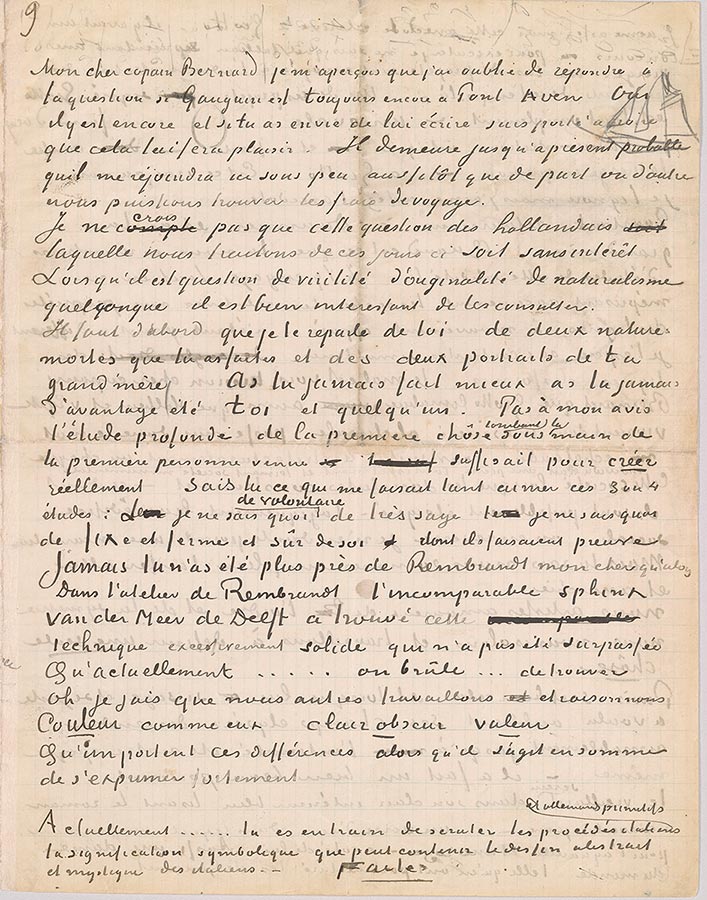

Letter 14, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 5 August 1888, Letter 14, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard,

I realize that I've forgotten to answer your question as to whether Gauguin is still in Pont-Aven.

Yes, he's still there, and if you feel like writing to him am inclined to believe that it will please him.

It is still likely that he will join me here shortly, as soon as either one of us is able to find the travel

expenses.

I do not believe that this question of the Dutchmen, which we're discussing these days, is without

interest. It is quite interesting to consult them when it's a matter of any kind of virility, originality,

naturalism.

In the first place, I must speak to you again about yourself, about two still lifes that you have

done, and about the two portraits of your grandmother. Have you ever done better, have you ever

been more yourself, and somebody? Not in my opinion. Profound study of the first thing to come

to hand, of the first person to come along, was enough to really create something. Do you know

what made me like these three or four studies so much? That je ne sais quoi of something deliberate,

very wise, that je ne sais quoi of something steady and firm and sure of oneself, which they

show. You have never been closer to Rembrandt, my dear chap, than then. In Rembrandt's studio,

the incomparable sphinx, Vermeer of Delft, found this extremely sound technique that has not

been surpassed. Which today . . . we're burning . . . to find. Oh, I know that we are working and

arguing COLOR as they did chiaroscuro, value.

What do these differences matter when in the end it's a question of expressing oneself powerfully?

At present . . . you're examining primitive Italian and German techniques, the symbolic meaning

that the Italians' abstract and mystical drawing may contain. Do so.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

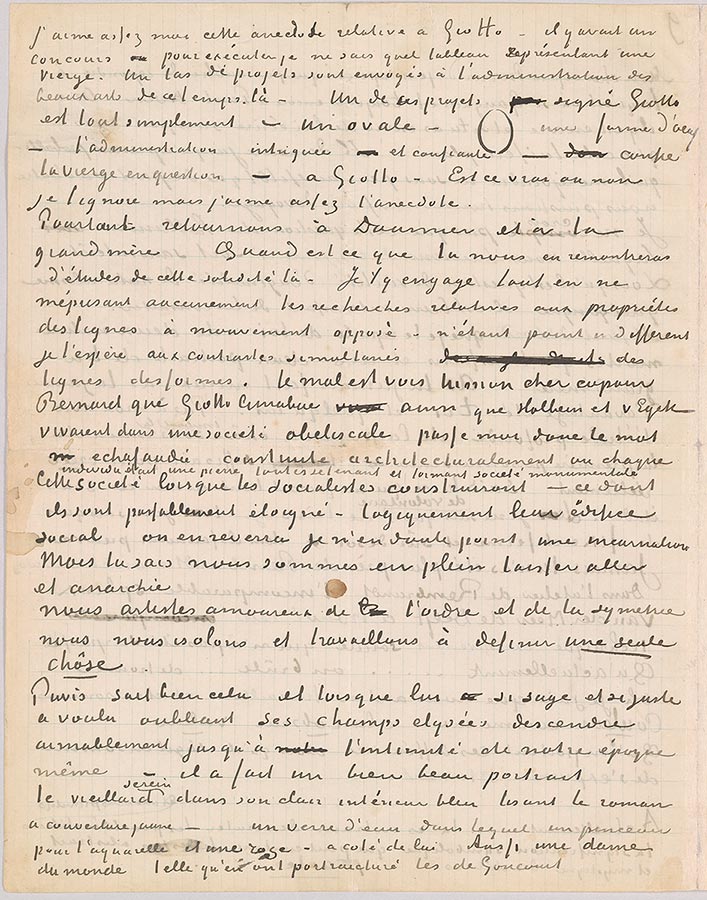

Letter 14, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 5 August 1888, Letter 14, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I myself rather like this anecdote about Giotto—there was a competition for the execution of

some painting or other of a Virgin. Lots of proposals were sent to the fine arts authorities of those

days. One of these proposals, signed Giotto, was simply—an oval—[sketch] an egg shape—the

authorities, intrigued and trusting—entrust the Virgin in question—to Giotto. Whether it's true

or not, I don't know, but I rather like the anecdote.

However, let's return to Daumier and to your grandmother. When are you going to show us

more of them, studies of that soundness? I urge you to do so, while at the same time in no way

belittling your investigations concerning the properties of lines in contrary motion—being not at

all indifferent, I hope, to the simultaneous contrasts of lines, of forms. The trouble is, do you see,

my dear old Bernard, that Giotto, Cimabue, as well as Holbein and van Eyck, lived in an obeliscal—

if you'll pardon the expression—society, layered, architecturally constructed, in which each

individual was a stone, all of them holding together and forming a monumental society. I have

no doubt that we'll again see an incarnation of this society when the socialists logically build their

social edifice—from which they're a fair distance away yet. But you know we're in a state of total

laxity and anarchy.

We, artists in love with order and symmetry, isolate ourselves and work to define one single

thing.

Puvis knows that very well, and when he, so wise and so just, decided to descend goodnaturedly

into the intimacy of our very own epoch, forgetting his Elysian Fields, he made a

very fine portrait, the serene old man in his bright, blue interior, reading the novel with a yellow

cover—a glass of water beside him, in which a watercolor brush and a rose. And also a society lady,

like those the de Goncourts portrayed.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

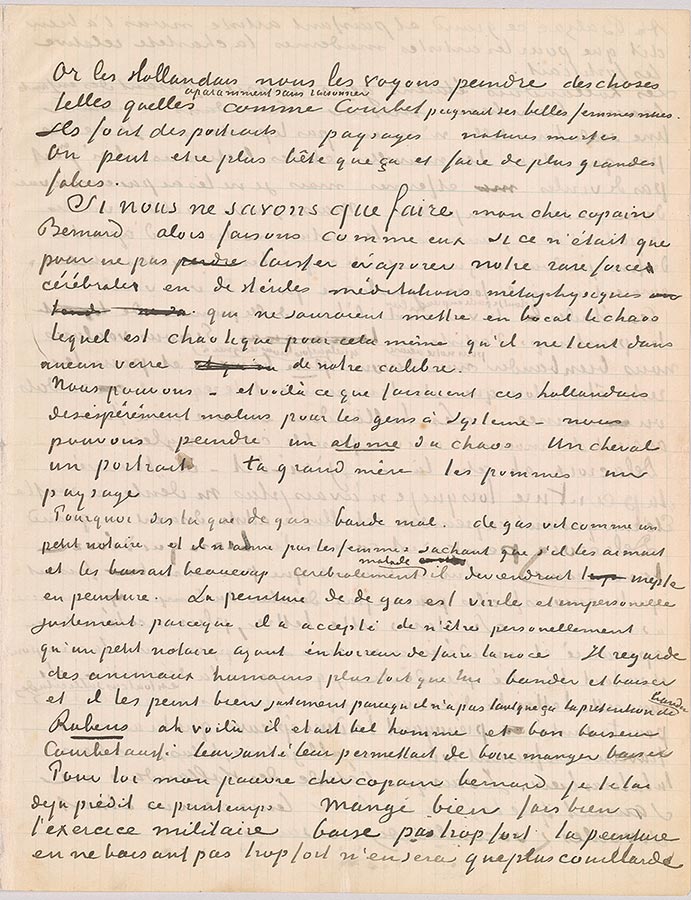

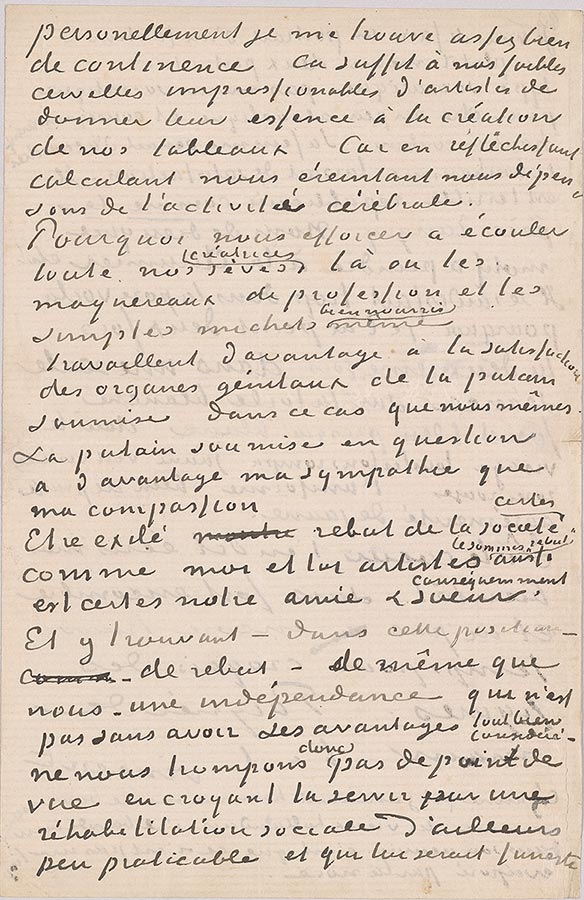

Letter 14, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 5 August 1888, Letter 14, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

The Dutchmen, now, we see them painting things just as they are, apparently without thought,

the way Courbet painted his beautiful naked women.

They make portraits, landscapes, still lifes. One could be stupider than that and commit greater

follies.

If we do not know what to do, my dear old Bernard, then let's do the same as they, if only so as

not to allow our scarce mental powers to evaporate in sterile metaphysical meditations that aren't

up to bottling chaos, which is chaotic for the very reason that it won't fit into any glass of our caliber.

We can—and that's what those Dutchmen did, desperately clever in the eyes of people wedded

to system—we can paint an atom of chaos. A horse, a portrait, your grandmother, apples, a landscape.

Why do you say that Degas has trouble getting a hard-on? Degas lives like a little lawyer, and he

doesn't like women, knowing that if he liked them and fucked them a lot he would become cerebrally

ill and hopeless at painting. Degas's painting is virile and impersonal precisely because he has

resigned himself to being personally no more than a little lawyer, with a horror of riotous living. He

watches human animals stronger than himself getting a hard-on and fucking, and he paints them

well, precisely because he doesn't make such great claims about getting a hard-on.

Rubens, ah, there you have it, he was a handsome man and a good fucker, Courbet too;

their health allowed them to drink, eat, fuck.

In your case, my poor dear old Bernard, I already told you last spring. Eat well, do your military

drill well, don't fuck too hard; if you don't fuck too hard, your painting will be all the spunkier

for it.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

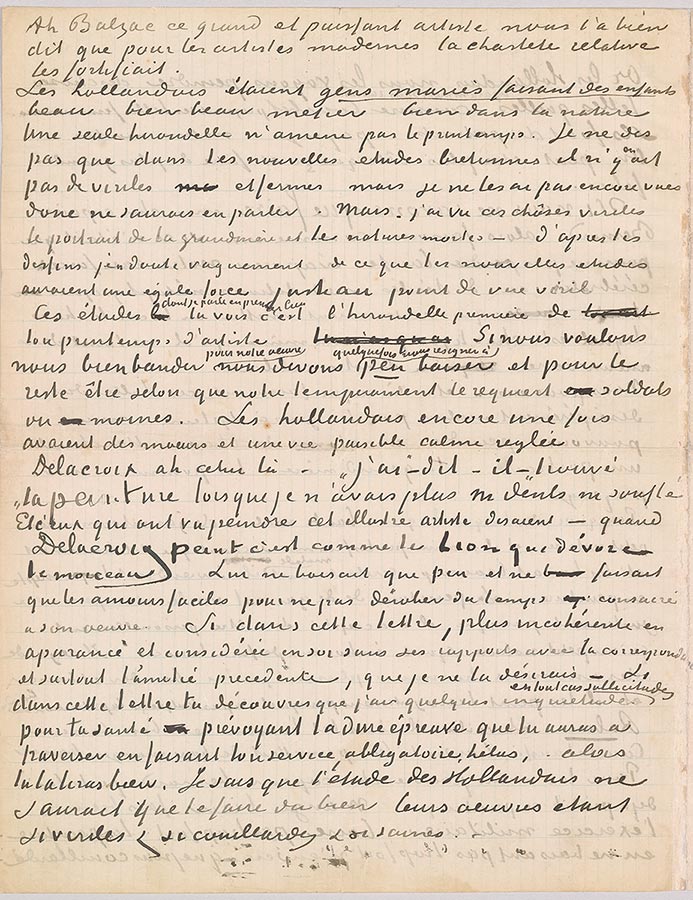

Letter 14, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 5 August 1888, Letter 14, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Ah, Balzac, that great and powerful artist, already told us very well that for modern artists a

certain chastity made them stronger.

The Dutchmen were married people making children, a beautiful, very beautiful occupation,

very natural.

One swallow doesn't make a summer. I'm not saying that among your new Breton studies there

aren't some virile and strong ones, but I haven't seen them yet and so wouldn't be able to talk about

them. But—I have seen those virile things, the portrait of your grandmother and the still lifes—

judging from your drawings I have vague doubts whether these new studies would have the same

vigor, just from the virile point of view.

These studies that I'm talking about first, you see it's the first swallow of your summertime as

an artist. If we want, ourselves, to get a hard-on for our work, we must sometimes resign ourselves

to fucking only a little, and for the rest to be, according as our temperament demands, soldiers or

monks. The Dutchmen, once again, had morals, and a quiet, calm, well-ordered life.

Delacroix, ah, him—"I," he said, "found painting when I had no teeth nor breath left." And

those who saw this famous artist paint said: when Delacroix paints it's like the lion devouring his

piece of flesh. He fucked only a little, and had only casual love affairs so as not to filch from the

time devoted to his work. If in this letter, on the face of it more incoherent, and taken on its own

without its connections to the previous correspondence and above all, friendship, than I should

wish—If in this letter you find that I have some anxieties—concerns in any case—for your health,

foreseeing the hard ordeal that you'll have to go through in doing your service, obligatory, alas,—

then you will read it correctly. I know that the study of the Dutchmen could only do you good,

their works being so virile and so spunky and so healthy.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 14, page 5

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles,5 August 1888, Letter 14, page 5

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Personally, I find continence is quite good for me. It's enough for our weak, impressionable

artists' brains to give their essence to the creation of our paintings. Because in thinking, calculating,

wearing ourselves out, we expend cerebral activity.

Why exert ourselves in spending all our creative juices when those who pimp for a living

and even their simple, well-fed clients work more to the satisfaction of the genital organs of the

registered whore in this case than we do? The whore in question has my sympathy more than my

compassion.

Being exiled, a social outcast, as artists like you and I surely are, also "outcasts," she is surely

therefore our friend and sister. And finding—in this position—of outcast—the same as us—an

independence that is not without its advantages—all things considered—let's not adopt a false

position by believing we're serving her through social rehabilitation, which is in any case impractical

and would be fatal for her.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

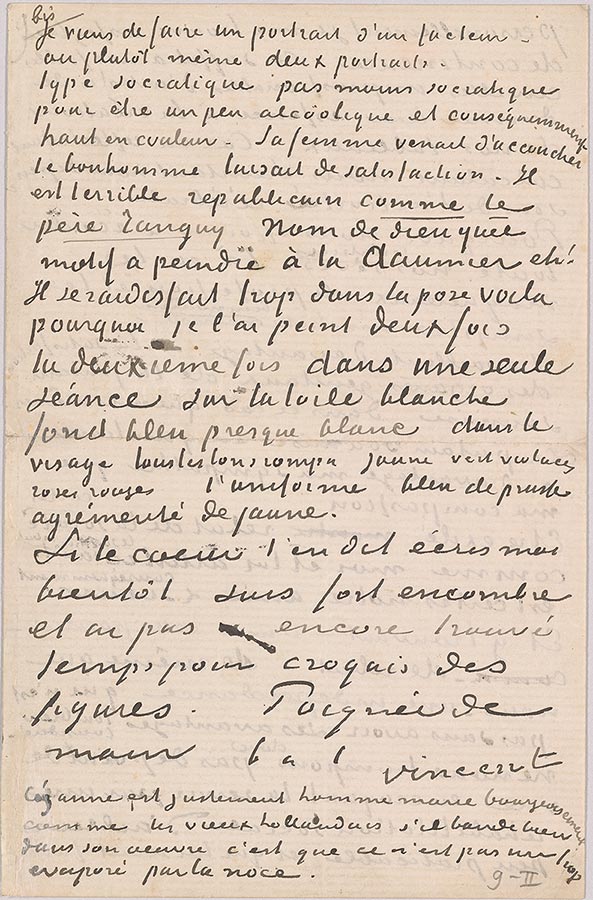

Letter 14, page 6

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 5 August 1888, Letter 14, page 6

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I have just made a portrait of a postman—or rather, two portraits even—Socratic type, no

less Socratic for being something of an alcoholic, and with a high color as a result. His wife had

just given birth, the good fellow was glowing with satisfaction. He's a fierce republican, like père

Tanguy. Goddamn, what a subject to paint à la Daumier, eh? He was getting too stiff while posing,

and that's why I painted him twice, the second time at a single sitting, on white canvas, background

blue, almost white, in the face all the broken tones: yellow, green, purples, pinks, reds, the uniform

Prussian blue trimmed with yellow.

Write to me soon if you feel like it; am very encumbered and have not yet found time for figure

sketches. Handshake

Yours,

Vincent

Cézanne is as much a respectably married man as the old Dutchmen were. If he has a good hard-on

in his work it's because he's not overly dissipated through riotous living.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam