Thoreau’s Journal: A Life of Listening

Read and listen to Thoreau’s personal reflections on nature, friendship, slavery, and society.

For a quarter century, American author Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) filled notebook after notebook with his observations and reflections, strong in the belief that a closely examined life would yield infinite riches. “By some fortunate coincidence of thought or circumstance,” he wrote in 1852, “I am attuned to the universe – I am fitted to hear – my being moves in a sphere of melody.” The selections presented here provide just a glimpse into his voluminous journal. They exemplify his lifelong practice of paying close attention to the world with his heart, mind, and senses—and keeping track of it all, day by day and year by year.

Learn more

For more about Thoreau and his journal, visit the website of The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau (Princeton University Press), which is publishing the complete, accurate text of the journal for the first time. Images and transcripts of every page of Thoreau’s last sixteen journal notebooks, which have not yet appeared in the print edition, are available here. The Morgan is grateful to Dr. Elizabeth Hall Witherell, Editor-in-Chief, and the edition’s entire editorial team.

About the readers

These excerpts from Thoreau’s journal are read aloud by students in New York University’s 2015 and 2016 first-year seminar on Emerson and Thoreau, taught by Professor Philip Kunhardt, Distinguished Scholar in Residence in the Humanities and founding director of the University’s Center for the Study of Transformative Lives.

Cameron Fachman

Sabrina de Silva

Eren Uman

Kaylen Hayes

Trevor James Barker

Carson Kessler

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal, on view from June 2 to September 10, 2017, at the Morgan and from September 29, 2017, to January 21, 2018, at the Concord Museum. The exhibition was organized by the Morgan Library & Museum and the Concord Museum, Concord, Massachusetts.

This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal is made possible with lead funding from an anonymous donor, generous support from the Gilder Foundation, and assistance from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation.

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862). Journal for 12 January–28 March 1852. MA 1302.15. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

The Protester: April 1851

Audio: Read by Cameron Fachman

On April 19, 1851, Thoreau’s neighbors gathered in Concord to celebrate, as they did every year, the symbolic start to the American Revolution. They came together at the spot where, in 1775, an assemblage of local militia had repelled a British advance after Paul Revere and others had sounded the alarm. But Thoreau was in no mood to celebrate. Massachusetts had just sent a man named Thomas Sims back to Georgia in compliance with the Fugitive Slave Act, which affirmed the rights of slaveholders by requiring the detention and return of “fugitives from labor.” Sims was publicly whipped, sent to jail, and put back on the auction block. How, Thoreau demanded, could we celebrate freedom and justice in the face of such a “moral earthquake”? Many of the words he wrote in his journal that April would make their way into his lecture “Slavery in Massachusetts,” a fierce indictment of American hypocrisy.

On April 19, 1851, Thoreau’s neighbors gathered in Concord to celebrate, as they did every year, the symbolic start to the American Revolution. They came together at the spot where, in 1775, an assemblage of local militia had repelled a British advance after Paul Revere and others had sounded the alarm. But Thoreau was in no mood to celebrate. Massachusetts had just sent a man named Thomas Sims back to Georgia in compliance with the Fugitive Slave Act, which affirmed the rights of slaveholders by requiring the detention and return of “fugitives from labor.” Sims was publicly whipped, sent to jail, and put back on the auction block. How, Thoreau demanded, could we celebrate freedom and justice in the face of such a “moral earthquake”? Many of the words he wrote in his journal that April would make their way into his lecture “Slavery in Massachusetts,” a fierce indictment of American hypocrisy.

In [17]75 two or three hundreds of the inhabitants of Concord assembled at one of the bridges with arms in their hands to assert the right of three millions to tax themselves, & have a voice in governing themselves– About a week ago the authorities of Boston, having the sympathy of many of the inhabitants of Concord, assembled in the grey of the dawn, assisted by a still larger armed force – to send back a perfectly innocent man – and one whom they knew to be innocent – into a slavery as complete as the world ever knew. . . . I wish you to consider this – who the man was – whether he was Jesus Christ or another – for in as much as ye did it unto the least of these his brethren ye did it unto him. Do you think he would have stayed here in liberty and let the black man go into slavery in his stead? They sent him back, I say, to live in slavery with [an]other three millions – mark that – whom the same slave power or slavish power, north & south, holds in that condition. Three millions who do not, like the first mentioned, assert the right to govern themselves but simply to run away & stay away from their prison-house.

Just a week afterward those inhabitants of this town who especially sympathize with the authorities of Boston in this their deed caused the bells to be rung & the cannons to be fired to celebrate the courage & the love of liberty of those men who assembled at the bridge. As if those three millions had fought for the right to be free themselves – but to hold in slavery three million others. . . .

Every humane & intelligent inhabitant of Concord when he or she heard those bells & those cannon thought not so much of the events of the 19th of April 1775 as of the events of the 12 of April 1851.

I wish my townsmen to consider that whatever the human law may be, neither an individual nor a nation can ever deliberately commit the least act of injustice without having to pay the penalty for it. A government which deliberately enacts injustice – & persists in it! – it will become the laughing stock of the world.

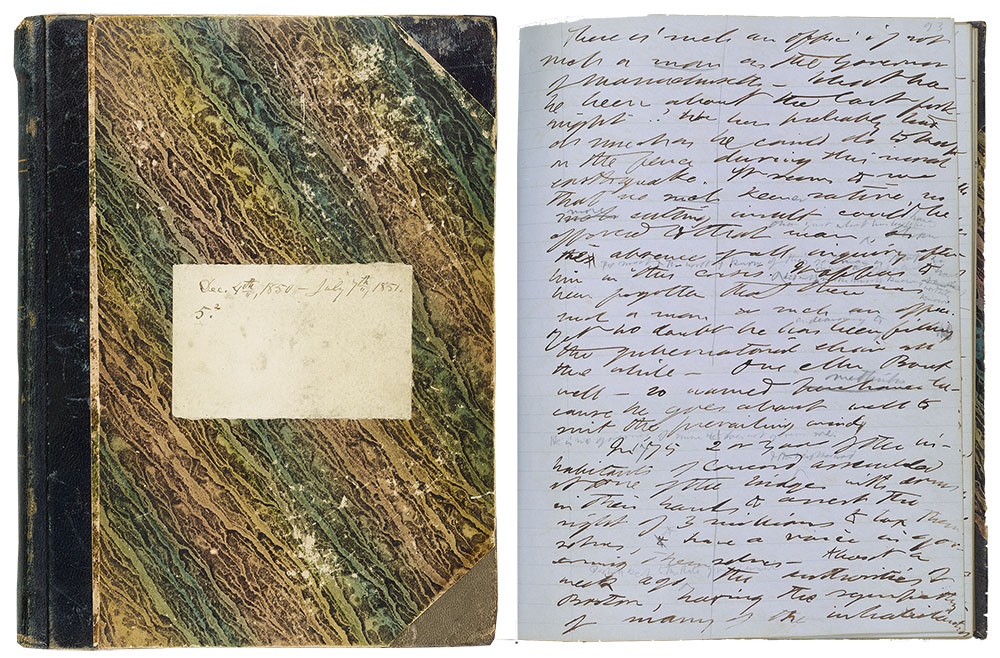

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 4 December 1850–7 July 1851. MA 1302.11. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909. (The quoted passage begins about three-quarters of the way down the manuscript page.)

The Listener: 17 August 1851

Audio: Read by Carson Kessler

Not only was Thoreau deeply responsive to music; he was awake to the natural sounds of birds, frogs, crickets, winds, and rushing water. In a sense, his entire practice of living and journal keeping was built around the concept of listening—remaining attuned to the universe and on the alert for its lessons. He wrote this extraordinary journal entry in 1851, when he was thirty-five, after a period of internal struggle. By listening, he found a way forward.

Not only was Thoreau deeply responsive to music; he was awake to the natural sounds of birds, frogs, crickets, winds, and rushing water. In a sense, his entire practice of living and journal keeping was built around the concept of listening—remaining attuned to the universe and on the alert for its lessons. He wrote this extraordinary journal entry in 1851, when he was thirty-five, after a period of internal struggle. By listening, he found a way forward.

For a day or two it has been quite cool – a coolness that was felt even when sitting by an open window in a thin coat on the west side of the house in the morning – & you naturally sought the sun at that hour– The coolness concentrated your thought however– As I could not command a sunny window I went abroad on the morning of the 15th and lay in the sun in the fields in my thin coat though it was rather cool even there. I feel as if this coolness would do me good. If only it makes my life more pensive why should pensiveness be akin to sadness. There is a certain fertile sadness which I would not avoid but rather earnestly seek– It is positively joyful to me– It saves my life from being trivial. My life flows with a deeper current – no longer as a shallow & brawling stream parched & shrunken by the summer heats– This coolness comes to condense the dews & clear the atmosphere. The stillness seems more deep & significant – each sound seems to come from out a greater thoughtfulness in nature – as if nature had acquired some character & mind – the cricket – the gurgling – stream – the rushing wind amid the trees – all speak to me soberly yet encouragingly of the steady onward progress of the universe– My heart leaps into my mouth at the sound of the wind in the woods– I whose life was but yesterday so desultory & shallow – suddenly recover my spirits – my spirituality through my hearing– I see a goldfinch go twittering through the still louring day and am reminded of the peeping flocks which will soon herald the thoughtful season– Ah! if I could so live that there should be no desultory moment in all my life! That in the trivial season when small fruits are ripe my fruits might be ripe also that I could watch nature always with my moods! That in each season when some part of nature especially flourishes – then a corresponding part of me may not fail to flourish Ah, I would walk I would sit & sleep with natural piety– What if I could pray aloud or to myself as I went along by the brooksides a cheerful prayer like the birds! For joy I could embrace the earth– I shall delight to be buried in it. And then to think of those I love among men – who will know that I love them though I tell them not. I sometimes feel as if I were rewarded merely for expecting better hours– I did not despair of worthier moods – and now I have occasion to be grateful for the flood of life that is flowing over me. I am not so poor– I can smell the ripening apples – the very rills are deep – the autumnal flowers the trichostema dichotoma – not only its bright blue flower above the sand but its strong wormwood scent which belongs to the season feed my spirit – endear the earth to me – make me value myself & rejoice– The quivering of pigeons’ wings – reminds me of the tough fibre of the air which they rend. I thank you God. I do not deserve anything I am unworthy of the least regard & yet I am made to rejoice. I am impure & worthless – & yet the world is gilded for my delight & holidays are prepared for me – & my path is strewn with flowers.

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 8 July–20 August 1851. MA 1302.12. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

The Skeptic: 3 February 1852

Audio: Read by Sabrina de Silva

Thoreau graduated from Harvard in 1837 and returned to campus throughout his life to make use of the university’s fine library and to chat with Thaddeus William Harris, the librarian and entomologist with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship. The occasional trek from his home in Concord, Massachusetts, into Boston and Cambridge (sixteen miles away) took an emotional toll on him, as this entry reveals. At the time he wrote it, he was thirty-four and busy—working as a land surveyor, revising his second book, Walden, collecting botanical data, assisting escaped slaves who were passing through Concord, and keeping track of it all in his journal.

Thoreau graduated from Harvard in 1837 and returned to campus throughout his life to make use of the university’s fine library and to chat with Thaddeus William Harris, the librarian and entomologist with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship. The occasional trek from his home in Concord, Massachusetts, into Boston and Cambridge (sixteen miles away) took an emotional toll on him, as this entry reveals. At the time he wrote it, he was thirty-four and busy—working as a land surveyor, revising his second book, Walden, collecting botanical data, assisting escaped slaves who were passing through Concord, and keeping track of it all in his journal.

I have been to the Libraries (yesterday) at Cambridge & Boston. It would seem as if all things compelled us to originality. How happens it that I find not in the country, in the field & wood the works even of like minded naturalists & poets– Those who have expressed the purest & deepest love of nature – have not recorded it on the bark of the trees with the lichens – they have left no memento of it there – but if I would read their books I must go to the city – so strange & repulsive both to them & to me – & deal with men & institutions with whom I have no sympathy. When I have just been there on this errand, it seems too great a price to pay, for access even to the works of Homer or Chaucer – or Linnaeus. Greece & Asia Minor should henceforth bear Iliads & Odysseys as their trees lichens. But no! If the works of nature are in any sense collected in the forest – the works of man are to a still greater extent collected in the city. I have sometimes imagined a library i.e. a collection of the works of true poets philosophers naturalists &c deposited not in a brick or marble edifice in a crowded & dusty city – guarded by cold-blooded & methodical officials – & preyed on by bookworms – In which you own no share, and are not likely to – but rather far away in the depths of a primitive forest – like the ruins of central America – where you can trace a series of crumbling alcoves – the older books protecting the more modern from the elements – partially buried by the luxuriance of nature – which the heroic student could reach only after adventures in the wilderness, amid wild beasts & wild men– That to my imagination seems a fitter place for these interesting relics, which owe no small part of their interest to their antiquity – and whose occasion is nature – than the well preserved edifice – with its well preserved officials on the side of a city’s square–

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 12 January–28 March 1852. MA 1302.15. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909. (The quoted passage begins about half-way down the manuscript page.)

The Friend: 4 April 1852

Audio: Read by Eren Uman

Thoreau wrote little in his journal about personal relationships, but he did describe the pain of navigating one very important one. The man Thoreau referred to simply as “my friend” was Ralph Waldo Emerson, the dynamic mentor who had first encouraged him to keep a journal. Emerson saw great promise in young Thoreau—he included him in Transcendentalist discussion groups, promoted his early writings, and touted him as the next great American voice. Thoreau even lived with Emerson for awhile, developing strong bonds with the entire household. But frustrations grew on both sides. In this agonized entry, Thoreau took to heart Emerson’s accusations—echoed by some but refuted by many—that he was a “cold intellectual skeptic” who shared more with his journal than he did with his friends.

Thoreau wrote little in his journal about personal relationships, but he did describe the pain of navigating one very important one. The man Thoreau referred to simply as “my friend” was Ralph Waldo Emerson, the dynamic mentor who had first encouraged him to keep a journal. Emerson saw great promise in young Thoreau—he included him in Transcendentalist discussion groups, promoted his early writings, and touted him as the next great American voice. Thoreau even lived with Emerson for awhile, developing strong bonds with the entire household. But frustrations grew on both sides. In this agonized entry, Thoreau took to heart Emerson’s accusations—echoed by some but refuted by many—that he was a “cold intellectual skeptic” who shared more with his journal than he did with his friends.

I have got to that pass with my friend – that our words do not pass with each other for what they are worth. We speak in vain – there is none to hear. He finds fault with me that I walk alone, when I pine for want of a companion – that I commit my thoughts to a diary even on my walks instead of seeking to share them generously with a friend – curses my practice even– Awful as it is to contemplate I pray that if I am the cold intellectual skeptic whom he rebukes his curse may take effect – & wither & dry up those sources of my life – and my journal no longer yield me pleasure nor life.

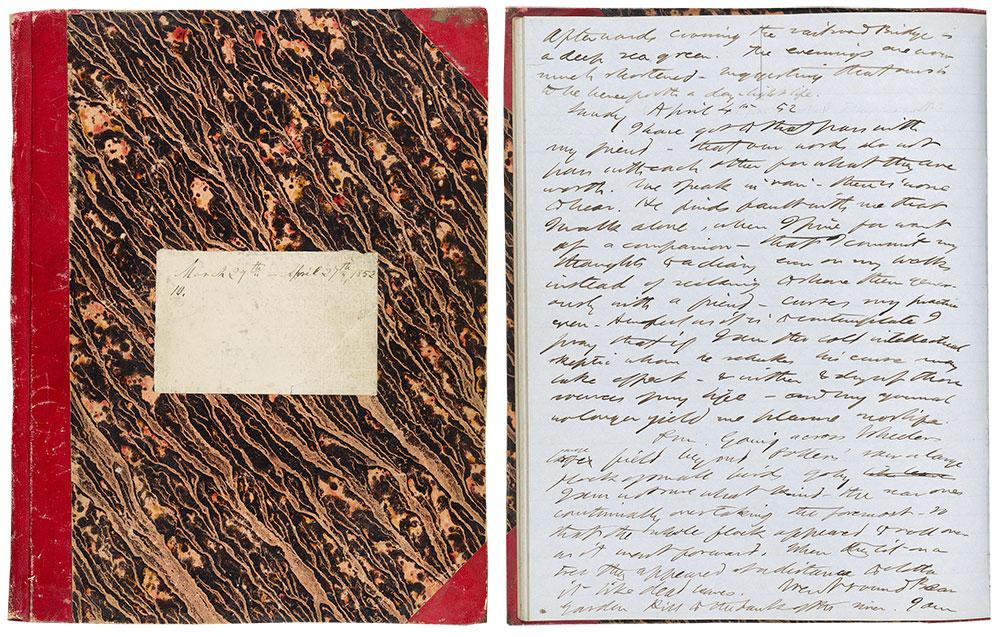

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 29 March–27 April 1852. MA 1302.16. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

The Transcendentalist: 5 March 1853

Audio: Read by Kaylen Hayes

In response to an 1853 inquiry from Spencer Fullerton Baird, the first curator of the Smithsonian Institution and secretary of a major scientific body, Thoreau filled out a questionnaire, listing his occupations as “Literary and Scientific, Combined with Land-surveying.” He highlighted his interest in the indigenous peoples of the Algonkian language group and cited the great Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt as a particular inspiration. But in this journal entry, Thoreau revealed what was really on his mind as he completed Baird’s survey. How he could convey to scientists (without inviting ridicule) that he was “a mystic – a transcendentalist – & a natural philosopher to boot”?

In response to an 1853 inquiry from Spencer Fullerton Baird, the first curator of the Smithsonian Institution and secretary of a major scientific body, Thoreau filled out a questionnaire, listing his occupations as “Literary and Scientific, Combined with Land-surveying.” He highlighted his interest in the indigenous peoples of the Algonkian language group and cited the great Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt as a particular inspiration. But in this journal entry, Thoreau revealed what was really on his mind as he completed Baird’s survey. How he could convey to scientists (without inviting ridicule) that he was “a mystic – a transcendentalist – & a natural philosopher to boot”?

The Secretary for the Association for the Ad. of Science – requested me as he probably has thousands of others – by a printed circular letter from Washington the other day – to fill the blanks against certain questions – among which the most important one was – what branch of science I was specially interested in – Using the term science in the most comprehensive sense possible– Now though I could state to a select few that department of human inquiry which engages me – & should be rejoiced at an opportunity so to do – I felt that it would be to make my-self the laughing stock of the scientific community – to describe or attempt to describe to them that branch of science which specially interests me – in as much as they do not believe in a science which deals with the higher law. So I was obliged to speak to their condition and describe to them that poor part of me which alone they can understand. The fact is I am a mystic – a transcendentalist – & a natural philosopher to boot. Now I think of it – I should have told them at once that I was a transcendentalist – that would have been the shortest way of telling them that they would not understand my explanations.

How absurd that though I probably stand as near to nature as any of them, and am by constitution as good an observer as most – yet a true account of my relation to nature should excite their ridicule only. If it had been the secretary of an association of which Plato or Aristotle was the President – I should not have hesitated to describe my studies at once & particularly.

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 8 January–8 March 1853. MA 1302.20. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909. (The quoted passage begins about a third of the way down the manuscript page.)

The Saunterer: 5 December 1856

Audio: Read by Eren Uman

One of the most frequently quoted lines from Thoreau’s journal is this paean to his native Concord: I have never got over my surprise that I should have been born into the most estimable place in all the world – & in the very nick of time, too. But what was he doing on the day that joy spilled forth? As usual, he was walking. It was early December, and he passed some children playing in the snow. He saw a half moon in the afternoon sky and listened to a pair of nuthatches sing tut tut as they swooped by a walnut tree. Then, back home at his desk, he wrote about his day. After sketching a few sprigs of Saint-John’s-wort or pinweed he had seen poking out of the crusted snow, he wrote these ecstatic words.

One of the most frequently quoted lines from Thoreau’s journal is this paean to his native Concord: I have never got over my surprise that I should have been born into the most estimable place in all the world – & in the very nick of time, too. But what was he doing on the day that joy spilled forth? As usual, he was walking. It was early December, and he passed some children playing in the snow. He saw a half moon in the afternoon sky and listened to a pair of nuthatches sing tut tut as they swooped by a walnut tree. Then, back home at his desk, he wrote about his day. After sketching a few sprigs of Saint-John’s-wort or pinweed he had seen poking out of the crusted snow, he wrote these ecstatic words.

My themes shall not be far fetched– I will tell of homely everyday phenomena & adventures– Friends–! society–! It seems to me that I have an abundance of it– there is so much that I rejoice & sympathize with – & men too that I never speak to but only know & think of. What you call bareness & poverty – is to me simplicity: God could not be unkind to me if he should try. I love the winter with its imprisonment & its cold – for it compels the prisoner to try new fields & resources– I love to have the river closed up for a season & a pause put to my boating, to be obliged to get my boat in– I shall launch it again in the spring with so much more pleasure– This is an advantage in point of abstinence and moderation compared with the sea-side boating – where the boat ever lies on the shore.– I love best to have each thing in its season only – & enjoy doing without it at all other times. It is the greatest of all advantages to enjoy no advantage at all. I find it invariably true the poorer I am the richer I am.

What you consider my disadvantage, I consider my advantage– While you are pleased to get knowledge & culture in many ways I am delighted to think that I am getting rid of them. I have never got over my surprise that I should have been born into the most estimable place in all the world – & in the very nick of time too.

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 7 September 1856–1 April 1857. MA 1302.28. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909. (The photograph depicts the manuscript page preceding the quoted passage.)

The Surveyor: 29 October 1857

Audio: Read by Trevor James Barker

Land surveying was Thoreau’s chief source of income when he was in his thirties and forties, and he was good at it. On one hand, the work allowed him to spend time outdoors, exercise, and listen to birdsong. On the other hand, he tended to eat poorly and neglect his personal pursuits while he was out on the job. Shortly after he turned forty, he wrote this journal entry. He had just awoken from a recurring dream of ascending a mountain, which led him to think about the true business of life. He concluded that, on balance, he had chosen the professions best suited to his temperament. “I have aspired to practice in succession all the honest arts of life,” he wrote, “that I may gather all their fruits.”

Land surveying was Thoreau’s chief source of income when he was in his thirties and forties, and he was good at it. On one hand, the work allowed him to spend time outdoors, exercise, and listen to birdsong. On the other hand, he tended to eat poorly and neglect his personal pursuits while he was out on the job. Shortly after he turned forty, he wrote this journal entry. He had just awoken from a recurring dream of ascending a mountain, which led him to think about the true business of life. He concluded that, on balance, he had chosen the professions best suited to his temperament. “I have aspired to practice in succession all the honest arts of life,” he wrote, “that I may gather all their fruits.”

I know of no such amusement – so wholesome & in every sense profitable – for instance as to spend an hour or two in a day – picking some berries or other fruits which will be food for the winter – or collecting drift wood from the river for fuel – or cultivating the few beans or potatoes which I want – Theaters & operas – which intoxicate for a season – are nothing compared to these pursuits. And so it is with all the true arts of life – Farming & building – & manufacturing & sailing are the greatest & wholesomest amusements that were ever invented (for God invented them) & I suppose that the farmers & mechanics know it – only I think they indulge to excess generally, & so what was meant for a joy becomes the sweat of their brow. . . . It is a great amusement & more profitable than I could have invented – to go & spend an afternoon now picking cranberries– By these various pursuits your experience becomes singularly complete & founded. The novelty & significance of such pursuits are remarkable. – Such is the path by which we climb to the heights of our being – & compare the poetry which such simple pursuits have inspired – with the unreadable volumes which have been written about art.

Who is the most profitable companion – he who has been picking cranberries & chopping wood – or he who has been attending the opera all his days? I find when I have been building a fence or surveying a farm – or even collecting simples – that these were the true paths to perception & enjoyment. My being seems to have put forth new roots – to be more strongly planted. This is the true way to crack the nut of happiness. If as a poet or naturalist – you wish to explore a given neighborhood – go and live in it – i.e get your living in it – fish in its streams – hunt in its forests – gather from its waters or its woods – cultivate the ground – & pluck the wild fruits – &c &c this will be the surest & speediest way to those perceptions you covet.

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 31 July–25 November 1857. MA 1302.30. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

The Naturalist: 11 November 1858

Audio: Read by Sabrina de Silva

In November 1858, one of Thoreau’s neighbors shot a hawk that had been after his chickens. Thoreau took the bird home and examined it, checking his copy of Wilson’s American Ornithology to identify the species precisely. He felt a kinship with this particular bird. “The same thing which keeps the hen hawk in the woods – away from the cities – keeps me here,” he wrote. The day he made this entry, he had gone rowing, as he often did, and taken note of all the signs of approaching winter, reveling just as much in the frost and decay as he did in the brighter signs of spring and summer. Back home, he examined the young hen hawk’s feather—an ordinary thing, rarely seen or appreciated by humans—and found such beauty in it that he made a drawing of it in his journal. Of more than eight hundred little sketches Thoreau made in his journal over the course of several decades, this is one of the most dramatic.

In November 1858, one of Thoreau’s neighbors shot a hawk that had been after his chickens. Thoreau took the bird home and examined it, checking his copy of Wilson’s American Ornithology to identify the species precisely. He felt a kinship with this particular bird. “The same thing which keeps the hen hawk in the woods – away from the cities – keeps me here,” he wrote. The day he made this entry, he had gone rowing, as he often did, and taken note of all the signs of approaching winter, reveling just as much in the frost and decay as he did in the brighter signs of spring and summer. Back home, he examined the young hen hawk’s feather—an ordinary thing, rarely seen or appreciated by humans—and found such beauty in it that he made a drawing of it in his journal. Of more than eight hundred little sketches Thoreau made in his journal over the course of several decades, this is one of the most dramatic.

Snow fleas are skipping on the surface of the water at the edge & spiders running about. These become prominent now–

The waters look cold & empty of fish & most other inhabitants now. Here in the sun in the shelter of the wood – the smooth shallow water, with the stubble standing in it – is waiting for ice – indeed ice that formed last night must have recently melted in it. The sight of such water now reminds me of ice as much as of water. No doubt many fishes have gone into winter quarters. . . .

Gossamer reflecting the light – is another November phenomenon (as well as October). I see here looking toward the sun a very distinct silvery sheen from the cranberry vines – (as from a thousand other November surfaces) though looking down on them they are dark purple. . . . Coming home I have cold fingers & must row to get warm.

In the meadows the pitcher plants are bright red. This is the month of nuts and nutty thoughts – this November whose name sounds so bleak and cheerless – perhaps its harvest of thought is worth more than all the other crops of the year– Men are more serious now. . .

The tail coverts of the young hen hawk, i.e. this year’s bird at present – are white very handsomely barred or watered with dark brown in an irregular manner somewhat as above – the bars on opposite sides of the midrib – alternating in an agreeable manner– Such natural objects have suggested the “watered” figures or colors in the arts– Few mortals ever look down on the tail coverts of a young hen hawk – yet these are not only beautiful, but of a peculiar beauty – being differently marked & colored (to judge from Wilson’s ac. of the old) from those of the old bird. Thus she finishes her works above men’s sight.

Henry David Thoreau’s journal for 9 November 1858–7 April 1859. MA 1302. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.