Autograph letter signed, London, 26 May 1846, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

This letter is the earliest in which Dickens makes reference to the project to create a home for prostitutes and petty miscreants that would become Urania Cottage. Dickens's fourteen-page letter sets out in detail his hopes and plans for the institution: "A woman or girl coming to the Asylum, it is explained to her that she has come there for useful repentance and reform, and because her past way of life has been dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself. Never mind Society while she is at that pass. Society has used her ill and turned away from her, and she cannot be expected to take much heed of its rights or wrongs." Dickens never used the term prostitute in any of his letters.

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

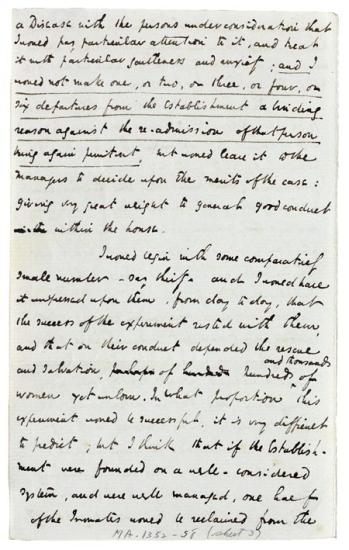

a Disease with the persons under consideration that I would pay particular attention to it, and treat it with particular gentleness and anxiety; and I would not make one, or two, or three, or four, or six departures from the Establishment a binding reason against the readmission of that person, being again penitent, but would leave it to the Managers to decide upon the merits of the case: giving very great weight to general good conduct within the house.

I would begin with some comparatively small number—say thirty—and I would have it impressed upon them, from day to day, that the success of the experiment rested with them, and that on their conduct depended the rescue and salvation, of hundreds and thousands of women yet unborn. In what proportion this experiment would be successful, it is very difficult to predict; but I think that if the Establishment were founded on a well-considered system, and were well managed, one half of the Inmates would be reclaimed from the