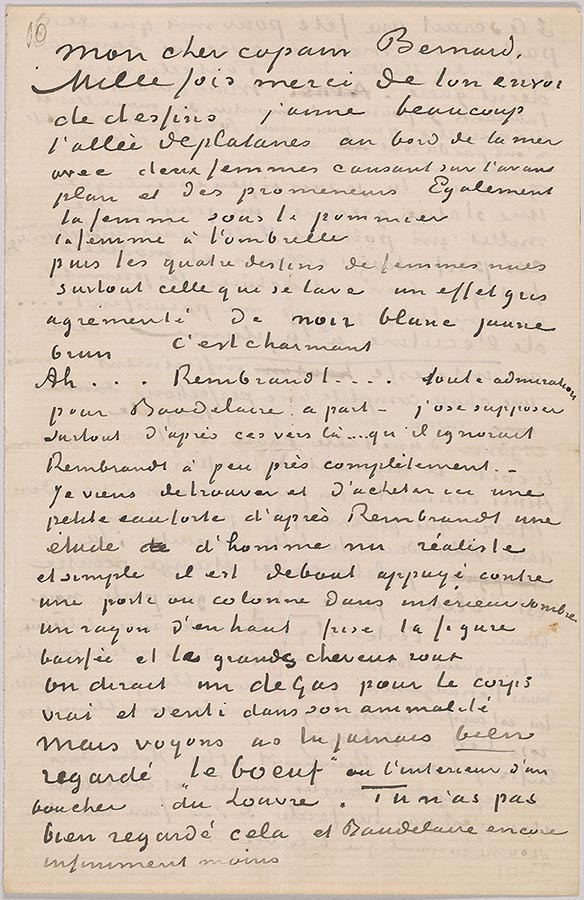

Letter 12, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

My dear old Bernard,

A thousand thanks for sending your drawings; I very much like the avenue of plane trees beside the

sea with two women chatting in the foreground and the promenaders. Also

the woman under the apple tree

the woman with the parasol

then the four drawings of nude women, especially the one washing herself, a gray effect embellished

with black, white, yellow, brown. It's charming.

Ah . . . Rembrandt . . . all admiration for Baudelaire aside—I venture to assume, especially on the

basis of those verses . . . that he knew more or less nothing about Rembrandt. I have just found and

bought here a little etching after Rembrandt, a study of a nude man, realistic and simple; he's standing,

leaning against a door or column in a dark interior. A ray of light from above skims his downturned

face and the bushy red hair.

You'd think it a Degas for the body, true and felt in its animality.

But see, have you ever looked closely at "The Ox" or the Interior of a Butcher's Shop in the Louvre?

You haven't looked closely at them, and Baudelaire infinitely less so.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

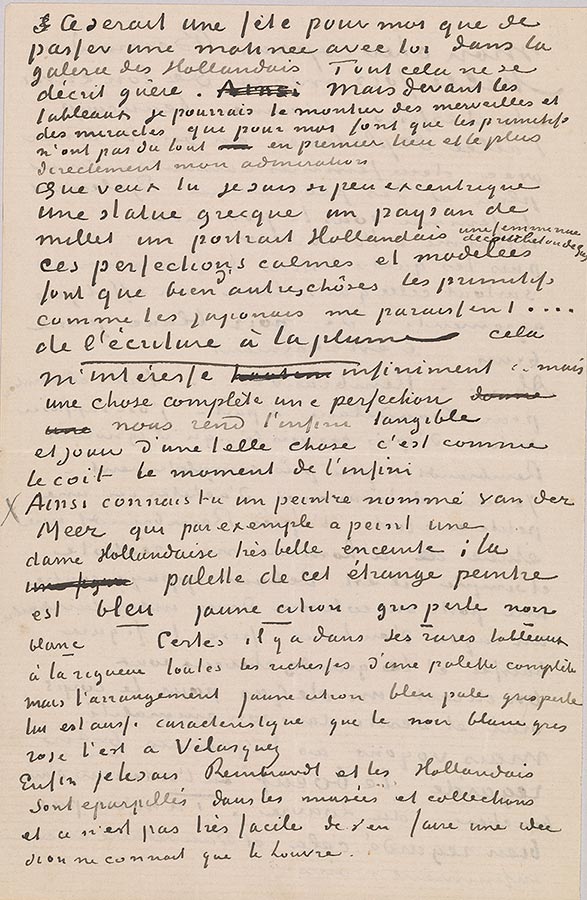

Letter 12, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

It would be a treat for me to spend a morning with you in the Dutch gallery. All that is barely

describable. But in front of the paintings I could show you marvels and miracles that are the reason

that, for me, the primitives really don't have my admiration first and foremost and most directly.

But there you are; I'm so far from eccentric. A Greek statue, a peasant by Millet, a Dutch portrait, a

nude woman by Courbet or Degas, these calm and modeled perfections are the reason that many other

things, the primitives as well as the Japanese, seem to me . . . like WRITING WITH A PEN; they interest me

infinitely . . . but something complete, a perfection, makes the infinite tangible to us.

And to enjoy such a thing is like coitus, the moment of the infinite.

For instance, do you know a painter called Vermeer, who, for example, painted a very beautiful

Dutch lady, pregnant? This strange painter's palette is blue, lemon yellow, pearl gray, black, white. Of

course, in his few paintings there are, if it comes to it, all the riches of a complete palette, but the

arrangement of lemon yellow, pale blue, pearl gray is as characteristic of him as the black, white, gray,

pink is of Velázquez.

Anyway, I know, Rembrandt and the Dutch are scattered around museums and collections, and

it's not very easy to form an idea of them if you only know the Louvre.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

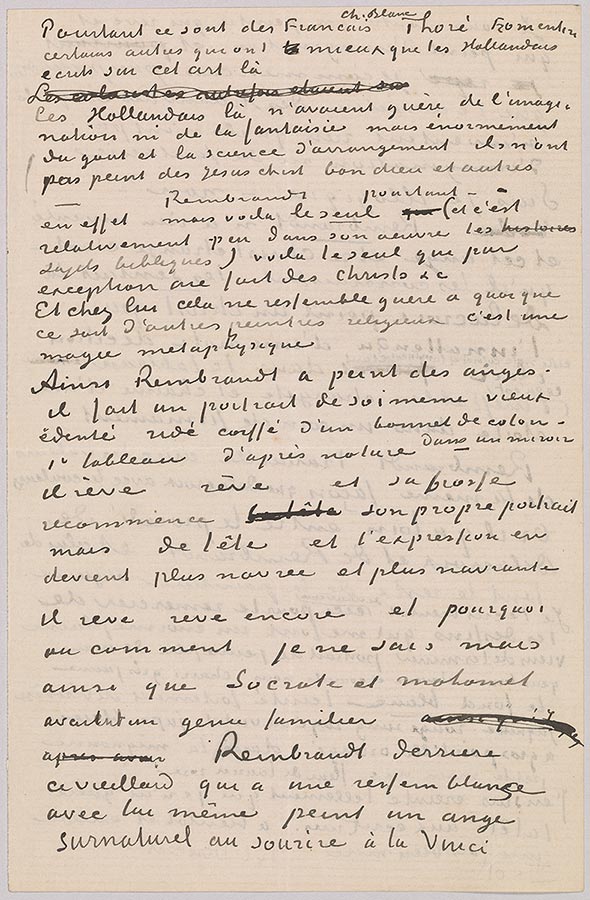

Letter 12, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

However, it's Frenchmen, C. Blanc, Thoré, Fromentin, certain others who have written better

than the Dutch on that art.

Those Dutchmen had scarcely any imagination or fantasy but great taste and the art of arrangement;

they did not paint Jesus Christs, the Good Lord and others. Rembrandt though—indeed, but

he's the only one (and there are relatively few biblical subjects in his oeuvre), he's the only one who,

as an exception, did Christs, etc.

And in his case, they hardly resemble anything by other religious painters; it's a metaphysical magic.

So, Rembrandt painted angels—he makes a portrait of himself as an old man, toothless, wrinkled,

wearing a cotton cap—first, painting from life in a mirror—he dreams, dreams, and his brush

begins his own portrait again, but from memory, and its expression becomes sadder and more

saddening; he dreams, dreams on, and why or how I do not know, but just as Socrates and Mohammed

had a familiar genie, Rembrandt, behind this old man who bears a resemblance to himself, paints a

supernatural angel with a da Vinci smile.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

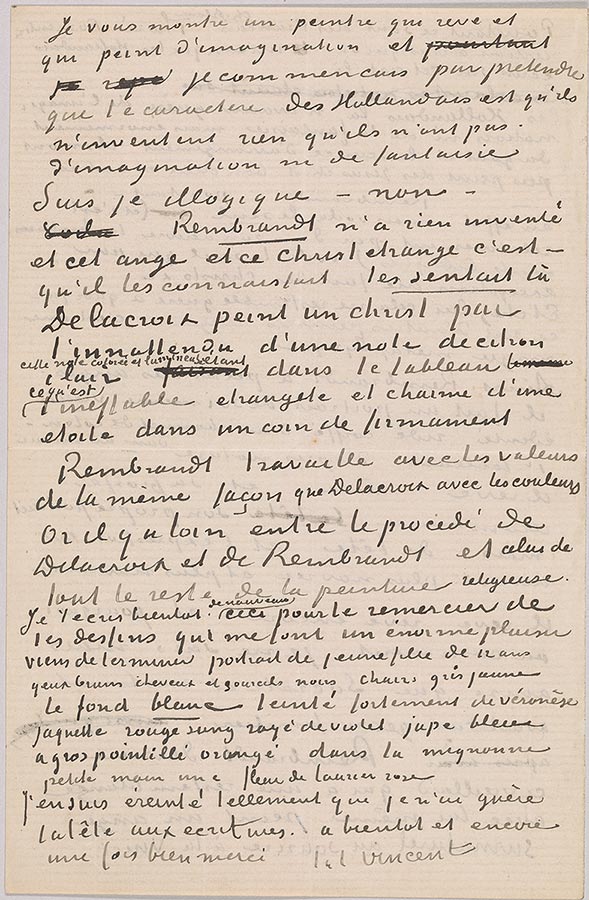

Letter 12, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 29 July 1888, Letter 12, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

I'm showing you a painter who dreams and who paints from the imagination, and I started off by

claiming that the character of the Dutch is that they invent nothing, that they have neither imagination

nor fantasy.

Am I illogical? No. Rembrandt invented nothing, and that angel and that strange Christ; it's—

that he knew them, felt them there.

Delacroix paints a Christ using an unexpected light lemon note, this colorful and luminous note

in the painting being what the ineffable strangeness and charm of a star is in a corner of the firmament.

Rembrandt works with values in the same way as Delacroix with colors.

Now, there's a gulf between the method of Delacroix and Rembrandt and that of all the rest of

religious painting.

I 'll write to you again soon. This to thank you for your drawings, which give me enormous pleasure.

Have just finished portrait of young girl of twelve, brown eyes, black hair and eyebrows, flesh yellow

gray, the background white, strongly tinged with veronese, jacket blood-red with violet stripes, skirt

blue with large orange spots, an oleander flower in her sweet little hand.

I'm so worn out from it that I hardly have a head for writing. So long, and again, many thanks.

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam