Imperial Splendor: The Art of the Book in the Holy Roman Empire, ca. 800–1500

Encompassing parts of modern-day Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and northern Italy, the Holy Roman Empire represented a patchwork of various kingdoms, often united more through uneasy alliances than actual power. In contrast to the centralized monarchies of France and England, it lacked a single, constant national capital, which impeded the emergence of bureaucratic institutions and the ability to regulate a range of customs and practices, from religion and education to book production. Just as the empire embraced many languages and ethnic groups, it also included a mix of sometimes conflicting cultural traditions. The various challenges that were particular to the empire contributed to some of its defining characteristics: the ever-shifting balance of power between court, church, and cloister; the integration of aristocratic and monastic patronage; and the rise of cities as independent centers of commerce and education. Decentralization went hand in hand with artistic and cultural diversity.

Taking as its subject the role of manuscript illumination in the Holy Roman Empire throughout the Middle Ages, Imperial Splendor offers a sweeping overview of one of the most impressive chapters in the history of medieval art. Beginning with the reforms initiated by Charlemagne (ca. 748–814), the first emperor in Europe after the fall of Rome, and ending with the flurry of artistic innovation coinciding with the invention of the printing press and the onset of humanism in the fifteenth century, this exhibition examines the intersections of art, books, and power.

Imperial Splendor: The Art of the Book in the Holy Roman Empire, 800–1500 is made possible by the Janine Luke and Melvin R. Seiden Fund for Exhibitions and Publications, the Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund, the Christian Humann Foundation, and Katharine J. Rayner. Additional support is provided by the David L. Klein Jr. Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Research and Publications; Caroline Sharfman Bacon; Elizabeth A. R. and Ralph S. Brown, Jr.; Mr. and Mrs. Alain Goldrach; Marguerite Steed Hoffman and Tom Lentz; Professor James H. Marrow and Dr. Emily Rose; Mrs. Andrew C. Schirrmeister; the Samuel H. Kress Foundation; Gifford Combs; Salle Vaughn; William M. Voelkle; Gregory T. Clark; Bob McCarthy; and an anonymous donor.

“Heiningen Gospels” (fragment), in Latin, Germany, Hamersleben, ca. 1180–1200. Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.565, fols. 13v–14r. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905.

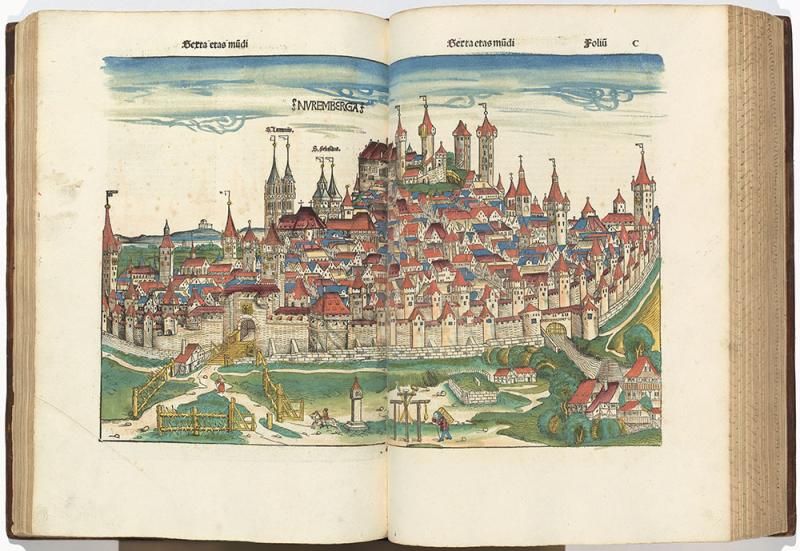

The Structure of the Empire

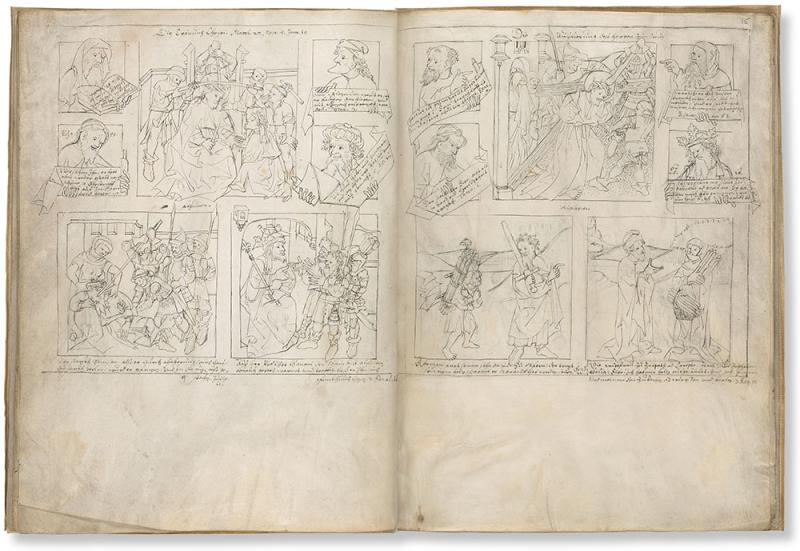

The history of the Holy Roman Empire challenges notions that nationhood and nationality are predetermined by shared ethnicity and language. The territories gathered within its borders constituted a diverse, multiethnic, and highly decentralized confederation of states and jurisdictions, loosely allied under an elective, rather than hereditary, monarchy. Although historically associated with Germany, the empire in the Middle Ages spread well beyond German-speaking lands. Its multilingual character was acknowledged in the Golden Bull of 1356, the equivalent of its constitution, which encouraged electors and their successors to learn German, Latin, Italian, and Czech as official languages. By the late Middle Ages, the imperial Diet, or deliberative assembly—later known as the Reichstag—provided the means through which the empire’s many territories and free cities came to convene and negotiate among themselves. The structure of the Reichstag is reflected in a grand two-page spread from the “Nuremberg Chronicle,” a popular universal chronicle covering the history of the world from Creation to the Last Judgment. The three colleges (collegia), or governing bodies of the empire, are represented in a schematic fashion. At top are the seven prince-electors, followed by various ranks of nobility as well as representatives from the free imperial cities. By the eve of the Reformation there were as many as fifty-three principalities within the empire, lending it its familiar patchwork character.

HIERARCHY OF THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE, CA. 1500

Collecting Medieval Manuscripts

The collecting of medieval art in America coincided with a particularly active moment in the history of the European art market. Although there was little interest in medieval art among American collectors for most of the nineteenth century, the years around 1900 witnessed the emergence of a new generation of wealthy amateurs like J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) and Henry Walters (1848–1931). For the most part, these collectors were not devoted to any single period of art but rather collected widely across many different fields. Working closely primarily with European dealers, they acquired vast amounts of art and rare books at a time when aristocratic collections in Europe were increasingly being sold to raise funds. Medieval manuscripts had made their way into those aristocratic collections much earlier in the century, when a process of secularization resulted in their transfer from religious institutions into either national collections or private hands. More than any other collection in North America, J. Pierpont Morgan’s library came to include treasures of early medieval art, among them manuscripts associated directly or indirectly with imperial patronage—hence the title Imperial Splendor. Such patronage provides the leitmotif of the exhibition, beginning with the four manuscripts displayed below. They date to the ninth century, a period named “Carolingian” after Charlemagne (ca. 748–814) and his heirs, the first medieval emperors in western Europe.

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1914 or later. The Morgan Library & Museum, ARC 1628. Photography by Tebbs and Knell.

Overview

Gallery Images

Imperial Networks

9th–11th Century

The Carolingian and Ottonian dynasties, named after Charlemagne (ca. 748–814) and Otto I (912–973), respectively, laid the groundwork for the Holy Roman Empire. Their rulers deliberately sought out the imperial title to legitimize their control over diverse kingdoms and principalities that, at the empire’s height, encompassed much of present-day western and central Europe. The manuscripts produced during their rule engaged with the legacy of ancient Rome and embodied the ambitions of the patrons for whom they were made. Scribes and artists in this period developed prestigious visual and graphic elements for their books, including the use of gold ink, purple parchment, a hierarchy of scripts, elaborate decorative initials, and spectacular treasure bindings. Paying attention as much to visual qualities as to content, the Carolingians and Ottonians fundamentally shaped the role of illuminated manuscripts in the Middle Ages. The most deluxe works were often commissioned as gifts and thus played a crucial role across carefully cultivated networks of power. These manuscripts featured prominently in solemn rituals at the heart of both religious life and governance. As preservers of institutional memory, the illuminated manuscripts of this period vividly articulate notions of empire, authority, and tradition.

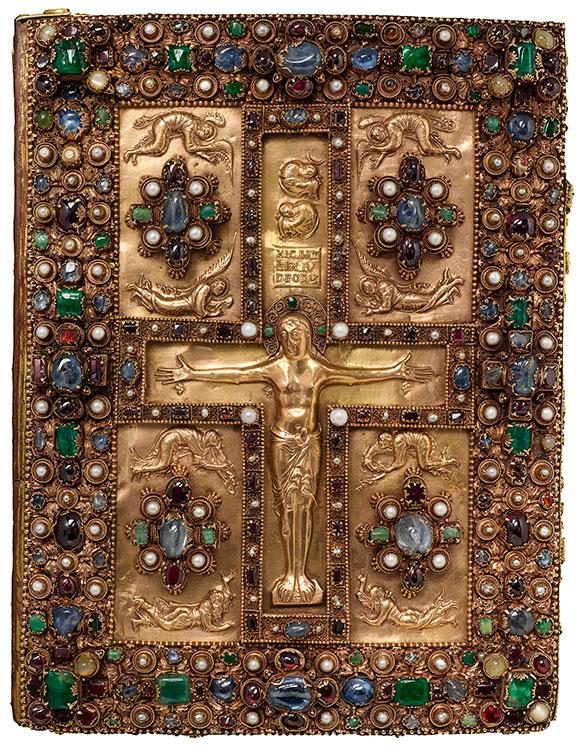

Lindau Gospels

BOOK AS TREASURE

This treasure binding is a composite made of two distinct covers brought together on a Gospel book written and illuminated toward the end of the tenure of Hartmut, abbot of St. Gall, likely for ceremonial use in the abbey church. The jeweled front cover must have been a royal gift of immense importance. It is one of only three surviving examples of metalwork that can be attributed to the court workshop of Emperor Charles the Bald (823–877), who, like his grandfather Charlemagne, was a great patron of illuminated manuscripts. The back cover may have once belonged to a Gospel book commissioned by Charlemagne’s rival Tassilo III (ca. 741–796), Duke of Bavaria. Also, the rare Byzantine and Syrian silks lining the inside covers were likely gifts. Because Carolingians lacked the technology to produce silk, such textiles were highly coveted luxury items, often distributed through royal networks.

"Lindau Gospels," in Latin

Switzerland, St. Gall, ca. 880 (manuscript)

Eastern France, ca. 870 (front cover)

Austria, Salzburg region, ca. 780–800 (back cover)

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1901

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This magnificent gospel book was written and illuminated in the late ninth century, at the monastery of St. Gall, which is strategically located along one of the alpine passes leading to Italy. The spectacular front and back covers of the manuscript were made elsewhere and predate the book itself.

The golden front cover is a masterpiece of Carolingian metalwork. The figure of Christ on the cross dominates the center of the composition, around which ten figures are arranged in dramatic poses of grief. Directly above Christ, personifications of the sun and moon mourn his death, as do the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist beneath the cross.

The back cover is no less remarkable. Created for a now-lost luxury gospel book, the cover was made in or around Salzburg about a hundred years earlier than the manuscript it now adorns. Its design consists of a large cross with flared arms, set inside a rectangular enamel frame. Certain details lend the cover a cosmological dimension. The Greek letters alpha and omega are inscribed on the vertical arm of the cross and refer to the beginning and end of time. Likewise, the mass of snakes and other creatures filling the four carved plaques between the arms of the cross establish a link between the Gospels and the primordial act of creation.

Both covers likely reached St. Gall as royal gifts of immense importance. A similar route can be surmised for the rare silk textiles lining the inside of both covers. Because the Carolingians lacked the technology to produce silk for themselves, such textiles were highly coveted luxury items, and were often distributed through royal networks.

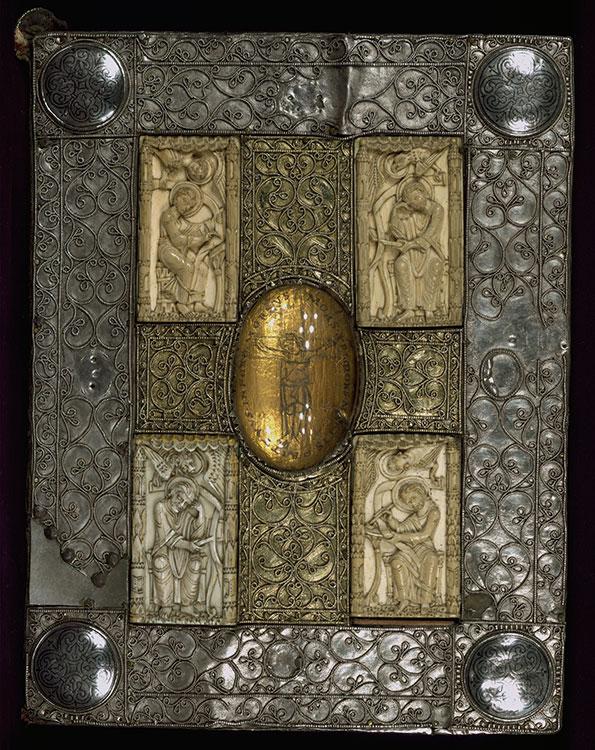

Gospel Lectionary

BOOK AS TREASURE

This treasure binding, original to its manuscript, consists of a silver-filigree frame, a silver-gilt cross (noticeably more golden in color), and four ivory plaques of the evangelists (Mark, lower left, is a modern replacement). At its center, the cross features a polished rock crystal protecting an image of the Crucifixion drawn on gold foil. A splinter of the True Cross rests upon Christ’s chest. The surrounding inscription, “The death of Christ was the death of death, and your bite, O Hell,” emphasizes the paradox of Christ’s death as a triumph of eternal life. Through this deliberate staging, the relic appears as the source of the cross’s life-giving power, which emanates from the center in the form of the cover’s abundant vegetal motifs. The book was created at Regensburg, likely for the Benedictine abbey of Mondsee (near Salzburg), where it was preserved for much of the Middle Ages.

Gospel Lectionary, in Latin

Germany, Regensburg, ca. 1030–50, with later additions

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.8

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

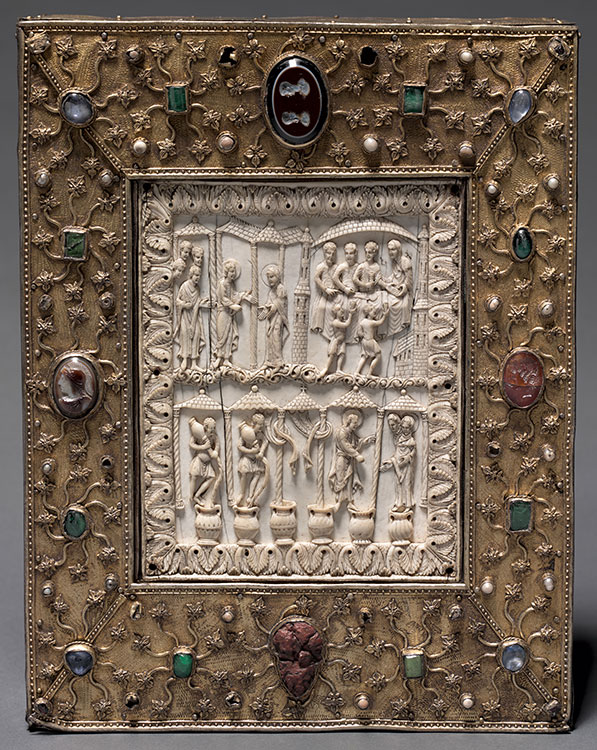

Book-Shaped Reliquary

BOOK AS TREASURE

Modeled after a treasure binding, this reliquary was commissioned by Duke Otto the Mild (1292–1344) as part of his magnificent memorial donation to the collegiate church (now cathedral) of St. Blaise in Brunswick. The engraved effigies of that church’s three patron saints on the reverse tie the object to the dynastic foundation. The front cover reuses much older objects, including an eleventh-century ivory of Christ’s miracle at the Wedding at Cana, as well as ancient cameos—small carved glass or gemstone plaques—interspersed with precious gems. The use of such spolia (spoils) forms part of a broader representational program that proclaimed the status and authority of the patron’s family while adding to the prestige of their local church. Among the relics within were pages from the four Gospels, lending the object a quasi-liturgical function.

Book-Shaped Reliquary

Germany, Lower Saxony, ca. 1340 (reliquary)

Belgium, Liège (?), late eleventh century (ivory)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Gift of the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust, 1930.741

Saint-Remi Gospels

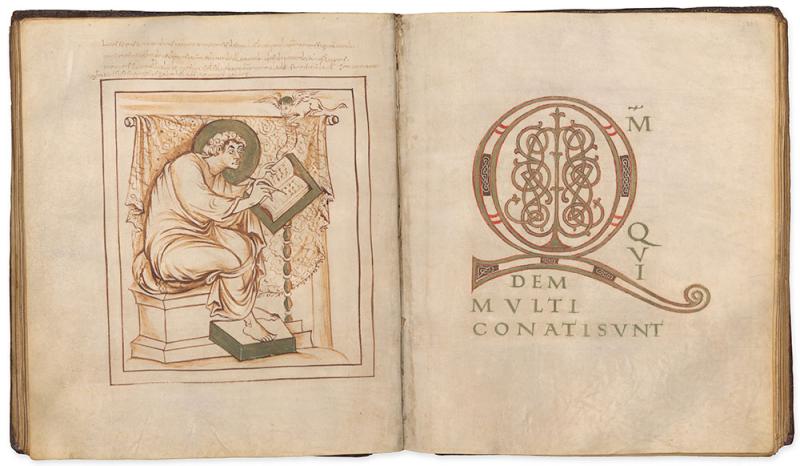

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Among the largest cities in Roman Gaul, Reims was also a center of artistic renewal in the Carolingian empire. This efflorescence was fostered by enterprising archbishops like Hincmar of Reims (806–882), who renovated several important monasteries in his domain, including Saint-Remi just outside the city walls. Preserving the relics of St. Remigius, who baptized King Clovis and converted the Franks to Christianity, the monastery laid claim to a fundamental moment in Frankish history. Commissioned by Hincmar for Saint-Remi’s rededication, this manuscript was written exclusively in gold ink. The portrait of the evangelist Matthew is deeply classicizing, a reference to the city’s ancient past. Featuring the opening words of the Gospel, the purple ground of the facing page likewise refers to imperial traditions.

"Saint-Remi Gospels," in Latin

France, Reims, ca. 852

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.728, fols. 14v–15r

Purchased, 1927

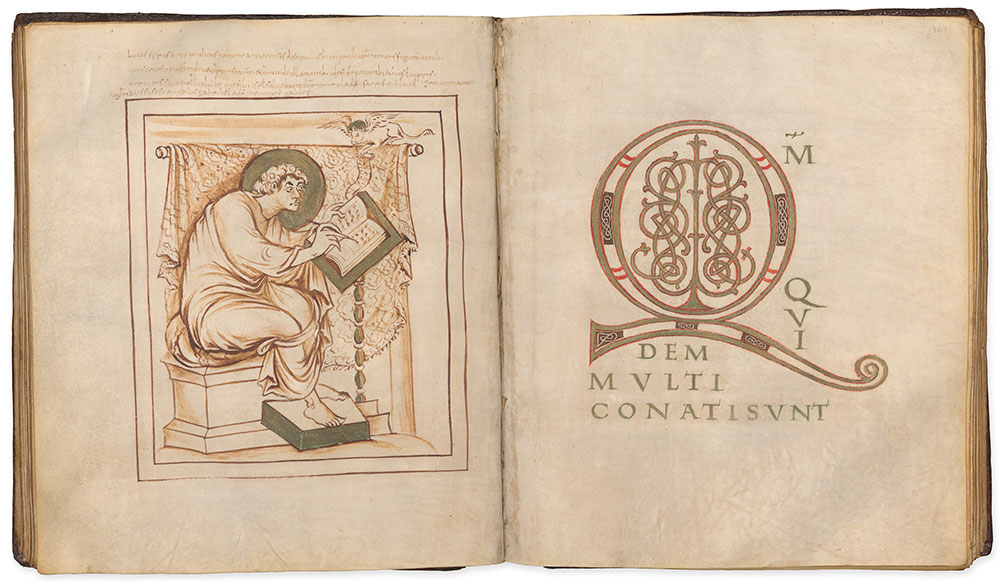

Gospel Book (MS M.640)

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Books played a crucial role in establishing networks of power. Over twenty Carolingian manuscripts name Hincmar of Reims as donor, and many more are associated with his patronage. Most were created for use in and around Reims, but their influence was widespread. This Gospel book features two evangelist portraits and the beginnings of a third, all drawn in a distinctly Reimsian style. While to a certain extent unfinished, the heavy use of shading—as evident in this image of the evangelist Luke—suggests that the portraits were never intended to be painted. The artist may have been trained at Reims, but the manuscript itself was produced at an unknown regional scriptorium. The use of brass instead of gold further suggests that the manuscript was not produced at a major center.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Northeastern France or Belgium (Liège?), late ninth century

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.640, fols. 100v–101r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1919

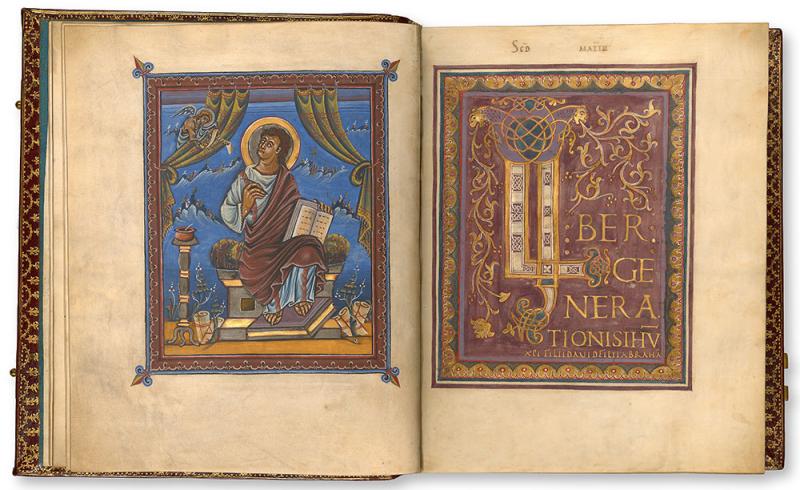

Gospel Book (MS M.860)

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Inviting to his court the best scholars throughout Europe, Emperor Charlemagne (ca. 748–814) attempted to reform and standardize writing itself, which varied widely across the empire. Scribes working at important monastic centers like St. Martin at Tours developed new styles of script modeled on those of the ancient Romans. In this manuscript from Tours, the title page (at left) announces the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel. Written on bands of imperial purple, the golden capitals recall stone-carved inscriptions of ancient Rome. At right, Matthew’s Gospel begins with Liber generationis (Book of the generation of Jesus Christ). Here, the scribe combines Roman letterforms with nonclassical interlace ornaments, transforming sacred words into a work of art.

Gospel Book, in Latin

France, Tours, ca. 857–62

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.860, fols. 14v–15r

Purchased with the Assistance of the Fellows, 1952

Epistle Lectionary

CAROLINGIAN PRECEDENTS

Strategically located along one of the alpine passes leading to Italy, the abbey of St. Gall was favored by Carolingian rulers, who demonstrated their support through a series of privileges, allowing the monks to govern themselves independently from the local bishop. Abbot Hartmut (r. 872–83) actively fostered its cultural life, commissioning a great number of books to be written “for the communal use of the monastery.” Among them was this lectionary, illuminated in a characteristic nonfigural style. The alternating gold and silver of the manuscript’s opening initials echoes the alternating gold and silver lines of text. While these opening pages are the most prominently decorated, the manuscript contains nearly 150 decorative initials, each of which introduces a reading for Sundays and special feast days.

Epistle Lectionary, in Latin

Switzerland, St. Gall, ca. 880

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.91, fols. 1v–2r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905

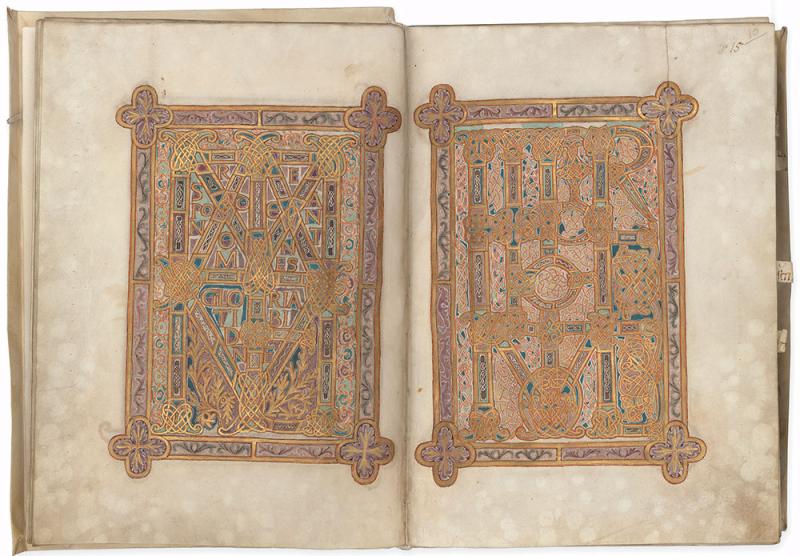

Astor Lectionary

OTTONIAN BEGINNINGS

Looking back to Carolingian models (on view at the entrance to the exhibition), illuminators at Corvey developed a new style of painting that was largely abstract, using ornamental forms inspired by silks, gems, enamels, sumptuous metalwork, and imperial monograms. These manuscripts demonstrated not only the wealth and munificence of the imperial family but also the international status of their power. This Gospel lectionary features ornamental pages that preface the readings for important Masses. For Christmas, thirteen words stretch across nine pages of designs culminating in the word Mattheum (Matthew), at left, depicted in a monogrammatic composition. At right, the same approach is used to form the words In illo tempore (In that time). As the personal signs of rulers, monograms were potent symbols of authority in the Middle Ages and possessed a nearly magical quality.

"Astor Lectionary," in Latin

Germany, Corvey, ca. 950

New York Public Library, MA 1, pp. 14–15

Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

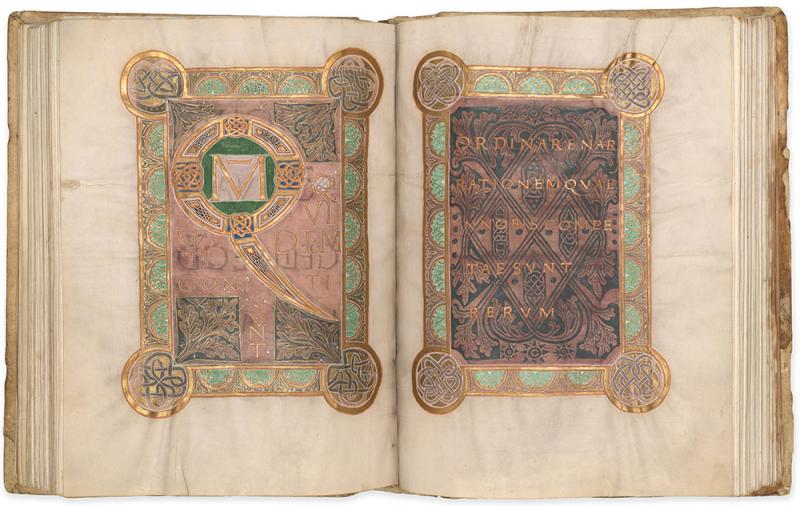

Quedlinburg Gospels

OTTONIAN BEGINNINGS

This Gospel book was likely made for the imperial convent of Quedlinburg, among the most important foundations in Saxony. Established in 936 by Otto I and his mother, Mathilda, the abbey served as a memorial site for the Ottonian family. Its abbesses were Ottonian princesses, many of whom were actively engaged in politics. Befitting such prestige, this manuscript is one of the largest and most splendidly illuminated products of the Corvey scriptorium. Luke’s Gospel begins with an elaborate interlace initial Q framed by monochrome textile designs in the corners. The text continues in gold on the facing page, set against a striking textile background in shades of purple. The evocation of luxury objects like silk cloth relates to Otto’s extensive diplomatic activities, which resulted in the exchange of precious goods from centers spanning from Córdoba to Constantinople.

"Quedlinburg Gospels," in Latin

Germany, Corvey, ca. 950–70

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.755, fols. 99v–100r

Purchased, 1929

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Beginning around the middle of the tenth century, Otto the Great, or members of his family, began commissioning a number of deluxe manuscripts from the scriptorium at Corvey—an important monastery in Saxony. Little is known about the exact circumstances of their production, but both the script and illumination of these manuscripts suggest close ties with the imperial family. Based on their early histories of ownership, these manuscripts were likely produced for export as imperial gifts.

This gospel book is among the largest and most splendidly illuminated products of Corvey in the tenth century. It was likely made for the convent of Quedlinburg, which served as a mausoleum for the imperial family. Each of the four gospels in this book begins with a sumptuous four-part sequence of ornamental text pages. Shown here is the opening for the Gospel of Luke, the first word of which (quoniam) is formed by an elaborate initial Q framed by monochromatic textile designs in the four corners. The sacred text continues in gold on the facing page, which likewise features a striking textile design for the background. These pages exemplify the new style of painting developed by illuminators at Corvey—a style that was largely abstract and inspired by precious luxury objects like silk textiles, gems, enamels, and metalwork.

Ornate in the extreme, these manuscripts were meant to do more than just dazzle their viewers. The particular approach to painting developed at Corvey demonstrated not only the wealth and munificence of the imperial family, but also the international status of their power.

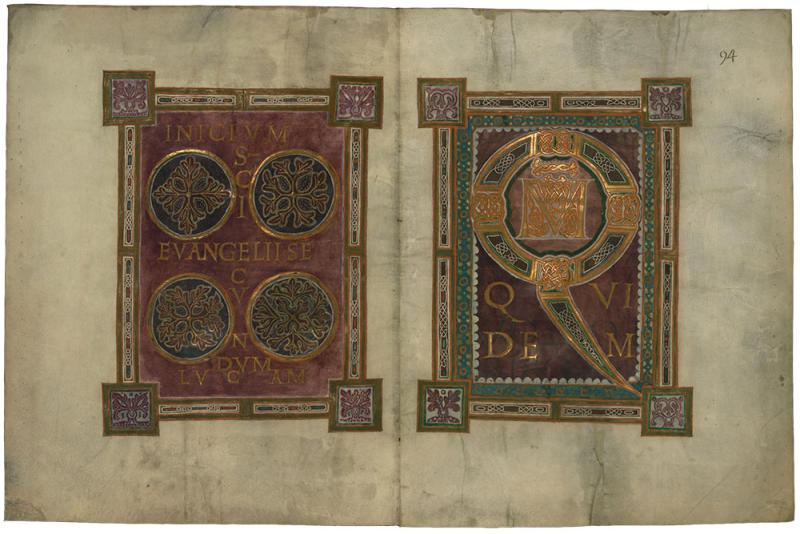

Gospel Book (Fragment)

OTTONIAN BEGINNINGS

These fragmentary leaves once formed part of a Gospel book given to Reims Cathedral. Otto I’s younger brother Bruno (925–965) was not only duke of Lotharingia and archbishop of Cologne, but also regent of France during this period. He had a particularly strong interest in Reims and perhaps played a role in the donation of this manuscript. The title page for Luke’s Gospel, at left, demonstrates how painters could simulate precious materials. Four fictive enamel medallions occupy most of the page. Filling the spaces between the medallions, the golden text takes on the form of a cross. The facing page features a large initial Q framed by a fictive enamel border, seemingly lined with pearls. The unusually painted vegetal motifs in the corners of each page evoke carved gems (intaglios).

Gospel Book (Fragment), in Latin

Germany, Corvey, ca. 950–70

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.751, fols. 1v–2r

Purchased, 1952

Gospel Book (MS M.651)

OTTONIAN PATRONAGE

Marking a break from local painting traditions in Cologne, this Gospel book demonstrates the influence of artistic developments at the island monastery of Reichenau, an important center of Ottonian patronage. The portrait of Matthew features an expansive gold background, faintly articulated with golden vegetal motifs at bottom and nearly imperceptible golden stars above. Matthew’s symbol, a winged man, emerges from the architecture to offer him a scroll. The facing page combines Reichenau traits—the curved L, for example, and the anchoring of the initial to the frame—with elements more local to Cologne, such as the portrait medallions, inspired by ancient coinage. Although the patron of this manuscript is unknown, its illumination points to the high standing of Cologne, whose bishops were often active as chancellors at court.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Cologne, ca. 1030

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.651, fols. 8v–9r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1920

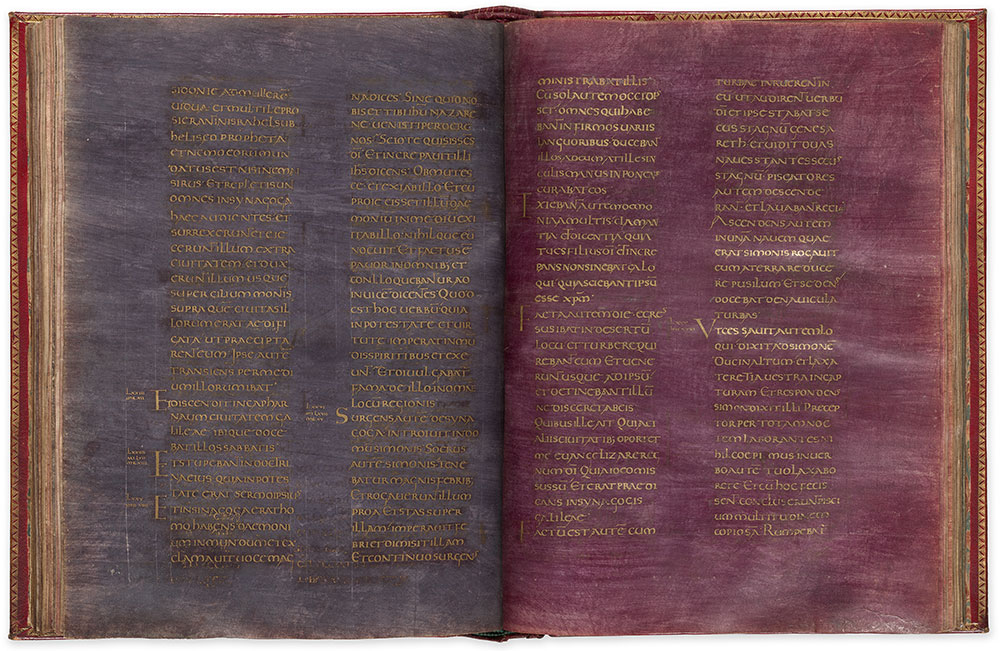

Golden Gospels

OTTONIAN PATRONAGE

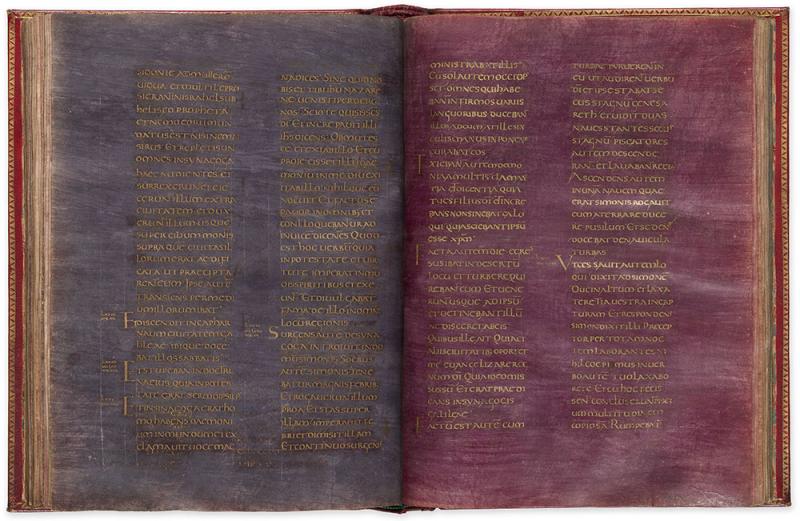

This Gospel book was written entirely in gold ink on purple-painted parchment. It evokes the venerable tradition of ancient manuscripts represented by the fragmentary leaf from a sixth-century Gospel book displayed above.

The “Golden Gospels” contains only the sacred text, written in double columns using an uncial (uppercase) script long out of fashion by the tenth century. With as many as sixteen scribes copying the text, the finished leaves were stacked together before the gold ink was completely dry, leaving visible offsets. The plant-based purple pigment varies in hue to such an extent that several batches must have been made, without regard for consistency. The manuscript was likely created in haste, perhaps as an imperial gift to mark a particular occasion for which there was little time to prepare. The intended recipient is unknown, but in the sixteenth century it was owned by King Henry VIII of England.

"Golden Gospels," in Latin

Germany, Trier, ca. 980

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.23, fols. 72v–73r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1900

Leaf from a Gospel Book (“Codex Petropolitanus”), in Greek

Syria, Antioch (?), sixth century

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.874

Purchased, 1955

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This grandiose gospel book is the last in a long line of deluxe manuscripts written entirely in gold or silver ink on parchment that has been stained purple, a color traditionally reserved for emperors and their family. This ancient tradition dates back to the time of the earliest Christian emperors like Constantine the Great, who ruled in the early fourth century. However, by the time this manuscript was made, in the late tenth century, the tradition of the purple codex had largely come to an end. The patron of this manuscript, who may have been Archbishop Egbert of Trier, a former chancellor of Emperor Otto II, likely intended to recreate the appearance of an ancient purple manuscript.

This gospel book was almost certainly made as a gift, and its production involved an enormous team of skilled artisans, including as many as sixteen scribes. They worked in great haste, often stacking together the freshly written pages before the gold ink was completely dry, which explains the offsets visible at the bottom of the left page. The fact that this book was later owned by King Henry VIII of England suggests that it may have been created as a gift from the Ottonian emperors to an English dignitary.

A brief painted inscription runs along the outer fore-edge of the manuscript, stating that “the inside of the book is more ornate than the outside.” This inscription refers in a typically medieval way to a now-lost treasure binding that once adorned the manuscript. The inscription juxtaposes the conspicuous material value of the now-lost jeweled covers with the much greater spiritual value of the book’s text.

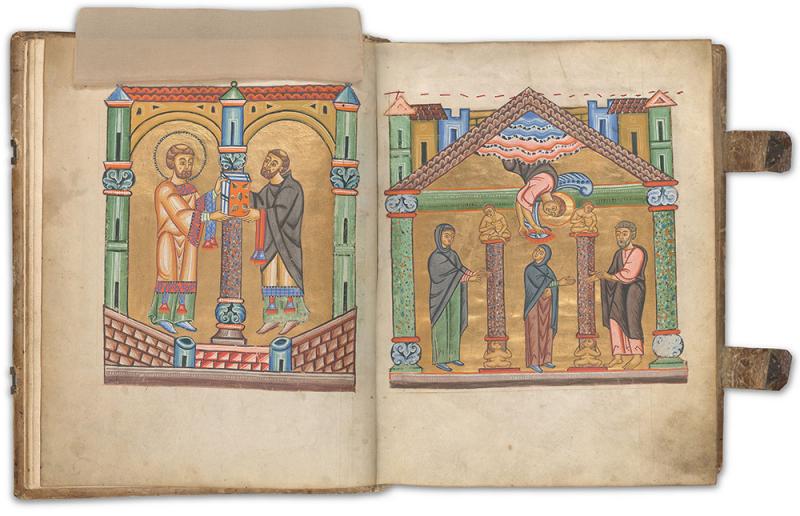

Gospel Book (MS W.7)

OTTONIAN PATRONAGE

The island monastery of Reichenau was among the most celebrated centers of artistic production during the Ottonian period. Nearly sixty deluxe manuscripts from its scriptorium survive. The vast majority of these commissions were created for export, and the very consistency and longevity of this output attests to a well-organized workshop with a rich supply of models. Belonging to the end of this tradition, this Gospel book opens with a remarkable dedication miniature featuring an unidentified abbot handing the manuscript to St. Peter. As gatekeeper of heaven, Peter holds open a door leading to an altar on which the same book is blessed by the hand of God. By the mid-eleventh century, Reichenau had begun to lose its preferred status as other artistic centers vied for imperial favor.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Reichenau, ca. 1050

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.7, fols. 9v–10r

Purchased by Henry Walters, ca. 1913–1931

St. Peter’s Gospels

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

Around the year 1000, the abbey of St. Peter’s in Salzburg was reformed with the goal of instituting a more disciplined form of monastic life, which found expression in the reinvigorated production of manuscripts like this Gospel book. Sumptuously illuminated by two artists, it was likely used on special feast days. The miniatures respond to artistic developments at centers of monastic reform like Regensburg, Reichenau, and Fulda. The main inspiration, however, was a Gospel book commissioned by Emperor Henry II (973–1024), himself an active reformer, for his new foundation at Bamberg (where it remains today). Against a gold ground, John the Evangelist looks to an eagle, his symbol, which holds open a book. At right, the opening words of his Gospel appear in gold on purple ground (In principio erat verbum; “In the beginning was the word”). Many of the miniatures retain their original protective silk curtains.

"St. Peter’s Gospels,” in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1020

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.781, fols. 188v–189r

Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1933

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Monasteries with imperial patronage enjoyed a relative independence from local oversight. With few exceptions their abbots answered only to the emperor or the pope—a freedom that enabled them to amass considerable wealth and to pursue ambitious programs of artistic production. For most of the tenth century, however, this was not the case in Salzburg—the seat of the Archbishop of Bavaria. Traditionally, the archbishop was simultaneously the abbot of the most important monastery in the region, St. Peter’s. This situation changed dramatically in 987, in response to monastic reform movements that swept throughout the empire, with a goal of instituting a more disciplined adherence to monastic life, free from unnecessary interference.

A monk from Regensburg, named Tito, became the first independent abbot of St Peter’s. He initiated a series of structural changes resulting in the separation of the abbey from the cathedral and its archbishop.

Known as the St. Peter’s Gospels, this manuscript was one of the first major products of the newly reinvigorated scriptorium at St Peter’s and was produced in the final years of Tito’s abbacy. It was likely used on special feast days at the abbey church. Painted by a main artist and an assistant, its miniatures reflect the most recent artistic developments at important reform centers like Regensburg and Reichenau. The artist’s most important model, however, was a book commissioned by Emperor Henry II for his newly founded cathedral at Bamberg--a choice that speaks to the aspirations of the abbey at Salzburg. Shown here is the opening of the Gospel of John, whose portrait, on the left, is set against a solid gold ground. At right are the first words of the Gospel, set against an extravagantly ornamented purple ground.

Gospel Lectionary

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

Generations of painters at Salzburg looked to the “St. Peter’s Gospels” as a source of inspiration. As these foundational miniatures were copied over the decades, a shift toward Byzantine and Italian styles of painting can be observed. The illuminator of this Gospel lectionary took many of his compositions directly from earlier Salzburg manuscripts, but opted for simpler drapery, less modeling, stronger outlines, and a different technique for creating skin tones. The manuscript opens at left with a dedication scene in which an unidentified abbot hands his book to an unidentifiable saint. The miniature at right depicts the Presentation and Betrothal of Mary in the Temple. Crowned by an angel, the young Virgin is presented by her mother, Anna, to her future husband, Joseph. The nude figures atop the two columns are based on the Spinario, an ancient bronze statue from Rome that was famous throughout the Middle Ages.

Gospel Lectionary, in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1030–40

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.44, fols. 1v–2r

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

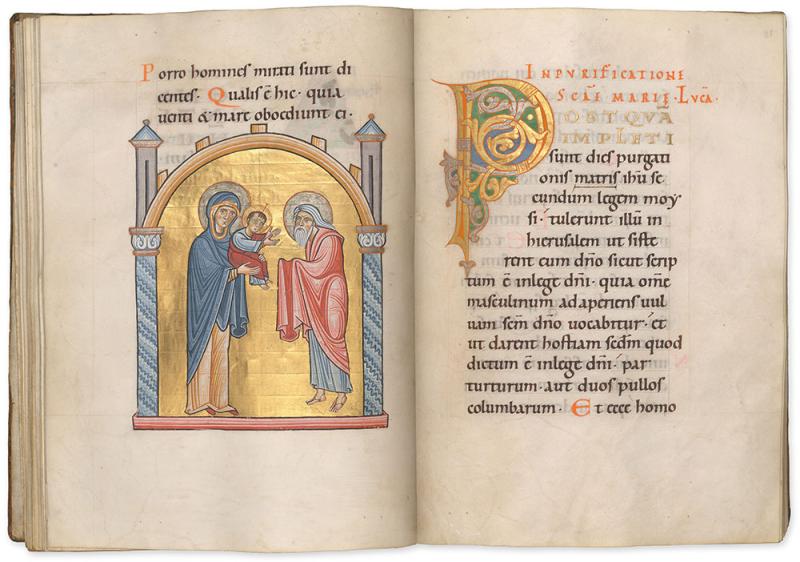

Berthold Lectionary

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

Berthold, the custodian (custos) of St. Peter’s Abbey, identifies himself as the patron and perhaps even the maker of this manuscript in a decorative inscription at the end of the book (at right): “To the key-bearer of heaven [St. Peter] the custodian Berthold, who made this book, offers it with a joyful heart to pay for all his sins. May he who steals it suffer violent bodily pains.” The unusually graphic curse may have been added in response to the politically backed plundering of local monasteries that was occurring at the time. Berthold’s miniatures feature a dramatically flattened style, with monumental figures, starkly rendered outlines, and narrative elements reduced to only the essentials. Each of these developments can be seen in this miniature of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple.

"Berthold Lectionary," in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1080

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.780, fols. 20v–21r

Purchased on the Lewis Cass Ledyard Fund, 1933

Leaf from a Gospel Lectionary

SALZBURG AND THE ART OF REFORM

This leaf once formed part of a Gospel lectionary from Constantinople, written and illuminated around the same time the “St. Peter’s Gospels” was being produced at Salzburg. Pausing after writing the first line of his text, the evangelist Mark is deep in thought. The artist avoids any hint of an architectural setting, allowing viewers to focus instead on the dramatic intensity of the evangelist’s facial expression. The noticeable shift in style at Salzburg may perhaps be attributed to increased trade connections with Venice and northern Italy in the eleventh century, which provided an important link to Byzantium.

Leaf from a Gospel Lectionary, in Greek

Constantinople, early eleventh century

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.530a

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

Imperial Monasteries

12th–14th Century

As monastic reform movements gained momentum throughout the empire, the tenuous relationship between emperor and pope, so carefully maintained by Carolingian and Ottonian rulers, devolved into outright hostility. The trigger was the matter of investiture, the practice of appointing new bishops or abbots. For centuries, emperors and kings reserved the right to install their own candidates in important clerical positions within their realm. However, with the increasing strength of the papacy, along with a growing sense that bishops should not be active in imperial politics, this traditional right became untenable. The ensuing Investiture Controversy (ca. 1076–1122) resulted in a significant weakening of imperial power and a related strengthening of the role of local nobility like the Guelph dynasty, which at its height controlled the duchies of Saxony and Bavaria. In terms of manuscript production, the great age of imperial commissions was largely over. Instead, monasteries began to produce deluxe manuscripts for in-house use or for distribution across their networks. The increased patronage of local nobility, as well as the growing prominence of cathedral schools and universities, meant that book culture itself was changing. New texts were being copied, and new ways of illuminating were being explored.

Gospel Book (MS Ludwig II 3)

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

One of the earliest foundations to flourish in the wake of the tumultuous Investiture Controversy was the Benedictine monastery of Helmarshausen in Saxony. Its abbots acquired important relics from Trier, providing the impetus for new building campaigns as well as promoting manuscript production. This Gospel book is an early witness to the monastery’s cultural vitality. Its inventive evangelist portraits combine new styles of painting from the Rhine-Meuse region with local Saxon traditions. The portrait of Luke is rendered in strong outlines, with drapery characterized by nested V-folds and modeling achieved through heavy bands of shading. In contrast to these innovations, the simulated textile designs of the facing page refer directly to the abstract tradition of painting cultivated at nearby Corvey in the tenth century.

Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Helmarshausen, ca. 1120–40

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS Ludwig II 3, fols. 83v–84r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

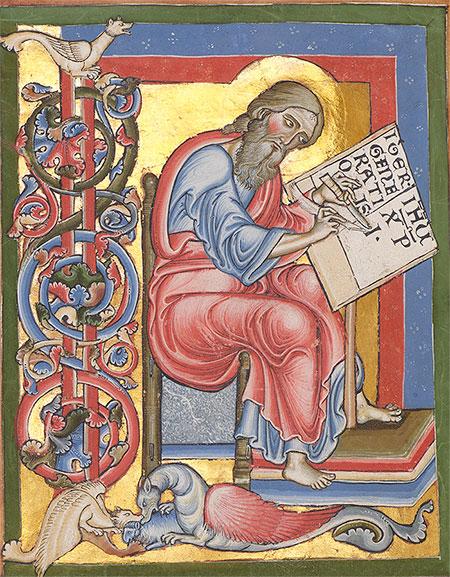

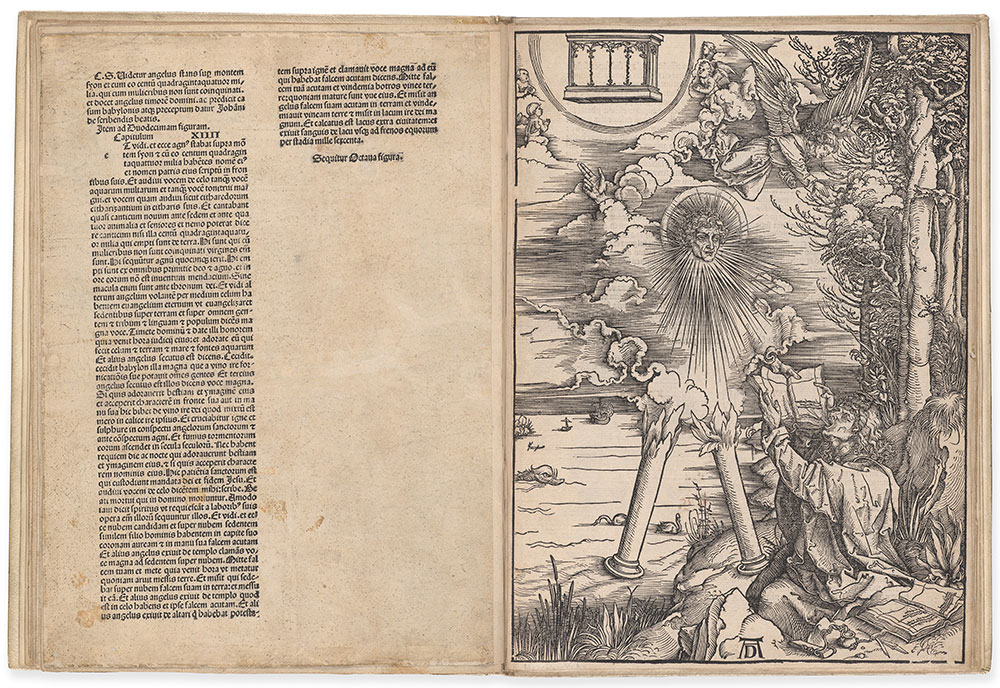

Heiningen Gospels

Although monasteries produced the majority of manuscripts in the twelfth century, the task of illuminating these works did not always fall to monks. For prestigious commissions, monasteries could seek out professional painters, who traveled widely in search of work. This Gospel book was illuminated by two artists. The first was a monk of Hamersleben; the second, whose work is shown here, was a professional painter with a strikingly different style. The figure of the evangelist Matthew has been endowed with a thoughtful expression and dramatic drapery. He appears to occupy three-dimensional space, an effect heightened by contrasts between the varied surfaces. In these respects, the illuminator demonstrates firsthand knowledge of contemporary artistic developments across the continent. The pastiche book box (above), in which the manuscript was stored, combines thirteenth-century elements with nineteenth-century additions, such as the large plaque of Christ at center.

"Heiningen Gospels" (Fragment), in Latin

Germany, Hamersleben, ca. 1170 and ca. 1200 (manuscript)

Germany, Saxony, thirteenth century, and France, Paris, nineteenth century (book box)

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.565, fol. 13v

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1905

Stammheim Missal

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

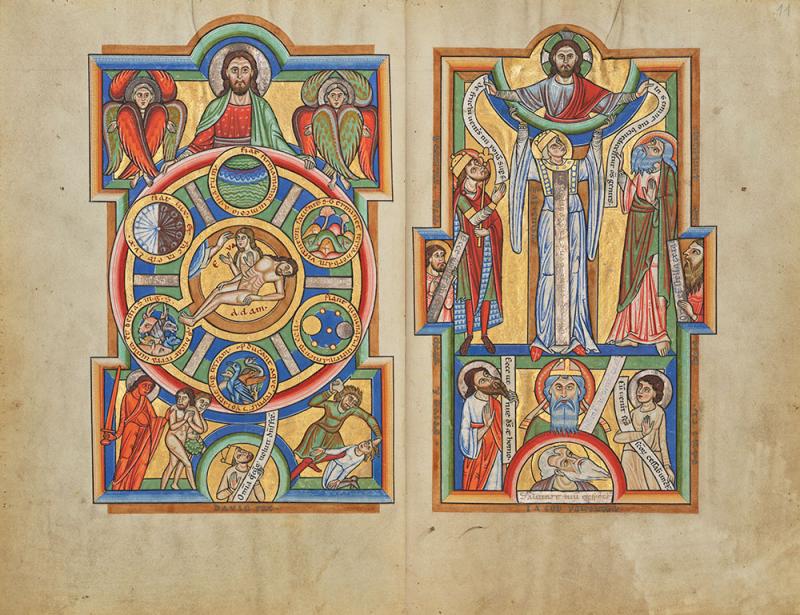

In the twelfth century, monks at the Benedictine monastery of St. Michael advocated for the canonization of their founder, Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim (d. 1022). These efforts coincided with a flurry of artistic activity, including the production of spectacularly illuminated manuscripts—among them, this missal. By depicting the story of salvation, the prefatory cycle shapes viewers’ understanding of the manuscript’s contents. The radially organized Creation miniature, at left, focuses on the plight of Adam and Eve, who are encircled by representations of the six days of Creation. Their expulsion from paradise and the story of Cain and Abel, below, indicate the sinful state of humankind. The facing miniature, in contrast, represents the promise of salvation. At center, a personification of divine wisdom holds up Christ amid Old Testament figures who prophesize his incarnation.

"Stammheim Missal,” in Latin

Germany, Hildesheim, ca. 1170

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS 64, fols. 10v–11r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Around the middle of the twelfth century, monks at the Benedictine monastery of St. Michael at Hildesheim, in Lower Saxony, were advocating for the canonization of their famed eleventh-century founder—Bishop Bernward, who was a great patron of the arts as well as the tutor of Emperor Otto III. As part of this effort, the monks initiated a flurry of artistic activity that included building renovations and the production of spectacularly illuminated manuscripts such as this mass book, known as the Stammheim Missal. With fifteen full-page paintings and well over a dozen half-page decorative initials, this manuscript is among the most sophisticated and richly illuminated books of its time.

After a splendid calendar, the Stammheim Missal opens with a prefatory cycle of three miniatures depicting Creation, Divine Wisdom, and the Annunciation. The complex compositions of this opening cycle provide the viewer with a theological framework for understanding the contents of the manuscript. The first miniature, at left, focuses on the creation of Eve from Adam’s side. Around them are the six days of Creation. The scenes below depict their expulsion from Paradise and the subsequent story of Cain and Abel, both indicative of the sinful state of humankind.

If the first miniature emphasizes the Fall from Grace, the facing page represents the promise of salvation. At center, a personification of Divine Wisdom holds up a figure of Christ. They are surrounded by Old Testament kings, prophets, and patriarchs. Taken together, these figures present the coming of Christ as the fulfillment of Old Testament prefigurations. On the next page, Christ’s incarnation is depicted with the miniature of the Annunciation.

This approach of presenting events from the Christian New Testament as the fulfillment of prophecies from the Hebrew Bible is known as typology, and it was a central feature of monastic art in the twelfth century.

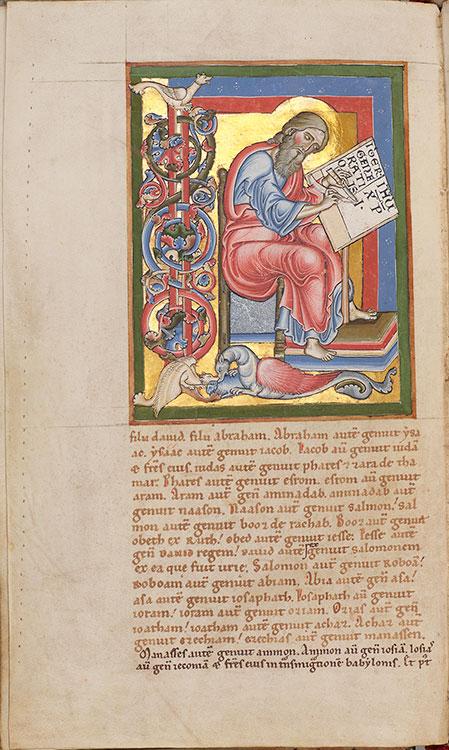

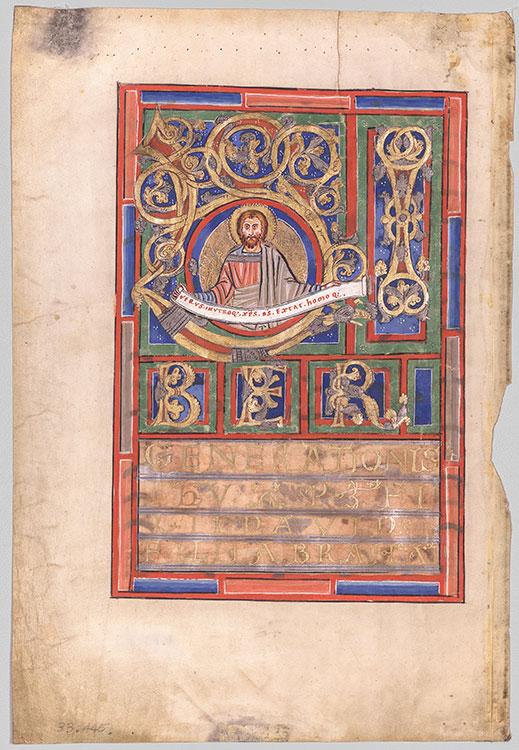

Leaf from a Gospel Book

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

This leaf once formed part of a magnificent Gospel book, written and illuminated at Helmarshausen, but perhaps made for the monks at Corvey. Originally positioned at the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel, the leaf features a depiction of Christ embedded within the very first word, Liber (book). Through its inscription (verus in utroque deus extat homoque; “truly he exists as both man and god”), Christ’s scroll emphasizes the dual nature of his incarnation, while the very placement of the figure, inhabiting the sacred text, visualizes the link between Christ and the word of God.

Leaf from a Gospel Book, in Latin

Germany, Helmarshausen, ca. 1190

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchased on the J. H. Wade Fund, 1933.445

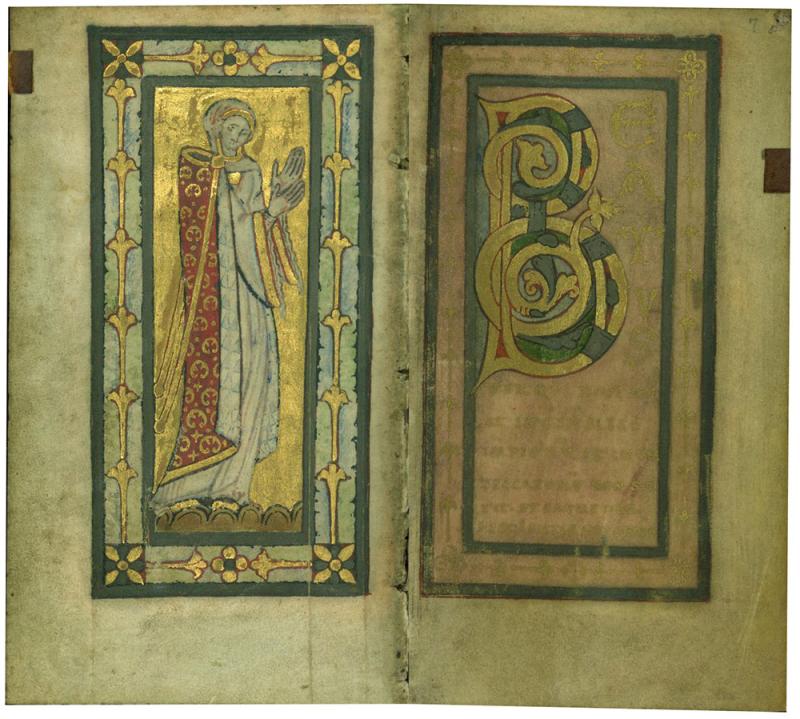

Psalter (MS W.10)

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

The scriptorium at Helmarshausen regularly exported both manuscripts and artists to nearby Paderborn and Corvey, and even to centers as far as Scandinavia. In the second half of the twelfth century, however, this pattern of patronage changed as local nobility began to commission works directly from the monastic scriptorium. An early example of this trend, this diminutive psalter was likely made for a local Guelph princess—perhaps Gertrud (ca. 1152–1197), the daughter of the duke of Saxony and a future queen of Denmark. Dressed in red brocade lined with ermine, she raises her hands in prayer. The object of her devotion, depicted on a now-lost facing page, was likely the Virgin Mary.

Psalter, in Latin

Germany, Helmarshausen, ca. 1160–70

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.10, fols. 6v–7r

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

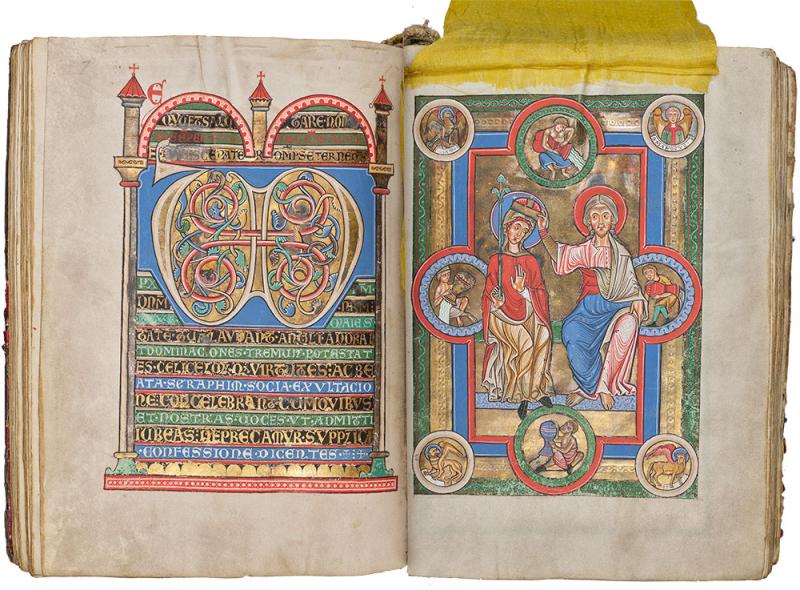

Berthold Sacramentary

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

In 1215, fire consumed the monastery at Weingarten. Major relics were lost, and the abbey church had to be rebuilt. In this context of renewal, Abbot Berthold engaged a professional painter—known as the Berthold Master—who illuminated a new set of liturgical books, chief among them this magnificent Mass book. The miniature for the feast day of St. Oswald, at left, depicts the saintly king of Northumbria seated next to Bishop Aidan of Lindisfarne. According to legend, Oswald gave so charitably to the poor that the bishop blessed the king’s generous hand. The hand never aged, becoming a wonder-working relic after his death. Emphasizing the miraculous qualities of Oswald’s relics, this full-page miniature promotes the cult of one of Weingarten’s patron saints. The manuscript preserves its original curtains and treasure binding.

"Berthold Sacramentary," in Latin

Illuminated by the Berthold Master

Germany, Weingarten, ca. 1215–17

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.710, fols. 101v–102r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1926

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

In the decades around 1200, pilgrims began to arrive at the Abbey of Weingarten, in Swabia, to venerate an extraordinary relic of Christ’s blood, which was donated by Judith of Flanders, the duchess of Bavaria and a great patron of the arts. Coinciding with this rise in pilgrimage, Berthold, the abbot of Weingarten, undertook an ambitious program of cultural production to reinforce the abbey’s new status as a religious center of international renown. Berthold’s leadership was tested when a catastrophic fire destroyed the monastery in 1215. Despite significant losses, the abbot was able to rededicate his church in just a few years. It is in this context of renewal and revitalization that Berthold engaged a professional painter to illuminate a new set of liturgical books for the monastery.

This magnificent mass Book represents Berthold’s most important commission. Shown here is the miniature for the feast of St Oswald, an obscure English saint who was initially not highly esteemed at Weingarten. Nevertheless, his relics formed part of Judith’s donation and Berthold made a conscious effort to raise the saint’s profile after the relics of other saints were destroyed in the fire. The use of colorful embroidered repairs, one of which you see on the margin of the right page, was part of a broader effort to make the manuscript appear older than it actually was. In a similar manner, the manuscript’s magnificent jeweled cover harks back to the age of Carolingian treasure bindings like the Lindau Gospels.

With its spectacular paintings and its range of precious materials from gold and gems to textiles and relics, the Berthold Sacramentary marks a high point of monastic book production. Moreover, as a prestigious memorial object, intimately tied to the abbey’s history and its self-image, the manuscript both celebrated and legitimized the forms of devotion so carefully promoted by Abbot Berthold.

Hainricus Missal

THE MONASTIC SCRIPTORIUM

After a burst of activity, the Berthold Master vanished from Weingarten without a trace. Just a few years later, a second professional artist took his place and painted miniatures for an important commission from a high-ranking member of the abbey: this Mass book for the sacristan Henry (Hainricus) to use in a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which he was responsible for maintaining. Placed unusually at the core of the manuscript just before the Eucharistic prayer, the Coronation of the Virgin, at right, attests to Henry’s devotion to Mary. The surrounding symbols of the four evangelists and four rivers of paradise underscore her central role in the universal Church. The manuscript preserves its original treasure binding, silk curtains, and remarkable thirteen-strand bookmark.

"Hainricus Missal" (Gradual, Sequentiary, and Sacramentary), in Latin

Germany, Weingarten, ca. 1220–30

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.711, fols. 56v–57r

Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1926

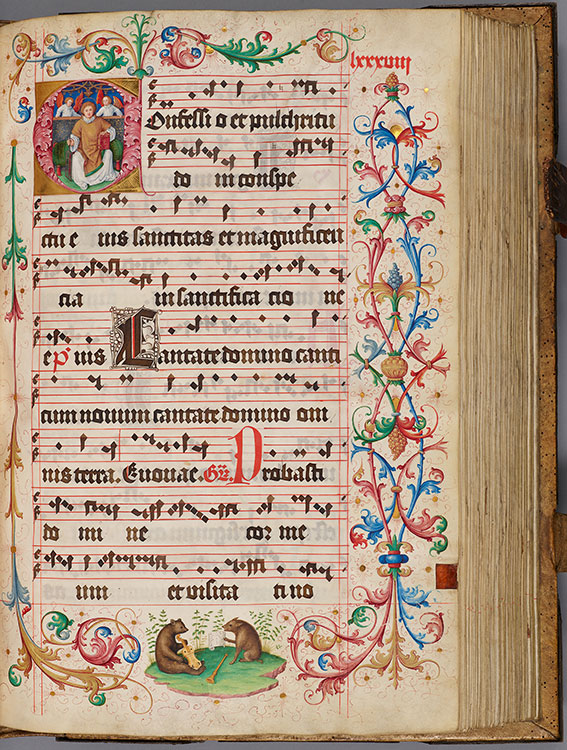

Leaf from the Wettingen Gradual

RITE AND RITUAL

This monumental leaf from a choir book testifies to the ambition of the monks who commissioned it. With such commissions, newer mendicant orders like the Augustinians sought to place themselves on par with older foundations like the Benedictines. The illuminator responsible for this leaf worked in a manner derived from the latest fashion at the French court. Arranged from bottom to top like a stained-glass window, four scenes fill the initial I. They depict Augustine teaching; the dream of his mother, Monica; his baptism; and, finally, Bishop Augustine instructing monks. The scroll “spoken” by the monk in the lower margin reads, “Pray for us, blessed Father Augustine.”

Leaf from the “Wettingen Gradual,” in Latin

Germany, Cologne, ca. 1330

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchased on the Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1949.203

Homilary

RITE AND RITUAL

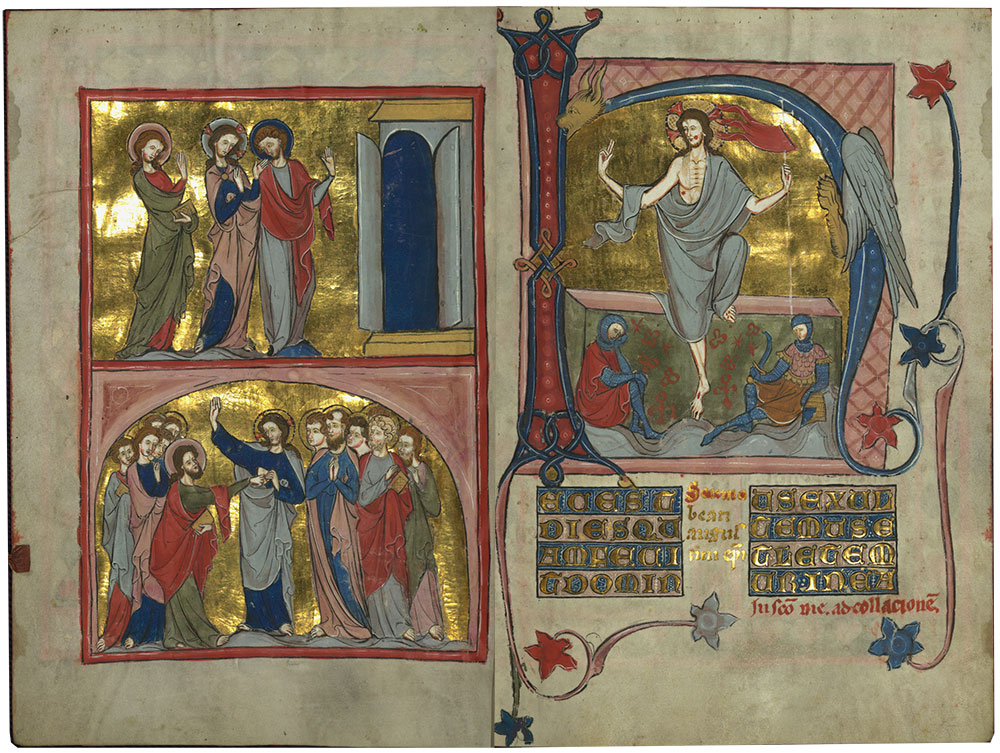

In its profuse use of gold, whether in the burnished backgrounds or the display scripts, this collection of homilies emulates the lavish aesthetic of imperial manuscripts of the early Middle Ages, despite its adoption of Gothic conventions. The homilary—a collection of sermons—was made for and in part by a community of Cistercian nuns. A reform order, the Cistercians traditionally eschewed such luxury, but not here. In its monumentality, the grand initial of the Resurrection rivals that of the full-page miniature on the facing page, which depicts two of Christ’s appearances to the apostles after his Resurrection: Christ as a pilgrim on the road to Emmaus and the Doubting Thomas.

Homilary, in Latin

Germany, Westphalia, ca. 1330

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.148, fols. 45v–46r

Purchased by Henry Walters, before 1931

Joshua O'Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

This richly painted book contains a collection of sermons for use during the Easter season. It is part of a pair, of which the other volume—now in Oxford—gathers together sermons for Christmas time.

Both manuscripts were made for a Cistercian convent in Westphalia, a region in northwestern Germany. In the High Middle Ages, the Cistercians were celebrated for their austerity, which led them to reject all forms of luxury, including the visual arts. In this book, however, no trace of such restraint remains.

A team of at least three professional artists painted most of the miniatures. Set against sheets of burnished gold, their elegant, elongated figures reflect the latest developments in painting from France. Shown here, at left, are two scenes that demonstrate Christ’s resurrection: above, is Christ on the Road to Emmaus, where he appears to two apostles who previously thought him dead; below is the Doubting Thomas, who needed physical proof that Christ had risen from the dead, and thus presses his finger into the wound in Christ’s side. At right, filling the oversized initial H, is the Resurrection itself. Two small soldiers are shown sleeping as Christ rises from the tomb. The composition evokes statues of the Resurrection that were a common fixture of Cistercian convents in Westphalia and played an important role in the Easter liturgy, as did this manuscript.

Gold is also used for the display scripts and the massive frames that adorn nearly every page of the manuscript. Several of these text pages were painted by the nuns for whom the manuscript was made. The extravagant use of gold represents just one of a number of archaic features that appear to have been deliberately adopted to evoke the lavish commissions characteristic of imperial female foundations of the earlier Middle Ages.

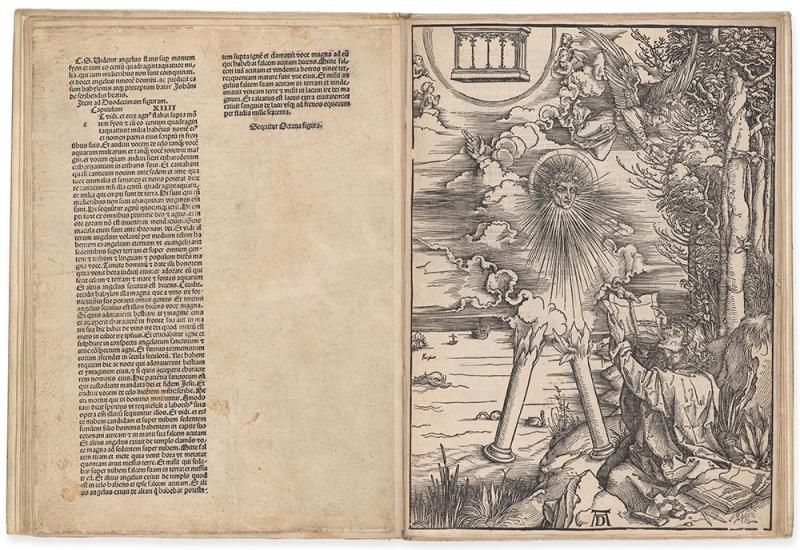

Leaf from an Apocalypse

RITE AND RITUAL

This large leaf, one of several surviving from a dismembered picture book of the Apocalypse, depicts John the Evangelist as the author of the book of Revelation, surrounded by seven angels representing the seven churches. The tabernacles and pinnacles around the angels evoke the façade of a Gothic cathedral, just as the blue-and-red palette suggests a stainedglass window. While it depicts the kingdom of heaven, the full-page miniature also represents the towering ambition of the high medieval Church. Didactic picture books of this kind had represented a popular genre in German monasticism since the twelfth century.

Leaf from an Apocalypse

Germany, Hessen, ca. 1340–50

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS 108

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011

Leaf from a Missal (MS M.892.2)

RITE AND RITUAL

Set against a gold background, a priest elevates a Eucharistic host within an initial C marking the beginning of the Feast of Corpus Christi. Behind him stand a deacon and a subdeacon holding a paten (plate). As this Mass celebrates the real presence of Christ in the Eucharistic offering, the most prominent detail is the monstrance (receptacle) at the corner of the altar, displaying a consecrated host. Unusually for a Mass book, the bottom margin is filled with animal scenes humorously depicting a world upside down. This missal was painted by Master Bertram, a well-documented artist in Hamburg whose workshop also produced panel paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts.

Leaf from a Missal, in Latin

Illuminated by Master Bertram (ca. 1340–1415) for Johann von Wustorp (d. 1381)

Germany, Hamburg, before 1381

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.892.2

Gift of the Fellows, 1958

Liturgical Set

RITE AND RITUAL

This deluxe liturgical set, likely commissioned by an abbot of St. Trudpert, was created by a lay goldsmith from Freiburg named Master John (Johannes), who ran an active workshop in the thirteenth century. The chalice, paten, and straw (to prevent spilling) were essential vessels used by a priest for the consecration of the Eucharist, the moment in Mass when the offering of bread and wine was ritually transformed into the body and blood of Christ. The rich visual program is typological: Old Testament prophecies at the base of the chalice are paired with New Testament scenes around its node (middle part). The use of typology continues on the paten, where Abel and Melchisedech serve as prefigurations of Christ as both sacrifice and celebrant.

Liturgical Set from the Abbey of St. Trudpert at Münstertal

Germany, Freiburg im Breisgau, ca. 1230–50

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Cloisters Collection, 1947.101.26–28

Lichtenthal Altar Tabernacle

RITE AND RITUAL

This tabernacle was commissioned by Sister Margaret (Greda) Pfrumbon, whose family made several gifts to the Cistercian convent of Lichtenthal in the Rhineland, where she was a nun. Margaret appears alongside St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the famous monastic reformer and a fellow Cistercian. Like the three magi, Margaret offers her gift to the Virgin and Child. With its translucent enamel over an engraved ground, the tabernacle emulates stained-glass windows. The baldachins placed over angels on each corner of the tabernacle resemble those at Reims Cathedral, the coronation site of French kings. The lions serving as feet for the object link the tabernacle to the Temple of Solomon, the archetypal site of the Holy of Holies.

"Lichtenthal Altar Tabernacle"

Germany, Upper Rhine (?), ca. 1330

The Morgan Library & Museum, AZAZ 48

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1908

Speculum virginum (Mirror of Virgins)

MONASTIC LEARNING AND REFORM

The Mirror of Virgins, a book instructing clerics in the spiritual care of nuns, exemplifies the changing status of visual imagery within monastic reform movements. The “mirror” of the title defines the text as a place where readers can examine the “face of their hearts.” A dialogue between a monk (Peregrinus) and a nun (Theodora), the work contains a dozen narrative, allegorical, and diagrammatic images that serve as instruments of pastoral care. The Trees of Vices and Virtues dominate one opening to the near exclusion of text. The text directs “novices and the untutored” toward these “two little trees,” so that “anyone studying to improve himself can clearly see what things will result from them.”

Conrad of Hirsau

(ca. 1070–ca. 1150)

Speculum virginum (Mirror of Virgins), in Latin

Germany, Himmerod, ca. 1200–1225

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MS W.72, fols. 25v–26r

Purchased by Henry Walters, 1903

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

No work better exemplifies the changing status of visual imagery within monastic education than the Mirror of Virgins, a book of spiritual instruction for nuns written between 1130 and 1140. The manuscript’s use of tinted line drawings is characteristic of didactic works of monastic instruction within the context of twelfth-century efforts to reform monasticism by raising educational (and moral) standards. The author of the text, who was most likely from Hirsau, an important center of reform monasticism, refers to the mirror of the book’s title as a place where readers can examine the “face of their hearts.”

This early thirteenth-century copy was created at Himmerod, a monastery founded in 1134 by Bernard of Clairvaux. Despite Bernard’s well-known hostility to images, the monks there quickly came to consider them indispensable in certain contexts such as the pastoral care of nuns.

Constructed as a dialogue between a monk (Peregrinus) and a nun (Theodora), the Mirror includes a dozen narrative, allegorical, and diagrammatic drawings that aid in spiritual guidance and education. The Trees of the Vices and Virtues dominate the opening displayed here to the near exclusion of the main text. Whereas the branches of Vice, on the left, hang downward toward the Whore of Babylon, the Virtues, on the right, rise up from Jerusalem and Humility. Atop the Virtues, Christ stands as the “New Adam,” in contrast to the “Old Adam” whose fall was rooted in pride.

Underscoring the identification of the Tree of Vices with the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, two serpents coil around the trunk. The text directs “novices and the untutored” toward these “two little trees,” so that “anyone studying to improve themselves can clearly see what things will result from them.”

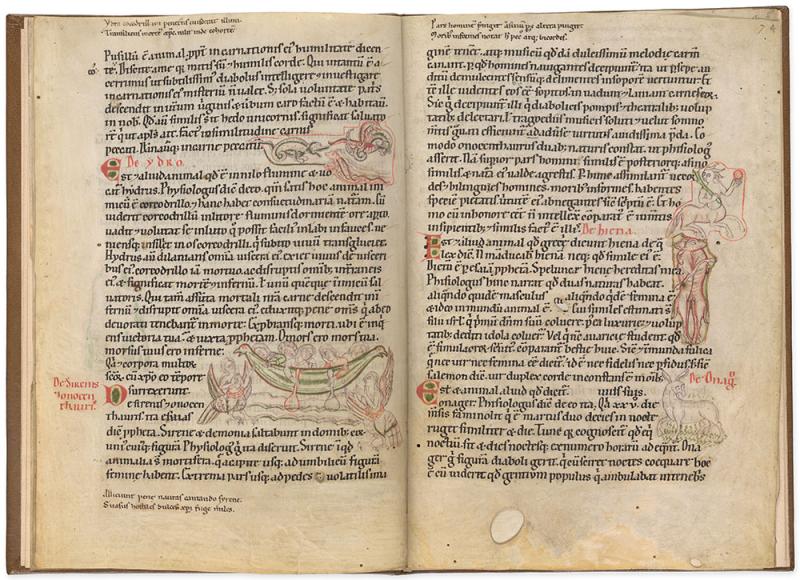

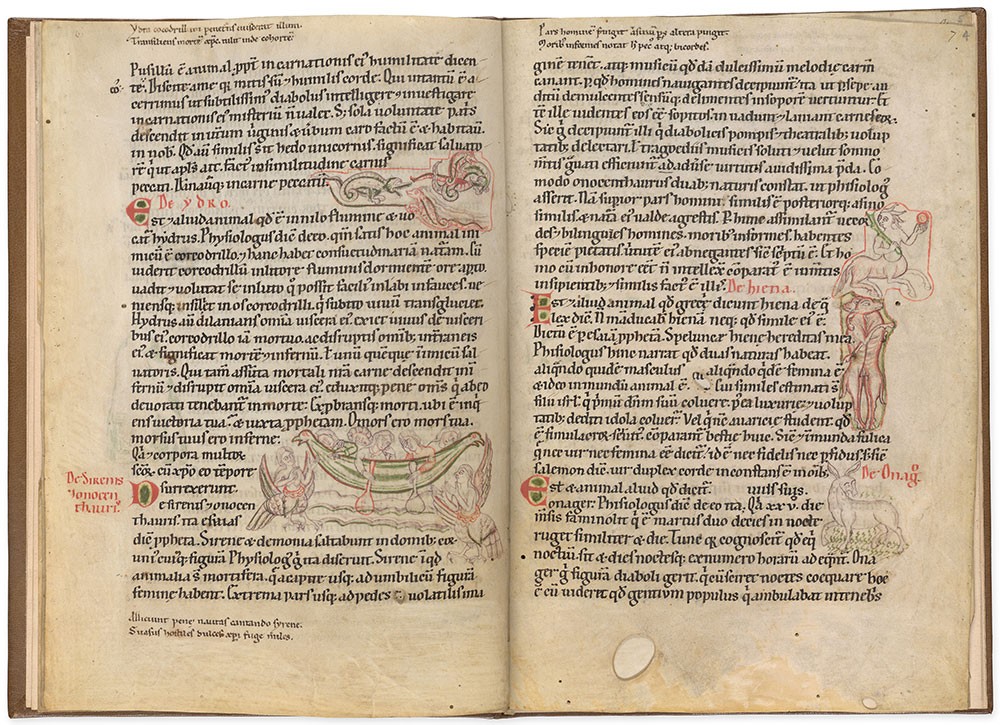

Bestiary

MONASTIC LEARNING AND REFORM

Monastic learning included texts on the natural world. A characteristic example from the important Benedictine monastery at Göttweig, this compilation of animal lore is based on ancient and early medieval sources. Beginning with the lion and ending with the phoenix, the text describes some thirty different animals, both real and imaginary. At upper left is the hydrus, legendary enemy of the crocodile; directly below are sirens, birdlike beasts that prey on sailors. At upper right is the onocentaur, a half-man, half-donkey hybrid; below that are sex-changing hyenas, related to sodomy; and the creature at lower right is a braying onager, symbol of the devil. Added later, rhyming couplets in the margins offer typological and moral interpretations of the animals, of a type also featured in the encyclopedic Concordance of Charity.

Bestiary (Dicta Chrysostomi), in Latin

Austria, Göttweig, ca. 1140–50

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.832, fols. 3v–4r

Gift of the Fellows, 1958

Leaf from a Schoolbook

MONASTIC LEARNING AND REFORM

This delicate drawing exemplifies the educational program of medieval monasticism. Personified liberal arts (branches of learning) descend from a magisterial figure of Philosophy. She is depicted as the queen of heaven, crowned and holding a scepter, flanked by personifications of the sun and moon and surrounded by stars and clouds, as if a celestial vision. Reminiscent of Pentecost imagery, seven streams flow from her breast, nourishing each of the liberal arts. The double-sided drawing marries principle to practice; whereas the arts are personified as women, on the reverse, their practitioners are presented as famous men.

Leaf from a Schoolbook, in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1150–60

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.982

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, with special gifts of the Glazier Fund, Dr. Ruth Nanda Anshen, Mrs. Harold M. Landon, and Miss Julia P. Wightman, 1978

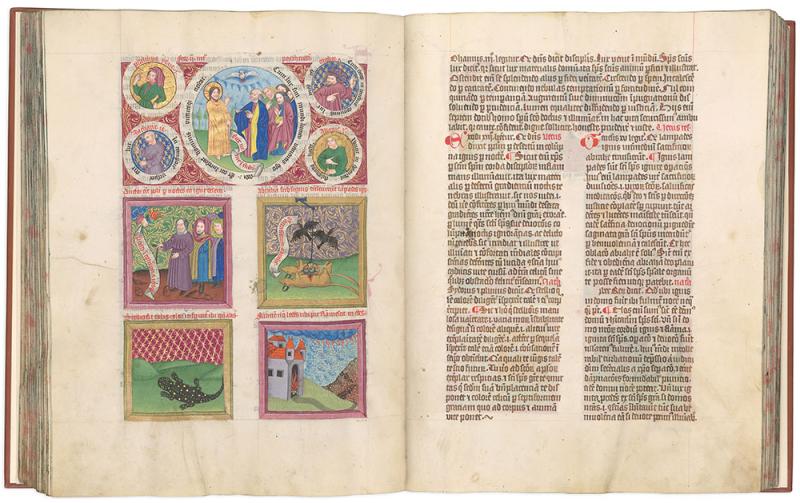

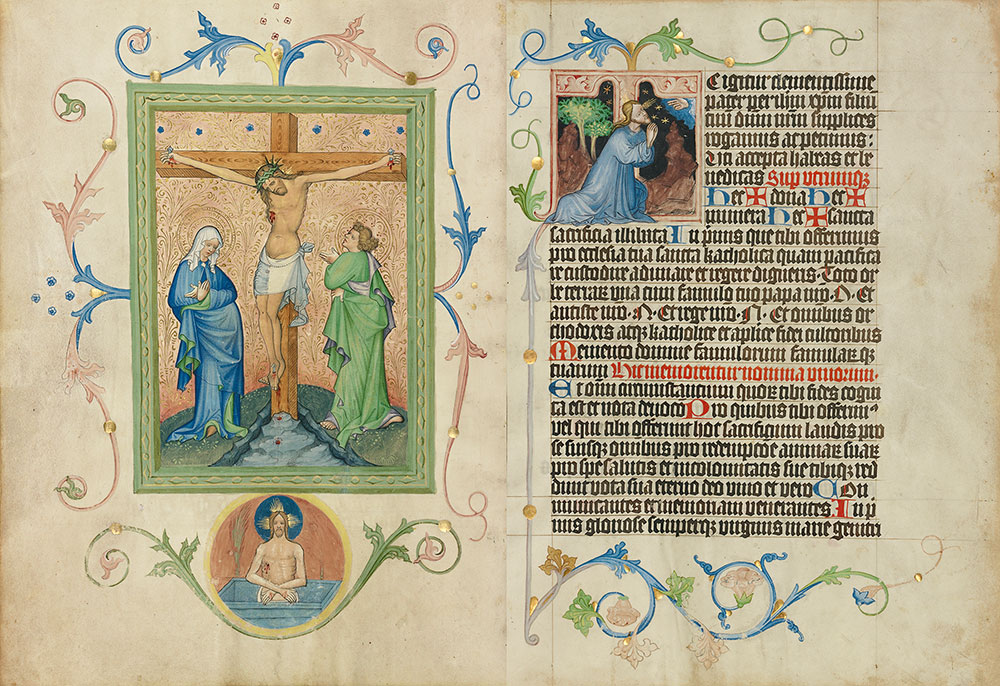

Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation)

HISTORIES OF SALVATION

The Mirror of Human Salvation was composed in northern Italy but enjoyed its widest dissemination north of the Alps. Juxtaposing scenes from the New Testament with Old Testament prefigurations, the images offer a lesson in the shape of sacred history and the nature of memory and meditation. In the first image, Mary mourns under the cross, surrounded by events on which she, as a model for the viewer, reflects. Her pose is echoed in the three prefigurations that follow: Anna is perturbed by the absence of her son, as was Mary when she could not find Jesus. The woman from the parable of the lost coin likewise stands for Mary’s loss of her son. Finally, Saul forces his daughter Michal to marry Phalti when David goes into hiding.

Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation), in Latin

Germany, Franconia (Nuremberg?), ca. 1350–1400

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.140, fols. 37v–38r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1902

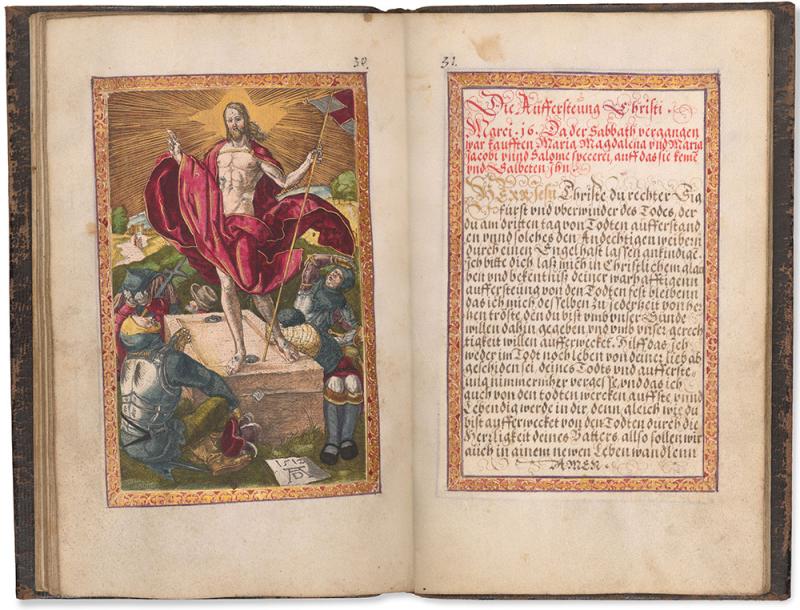

Biblia pauperum (Paupers’ Bible)

HISTORIES OF SALVATION

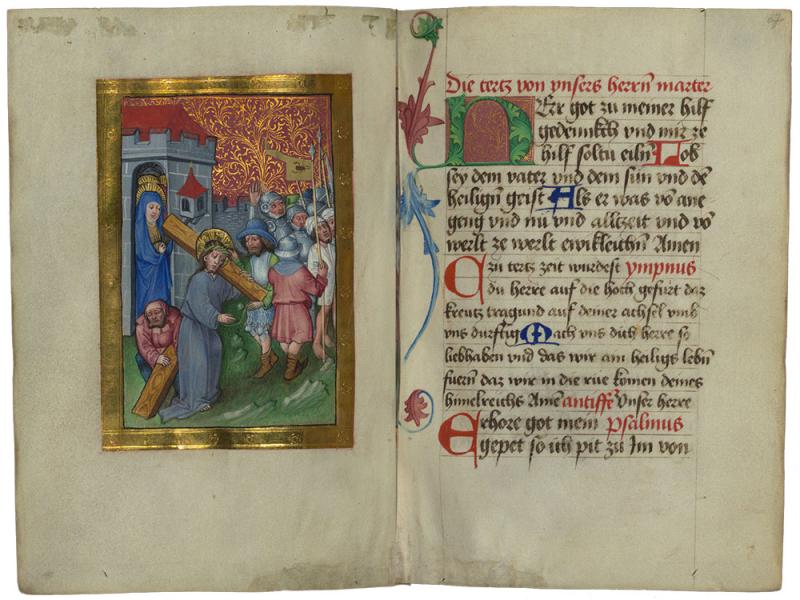

Pointing out the links between the Old and New Testaments constituted a staple of Christian commentary on the Bible. Despite its name (a misnomer), the Paupers’ Bible circulated primarily in Benedictine and Augustinian monasteries in Austria and Bavaria. Configurations varied, but in this unfinished copy, each page features four Old Testament prophets surrounding a New Testament subject, with a pair of Old Testament scenes below. At left, for example, the Crowning with Thorns is paired with the Shaming of Noah and the Mocking of Elijah. At right, Christ Carrying the Cross is related to Abraham and Isaac as well as Elijah’s Encounter with the Widow of Zarephath. Added much later, the inscriptions represent an attempt to finish the manuscript.

Biblia pauperum (Paupers’ Bible), in German

Germany, Regensburg, ca. 1435

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.230, fols. 14v–15r

Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906

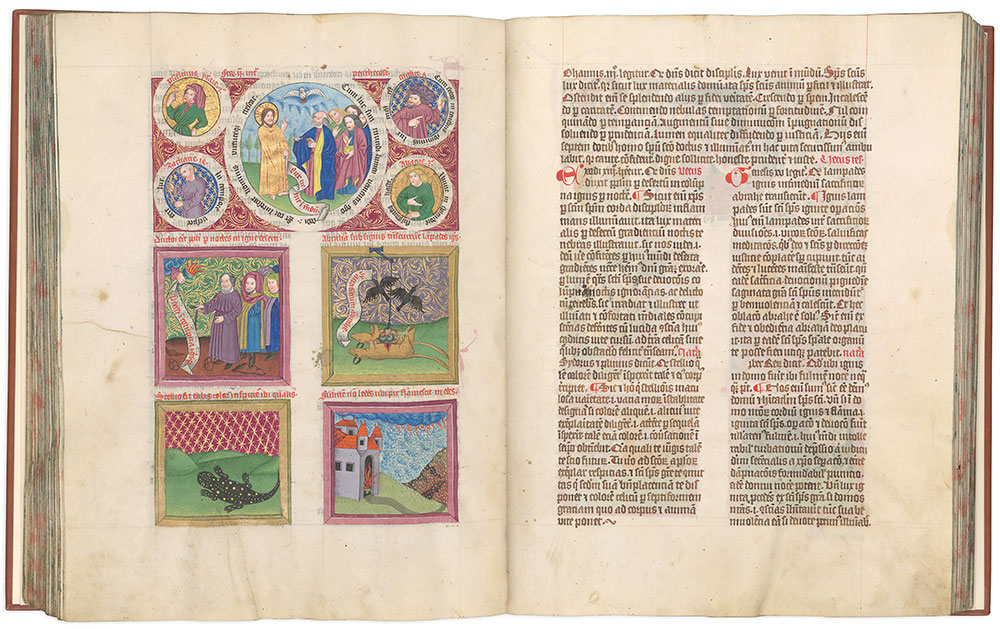

Concordantia caritatis (Concordance of Charity)

HISTORIES OF SALVATION

This compendium systematically links prefigurations from the Old Testament and the natural world to their Christian realizations in the New Testament. At top, for example, the principal scene is Christ telling Nicodemus that light has come into the world. Directly below are two scriptural prefigurations: Moses and the Israelites led by a pillar of fire, and God’s covenant with Abraham. There follow two examples from natural history: a chameleon, and a burning house in a hailstorm. Just as the lizard takes on the color of its surroundings, so an observer can adopt exemplary behavior. Just as hail and lightning cannot harm a blazing house, so the Last Judgment cannot harm one ablaze with the Holy Spirit. This opulent copy was made for Leonhard Dietersdorfer, a cleric and imperial notary from Salzburg.

Ulrich of Lilienfeld

(ca. 1308–1358)

Concordantia caritatis (Concordance of Charity), in Latin and German

Austria, Vienna, ca. 1460

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.1045, fols. 120v–121r

Gift of Clara S. Peck, 1983

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

The Concordance of Charity, written between 1345 and 1351 by Ulrich, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Lilienfeld in Austria, represents the most ambitious handbook of its kind from the Middle Ages. Typological in character, the work follows the liturgical calendar. Employing types drawn from nature as well as Scripture, it incorporates a moralized bestiary into an exposition of salvation. With 248 groups of images totaling over 1,000 illustrations, it is no wonder that this opulently decorated copy commissioned by Leonhard Dietersdorfer—a cleric and notary of Salzburg as well as a master of theology—was never completed.

At the top of the page exhibited here, four prophets surround the principal subject: Christ telling Nicodemus that light has come into the world a scene selected for the Monday after Pentecost.

The lower part of the page presents four types: Moses and the Israelites led by a pillar of fire and God’s covenant with Abraham. Having been asked to sacrifice a heifer, a goat, a ram, a dove, and a pigeon, Abraham cuts them all but the fowl in half. Birds of prey descend and are driven away. Then, after sunset, “there arose a dark mist, and there appeared a smoking furnace and a lamp of fire.” The artist condenses all this into a single miniature in which the furnace and lamp hang from a hook projecting from the upper frame. Connecting both images to Pentecost is the common theme of fire descending from the heavens.

Lower still are two types drawn from natural history: on the left a chameleon; on the right, a burning house in a hailstorm. Just as the lizard takes on the color of its surroundings, so too an observer adopts the exemplary behavior of someone he sees. And just as hail and lightening do not endanger a house that is already ablaze, so the Last Judgment cannot endanger someone whose heart is already ablaze with the fire of the Holy Spirit.

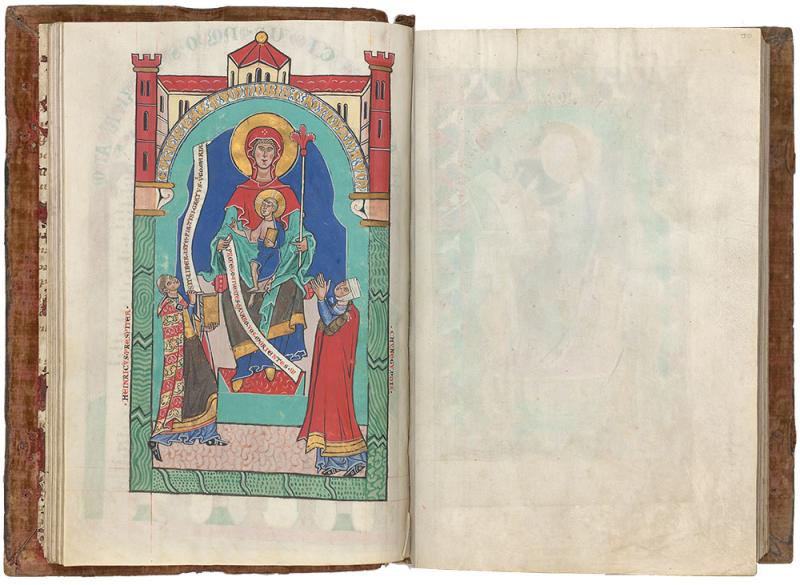

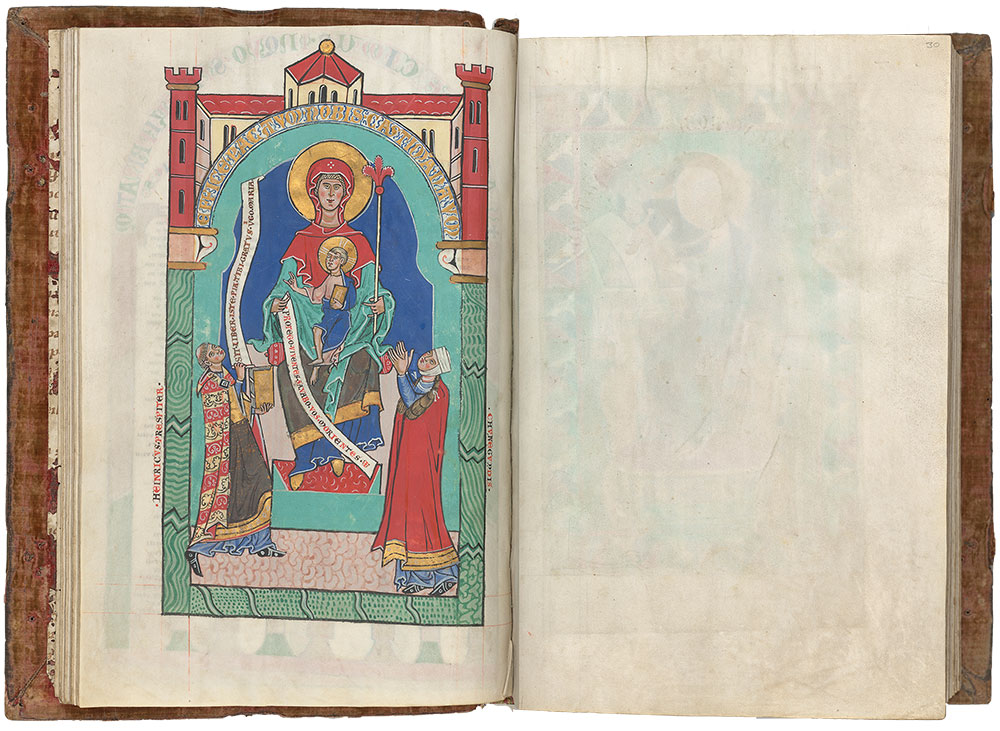

Seitenstetten Gospels

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Established in 1112 by a local count, Udalschalk von Stille, and his brother-in-law, Reginbert, the monastery at Seitenstetten actively commemorated its founding dynasty for well over a century. When Abbot Henry (r. 1247–50) commissioned a deluxe Gospel book for the monastery, his aristocratic patrons were featured prominently in its decorative program, as was Henry himself. In the dedication miniature shown here, Henry (Heinricus) and a noblewoman offer their book to an enthroned Virgin and Child. Henry is identified as a priest, suggesting that this commission may slightly predate his rule as abbot. The woman is identified as Cunigunde (Chunegundis), who is attested in contemporary sources as the widow of Otaker von Stille and thus a member of the dynasty.

"Seitenstetten Gospels," in Latin

Austria, Seitenstetten (?), ca. 1247

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.808, fol. 29v

Purchased, 1940

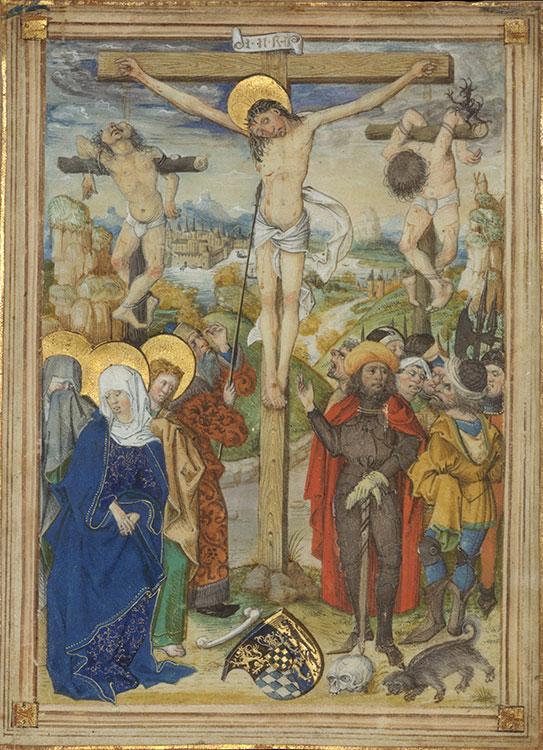

Seitenstetten Missal

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

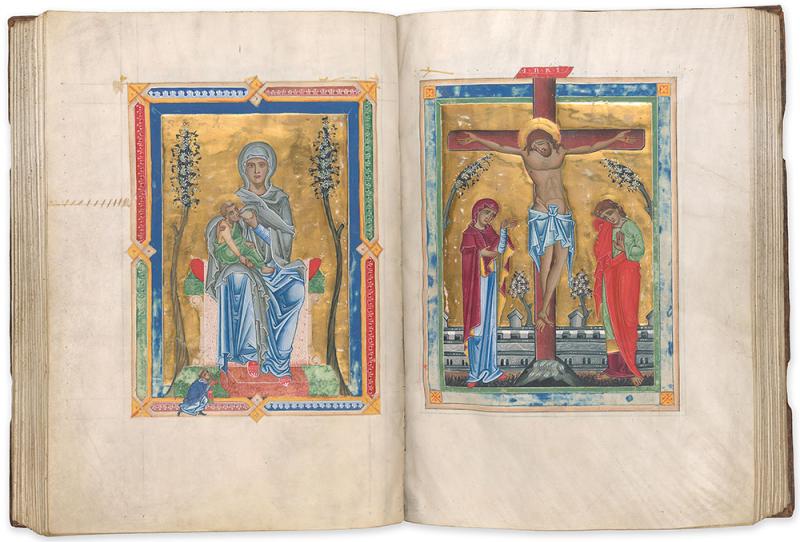

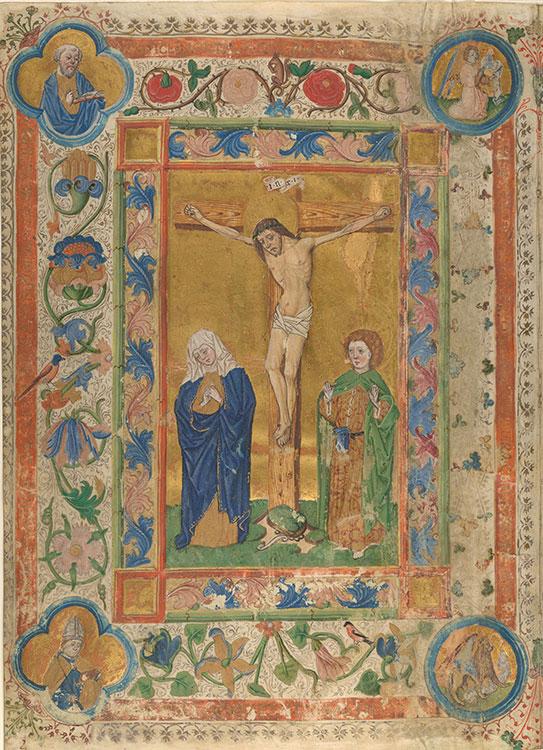

In 1254, the monastery at Seitenstetten burned to the ground. Circumstances were so dire that the archbishop of Salzburg intervened, granting indulgences, or the forgiveness of sins, for anyone offering financial support to the monks. As the well-connected son of the duke of Silesia, Archbishop Ladislaus (ca. 1237–1270) came to Salzburg via Padua, where he had studied at the renowned university. He likely played a role in the commissioning of this missal, coinciding with the rededication of the monastery. Of the manuscript’s three local artists, the one responsible for this diptych of the Virgin and Child with a facing Crucifixion demonstrates firsthand knowledge of contemporary Paduan painting, which must have been facilitated by the archbishop’s connections. The donor at the foot of the Virgin is likely the abbot of Seitenstetten.

"Seitenstetten Missal" (Gradual, Sequentiary, Sacramentary), in Latin

Austria, Salzburg, ca. 1265

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.855, fols. 110v–111r

Purchased from Mrs. Edith Beatty, 1951

Leaf from the Arenberg Psalter

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Arranged in a double-tiered format, this leaf from a deluxe psalter depicts the Flagellation of Christ and the Crucifixion set against a solid gold background. The unusual frame heightens the drama of the narrative. Grammatical clues in the manuscript’s Latin prayers indicate that it was created for a woman, perhaps as a gift for the wedding of Helen, the daughter of Duke Otto of Brunswick, to Hermann II of Thuringia. This book marks the emergence of a new style of painting known as Zackenstil (Zigzag style), derived in part from Byzantine and Venetian art, and characterized by thick, jagged folds of drapery that defy gravity. This new style spread quickly throughout the empire, becoming a standard mode of figural representation across all artistic media.

Leaf from the “Arenberg Psalter,” in Latin

Germany, Hildesheim, ca. 1239

Art Institute of Chicago

Purchased on the S. A. Sprague Fund, 1924.671

Psalter (MS Ludwig VIII 2)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Würzburg was the site of an active workshop of professional illuminators around the middle of the thirteenth century. Working for monasteries and nobility, Christians and Jews, these lay painters were familiar with slightly earlier, aristocratic works like the “Arenberg Psalter.” Although the intended recipient of this deluxe book of Psalms remains unknown, it counts among the earliest and most lavish products of the workshop. Featuring the opening words of Psalm 1 spread across two pages, the double frontispiece begins with a large letter B at left, in which Christ sits enthroned above a seated King David, who is flanked by musicians. Unusually, the facing page presents the remaining letters in a golden grid, enhancing the sacred text.

Psalter, in Latin

Germany, Würzburg, ca. 1240–50

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS Ludwig VIII 2, fols. 11v–12r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

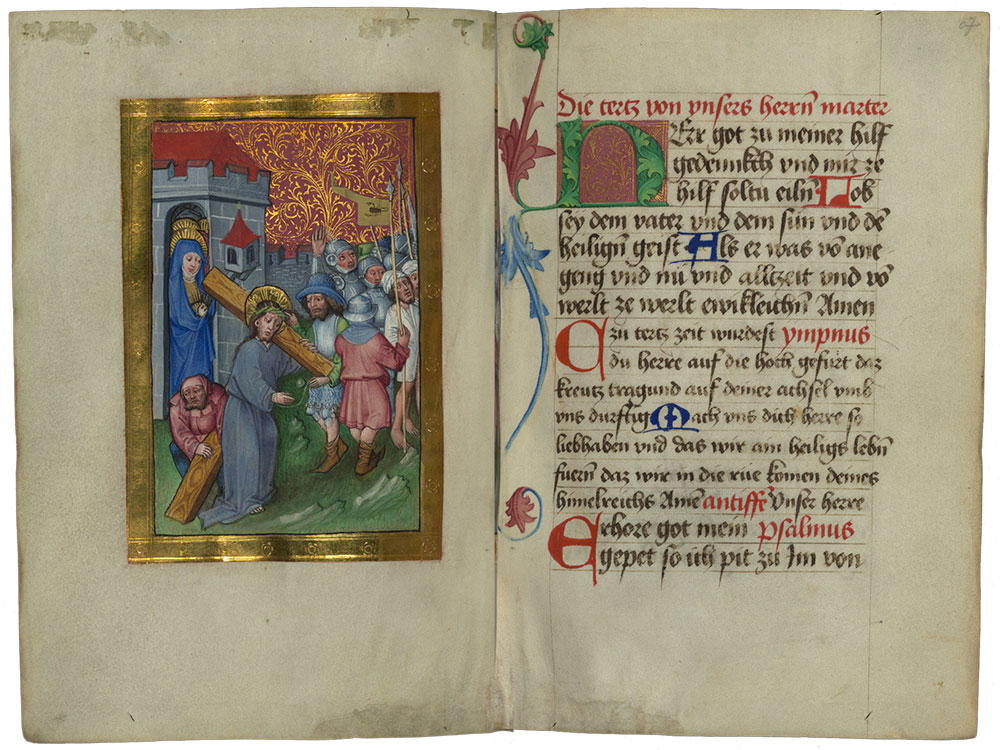

Prayer Book (MS M.739)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

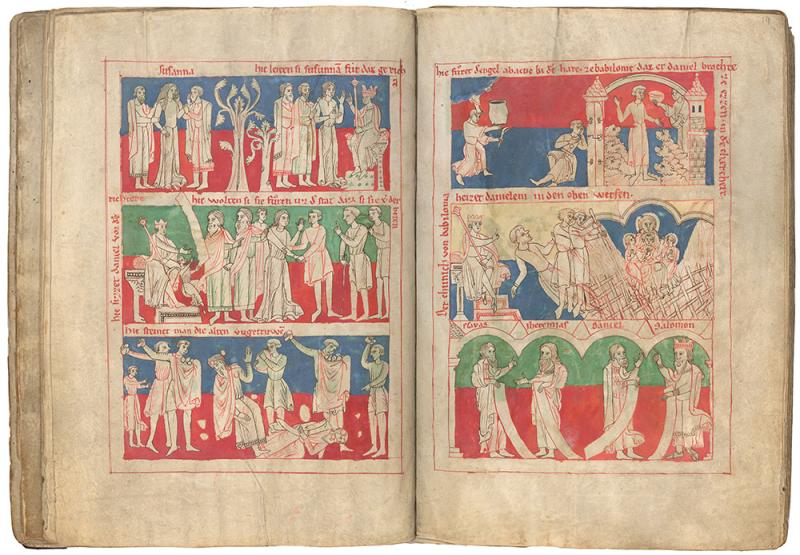

This prayer book, which conceivably belonged to St. Hedwig, features a vast prefatory cycle of approximately 160 Old and New Testament scenes, framed by inscriptions in German. These narrative scenes are depicted in unusually elaborate detail. The story of Susannah and the Elders, for example, begins at upper left with the heroine physically accosted by two older men, then falsely accused of adultery before a judge. Below, a young Daniel intercedes on her behalf, interrogating the elders. Finally, as punishment for their false witness, the men are stoned to death. The story of Daniel continues on the facing page. This elaborate tale of virtue in the face of corruption may have had special appeal to the book’s first, female owner.

Prayer Book (Cursus sanctae Mariae virginis), in Latin and German

Germany, Bamberg (?), ca. 1204–19

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.739, fols. 18v–19r

Purchased, 1928

Hedwig Codex

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

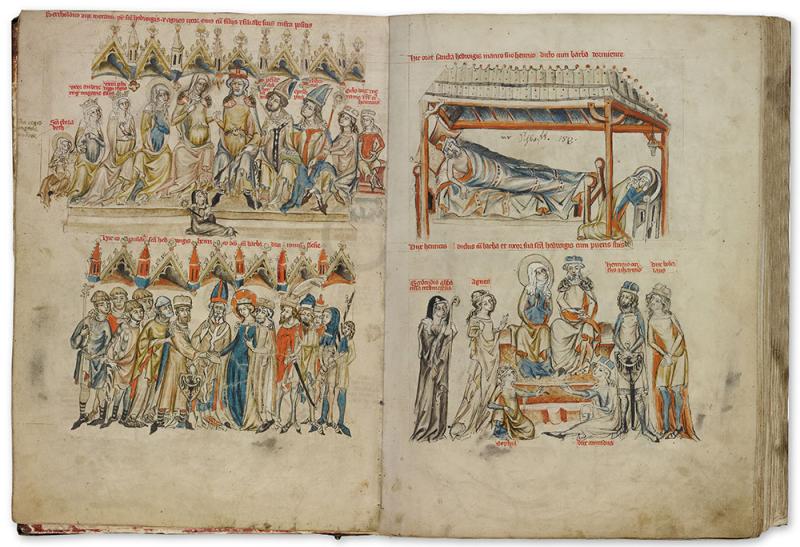

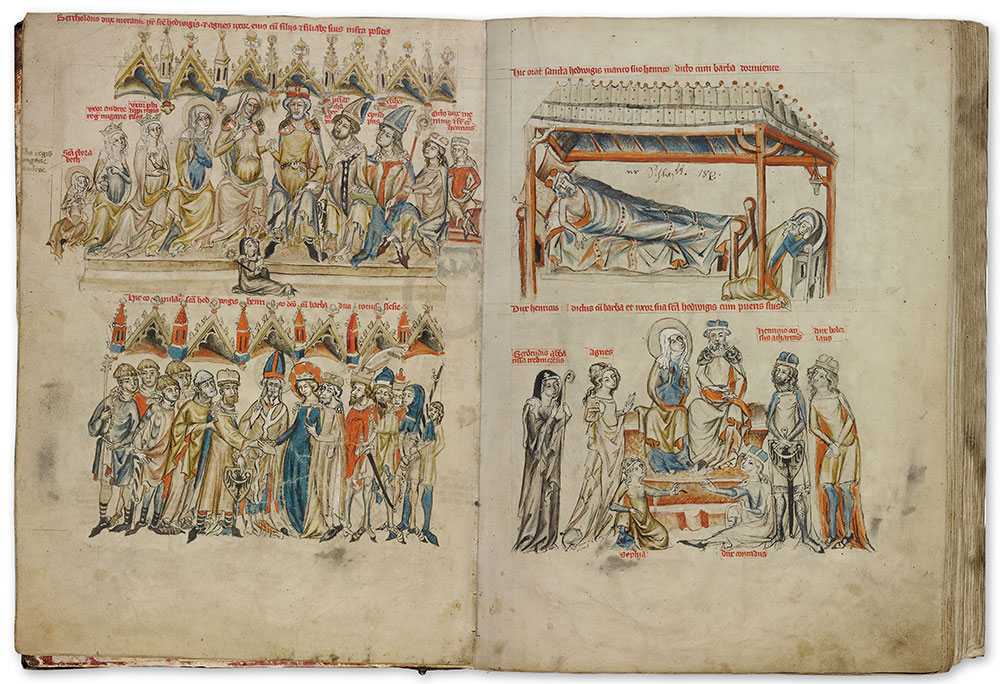

In 1203, Duke Henry I of Silesia (d. 1238), from the Piast dynasty, and his wife, Hedwig of Andechs (d. 1243), founded the Cistercian convent of Trebnitz (Trzebnica). Hedwig would retire there as a widow. For centuries thereafter, all the convent’s abbesses were princesses of the Piast dynasty. This manuscript reproduces the dossier in support of Hedwig’s canonization, which occurred in 1267. Depicting episodes from her life and tracing her family history, its drawings provide emblematic images of aristocratic piety and of female piety in particular. At left is the family of Hedwig’s father, Berthold IV of Andechs, and, below, the union of Hedwig and Henry I, who, following the birth of their children, had a chaste marriage. The first scene on the facing page depicts Hedwig praying while her husband sleeps. The scene below depicts the couple with their children.

"Hedwig Codex," in Latin

Written by Nicolaus of Prussia for Duke Ludwig I of Liegnitz and Brieg

Poland (Silesia), 1353

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MSMS Ludwig XI 7, fols. 10v–11r

Purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1983

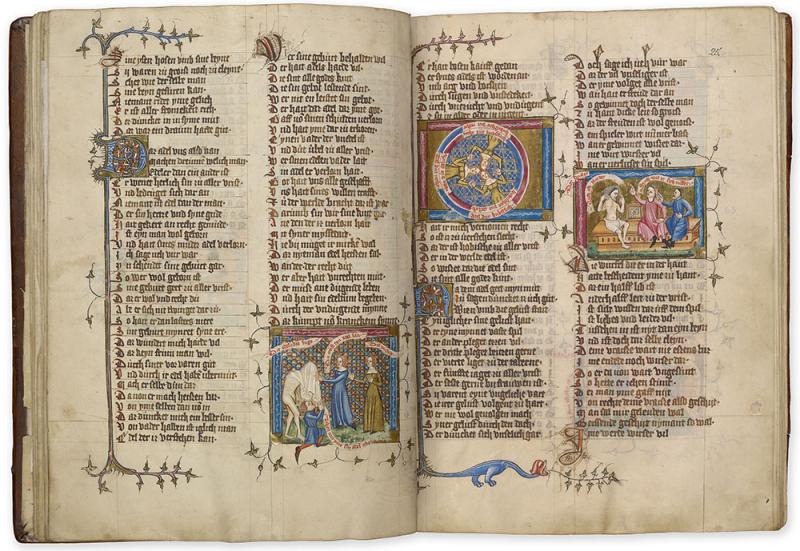

Der wälsche Gast (The Italian Guest)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

Written around 1215–16, The Italian Guest is the sole surviving poem by Thomasin von Zerclaere, a canon at the court of the German-speaking patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli (northern Italy). The work seeks to educate noblemen in the rules and norms of courtly love, chivalry, ethics, rulership, and good manners. The illustrations constitute a critical part of the work’s didactic program and enhanced its appeal to lay readers. At left, personifications of vices rob a nobleman of his clothing. At right, Justice, Nobility, and Courtliness join hands in a circle; a second miniature shows the winners and loser of backgammon, a critique of gambling. This copy was commissioned by Kuno von Falkenstein (1320–1388), archbishop elector of the imperial city of Trier.

Thomasin von Zerclaere

Der wälsche Gast (The Italian Guest), in German

Germany, Trier, ca. 1380

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.54, fols. 24v–25r

Gift of the Trustees of the William S. Glazier Collection, 1984

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

Aristocratic patronage made its mark on secular illustration, as exemplified by The Italian Guest, a didactic poem written around 1215–16. The sole surviving work of Thomasin von Zerclaere a canon at the court of the German-speaking patriarch of Aquileia in Friuli at the northern end of the Adriatic Sea, it seeks to educate noblemen in the rules and norms of courtly love, chivalry, ethics, rulership, and what we would call good manners. The poem reflects the perceived need to lend the court, which by the thirteenth century had emerged as a cultural center independent of ecclesiastical control, its own ethical rationale. The illustrations, which comprise as many as 125 separate subjects, constitute a critical part of the work’s didactic program and certainly enhanced its appeal to lay readers. This fourteenth-century copy of the work made for Kuno von Falkenstein, the archbishop-elector of the Free Imperial City of Trier, speaks to its crossover appeal to both clerical and aristocratic audiences.

The three miniatures on this opening, indebted in style to contemporary French illumination, focus on the Virtues and Vices. Rather than prefacing sections of the text, the images have been inserted directly into the relevant passages of the narrative, enhancing their immediacy.

The first, on the verso, shows a nobleman robbed of his clothing by personifications of the vices, literally stripping him of his nobility. Kneeling below the unfortunate noble is a personification of Wickedness; to the right stand two women exemplifying Deceit and Inconstancy.

Two miniatures on the facing page represent, respectively, the affinity among Justice, Nobility, and Courtliness—expressed by means of their joining hands in a circle—and, in a scene reminiscent of later genre paintings, the winners and loser of a board game, in this case backgammon, a critique of gambling. Whereas the loser has lost even his clothes and bewails his blindness, his opponents exclaim, “See how he cries out!” Harking back to famous literary heroes, Thomasin asks: “Where are Erec and Gawain, where are Parzival and Iwein? . . . The virtuous people are all hidden away.”

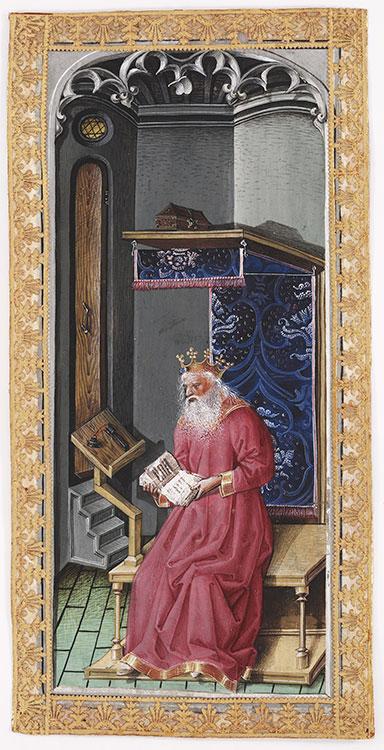

Weltchronik (World Chronicle)

ARISTOCRATIC PATRONAGE

The 243 illustrations in this copy of Henry of Munich’s World Chronicle entertained and edified aristocratic readers. As part of the work’s expansive paraphrase of Jewish scripture in German verse, one miniature shows King David battling the Philistines; the other shows David playing his harp and followed by trumpeters, leading the ark of the covenant back to Jerusalem. When the oxen hauling the ark stumbled, Uzzah, the son of Abinadab, sought to steady it with his hand, in violation of the law, and was immediately struck down, as seen at the center. The oblong formats spanning both text columns lend the images narrative thrust. While depicting distant historical events, the lively miniatures would have evoked contemporary military customs and courtly pageantry for the manuscript’s readers.

Henry of Munich

Weltchronik (World Chronicle), in German

Germany, Regensburg, ca. 1360

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.769, fols. 181v–182r

Purchased, 1931

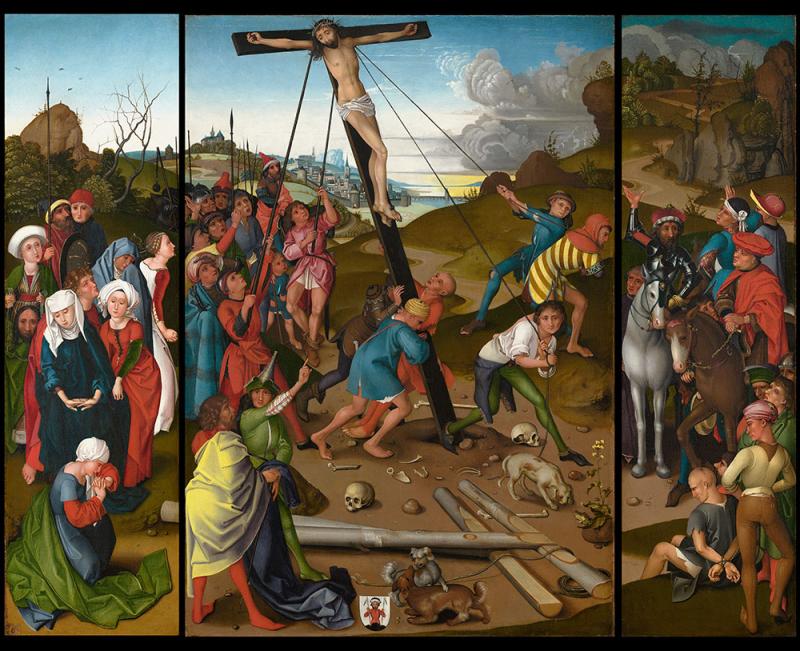

Imperial Cities

15th–16th Century

The term “free imperial city” (Reichsstadt) was coined in the fifteenth century, but the concept had roots extending back for centuries. Such cities were free from any territorial lord, secular or religious. They answered only to the emperor, who in turn granted the cities special privileges such as the right to mint coins, organize militias, and, most importantly, collect taxes and hold market fairs. Tied to vast commercial networks, these fairs enabled cities like Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Mainz to become hubs for skilled artisans, who produced luxury goods including books, both printed and handwritten. The development of these cities led to profound changes in patterns of artistic patronage, particularly when it came to making works for the open market. Imperial cities proudly proclaimed their status through a variety of visual media, from seals to public monuments. Their wealthy families competed with one another for attention in civic and religious arenas, all of which spurred artistic innovation and rivalry. Commerce and creativity went hand in hand.

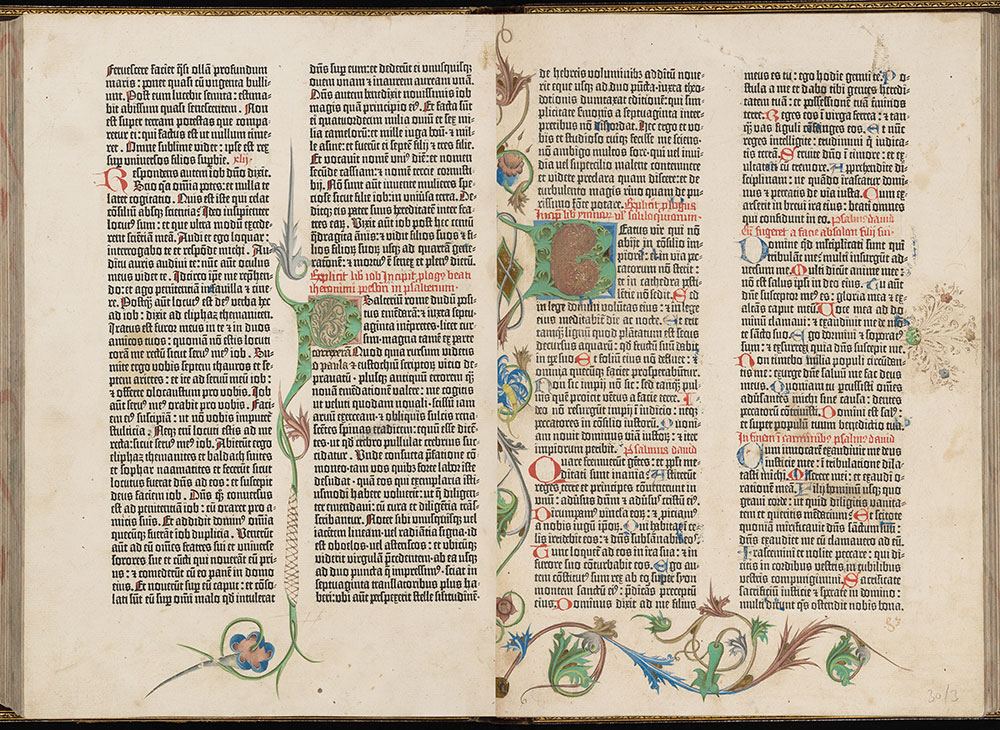

Bible of Andreas of Austria

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL

Named after its scribe, Andreas, this Bible was illuminated by four artists, a complex collaboration typical of court production in Prague during the reign of Emperor Wenceslas IV (r. 1376–1400). Its intended recipient was likely the scribe’s benefactor, William of Hasenburg (d. 1393), who had close ties to court and to the August-inian monastery at Roudnice nad Laben, the country seat of Prague’s archbishops. Marking the beginning of Genesis, the large initial I comprises seven medallions depicting Creation. The uppermost conflates the first and fourth days: the separation of light and dark and the creation of the sun, moon, and stars. The second roundel shows Earth, at center, surrounded by bands representing water and air. Together, the two medallions refer in schematic fashion to the cosmological system devised by Ptolemy (ca. 100–170), whose works were familiar at the court of Wenceslas due to the monarch’s obsessive interest in astrology.

"Bible of Andreas of Austria," in Latin

Written by Andreas of Austria for William of Hasenburg (d. 1393)

Czech Republic (Bohemia), Prague or Roudnice nad Laben, 1391

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.833, fols. 4v–5r

Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund, 1950

Jeffrey Hamburger, Kuno Francke Professor of German Art & Literature, Harvard University

The flourishing court culture at Prague attracted scholars and craftsmen from all corners of the Empire. One such scribe, Andreas of Austria, names himself in the colophon he added to this giant bible, dated 1391.

Although Andreas did not write the entire bible himself, his having taken credit for the whole suggests that the volume was his gift to a patron. That patron may well have been William of Hasenburg, father of a future archbishop of Prague, who may have had ties to the nearby Augustinian monastery at Roudnice nad Labem, a country seat for the archbishops where the bible may have been made.

The large initial I for Genesis belongs to a type coined in the late eleventh century. Occupying six vertically disposed medallions (one for each day of Creation),the Hexameron towers above the figure of Christ-Logos enthroned among angels, resting on the seventh day. Such scenes of Creation usually run from bottom to top, like a stained-glass window, with God crowning the image. Here, however, the direction has been reversed.

Such Genesis initials offered opportunities for cosmological speculation. The uppermost medallion conflates the first and fourth days: the separation of light and dark and the creation of the sun, moon, and stars. Against a celestial background filled with angels, the Christ-Logos blesses a celestial orb on whose circumference sit the sun and moon. The sphere below, split into quadrants by large cracks, represents the four elements. In the second medallion, the Earth is surrounded by offset circles of water and air. Together, the two medallions refer in schematic fashion to the system devised by Ptolemy, whose works were familiar at the court of Emperor Wenceslas on account of his obsessive interest in astrology.

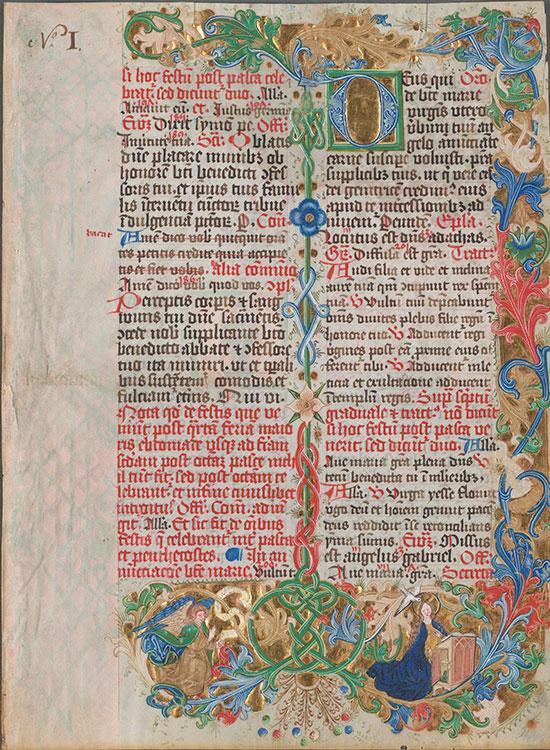

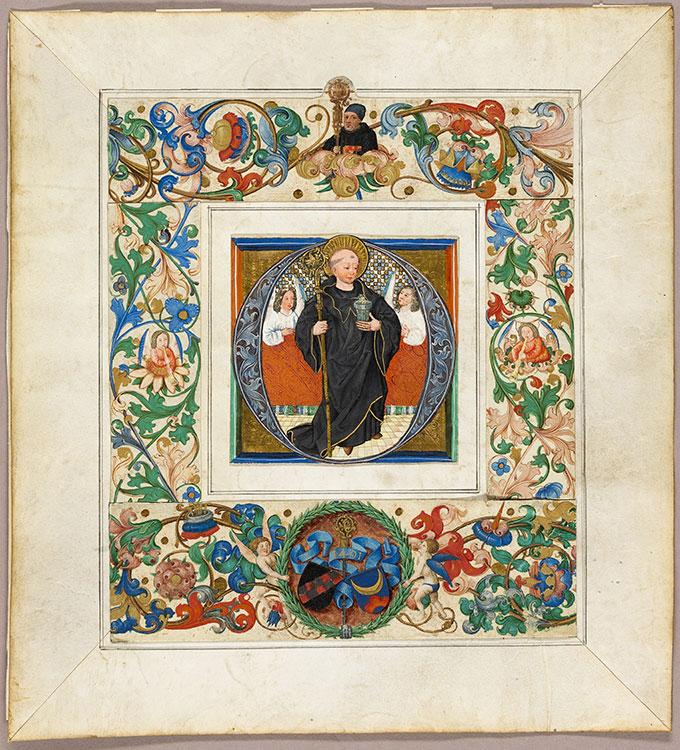

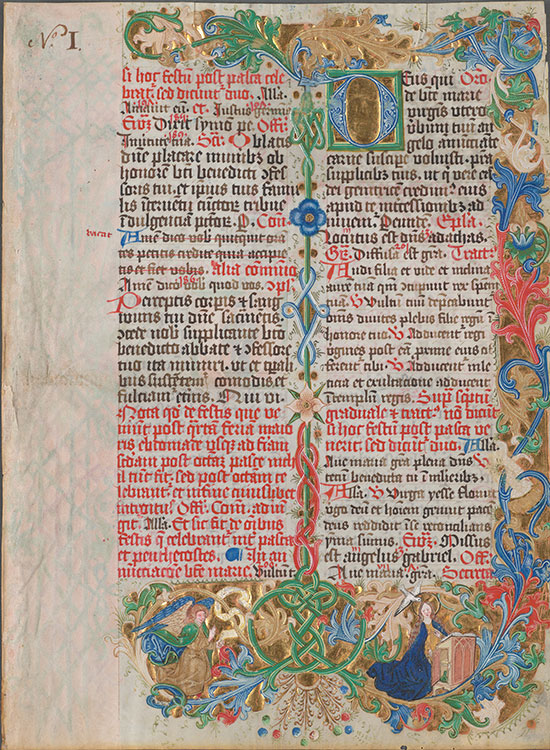

Leaf from the Seitenstetten Antiphonary

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL

This leaf from a dismembered choir book exemplifies the “Beautiful Style” in Prague, associated with the court of Emperor Wenceslas IV. The initial for Christmas depicts the Virgin Mary kneeling before the Christ Child, surrounded by a mandorla of light. Both details relate to a vision of Christ’s birth experienced by St. Birgitta of Sweden (1303–1373). In the margin, a Benedictine monk imitates the Virgin’s pose, holding a scroll that reads “Pray for us to God.” The manuscript was likely part of a set donated to a Benedictine monastery by an unidentified patron, who must have come from the highest echelons of the court. His orange garments as depicted within another initial from the book (shown below) indicate that he was not a cleric.

Leaf from the “Seitenstetten Antiphonary,” in Latin

Czech Republic (Bohemia), Prague, ca. 1405

Cleveland Museum of Art

Andrew R. And Martha Holden Jennings Fund, 1976.100

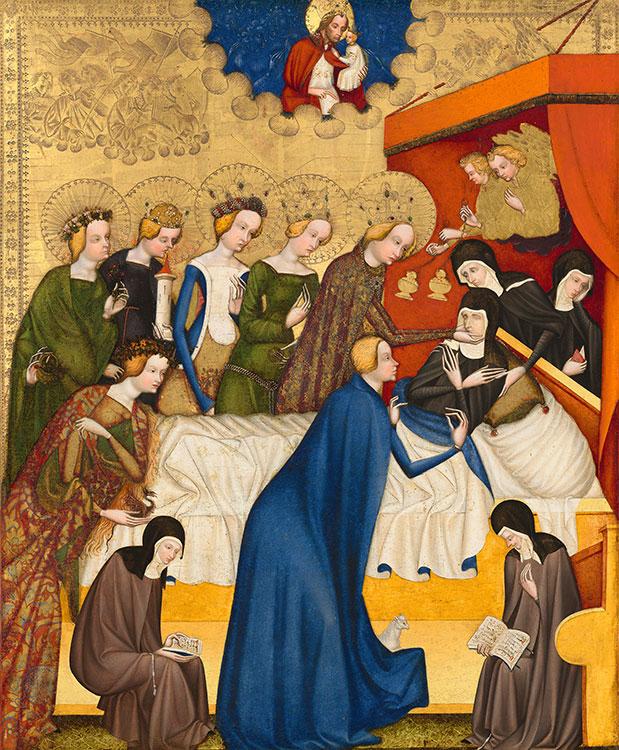

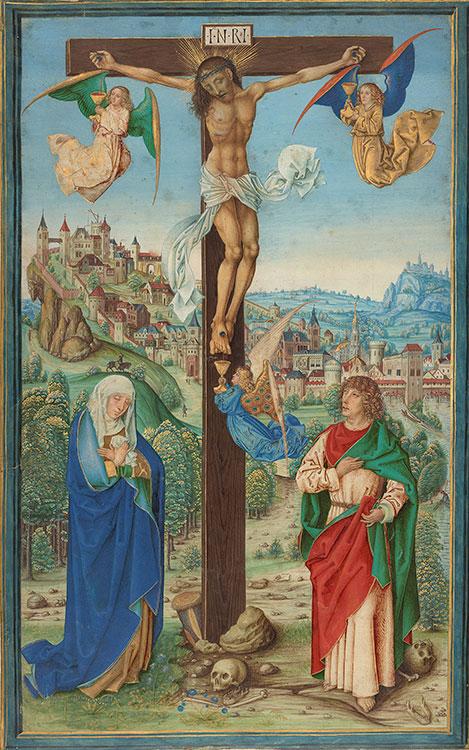

Adoration of the Magi and Dormition of the Virgin

PRAGUE: A NEW CAPITAL