Poetry & Patronage: The Laubespine-Villeroy Library Rediscovered

Young, handsome, and highborn, the French courtier Claude III de Laubespine (1545–1570) lived in luxury after marrying an heiress and obtaining the favor of King Charles IX. He became a secretary of state and rose high enough in the royal entourage to be entrusted with diplomatic missions abroad. The poets Pierre de Ronsard and Philippe Desportes, seeking patronage from Claude III’s family, composed elegant tributes in verse praising him; his father, Claude II; his sister, Madeleine; and her husband, Nicolas de Villeroy, who was also a secretary of state. Claude III’s brilliant career at court was cut short when he died at the age of twenty-five. He left a splendid library, which was dispersed after passing through the hands of his sister and brother-in-law; only recently have his books been identified and properly appreciated for their superb quality and fine bindings. Laubespine now ranks among the great collectors of the French Renaissance. For the first time since his death 450 years ago, this exhibition brings together some of the most spectacular bindings in his collection, exquisite examples of Renaissance ornamental design attesting to a noble statesman’s knowledge, wealth, and taste.

Poetry and Patronage: The Laubespine-Villeroy Library Rediscovered is made possible by T. Kimball Brooker, with assistance from Roland and Mary Ann Folter; Jamie Kleinberg Kamph, Stonehouse Bindery; Jonathan and Megumi Hill; Martha J. Fleischman; and Professor and Mrs. Eugene S. Flamm.

Overview

Gallery Images

Workshop of François Clouet

Charles IX (1550−1574) was nine years old when he became king of France. In this picture he is not that much older. His mother, Catherine de’ Medici, acted as regent with the assistance of her advisors, including several members of the Laubespine family. Secretary of State Claude II de Laubespine (1510− 1567), Claude III’s father, helped the king and his mother formulate foreign policy and cope with domestic disturbances during the Wars of Religion. He was amply rewarded for his service to the crown and was able to prepare his son for a similar political career. Born and bred for high office, Claude III became one of the king’s closest confidants.

Workshop of François Clouet (d. 1572)

Charles IX, King of France, ca. 1561−64

Oil on wood

Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931; 32.100.124

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Attributed to Pierre Dumonstier the Elder

The widow of one king and mother of three others, Catherine de’ Medici (1519–1589) was one of the most powerful women in Europe. She ruled France during the minority of Charles IX and continued to have a voice in affairs of state after he came of age.She had the unenviable task of trying to reconcilethe Catholic and Protestant factions during the Warsof Religion, although she ultimately abandoned herattempts at compromise and bears some responsibilityfor the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. During these times of crisis, she relied on the advice of twoLaubespine brothers: Sébastien, an ambassador posted in several countries, and Claude II, secretaryof state. She thought so highly of Claude II that shevisited him the day before he died to confer about military operations against the Protestants.

Attributed to Pierre Dumonstier the Elder

(ca. 1545–1625), after François Clouet (d. 1572)

Catherine de’ Medici, Wife of Henry II, King

of France, ca. 1570–80

Black chalk, with red and yellow chalk, and some stumping, on cream paper

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1907; III, 65c

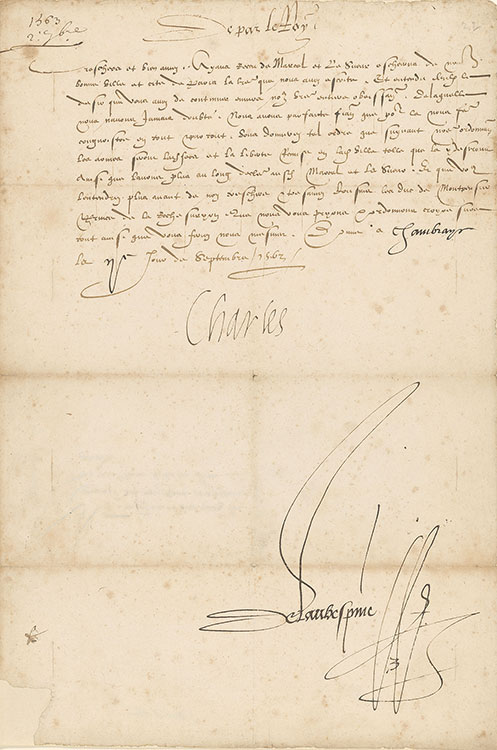

Charles IX

Here is a typical document countersigned by Claude II de Laubespine, an attempt to enforce gun control in Paris. King Charles IX had attained his majority just a few weeks before, and this was one of his first official acts. He instructs the aldermen to gather up firearms and deposit them in the Hôtel de Ville for safekeeping. No one was to be seen on the street carrying a pistol, dagger, or harquebus. Although the aldermen tried to maintain law and order, gangs roamed the city at night singing psalms and brandishing their weapons. This is one of several royal documents in the Morgan collection signed by or addressed to members of the Laubespine family.

Charles IX, King of France (1550−1574)

Letter to Claude Marcel and Jehan Le Sueur,

2 September 1563, countersigned by Claude II

de Laubespine

The Morgan Library & Museum; MA unassigned

Saint Albertus Magnus

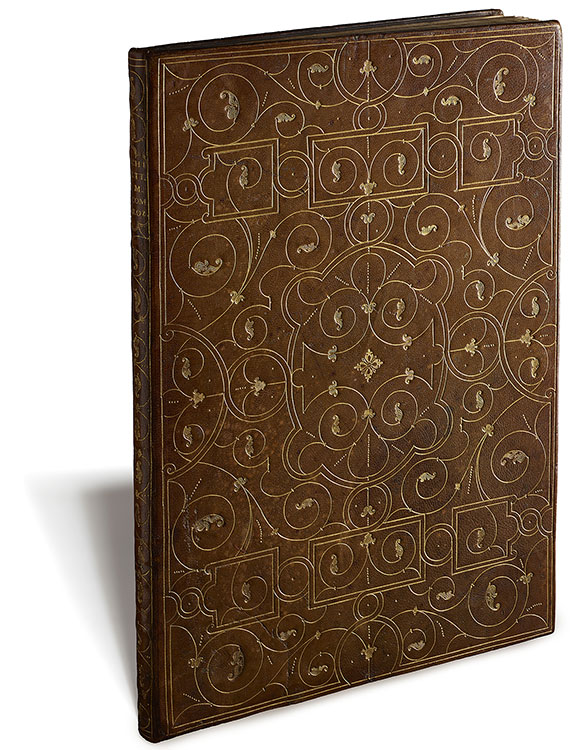

Jean Grolier (1489/90–1565) was the most prominent patron of fine binding in France during the Renaissance. This binding displays his characteristic motto: Io. Gr. Et Amicorum (For use by Jean Grolier and his friends). A treasurer of France, rich enough to build two substantial libraries, Grolier would have been a model for Claude III de Laubespine. Like Grolier, Laubespine made a fortune in government service and built a library remarkable for the quality of its bindings. Both collectors patronized the Mahieu Aesop Binder workshop, which produced this binding circa 1560. Unlike Grolier, however, Laubespine left no marks of ownership—one of the reasons why his achievements remained unrecognized until now.

Saint Albertus Magnus

(1193?−1280)

Postillatio in Apocalypsim (Commentary on the Book of Revelation)

Basel: Jacob von Pfortzheim, 1506

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased in 1912; PML 19351

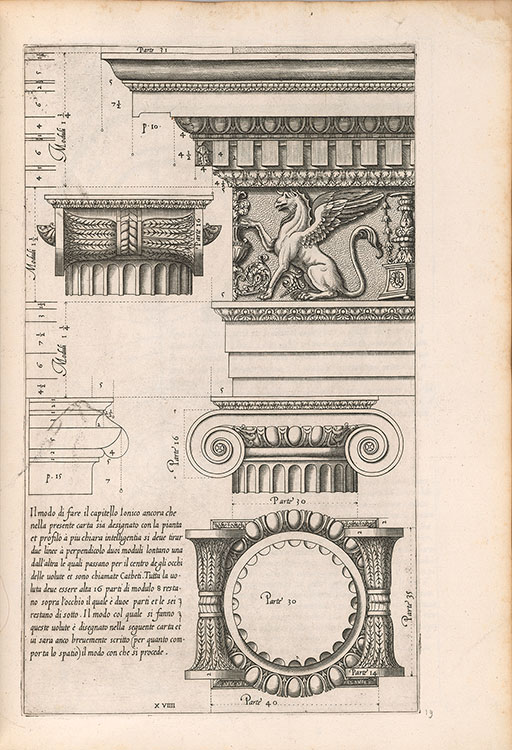

Sebastiano Serlio

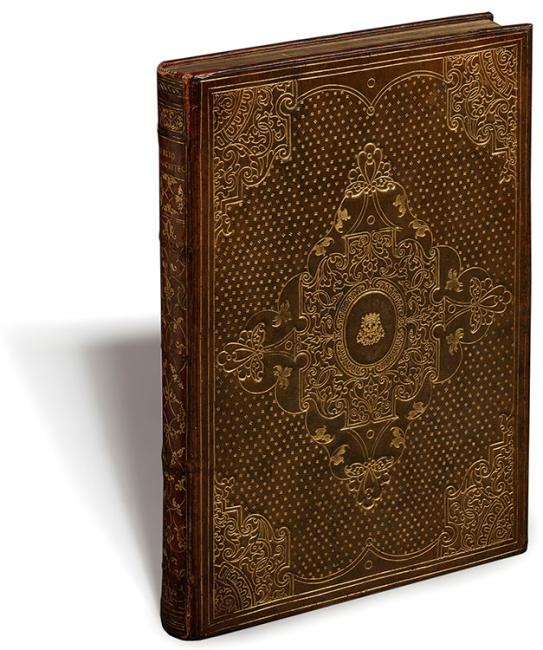

Claude III de Laubespine had a predilection for Italian imprints and books of architecture. The center-and-cornerpiece gilt-blocked design of this binding is also an Italian import, a style practiced in Venice and then adopted in Paris by Grolier’s Last Binder, among

others. Grolier commissioned at least twenty-three bindings from this workshop, and Laubespine carried on with about forty. After his library was dispersed, this binding passed through the hands of at least five eminent collectors. The list begins with the statesman and art patron Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) and Charles Henry, Count Hoym (1694–1736), whose gilt cipher was inserted in the center cartouche in the early eighteenth century.

Sebastiano Serlio (1475−1554)

Libro primo [–quinto] d’architettura (First [–Fifth] Book of Architecture)

Venice: Giovanni Battista and Melchiorre Sessa, 1559–62

The Wormsely Library

Photography by Andrew Smart of A.C.Cooper Ltd, London.

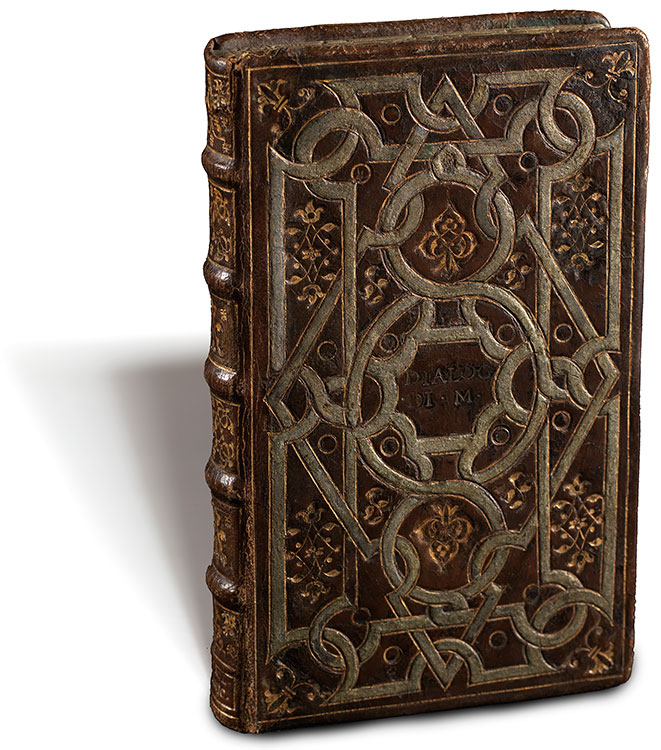

Sperone Speroni

This copy of Speroni’s Dialoghi is an excellent example of Laubespine’s interest in Italian literature. Quite possibly it first belonged to one of his elders, an ambassador to Venice who could have commissioned its painted strapwork binding after having returned to Paris in 1550. An ironic twist in its later history attests to the quality of the binding. Sometime before 1883, an unscrupulous member of the book trade deemed it good enough to be a Grolier binding and “improved” it by tooling the Grolier motto on the spine. It was identified as a fake Grolier in the 1950s, but the binding itself is authentic—and the inventory number makes it genuine insofar as its Laubespine-Villeroy provenance.

Sperone Speroni (1500−1588)

Dialoghi (Dialogues)

Venice: Sons of Aldus Manutius, 1546

Barbier-Mueller Foundation for the Study of Italian Renaissance Poetry (University of Geneva) / e-codices - Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland

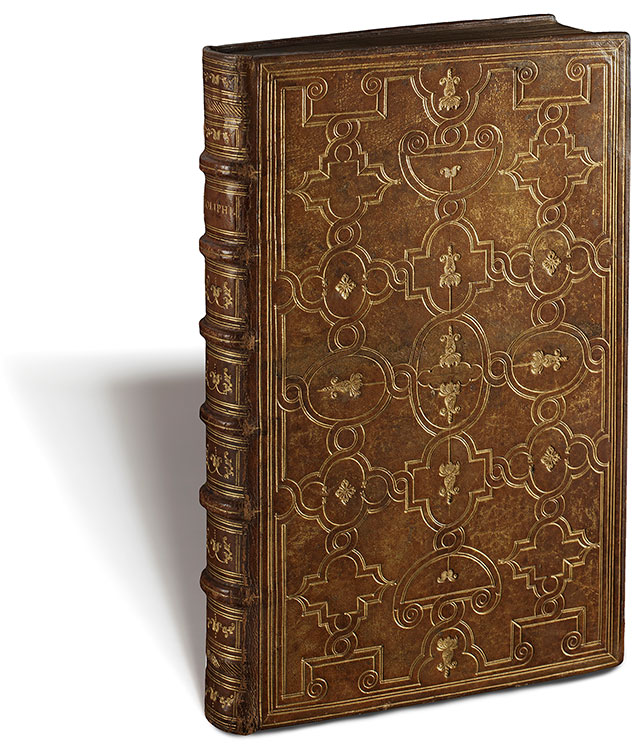

Jacopo Vignola

The bookbinding scholars Isabelle de Conihout and Pascal Ract- Madoux reconstructed the Laubespine-Villeroy library in a tour de force of hands-on historical research. They identified the books on the basis of inventory numbers inscribed on the flyleaves in brown ink (hence the term cote brune). Until then curators and collectors had struggled to explain these magnificent and mysterious bindings. Former Morgan director Frederick Adams declared that this elegant example “sends a tingle of pleasure down the spine” but regretted that he could not name the original owner. Now Claude III de Laubespine can be credited with commissioning the binding, executed in Paris circa 1567–68 by the Atelier au Vase.

Jacopo Vignola (1507−1573)

Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura (Rules of the

Five Orders of Architecture)

[Rome: s.n., 1562–64]

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased in 1960; PML 51314

Jacopo Vignola

The Italian architect Jacopo Vignola was famous in France and even worked there for several years to cast replica classical statues for the royal gardens in Fontainebleau. After returning to Italy, he won the patronage of the powerful Farnese family and Pope Julius III, for whom he built the Villa Giulia (one of the models for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library). Dedicated to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, Vignola’s Five Orders consolidated his reputation throughout Europe, where it went through dozens of editions. If not so opulent in its binding, the Morgan’s second copy of this definitive textbook shows what Laubespine looked for in his collection of architectural treatises.

Jacopo Vignola (1507−1573)

Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura (Rules of the Five Orders of Architecture)

[Rome: s.n., 1563]

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Henry S. Morgan, 1965; PML 55623

Vitruvius Pollio

This is the definitive Italian translation of Vitruvius Pollio’s De architectura, an essential text for Renaissance architects intent on emulating the buildings of classical antiquity. The patrician humanist Daniele Barbaro translated the text with the assistance of the renowned architect Andrea Palladio, who designed most of the woodcut illustrations. Together they could draw on philological erudition, archaeological expertise, and practical know-how to make sense of Vitruvius’s notoriously difficult Latin. Unlike his predecessors, Palladio sometimes provided three views of a building: a floor plan, an elevation, and a cross section. Barbaro presented this copy to the Croatian Hungarian humanist András Dudith.

Vitruvius Pollio (act. First century BCE)

I dieci libri dell’architettura (On the Art of Building in Ten Books)

Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1556

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Paul Mellon, 1979; PML 76348

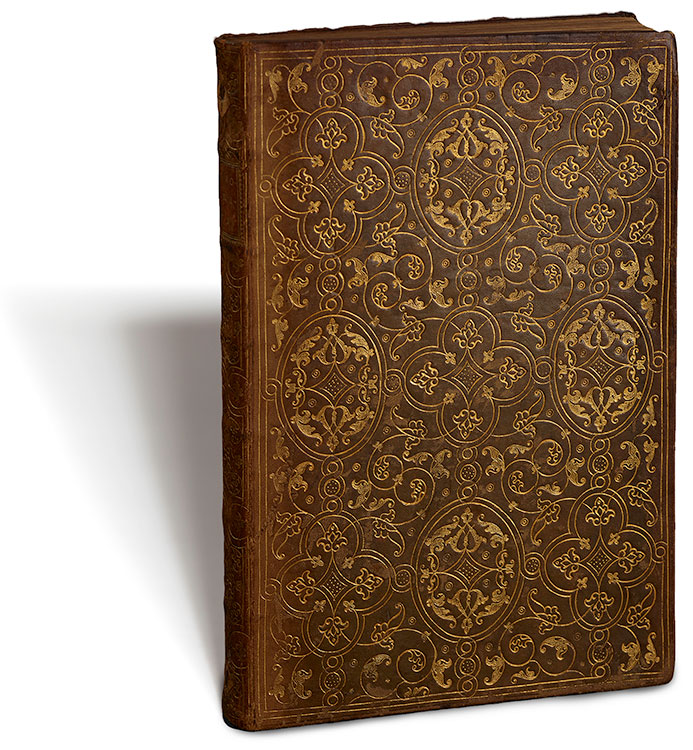

Vitruvius Pollio

Also executed by the Atelier au Vase, also covering an architectural treatise, this “primitive” fanfare binding is a twin of the Vignola binding in the adjoining case. The characteristic features of the fanfare style are gilt-tooled compartments of various shapes and sizes delineated by single and double fillets and filled with small floral ornaments. A larger oval compartment is usually at the center of the composition, which fully covers the boards. The classic fanfares of the 1570s were preceded by “primitive” and “empty” fanfares that emerged in the late 1560s. Claude III owned at least thirty bindings produced by the Atelier au Vase in these early iterations of the fanfare style.

Vitruvius Pollio (act. First century BCE)

I dieci libri dell’architettura (On the Art of Building in Ten Books)

Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1556

T. Kimball Brooker

Photography by Pixel Acuity

Francesco Colonna

Similar in concept to the “primitive” fanfare bindings in the center cases, this “empty” fanfare binding has minimal decoration in the gilt compartments. It too was executed by the Atelier au Vase, but the workshop sought to make it even more luxurious by treating the leather with powdered gold. This additional distinction reflected the importance of the Hypnerotomachia, already recognized in the Renaissance as one of the greatest illustrated books of all time. For Laubespine, an Italianist and a bibliophile, there could be no better way to express his collecting ambitions than to have this typographic masterpiece in a suitably sumptuous binding. He would have appreciated it all the more for its architectural illustrations.

Francesco Colonna (d. 1527)

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Venice: Aldus Manutius [for Leonardus Crassus], December 1499

Collection of Jean Bonna / e-codices - Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland

Francesco Colonna

The tongue-twisting title of this book can be translated as The Strife of Love in a Dream by the Lover of Polia. The intricate construction of the dream narrative and the text’s strange medley of languages sometimes taxed readers’ patience, but the elegant typography and magnificent woodcuts compensated for those difficulties. Usually attributed to the Paduan miniaturist Benedetto Bordon, the illustrations made the fame of the Hypnerotomachia in Italy and France. Grolier had as many as five copies of the first edition, including one bound for him by the royal binder Gommar Estienne (now in the collection of T. Kimball Brooker). Laubespine probably also owned a copy of the 1545 second edition.

Francesco Colonna (d. 1527)

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Venice: Aldus Manutius [for Leonardus Crassus], December 1499

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased With the Irwin Collection, 1900; PML 373

Philippe Desportes

The luxurious Hypnerotomachia bound for Claude III later passed to his sister, Madeleine. It probably influenced a neo-Latin poem she wrote in praise of Chanteloup, a garden famous in its day for features inspired by Greek and Latin myths. The garden belonged to her husband’s cousin, a connection that enabled the art historian Matthieu Dejean to attribute the poem to Madeleine. The only work published under her name in her lifetime is this commendatory sonnet addressed to Philippe Desportes, signed CMDL (Callianthe-Madeleine-de-Laubespine). The pseudonym Callianthe is derived from the Greek for “beautiful flower” and plays on her family name, aubépine, a tree with white flowers.

Philippe Desportes (1546−1606)

Les premieres oevvres de Philippes Des Portes (The First Works of Philippe Desportes)

Paris: Mamert Patisson for Robert Estienne, 1583

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased With the De Forest Collection, 1899; PML 2301

Xenophon

These too are “empty” fanfare bindings produced by the Atelier au Vase. Laubespine commissioned them for this two-volume edition of the Greek historian Xenophon, a masterwork of the scholarprinter Henri II Estienne, who collated the text himself and

printed it with the famous Greek types cut by Claude Garamond. Both volumes could be obtained separately should one prefer to have Xenophon only in Greek or only in Latin. They were shelved separately in the Laubespine-Villeroy library and parted ways after it was dispersed—but they were reunited by the Wormsley Library, which acquired first the Greek text and then the Latin text in 2006 when, by a stroke of luck, it came up for sale at auction.

Xenophon (ca. 428/27–ca. 354 BCE)

Omnia quae extant opera (Complete Works), 2 vols.

Geneva: Henri II Estienne, 1561

The Wormsely Library

Photography by Andrew Smart of A.C.Cooper Ltd, London

Prudentius

The early fifth-century Christian poet Prudentius was highly esteemed in the Renaissance. This pocket-size edition of his works may have had a place in the Laubespine library; as yet, the evidence is not entirely clear. The binding is certainly an excellent example of the “primitive” fanfare style favored by Laubespine, whose Vignola—displayed at the beginning of this exhibition—replicates the decorative scheme almost exactly, only several sizes larger. The Atelier au Vase must have produced this binding as well. Furthermore, there is a twin binding on a closely related work, a 1563 Seneca issued in the same format by the same publisher, which is just the sort of pairing Laubespine would have liked.

Prudentius (348–ca. 410 CE)

Opera (Complete Works)

Edited by Victor Giselin

Paris: Hiérosme de Marnef, 1562

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased With the Toovey Collection, 1899; PML 1103

Commesso pendant

A Renaissance library could include a cabinet of curiosities stocked with coins, cameos, statuettes, and gemstones. Like fine bindings, these curios could be tokens of wealth and knowledge. Collectors might puzzle over the meaning of carved gemstones just as they might elucidate allegories in medallion vignettes stamped on bindings. Here, the cardinal virtue Prudence holds two of her symbolic attributes, a serpent and a mirror, by which she heeds the aphorism “Know thyself.” Jewels figure in the estate inventory of Laubespine’s sister, Madeleine de Villeroy, a gifted poet who knew how to decipher emblems like Prudence.

Prudence

Commesso pendant, ca. 1550−60

Chalcedony, mounted in gold with enamel, rubies, emeralds, diamond, and pearl

Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917; 17.190.907, 17.190.907 (Mount)

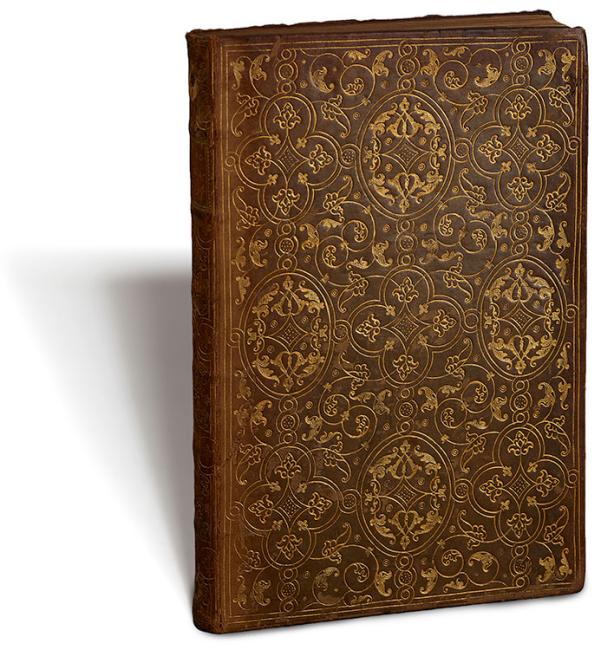

Pierre Galland

The Mahieu Aesop Binder workshop gets its name from the binding on a 1501 edition of Aesop’s Fables made for Thomas Mahieu (act. Ca. 1547–ca. 1580), a collector akin to Grolier in his taste and technique. Mahieu was also a treasurer of France, and he used a similar motto on his bindings. This workshop produced at least fifteen bindings for him, four for Grolier, and nineteen for Claude III de Laubespine. The binding displayed here covers a collection of early Roman treatises on land surveying, edited by the rhetorician Pierre Galland and the printer Adrien Turnèbe. In his introduction, Galland says that he and Turnèbe ransacked monasteries for classical texts just as well-trained dogs track down wild beasts in thickets.

Pierre Galland (1510−1559)

De agrorum conditionibus & constitutionibus limitum (The Writings of the Roman Land Surveyors)

Paris: Adrien Turnèbe, 1554

T. Kimball Brooker

Photography by Pixel Acuity

Theocritus

Also bound in the Mahieu Aesop Binder workshop, this collection of poems by Theocritus is one of only nine Greek texts known to have been owned by Laubespine. If more comfortable with Latin than Greek, he still might have appreciated this volume because of its printer, the renowned Aldus Manutius, whose work is also represented

in this exhibition by the Hypnerotomachia PoliphiliAldus was an enterprising editor of classical texts and printed many of them for the first time—for example, some of Theocritus’s bucolic verse included here. Furthermore, this edition serves as a specimen of Aldus’s first Greek typeface, a typographic innovation no less influential than the roman font in the Hypnerotomachia.

Theocritus (ca. 300–after 260 BCE)

Idyllia [Greek]

Venice: Aldus Manutius, February 1495/96

T. Kimball Brooker

Photography by Pixel Acuity

Circle of Jean Decourt

Madeleine de Laubespine inherited her brother’s library after his death in 1570. It would have meant a lot to her, not just as a memorial of a favorite sibling but also as a store of literature that she could appreciate in its own right. Celebrated for her beauty and wit, Madeleine was an accomplished poet who left behind a substantial body of work, including sonnets, songs, and translations. She and other members of her family were patrons of poets such as Pierre de Ronsard and Philippe Desportes (who was also one of her lovers). In one poem, Desportes mourned the loss of Claude III and pledged himself to Madeleine “on the holy grave of someone I loved so much and can remember by his likeness so well conveyed in you.” Ronsard praised her verse, although he confessed, “I’m sad that your rising sun doth shine upon my muse abased below.”

Circle of Jean Decourt (ca. 1530–after 1585)

Portrait of Madeleine de Laubespine, dame de Villeroy, sixteenth century

Oil on panel

Collection of William Kopelman

Jean Bénard

The historian Jean Bénard dedicated this account of Anglo-French diplomatic relations to Nicolas de Villeroy, whose arms are painted beneath the dedicatory epistle. Another page displays the patron’s motto, Per ardua surgo (Through difficulties I arise), and his emblem, a tree growing on a mountaintop with sufficient strength to withstand the summer heat and winter storms. Other pages are illuminated with floral borders. Bénard recites French grievances against England, such as its capture of the port city of Calais and its alliances with other countries too close for comfort. As secretary of state, Villeroy helped to conduct his country’s foreign affairs and would have valued this historical overview.

Jean Bénard

Sommaires recueils des querelles et pretentions anciennes des Anglois contre les François (A History of Conflicts between England and France)

Illuminated manuscript, 1572

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan before 1913; MA 15

Pierre de Ronsard

In addition to the poem dedicated to Villeroy shown above and the sonnet in honor of Madeleine, Ronsard addressed an “Autumn Hymn” to Claude II de Laubespine and wrote a eulogy for Claude III de Laubespine. He depended on the family for his livelihood as a man of letters. A king could grant a pension to a favored poet, but court officials sometimes intervened to expedite the payment. They might also supplement the royal largesse with gifts of their own. All of Ronsard’s poems dedicated to the Laubespine family are present in this edition. A stately two-volume folio, it is an unusually ambitious publication with extensive commentaries and engraved portraits of notables who figure in the poetry.

Pierre de Ronsard (1524−1585)

Les oeuvres de Pierre de Ronsard, gentilhomme vandosmois (The Works of Pierre de Ronsard,

Gentleman of Vendôme)

Paris: Nicolas Buon, 1623

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Trustees of the Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection, 1977; Heineman 842

Pierre de Ronsard

The bindings scholar Pascal Ract-Madoux named the Ronsard Binder for this set of Pierre de Ronsard’s works. It is missing the last volume, which was already absent when the Conflans library inventory was compiled circa 1617, but it reaffirms the close connection between the poet and the Laubespine family. Revised by Ronsard himself, this 1567 collection of his works is one of the most important lifetime editions: it contains the definitive text of four seasonal hymns, each addressed to one of the four secretaries of state. The “Autumn Hymn” is dedicated to Claude II de Laubespine, who is also the subject of a sonnet that expresses perfectly the relationship between poet and patron: “I am the ship, you are my pilot: without you, sir, I cannot sail the seas.”

Pierre de Ronsard (1524−1585)

Les oeuvres de P. de Ronsard, gentilhomme vandomois (The Works of Pierre de Ronsard, Gentleman of Vendôme), 3 vols. In 4 parts

Paris: Gabriel Buon, 1567

Fondation Martin Bodmer

Bibliotheca Bodmeriana / e-codices - Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland