Fountains Abbey Bestiary

The wondrous creatures of the bestiary inspired delight and fascination by mixing the familiar with the strange, the local with the distant, and the dangerous with the desirable. The animals are presented in the manner of an encyclopedia. Generally, each entry provides a physical description of the creature, followed by notes on its location, habitat, behaviors, and its allegorical significance. Bestiaries were meant to reveal to medieval Christians the wonder of creation and the hidden meanings they believed were built by God into the natural world.

Fountains Abbey bestiary

England, probably North Yorkshire, ca. 1325–1350.

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

MS M.890

Thumbnails

MS M.890, front cover

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

MS M.890, inside front cover–front flyleaf 1r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

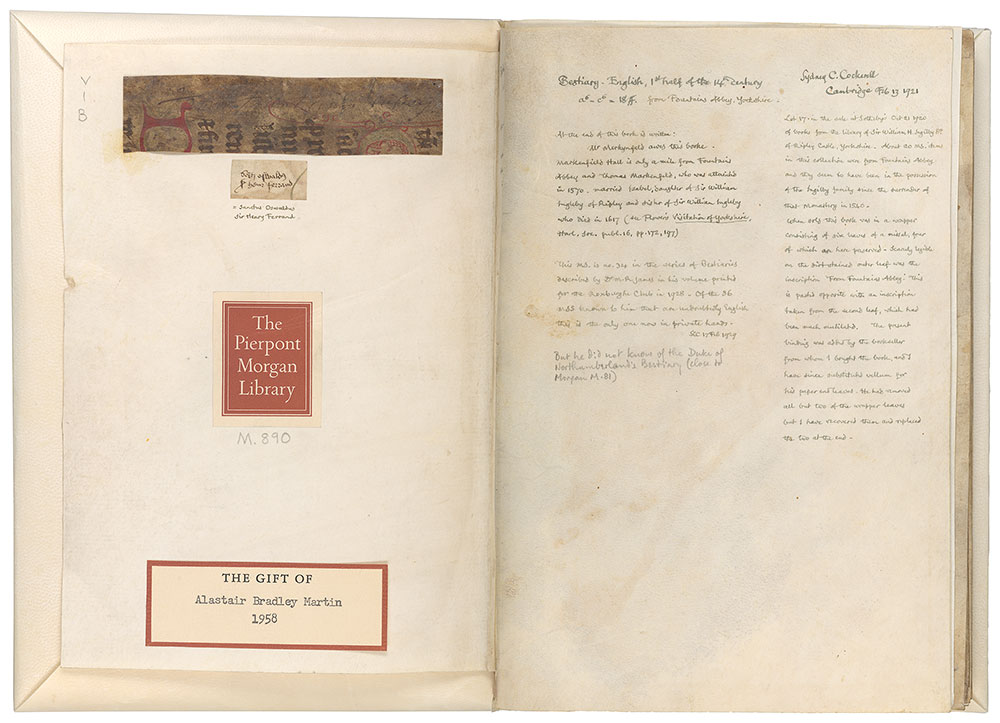

MS M.890, front flyleaf 1v–2r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

MS M.890, front flyleaf 2v–3r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

MS M.890, front flyleaf 3v–4r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

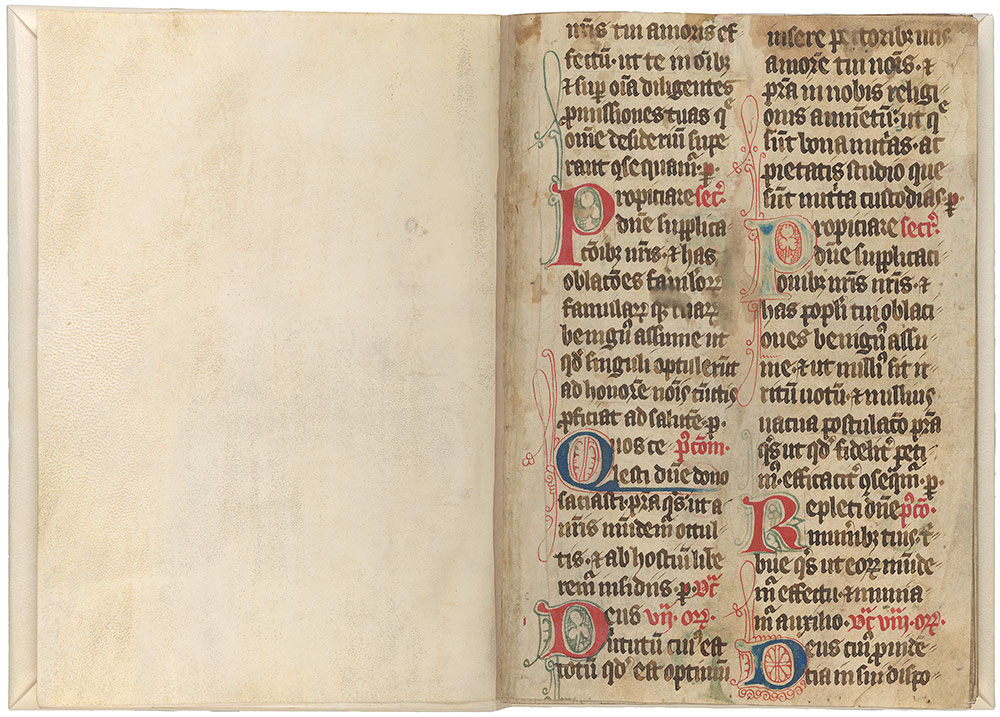

MS M.890, front flyleaf 4v–fol [i]r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

MS M.890, fols. [i]v–1r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

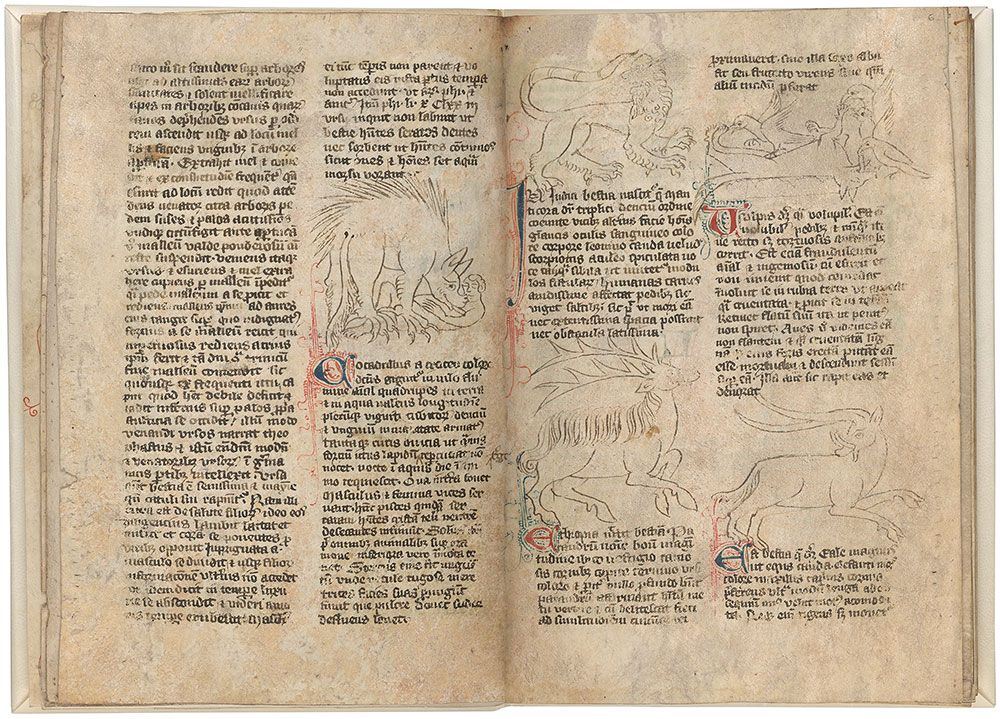

Right Page (Fol. 1r)

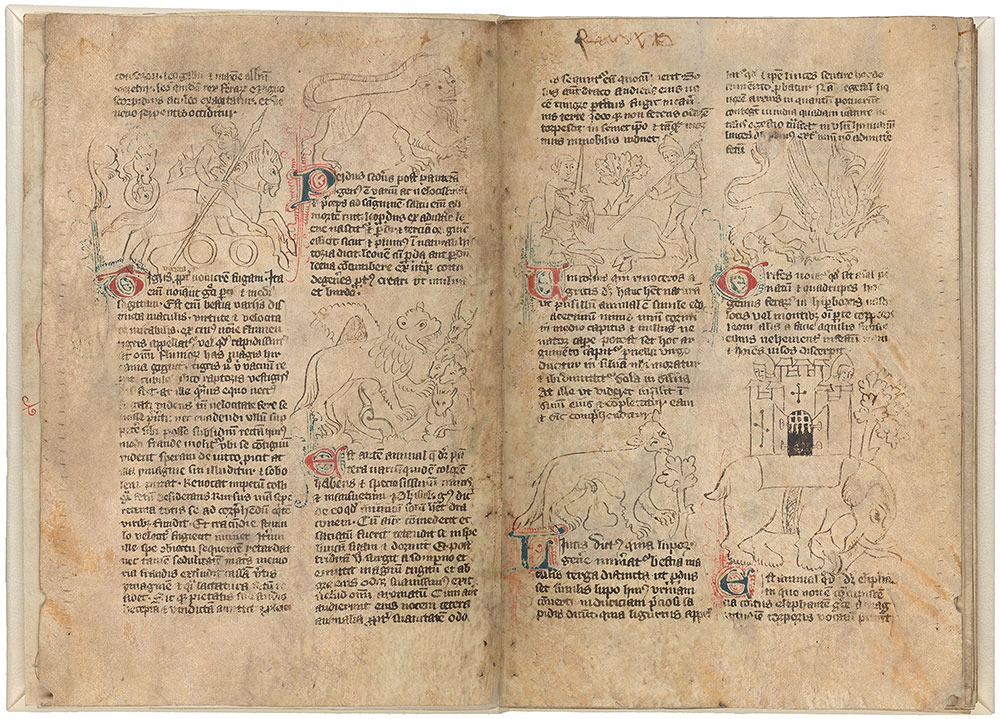

Lion 1: The flame-like fur of this lion’s mane differs from the curly manes of the other lions on the folio; according to the text, a straight mane is a sign of a lion’s ferocity, on full display here as the maneater sinks its teeth into its victim.

Lion 2: The lion was a type for Christ, because lion cubs were thought to be stillborn for three days before the male lion breathes life into its cubs, as shown here.

Lion 3: Here a lion is shown demonstrating its awful roar, so terrifying that it paralyzed its enemies with fright.

Lion 4: This lion’s heraldic stance (passant guardant) represents the lion’s status as king of beasts and contributes to the aristocratic character of the manuscript.

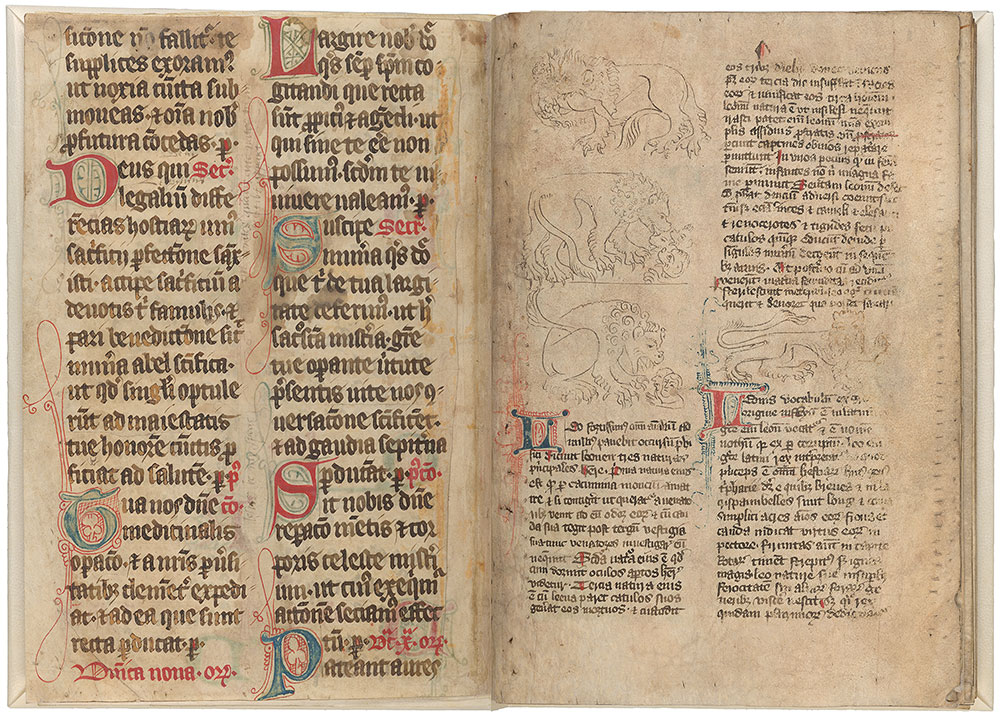

MS M.890, fols. 1v–2r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 1v)

Tiger: A hunter uses a mirror to distract a tiger while he steals away her two cubs.

Pard: A pard—a fierce mythical feline with a mottled coat—is depicted here with a humanoid face and beard.

Panther: The charismatic panther attracts animals with its fragrant breath.

Right Page (Fol. 2r)

Unicorn: A unicorn is lured by a maiden to her lap so that a male hunter can drive his spear through its flank.

Lynx: A lynx makes a puddle of urine, which was believed to harden into a precious stone.

Griffin: A griffin—part lion, part eagle—strikes a heraldic pose.

Elephant: A war elephant, which the text tells us is as big as a mountain, bears on its back a European-style crenelated castle guarded by two soldiers.

MS M.890, fols. 2v–3r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 2v)

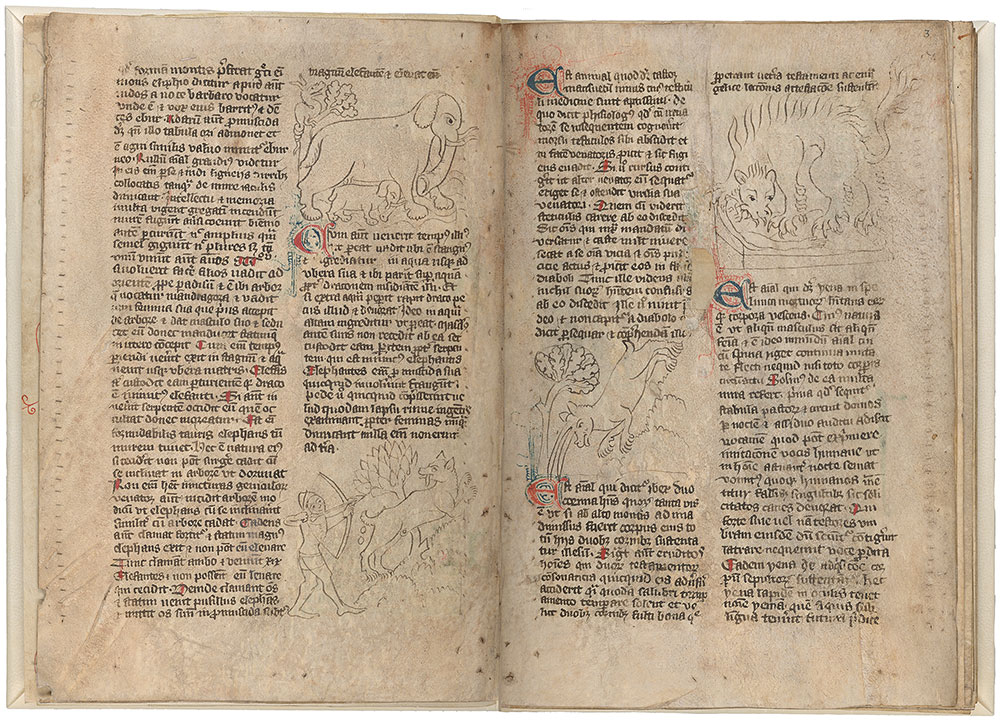

Elephant: A father elephant protects its offspring from the beast’s age-old enemy seen lurking in the tree: the dragon.

Beaver: Hunted for the curative properties of its testicles, a beaver is shown sacrificing its organs in an attempt to escape capture.

Right Page (Fol. 3r)

Ibex: The shock-resistant ibex breaks its headlong fall with its powerful horns.

Hyena: The hyena is reputed to feed on the flesh of the dead. The passage on the hyena is one of many anti-Jewish barbs in the medieval bestiary.

MS M.890, fols. 3v–4r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 3v)

Bonnacon: The legendary bonnacon, shown here as a curly-horned bull, was thought to defend itself from hunters with a blast of caustic feces.

Ape: At the top of the second column, a hunter pursues a female ape and her twin offspring. Under pressure, she will drop the infant she is cradling, while the less favored one—equated with sin—clings to her back.

Satyr: The bestiary classifies the satyr—shown here as a naked, bearded man with long, curled tail holding its club—as a type of ape.

Right Page (Fol. 4r)

Stag: The stag here may be leaping as described in the text, which also notes that its right horn is best for medicinal purposes.

Goats: A shepherd rests while one of his goats stands on hind legs to feed from a tree. Goats that graze in ever higher pastures were a metaphor for Christians who graze on the law of the Lord and rise from one virtue to another.

MS M.890, fols. 4v–5r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 4v)

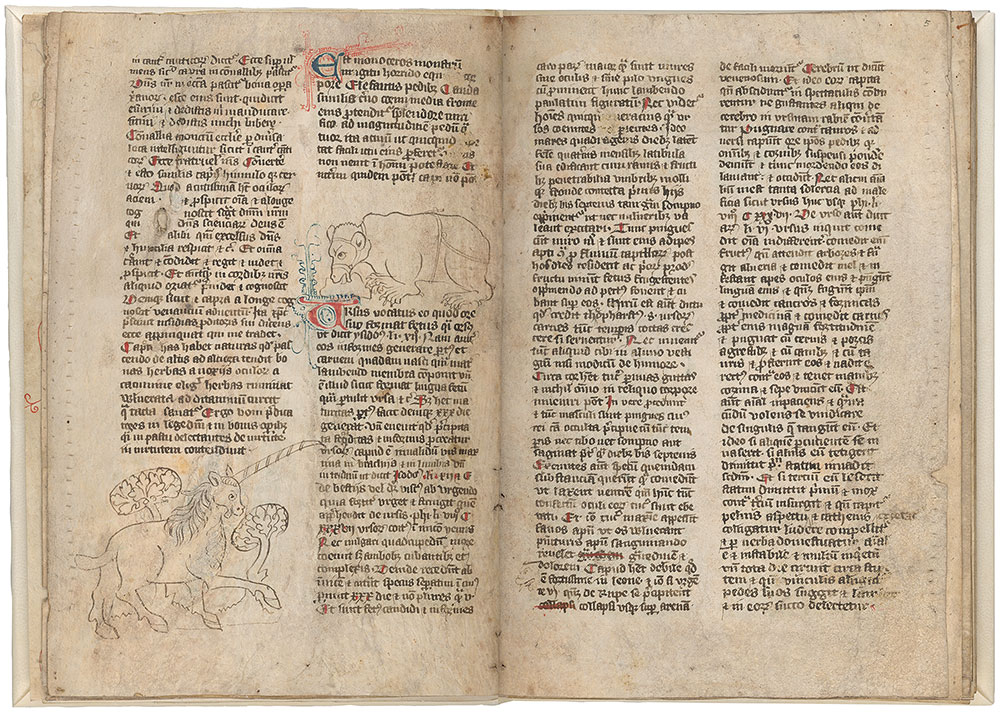

Monoceros: This equine unicorn does not quite match its description, which calls it a monster with the body of a horse, feet of an elephant, and tail of a deer.

Bear: A mother bear wearing a harness is shown tending to her newborn offspring; bear cubs were thought to be born unformed until their mother licked them into shape.

MS M.890, fols. 5v–6r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 5v)

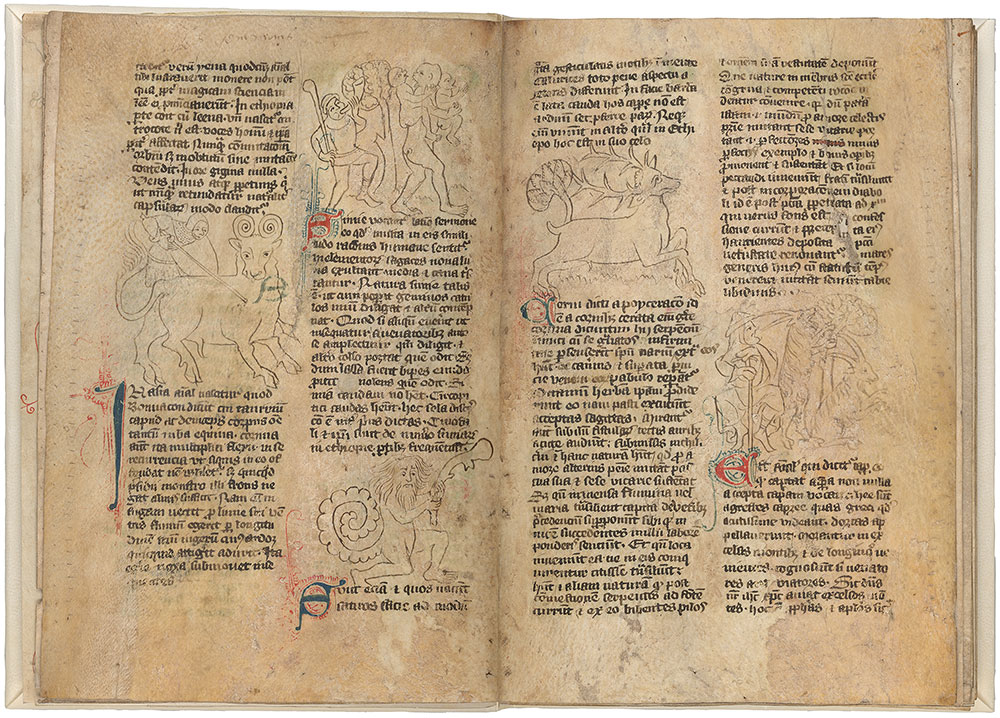

Crocodile: A hulking, furry, man-eating beast meant to represent a crocodile hunches over its victim. Crocodiles were thought to shed tears over their prey and were thus considered a symbol of hypocrisy.

Right Page (Fol. 6r)

Manticore: A deadly manticore—which has the head of a man, the body of a lion, and the segmented tail of a scorpion—was often associated with Jews; in bestiaries its facial features might embody ugly anti-Jewish stereotypes.

Parandrus: The longhaired and prancing parandrus is said to live in Ethiopia.

Fox: A fox plays dead, its tongue hanging from its mouth, to lure crows into its devouring jaws.

Yale: The fierce yale was thought to be able to move its dangerous horns independently.

MS M.890, fols. 6v–7r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

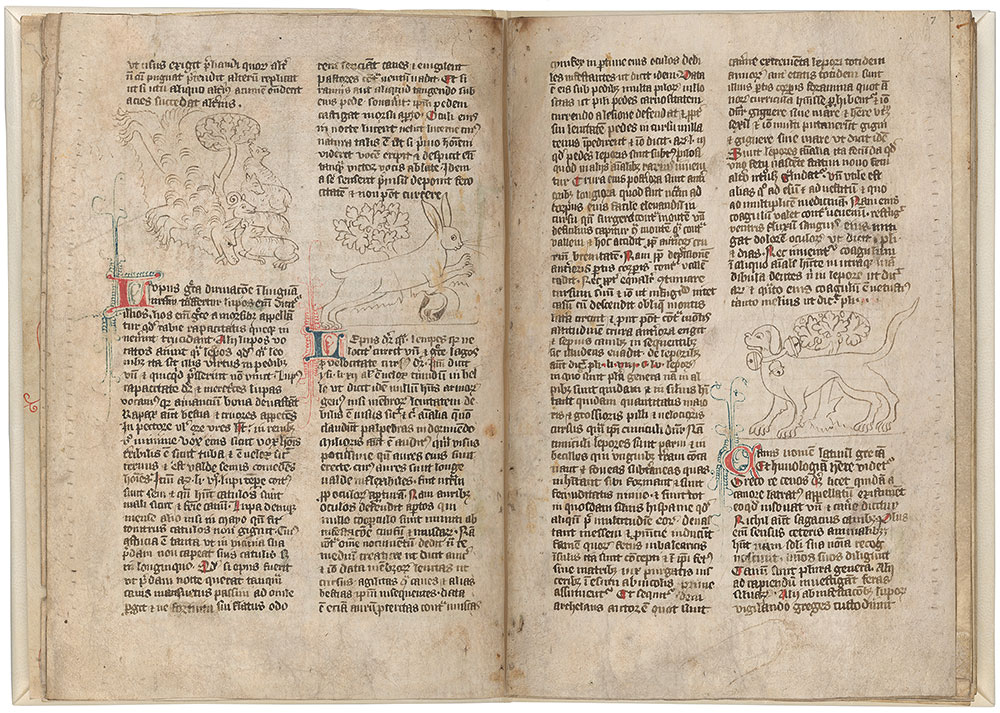

Left Page (Fol. 6v)

Wolf: A wolf pounces on an unsuspecting flock of sheep, signifying allegorically that the faithful are stalked by the devil.

Hare: A hare—whose principle trait is timidity—follows a companion into a burrow at the base of a tree.

Right Page (Fol. 7r)

Dog 1: The dog, representing loyalty, is shown wearing one of the fashionable belled collars described in some aristocratic inventories.

MS M.890, fols. 7v–8r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

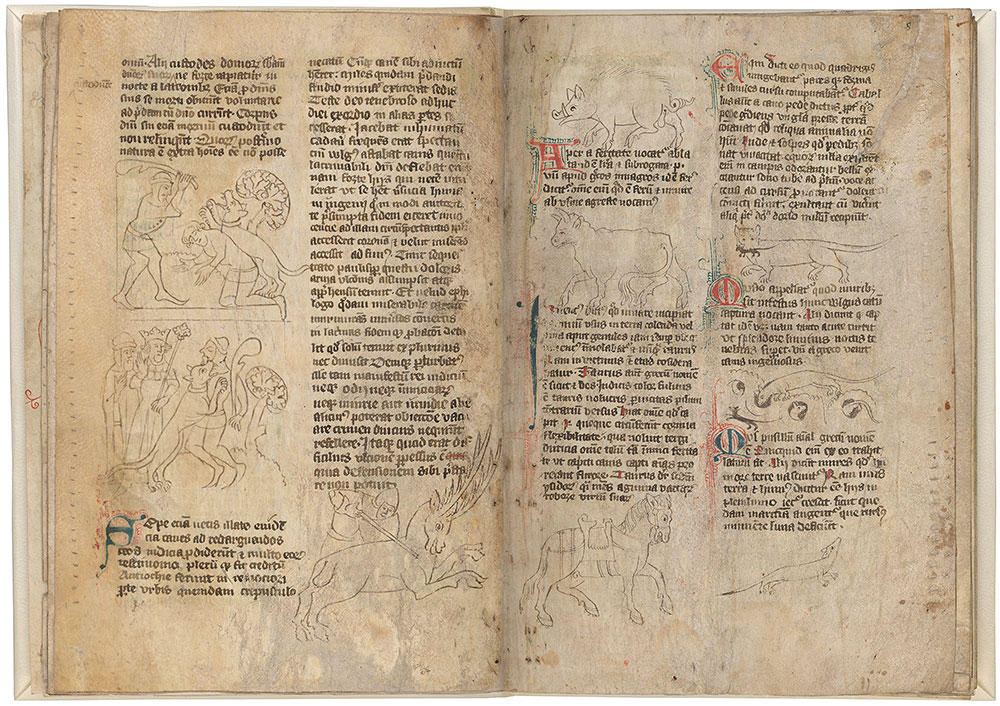

Left Page (Fol. 7v)

Dog 2: In these two scenes a faithful dog is first shown trying to save his master from an attacker, and next identifying the murderer before the king.

Stag: The text about deer is missing from this bestiary, even though the illustrator includes an intriguing drawing of a hunter taking down an impressive 11-pointed stag.

Right Page (Fol. 8r)

Boar: This curly-tailed boar illustrates a short passage informing us that the animal was named for its wildness.

Bullock: According to the text, certain young bulls, such as the Indian Bullock, are not only agile but have thick hides which make them impervious to injury.

Horse: According to the text this stallion, shown with teeth bared, can smell war. The details of the caparison, horseshoes, and saddle refer to the absent rider, to whom horses are said to have been fiercely loyal.

Cat: A cat with a recently captured mouse in its mouth demonstrates the effectiveness of its keen eyesight, which brings the skillful hunter success at night as well as in daytime.

Mouse: Mice running through underground tunnels illustrate the text, which informs us that the rodents are born from the soil and live in the soil.

Weasel: The weasel walking with its nose pointed upwards may be seeking its lost offspring; if they are able to find them, the text tells us, weasels are able to revive them from the dead.

MS M.890, fols. 8v–9r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

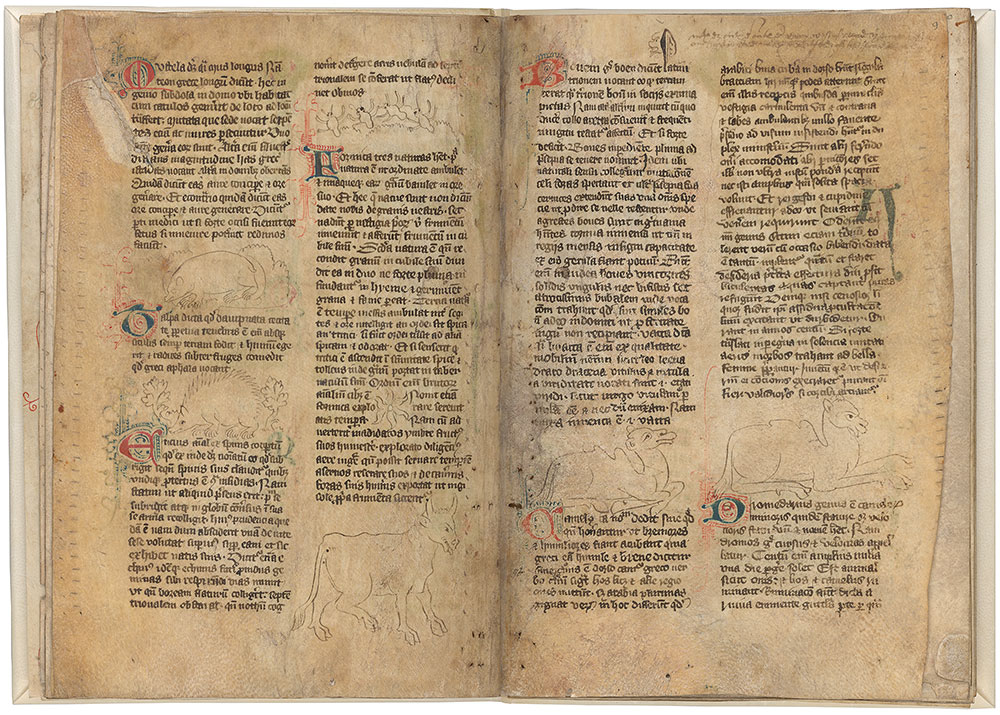

Left Page (Fol. 8v)

Mole: The pupil-less eyes of this mole draw attention to the creature’s blindness, emphasized in the bestiary description.

Hedgehog: A hedgehog crouches between two vines, perhaps looking to salvage grapes that the bestiary tells us they speared on their quills and transported home to their young.

Ants: A line of ants marches forward in unison, an example of cooperation and diligence.

Ox: This ox’s neck, tightly roped with muscle, reveals its time behind the plow as a beast of burden. The text alludes to more monstrous variations of the familiar animal, from the massive wild oxen of Germany, to the single-horned, horse-hooved oxen of India.

Right Page (Fol. 9r)

Camel: This drawing shows a camel at rest from the extraordinary feats of endurance such as traveling for days without water, bearing heavy burdens, and taking part in battles.

Dromedary: Although the text makes a point of distinguishing dromedaries from camels (e.g. by size, and by number of humps, speed), the two beasts on this folio look quite similar.

MS M.890, fols. 9v–10r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

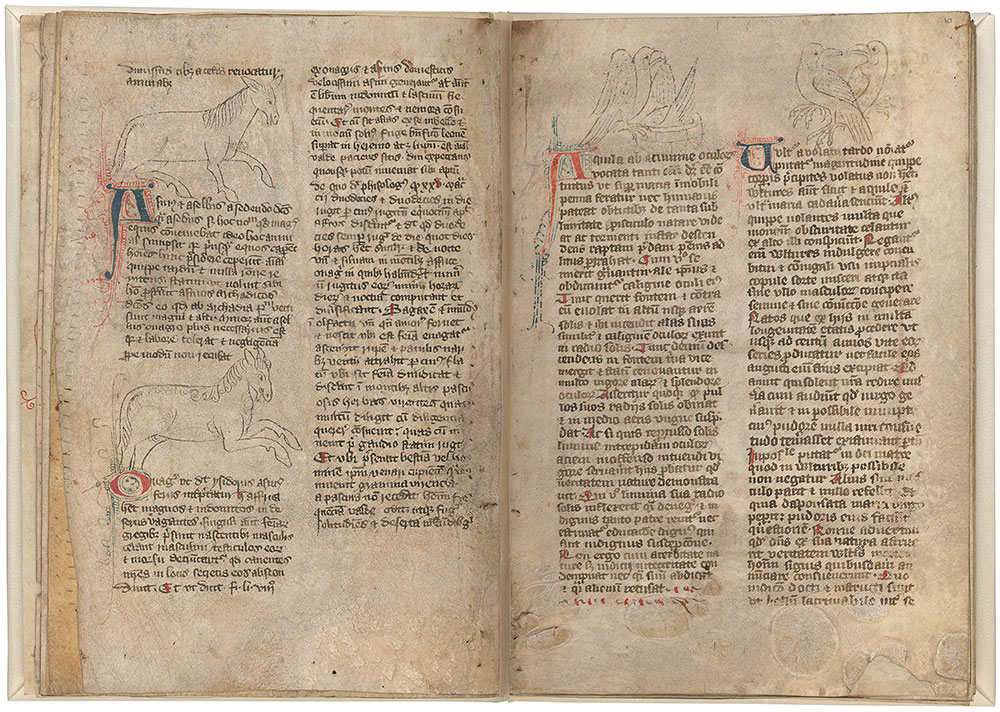

Left Page (Fol. 9v)

Ass: The familiar ass, described as a hardworking, yet obstinate animal, is depicted with naturalistic details, including large ears and pointed fetlocks.

Wild Ass: Unlike the tame ass depicted on the same folio, the wild ass rears aggressively. The bestiary connects its hungry braying at the equinox to the Devil’s ravenous search for souls.

Right Page (Fol. 10r)

Eagle: An aging eagle flies toward the sun before bathing in a fountain three times —a ritual thought to rejuvenate the eyes and wings of the majestic birds, and which symbolizes the powers of baptism.

Vulture : These birds are shown back to back because vultures were thought to reproduce in the absence of copulation (parthenogenesis).

MS M.890, fols. 10v–11r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

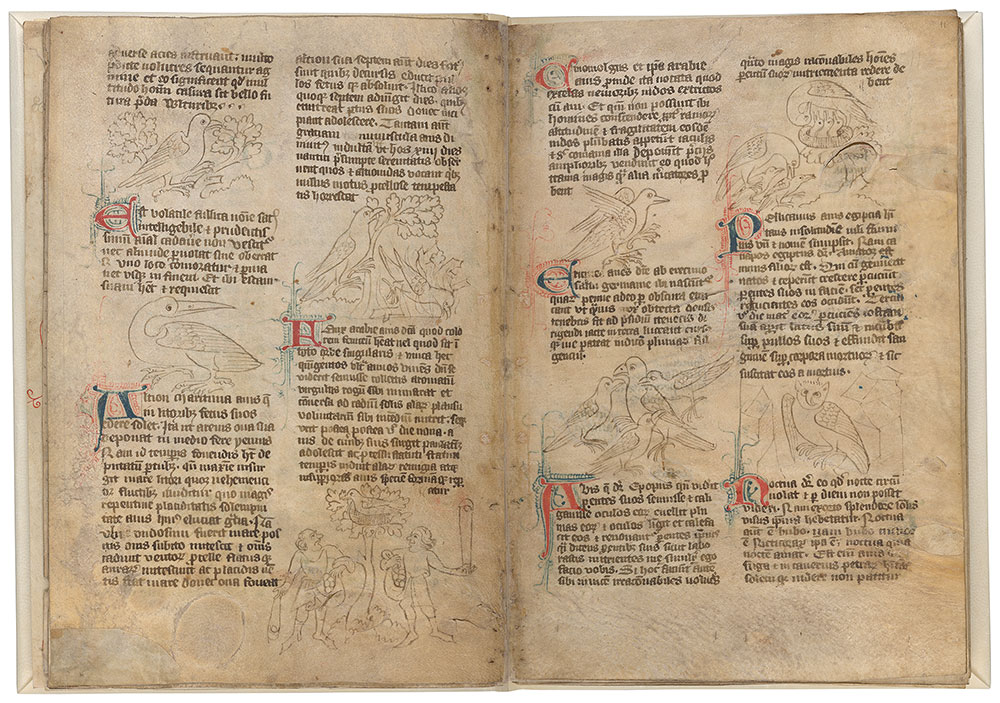

Left Page (Fol. 10v)

Coot: The coot, shown here perched on a tree branch, was praised for living in one spot all its days—a model of constancy to faithful Christians who were not stray from the Church.

Halcyon: The mythical halcyon shown here looking over its shoulder, was thought to cause the sea to quiet in order to hatch and rear its young— a calm period sailors called “halcyon days.”

Phoenix: The legendary phoenix is shown twice: gathering twigs for its funeral pyre, and bursting into rejuvenating flames. Christians saw the bird’s eventual rise from the ashes as an analogy to the Death and Resurrection of Christ.

Cinnamon Bird: A cinnamon bird nests in the fragrant tree after which it is named, while two men below ready their slingshots in order to try to dislodge some of the precious bark.

Right Page (Fol. 11r)

Ercinea: The Ercinea (waxwing) lifts one of its wings as if about to fly; it was thought to have luminous feathers to guide night flights.

Hoopoes: One of two depictions of hoopoes in the manuscript, this image shows three young hoopoes trying to restore life to their parents by licking their old eyes and plucking out aged plumage.

Pelican: This drawing shows two scenes illustrating the mother pelican as a type for Christ: in the first, she kills two of her chicks after they attack her; in the second, she revives them by piercing her breast and feeding them her own blood.

Night owl: A night owl gazes at the viewer with large attentive eyes, which enable the creature to see in the dark.

MS M.890, fols. 11v–12r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 11v)

Siren:

This half-nude siren—part maiden, part bird, and part fish—is shown singing. Sirens were thought to lull sailors to sleep with their sweet voices before tearing them to pieces with their talons.

Partridge: These scenes illustrate two beliefs about partridges conveyed in the bestiary: that it is a deceitful creature, which pillages the eggs of other birds and raises the chicks as its own; and that the males engage in homosexual practices, indicated here by showing the birds back to back.

Crane: According to the text, cranes travel in a military formation and work as a unit to protect one another at night, keeping watch in rotations. As illustrated here, these birds were thought to eat sand or gather small stones as ballast to counter strong winds.

Right Page (Fol. 12r)

Parrot:

The bestiary tells us that parrots are green birds from India with red neck-rings (visible in the drawing), a hard beak, and a skull so thick that you have to use an iron rod to teach it the language of men.

Caladrius: The caladrius is a pure white bird associated with God and found in the courts of kings. An invalid will die if the caladrius turns away from him, but if, as here, the bird looks directly at him, he will live: the bird will absorb his illness and take it to the sun to be burned, leaving the man healed.

MS M.890, fols. 12v–13r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

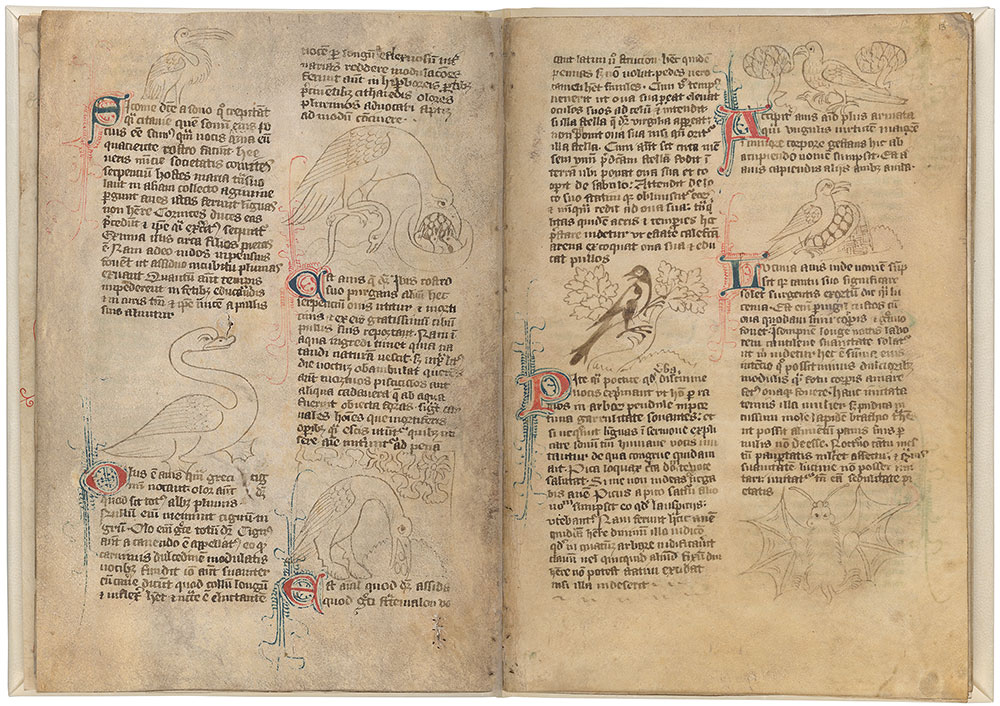

Left Page (Fol. 12v)

Stork: This drawing of a stork emphasizes the elongated beak that gives the bird its Latin name, ciconia: the loud clattering of its bill was thought to resemble chirping crickets (cicaniae).

Swan: The bestiary emphasizes the swan’s long curved neck, which enables its poignant song, but which is also a source of sinful pride.

Ibis: The ibis clenches a snake whose eggs it feeds to its chicks. Because it was thought to feed on snake eggs and carrion from the shore rather than enter the water, it signified carnal men who feed on sin, rather than redeeming themselves through baptismal waters.

Ostrich: The ostrich, shown with the hooves of a camel as described in the text, is burying its eggs in the sand. The bird was seen as an anti-model for the Christian faithful: a hypocrite so preoccupied with earthly distractions that it neglects its young.

Right Page (Fol. 13r)

Magpie: The black and white magpie shown with its beak open was known to imitate human speech; the bestiary both compares it to poets and it criticizes it for its rude chattering.

Hawk: The hawk is depicted clutching its prey in its talons. Accipiter, the Latin name for a hawk, means “taker,” which describes the hawk’s eagerness to snatch its prey.

Nightingale: The nightingale watches over her eggs, nestled close to her breast. The bestiary compares her maternal devotion to the virtuous woman who tirelessly provides for her children.

Bat: Although included with the birds, the bestiary notes that the bat, shown with membranous wings outstretched, gives birth to live young and eats with teeth, not a beak.

MS M.890, fols. 13v–14r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

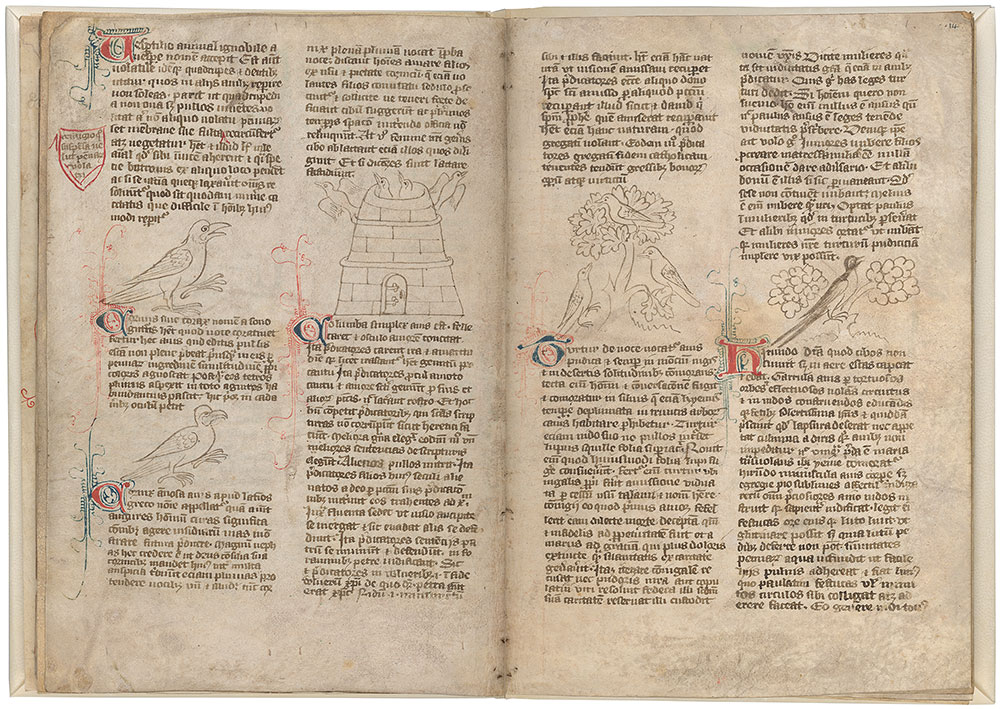

Left Page (Fol. 13v)

Raven: The bestiary tells us that the raven’s Latin name, corvus, comes from the croaking sound it makes; it also notes that the carrion-eater starts with the eyes when feeding on corpses.

Crow: The bestiary depicts the crow as similar in appearance but slightly smaller than the raven illustrated above it. It encourages men to emulate the crow in the attentive and equitable way it was thought to care for its offspring.

Dove: The bestiary pictures multiple birds in a dovecote to convey the importance of their flying in flocks—holding together like good preachers hold together the faithful through virtue and good works.

Right Page (Fol. 14r)

Turtledove: The bestiary praises the constancy of the female turtledove, perhaps shown perched alone atop the tree as a chaste “widow” after her mate’s death.

Swallow: The long-tailed swallow was admired for its ability to catch and eat its prey while airborne, its skill in nest building, and its reputed ability to restore sight to its blind offspring.

MS M.890, fols. 14v–15r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

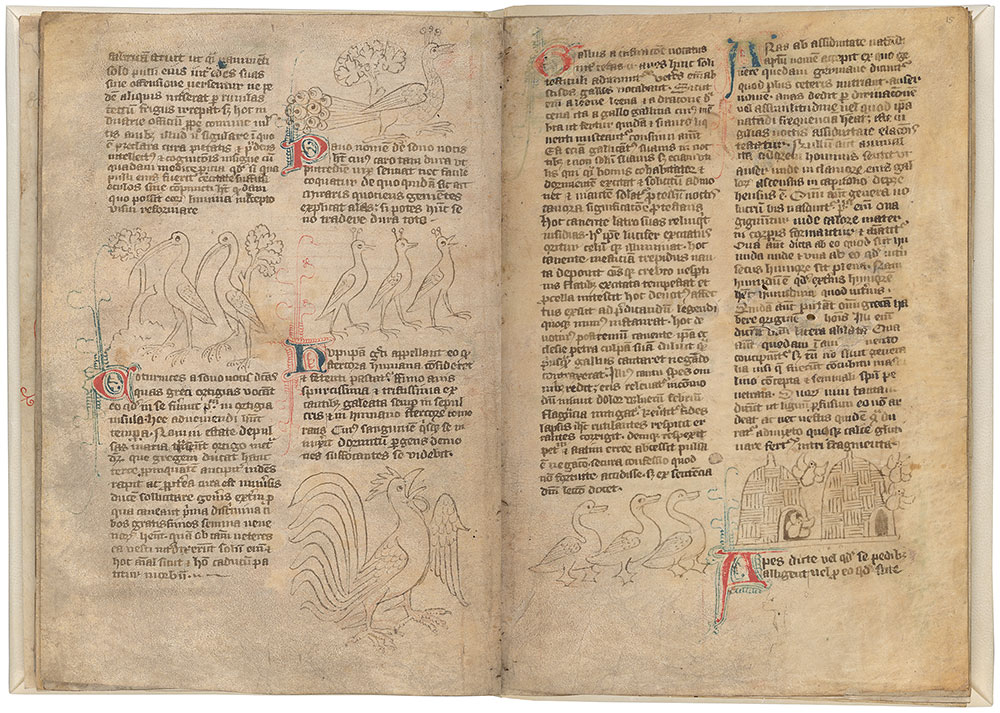

Left Page (Fol. 14v)

Quail: The birds shown here are supposed to be quails—perhaps the length of their beaks are exaggerated to emphasize their reported habit of foraging for and consuming poisonous seeds. The quail was believed to be the only creature other than man to experience “falling sickness” (epilepsy).

Peacock: The text comments on the gem-like beauty of the peacock’s feathers, as well as its hard and difficult-to-cook flesh. It quotes from Martial’s Epigrams: “You are lost in admiration, whenever it spreads its jeweled wings; can you consign it, hard-hearted woman, to the unfeeling cook?” (xiii, 70).

Hoopoes: These birds, with “prominent crests” are hoopoes making their second appearance in the manuscript. The text tells us that they feed on human excrement, and that if you rub yourself with the blood of a hoopoe on your way to bed, you will dream of demons trying to suffocate you.

Cock: The open beak of this cock appears to have been scratched out and redrawn at a wider angle, likely to emphasize that it is in the act of crowing. The text likens the cockcrow to “the words of Jesus” announcing the end of night and bringing hope.

Right Page (Fol. 15r)

Ducks: These cheerful ducks illustrate an entry explaining that the word “duck” in Latin (anas) is connected to the fact that they are constantly swimming (natare).

Bees: Categorized as birds, the giant bees shown here were presented to medieval readers as exemplary animals that worked hard for the benefit of community and king.

MS M.890, fols. 15v–16r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

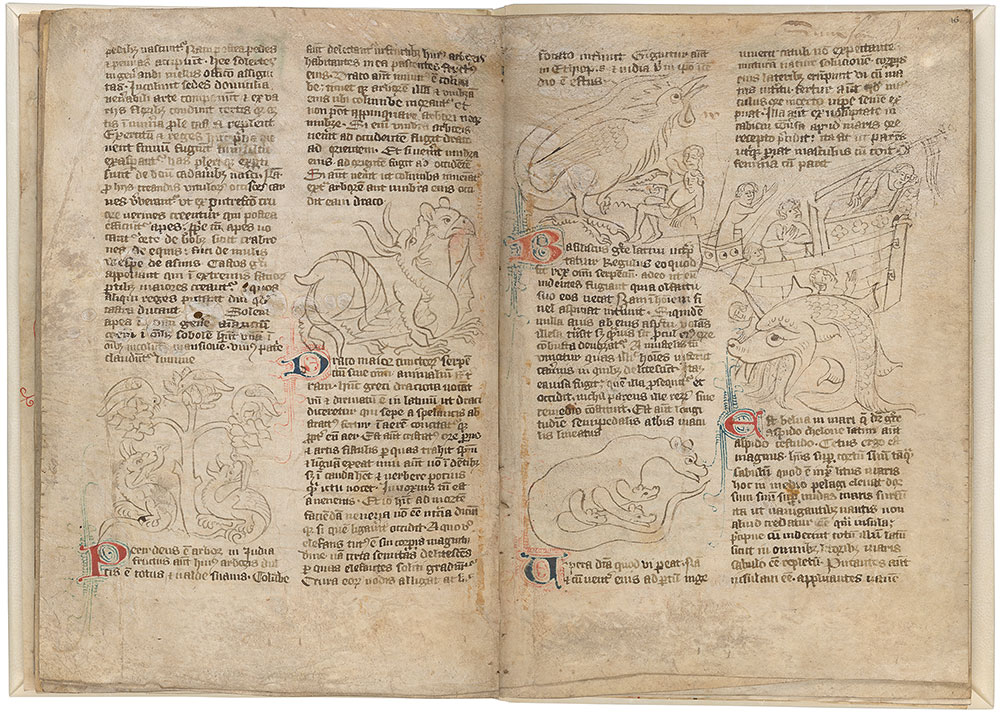

Left Page (Fol. 15v)

The Perindens Tree: The perindens tree, thought to grow in India, was thought to serve as a haven for doves, who are safe from marauding dragons shown devouring those who have strayed from its protective branches. The perindens tree was seen as an allegory of Christianity: the tree was God sheltering the faithful Christians (the doves) from the devil (the dragons).

Dragon: The text describes how even the elephant’s huge size cannot save it from the dragon, “the most monstrous serpent of all,” which is equated with the devil. It is not clear why this elephant is shown with round upright ears and a beak, especially since more recognizable examples are depicted elsewhere in the manuscript (fols. 2r-v).

Right Page (Fol. 16r)

Basilisk: The basilisk, a winged snake with the head of a cock, hovers over two men who are likely dead. The basilisk kills by scent alone and can paralyze its prey with a glance.

Viper: A viper gives birth at the bottom left, its young bursting forth from its side. This was thought to be the origin of its name, as it gave birth by force (vi pariat).

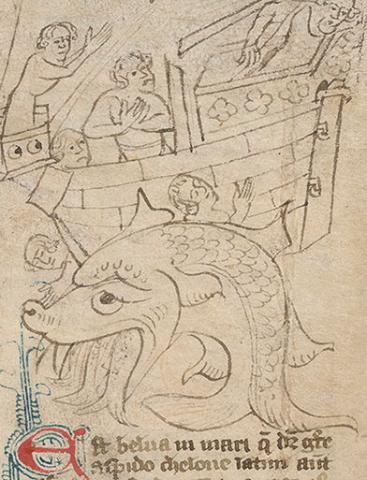

Aspidochelone: The legendary aspidochelone, a great whale or sea turtle, was so huge that when it rose from the sea, sailors would land on it, mistaking it for an island. They would meet their doom when the great sea creature descended into the deeps — an example of those who are drawn in to trust the Devil, and are in turn undone.

MS M.890, fols. 16v–17r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

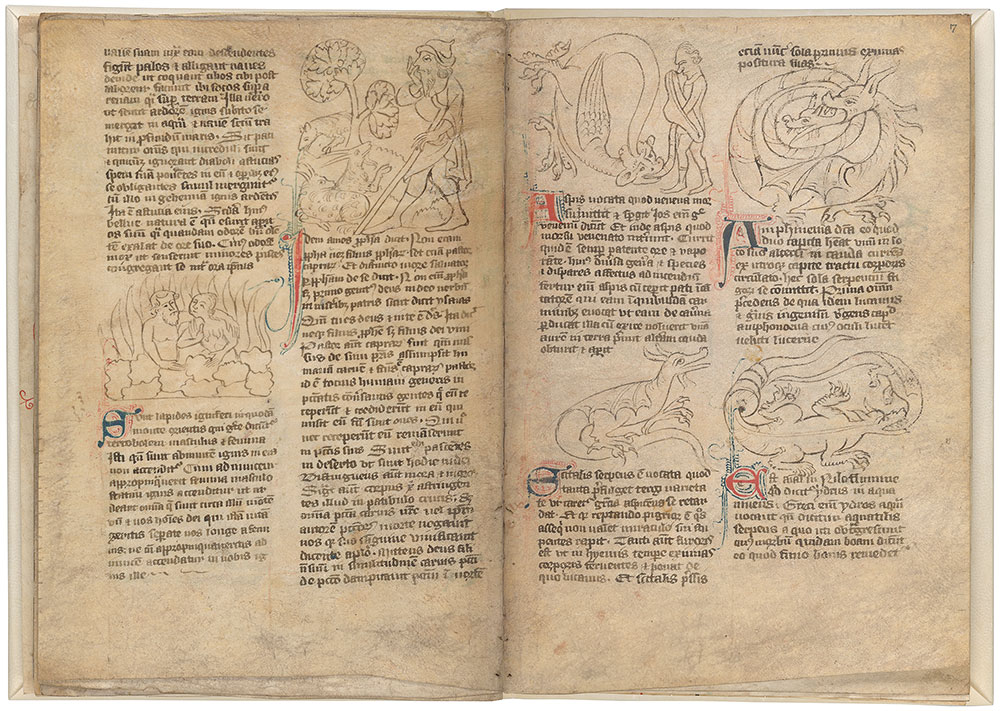

Left Page (Fol. 16v)

Fire Stones: This is a drawing of personified “fire stones”: gendered stones that ignited and destroyed everything around them when a female stone came into contact with a male stone. The bestiary treats them as a cautionary tale for the clergy, who were warned to distance themselves from lustful women.

Amos: Here Amos, a shepherd mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, is depicted wearing a Phrygian cap, associated with Jews. This drawing illustrates an anti-Jewish passage—typical of the bestiary—which compares Jews to sinful goats that Christ was unable to convert into sheep.

Right Page (Fol. 17r)

Asp: Typically, the asp plugs its ear with its tail in order to resist the snake-charmer’s musical wiles— but here the snake’s tail rests on top of its head. The snake-charmer holds up a shield to protect himself from the snake’s venomous bite.

Scitalis: The scitalis pictured here does not much look like a snake with its pointed ears, wings, whiskers, and claws: it is said to stun its prey with its marvelous appearance and glittering scales.

Amphisbaena: The two-headed amphisbaena can move quickly with either head in the lead.

Hydrus: The hydrus lubricates itself with mud and slips down the throat of a crocodile in order to kill it from the inside, as Christ coated himself in human skin and defeated the devil.

MS M.890, fols. 17v–18r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

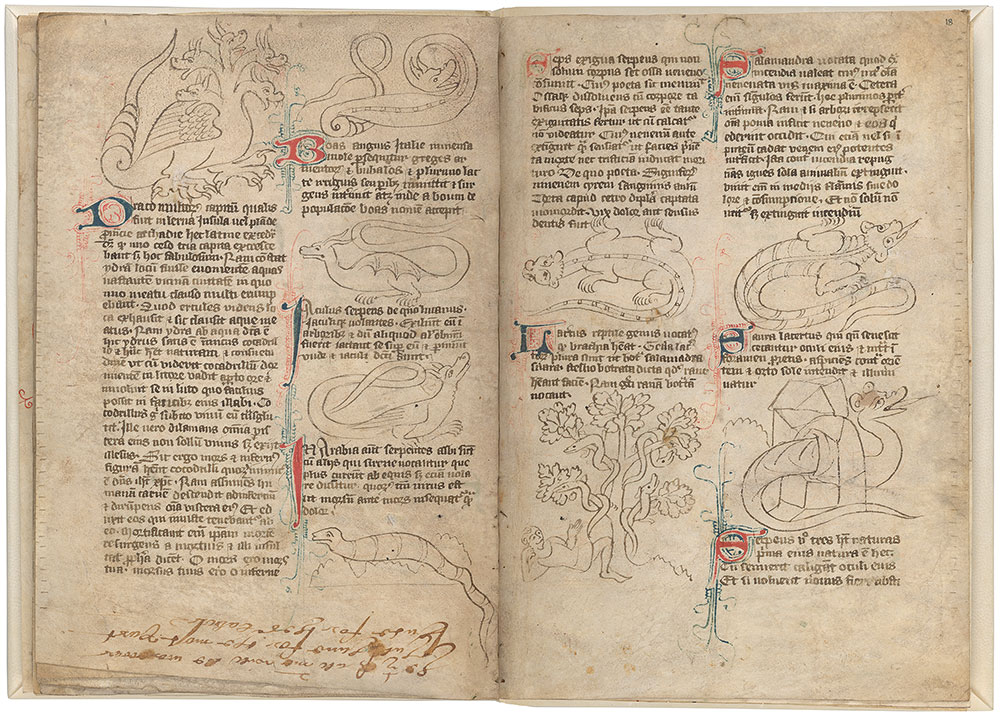

Left Page (Fol. 17v)

The Hydra: The hydra—a snake with regenerating heads that was associated with Hercules—is one animal the bestiary tells us is not real.

Boa: The boa is described as a large Italian snake whose name derived from its supposed habit of attacking cattle. The prominent teeth shown here illustrate the medieval understanding of this snake’s nature: rather than squeezing its victims to death, the boa fastens itself onto cows’ udders and sucks them dry.

Javelin: Though its wings are pictured folded to its sides, the serpent depicted here was thought capable of flying at deadly speeds and thus was called a “javelin.” The bestiary explains that javelins like to hide in trees and launch themselves at their unsuspecting prey below.

Siren: The siren is a serpent thought to inhabit Arabia. White-skinned and capable of flying swifter than a horse, the siren also possesses fast-acting poison that kills its victims before they feel pain.

Seps: The glum-looking wingless serpent at the bottom of the page is a very small snake called a seps, whose venom was reputed to dissolve both flesh and bones (its name is related to the word “septic”). The seps is associated with another venomous serpent called the dipsas, which is so small it cannot be seen when stepped on, and thus is left unpictured.

Right Page (Fol. 18r)

Lizard: Classified as a reptile rather than a serpent because of its four legs, the lizard pictured here may be a botrax, characterized by its frog-like face, or perhaps it is a stellio, also mentioned in the text, and named after the star-like pattern of colorful dots along its back.

Salamander: The bestiary claims that if a salamander creeps into a tree, its venom will infect all the fruit, and may kill anyone who eats it, such as the poisoned victim beneath this infested tree. Salamanders were also legendary for their ability to withstand and even extinguish fire.

Saura: The saura, pictured here, is a type of lizard said to lose its vision with age, but which can cure its blindness by gazing toward the rising sun through a crack in a wall.

The Nature of Serpents: This illustration of a section on the “nature of serpents” visualizes how a snake molts: it sloughs off its skin by scraping its body against the walls of a narrow slit in a rock (or, in this case, a gate) as Christians are urged to slough off their sinful selves with Christ’s help.

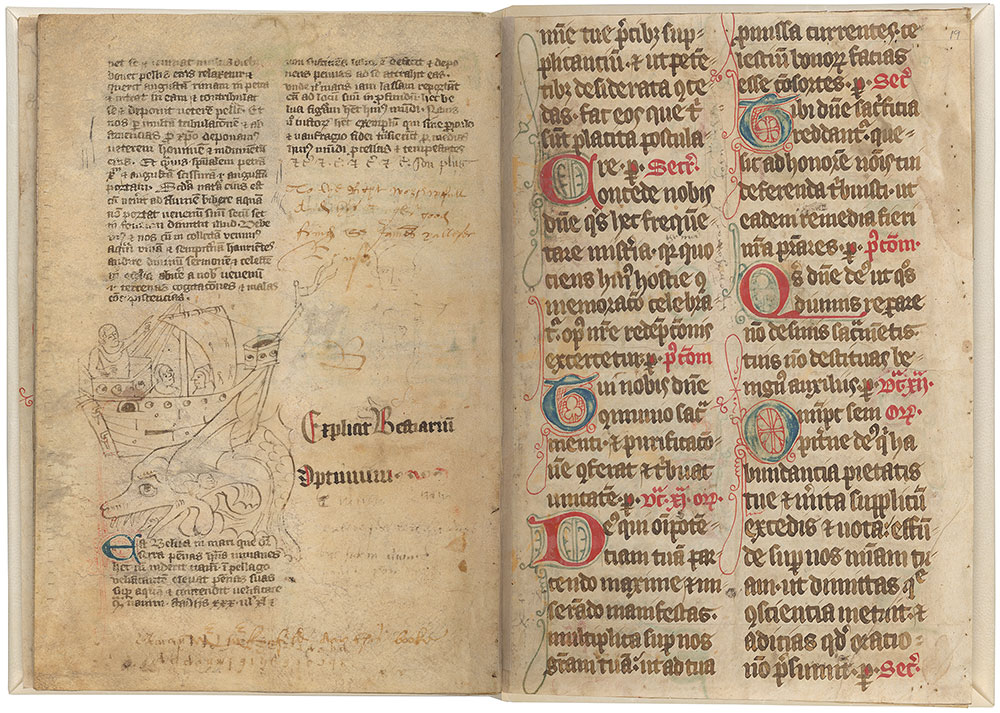

MS M.890, fols. 18v–19r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

Left Page (Fol. 18v)

Sawfish: Here, the legendary flying sawfish lifts its immense wings to race a ship; when it is exhausted, it will retreat to the sea, representing Christians who start in good faith but are conquered by vice.

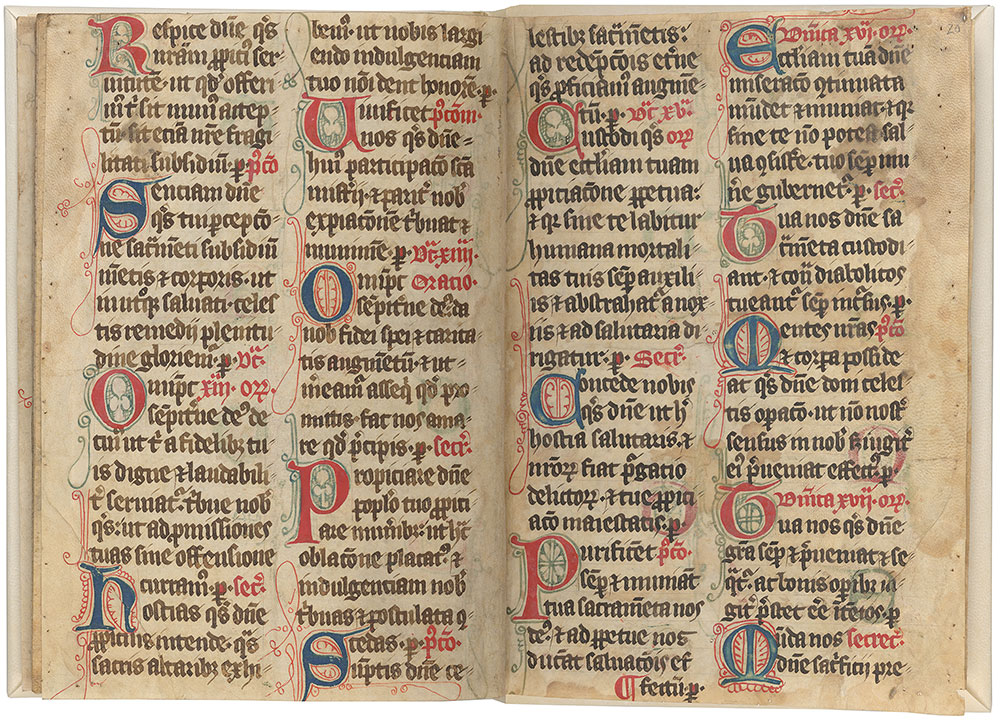

MS M.890, fols. 19v–20r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

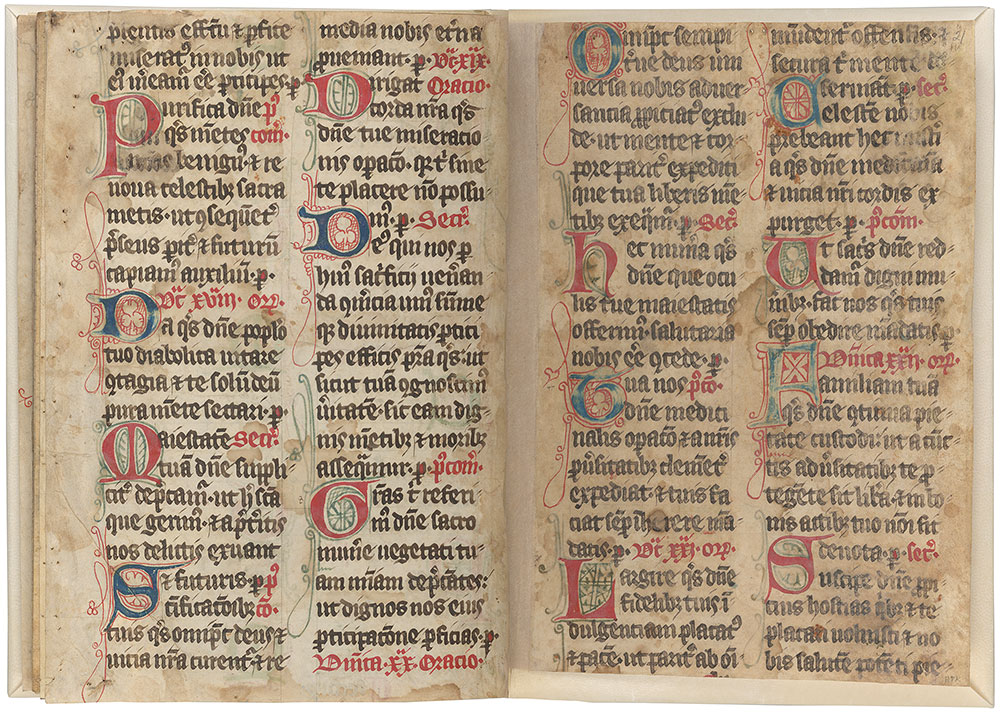

MS M.890, fols. 20v–21r

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

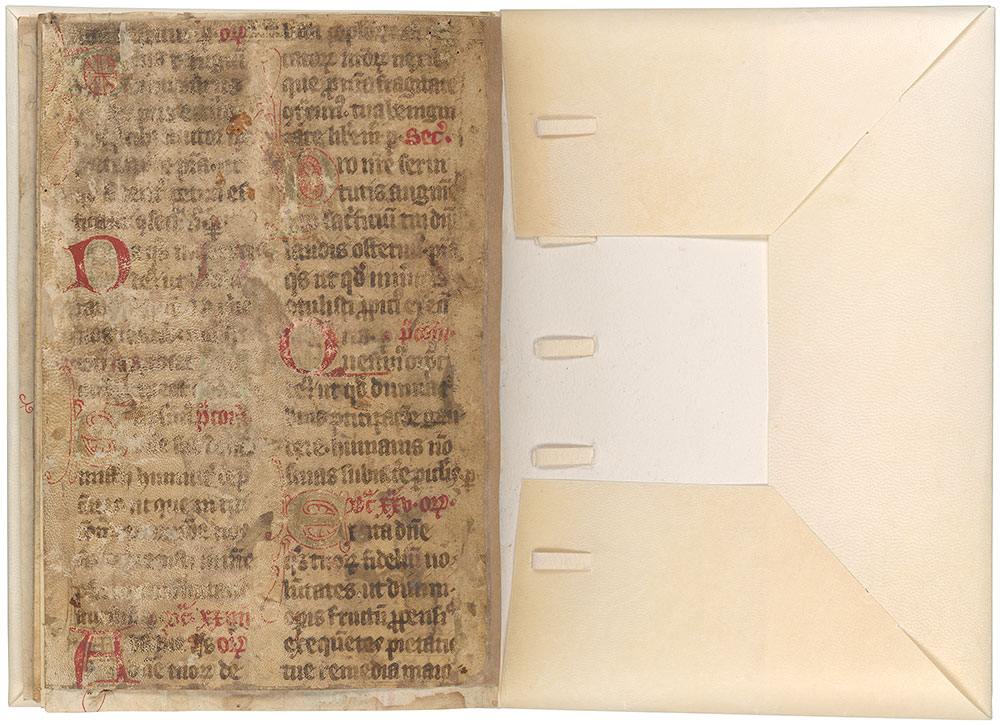

MS M.890, fol. 21v–inside back cover

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

MS M.890, back cover

Fountains Abbey bestiary

Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958