Gwendolyn Brooks: A Poet’s Work in Community

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), one of the most prolific American poets of the twentieth century, was the first Black author to win a Pulitzer Prize in any category. Her career was marked by both her work’s accessibility and her concerns for social justice. Over more than five decades, Brooks’s connections to her community deepened along with her involvement in the international struggles against anti-Black racism, expanding the scope of her poetry and her influence on other artists and writers. She forged relationships with members of the Black Arts movement, the Black Power movement’s aesthetic counterpart, to advance work that speaks directly to the needs, hopes, and dreams of Black people. Brooks also collaborated with Black publishers of the 1960s and ’70s, dedicating herself to cultivating future writers. These exchanges opened up surprising spaces of teaching, learning, and empowerment. Objects on view in the gallery, some of which are drawn from Brooks’s personal library, reflect her roles as a poet, friend, and mentor, revealing the essential links between community and creative growth.

Unless otherwise noted, all objects are in the collection of the Morgan Library & Museum.

This online exhibition is presented in conjunction with the exhibition Gwendolyn Brooks: A Poet’s Work in Community on view January 28 through June 5, 2022, organized by Nicholas Caldwell, Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellow, Department of Printed Books & Bindings.

Gwendolyn Brooks: A Poet’s Work in Community is made possible by Katharine J. Rayner, with generous support from the Caroline Morgan Macomber Fund.

Overview

Gallery Images

A Poet in Bronzeville

Gwendolyn Brooks was born in 1917 in Kansas to David Anderson Brooks, a custodial worker, and Keziah Brooks, a schoolteacher. Shortly after Gwendolyn’s birth, her parents moved the family to Chicago, where she would reside for the rest of her life. Raised in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville, Brooks started exploring creative writing at a young age. She kept a poetry journal from the age of eleven, and by the time she turned thirteen, her poems were being published in a local newspaper as well as a national magazine, American Childhood. Quiet by nature, a young Brooks used poetry to speak the truths that her family, experiences, and surroundings taught her. She found those surroundings to be a rich subject for her poems.

Gwendolyn Brooks was born in 1917 in Kansas to David Anderson Brooks, a custodial worker, and Keziah Brooks, a schoolteacher. Shortly after Gwendolyn’s birth, her parents moved the family to Chicago, where she would reside for the rest of her life. Raised in the South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville, Brooks started exploring creative writing at a young age. She kept a poetry journal from the age of eleven, and by the time she turned thirteen, her poems were being published in a local newspaper as well as a national magazine, American Childhood. Quiet by nature, a young Brooks used poetry to speak the truths that her family, experiences, and surroundings taught her. She found those surroundings to be a rich subject for her poems.

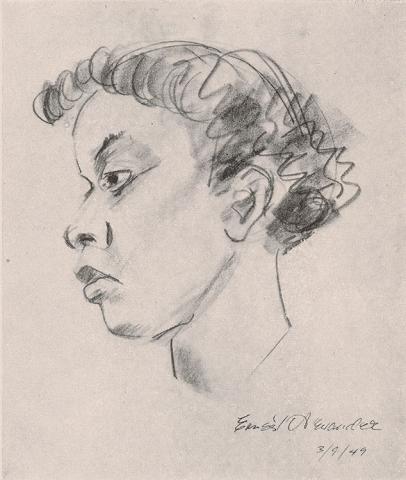

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Annie Allen

Frontispiece by Ernest Alexander (1921–1974)

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184291

Used with the permission of the Estate of Ernest Alexander.

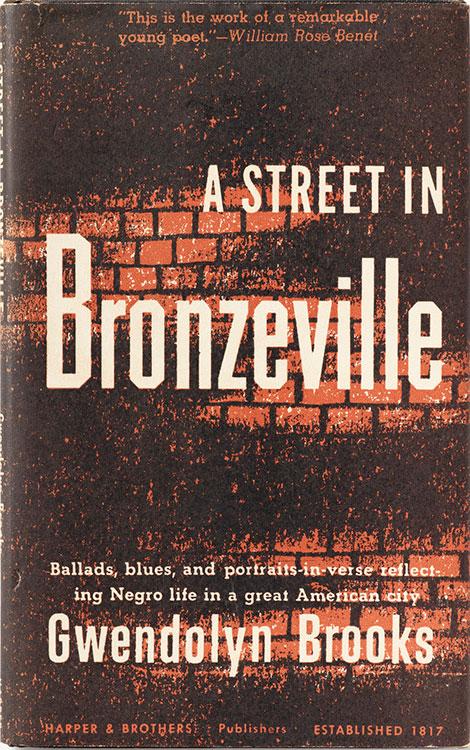

A Street in Bronzeville

If you wanted a poem, you had only to look out of a window. There was material always, walking or running, fighting or screaming or singing.

—Gwendolyn Brooks

Brooks’s first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, was influenced by the people that she connected with and observed on the streets of her neighborhood in Chicago. In these poems, Brooks portrays scenes of urban Black daily life, a topic that was otherwise ignored in popular writing at the time. Her subjects are the preacher, the working woman, the married couple, the schoolgirl. Brooks’s empathetic treatment of the day-to-day lives of African American people, from dealing with systemic racism and poverty to celebratory moments of joy and love, paints intimate and relatable portraits of her community.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

A Street in Bronzeville

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1945

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184293

"We're the Only Colored People Here"

“We’re the Only Colored People Here” was printed in the inaugural volume of Black Sun Press’s Portfolio: An Intercontinental Quarterly. Brooks’s short story, excerpted from the manuscript that would become the novel Maud Martha (1953), is told from the perspective of a couple attempting to enjoy a night at the theater despite the uncomfortable reality alluded to in the title. Created by Caresse Crosby, an American expatriate and publisher in Paris, as an “exchange of thought between America and Europe,” Portfolio showcased avant-garde writers and artists. Notably, Brooks was the only Black writer whose work was featured in the volume, alongside that of Henry Miller, Kay Boyle, Karl Shapiro, and others.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

“We’re the Only Colored People Here”

Portfolio: An Intercontinental Quarterly 1 (Summer 1945)

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 182562.1

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

Annie Allen

Brooks made history in 1950 by becoming the first African American recipient of a Pulitzer Prize. Annie Allen, the winning book of poetry, tells a story in three parts of a young African American woman coming into adulthood during World War I. With formal and technical precision, Annie Allen explores the title character’s struggles with love, loss, and growing up, casting them in an epic light. The frontispiece, a soft rendering of the poet’s profile by her friend Ernest Alexander, may have been the first likeness of Brooks that readers had seen. The novel Maud Martha follows themes similar to those in Annie Allen: though the former is Brooks’s sole work of fiction, both books are partly autobiographical.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Annie Allen

Frontispiece by Ernest Alexander (1921–1974)

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949

Used with the permission of the Estate of Ernest Alexander.

Maud Martha

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 184291, PML 184292

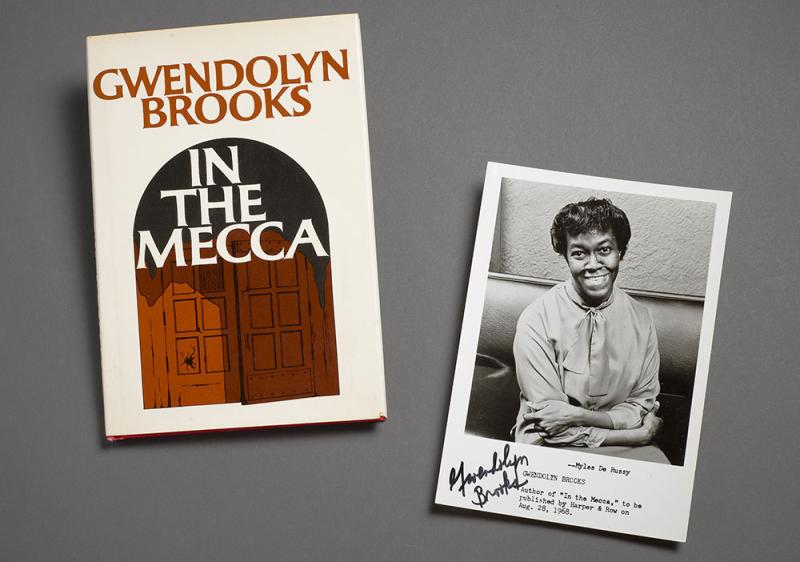

In the Mecca

In 1967 Brooks’s participation at the Black Writers’ Conference at Fisk University made an indelible impact on her. Among the other speakers was Amiri Baraka, a vocal member of the Black Arts movement whose poetry raged against oppression. He joined like-minded poets in writing exclusively and directly to a Black audience, creating a sense of fellowship, instilling the power of self-determination, and rejecting racist institutions. Conversation at Fisk revealed to Brooks the possibilities of liberation in Black solidarity, and she would return home and do what she did best: write. In the Mecca centers on the Mecca Flats apartment complex in Chicago but also expands beyond it, connecting the disillusioned inhabitants of the dilapidated building to people suffering the conditions of racism everywhere.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

In the Mecca

New York: Harper & Row, 1968

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198679

A Black Arts Community Leader

The Black Arts Movement initiated a radical shift from the predominantly White mainstream art world, allowing Black artists to create their own institutions and metrics for what was considered art. The movement introduced a visual language that emphasized Black cultural history and celebrated Afrocentric imagery. In the 1960’s and 70s, Gwendolyn Brooks found alignment with this large artistic and political community.

The Black Arts Movement initiated a radical shift from the predominantly White mainstream art world, allowing Black artists to create their own institutions and metrics for what was considered art. The movement introduced a visual language that emphasized Black cultural history and celebrated Afrocentric imagery. In the 1960’s and 70s, Gwendolyn Brooks found alignment with this large artistic and political community.

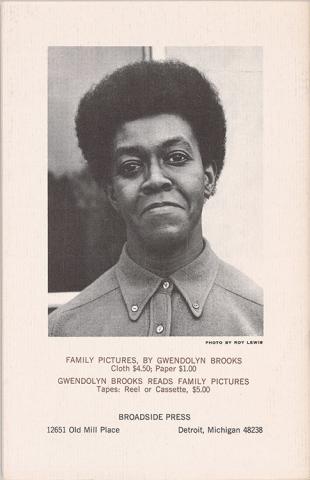

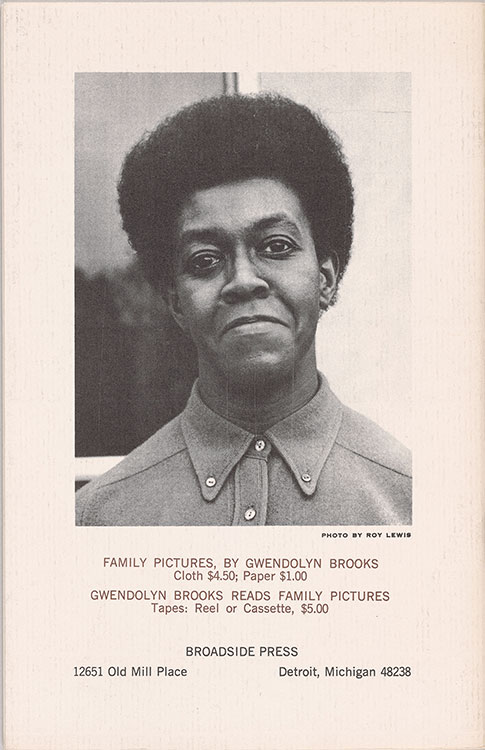

Back cover of Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), Family Pictures (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970)

Photograph by Roy Lewis (b. 1937)

The Morgan Library & Museum, PML 198515.

© Broadside Lotus Press

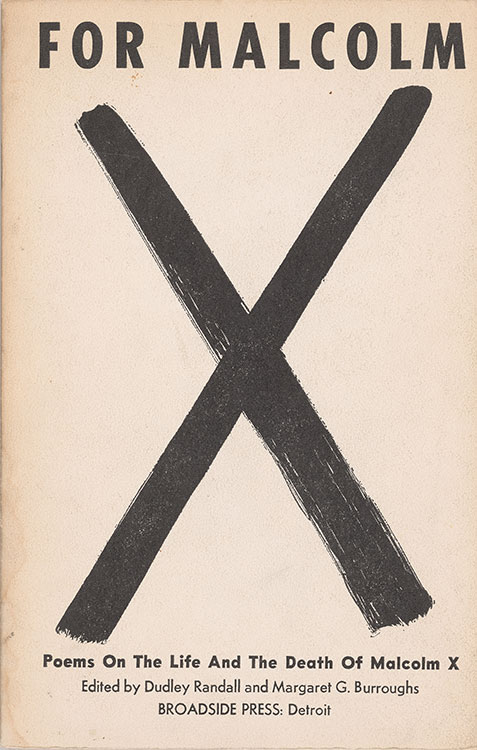

For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X

It is the task or job or responsibility or pleasure or pride of any writer to respond to his climate.

—Gwendolyn Brooks

The 1960s assassinations of two great African American leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, mobilized the Black Power movement, an international campaign against anti-Black racism. Brooks, like many Black writers, felt the need to address these tragedies and their repercussions. The Black-owned Broadside Press responded to that need, publishing work that emphasized issues of identity, cultural history, racial justice, and community uplift. Broadside’s first book of poems, For Malcolm, provided a space for Black authors to speak about the life, work, and death of the prominent leader.

For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X

Edited by Dudley Randall (1914–2000) and Margaret G. Burroughs (1915–2010)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1967

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198544

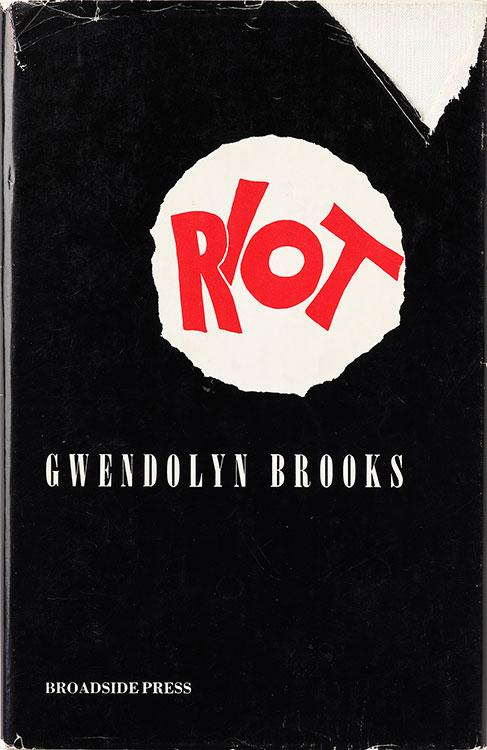

Riot

Reflecting her newly urgent interest in racial consciousness, Brooks changed publishers in 1970, switching from the major press Harper & Row to the small, new Broadside Press. “Everyone who’s black,” she said, “ought to have a black publisher.” In Riot, her first book of poetry released by Broadside, Brooks documents reactions of the global Black community to the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Working with Broadside gave Brooks more freedom to speak directly to Black audiences. In return for this freedom, she donated all royalties from Riot back to the press. With Brooks’s backing, Broadside became a central asset to the Black Arts movement. Known today as Broadside Lotus Press, it is one of the oldest Black-owned US publishers still in operation.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Riot

Design by Cledie Taylor (b. 1926)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198519

© Broadside Lotus Press

Riot

A riot is the language of the unheard.

—Martin Luther King Jr., epigraph of Riot

A poem in three parts, Riot, like 1968’s In the Mecca, is more experimental and directly political than Brooks’s early work. Allah Shango, the frontispiece by AfriCOBRA cofounder Jeff Donaldson, shows two young men behind a sheet of glass. One holds a long African statuette and seems poised to smash it through the invisible barrier at any moment. The text of Riot announces that young Black people are prepared literally to fight back against oppression. Its design was meant to unsettle any White audiences and proclaim Black cultural authority.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Riot

Frontispiece by Jeff Donaldson (1932–2004)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198520

The Estate of Jeff Donaldson, courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York. © Broadside Lotus Press

"We Real Cool"

The creators of the Black Arts movement wanted to reach the widest possible Black audience. To do so, writers had to “bring poetry to the people,” wherever they were. It was with this in mind that Broadside Press launched its Broadside Series, printing single poems on sheets of paper with eye-catching designs. Often sold for a few cents, these sheets were meant to be passed around, hung up, and pasted on city walls. The ethos of this format, which made poetry accessible at minimal cost, also inspired the press’s name. When publisher Dudley Randall started the series, he asked Brooks if she would contribute a poem. Brooks replied, “You can use any poem I have,” resulting in this striking print of her 1960 work “We Real Cool,” designed by Cledie Taylor.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

“We Real Cool”

Design by Cledie Taylor (b. 1926)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1966

Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Call no. Broadside Ludwig 461. Reprinted by Consent of Brooks Permissions

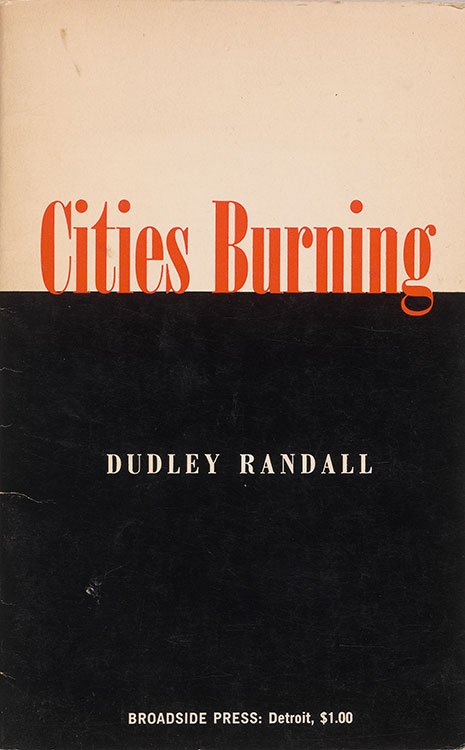

Cities Burning

Created by the Black poet Dudley Randall in 1965 without any blueprint, savings, or investors, Broadside Press survived and grew through the support of Black artists and its international Black readership. In the press’s early years, Randall and his associates worked out of a single room in his home. The first publications were high quality but produced in relatively small numbers, which allowed them to be printed quickly and at a low cost. Like the press’s broadside poems, the covers of its books featured bold designs by Black artists. Randall also used Broadside to print his own work, which mainstream publishers had refused due to its subject matter, including discussions of state violence and the need for new representations of Black life.

Dudley Randall (1914–2000)

Cities Burning

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1968

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198554

© Broadside Lotus Press

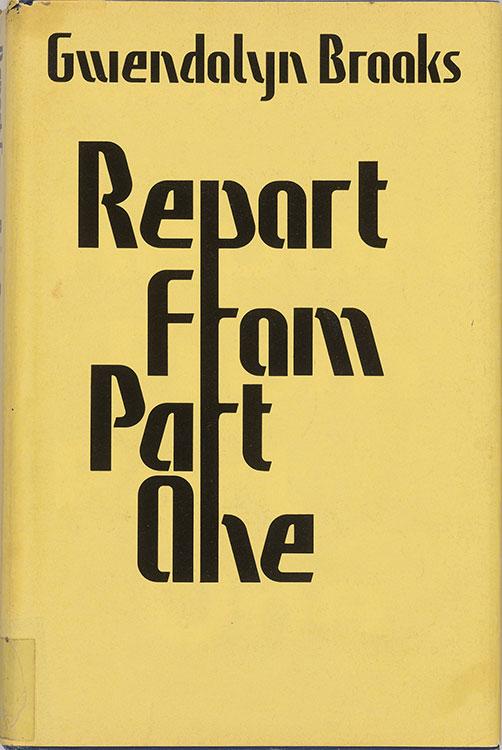

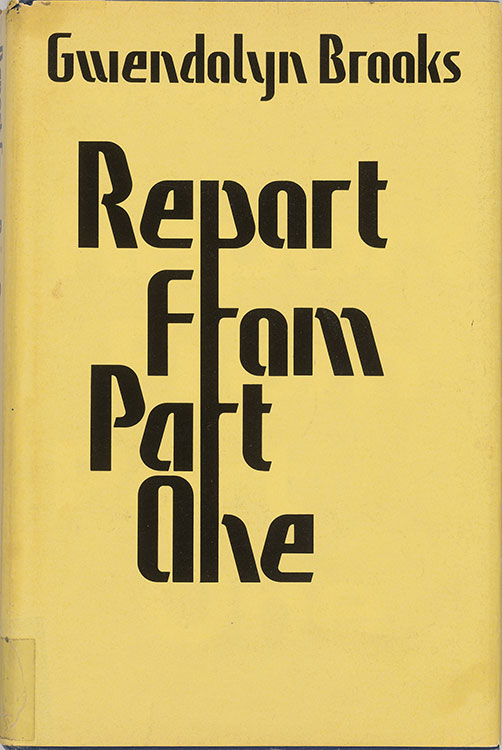

Report from Part One

When Brooks developed her first memoir project, Report from Part One, she insisted that it be printed by Broadside Press. The result was an experimental book containing interviews, letters from the poet’s parents and children, and approximately eighty photographs—personal family pictures as well as snapshots of collaborators, colleagues, neighbors, and other community members, many taken by photographer Roy Lewis. Brooks dedicated the book to these friends and fellow Black artists who fed her creativity and work. The inclusion of these names and photos in Brooks’s memoir shows how integral community was in her life, introducing a collective impulse into the tradition of autobiographical writing.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Report from Part One

Photographs by Roy Lewis (b. 1937) and others

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1972

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198522

Think Black

Brooks proclaimed that a younger generation of artists—including Knight, Sanchez, Madhubuti, and Giovanni—were “turning Black poetry around” by writing with new energy about Black life and experience. She lauded their self-awareness, their fresh perspectives on long-standing issues, and the urgency and directness with which they wrote and performed. Brooks both supported and learned from these young artists: she joined them for readings in parks, housing projects, prisons, and taverns, thus connecting with previously unreached audiences. Many of the volumes shown here are from Brooks’s own library and include personal inscriptions to the poet by her mentees.

Don L. Lee (b. 1942; a.k.a. Haki R. Madhubuti)

Think Black

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1967

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198541

© Broadside Lotus Press

Nikki Giovanni (b. 1943)

Black Feeling, Black Talk, Black Judgement

New York: William Morrow, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198533

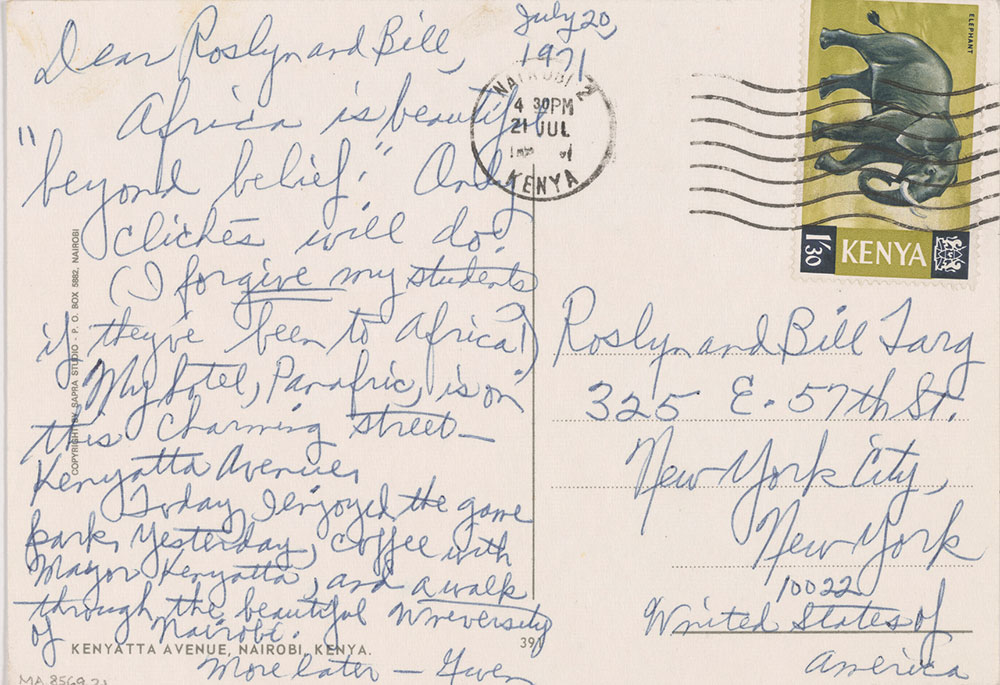

Autograph postcard

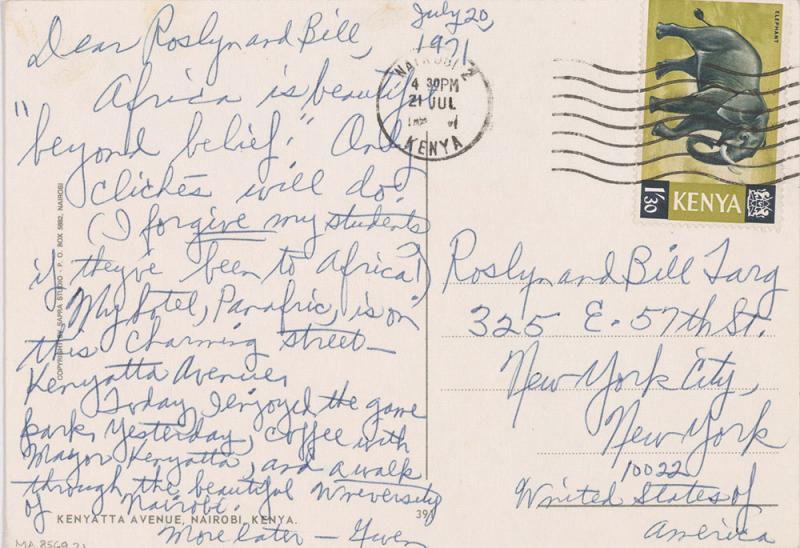

As Brooks became further engaged with the ideas of heritage and unity aligned with the Black Arts movement, it became increasingly important for her to travel to what she called “Mother Africa”—a trip she would take several times throughout her later life. On her first African journey in 1971, she visited Nairobi, where she was filled with both “warm joy and an inexpressible sadness” for the history that separated her from the land. In this postcard written to her friends and former editors Roslyn and Bill Targ, Brooks describes Kenya as “beautiful beyond belief.” Brooks found the experience so valuable that, after becoming a writing teacher, she periodically subsidized her students’ trips not only to Kenya but also Ghana and South Africa.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Autograph postcard, signed: Nairobi, to William and Roslyn Targ, 1971 July 20.

The Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; MA 8569.21

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

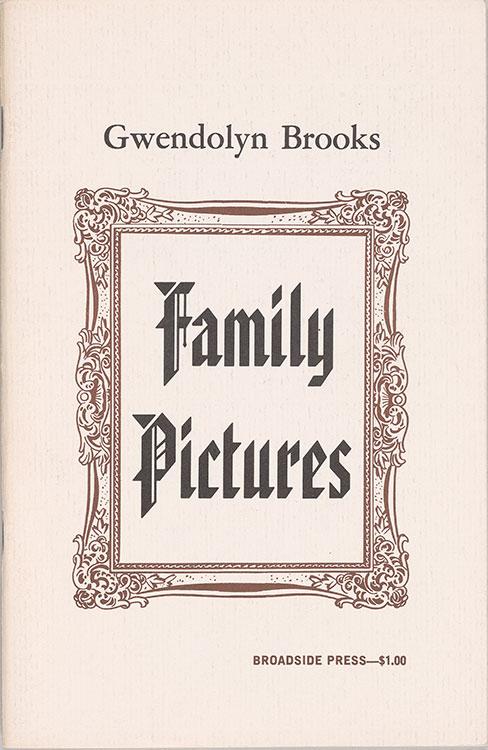

Family Pictures

Brooks kept a habit of writing poetry to and about her friends and fellow poets. The collection Family Pictures speaks to the importance of these relationships, containing poems about people Brooks considered “kin.” The central theme of the book is solidarity and unity in the face of global anti-Blackness, and the section “Young Heroes” contains dedication poems that show Brooks’s admiration and support of a new generation of Black writers in the United States and abroad. “Keorapetse Kgositsile,” for example, is titled after the South African Tswana poet, journalist, and political activist.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Family Pictures

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198515

© Broadside Lotus Press

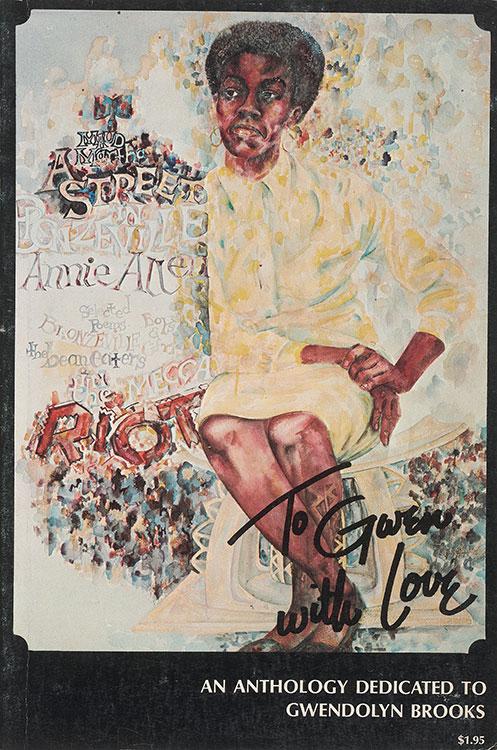

To Gwen with Love

Writer and educator Hoyt Fuller, in his introduction to the anthology To Gwen with Love, calls the volume a “gesture of affection and respect.” Its production was inspired by a 1969 tribute to Brooks that took place at the Affro-Arts Theater in Chicago, directed by actress Val Gray Ward, a friend of the poet’s. During the tribute, Black artists from around the country gathered to honor Brooks with performances, speeches, poetry, and music. This volume is a fitting testament to her influence, containing poems, fiction, essays, and illustrations from over sixty contributors. The cover design, created by artist Jeff Donaldson in his unique and colorful style, features Brooks surrounded by the titles of her published books.

To Gwen with Love

Edited by Patricia L. Brown, Haki R. Madhubuti (b. 1942; a.k.a. Don L. Lee), and Francis Ward (b. 1935)

Introduction by Hoyt Fuller (1923–1981)

Cover by Jeff Donaldson (1932–2004)

Chicago: Johnson Publishing, 1971

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021

The Estate of Jeff Donaldson, courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York.

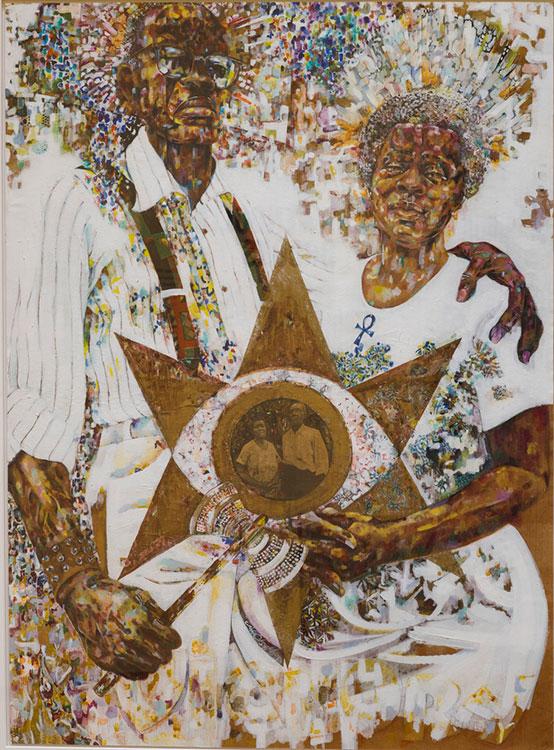

Victory In The Valley of Eshu

The Black Arts movement initiated a radical shift from the predominantly White mainstream art world, allowing Black artists to create their own institutions and metrics for what was considered art. The movement introduced a visual language that emphasized Black cultural history and celebrated Afrocentric imagery. Jeff Donaldson, cofounder of the artists’ collective AfriCOBRA and contributor to the mural the Wall of Respect in Chicago, used color and shape to represent Black subjects dynamically. His piece Victory in the Valley of Eshu speaks to the Black Art movement’s experimental nature.

Jeff Donaldson (1932–2004)

Victory in the Valley of Eshu, 1971

Watercolor, ink, gold paint, and cut-paper collage on cardboard

Courtesy Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York

A Teacher and Mentor

Brooks was highly invested in the education of younger generations, treating seriously the talents and issues of young people and teaching them how to use writing to navigate a difficult and discriminatory world. This focuses on Brooks’s impact as a teacher and mentor to younger writers throughout her career. Her dedication to youth education was obvious in her material and personal contributions to her students and mentees. Her commitment to the education of young people was multileveled and involved deep conversations about vulnerability and self-expression.

Brooks was highly invested in the education of younger generations, treating seriously the talents and issues of young people and teaching them how to use writing to navigate a difficult and discriminatory world. This focuses on Brooks’s impact as a teacher and mentor to younger writers throughout her career. Her dedication to youth education was obvious in her material and personal contributions to her students and mentees. Her commitment to the education of young people was multileveled and involved deep conversations about vulnerability and self-expression.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

To Disembark (Chicago: Third World Press, 1981)

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198569

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

To Disembark

Witnessing the ongoing violence affecting young people in her neighborhood—exemplified by this poem, “A Boy Died in My Alley”—Brooks started working with local youth. In 1970, alongside playwright Oscar Brown Jr. and poet-organizer Walter Bradford, her lifelong friend, Brooks began teaching creative writing to members of the Blackstone Rangers, a local gang composed mostly of teenagers and young adults. The Rangers had no interest in reading the classics or learning iambic pentameter, and they challenged Brooks to become more imaginative in her lessons. Brooks rose to the task and soon became not only a teacher but also a mentor and friend to the youths. She would go on to write poems in sympathy and solidarity with the young Rangers’ hopes and struggles.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

“A Boy Died in My Alley”

In To Disembark (Chicago: Third World Press, 1981)

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198569

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

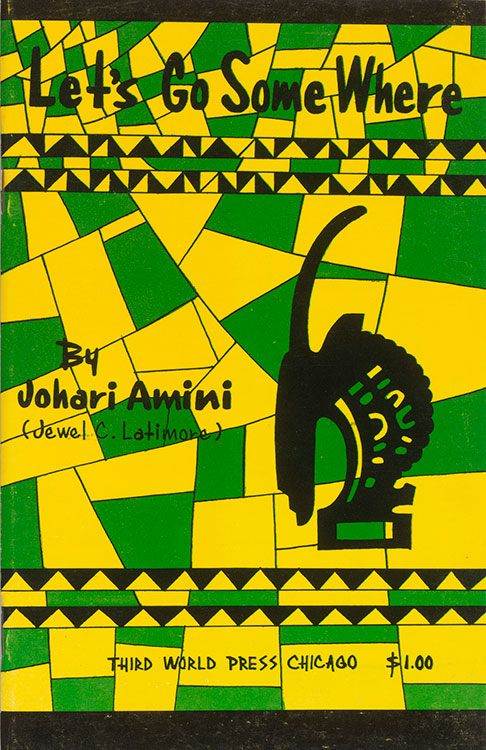

Let’s Go Some Where

Three members of Brooks’s writing workshop—Johari Amini, Don L. Lee (a.k.a. Haki R. Madhubuti), and Carolyn Rogers—established their own publishing company, Third World Press, in December 1967. The press began in Madhubuti’s basement apartment on the South Side of Chicago with four hundred dollars, a used mimeograph machine, and a commitment to publishing texts by writers involved in the Black Arts movement. It has since grown to become one of the most formidable Black publishing houses in the United States. Brooks would release five books, including her second memoir, Report from Part Two (1996), with Third World Press, working closely with her former mentees.

Johari Amini (b. 1935)

Let’s Go Some Where

Introduction by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Chicago: Third World Press, 1973

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198722

Reproduced with the permission of Omar Lama

Don L. Lee (b. 1942; a.k.a. Haki R. Madhubuti)

Don’t Cry, Scream

Introduction by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198581

© Broadside Lotus Press

The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves, or, What You Are You Are

Brooks published a number of children’s books throughout her career, often using the medium to discuss topics such as acceptance and belonging. The mother of two children, Henry (born 1940) and Nora (born 1951), Brooks was frequently inspired by her experience as a parent to write about the trials and tribulations of childhood. Her books for young readers were extensions of the lessons that she shared with her son and daughter, bringing what she called the “privacy of family pleasure” to the world.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

The Tiger Who Wore White Gloves, or, What You Are You Are

Chicago: Third World Press, 1974

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198523

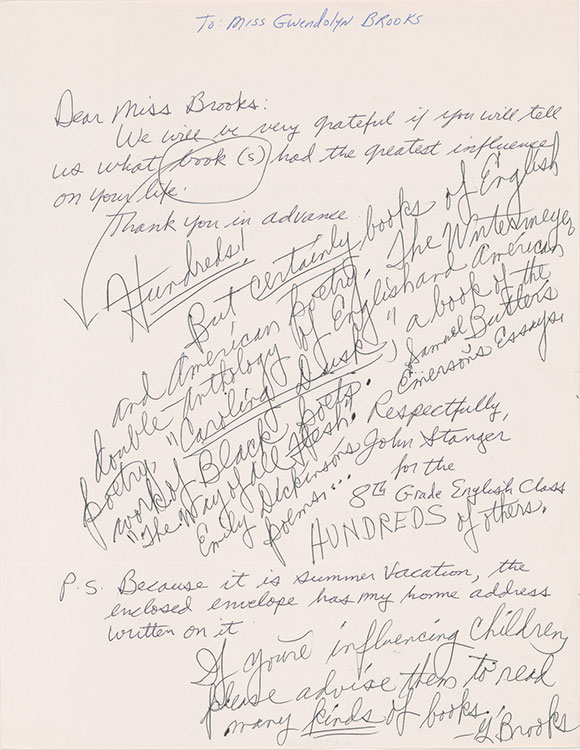

Letter to Gwendolyn Brooks

As a teacher, Brooks went above and beyond for her students, making sure they were exposed to many types of literature and purchasing them tickets to local poetry readings. As Brooks wrote in this letter to an eighth-grade teacher, “If you’re influencing children, you must encourage them to read many kinds of books.” Throughout her career, Brooks continued to support younger writers both financially and educationally.

John Stanger

Letter to Gwendolyn Brooks with Brooks’s response, 1990–92

Purchased on the Drue Heinz Fund for Twentieth-Century Literature, 2020; MA 23730.4

Reprinted By Consent of Brooks Permissions

Young Poet’s Primer

Inspired by her years of teaching and experience working with independent Black publishers, Brooks created her own imprint in 1980 and produced these guides for young poets. Brooks thought it was essential that young people have the opportunity to express themselves. “A teacher cannot create a poet,” she once said, but “a teacher can oblige the writing student to write.” The covers of these books, like the writing exercises in them, are simple and inviting, aiming to introduce a new generation to the joy of poetry.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Young Poet’s Primer

Chicago: Brooks Press, 1981

Very Young Poets

Chicago: Brooks Press, 1983

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2020; PML 198652, PML 198653

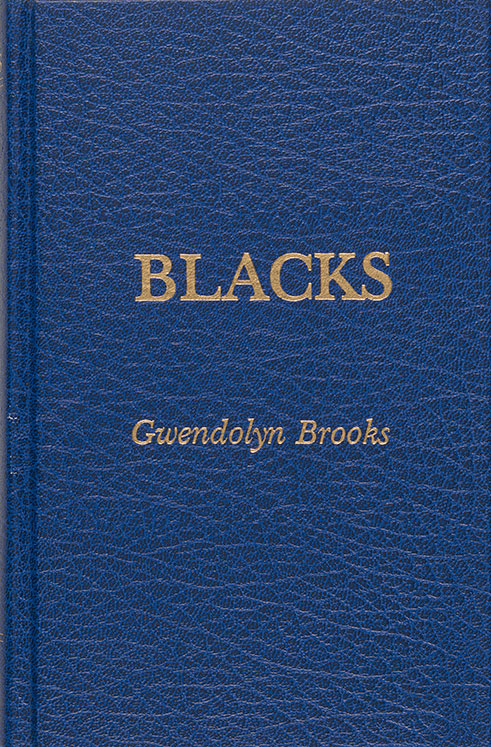

Blacks

Blacks, the largest collection of Brooks’s work, was designed by the poet—an advantage of self-publishing that she valued greatly. The deep-blue binding and gilt cover evoke a Bible or dictionary, at once aesthetically pleasing and meant for everyday use and consultation. The dust jacket’s simple design is a trademark of Brooks’s self-published volumes. The David Company, her second imprint, was named in honor of her father, David Anderson Brooks. Gwendolyn credited his habit of singing and reciting poetry throughout the house with inspiring her to write poems in her youth. These tender moments are present in her poetry as an inspiration for all who read.

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000)

Blacks

Chicago: David Company, 1987

Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198691

Poems

southeast corner

The School of Beauty’s a tavern now.

The Madam is underground.

Out at Lincoln, among the graves

Her own is early found.

Where the thickest, tallest monument

Cuts grandly into the air

The Madam lies, contentedly.

Her fortune, too, lies there,

Converted into cool hard steel

And bright red velvet lining;

While over her tan impassivity

Shot silk is shining.

From A Street in Bronzeville (1945)

Chicago's South Side, 1970. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

a song in the front yard

I’ve stayed in the front yard all my life.

I want a peek at the back

Where it’s rough and untended and hungry weed grows.

A girl gets sick of a rose.

I want to go in the back yard now

And maybe down the alley,

To where the charity children play.

I want a good time today.

They do some wonderful things.

They have some wonderful fun.

My mother sneers, but I say it’s fine

How they don’t have to go in at quarter to nine.

My mother, she tells me that Johnnie Mae

Will grow up to be a bad woman.

That George’ll be taken to Jail soon or late

(On account of last winter he sold our back gate).

But I say it’s fine. Honest, I do.

And I’d like to be a bad woman, too,

And wear the brave stockings of night-black lace

And strut down the streets with paint on my face.

From A Street in Bronzeville (1945)

Children play outside of their homes in Bronzeville, 1967. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

of De Witt Williams on his way to Lincoln Cemetery

He was born in Alabama.

He was bred in Illinois.

He was nothing but a

Plain black boy.

Swing low swing low sweet sweet chariot.

Nothing but a plain black boy.

Drive him past the Pool Hall.

Drive him past the Show.

Blind within his casket,

But maybe he will know.

Down through Forty-seventh Street:

Underneath the L,

And Northwest Corner, Prairie,

That he loved so well.

Don’t forget the Dance Halls—

Warwick and Savoy,

Where he picked his women, where

He drank his liquid joy.

Born in Alabama.

Bred in Illinois.

He was nothing but a

Plain black boy.

Swing low swing low sweet sweet chariot.

Nothing but a plain black boy.

From A Street in Bronzeville (1945)

A Chicago L train rounds the track, 1968. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell

I hold my honey and I store my bread

In little jars and cabinets of my will.

I label clearly, and each latch and lid

I bid, Be firm till I return from hell.

I am very hungry. I am incomplete.

And none can tell when I may dine again.

No man can give me any word but Wait,

The puny light. I keep eyes pointed in;

Hoping that, when the devil days of my hurt

Drag out to their last dregs and I resume

On such legs as are left me, in such heart

As I can manage, remember to go home,

My taste will not have turned insensitive

To honey and bread old purity could love.

From A Street in Bronzeville (1945)

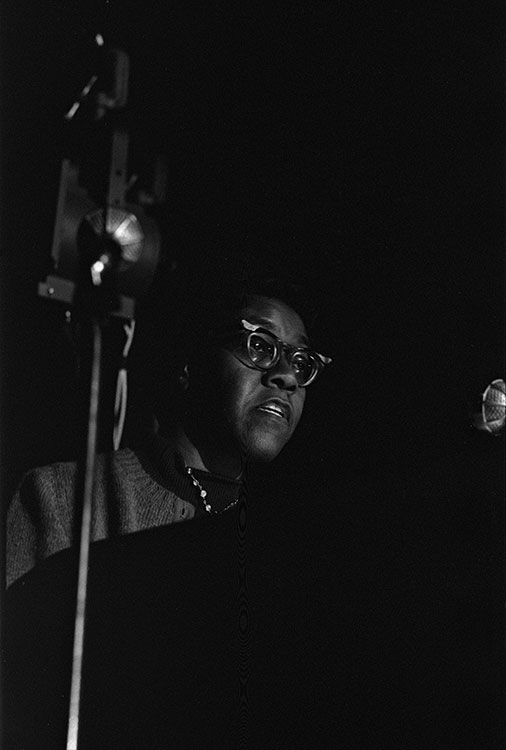

Brooks speaks at Affro-Arts Theater, 1968. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

The birth in a narrow room

Weeps out of western country something new.

Blurred and stupendous. Wanted and unplanned.

Winks. Twines, and weakly winks

Upon the milk-glass fruit bowl, iron pot

The bashful china child tipping forever

Yellow apron and spilling pretty cherries.

Now, weeks and years will go before she thinks

"How pinchy is my room! How can I breathe!

I am not anything and I have got

Not anything, or anything to do!"-

But prances nevertheless with gods and fairies

Blithely about the pump and then beneath

The elms and grapevines, then in darling endeavor

By privy foyer, where the screenings stand

And where the bugs buzz by in private cars

Across old peach cans and jelly jars.

From Annie Allen (1949)

Young people gathered on fire escapes on Chicago's South Side, 1970. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

truth

And if sun comes

How shall we greet him?

Shall we not dread him,

Shall we not fear him

After so lengthy a

Session with shade?

Though we have wept for him,

Though we have prayed

All through the night-years—

What if we wake one shimmering morning to

Hear the fierce hammering

Of his firm knuckles

Hard on the door?

Shall we not shudder?—

Shall we not flee

Into the shelter, the dear thick shelter

Of the familiar

Propitious haze?

Sweet is it, sweet is it

To sleep in the coolness

Of snug unawareness.

The dark hangs heavily

Over the eyes.

From Annie Allen (1949)

Residential street in Chicago. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

The Last Quatrain of the Ballad of Emmett Till

(After the murder, After the burial)

Emmett's mother is a pretty-faced thing;

the tint of pulled taffy.

She sits in a red room,

drinking black coffee.

She kisses her killed boy.

And she is sorry.

Chaos in windy grays

through a red prairie.

From The Bean Eaters (1960)

Woman stands in front of Unity Hall, a historic building for black political organizing in Chicago, 1967. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

The Artists' and Models' Ball (For Frank Shepherd)

Wonders do not confuse. We call them that

And close the matter there. But common things

Surprise us. They accept the names we give

With calm, and keep them. Easy-breathing then

We brave our next small business. Well, behind

Our backs they alter. How were we to know.

From The Bean Eaters (1960)

Gallery viewing at the South Side Community Art Center, 1967. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.

Speech to the Young, Speech to the Progress-Toward (Among them Nora and Henry III)

Say to them,

say to the down-keepers,

the sun-slappers,

the self-soilers,

the harmony-hushers,

"Even if you are not ready for day

it cannot always be night."

You will be right.

For that is the hard home-run.

Live not for battles won.

Live not for the-end-of-the-song.

Live in the along.

From Family Pictures (1970)

Young people gathered near the Wall of Respect in Chicago, 1967. Photography by Robert Sengstacke, courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive at The University of Chicago Visual Resources Center.