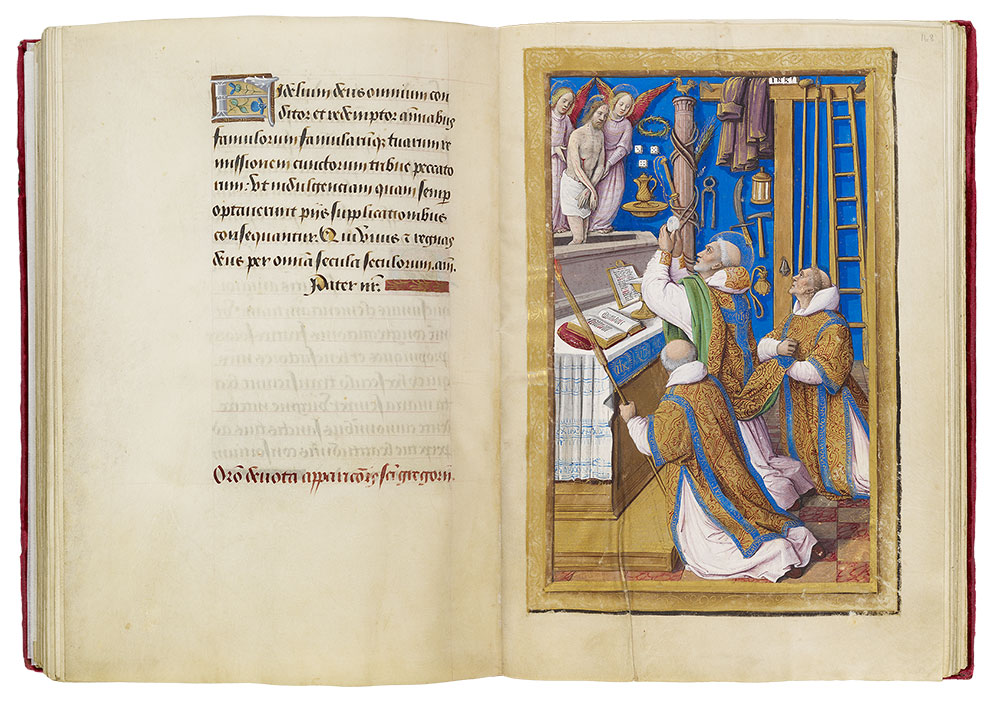

Seven Prayers of St. Gregory, fol. 168r

Mass of St. Gregory

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

Mass of St. Gregory (fol. 168)

The typical illustration for the Seven Prayers of St. Gregory is the so-called Mass of St. Gregory, an image that apparently was invented in the fifteenth century.

Against the blue background are the arma christi (arms of Christ), which were part of the Man of Sorrows iconography.

A pictographic summary of Christ's Passion makes it possible for the devout to contemplate the enormity of Christ's sufferings; the symbols include the purse (Judas's betrayal for thirty pieces of silver), lantern (Christ was taken at night), sword (with which Peter cut off Malchus's ear), ewer and dish (with which Pilate washed his hands of guilt), cock (crowed when Peter denied he was a disciple of Christ), column with rope and two kinds of scourges (Flagellation), purple garment and Crown of Thorns (Mocking of Christ), Cross (Carrying of Cross), hammer and three nails in Cross with titulus (Crucifixion), three dice (soldiers gambled for Christ's garments), spear with sponge (Christ took vinegar), spear (Christ's side opened, with outpouring of blood and water), and pincers and ladder (for the Deposition).

Gregory, holding the wafer (itself decorated with the Crucifixion) between the first finger and thumb of both hands, recites the words Hoc est enim corpus meum (For this is my Body).

St. Gregory, assisted by a deacon and subdeacon, elevates the consecrated Host during a High Mass. As is liturgically correct, the subdeacon holds a torch, while the deacon lifts the back of Gregory's chasuble, which, like the altar frontal, is embroidered with the monogram of Jesus (IHS).

The live and bleeding Christ miraculously appears on the altar, supported by two angels above his sarcophagus.

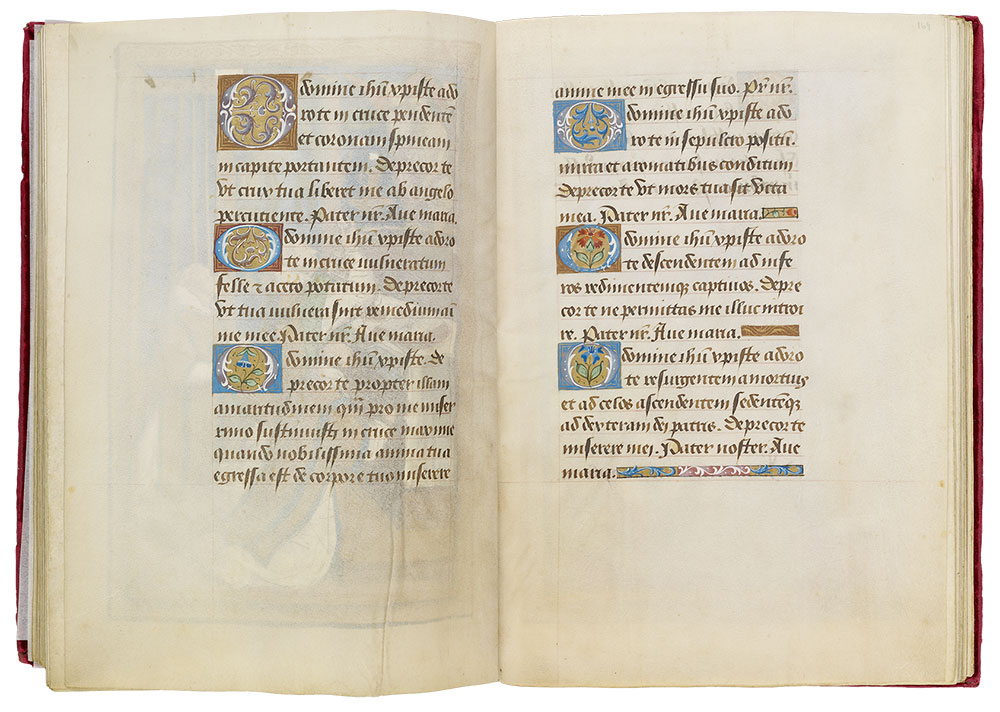

Seven Prayers of St. Gregory (fols. 168v–69v)

As discussed above in connection with the accessory Prayers to the Virgin, in addition to the main texts of Books of Hours, a fairly large number of optional texts and prayers could be included, depending on the piety and pocketbook of the patron. Aside from individual prayers, these could include various Hours (of St. Catherine, of St. John the Baptist, and of the days of the week), special Masses (for saints and the days of the week), and a group of devotions organized around the number seven (Seven Joys of the Virgin, Seven Requests to Our Lord, Seven Last Words of Our Lord, Seven Verses of St. Bernard, and the present Seven Prayers of St. Gregory).

According to tradition the Seven Prayers were written by St. Gregory the Great, the fourth Latin Doctor of the Church (as the rubric for the prayers states in a contemporaneous Rouen Horae also in the Morgan Library's Heineman Collection: MS H.1, fol. 114v). The prayers consist of seven short ejaculations addressed to Christ, each followed by an Our Father and Hail Mary. The first begins:

O Domine Ih[es]u Christi adoro te in cruce pendente[m] et coronam spineam

in capite portantem. Deprecor te ut crux tua liberet me ab angelo percutiente.

(O Lord Jesus Christ, I adore you, hanging on the Cross and wearing the Crown of

Thorns on your head. I beseech you so that your Cross might free me from the

persecuting angel.)

The other six prayers (all beginning "O Domine Ihesu Christi adoro te . . . ") relate to the bleeding Christ, the dying Christ, the Entombment, the Descent into Hell, the Resurrection, and Christ as the Good Shepherd. In the present manuscript the text is preceded by a rubric (fol. 167v) identifying it as a devotional prayer of the Vision of St. Gregory ("Or[ati]o devota apparic[i]o[n]is s[an]c[t]i Gregorii").

Mass of St. Gregory

The initial seed for the story of the Mass of St. Gregory, a ninth-century biography of Gregory, was popularized in the Golden Legend. As Gregory was consecrating the Host during Mass, the woman who baked it laughed in disbelief that her kneaded dough would become the Body of Christ. Instead of giving her communion, he placed the wafer on the altar, praying to God for her unbelief. When the woman saw the host change into a piece of flesh in the form of a finger, she immediately rejoined the faithful; thereafter the flesh again became bread and she took communion. About 1400, however, owing to the growing emphasis fostered by Franciscans on Christ's human suffering—especially in the Meditations on the Life of Christ—the story circulated that the Man of Sorrows himself appeared on the altar. Around the same time a variant story developed to explain the thirteenth-century wonder-working mosaic icon of the Imago pietatis in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome. It was believed to have been commissioned by Gregory himself after, in a Mass, he asked God to change the wine into real blood; in that story Christ appeared on the altar and his blood flowed into the chalice. Indulgences were granted to pilgrims praying before the Santa Croce image, and under Pope Urban VI (r. 137–89), they applied equally to copies of it, which later included prints. Such indulgences were also attached to representations of the Mass of St. Gregory, although none is cited in the present manuscript (a French Horae of about 1485 in Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery, MS W.245, offered, for example, an indulgence of 46,000 years).

MS H.8, fols. 168v–169r

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

MS H.8, fols. 169v–170r

St. Jerome: Jerome in Penance

Hours of Henry VIII

Illuminated by Jean Poyer

Gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

St. Jerome: Jerome in Penance (fol. 170)

As is common in Books of Hours, the final component of the Hours of Henry VIII includes a series of prayers, known as Suffrages, seeking favor from various saints. The well-educated St. Jerome, considered the most learned of the Latin Church fathers, was born around 342 in the small town of Stridon in Dalmatia.

In Antioch St. Jerome decided to retire as a hermit in the Syrian Desert, where he suffered temptations of the flesh. In a letter to his friend Eustachium, he recounted how in the heat of the sun, with no other companions besides scorpions and wild beasts, he imagined Roman maidens dancing before him.

To avoid the temptations of his lascivious imagination, St. Jerome threw himself amid thorn bushes before a crucifix, beat his breast (the rock was a later medieval invention), and fled into the wilderness for four years.

One evening, according to a legend, as Jerome sat within the gates of his monastery, a lion entered, limping in pain. The saint removed a thorn from its paw, tending the lion's wound until it healed. The beast became one of the saint's attributes.

St. Jerome

St. Jerome was sent to Rome as a youth to study the Greek and Latin classics with the pagan grammarian Donatus. Baptized and later ordained as a priest, Jerome made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In 382 he returned to Rome, where he produced the standard text of the Latin Bible (the Vulgate) before moving to Bethlehem, founding a monastic settlement of contemplative hermits with St. Paula (the Hieronymite Order). Although Jerome was never a cardinal (the office did not yet exist), he is depicted as one. Here the cardinal's cloak and hat lie on the ground so we can see his hair shirt. Images of the penitent Jerome in the wilderness originated in Pisa during the late thirteenth/early fourteenth centuries.

St. Jerome Beating His Breast

The motif of the saint beating his breast with a stone—which first occurs in a fourteenth-century panel in Pisa (Galleria San Matteo)—was adopted in the north at the end of the fifteenth century. Scenes of Jerome in the wilderness also afforded the artist an opportunity to explore nature, landscape, and wildlife—features exploited by Poyer. (Feast day: September 30)

Suffrages (fols. 170v–93)

Suffrages, prayers to saints seeking favor or support (also called Memorials), are frequently the last component in a Book of Hours. Petitionary or intercessory in nature, they normally consist of four elements: the first three, an antiphon, versicle, and response, make up a string of praises; the fourth part is a longer prayer (oratio) specifically dealing with some aspect of the saint, along with a request for God's aid through the saint's intercession. Many of these elements are quotations or extractions drawn from the Church's official liturgical texts found in the Breviary, which contained the rounds of offices recited by the clergy during the year, or in the Missal, which contained the Masses. The collect from the Mass and Office (Lauds) of St. Nicholas (6 December), for example, served as the Oratio for his Suffrage (fol. 182v); a translation of the entire suffrage follows.

Antiphon. Nicholas, friend of God, when invested with the episcopal insignia,

showed himself a friend to all.

Versicle. Pray for us, blessed Nicholas.

Response. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

Oratio. O God, you adorned the pious blessed Bishop Nicholas with countless

miracles; grant, we beseech you, that through his merits and prayers, we

may be delivered from the flames of hell. Through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The justification and efficacy of such petitions to the saints had already been established by the fourth century and were unequivocally reaffirmed in the thirteenth century by Thomas Aquinas in his Summa theologica. In raising the question if one should pray to God alone, he referred to Job (5:l), where Eliphaz exhorted him to call upon some of the saints; to show that the saints in heaven could indeed pray for us Aquinas also quoted Jerome: "If the apostles and martyrs while yet in body can pray for others, how much more now that they have the crown of victory and triumph." In asking if prayer to greater saints was more acceptable to God than to lesser saints, Aquinas said it was sometimes more profitable to pray to a lesser saint, since some saints were granted special patronage in certain areas, such as St. Anthony against the fires of hell. Moreover, he added, the effect of prayer depended on one's devotion, and that could be greater for a lesser saint. Aquinas also alluded to another common custom of the Church to support his conclusions, the recitation of the Litany of saints (a practice dating back to the fourth century). It is the celestial hierarchy of saints in the Litany, moreover, that provides the basic ordering of the Suffrages in Books of Hours. Indeed, in the present manuscript, all of the Suffrages are illustrated, forming a kind of pictorial Litany (albeit a very selective one). After the Three Persons of the Trinity comes the Archangel Michael, followed by John the Baptist (our future intercessor at the Last Judgment). Next are the Apostles, male martyrs, confessors (male nonmartyr saints), female martyrs, and widows. The series concludes with All Saints. (It may be of interest to observe that the first five female saints precisely follow the order in which they appear in the manuscript's Litany.) The idea of placing large miniatures of the saints above the Suffrages, with other scenes from the life of the saint in different colored grisailles in the lower borders, brings full circle the page layout of the Calendar and Gospel Lessons at the beginning of the manuscript. The number of Suffrages in Books of Hours can vary greatly, and each is not always illustrated; the series of twenty-four in the present manuscript is particularly rich and bespeaks of a fairly wealthy patron. The placement of Jerome at the beginning of the Suffrages is highly unusual. His position here may have been intended to link Jerome with Pope Gregory, the Church Father who was believed to have written the previous text (Seven Prayers of St. Gregory). In addition, Jerome's Suffrage, as is clear from the translation below, emphasizes his role as a teacher rather than as a penitent.

Antiphon. I shall liken him to a wise man who built his house on rock.

Versicle. The Lord led the just man in right paths.

Response. And showed him the kingdom of God.

Oratio. O God, who didst vouchsafe to provide for thy Church blessed Jerome,

thy confessor, a great doctor for the expounding of the Sacred Scriptures, grant,

we beseech thee, that through his merits we may be enabled, by thine assistance,

to practice what by word and deed he hath taught us. Through Our Lord Jesus

Christ thy Son, who liveth and reigneth, God, with thee, in the unity of the Holy

Spirit, world without end. Amen.

Since the accompanying picture of Jerome in Penance is, like the Mass of Gregory, a full-page miniature (all of the other Suffrages are half-page miniatures with historiated borders), it could be seen as a kind of frontispiece for the Suffrage section. In any case, Jerome and Gregory were both Latin Doctors of the Church, and both miniatures focus on the crucified body of Christ. Codicological evidence and the rubric for the Suffrage (De sancto Ieronimo) would indicate that the present placement was intended, suggesting that Jerome had some special significance for the patron. Pictures of Jerome in Penance became increasingly popular at this time: a similar image by the Master of Claude de France, for example, was inserted in the 1510s to Poyer's Hours of Mary of England, probably by King Louis XII when he had the book remodeled for his last wife.