Letter 22, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Saint-Rémy, 20 November 1889, Letter 22, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear friend Bernard,

Thank you for your letter, and thank you especially for your photos, which give me an idea of your

work.

Incidentally, my brother wrote to me about it the other day, saying that he very much liked the

harmoniousness of the color, a certain nobility in several figures.

Look, in the adoration of the shepherds, the landscape charms me too much for me to dare to

criticize, and nevertheless, it's too great an impossibility to imagine a birth like that, on the very

road, the mother who starts praying instead of giving suck, the fat ecclesiastical bigwigs, kneeling as

if in an epileptic fit, God knows how or why they're there, but I myself don't find it healthy.

Because I adore the true, the possible, were I ever capable of spiritual fervor; so I bow before

that study, so powerful that it makes you tremble, by père Millet—peasants carrying to the farmhouse

a calf born in the fields. Now, my friend—people have felt that from France to America. After

that, would you go back to renewing medieval tapestries for us? Truly, is this a sincere conviction?

No, you can do better than that, and you know that one has to look for the possible, the logical, the

true, even if to some extent you had to forget Parisian things à la Baudelaire. How I prefer Daumier

to that gentleman!

An annunciation of what—I see figures of angels, elegant, my word, a terrace with two

cypresses, which I like very much; there's an enormous amount of air, of clarity in it. . . . but in the

end, once this first impression is past, I wonder if it's a mystification, and these secondary characters no longer tell me anything.

But this is enough for you to understand that I was longing to get to know things from you like

the painting of yours that Gauguin has, those Breton women walking in a meadow, the arrangement

of which is so beautiful, the color so naively distinguished. Ah, you're exchanging that for

something—must one say the word—something artificial—something affected.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 22, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Saint-Rémy, 20 November 1889, Letter 22, page 2

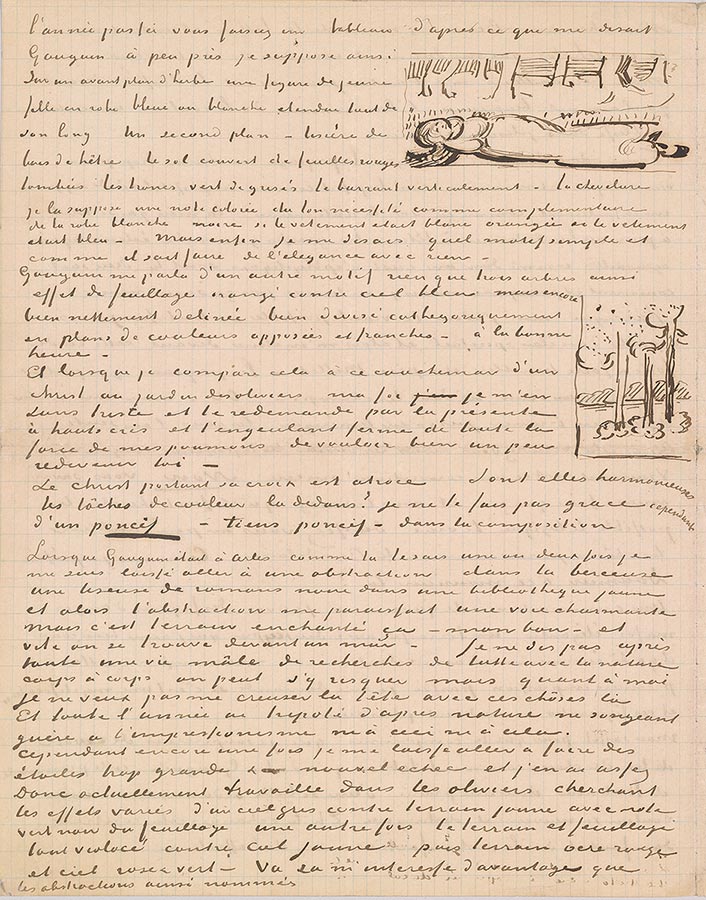

Reclining girl; Three trees

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Last year, from what Gauguin was telling me, you were doing a painting more or less like this,

I imagine. Against a foreground of grass, a figure of a young girl in a blue or white dress,

lying full length. Behind that: edge of a beech wood, the ground covered in fallen red leaves, the

verdigrised trunks crossing it vertically—I imagine the hair a colorful note in the tone required as

complementary to the white dress: black if the clothing was white, orange if the clothing was blue.

But anyway, I said to myself, what a simple subject, and how he knows how to create elegance with

nothing.

Gauguin spoke to me of another subject, nothing but three trees, thus the effect of orange

foliage against blue sky, but still really clearly delineated, well divided, categorically, into planes of

contrasting and pure colors—that's the spirit! And when I compare that with that nightmare

of a Christ in the Garden of Olives, well, it makes me feel sad, and I herewith ask you again,

crying out loud and giving you a good rocket with all the power of my lungs, to please become a

little more yourself again.

The Christ Carrying His Cross is atrocious. Are the splashes of color in it harmonious? But I

will not let you off the hook for a COMMONPLACE—commonplace, you hear—in the composition.

When Gauguin was in Arles, I once or twice allowed myself to be led into abstraction, as you know, in a woman rocking a cradle, a dark woman reading novels in a yellow library, and at

that time abstraction seemed an attractive route to me. But that's enchanted ground,—my good

fellow—and one soon finds oneself up against a wall. I'm not saying that one may not take the

risk after a whole manly life of searching, of fighting hand-to-hand with reality, but as far as I'm

concerned I do not want to rack my brains over that sort of thing. And the whole year, have fiddled

around from life, hardly thinking of impressionism or of this or that.

However, once again I'm allowing myself to do stars too big, etc., new setback, and I've enough

of that.

So at present am working in the olive trees, seeking the different effects of a gray sky against

yellow earth, with dark green note of the foliage; another time the earth and foliage all purplish

against yellow sky, then red ocher earth and pink and green sky. See, that interests me more than

the so-called abstractions.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 22, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Saint-Rémy, 20 November 1889, Letter 22, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

And if I haven't written for a long time, it's because, having to struggle against my illness and

to calm my head, I hardly felt like having discussions, and found danger in these abstractions.

And by working very calmly, beautiful subjects will come of their own accord; it's truly first and

foremost a question of immersing oneself in reality again, with no plan made in advance, with no

Parisian bias. Besides, am very dissatisfied with this year, but perhaps it will prove a solid foundation

for the coming one. I have let myself become thoroughly imbued with the air of the small

mountains and the orchards. With that, I'll see. My ambition is truly limited to a few clods of earth,

some sprouting wheat. An olive grove. A cypress; the latter not easy to do, for example. You who

love the primitives, who study them, I ask you why you appear not to know Giotto. Gauguin and I

saw a tiny panel of his in Montpellier, the death of some sainted woman or other. The expressions

in it of pain and ecstasy are human to the point that, nineteenth century though it may be, you feel

you're in it—and believe you were there, present, so much do you share the emotion. If I saw your

actual canvases, I believe the color could nevertheless excite me. But then you speak of portraits

that you have done, and have captured precisely; that's something that will be good, and where you

will have been yourself.

Here's a description of a canvas that I have in front of me at the moment. A view of the garden

of the asylum where I am, on the right a gray terrace, a section of house, some rosebushes that have

lost their flowers; on the left, the earth of the garden—red ocher—earth burnt by the sun, covered

in fallen pine twigs. This edge of the garden is planted with large pines with red ocher trunks and

branches, with green foliage saddened by a mixture of black. These tall trees stand out against an

evening sky streaked with violet against a yellow background. High up, the yellow turns to pink,

turns to green. A wall—red ocher again—blocks the view, and there is nothing above it but a violet

and yellow ocher hill. Now, the first tree is an enormous trunk, but struck by lightning and sawn

off. A side branch thrusts up very high, however, and falls down again in an avalanche of dark

green twigs.

This dark giant—like a proud man brought low—contrasts, when seen as the character of a

living being, with the pale smile of the last rose on the bush, which is fading in front of him. Under

the trees, empty stone benches, dark box. The sky is reflected yellow in a puddle after the rain. A

ray of sun—the last glimmer—exalts the dark ocher to orange—small dark figures prowl here and

there between the trunks. You'll understand that this combination of red ocher, of green saddened

with gray, of black lines that define the outlines, this gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from

which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer, and which is called "seeing red." And

what's more, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly green and pink smile of the

last flower of autumn, confirms this idea. Another canvas depicts a sun rising over a field of new

wheat. Receding lines of the furrows run high up on the canvas, toward a wall and a range of lilac

hills. The field is violet and green yellow. The white sun is surrounded by a large yellow aureole.

In it, in contrast to the other canvas, I have tried to express calm, a great peace.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 22, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Saint-Rémy, 20 November 1889, Letter 22, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I am speaking to you of these two canvases, and especially the first, to remind you that in order

to give an impression of anxiety, you can try to do it without heading straight for the historical

garden of Gethsemane; in order to offer a consoling and gentle subject it is not necessary to depict

the figures from the Sermon on the Mount—ah—it is—no doubt—wise, right, to be moved by

the Bible, but modern reality has such a hold over us that even when trying abstractly to reconstruct

ancient times in our thoughts—just at that very moment the petty events of our lives tear us

away from these meditations and our own adventures throw us forcibly into personal sensations:

joy, boredom, suffering, anger or smiling. The Bible—the Bible—Millet was brought up on it from

his childhood, used to read only that book and yet never, or almost never, did biblical paintings.

Corot did a Garden of Olives with Christ and the star of Bethlehem: sublime. In his work you

feel Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles too, sometimes, as well as the gospels, but how sober and always

giving due weight to modern, possible sensations common to us all. But, you'll say, Delacroix—yes,

Delacroix—but then you'd have to study in a very different way, yes, study history before putting

things in their place like that.

So, they're a setback, my dear fellow, your biblical paintings, but. . . . there are few who make

mistakes like that, and it's an error, but your return from it will be, I dare to say, astonishing, and

it's by making mistakes that one sometimes finds the way. Look, avenge yourself by painting your

garden as it is, or anything you like. In any case, it's good to look for what's distinguished, what's

noble in figures, and your studies represent an effort that's been made, and so something other

than wasted time.

To know how to divide a canvas into large, tangled planes like that, to find contrasting lines

and forms—that's technique—trickery, if you like, but anyway, it means you're learning your craft

more thoroughly, and that's good. No matter how hateful and cumbersome painting may be in the

times in which we live, the person who has chosen this craft, if he nevertheless practices it with

zeal, is a man of duty, both sound and loyal. Society sometimes makes existence very hard for us,

and from that too comes our impotence and the imperfection of our works. I believe that Gauguin

himself suffers greatly from it, too, and cannot develop as he yet has it in him to do.

I myself suffer in that I'm utterly without models. On the other hand, there are beautiful sites

here. Have just done five no. 30 canvases of the olive trees. And if I still stay here it's because my

health is recovering greatly. What I'm making is harsh, dry, but it's because I'm trying to reinvigorate

myself by means of rather arduous work, and would fear that abstractions would make me

soft. Have you seen a study of mine with a little reaper? A field of yellow wheat and a yellow sun.

It isn't there yet—but in it I have again attacked this devil of a question of yellow. I'm talking about

the one that's impastoed and done on the spot, not about the repetition with hatching, in which

the effect is weaker. I wanted to do it in pure sulphur. I'd have plenty more things to tell you—but although I write today that my mind is somewhat stronger, previously I was afraid of overheating it

before I was cured. In thought a very warm handshake, to Anquetin too, to other friends if you see

them, and believe me,

Ever yours,

Vincent

No need to tell you that I regret, for you as well as for your father, that he did not approve of your

spending the season with Gauguin. The latter wrote to me that for reasons of health your service

has been postponed for a year. Thank you anyway for the description of the Egyptian house. I

would still have liked to know if it was larger or smaller than a cottage back home—the size relative

to the human figure, in short. I was looking for information about the coloring in particular.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam