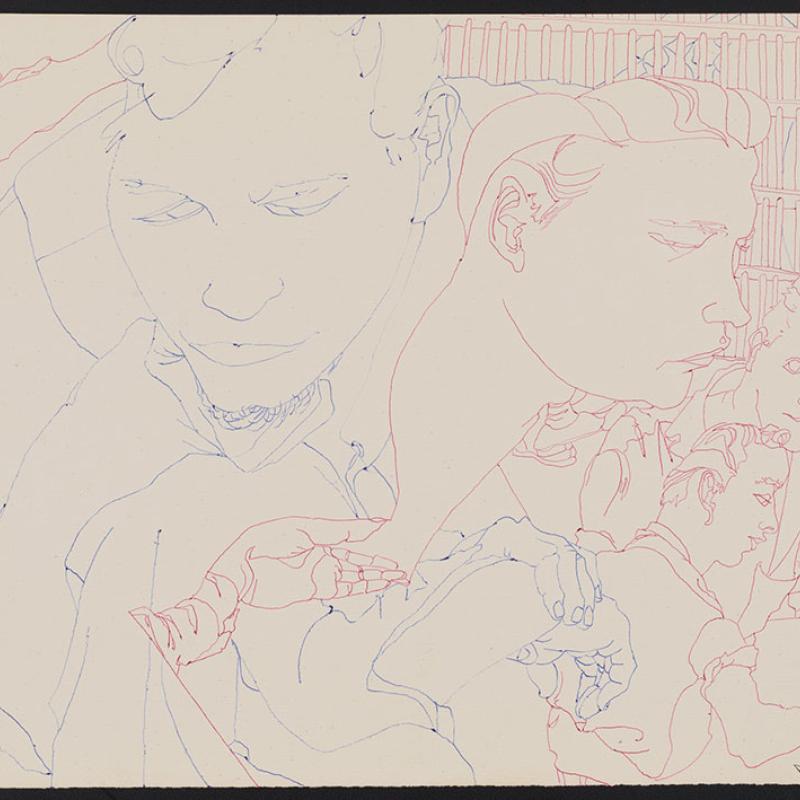

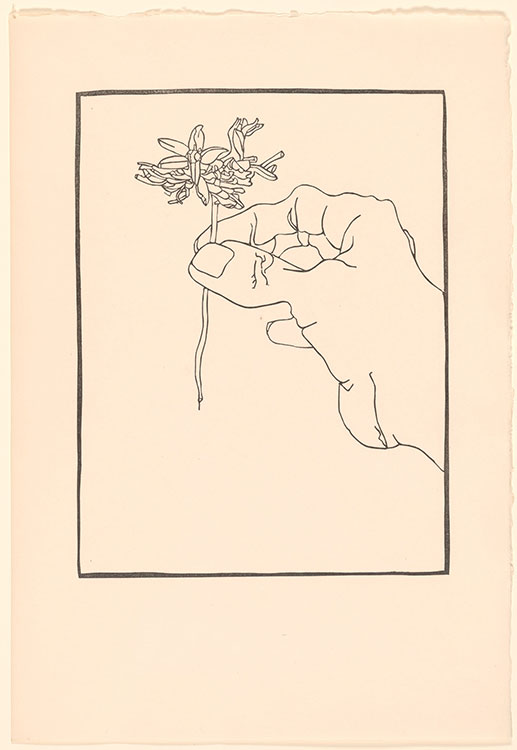

Untitled [Hands]

Hands, which are notoriously difficult to draw, frequently appear in Barton’s work. This sketch, possibly made while the artist was incarcerated, examines a specific gesture from multiple angles. The composition underscores the expressive potential of hands, and its overlapping of red and blue lines suggests movement.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Hands], 1959

Red and blue pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

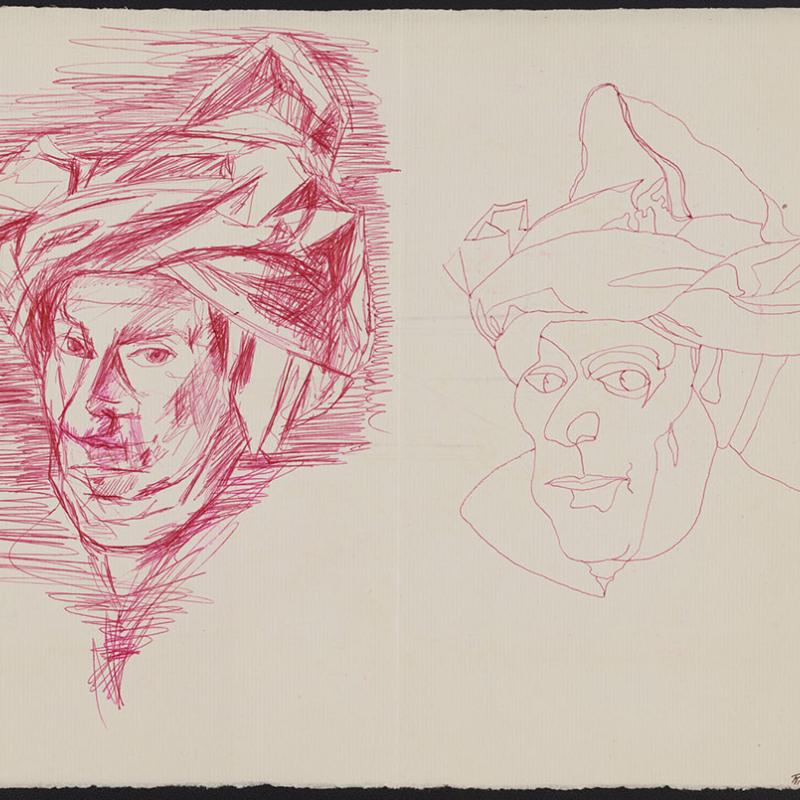

Untitled [After Jan van Eyck]

This drawing reveals Barton’s process of visual distillation. On the left side of a folded sheet, he copied a famous fifteenth-century portrait by the Flemish artist Jan van Eyck, using rudimentary hatching and cross-hatching to model the figure. Barton fumbled the proportions, drawing the nose twice. By contrast, a pure contour drawing of the same subject—likely Van Eyck himself—on the right side of the sheet is far more confidently executed. Despite his economy of line, Barton conveyed the sitter’s intense gaze in a sketch so fluid it seems to have made itself, beginning at the collar and trailing off the page’s right edge.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [After Jan van Eyck], 1962

Red ballpoint pen

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

After Poussin

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

After Poussin, 1962

Graphite and brush and blue ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

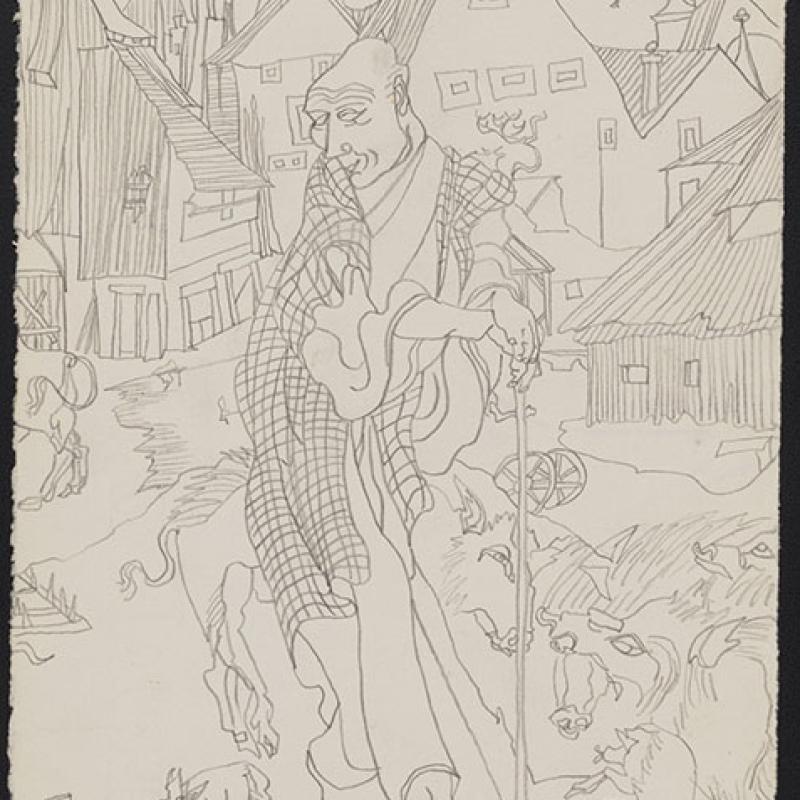

Untitled [After Dürer and Hokusai]

The robed man with a walking stick in this drawing references a nineteenth-century woodblock print by Katsushika Hokusai, in which the influential Japanese artist represented himself as an older man. The agrarian setting, however, is borrowed from an engraving by the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer. Barton’s consistent line unifies these disparate sources in a cohesive composition.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [After Dürer and Hokusai], 1962

Graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

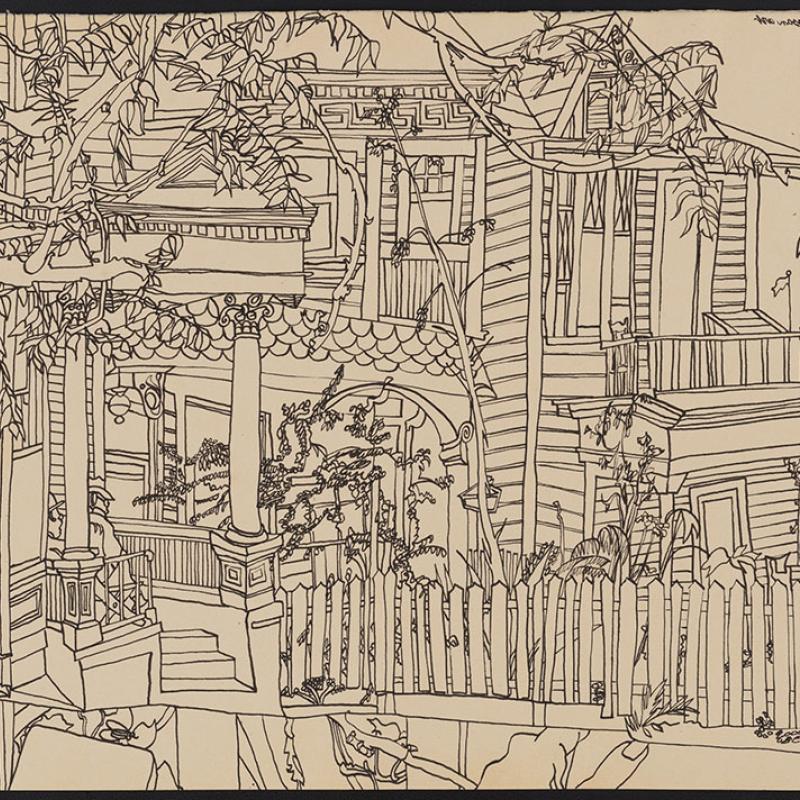

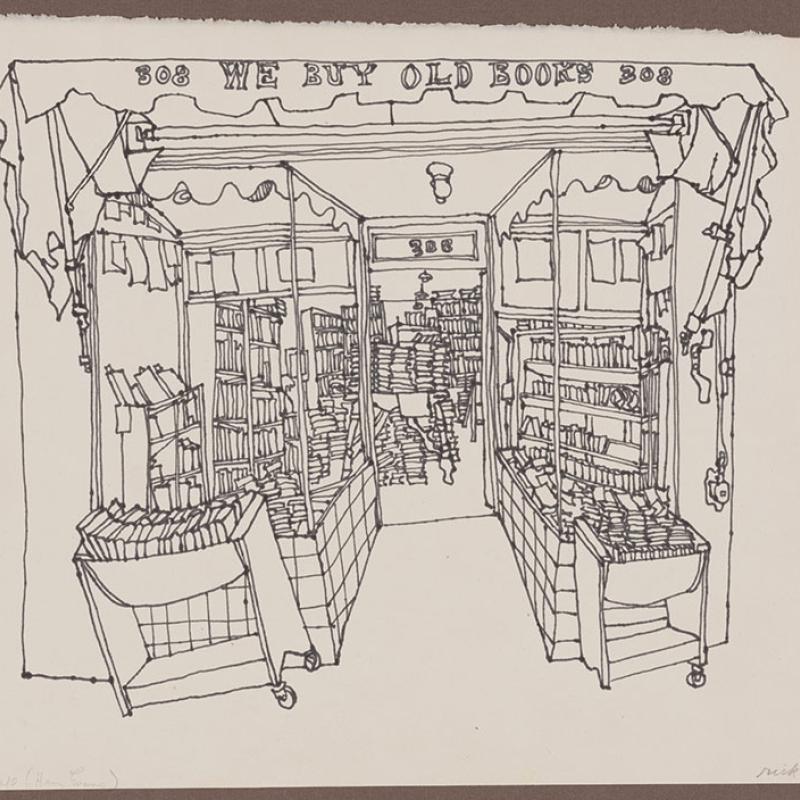

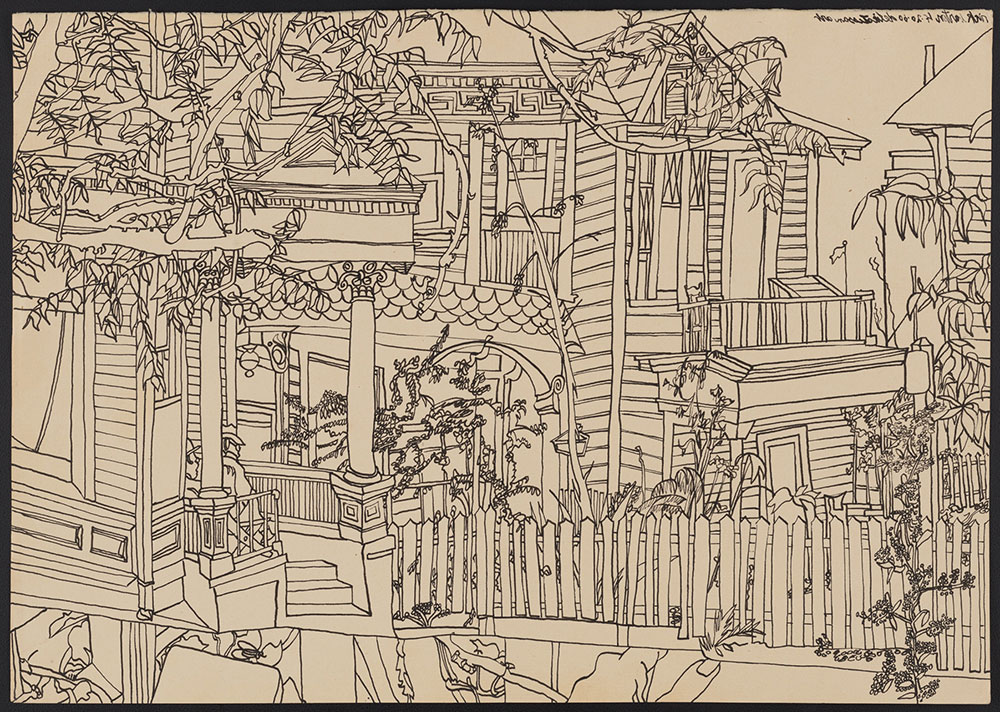

Untitled [Porpoise Bookshop, San Francisco]

Henry Evans opened the Porpoise Bookshop, shown here at its second location on Clement Street in San Francisco, in 1953. The store housed the Peregrine Press, which Evans had established four years earlier. From 1958 to 1963, he printed more than a dozen of Barton’s linocuts under the bookshop’s imprint, in editions of between 50 and 120.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Porpoise Bookshop, San Francisco], December 1958

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

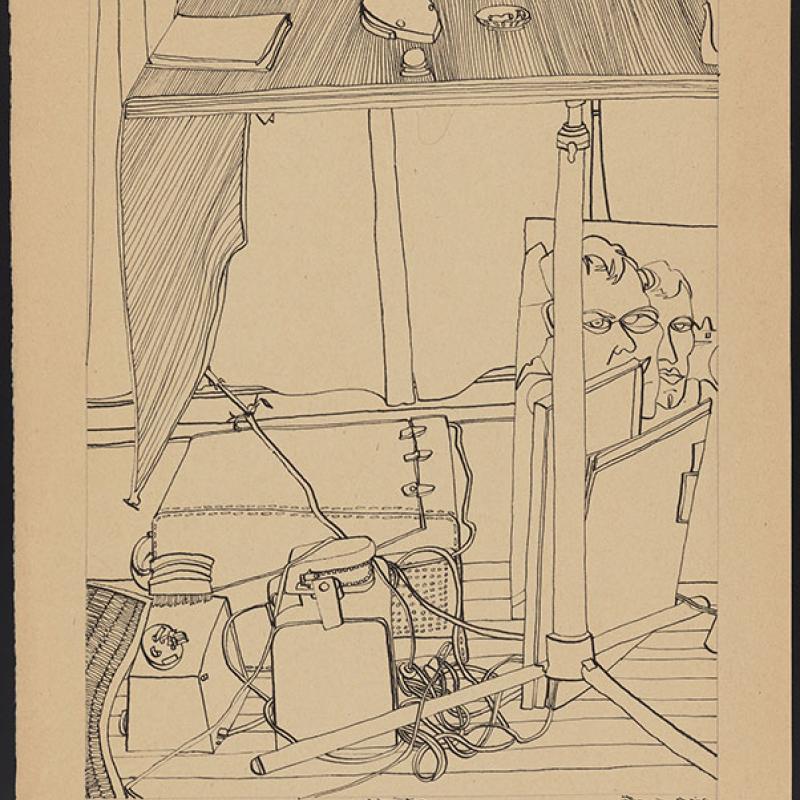

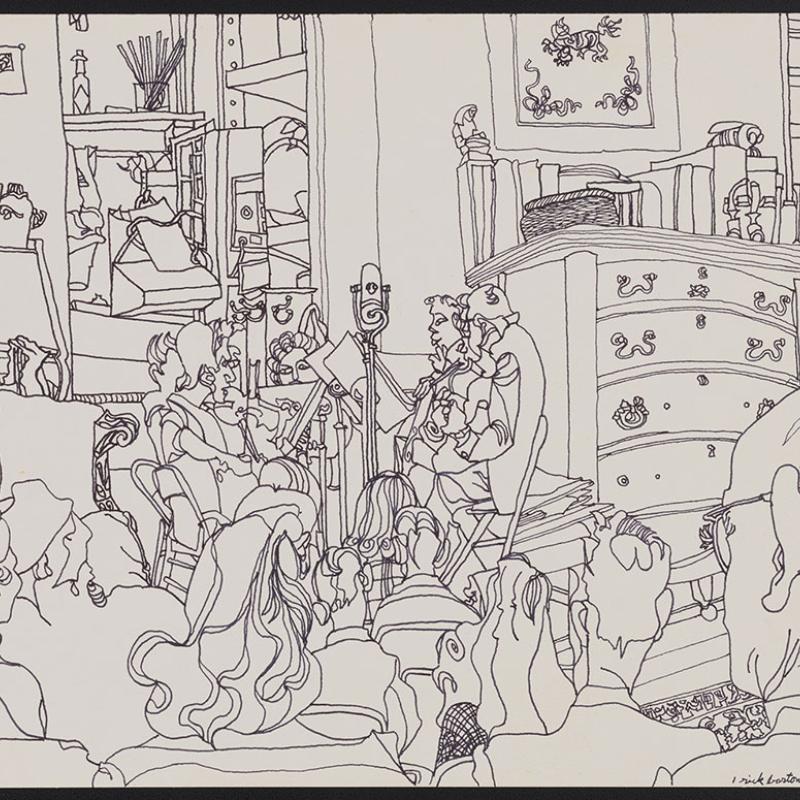

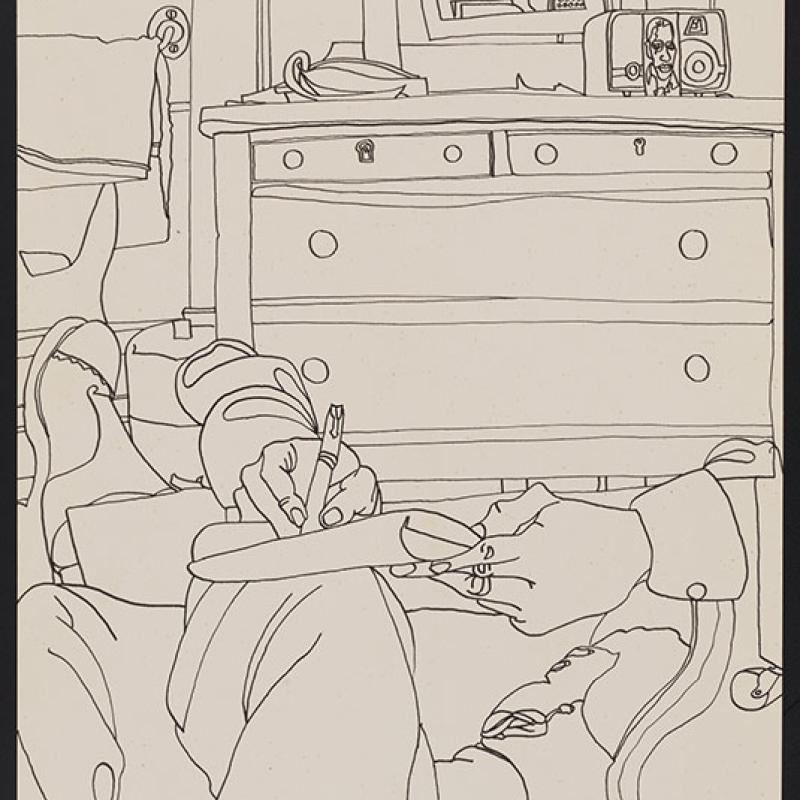

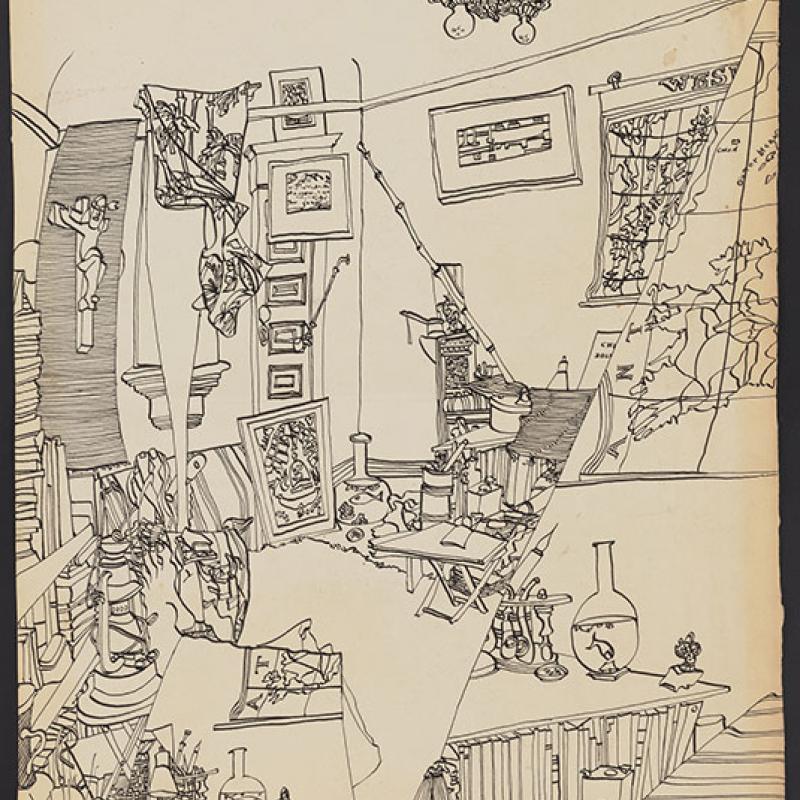

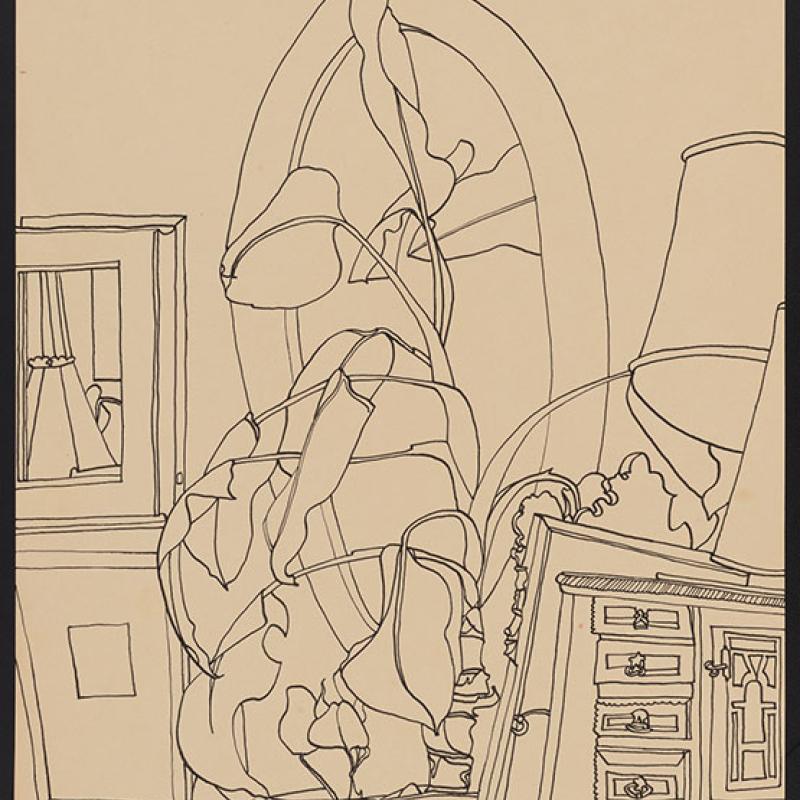

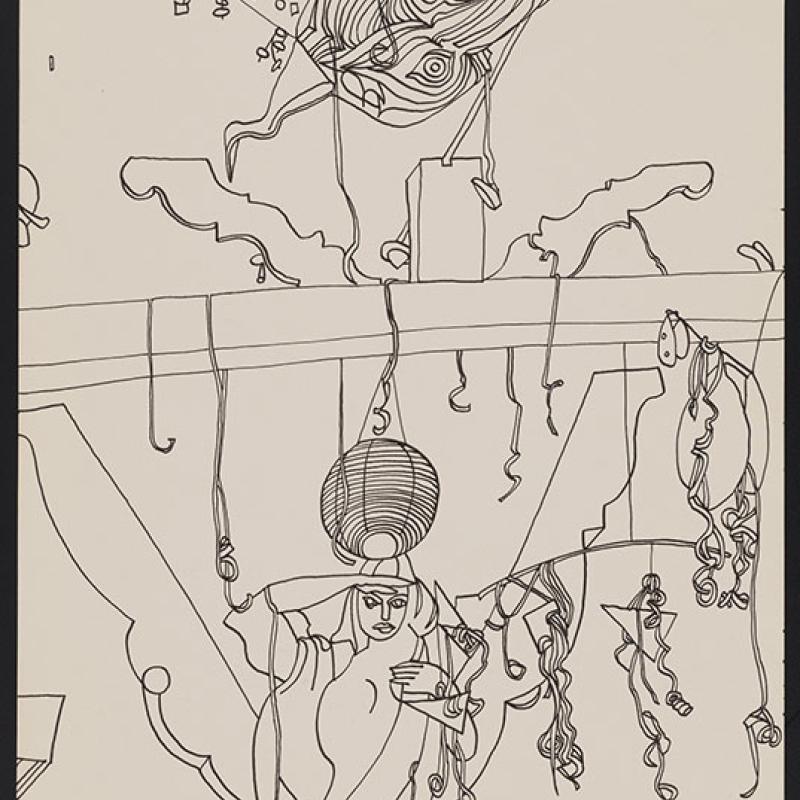

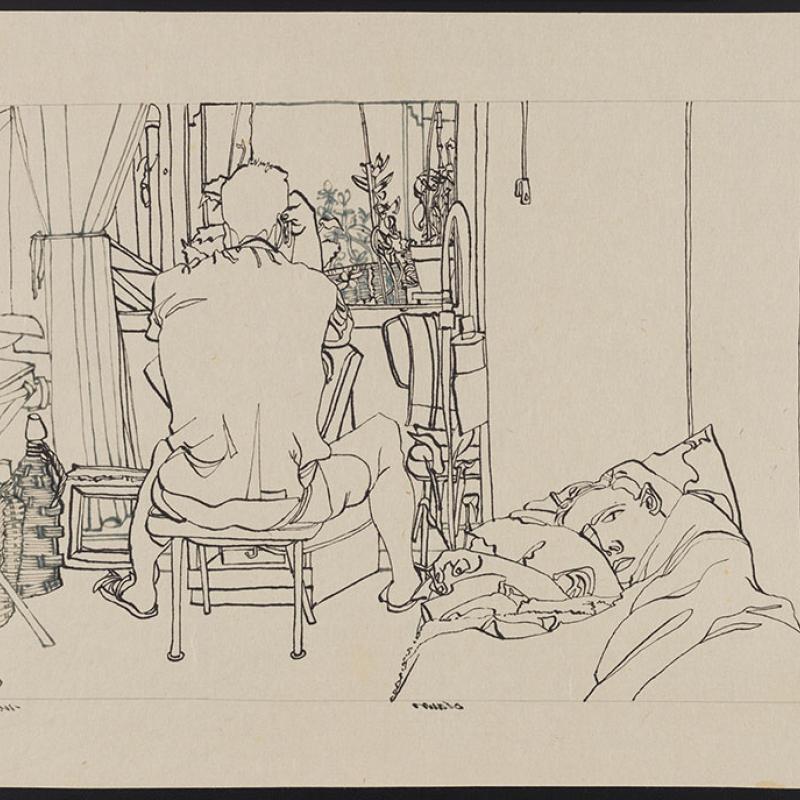

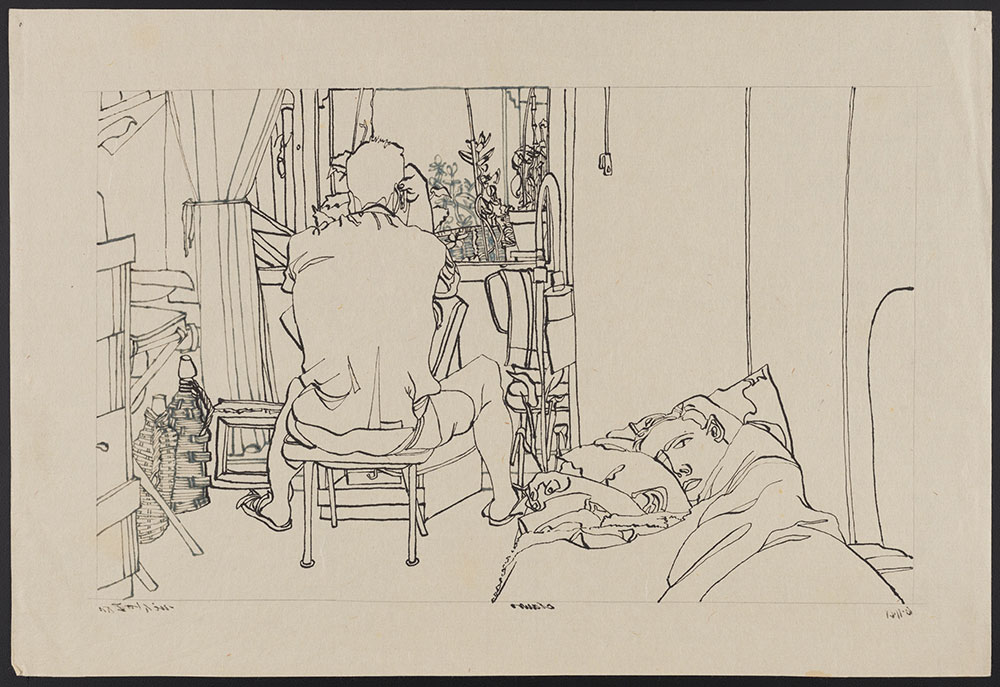

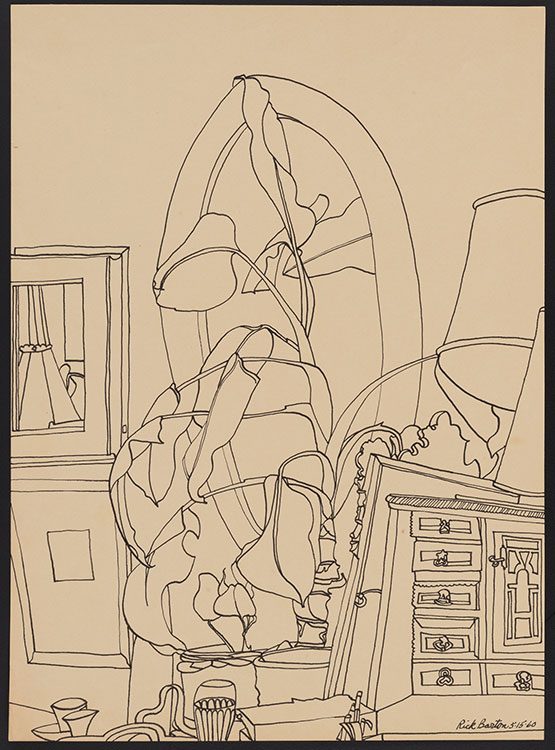

Intimate Interiors

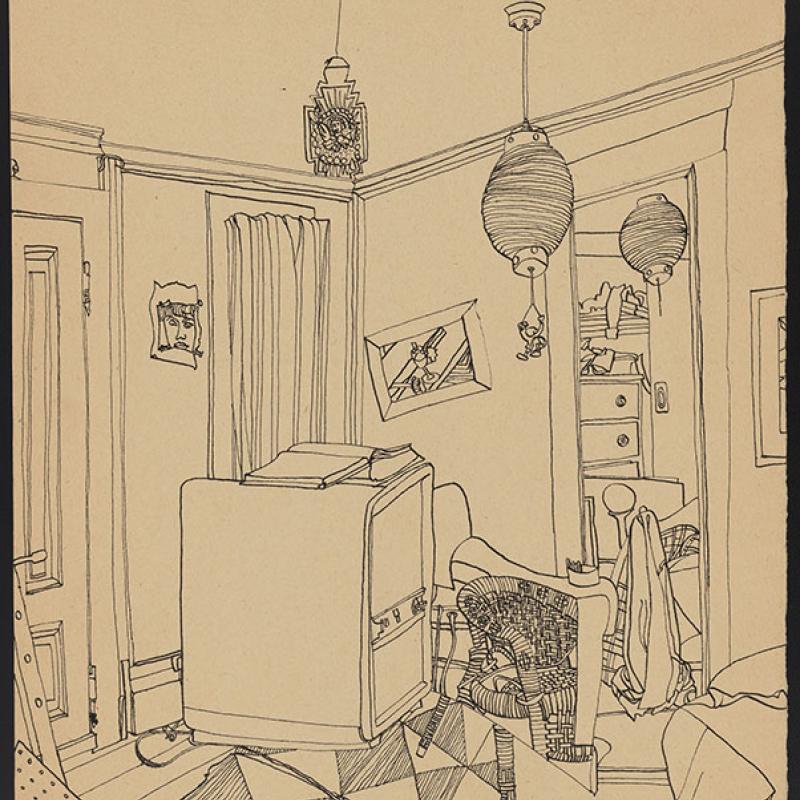

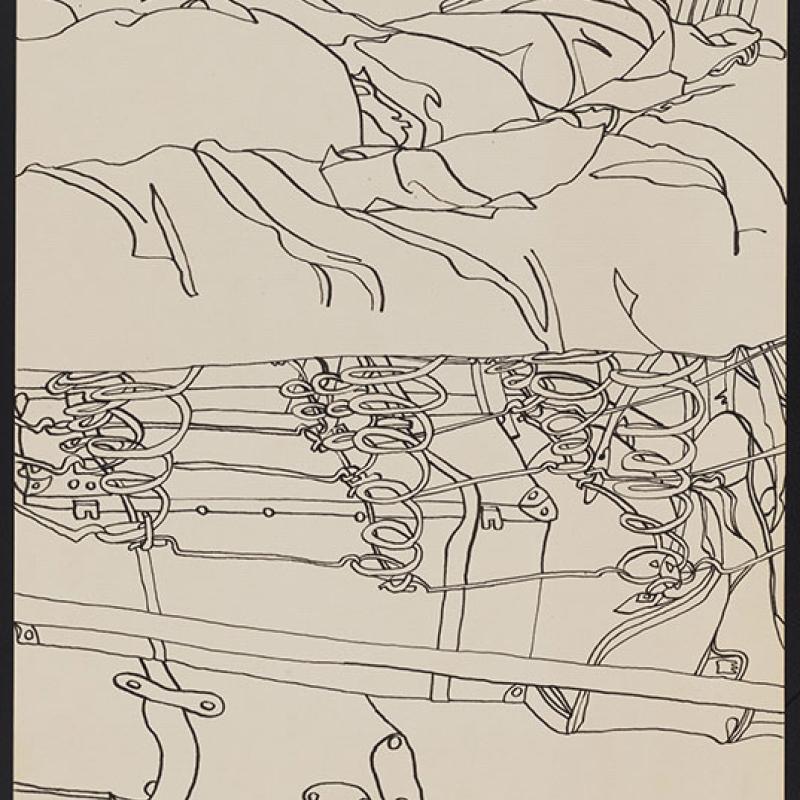

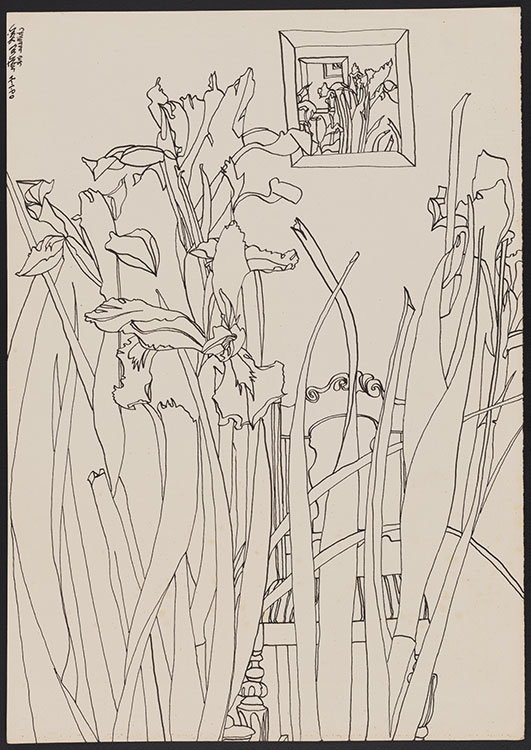

Barton led a peripatetic life, often traveling and otherwise staying in rented rooms in San Francisco and the bohemian enclave of Sausalito. No feature of these modest spaces escaped his observation. He lavished as much care on representations of light sockets and bedsprings as he did on portrayals of human figures. At times he focused on just a few details, but often he corralled crowded interiors into complex, fractured compositions. He compared himself to a spider spinning its web. Like the French artist Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Barton depicted his own earlier works within new drawings. He also frequently inserted himself engaged in the act of drawing into his compositions, underscoring the sense of an interior world consumed by art.

Untitled [Bed with reclining figure andmusicians]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Bed with reclining figure and

musicians], 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

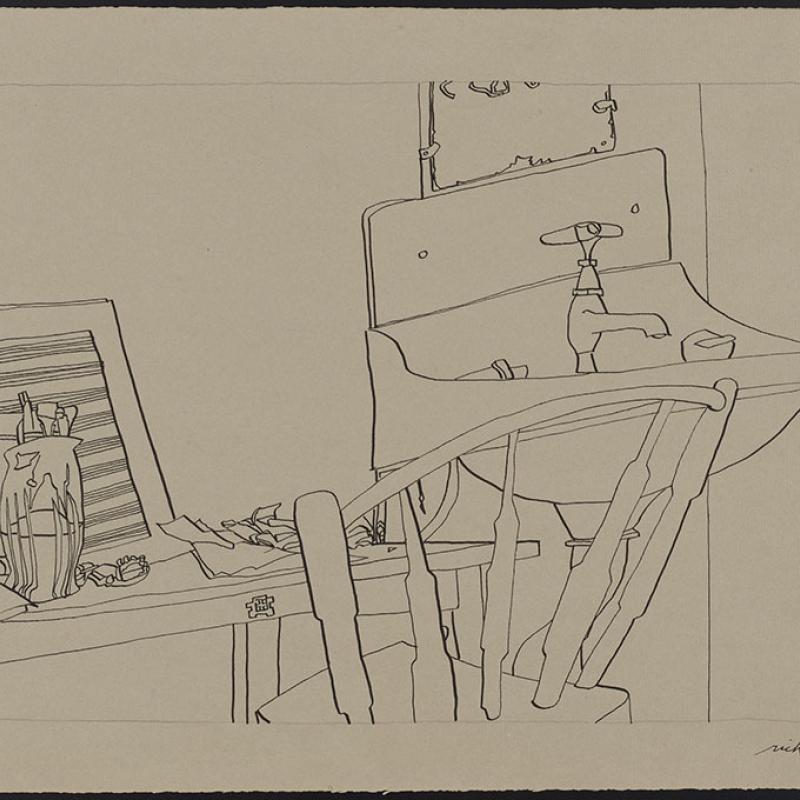

Untitled [Sink and chair]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Sinknd chair],

September 1962

Pen and ink with grap

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

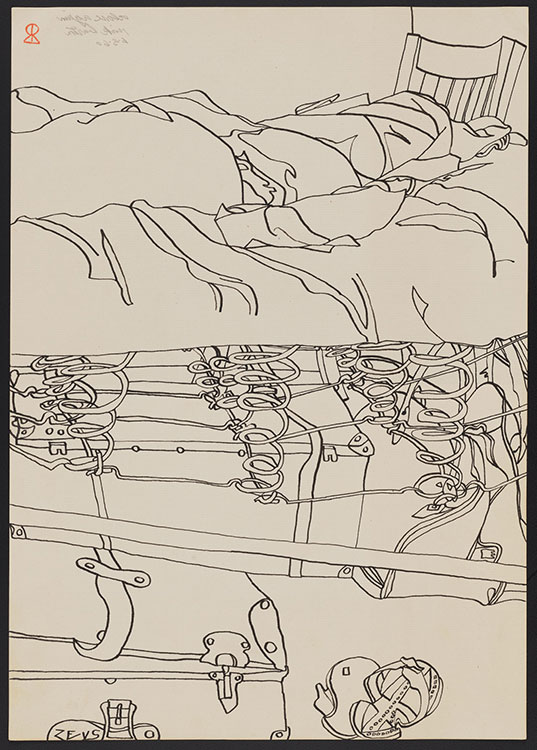

Alone Again

Here Barton dissects the layers of his bed, from the crumpled sheets on top to the intermediary bedsprings and frame, down to suitcases and sandals on the floor. Even without its heartbreaking inscription, “Alone again,” this peculiar visual inventory conveys a sense of solitude and itinerancy.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Alone Again, June 3, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Two figures]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Two figures], June 11, 1961

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

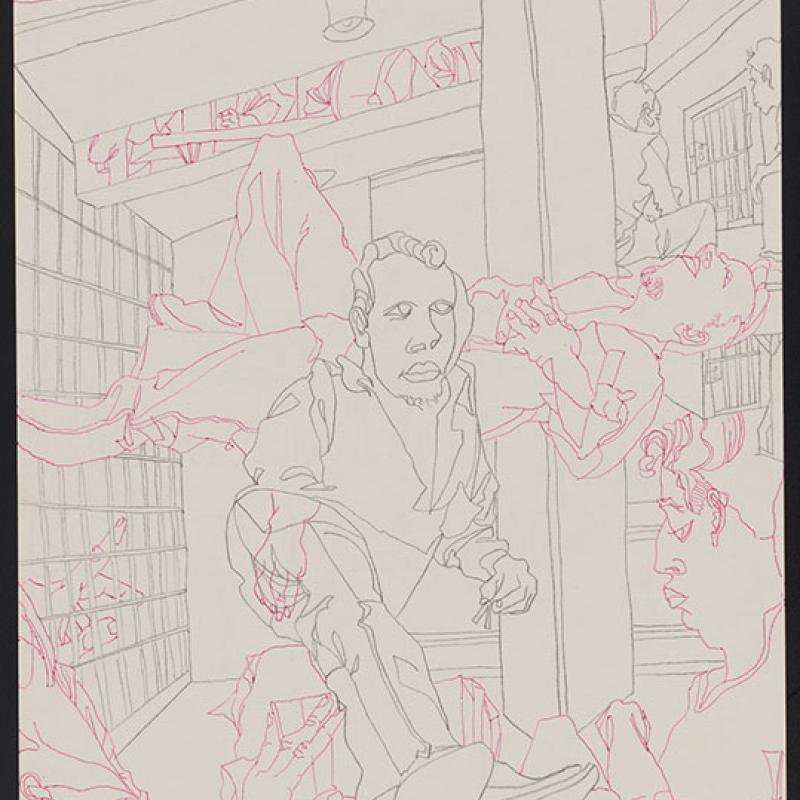

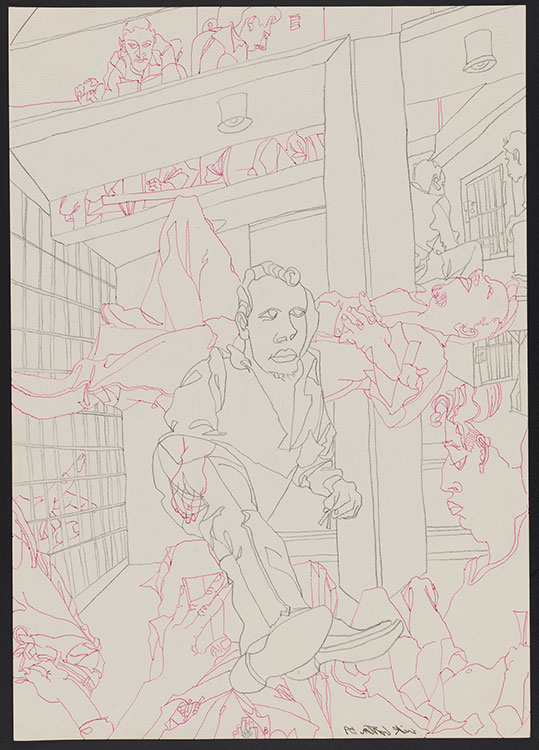

Portrait of Russ Zerbe

This sheet is filled with figures and drawings of figures, making it difficult to distinguish between the representation of subjects and the representation of the representation of subjects. Russ Zerbe, who was a lover of Barton’s, is identified as the sitter in the composition’s central portrait; Zerbe may be shown elsewhere in the room as well. Compositions such as these suggest that drawing was the primary lens through which Barton experienced the world.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Portrait of Russ Zerbe, 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Interior with fishbowls and map]

Barton kept aquariums in his childhood bedroom. The image of the adolescent artist in his room surrounded by fishbowls presages a larger current in Barton’s art: his tendency to reflect, refract, and displace his surroundings, as if they were being viewed through a glass or another vessel filled with water.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Interior with fishbowls and map], February 5, 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

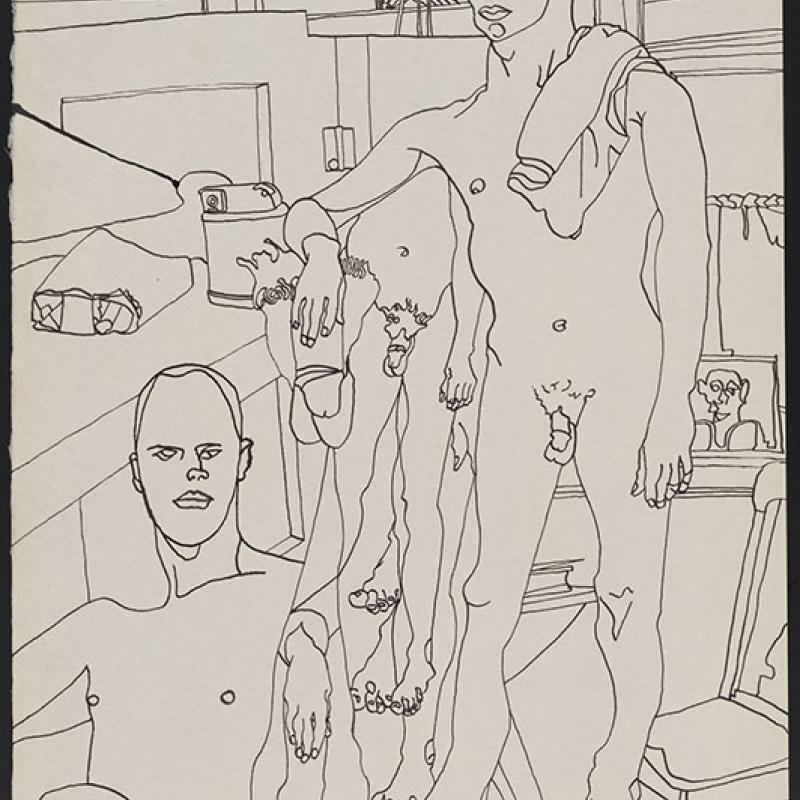

Untitled [Nudes]

This drawing points to an affinity with the early work of Andy Warhol. Barton addressed some of the same subjects that Warhol did—notably, beautiful youths and flowers—in a similarly delicate linear style. It is conceivable that Barton was familiar with Warhol’s early drawings, which were exhibited in New York and circulated— though not widely—through self-published books in the early 1950s, before Barton moved to the Bay Area.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Nudes], October 5, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

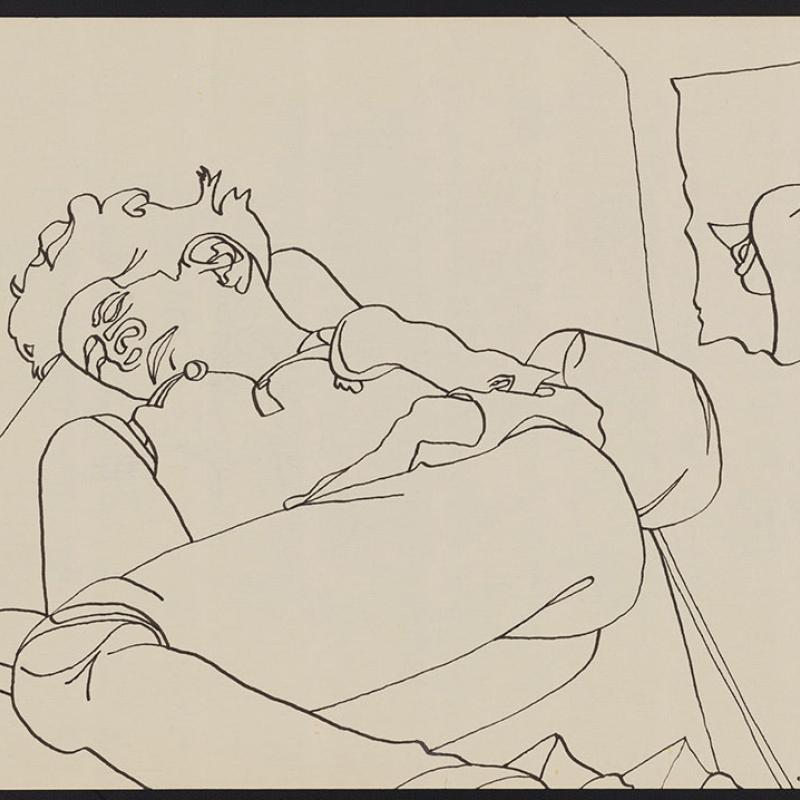

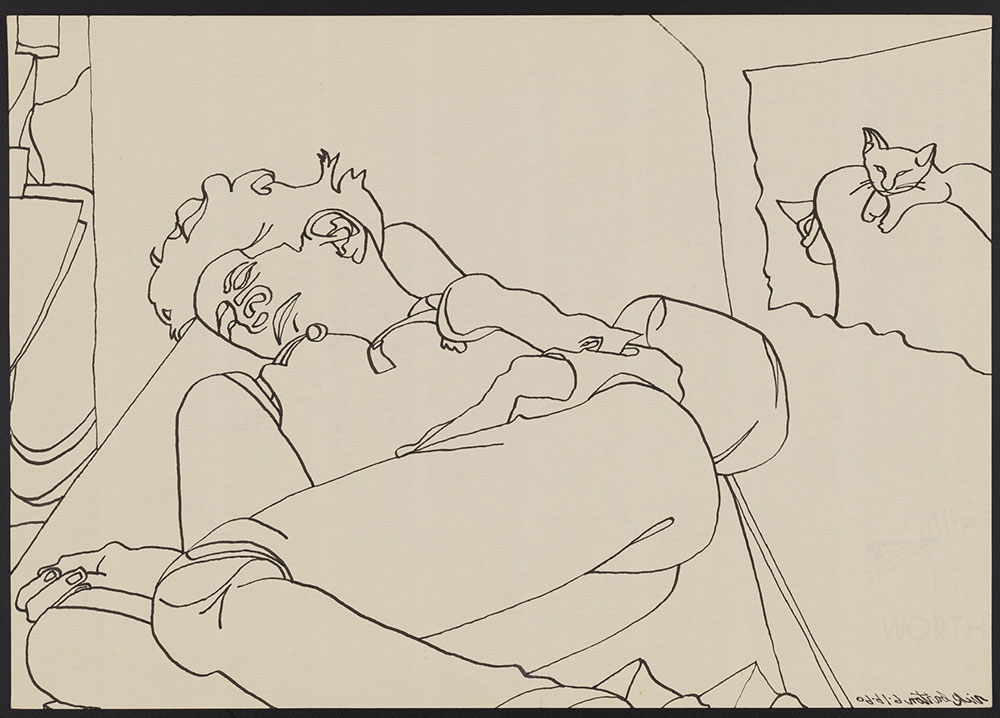

Untitled [Sleeping man]

Along with several others, this work suggests that Barton was familiar with the drawings of Jean Cocteau. The French avant-gardist’s unflinching depictions of gay subjects, including bars that he frequented, would certainly have been of interest to the young American artist, as they were to his contemporary Andy Warhol. This tender drawing of a sleeping man resembles a series of drawings that Cocteau published of his lover Raymond Radiguet, a writer, in the 1920s. (Barton’s drawing of leaves on the sheet’s reverse is visible.)

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Sleeping man], 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Again the Angel of the Celestial Bells

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Again the Angel of the Celestial Bells,

August 15, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

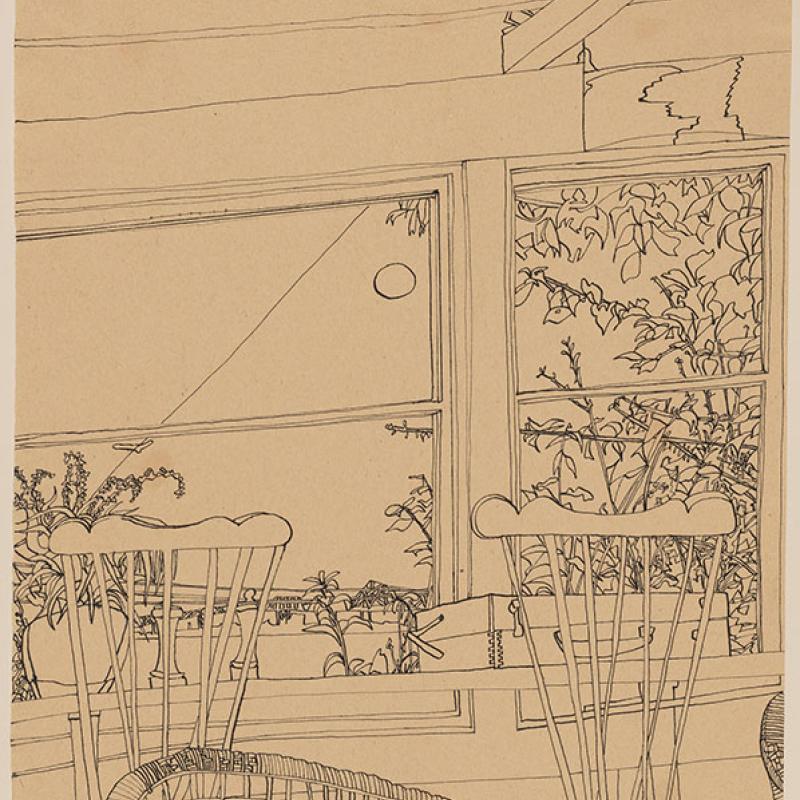

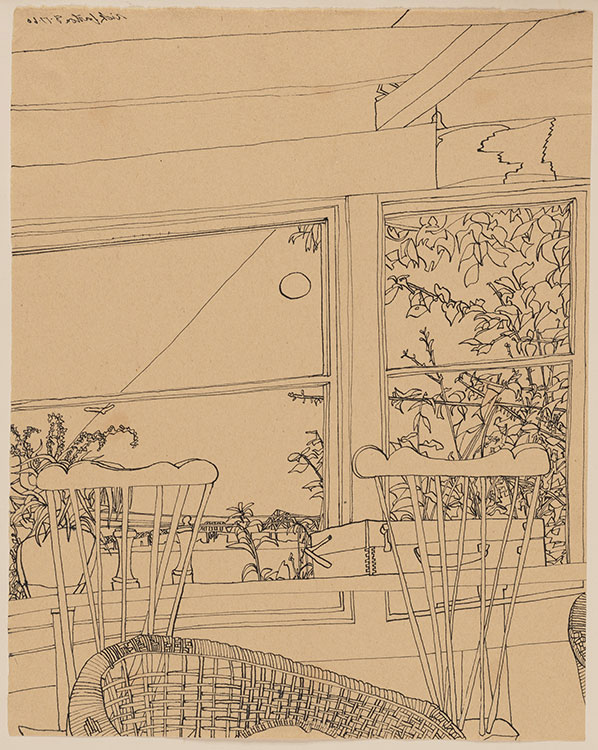

Untitled [Window]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Window], August 17, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Studio I

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Studio I, June 11, 1961

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Banners and Manners

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Banners and Manners, April 27, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Disembodied head]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Disembodied head], April 8, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Bedroom concert]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Bedroom concert], 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

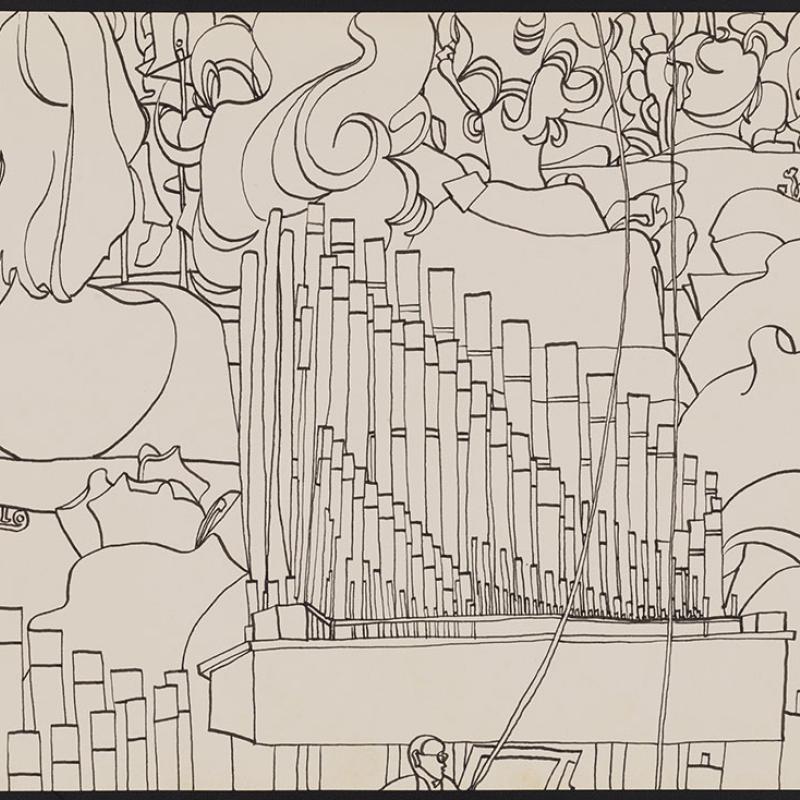

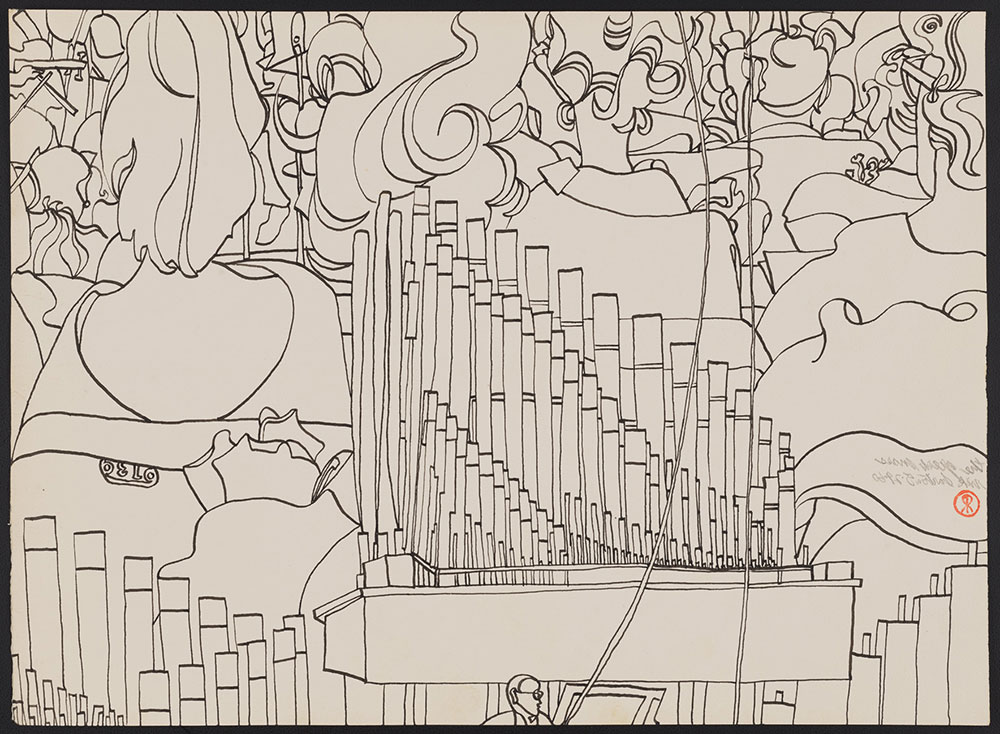

Rick Barton's Chinese Line

Barton adored classical music, which he often listened to while he drew. In this drawing, the domestic setting is signaled by a bookshelf, a section of paneled wall, and an unadorned lightbulb hanging from a chain. At left, violinists and a cellist surround a piano; an audience hovers around them. The line forming the headless piano player’s left arm extends from the milk poured by a rendering of the Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer’s Milkmaid (ca. 1660). In Barton’s world, line was capable of stitching together past and present, painting and music, and perhaps most importantly, art and life.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rick Barton’s Chinese Line, April 25, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

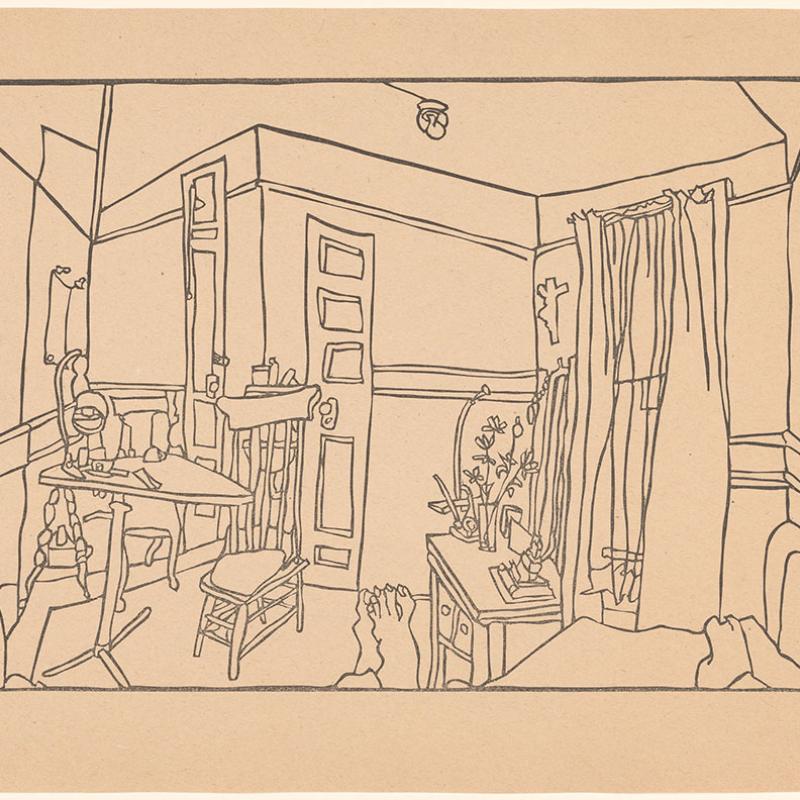

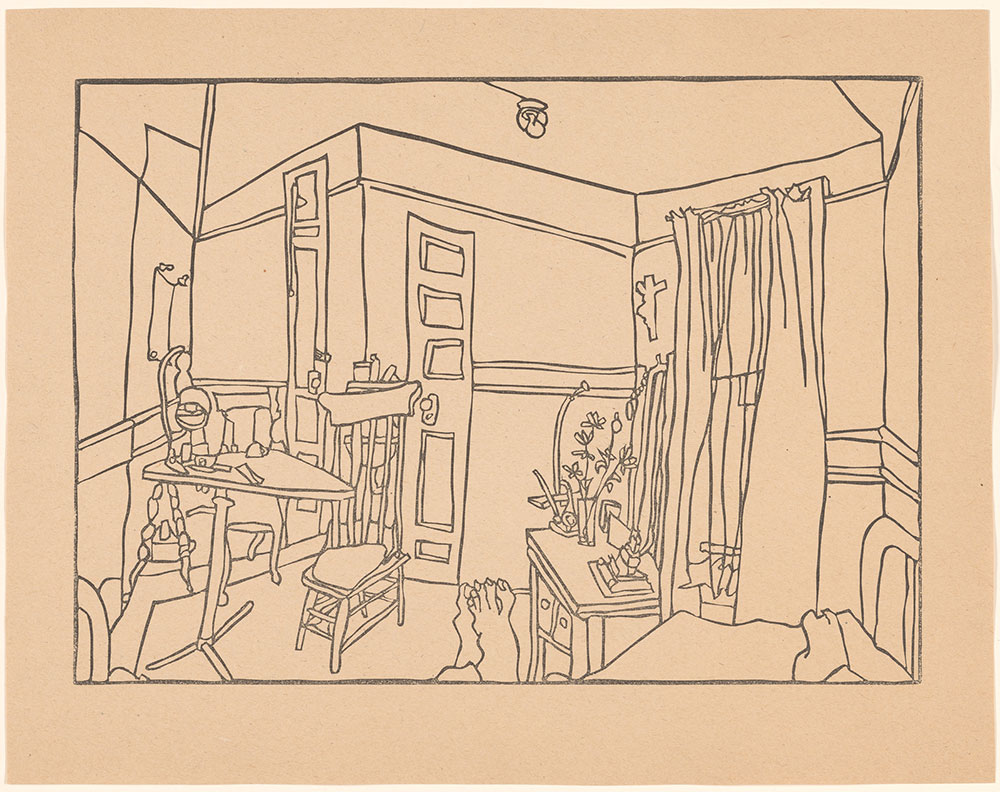

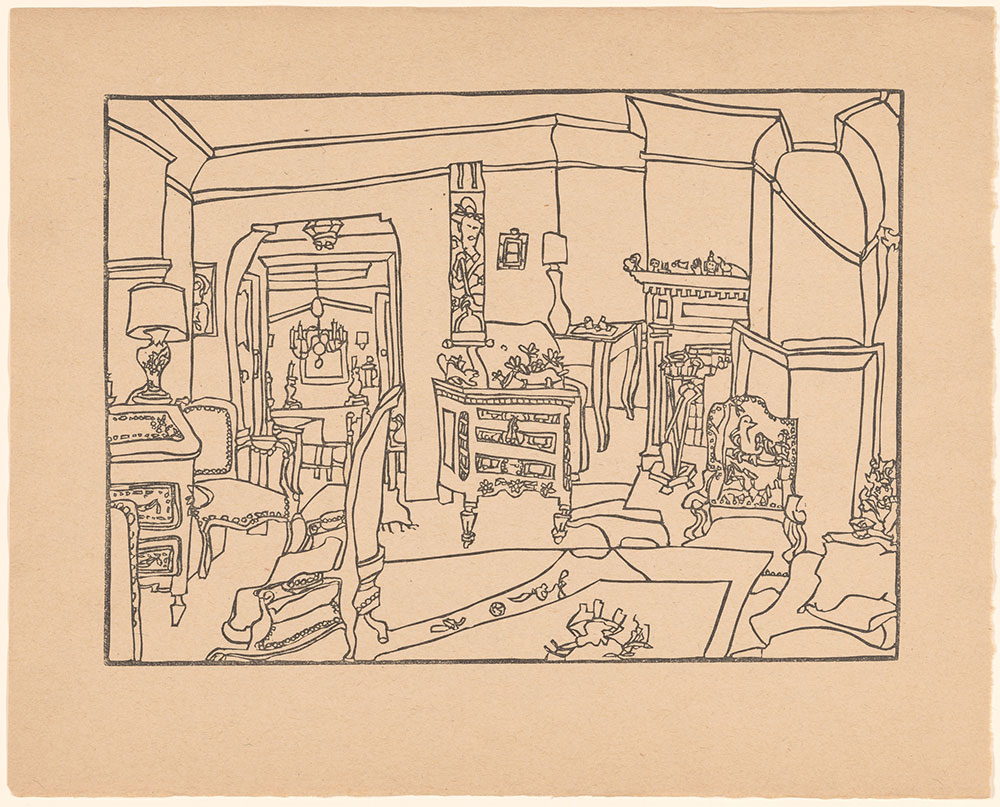

Rooms, plate 2

Barton had worked as a printer’s apprentice as a boy, but it was not until he met Henry Evans that the artist began to produce his own prints. Using linoleum blocks that Evans provided, Barton cut prints in a linear style similar to that of his drawings. The plates in this portfolio, printed by hand at Evans’s Peregrine Press, portray a range of rooms, from the spare interior at left, in which Barton’s feet are visible, to the more sumptuously decorated space at right.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rooms, plate 2

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1958, published 1960

10 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 60

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.277

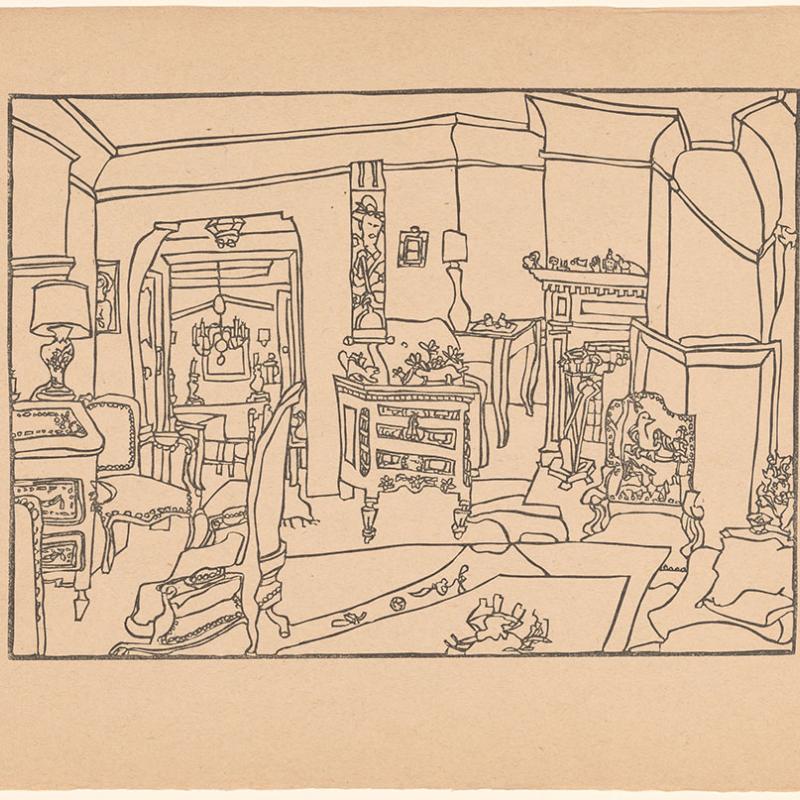

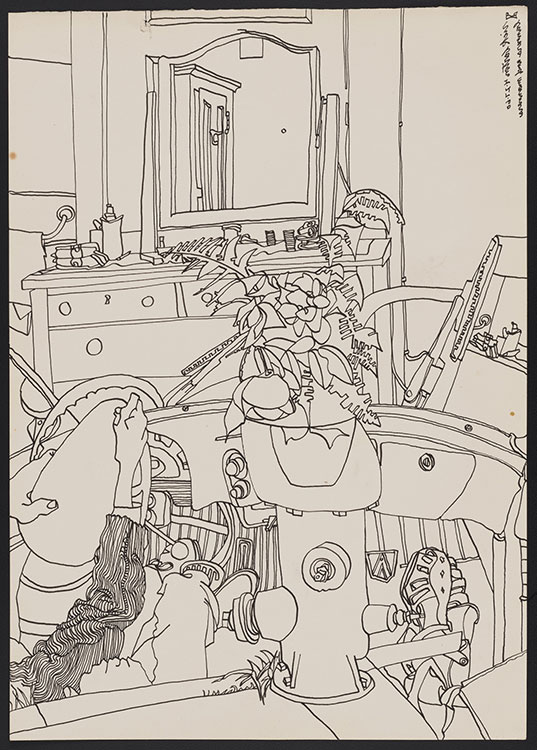

Rooms, plate 4

Barton had worked as a printer’s apprentice as a boy, but it was not until he met Henry Evans that the artist began to produce his own prints. Using linoleum blocks that Evans provided, Barton cut prints in a linear style similar to that of his drawings. The plates in this portfolio, printed by hand at Evans’s Peregrine Press, portray a range of rooms, from the spare interior at left, in which Barton’s feet are visible, to the more sumptuously decorated space at right.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rooms, plate 4

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1958, published 1960

10 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 60

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.277

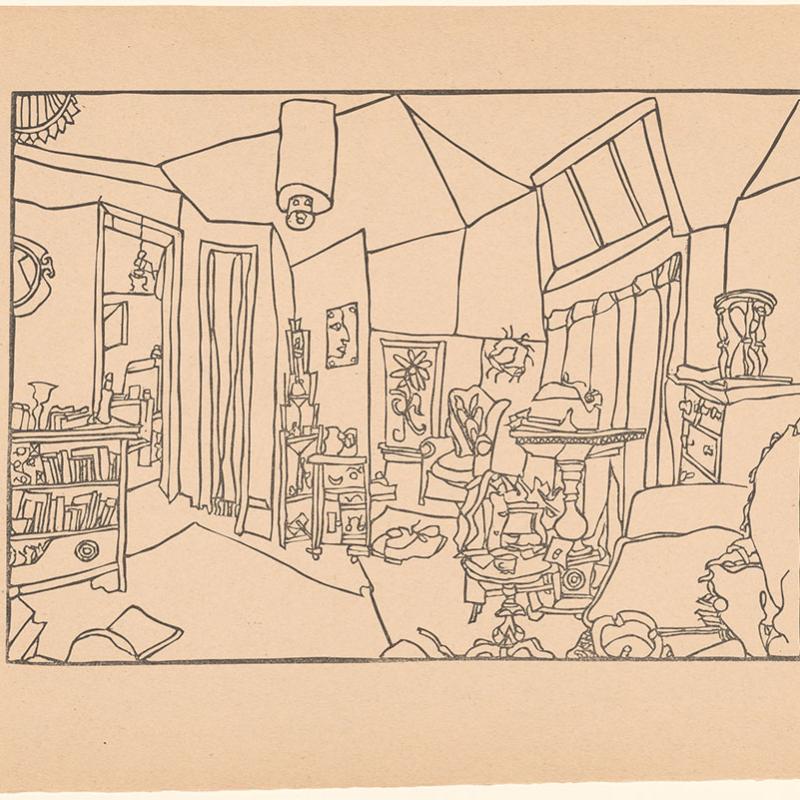

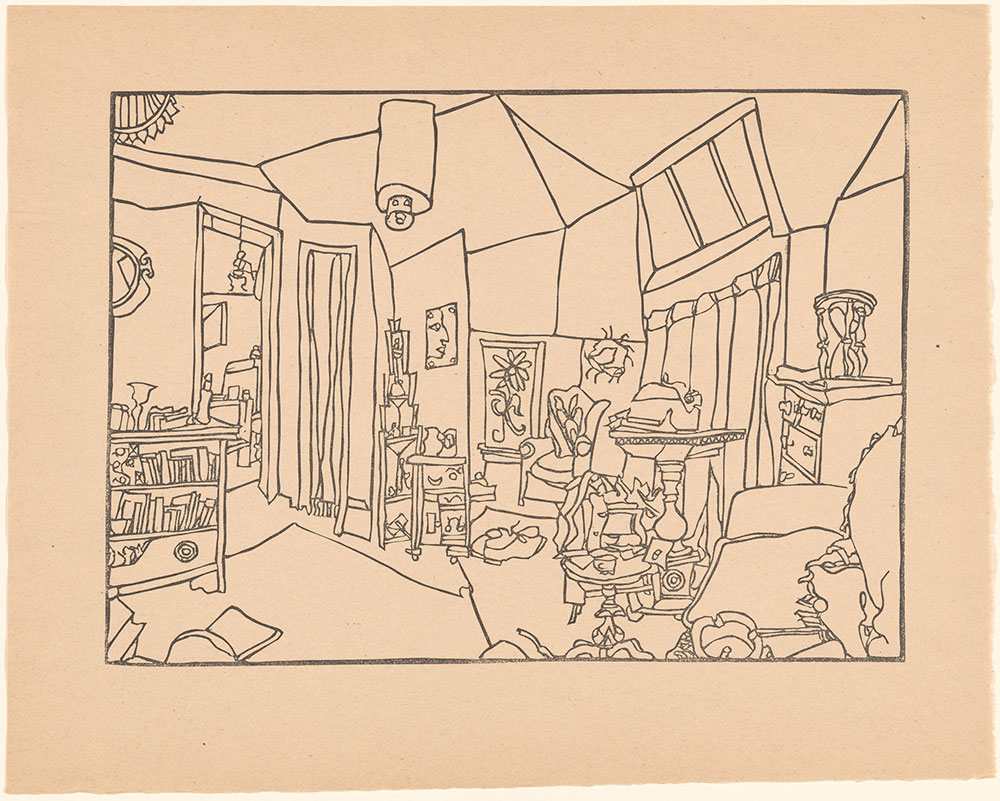

Rooms, plate 7

Barton had worked as a printer’s apprentice as a boy, but it was not until he met Henry Evans that the artist began to produce his own prints. Using linoleum blocks that Evans provided, Barton cut prints in a linear style similar to that of his drawings. The plates in this portfolio, printed by hand at Evans’s Peregrine Press, portray a range of rooms, from the spare interior at left, in which Barton’s feet are visible, to the more sumptuously decorated space at right.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Rooms, plate 7

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1958, published 1960

10 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 60

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.277

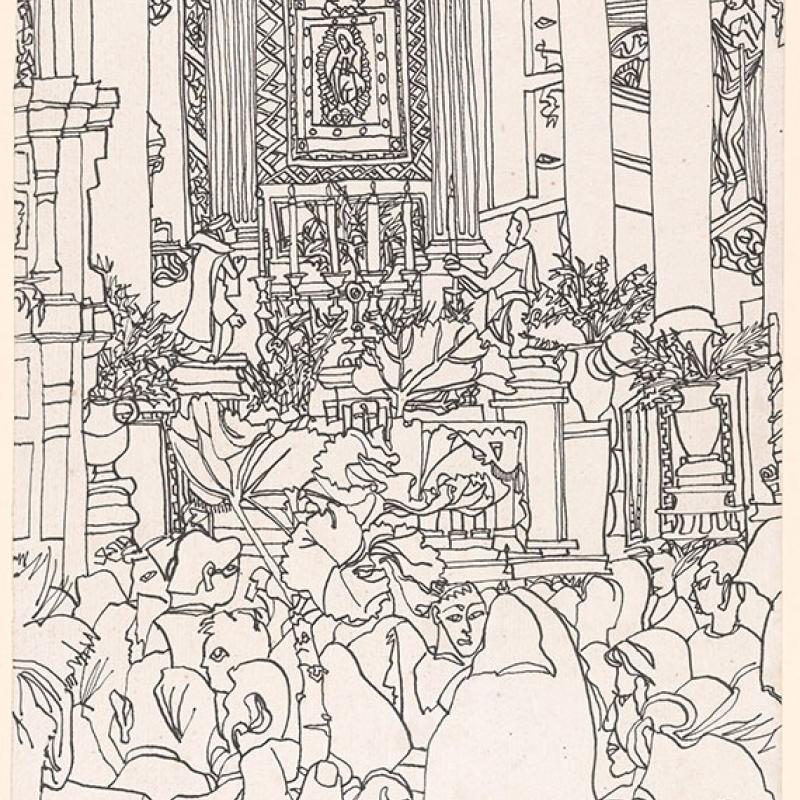

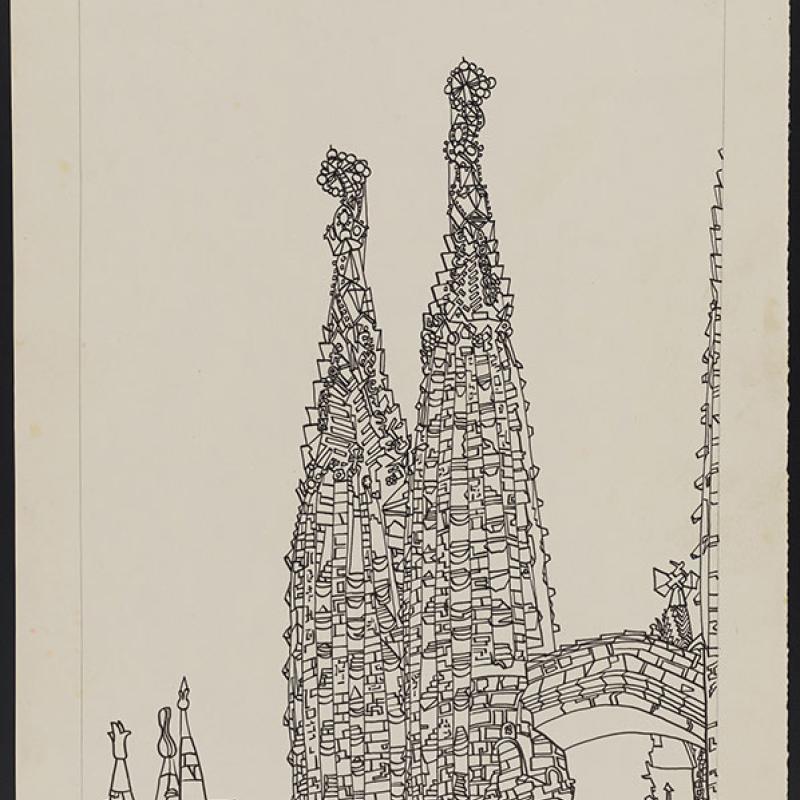

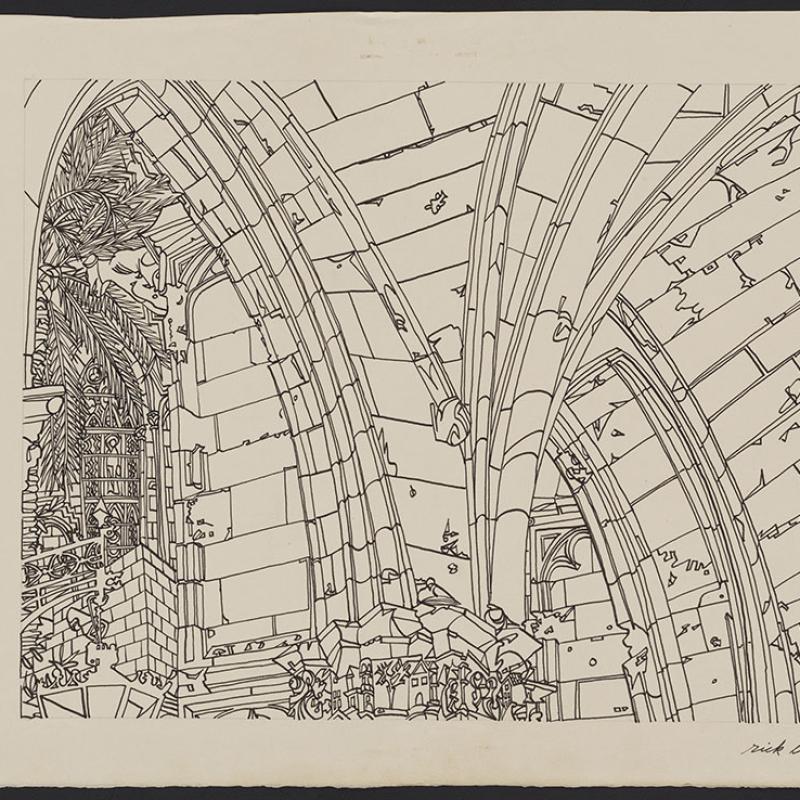

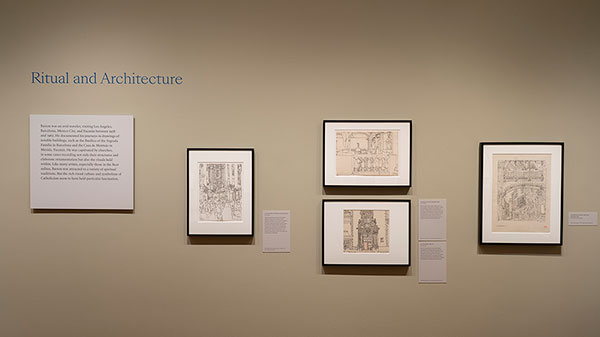

Ritual and Architecture

Barton was an avid traveler, visiting Los Angeles, Barcelona, Mexico City, and Yucatán between 1958 and 1962. He documented his journeys in drawings of notable buildings, such as the Basílica of the Sagrada Família in Barcelona and the Casa de Montejo in Mérida, Yucatán. He was captivated by churches, in some cases recording not only their structures and elaborate ornamentation but also the rituals held within. Like many artists, especially those in the Beat milieu, Barton was attracted to a variety of spiritual traditions. But the rich visual culture and symbolism of Catholicism seem to have held particular fascination.

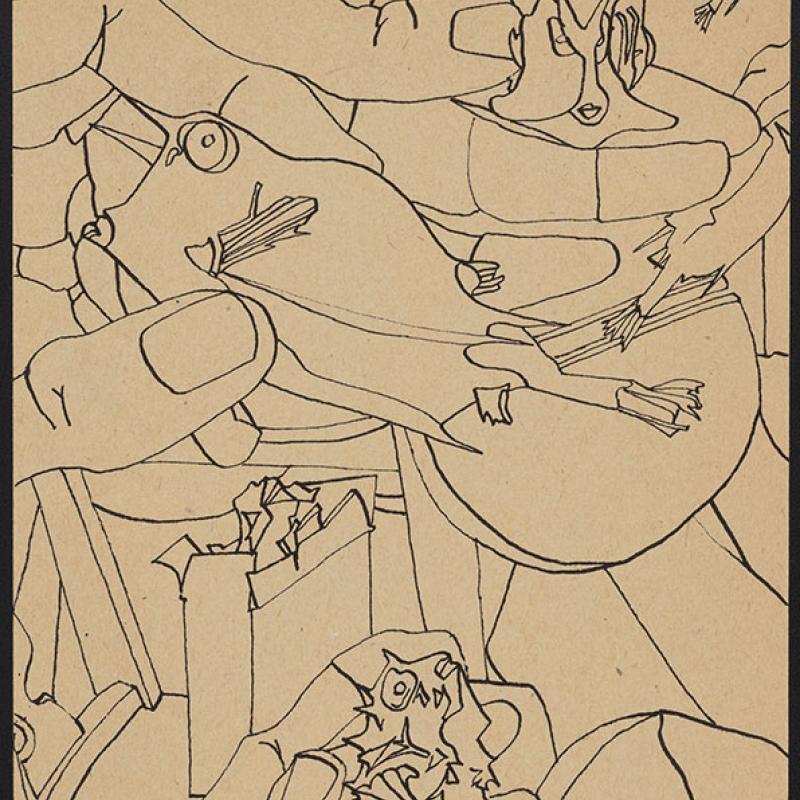

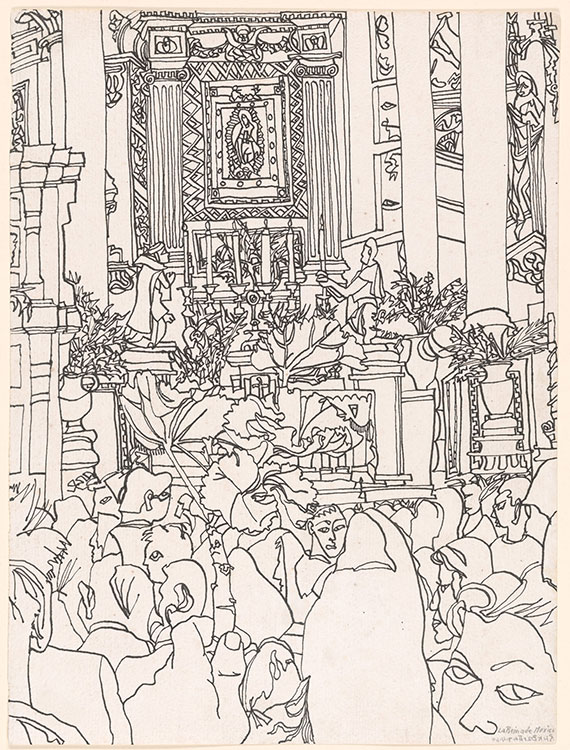

La reina de Mexico (The Queen of Mexico)

This drawing shows a throng of the faithful gathered in the nave of a church, almost certainly the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. The consistency of Barton’s line tends to flatten his images, but close observation reveals a thumb in the composition’s foreground, in the manner of a photographer who has accidentally obscured the lens. Just beyond and to the left, a hand holds a stem, perhaps referencing the roses in the origin story of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

La reina de Mexico (The Queen of Mexico), 1960

Pen and ink

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and

Norma Anthony; 2017.278

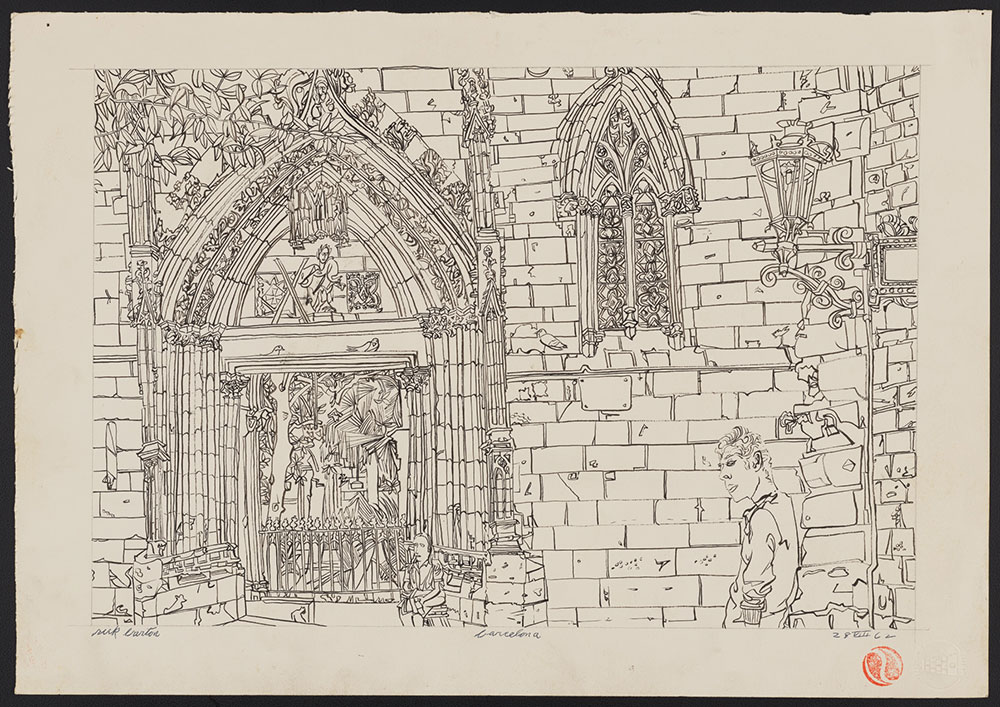

Barcelona, August 28, 1962

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Barcelona, August 28, 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

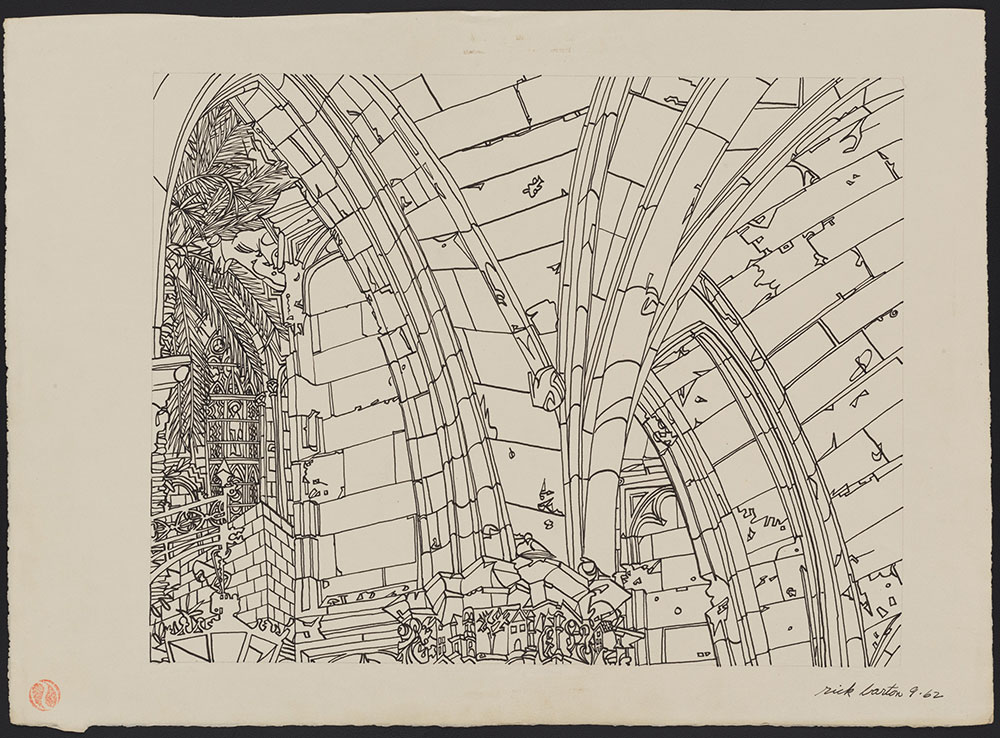

Untitled [Basílica of the Sagrada Família, Barcelona]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Basílica of the Sagrada Família, Barcelona], September 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Façade of Barcelona Cathedral]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Façade of Barcelona Cathedral], September 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

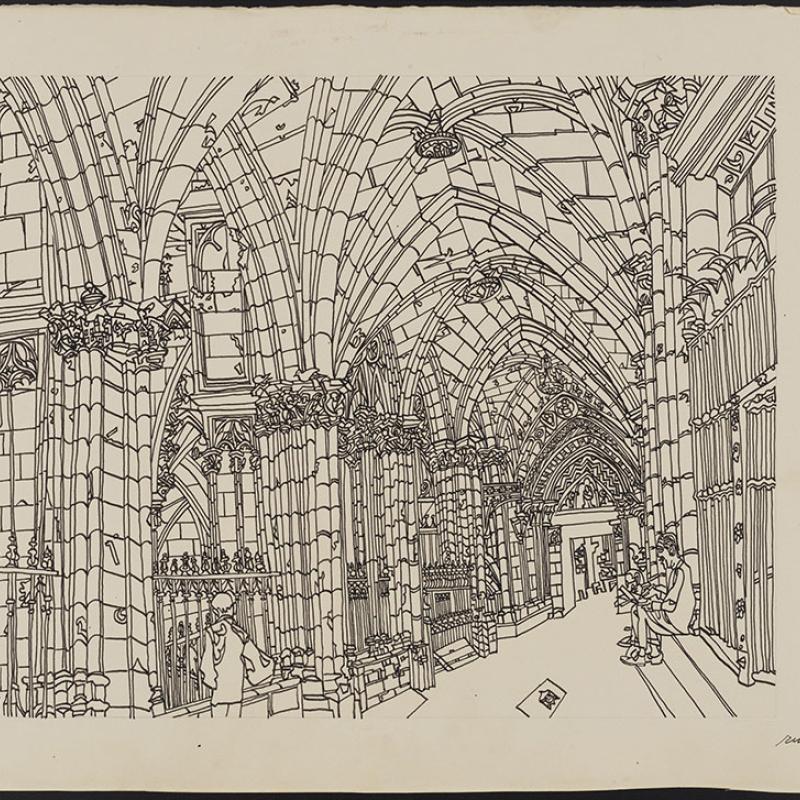

Untitled [Cloister in Barcelona Cathedral]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Cloister in Barcelona Cathedral], September 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Interior of Barcelona Cathedral withseated man]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Interior of Barcelona Cathedral with

seated man], September 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

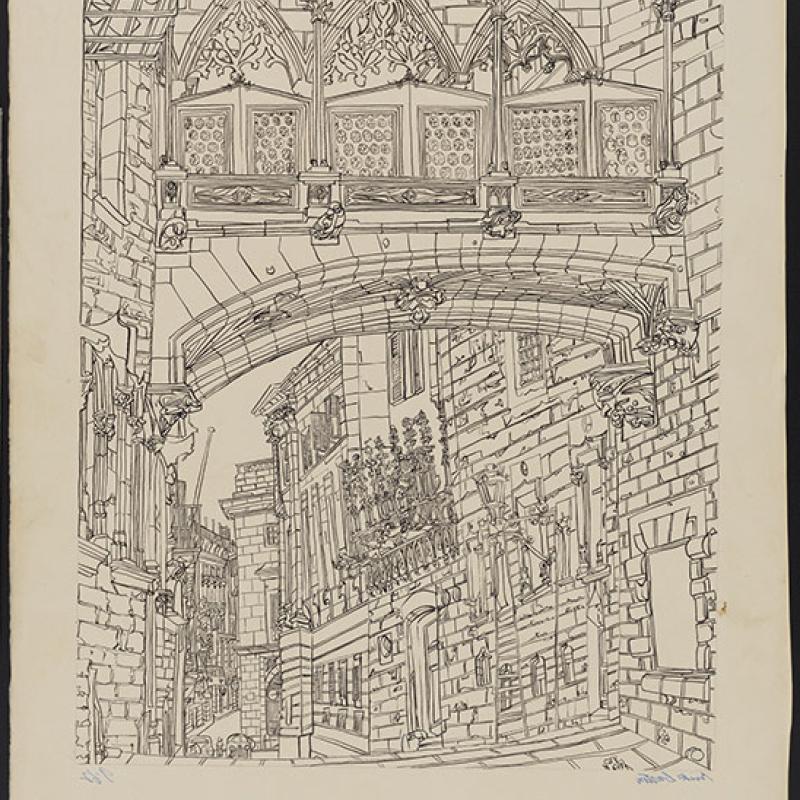

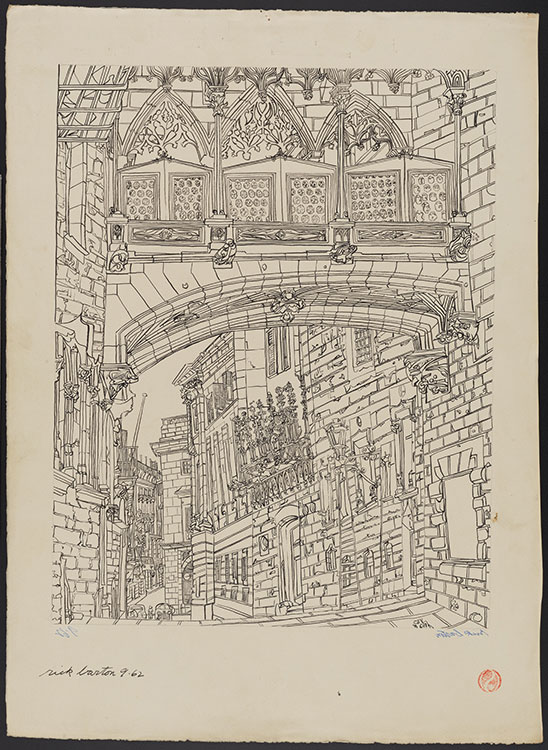

Untitled [Pont del Bisbe, Barcelona]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Pont del Bisbe, Barcelona],

September 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

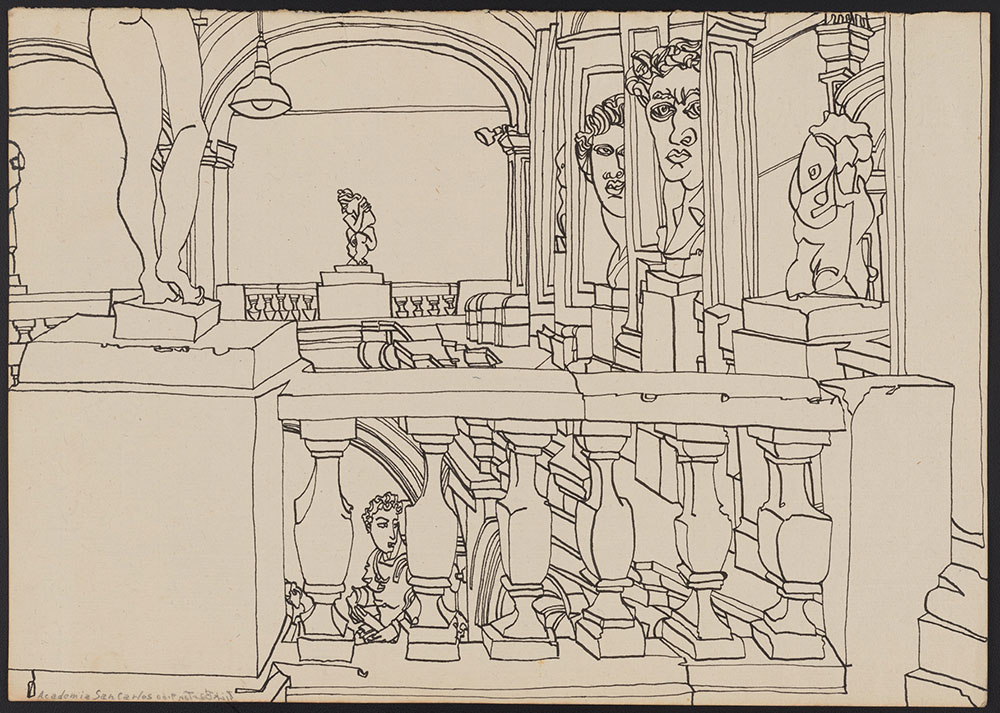

Academia San Carlos

Barton made this drawing in Mexico City, at the Academy of San Carlos. Founded in 1785 by Carlos III, king of Spain, it was the first art academy of its kind in the Americas. Since 1791 the academy has inhabited a sixteenth-century building that was previously a hospital. In this drawing of the interior, Barton focused his attention on the Neoclassical plaster casts of ancient sculptures that line the balcony.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Academia San Carlos, September 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Casa de Montejo

Barton incorporated an unusually lengthy inscription into this drawing, writing in red ink: “the doorway to the most beautiful house from new york west to china and south to merida, yucatán, mexico, the casa de montejo.” The Casa de Montejo is a sixteenth-century building located on the central square in Mérida, the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Casa de Montejo, 1960–61

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

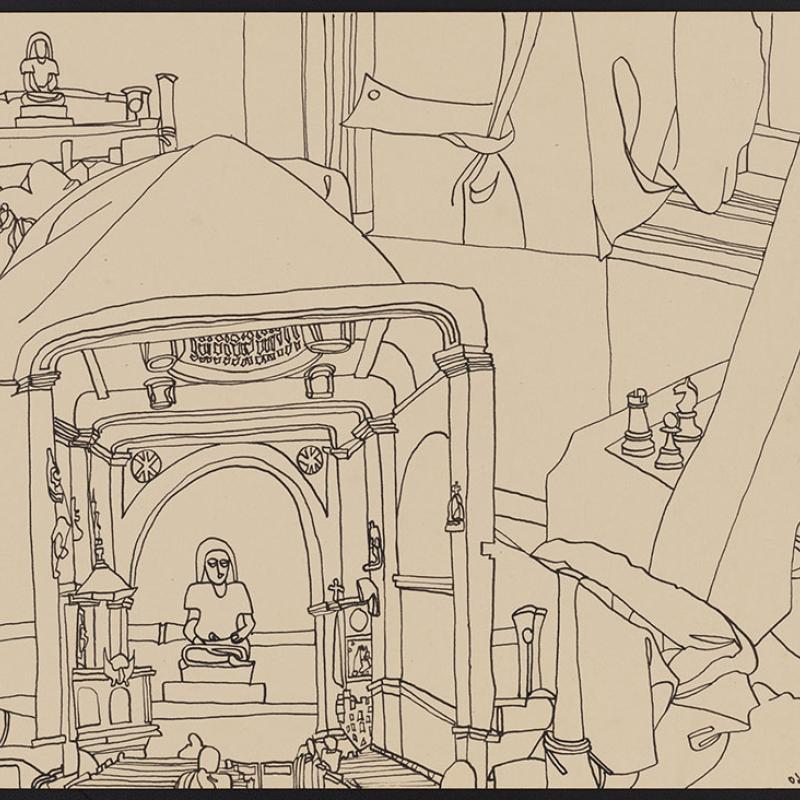

God Foil [?]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

God Foil [?], April 23, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Delicatessen Art

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Delicatessen Art, April 20, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

The Great Mass

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

The Great Mass, May 29, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

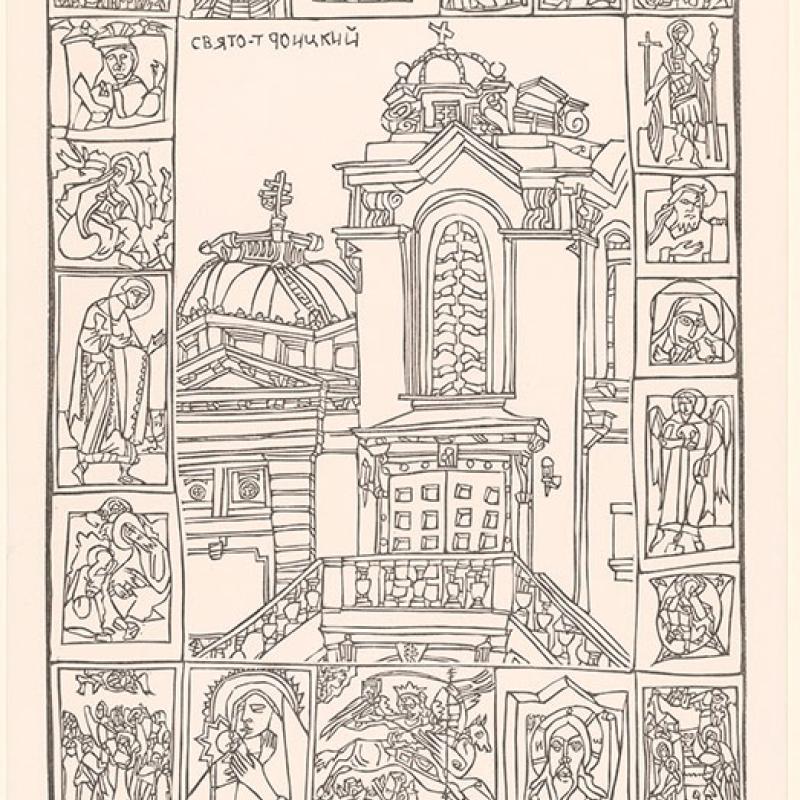

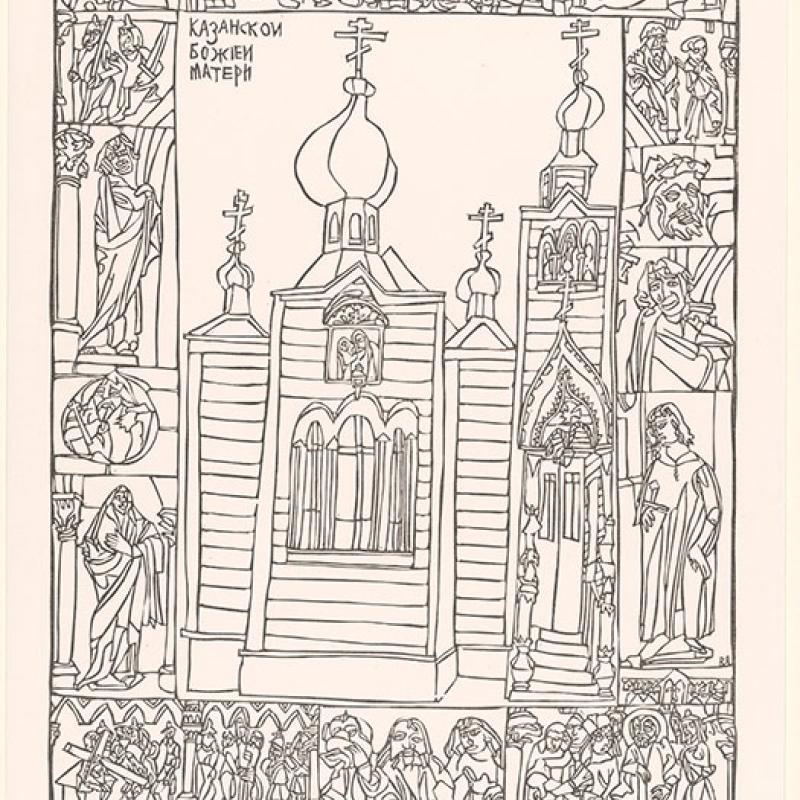

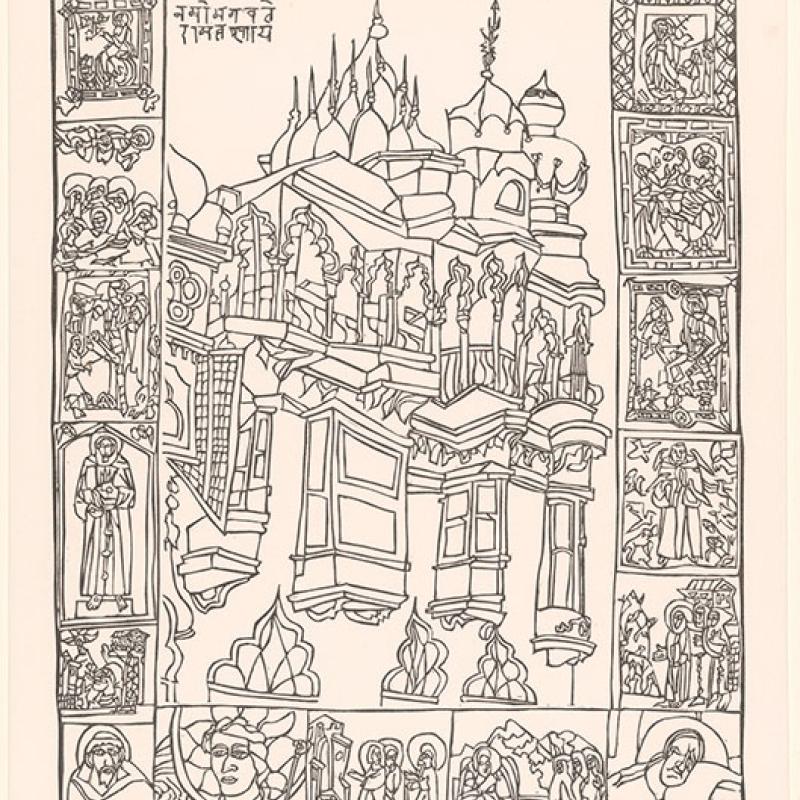

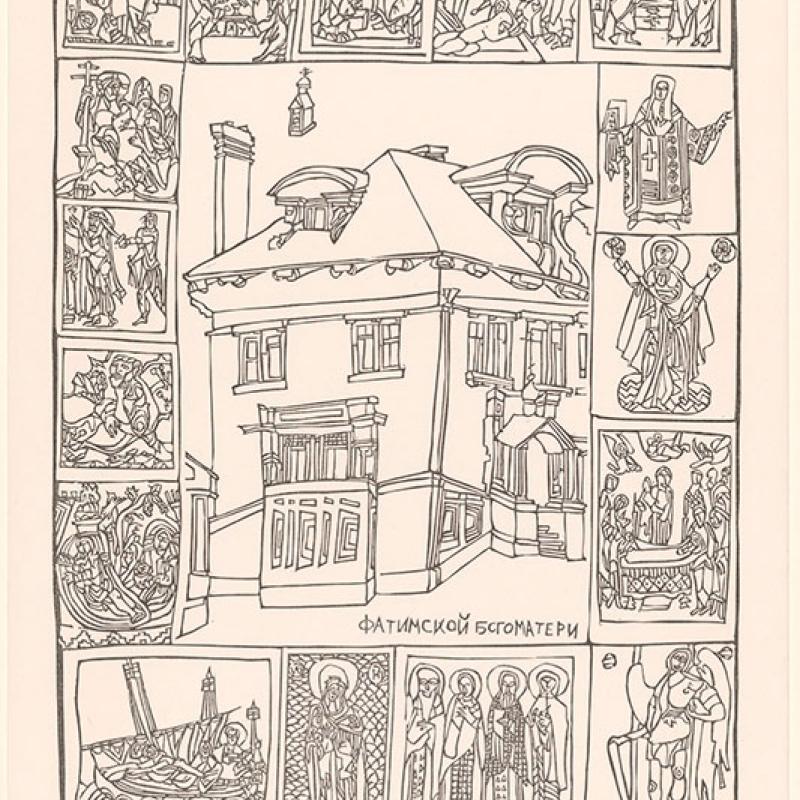

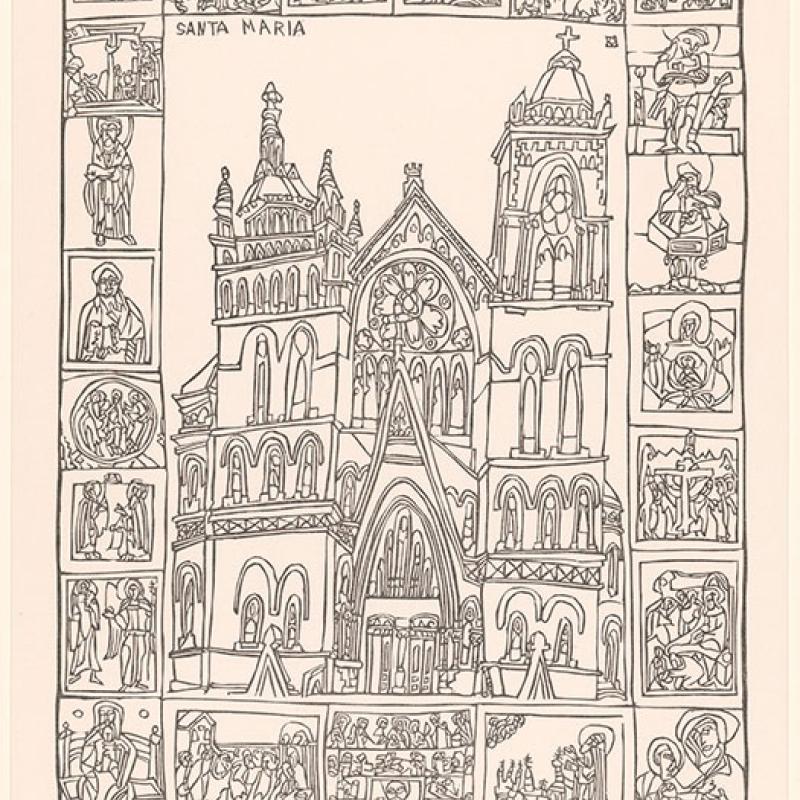

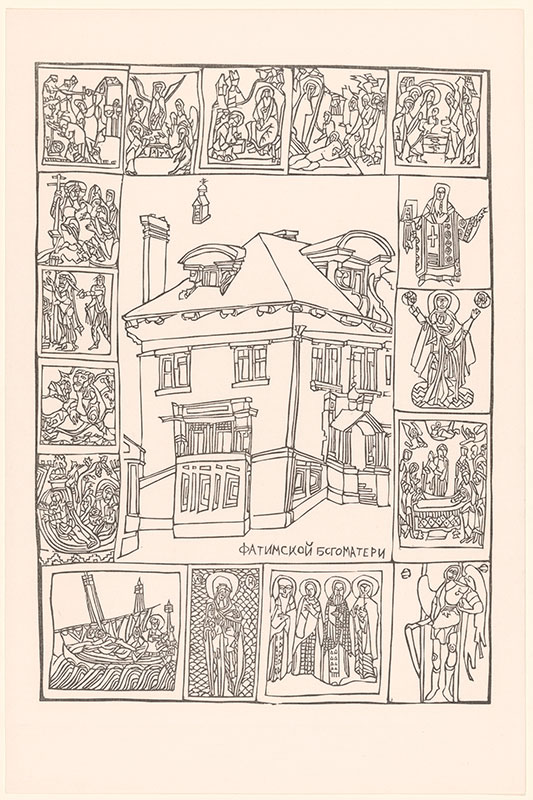

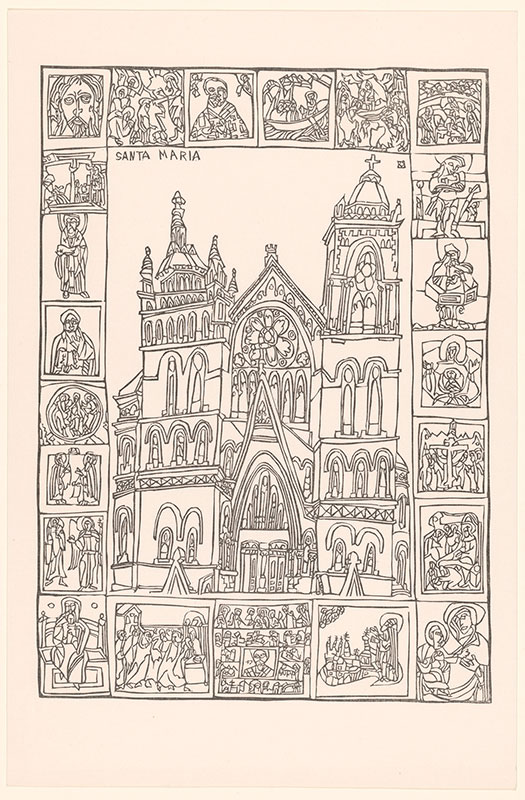

San Francisco Churches, plate 1

Although postwar San Francisco is remembered as a bastion of counterculture, Catholics formed a significant segment of the population, as attested by the abundance of churches. In this portfolio Barton recorded seven houses of worship. Each plate features a building surrounded by saints, angels, and scenes from the New Testament, a format reminiscent of Byzantine icons. Whereas icons typically center on an image of a saint, Barton gave the buildings themselves the place of honor. His approach was clearly expressive rather than exacting, but a colophon naming each church and its intersection reveals Barton’s desire to represent specific structures.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

San Francisco Churches, plate 1: Holy Trinity, Van Ness and Green

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1959

7 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 80

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.335:1

San Francisco Churches, plate 2

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

San Francisco Churches: Our Lady of Kazan, 20th and California

San Francisco: Published at the Porpoise Bookshop, 308 Clement

Street, 1959

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony

San Francisco Churches, plate 5

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

San Francisco Churches, plate 5: Vedanta Temple, Webster near Filbert

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1959

7 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 80

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.335:5

San Francisco Churches, plate 6

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

San Francisco Churches, plate 6: Our Lady of Fatima, 20th and Lake

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1959

7 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 80

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.335:6

San Francisco Churches, plate 7

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

San Francisco Churches, plate 7: St. Mary’s, Van Ness and O’Farrell

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1959

7 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 80

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of William and Norma Anthony; 2017.335:7

Linoleum block for St. Mary’s, Van Ness andO’Farrel

Barton produced all his prints using linoleum blocks such as this one. Henry Evans, who introduced Barton to the form and printed his works, recalled, “I gave [Barton] tools and materials and it was very soon like a re-enactment of the sorcerer’s apprentice. I’d give him a dozen pieces of linoleum on a Friday and Monday he’d show up with them all ready to mount on bases and print.”

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Linoleum block for St. Mary’s, Van Ness and

O’Farrell, plate 7 of San Francisco Churches, 1959

Peregrine Press and Henry H. Evans Collection, William

Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California,

Los Angeles

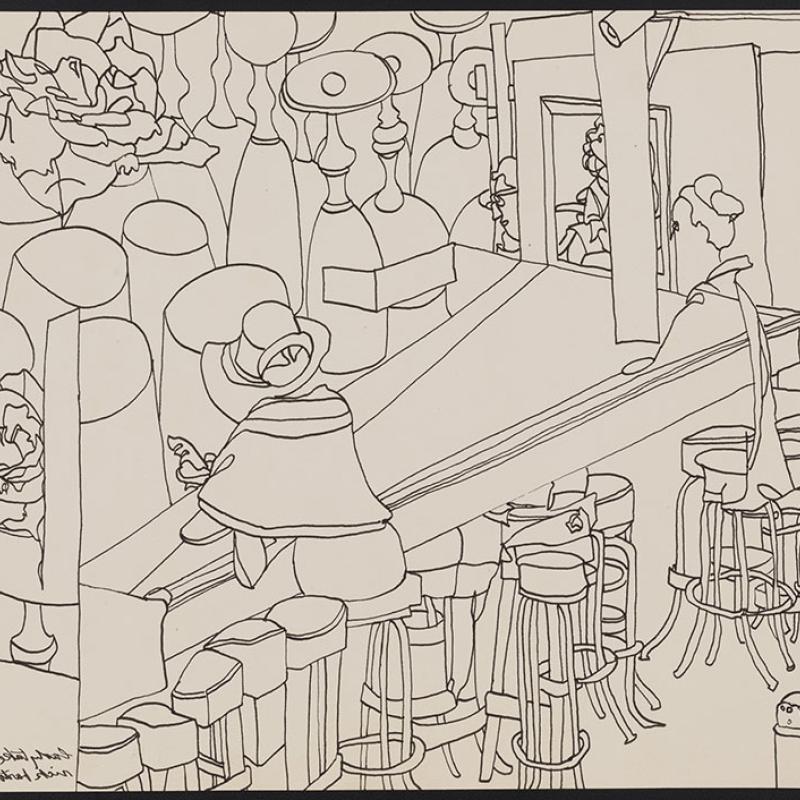

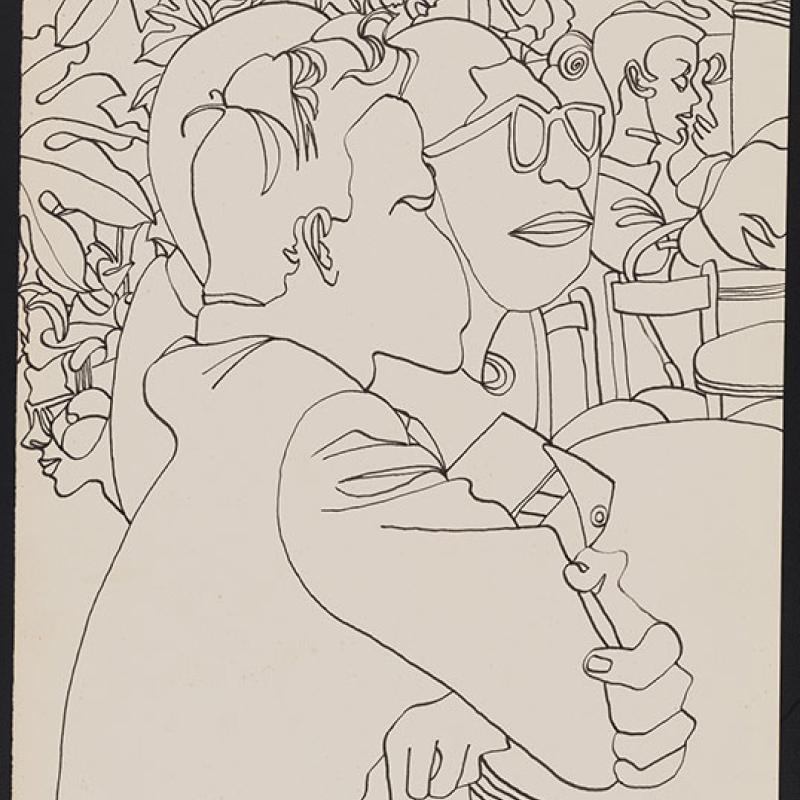

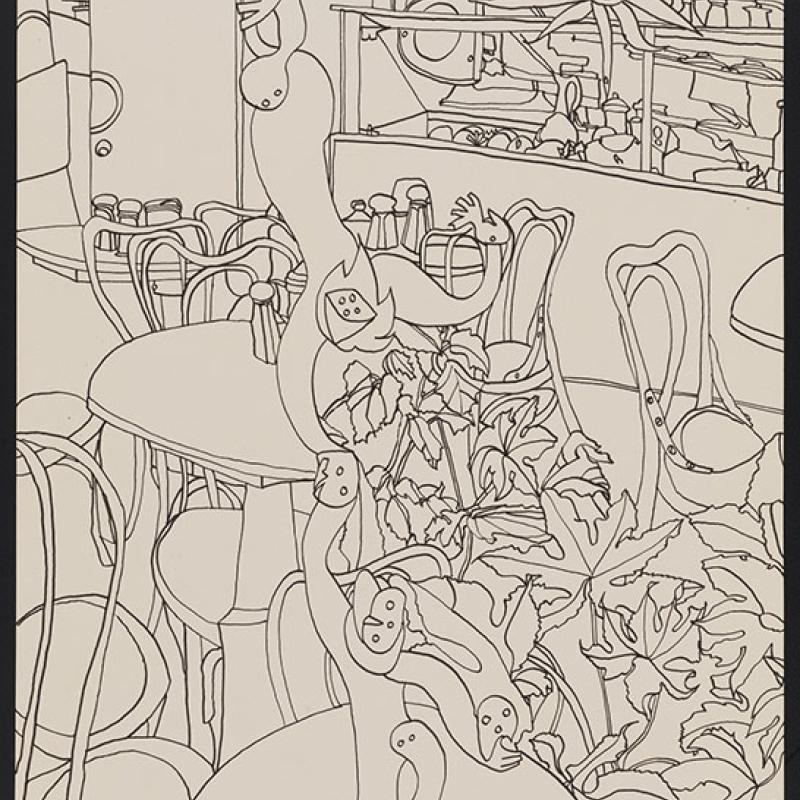

Social Spaces

Cafés and bars were important meeting grounds for artists and poets in San Francisco in the 1950s and ’60s. In both single sheets and elaborate accordionfolded sketchbooks, Barton recorded the atmosphere and denizens of places such as Foster’s Cafeteria, the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, and the Black Cat Café. Barton cultivated a cohort of pupils, whom he called the Academia Vinciana, referencing an informal school of fifteenth-century Milanese intellectuals to which Leonardo da Vinci is thought to have belonged. They gathered in cafés to draw under Barton’s tutelage. Each was encouraged by Barton to purchase a yatate, a portable Japanese writing set that holds a small inkpot and brush. Even when imprisoned on drug charges, as he was on several occasions, Barton drew ceaselessly, conveying the humanity of his fellow inmates.

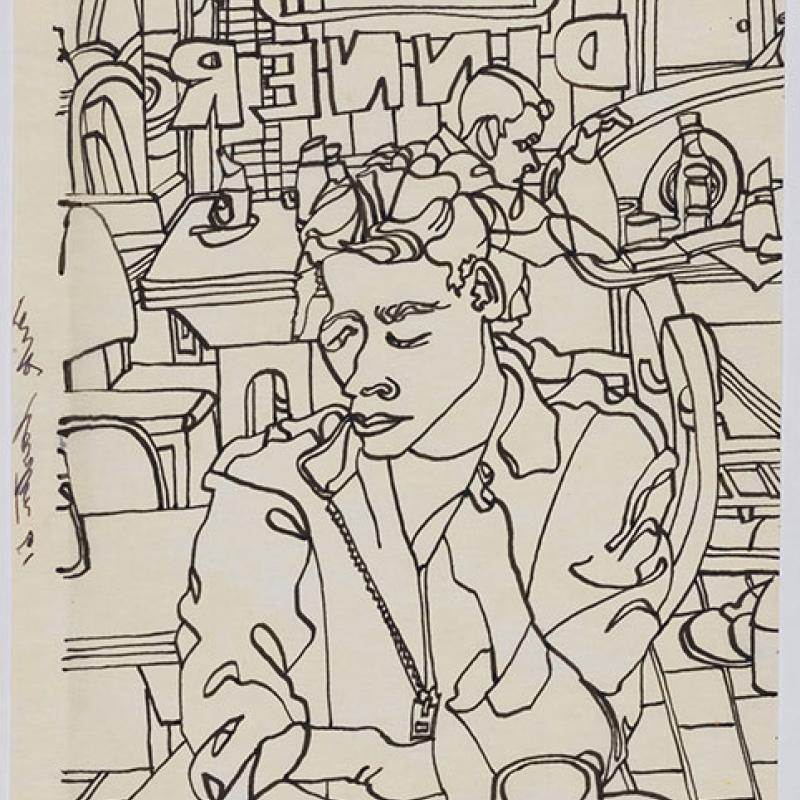

Untitled [Seated man in Foster's Cafeteria]

Foster’s Cafeteria on Polk Street in San Francisco was a popular gathering place for artists and poets. It was located beneath the Wentley Hotel, where poet John Wieners wrote his seminal book, The Hotel Wentley Poems, in 1958. H. D. Moe, another poet who resided in the hotel, remembered Barton as “kind of the philosophical mentor” of a group that spent time in the café below.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Seated man in Foster’s Cafeteria], 1962

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Seated man with book in Foster's Cafeteria]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Seated man with book in Foster’s Cafeteria], 1961

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

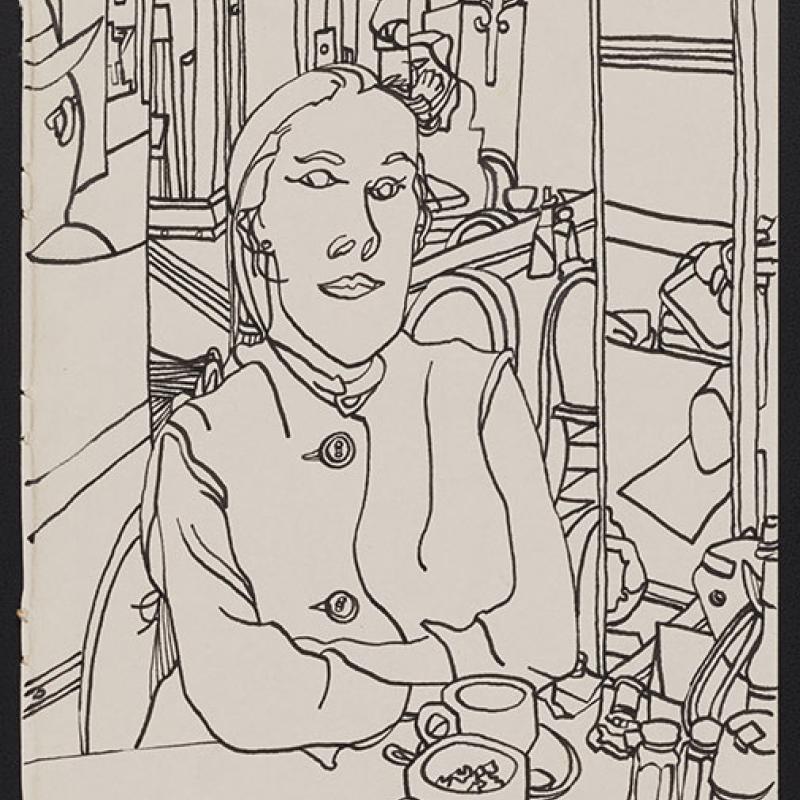

Untitled [Seated woman in Foster's Cafeteria]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Seated woman in Foster’s Cafeteria], ca. 1961–62

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Seated figure in the Black Cat Café]

The Black Cat Café, located at the edge of San Francisco’s North Beach, was a cause célèbre in the fight for gay rights. In the 1940s it became a gathering place for the queer community, attracting the attention of state liquor officials, who often revoked the licenses of gay bars. For nearly fifteen years the Black Cat’s owner fought in court to retain its liquor license. The Black Cat gained additional renown for the popular drag performances of activist José Sarria, who mounted a historic, if ultimately unsuccessful, campaign for a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1961. The accurate portrayal of faces was not one of Barton’s strengths, but this figure, who is absorbed in a book, bears some resemblance to Sarria.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Seated figure in the Black Cat Café], September 27, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

The Black Cat

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

The Black Cat, May 25, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [The Black Cat Café]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [The Black Cat Café], May 9, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

The Bagel Shop

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

The Bagel Shop, May 29, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

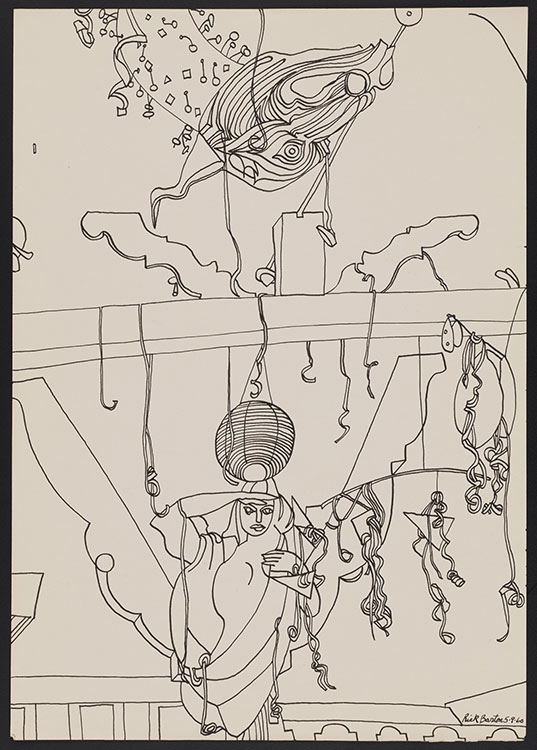

Lady Take Care

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Lady Take Care, May 2, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

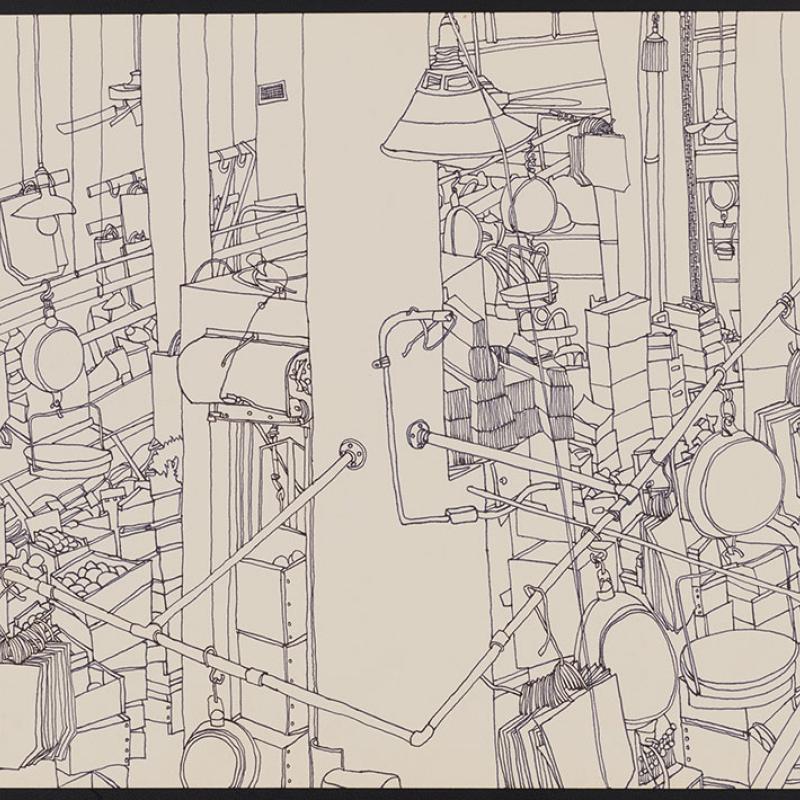

Central Market

In this aerial view of Los Angeles’s Grand Central Market, Barton excludes figures, instead prioritizing lighting fixtures and the scaffold-like structures that support shopping bags and wares. Despite the market’s reputation for crowds, its only inhabitants here are inert objects rendered animate by the energy of Barton’s line.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Central Market, Los Angeles, March 25, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

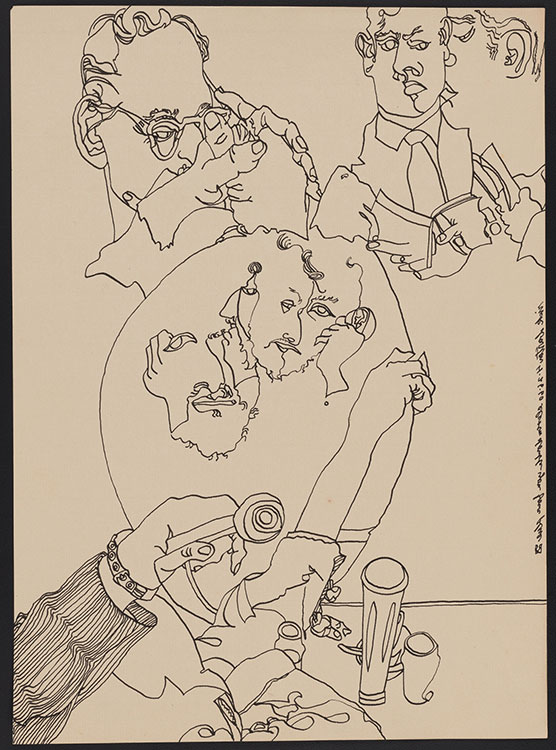

Untitled [Artist and onlookers]

Although the central, bespectacled figure in this small composition does not appear to be the artist himself, the scene does evoke a meeting of what Barton called his Academia Vinciana. David Archer Nelson (b. 1941), a member of this group of largely unknown artists, recollected, “At one time there were half a dozen of us or more, in North Beach, all using yatates, painting at café tables. We often sat at the same tables working together, Barton of course holding court.” Nelson also recalled that when Barton, a voracious reader, encountered a similarly erudite interlocutor, they would argue “beautifully in the Socratic style.”

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Artist and onlookers], 1961

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Eleven Double You Four Plus

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Eleven Double You Four Plus, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

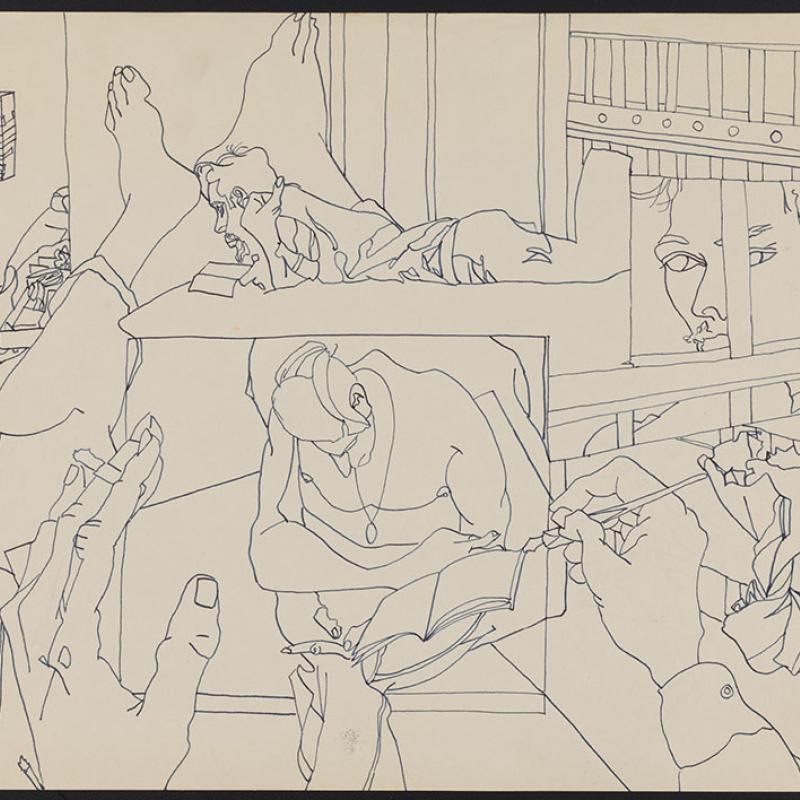

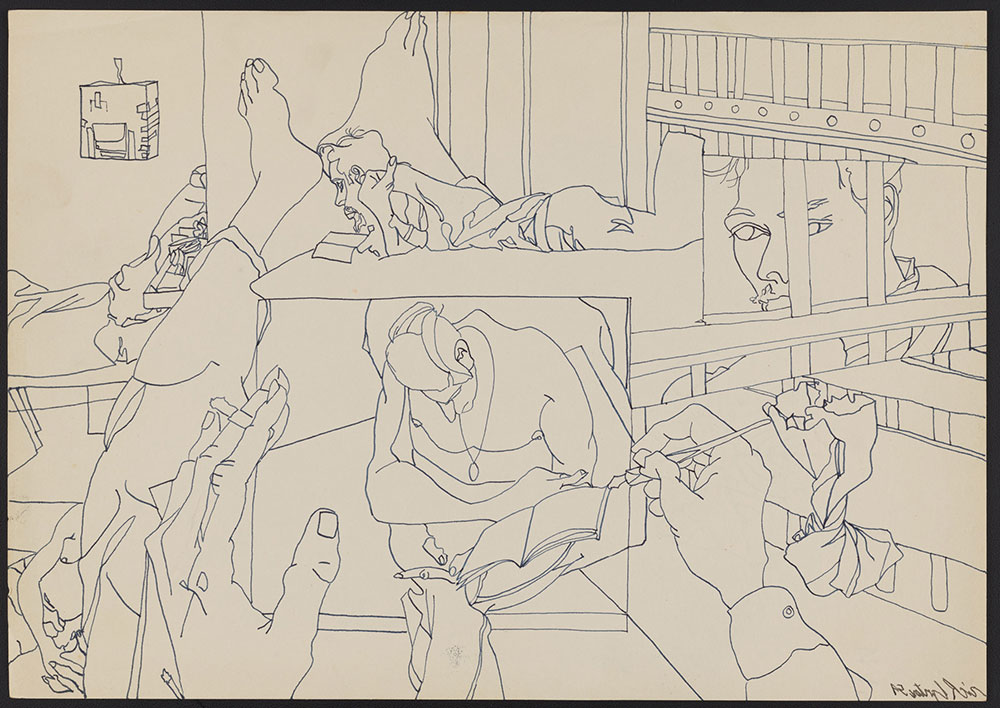

Untitled [Inmates reading]

In July 1959, a Sausalito newspaper reported that Barton had been arrested on a charge of “furnishing narcotics.” Just a few weeks earlier, the same newspaper had announced an exhibition of his drawings at the Tides Bookstore. While in prison that year, Barton made this metacomposition of the artist sketching his fellow inmates, as well as the drawings nearby. In these works, as in drawings made during later periods of incarceration, Barton portrays his cellmates as sensitive souls.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Inmates reading], 1959

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Reclining inmates]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Reclining inmates], 1959

Graphite and red ballpoint pen

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Inmates]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Inmates], 1959

Red and blue ballpoint pen

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

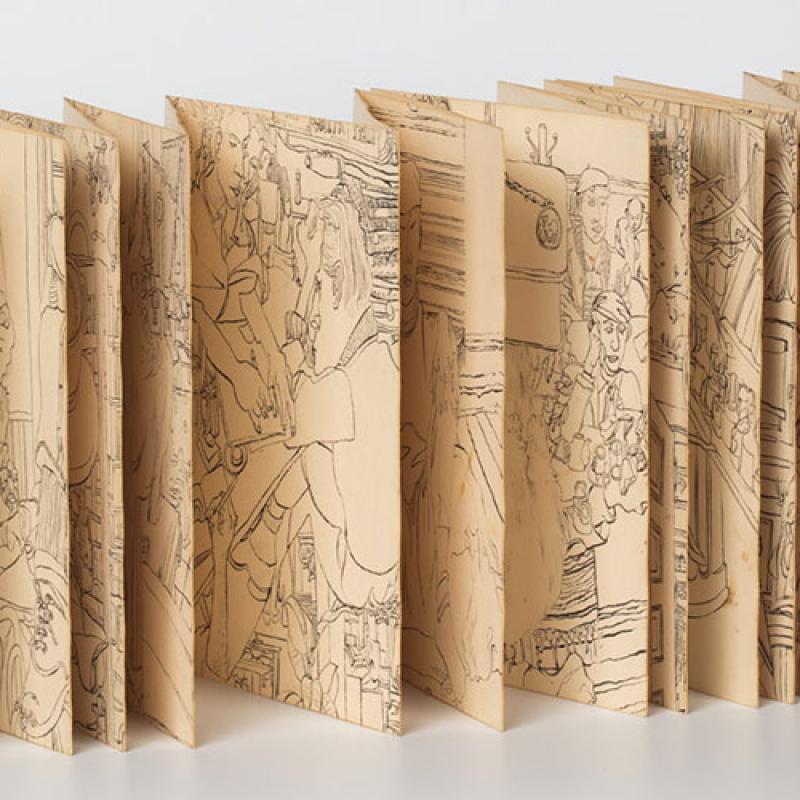

Untitled sketchbook, 1961

Barton probably made dozens of books like the two shown here throughout his life. The accordion format allowed him to create continuous images over time, multiplying his connections in a web-like style that conflates drawing and writing. Completed between 1959 and 1962, all thirteen of Barton’s known sketchbooks reside at Northwestern University Libraries, ten of them accordion style.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled sketchbook, 1961

Brush and ink on accordion-folded book

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries; MS 125

Untitled sketchbook, 1962

Barton’s preferred format when working in cafés such as Foster’s Cafeteria was the accordion-folded book, in which he painted using a yatate, comprising a brush and portable inkpot. Artist and poet Etel Adnan (1925–2021), who met Barton in the early 1960s, credited him with introducing her to this format:

Before that fateful afternoon, I had never seen any folding books. He opened the one he was working on, put it on the table after having pushed his drink and dried the surface, and I was in a state of wonder: tiny heads were drawn, each with its own character, the customers of the café were recorded with the utmost care, filling every page of the book the way they were crowding the place as well as Rick’s mind. Here

and there, tucked in what were empty places on the paper, were fingers holding cigarettes, swirls of smoke, an obsessed and obsessive mass of humanity running like a river all along the book which was so to speak growing in length, like a ribbon. Thus one of the

most lasting of my artistic impressions was happening amidst a crowd in the magic atmosphere of a San Francisco which was still primarily a harbor with all the feelings of alcohol and transiency that harbors create.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled sketchbook, 1962

Brush and ink on accordion-folded book

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries; MS 95e

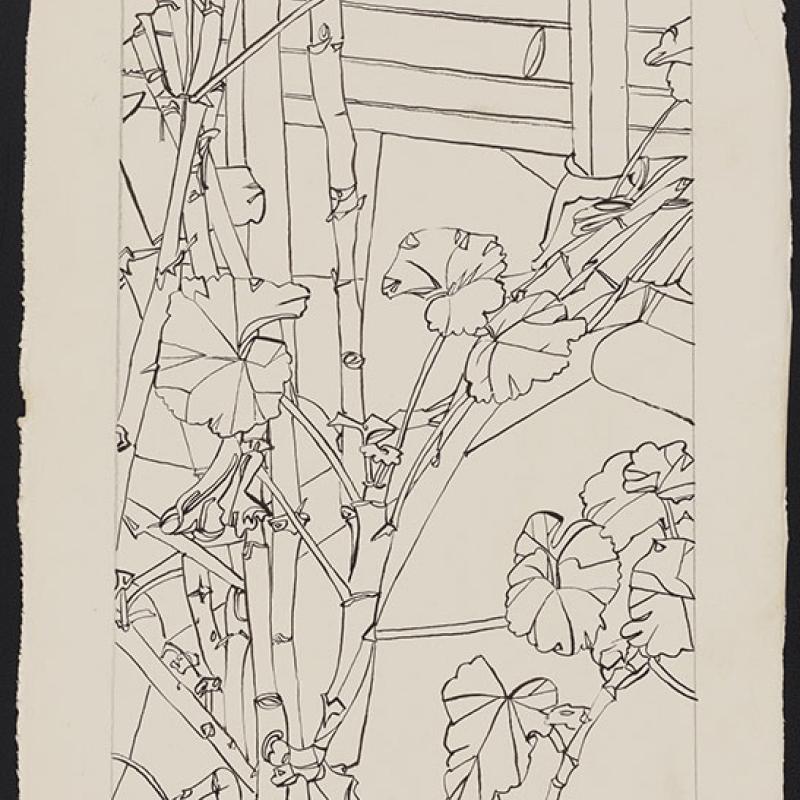

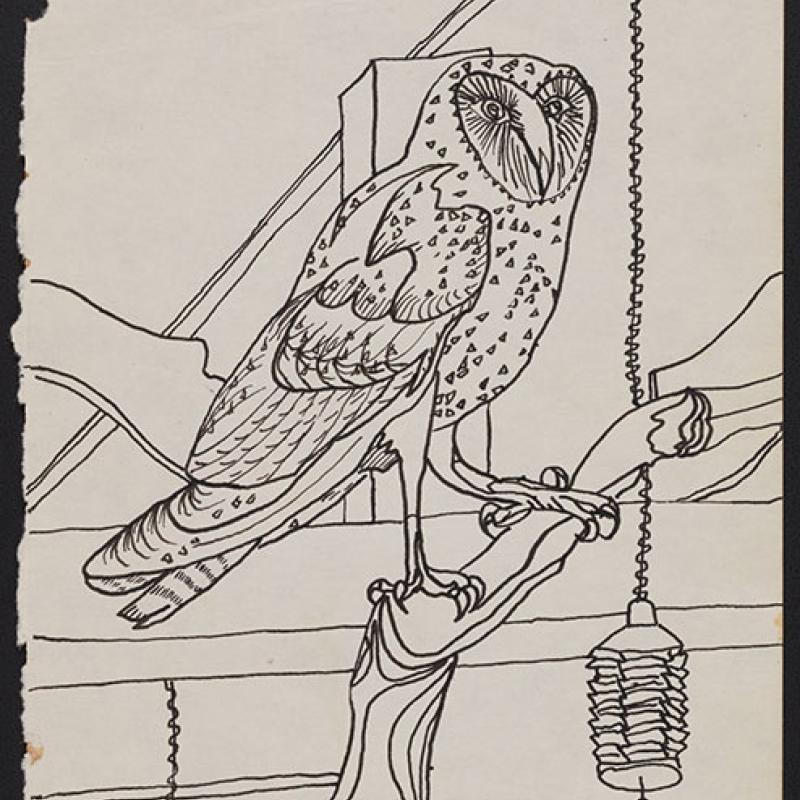

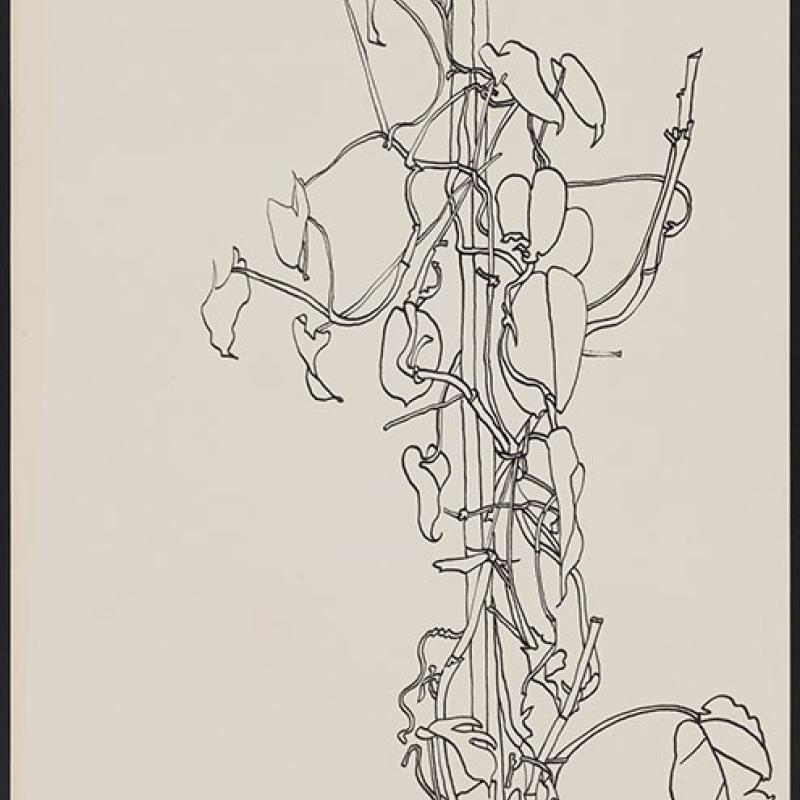

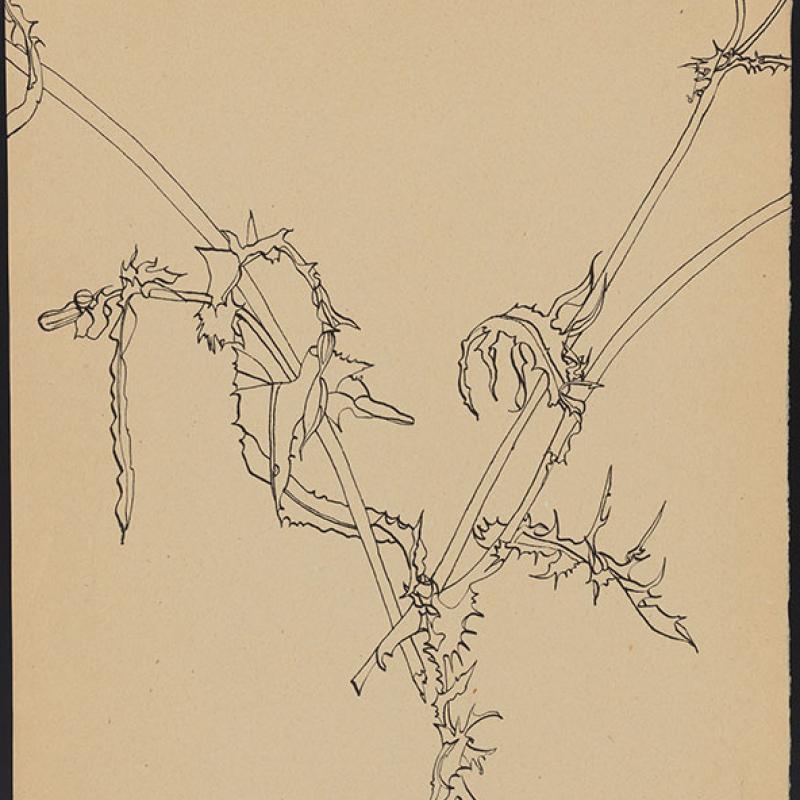

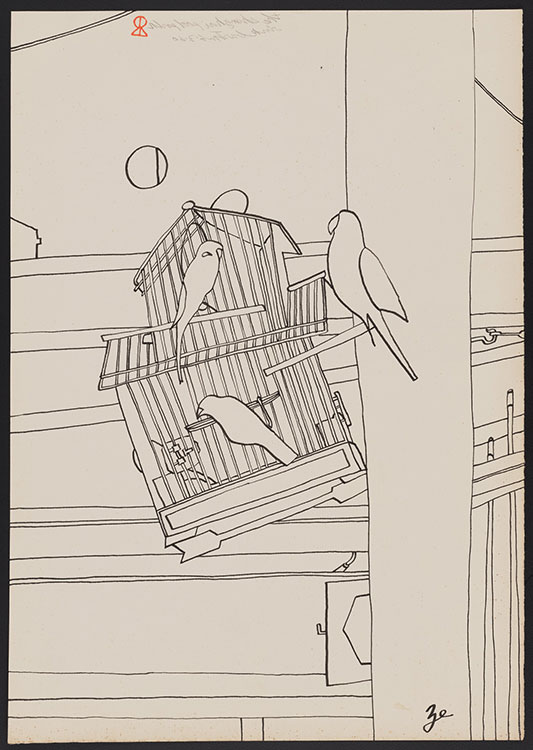

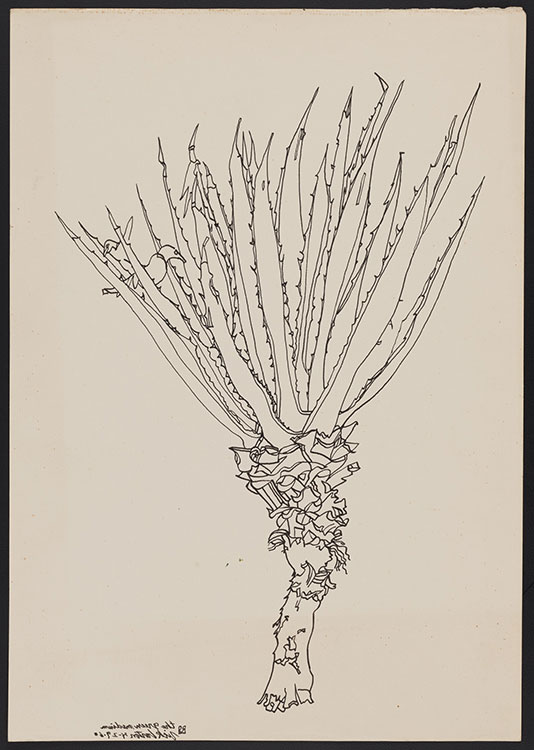

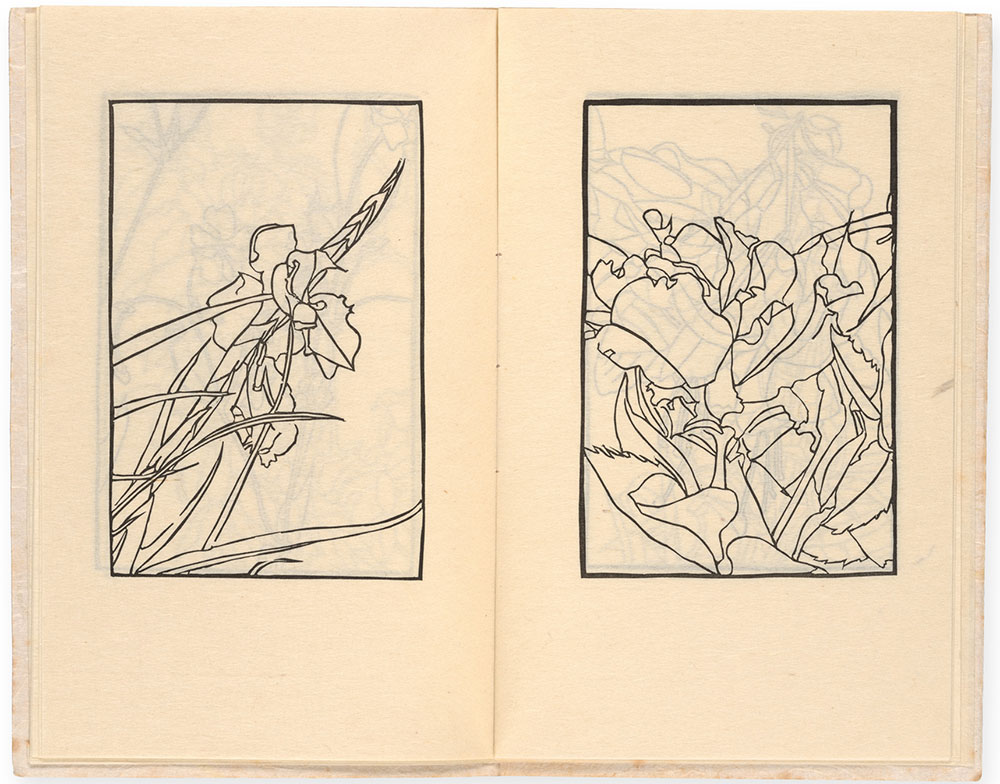

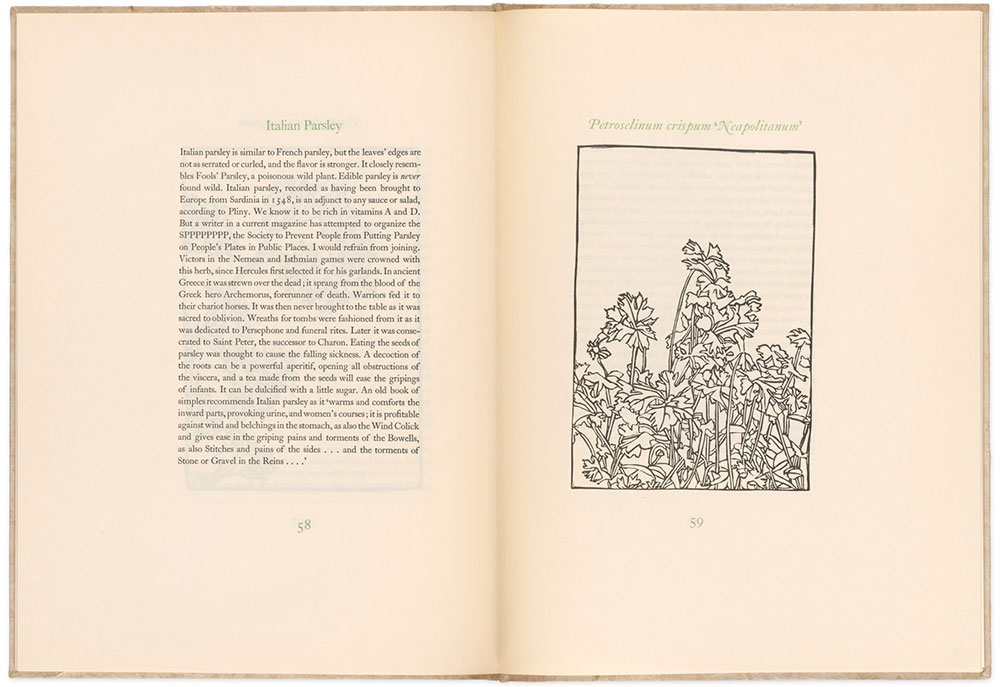

Flora and Fauna

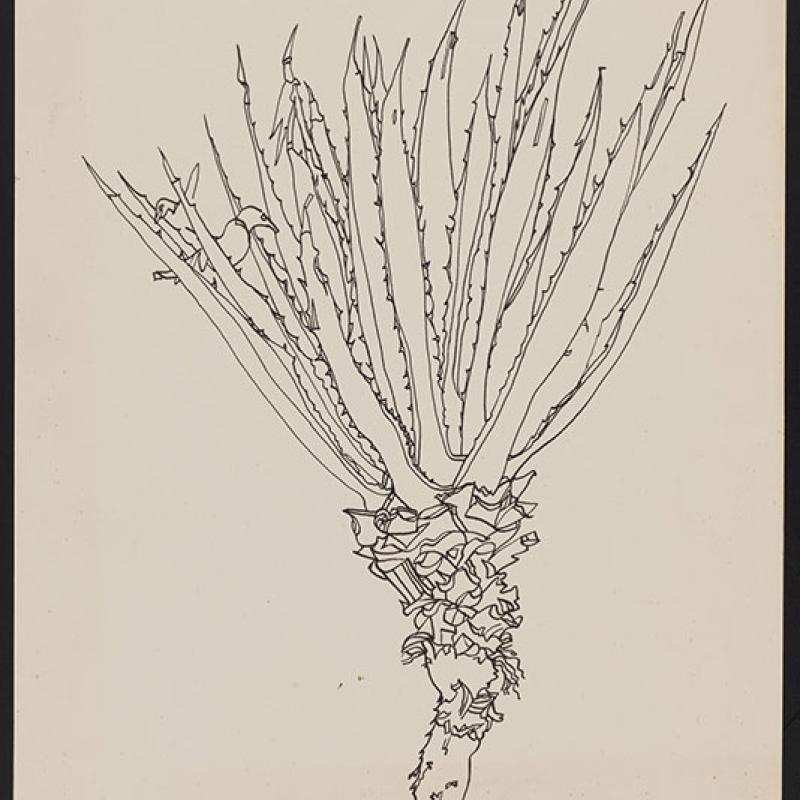

Wherever he went, Barton took note of the plant life around him, also casting his eye on birds, fish, and other small, domestic creatures. His passion for plants was shared by Henry Evans, who made his own botanical prints, and Evans’s wife Patricia, with whom Barton collaborated on the volume A Modern Herbal (1961). Whether tracing a common houseplant or an exotic bloom, Barton’s sinuous line was perfectly suited to the visual description of botanical specimens.

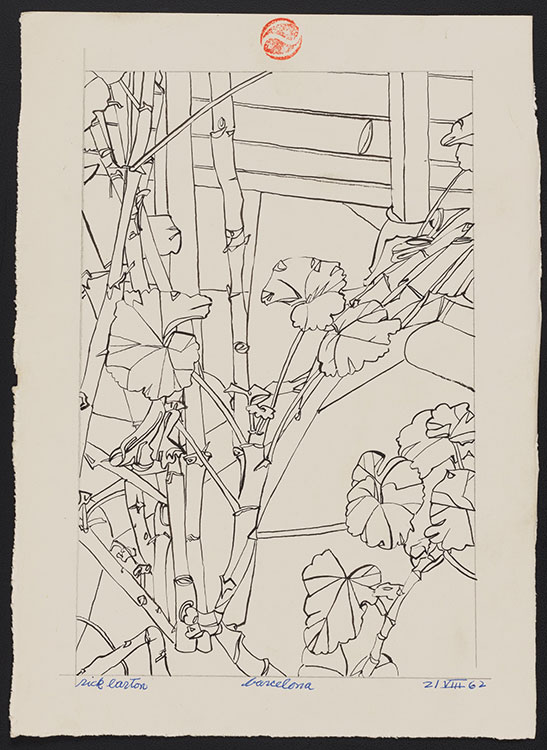

Barcelona, August 21, 1962

This elegant drawing, featuring one of Barton’s customized stamps at the top, illustrates his predilection for plant life. Although such works recall the spare botanical drawings of Henri Matisse (1869–1954), with whom he was certainly familiar, Barton developed an idiosyncratic repertoire of marks, such as those that denote the nodes of the central stem.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Barcelona, August 21, 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Owl] 1962

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Owl] 1962

Pen and ink with graphite

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

The Shanghai Pool Parlor

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

The Shanghai Pool Parlor, June 3, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Hands and fish]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Hands and fish], October 18, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

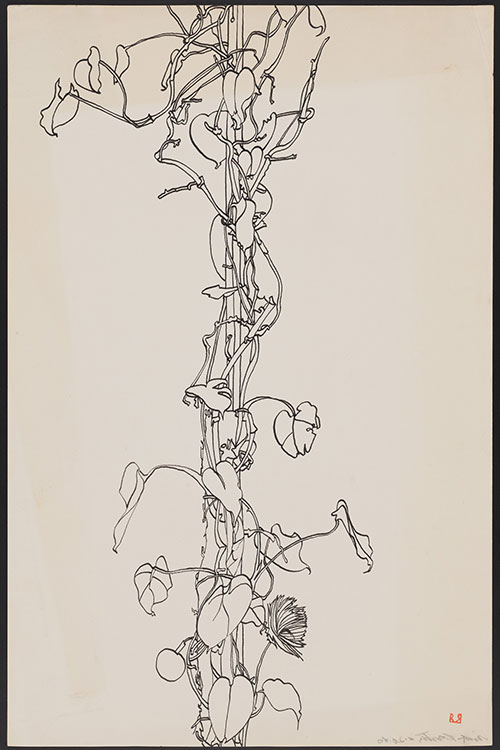

Untitled [Plant with garden stick, top and bottom]

Although each of these sheets is signed and dated, suggesting that the drawings are autonomous, they also form halves of a pair. The two works can be hung together, as they are here, resulting in a more imposing composition.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Plant with garden stick, top and bottom], June 26, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Stems]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Stems], June 23, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

The Green Medium

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

The Green Medium, April 29, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

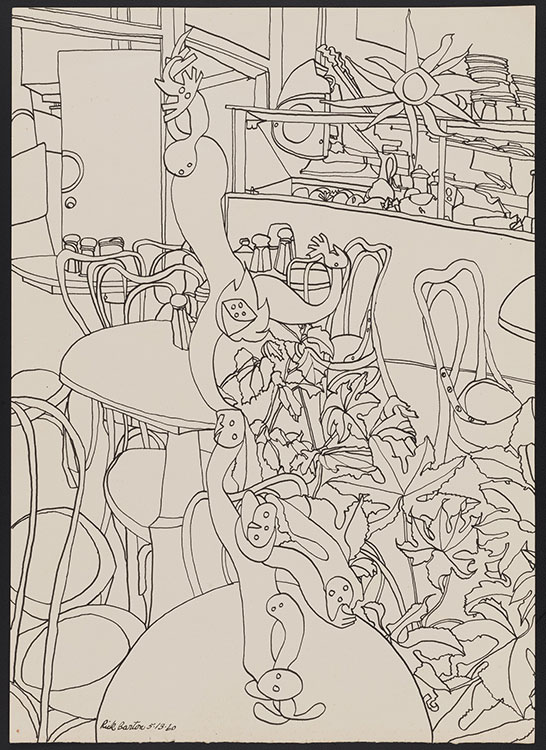

Untitled [Plant on restaurant table]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Plant on restaurant table], May 13, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Untitled [Plant in bedroom]

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Untitled [Plant in bedroom], May 15, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

Chinese Ink

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Chinese Ink, April 1, 1960

Pen and ink

Rick Barton papers (Collection 2374), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles

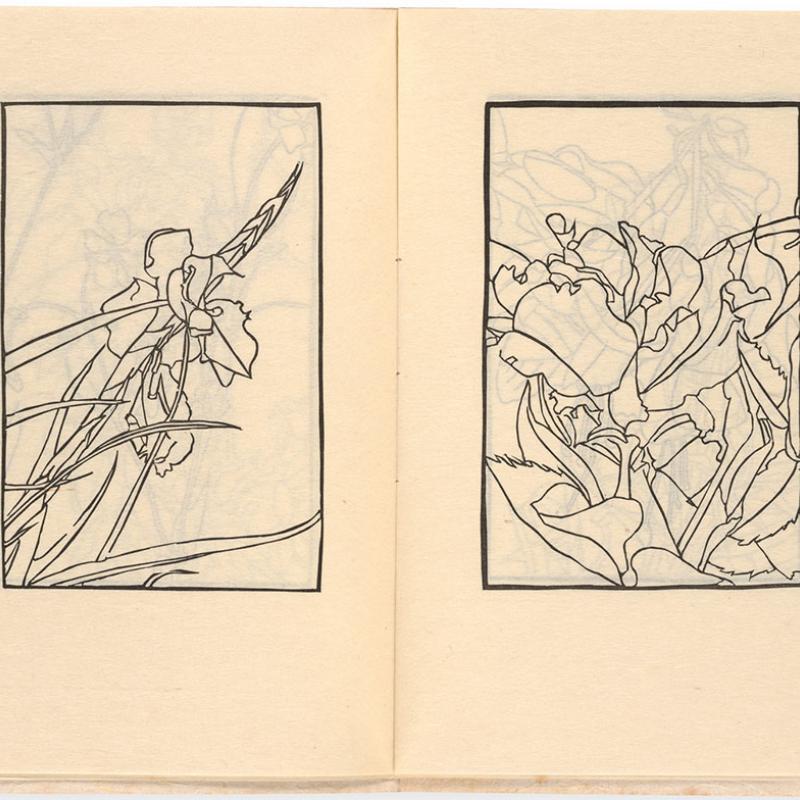

Flowers, a First Coloring Book

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Flowers, a First Coloring Book

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1960

24 linoleum block prints on double leaves, edition of 80

Private collection

A Modern Herbal

Barton had a close relationship not only with Henry Evans but also with Evans’s first wife, Patricia, who authored this twentieth-century update on a classic genre. Barton’s illustrations demonstrate his familiarity with his subjects, as well as his skill in representing flora both accurately and economically.

Patricia Evans (1920–1988)

A Modern Herbal

Illustrations by Rick Barton

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1961

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Gordon N. Ray Fund, 2021; PML 198663

Hands and Flowers

This portfolio combines two of Barton’s favorite subjects, hands and flowers. He privileges them equally, resulting in inventive compositions that seem to imagine a species that is both human and botanical.

Rick Barton (1928–1992)

Hands and Flowers, plates 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6

San Francisco: Porpoise Bookshop, 1960

11 linoleum block prints in portfolio, edition of 80

Private collection