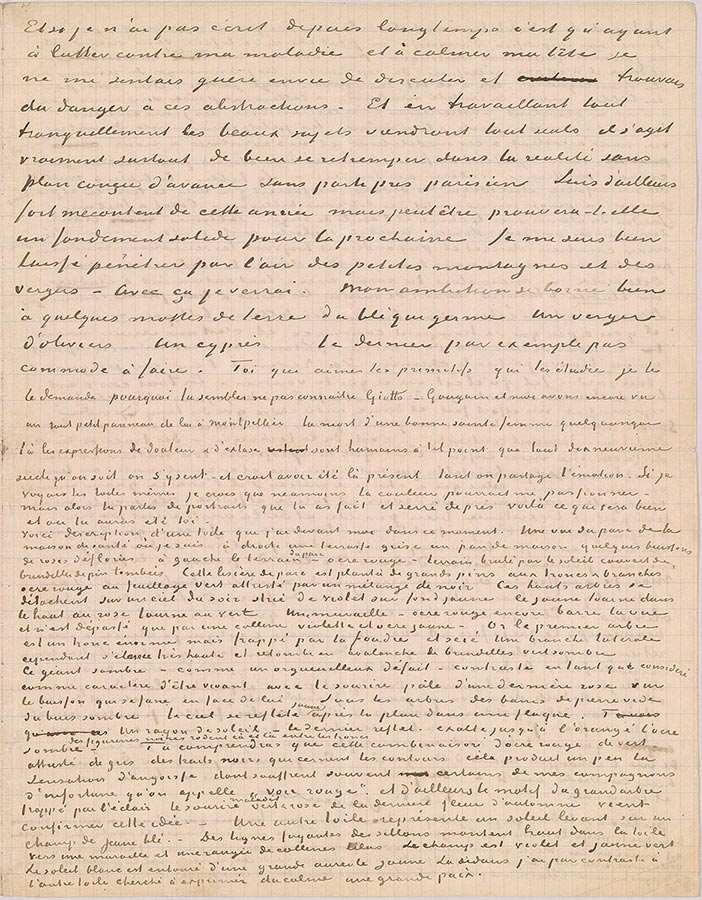

Letter 22, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Saint-Rémy, 20 November 1889, Letter 22, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

And if I haven't written for a long time, it's because, having to struggle against my illness and

to calm my head, I hardly felt like having discussions, and found danger in these abstractions.

And by working very calmly, beautiful subjects will come of their own accord; it's truly first and

foremost a question of immersing oneself in reality again, with no plan made in advance, with no

Parisian bias. Besides, am very dissatisfied with this year, but perhaps it will prove a solid foundation

for the coming one. I have let myself become thoroughly imbued with the air of the small

mountains and the orchards. With that, I'll see. My ambition is truly limited to a few clods of earth,

some sprouting wheat. An olive grove. A cypress; the latter not easy to do, for example. You who

love the primitives, who study them, I ask you why you appear not to know Giotto. Gauguin and I

saw a tiny panel of his in Montpellier, the death of some sainted woman or other. The expressions

in it of pain and ecstasy are human to the point that, nineteenth century though it may be, you feel

you're in it—and believe you were there, present, so much do you share the emotion. If I saw your

actual canvases, I believe the color could nevertheless excite me. But then you speak of portraits

that you have done, and have captured precisely; that's something that will be good, and where you

will have been yourself.

Here's a description of a canvas that I have in front of me at the moment. A view of the garden

of the asylum where I am, on the right a gray terrace, a section of house, some rosebushes that have

lost their flowers; on the left, the earth of the garden—red ocher—earth burnt by the sun, covered

in fallen pine twigs. This edge of the garden is planted with large pines with red ocher trunks and

branches, with green foliage saddened by a mixture of black. These tall trees stand out against an

evening sky streaked with violet against a yellow background. High up, the yellow turns to pink,

turns to green. A wall—red ocher again—blocks the view, and there is nothing above it but a violet

and yellow ocher hill. Now, the first tree is an enormous trunk, but struck by lightning and sawn

off. A side branch thrusts up very high, however, and falls down again in an avalanche of dark

green twigs.

This dark giant—like a proud man brought low—contrasts, when seen as the character of a

living being, with the pale smile of the last rose on the bush, which is fading in front of him. Under

the trees, empty stone benches, dark box. The sky is reflected yellow in a puddle after the rain. A

ray of sun—the last glimmer—exalts the dark ocher to orange—small dark figures prowl here and

there between the trunks. You'll understand that this combination of red ocher, of green saddened

with gray, of black lines that define the outlines, this gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from

which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer, and which is called "seeing red." And

what's more, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly green and pink smile of the

last flower of autumn, confirms this idea. Another canvas depicts a sun rising over a field of new

wheat. Receding lines of the furrows run high up on the canvas, toward a wall and a range of lilac

hills. The field is violet and green yellow. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow aureole.

In it, in contrast to the other canvas, I have tried to express calm, a great peace.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam