Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

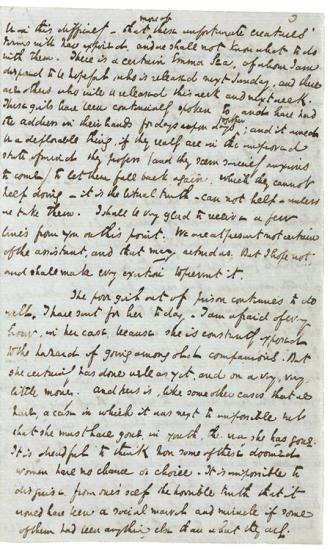

be in this difficulty—that more of these unfortunate creatures' terms will have expired, and we shall not know what to do with them. There is a certain Emma Lea, of whom I am disposed to be hopeful, who is released next Sunday, and there are others who will be released this week and next week. These girls have been continually spoken to, and have had the address in their hands for days upon days together; and it would be a deplorable thing, if they really are in the improved state of mind they profess (and they seem sincerely anxious to come) to let them fall back again. Which they cannot help doing—it is the literal truth—can not help—unless we take them. I shall be very glad to receive a few lines from you on this point. We are at present not certain of the assistant, and that may retard us. But I hope not, and shall make every exertion to prevent it

The poor girl out of prison continues to do well. I have sent for her to day. I am afraid of every hour, in her case, because she is constantly exposed to the hazard of going among old companions. But she certainly has done well as yet, and on a very, very little money. And hers is, like some other cases that we have, a case in which it was next to impossible but that she must have gone, in youth, the way she has gone. It is dreadful to think how some of these doomed women have no chance or choice. It is impossible to disguise from one's self the horrible truth that it would have been a social marvel and miracle if some of them had been anything else than what they are.