Letter 6, page 1

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 1

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

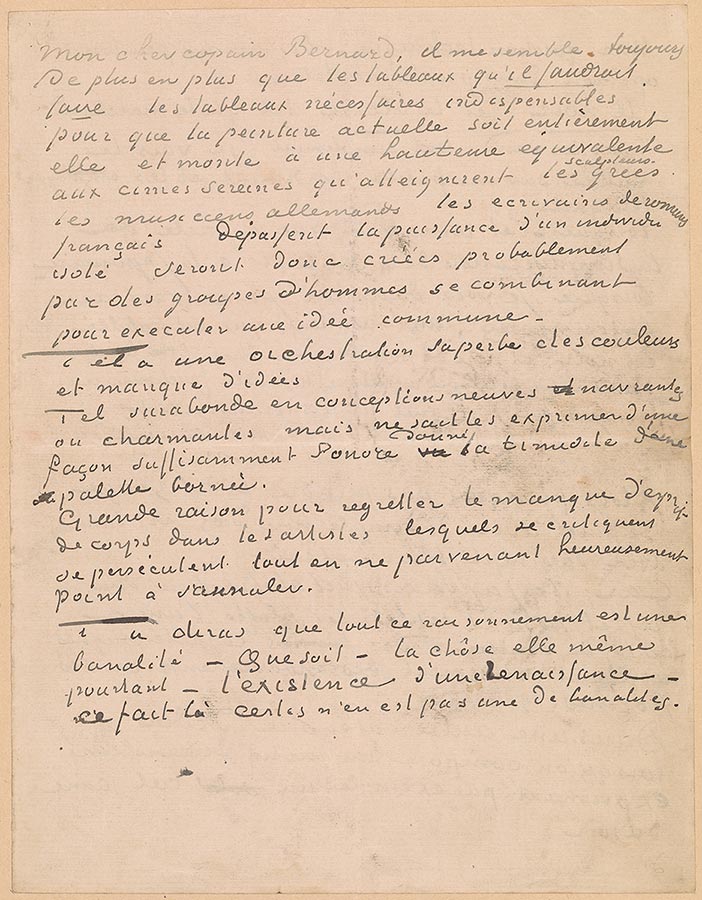

My dear old Bernard,

More and more it seems to me that the paintings that ought to be made, the paintings that are

necessary, indispensable for painting today to be fully itself and to rise to a level equivalent to the

serene peaks achieved by the Greek sculptors, the German musicians, the French writers of novels,

exceed the power of an isolated individual, and will therefore probably be created by groups of men

combining to carry out a shared idea.

One has a superb orchestration of colors and lacks ideas.

The other overflows with new, harrowing or charming conceptions but is unable to express

them in a way that is sufficiently sonorous, given the timidity of a limited palette.

Very good reason to regret the lack of an esprit de corps among artists, who criticize each

other, persecute each other, while fortunately not succeeding in canceling each other out.

You'll say that this whole argument is a banality. So be it—but the thing itself—the existence

of a Renaissance—that fact is certainly not a banality.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 6, page 2

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 2

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

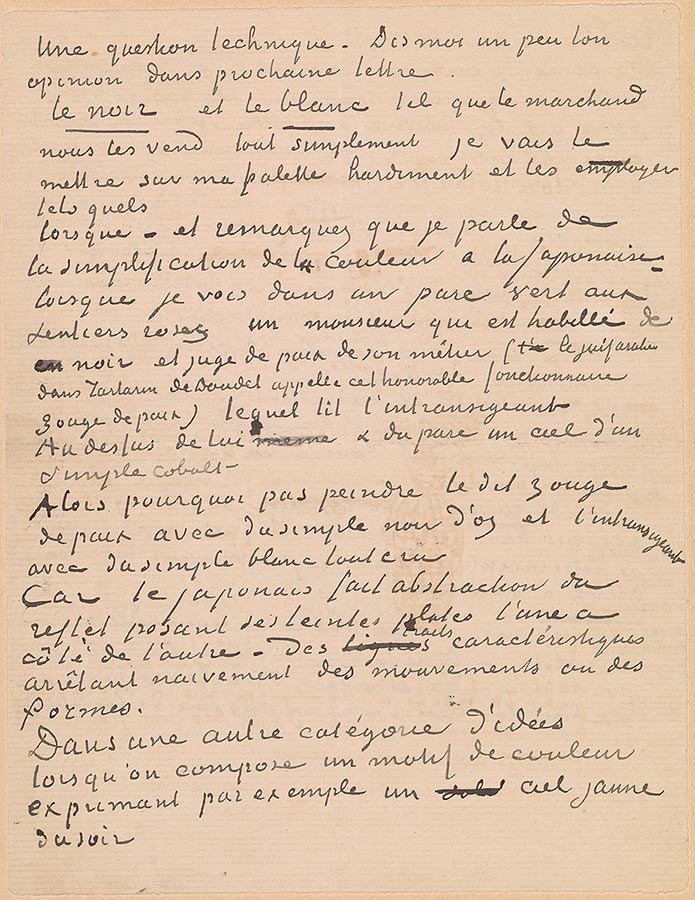

A technical question. Do give me your opinion in next letter.

I'm going to put the black and the white boldly on my palette, just the way the colorman sells

them to us, and use them as they are.

When—and note that I'm talking about the simplification of color in the Japanese manner—

when I see in a green park with pink paths a gentleman who is dressed in black, and a justice of the

peace by profession (the Arab Jew in Daudet's Tartarin calls this honorable official "shustish of the beace"), who's reading L'Intransigeant.

Above him and the park a sky of a simple cobalt.

Then why not paint the said shustish of the beace with simple bone black and L'Intransigeant

with simple, very harsh white?

Because the Japanese disregards reflection, placing his solid tints one beside the other—

characteristic lines naively marking off movements or shapes.

In another category of ideas, when you compose a color motif expressing, for example, a

yellow evening sky.

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 6, page 3

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 3

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

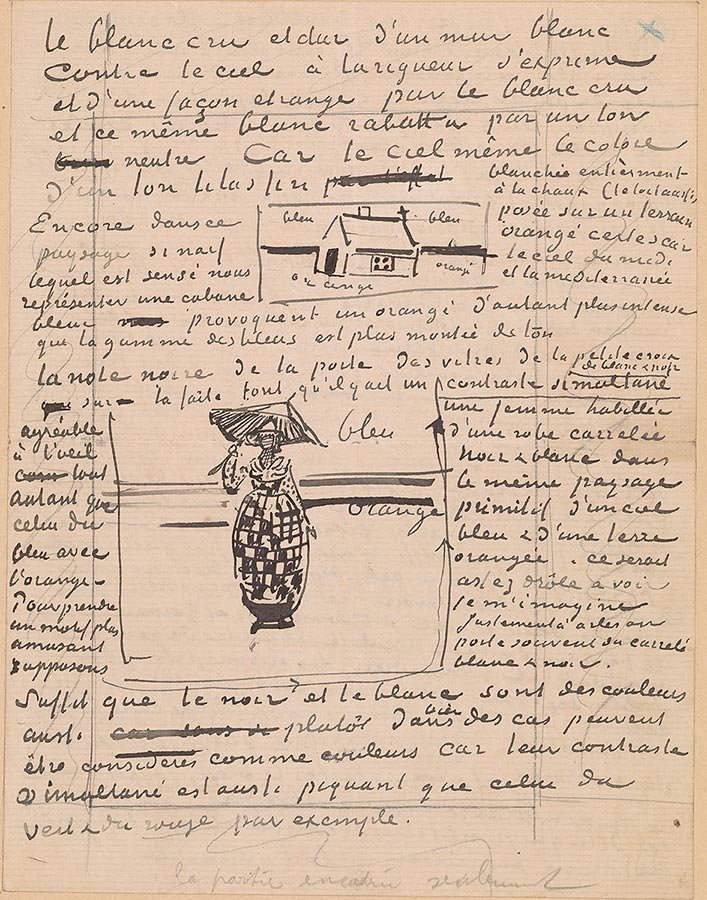

The harsh, hard white of a white wall against the sky can be expressed, at a pinch and in a

strange way, by harsh white and by that same white softened by a neutral tone. Because the sky

itself colors it with a delicate lilac hue. Again, in this very naive landscape, which is meant

to show us a hut, whitewashed overall (the roof, too), placed in an orange field, of course, because

the sky in the south and the blue Mediterranean produce an orange that is all the more intense

the higher in tint the range of blues.

The black note of the door, of the windowpanes, of the little cross on the rooftop creates a

simultaneous contrast of white and black just as pleasing to the eye as that of the blue

with the orange.

To take a more entertaining subject, let's imagine a woman dressed in a black and white

checked dress, in the same primitive landscape of a blue sky and an orange earth—that would

be quite amusing to see, I imagine. In fact, in Arles they often do wear white and black checks.

In short, black and white are colors too, or rather, in many cases may be considered colors, since their simultaneous contrast is as sharp as that of green and red, for example.

>© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Letter 6, page 4

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 4

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

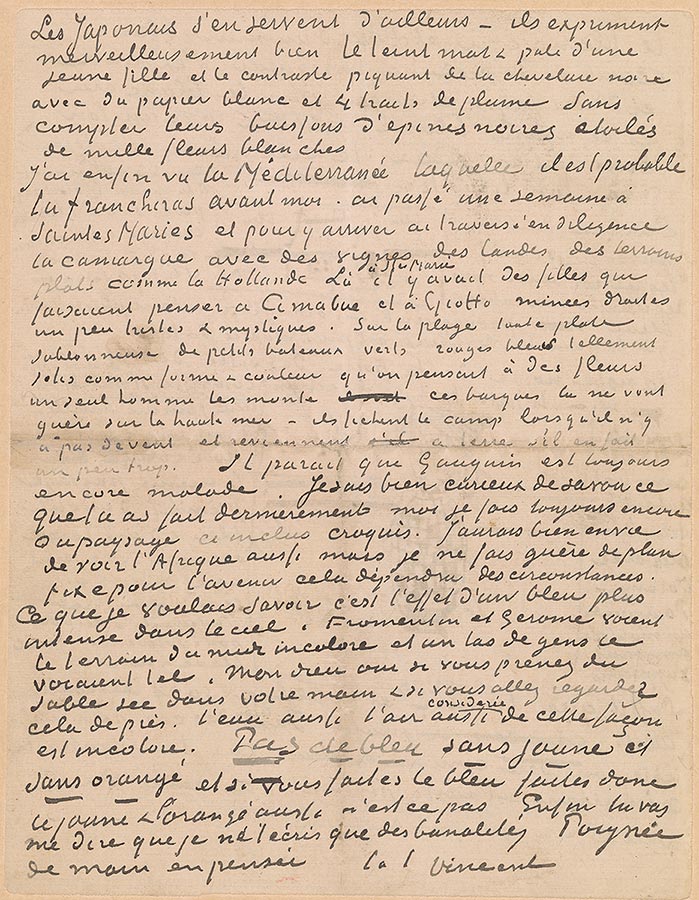

The Japanese use it too, by the way—they express a young girl's matte and pale complexion,

and its sharp contrast with her black hair wonderfully well with white paper and four strokes of the

pen. Not to mention their black thornbushes, studded with a thousand white flowers.

I've finally seen the Mediterranean, which you will probably cross before I do. Spent a week

in Saintes-Maries, and to get there crossed the Camargue in a diligence, with vineyards, heaths,

fields as flat as Holland. There, at Saintes-Maries, there were girls who made one think of Cimabue

and Giotto: slim, straight, a little sad and mystical. On the completely flat, sandy beach, little

green, red, blue boats, so pretty in shape and color that one thought of flowers; one man boards

them, these boats hardly go on the high sea—they dash off when there's no wind and come back to

land if there's a bit too much. It appears that Gauguin is still ill. I'm quite curious to know what

you've done lately; I'm still doing landscapes, sketch enclosed. I'd very much like to see Africa too,

but I hardly make any firm plans for the future, it will depend on circumstances. What I should like

to know is the effect of a more intense blue in the sky. Fromentin and Gérôme see the earth in

the south as colorless, and a whole lot of people saw it that way. My God, yes, if you take dry sand

in your hand and if you look at it closely. Water, too, air, too, considered this way, are colorless. No

BLUE WITHOUT YELLOW and WITHOUT ORANGE, and if you do blue, then do yellow and orange as

well, surely. Ah well, you'll tell me that I write you nothing but banalities. Handshake in thought,

Ever yours,

Vincent

© 2007 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

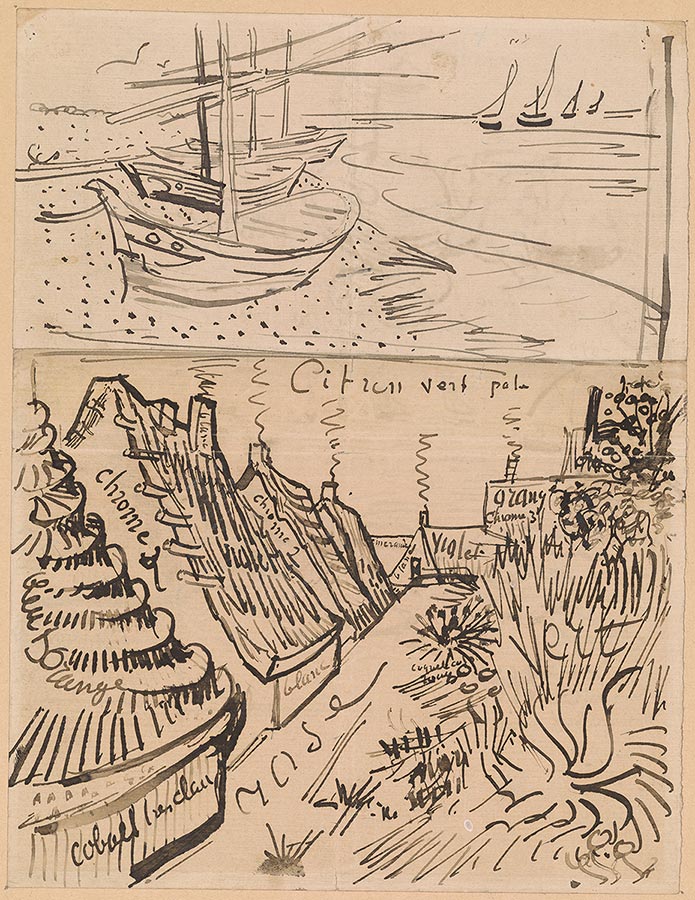

Letter 6, page 5

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 5

Street in Saintes-Maries

Fishing boats on the beach

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Van Gogh deeply felt the need for a lively dialogue and collaboration among artists. He argued that for modern art to rival, for example, the accomplishments of ancient Greek sculptors, artists should work collectively on a shared idea, since the "paintings that ought to be made . . . exceed the power of an isolated individual." Included in this letter is a sketch of a still life with a blue enameled coffeepot. Bernard would have recognized it as an homage to his own painting made six months earlier while the two artists were in Paris. The sketch of the street in Saintes-Maries documents his freshly painted canvas, with copious notations of the pairs of complementary colors he employed.

Upon his return from an intensely productive journey to the seaside town of Saintes-Maries, van Gogh sent this letter with a sheet of sketches enclosed to Bernard. The care he took with the drawings shows that he was eager to communicate the excitement of his work resulting from the trip. Inspired by the vibrant and constantly changing colors of the Mediterrenean, he described the beached fishing boats as being "so pretty in shape and color that one thought of flowers." He included a quick sketch of the boats along with outlines of another seascape, and two landscapes he was working on. In the letter he continued to discuss his theories about color and the use of black and white, adding a sketch of a woman in a black and white checked dress to emphasize the need to use such pigments boldly. He then jotted down a small sketch of one of the local cottages that became the subject for several drawings and paintings.

Letter 6, page 6

Vincent van Gogh, letter to Émile Bernard, Arles, 7 June 1888, Letter 6, page 6

Still life with coffee pot

Fishing boats at sea; Landscape with edge of a road; Farm along a road

Thaw Collection, given in honor of Charles E. Pierce, Jr., 2007

Van Gogh deeply felt the need for a lively dialogue and collaboration among artists. He argued that for modern art to rival, for example, the accomplishments of ancient Greek sculptors, artists should work collectively on a shared idea, since the "paintings that ought to be made . . . exceed the power of an isolated individual." Included in this letter is a sketch of a still life with a blue enameled coffeepot. Bernard would have recognized it as an homage to his own painting made six months earlier while the two artists were in Paris. The sketch of the street in Saintes-Maries documents his freshly painted canvas, with copious notations of the pairs of complementary colors he employed.

Upon his return from an intensely productive journey to the seaside town of Saintes-Maries, van Gogh sent this letter with a sheet of sketches enclosed to Bernard. The care he took with the drawings shows that he was eager to communicate the excitement of his work resulting from the trip. Inspired by the vibrant and constantly changing colors of the Mediterrenean, he described the beached fishing boats as being "so pretty in shape and color that one thought of flowers." He included a quick sketch of the boats along with outlines of another seascape, and two landscapes he was working on. In the letter he continued to discuss his theories about color and the use of black and white, adding a sketch of a woman in a black and white checked dress to emphasize the need to use such pigments boldly. He then jotted down a small sketch of one of the local cottages that became the subject for several drawings and paintings.