Title from ISTC.

Imprint from ISTC/GW.

Printed in type 1:140G. In 2 columns of 42 lines.

Collation: Vol. I: [A1] 1-9¹⁰ 10¹⁰(+8*: et aurum); [A2] 11-12¹⁰ 13⁶(+4*: noluerunt); [B1] 14-24¹⁰; [B2] 25¹⁰(+7*: eliasib) 26¹⁰(+9*: oriente); [B3] 27-32¹⁰ 33⁴: 324 leaves. Vol. II: [C1] 1-13¹⁰; [C2] 14-15¹⁰ 16¹⁰(+10*: In quo polluimus); [D1] 17-26¹⁰; [D2] 27¹²; [D3] 28¹⁰ (+7*: enim cristi); [D4] 29-30¹⁰ 31⁴(+3*: nobiscum); [D5] 32¹⁰: 319 leaves, leaves [32]/9-10 blank, + π4 (rubrication guide).

Paper format: Royal folio.

Sheets were seen by Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini some time before his letter of 12 March 1455 to Cardinal Juan de Carvajal, which was printed in Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, later Pius II, Pont. Max. Epistolae saeculares et pontificales. [Cologne : Arnold Ther Hoernen, ca. 1480; (ISTC ip00726500)], leaves p7v-q5v (with mention of the Bible on leaf q1 verso): see Meuthen 1982, and Davies 1996, pp. 193-201, with plate.

Copies at München BSB and Vienna ÖNB have a printed rubrication guide in four leaves, π4.

PML copy with unique third resetting: Setting A: I, [1]/2v and 9; I, [2 and 4]; I, [14]/1, 3-10; I, [15]; II, [1], Setting B: I, [1]/1, 3-8, and 10; I, [3]; I, [14]/2v; I, [16]; II, [2], and Setting C: I, [1]/2r; I, [5]/5.6; I, [14]/2r (see, Needham, "Paper Supply," 332-33).

PML copy leaf dimensions: 37.5 x 27 cm.

PML copy is Old Testament only, lacking 135 leaves: vol. II, [19]/9-[32]/10 and rubrication guide (π4).

42-line Bible

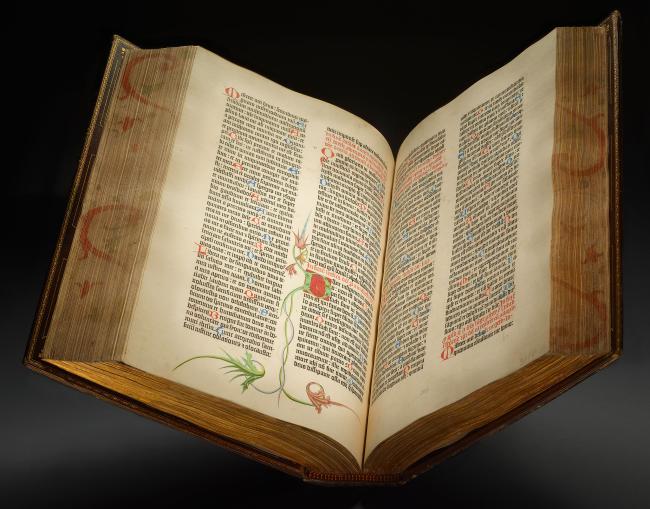

Hand decoration: Illuminated by the Fust Master, ca. 1462, with foliate initials and border decoration, alternating red and blue lombards, red headlines, rubrics, and capital strokes. Due to moisture damage and Matthews's rebinding, many of the painted decorations have offset onto facing leaves. Annotations: Compositor's marks from the Fust and Schoeffer press for setting the 1462 Bible, see Ikeda, "Two Gutenberg Bibles," PBSA 106 (2012): 357-72.

The invention of printing is commonly credited to Johann Gutenberg, who developed the technique of casting metal types and composing them letter by letter, line by line to produce pages ready for the press where they could be inked and printed on sheets of paper or vellum. To exploit this invention, he set up one workshop, or possibly two, in Mainz, Germany, and raised a considerable sum of money for the production of the Bible, which was completed around 1455. Bibliographers believe that Gutenberg and his successors printed between 120 and 135 copies of the Bible on paper and between 40 and 45 copies on vellum, of which nearly 50 copies survive though not all are in good condition. A complete copy contains the Latin Vulgate text of the Bible in 1,282 pages, usually bound in two stout volumes.

Each of the three copies at the Morgan has a special story to tell about the design and manufacture of this famous book. Their testimony is all the more valuable because scholars have had to base their conjectures about Gutenberg's business dealings and production methods on just a few tantalizing documents.

The Morgan's copy on paper is remarkably well preserved. Large and fresh, it is missing only two blank leaves and retains some untrimmed leaves that show the layout of the page as originally envisioned by the inventor. The copy on vellum is lavishly illuminated although some decorated initials and ornamental borders were at some point excised and replaced by nineteenth-century facsimiles (sufficiently cunning to have fooled more than one unwary scholar). A German artist, possibly in the Mainz area, started to work on this copy, which then passed into other hands and was embellished in a remarkably different style with elaborate gilt initials, acanthus motifs, and rich illuminated borders that have been attributed to a workshop in or near Bruges.

The Morgan's second paper copy contains only the Old Testament but could have been issued in that state to use leftover sheets at the end of the press run. It has twenty-two pages with unique typesettings, as if the printers had to compensate at the last minute for missing or incomplete sheets. This copy is a magnificent example of the work of the Fust Master, an illuminator who in the service of Johann Fust decorated a number of early Mainz imprints. Fust helped finance the Bible and took over the Bible-printing firm after Gutenberg could not pay his debts. The Fust Master appears to have understood the potential of printing technology and devised painting techniques also suitable for mass production. He employed the same palette and standardized motifs in several copies of the same book, including another copy of the Gutenberg Bible now in Spain that is almost a twin of the Morgan's Old Testament.

Together, these three copies show how Gutenberg tackled a fundamental problem of technological innovation--the expectations of the consumer. Marketing considerations dictated the large size of this stately folio Bible, ideal for reading in a monastic refectory. It was never intended to be a luxury book, but it did have to contain heading and ornamentation that would help the reader navigate a long and complex text. Gutenberg had to allocate space that others would use at a later date to signal different sections of the Bible, either by writing in rubrics or by painting decorative initials. The Morgan's three copies show various techniques employed by the artists who fulfilled the inventor's intentions, as well as the artistry of the inventor himself, who succeeded in making a beautiful book while also starting a new chapter in the history of visual communication.