Word and Image: Martin Luther's Reformation

Few figures in history are as influential or divisive as Martin Luther. How did one monk at the edge of the German Empire divide the Church and completely alter the course of Western history?

The printing and distribution of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses against the sale of indulgences initiated a movement that would not have been possible before the invention of movable type. The Reformation engaged authors, artists, politicians, priests, and printers throughout Europe in a battle over religious doctrine—a subject previously relegated to a select few. Luther and his colleagues expertly employed the still relatively new technology of the printing press to communicate to the masses, and master artists elaborated their texts with woodcut imagery. Artists also created independent works of art to depict and spread the reformer’s message. Authors and artists on both sides of the Reformation produced an avalanche of material for mass consumption. The Reformation was a fight over religious belief that was won by means of successful communication through word and image.

This presentation provides an overview of the exhibition Word and Image: Martin Luther's Reformation, on view October 7, 2016 through January 22, 2017, highlighting a few pieces and the overall themes.

Word and Image: Martin Luther's Reformation is made possible with the support of the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany and under the patronage of Federal Foreign Minister Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier within the framework of the Luther Decade in cooperation with the Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt, the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, and the Foundation Schloss Friedenstein Gotha, under the leadership of the State Museum of Prehistory, Halle, and in coordination with the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

It is also made possible with generous support from the Johansson Family Foundation and Kurt F. Viermetz, Munich, and assistance from the Arnhold Foundation.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther, 1529. Oil on panel. 41.9 x 28.5 cm. Gotha, Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein.

Young Martin

On the left we have one of Lucas Cranach’s first portrayals of Luther: a youthful Luther before notoriety and infamy. In traditional Christian practice, private devotion was focused towards the saints, the intercessors who helped in daily life and who provided a pathway to the divine. When Luther was nearly struck by lightning, it was St. Anne, shown here in an early sixteenth-century sculpture, to whom he turned and made the fateful pledge that, if she would save him, he would abandon the study of law for a life in the monastery.

On the left we have one of Lucas Cranach’s first portrayals of Luther: a youthful Luther before notoriety and infamy. In traditional Christian practice, private devotion was focused towards the saints, the intercessors who helped in daily life and who provided a pathway to the divine. When Luther was nearly struck by lightning, it was St. Anne, shown here in an early sixteenth-century sculpture, to whom he turned and made the fateful pledge that, if she would save him, he would abandon the study of law for a life in the monastery.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther as a Monk, 1520. Oil on panel. Free State of Saxony-Anhalt (on permanent loan to the Luther House, Wittenberg).

Saint Anne with Mary as a Child, ca. 1520. Polychrome limewood. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Works of Art in Medieval and Early- Modern Devotion

In medieval and early-modern devotion, works of art helped focus the devotee’s attention and channel prayers toward the divine. This pair of paintings by Lucas Cranach shows Saints Anthony and Sebastian, two saints who were thought to help cure plague and disease. One type of object that artists fashioned was reliquaries, elaborate precious-metal pieces made to enshrine holy objects. The cross reliquary shown is from the collection of Friedrich the Wise, Elector of Saxony, whose Castle Church in Wittenberg housed one of the largest collections of relics in Europe.

In medieval and early-modern devotion, works of art helped focus the devotee’s attention and channel prayers toward the divine. This pair of paintings by Lucas Cranach shows Saints Anthony and Sebastian, two saints who were thought to help cure plague and disease. One type of object that artists fashioned was reliquaries, elaborate precious-metal pieces made to enshrine holy objects. The cross reliquary shown is from the collection of Friedrich the Wise, Elector of Saxony, whose Castle Church in Wittenberg housed one of the largest collections of relics in Europe.

Devotional deeds—such as visiting holy sites or communing with certain saints via a reliquary—could earn an individual benefits, what are known as indulgences, the remission from the temporal punishment for sins. The abuse of the common practice of selling indulgences was what instigated Luther’s schism with the Church.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Saint Anthony and Saint Sebastian, ca. 1520. Oil on panel. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Drawing of a Cross Reliquary, 1509. Pen and ink on paper. Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Weimar.

Indulgences and the Ninety-Five Theses

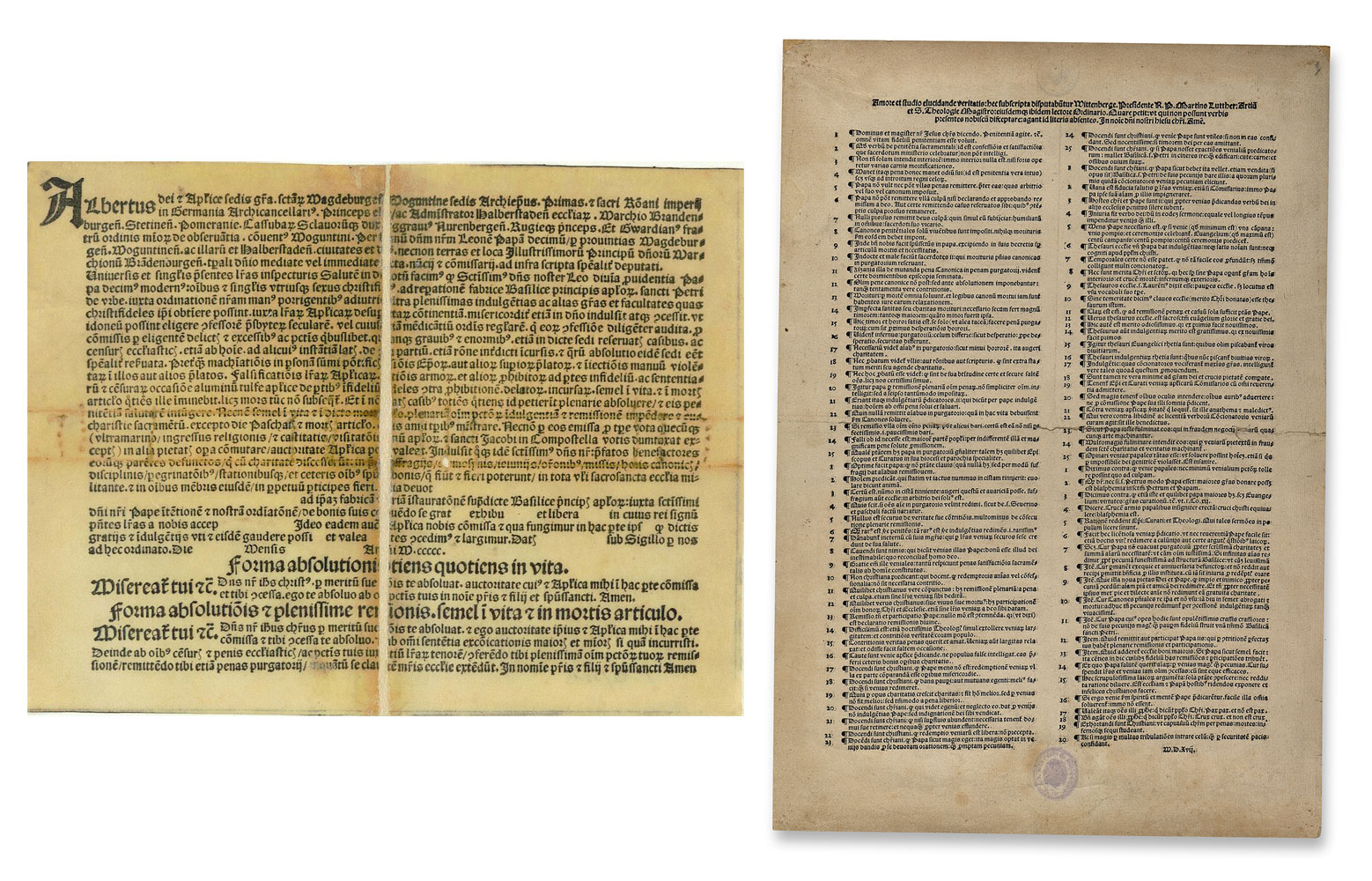

In 1515 a new papal indulgence, shown on the left, was issued in exchange for donations to fund the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. This small printed form would have been filled out with the name of the recipient and date of purchase. However, this copy remained blank because it was never purchased. Ultimately it was cut in half and recycled as a book cover.

In 1515 a new papal indulgence, shown on the left, was issued in exchange for donations to fund the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. This small printed form would have been filled out with the name of the recipient and date of purchase. However, this copy remained blank because it was never purchased. Ultimately it was cut in half and recycled as a book cover.

Luther, by 1515 a professor of theology in Wittenberg, saw no scriptural or theological foundation for the sale of indulgences and vehemently objected to the fleecing of the faithful by unscrupulous indulgence sellers who tried to sell salvation. Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses―on the right in one of only six existing printed broadside, or single-page, copies―is a list of points for a university debate on the moral and ethical validity of indulgences. Just like the announcement for any other university debate, a copy like this would have been posted to the doors of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. The debate never happened, but we are now celebrating the 500th anniversary of the storm that followed Luther’s Theses, his challenge to Church tradition.

Albrecht of Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, Papal Indulgence for the Construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Leipzig: Melchior Lotter the Elder, 1515. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, “The Ninety-Five Theses,” Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum (Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences). Nuremberg: Hieronymous Hötzel, 1517. Österreichisches Staatsarchiv/Abteilung Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv.

Media War

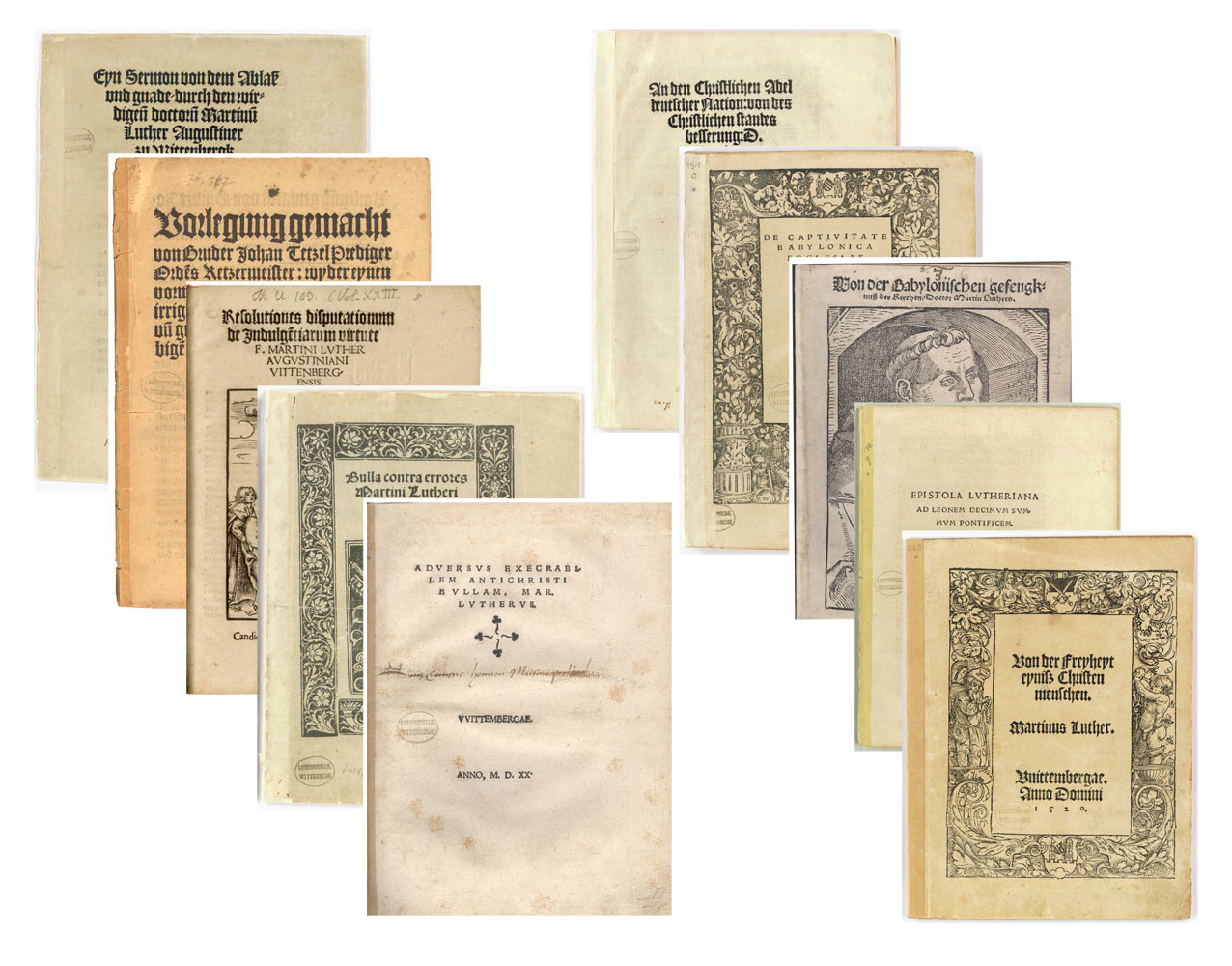

The media war that followed the Theses was waged through the help of the printing press, with Luther and those loyal to Rome unleashing attacks on each other in short pamphlets that were quickly and easily disseminated from presses across Germany. In Luther’s publications, he started laying out his ideas of religious reform, which went against centuries of church tradition. It was these publications that directly lead to Luther being called to stand trial before Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521.

The media war that followed the Theses was waged through the help of the printing press, with Luther and those loyal to Rome unleashing attacks on each other in short pamphlets that were quickly and easily disseminated from presses across Germany. In Luther’s publications, he started laying out his ideas of religious reform, which went against centuries of church tradition. It was these publications that directly lead to Luther being called to stand trial before Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521.

Martin Luther, Ein sermon von Ablass und Gnade (A Sermon on Indulgences and Grace). Leipzig: Wolfgang Stöckel, 1518. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Johann Tetzel, Vorlegung gemacht von Bruder Johan Tetzel Prediger Ordens Ketzermeister (Rebuttal Made by Brother Johann Tetzel, the Order of Preachers’ Inquisitor of Heretics). Leipzig: Melchior Lotter the Elder, 1518. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, Resolutiones disputationum de indulgentarum virtute (Resolutions on the Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences). Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, 1518. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek in Halle (Saale).

Pope Leo X, Exsurge domine. Bulla contra errores Martini Lutheri et sequacium (Bull Against the Errors of Martin Luther and his Followers). Rostock: Ludwig Dietz, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, Adversus execrabilem Antichristi bullam (Against the Detestable Bull of the Antichrist). Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter the Younger, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation (To the Christian Nobles of the German Nation [German]). Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter the Younger, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae praeludium (On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, a Prelude [Latin]). Leipzig: Melchior Lotter the Elder, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Thomas Murner (translator), Von der Babylonischen gefengknusz der Kirchen (On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church [German]). Strasbourg: Johann Schott, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, Epistola Lutheriana ad Leonem decimum. Tractatus de libertate Christiana (Letter from Luther to Leo X. Tract on Christian Liberty [Latin]). Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter the Younger, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, Von der Freyheyt eynisz Christen menschen (On the Freedom of a Christian [German]). Wittenberg: Johann Rhau–Grunenberg, 1520. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Luther on Trial

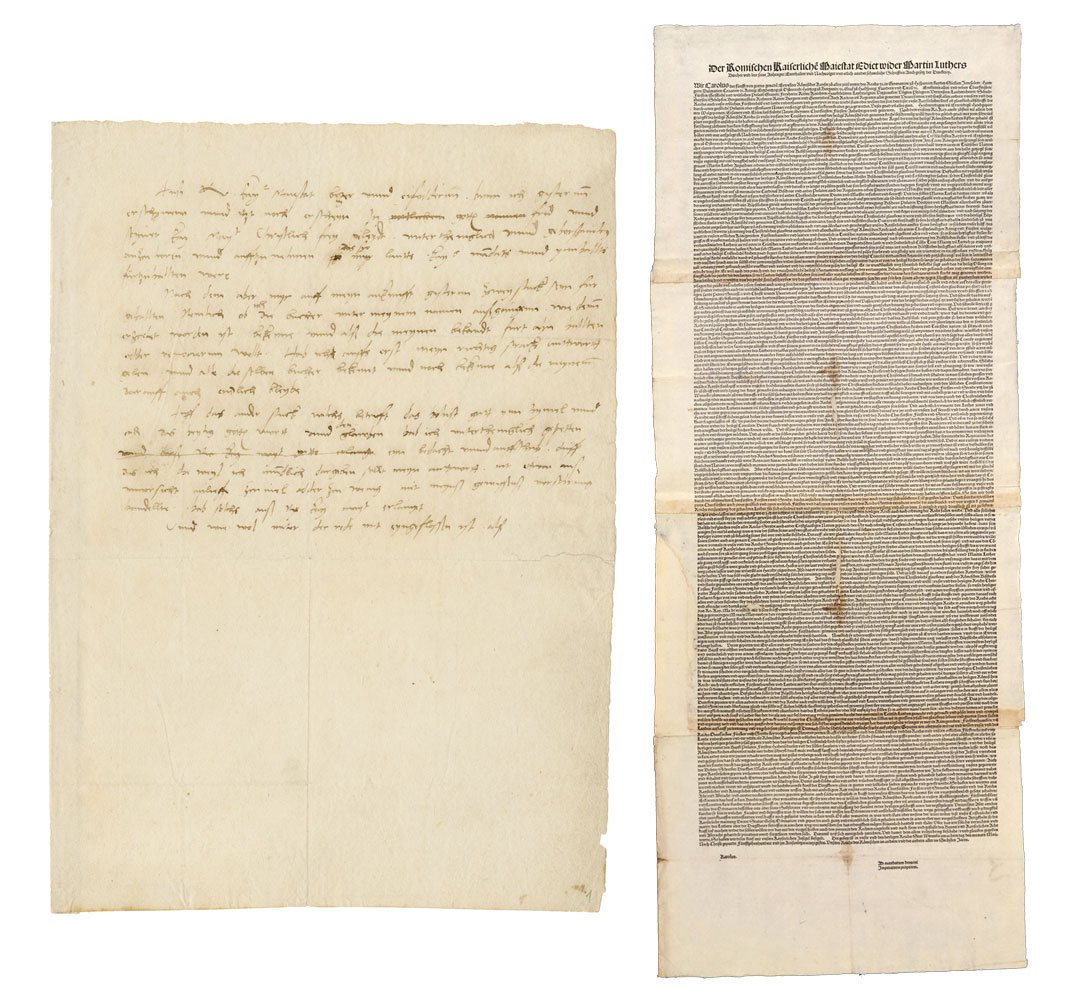

On the left is Luther’s manuscript draft of his opening statement, in which he recites the illustrious titles of those who sit in judgment, but he stops mid-sentence before committing his full defense to paper. Charles V was of course unmoved by Luther’s defense, and the Edict of Worms was issued in May 1521, shown on the right in one of only two known printed copies.

On the left is Luther’s manuscript draft of his opening statement, in which he recites the illustrious titles of those who sit in judgment, but he stops mid-sentence before committing his full defense to paper. Charles V was of course unmoved by Luther’s defense, and the Edict of Worms was issued in May 1521, shown on the right in one of only two known printed copies.

Martin Luther, Manuscript Draft on his Defense Speech at the Diet of Worms. Worms, April 17/18, 1521. Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Ernestinisches Gesamtarchiv, Weimar.

Emperor Charles V, Der Romischen Kaiserlichen Maiestat Edict wider Martin Luthers Bücher und Lere (The Imperial Roman Majesty’s Edict against Martin Luther’s Books and Teaching). Vienna: Johann Singriener, May 8, 1521. German Historical Museum, Berlin.

Letter to Emperor Charles V

Luther fled Worms in April and wrote a letter back to Charles V reiterating his stance and making a second attempt to defend his position. The letter was never given to the emperor (some say because no one was brave enough to deliver it), but it was soon available in print for public consumption. This manuscript letter was purchased at auction in 1911 by Pierpont Morgan, our library’s founder, but within a few months Morgan gave it to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany as a gift to that nation. Since 1911 it has resided in the Luther House in Wittenberg.

Luther fled Worms in April and wrote a letter back to Charles V reiterating his stance and making a second attempt to defend his position. The letter was never given to the emperor (some say because no one was brave enough to deliver it), but it was soon available in print for public consumption. This manuscript letter was purchased at auction in 1911 by Pierpont Morgan, our library’s founder, but within a few months Morgan gave it to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany as a gift to that nation. Since 1911 it has resided in the Luther House in Wittenberg.

Martin Luther, Letter to Emperor Charles V, Friedberg, April 28, 1521. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

The Bible

After Luther wrote his letter to Charles V, supporters secreted him into hiding at Wartburg Castle. Safely away from Charles V, Luther had uninterrupted time to work on his most important work: the translation of the Bible into German. This was not the first time the Bible was translated into German, nor was it the first time the German Bible appeared in print; however, Luther’s translation importantly put scripture into clear German that would have been understandable to a wider group of readers than any earlier version. Luther’s New Testament was published in September of 1522, with a second edition coming out in December of the same year, the so-called September and December Testaments, each adorned with woodcut illustrations by Lucas Cranach. Luther’s translation of the complete Bible was not available in print until 1534, twelve years later.

On the right is Luther’s manuscript draft translation of part of the Old Testament, Second Samuel, Chapters Twenty-two and Twenty-three. Such drafts were usually destroyed in the process of producing the printed book, which makes this survival exhibiting Luther’s working method all the more rare and precious. Luther thought that the printing press was God’s greatest gift for the dissemination of scripture, but the Reformation made use of the press for the complete spectrum of texts and imagery that promulgated and promoted the Reformation and Lutheran theology.

Martin Luther, “The December Testament,” Das Newe Testament Deůtzsch (The New Testament, in German). Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter the Younger, December 1522. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Martin Luther, Draft translation of Old Testament (2 Samuel 22–23). Wittenberg, after 1521. Landesarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Dessau.

Spreading the Word

Printed, illustrated broadsides supported the Lutheran cause and denounced the Roman Church. In the pro-Lutheran image on the left, the Crucifixion scene shows the pope in place of the Bad Thief on Christ’s left; the pope’s cross is on fire and being chopped down by a devil. Reformation publicity was not subtle.

Printed, illustrated broadsides supported the Lutheran cause and denounced the Roman Church. In the pro-Lutheran image on the left, the Crucifixion scene shows the pope in place of the Bad Thief on Christ’s left; the pope’s cross is on fire and being chopped down by a devil. Reformation publicity was not subtle.

Luther and printing presses churned out texts explaining Protestant theology and religious practice and providing scriptural interpretation. During his thirty-year writing career, Luther produced something for the press on average about once every three or four weeks. At the top right is Luther’s instructional guide for the organization of a church service with an decorative title page by Lucas Cranach. Luther, a great lover of religious music, was instrumental in developing congregational singing, a mainstay of many church services today. Remarkably, recent archaeological digs uncovered the tiny printing types, shown at bottom right, used to print the first Lutheran hymnals in Wittenberg from the 1530s to 60s. An extremely rare find, these are the oldest existing pieces of music-printing type in Europe.

Monogrammist IW, Crucifixion with the Pope as the Bad Thief and Antichrist. Magdeburg: Jörg Scheller, about 1545. Foundation Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Martin Luther, Deudsche Messe und ordnung Gottisdienst (German Mass and Order of Holy Service). Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter the Younger, 1526. Luther Memorials Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt.

Georg Rhau’s Music Printing Type. Wittenberg, after 1532. State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, State Museum of Prehistory Halle (Saale).

Luther’s Household Objects

Also uncovered in archaeological digs are objects related to Luther’s household and home life: decorative tiles that adorned the heating stoves that warmed the house (above right), expensive imported pottery and tableware (above left), and personal items, such as the green ceramic inkstand at the bottom, likely used by Luther himself to write the texts to be sent off to the printing presses.

Paul Preuning, Round-bodied Polychrome Pitcher, second-half of the sixteenth century. Polychrome ceramic. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich.

Eve Stove Tile, early-sixteenth century. Polychrome ceramic. Stiftung Moritzburg Halle (Saale), Kunstmuseum des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt.

Ceramic Inkstand, early-sixteenth century. Glazed ceramic. Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, State Museum of Prehistory Halle (Saale).

The Art of Reformation

While the press distributed Luther’s words to the four corners of Europe, his friend and neighbor Lucas Cranach promoted Luther’s image. Above are portraits of Martin Luther and his wife Kathrina von Bora, portrayed by Cranach as the model of the evangelical pastor and pastor’s wife.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora. Wittenberg, 1529. Oil on panel. Foundation Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Adam and Eve

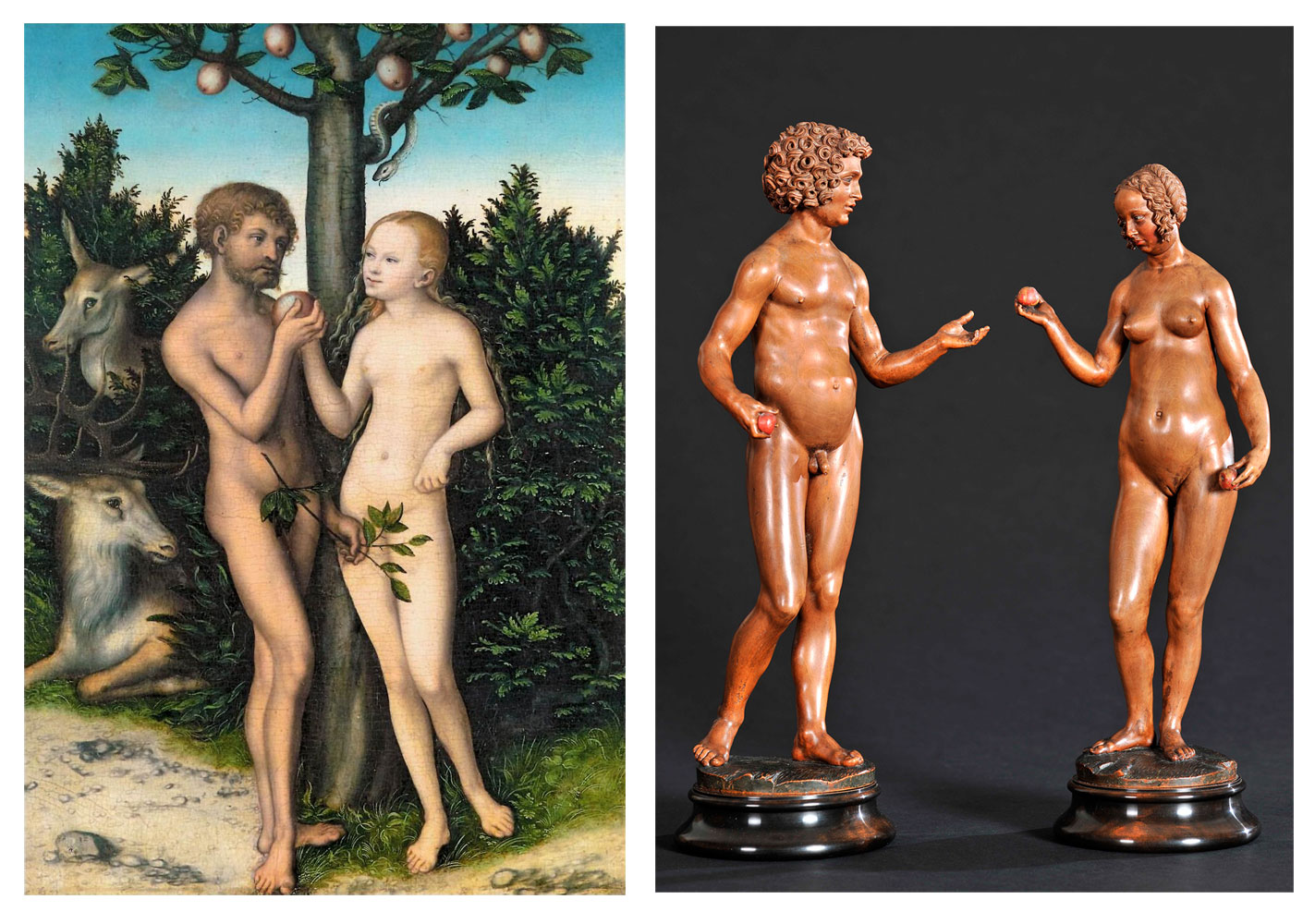

Here you see two exceptional depictions of Adam and Eve: a painting by Lucas Cranach and a sculptural pair by Conrad Meit. These two compositions propose radically different interpretations of the events in the Garden of Eden. For Cranach, Eve seems motivated purely by seduction, but in the Meit, the psychological fear of what is about to happen is palpable in both figures.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Adam and Eve, 1532. Oil on panel. Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg.

Conrad Meit, Adam and Eve, ca. 1510. Limewood. Foundation Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.

Depictions of Christ and Mary

We close with two depictions of Christ and Mary by Lucas Cranach: on your left is a traditional Virgin and Child composition from 1514, and on your right, a jarringly unfamiliar yet somehow comforting depiction from about 1516 to 1520. Nearly contemporary, these two depictions provide differing avenues to the divine. The earlier depiction is full of Italian influences and promotes the traditional dogma that the path to Christ is through the Virgin and the saints. Cranach’s later depiction of an adult Christ and Mary removes every detail of narrative—even making the identification of Mary somewhat questionable. Here Cranach has put us face to face with divine humanity. As with his Bible translation, Luther advocated that art also should be understandable and accessible to a general audience. Perhaps in this exceptional painting we find the greatest depiction of that access to the divine as the very human face of Christ looks out at us: Luther’s priesthood of all believers

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Virgin and Child with St. John as a Boy, about 1514. Oil and tempera on panel. Federal Republic of Germany (on permanent loan to Veste Coburg Kunstsammlungen).

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Christ and Mary, ca. 1516–1520. Oil on parchment on panel. Foundation Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha.