Charlotte Brontë: Ten Letters and a Fictional Fantasy

“I would still endeavour to keep my expectations low respecting the ultimate success of Jane Eyre,” wrote Charlotte Brontë to William S. Williams of the publishing firm Smith, Elder & Co. in October 1847. “A mere domestic novel will I fear seem trivial to men of large views and solid attainments.” How wrong she was! Brontë’s personal letters, a selection of which is presented here, reveal the doubt, pain, hope, and confidence she voiced before emerging as one of the world’s most successful novelists. She confides in friends as she endures a stint as a governess, reveals her true identity to her publisher, and watches her three adult siblings fall mortally ill in quick succession. In 1854, her new husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls, expressed concern about the disposition of the personal letters of his famous wife. “Men’s letters are proverbially uninteresting and uncommunicative,” Brontë told her friend Ellen Nussey. “As to my own notes, I never thought of attaching importance to them, or considering their fate.”

This online exhibition was created in conjunction with the exhibition Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will, on view from September 9, 2016 through January 2, 2017 and organized by Christine Nelson, Drue Heinz Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts.

Charlotte Brontë: An Independent Will is made possible by Fay and Geoffrey Elliott.

The catalogue is underwritten by the Andrew W. Mellon Fund for Research and Publications.

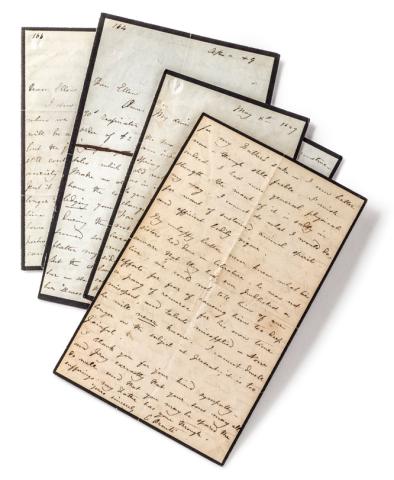

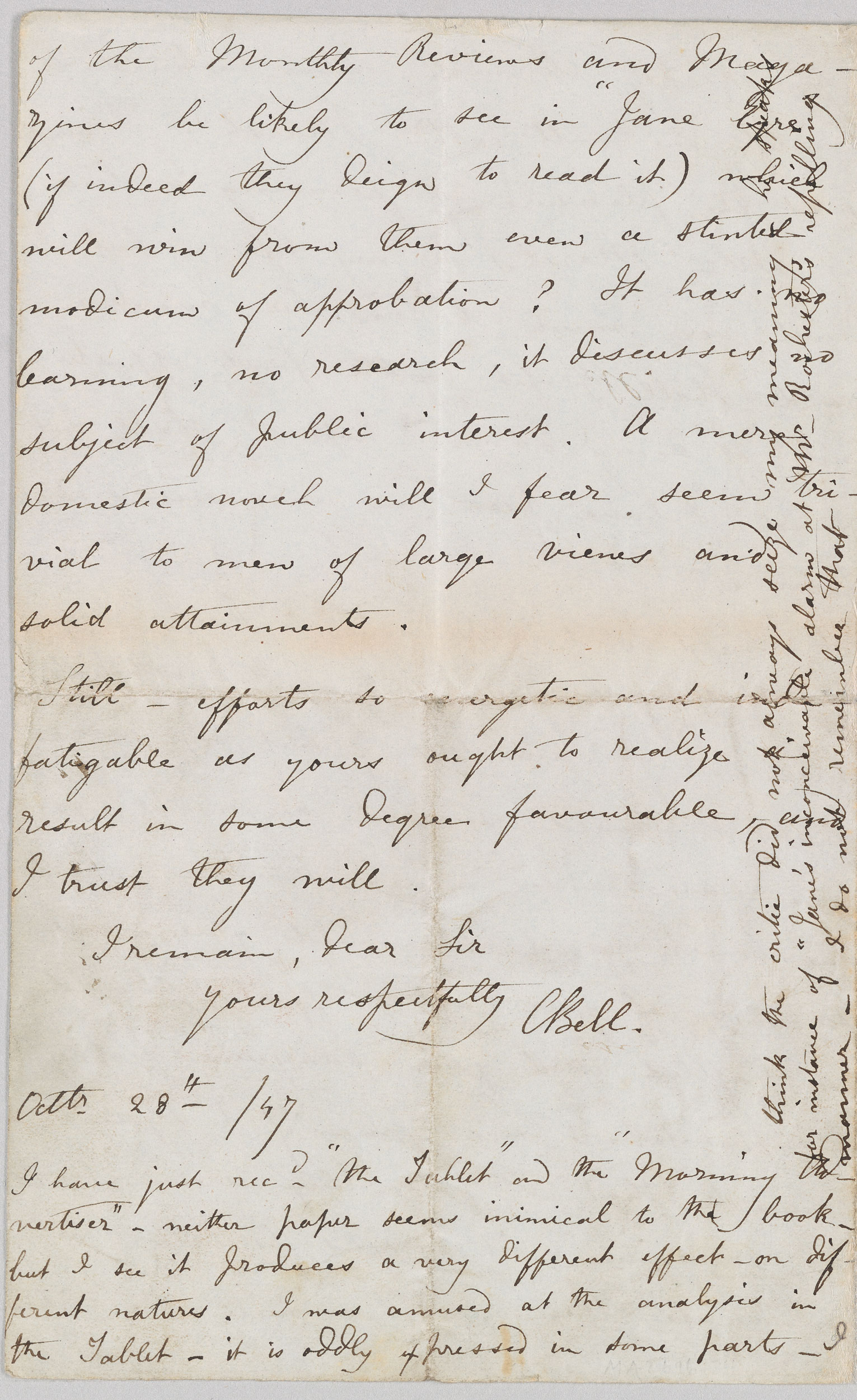

1. Letter to William S. Williams, 28 October 1847, page 1

Letter to William S. Williams of Smith, Elder & Co., dated Haworth, 28 October 1847

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

In this letter to William S. Williams of the firm that had published Jane Eyre, Brontë reacted to some of the early reviews of her first published novel. She defended her portrayal of Helen Burns, a virtuous child who dies in Jane’s arms. Helen was, Brontë implied, a fictional reimagining of her own sister Maria, who had died at the age of eleven after falling ill at the Clergy Daughters’ School.

Dear Sir

Your last letter was very pleasant to me to read, and is very cheering to reflect on. I feel honoured in being approved by Mr Thackeray because I approve Mr Thackeray. This may sound presumptuous perhaps, but I mean that I have long recognized in his writings genuine talent such as I admired, such as I wondered at and delighted in. No author seems to distinguish so exquisitely as he does dross from ore, the real from the counterfeit. I believed too he had deep and true feelings under his seeming sternness – now I am sure he has. One good word from such a man is worth pages of praise from

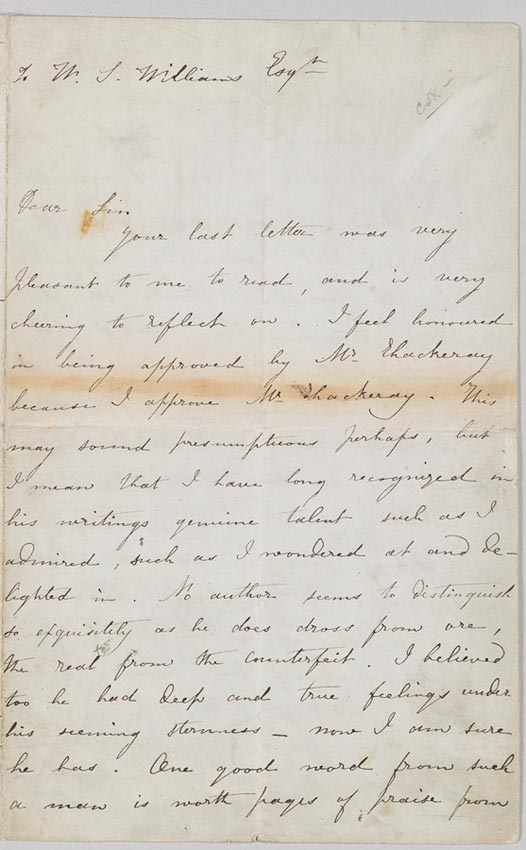

Letter to William S. Williams, 28 October 1847, pages 2–3

Letter to William S. Williams of Smith, Elder & Co., dated Haworth, 28 October 1847

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

In this letter to William S. Williams of the firm that had published Jane Eyre, Brontë reacted to some of the early reviews of her first published novel. She defended her portrayal of Helen Burns, a virtuous child who dies in Jane’s arms. Helen was, Brontë implied, a fictional reimagining of her own sister Maria, who had died at the age of eleven after falling ill at the Clergy Daughters’ School.

ordinary judges.

You are right in having faith in the reality of Helen Burns’s character: she was real enough: I have exaggerated nothing there: I abstained from recording much that I remember respecting her, lest the narrative should sound incredible. Knowing this, I could not but smile at the quiet, self-complacent dogmatism with which one of the journals lays it down that “such creations as Helen Bums are very beautiful but very untrue.”

The plot of “Jane Eyre[”] may be a hackneyed one; Mr. Thackeray remarks that it is familiar to him; but having read comparatively few novels, I never chanced to meet with it, and I thought it original –. The critic of the Athenaeum’s work, I had not had the good fortune to hear of.

The Weekly Chronicle seems inclined to identify me with Mrs Marsh. I never had the pleasure of perusing a line of Mrs Marsh’s in my life – but I wish very much to read her works and shall profit by the first opportunity of doing so. I hope I shall not find I have been an unconscious imitator.

I would still endeavour to keep my expectations low respecting the ultimate success of “Jane Eyre”; but my desire that it should succeed augments – for you have taken much trouble about the work, and it would grieve me seriously if your active efforts should be baffled and your sanguine hopes disappointed: excuse me if I again remark that I fear they are rather too sanguine; it would be better to moderate them. What will the critics

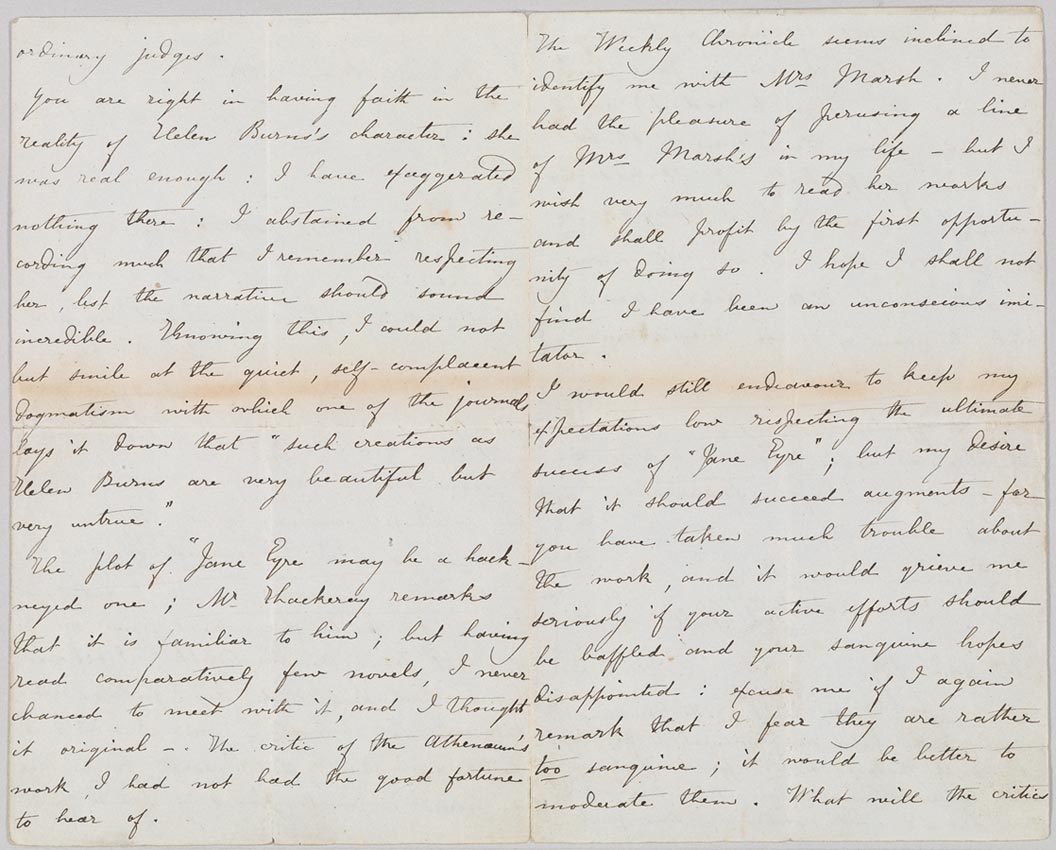

Letter to William S. Williams, 28 October 1847, page 4

Letter to William S. Williams of Smith, Elder & Co., dated Haworth, 28 October 1847

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

In this letter to William S. Williams of the firm that had published Jane Eyre, Brontë reacted to some of the early reviews of her first published novel. She defended her portrayal of Helen Burns, a virtuous child who dies in Jane’s arms. Helen was, Brontë implied, a fictional reimagining of her own sister Maria, who had died at the age of eleven after falling ill at the Clergy Daughters’ School.

of the Monthly Reviews and Magazines be likely to see in “Jane Eyre” (if indeed they deign to read it) which will win from them even a stinted modicum of approbation? It has no learning, no research, it discusses no subject of public interest. A mere domestic novel will I fear seem trivial to men of large views and solid attainments.

Still – efforts so energetic and indefatigable as yours ought to realize a result in some degree favourable, and I trust they will.

I remain, dear Sir

Yours respectfully

C Bell.

Octbr 28th / 47

I have just recd. “the Tablet” and the “Morning Advertiser” – neither paper seems inimical to the book – but I see it produces a very different effect – on different natures. I was amused at the analysis in the Tablet – it is oddly expressed in some parts – I think the critic did not always seize my meaning – he speaks for instance of “Jane’s inconceivable alarm at Mr. Rochester’s repelling manner – I do not remember that

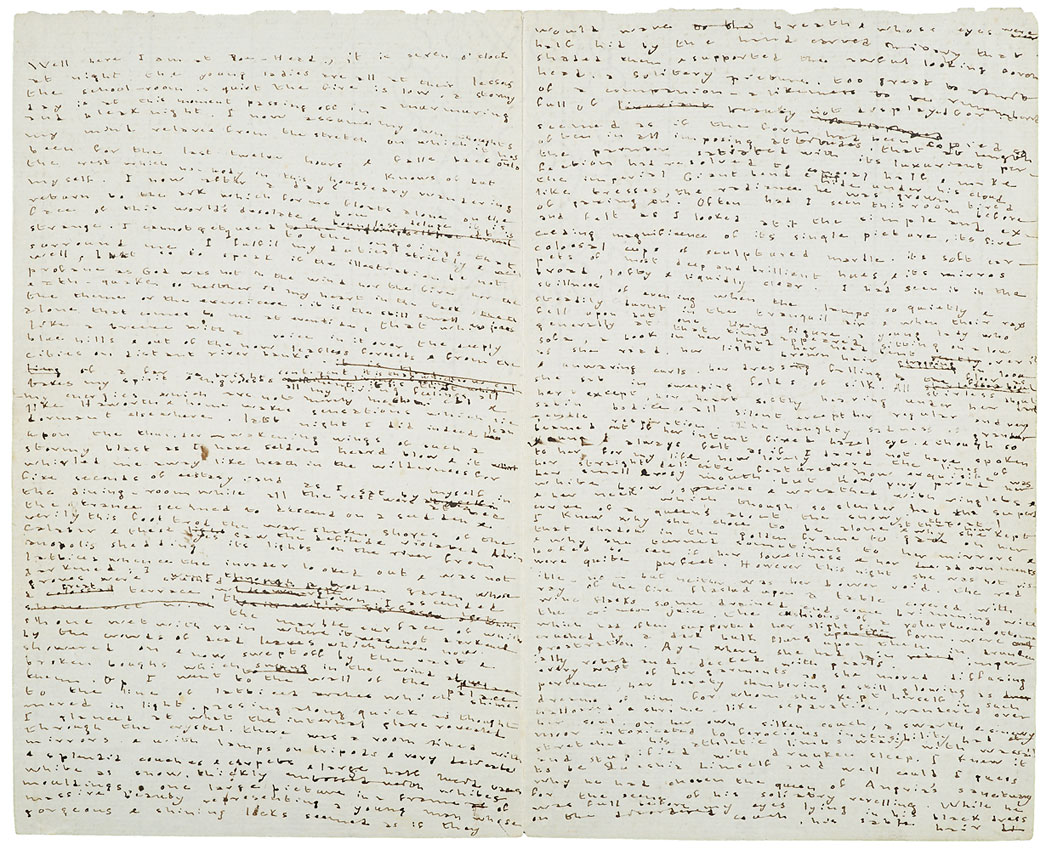

2. Manuscript, 4 February 1836

“Well here I am at Roe Head. . . .”

Manuscript, written at the Roe Head school, 4 February 1836

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

When she was nineteen, Brontë returned to the Roe Head school as a teacher. Though she had thrived as a student and made several lifelong friends there, she chafed in her new role. Taking up this folded sheet of paper one evening after “a day’s weary wandering,” she expressed her feelings of alienation then moved seamlessly into a fictional fantasy tinged with eroticism. She described herself as a voyeur peering through the windows of an exotic palace and watching Quashia Qamina, a character from her stories, reclining drunk and disheveled in a rival queen’s chamber.

Well, here I am at Roe-Head. It is seven o’clock at night, the young ladies are all at their lessons, the school-room is quiet, the fire is low, a stormy day is at this moment passing off in a murmuring and bleak night. I now assume my own thoughts; my mind relaxes from the stretch on which it has been for the last twelve hours & falls back onto the rest which no-body in this house knows of but myself.

I now, after a day’s weary wandering, return to the ark which for me floats alone on the face of this world’s desolate & boundless deluge. It is strange. I cannot get used to the ongoings that surround me. I fulfil my duties strictly & well, yet, so to speak, if the illustration be not profane, as God was not in the wind, nor the fire, nor the earth-quake, so neither is my heart in the task, the theme or the exercise. It is the still small voice alone that comes to me at eventide, that which like a breeze with a voice in it [comes] over the deeply blue hills & out of the now leafless forests & from the cities on distant river banks of a far & bright continent. It is that which wakes my spirit & engrosses all my living feelings, all my energies which are not merely mechanical, & like Haworth & home, wakes sensations which lie dormant elsewhere.

Last night I did indeed lean upon the thunder-wakening wings of such a stormy blast as I have seldom heard blow, & it whirled me away like heath in the wilderness for five seconds of ecstasy, and as I sat by myself in the dining-room while all the rest were at tea the trance seemed to descend on a sudden, & verily this foot trod the war-shaken shores of the Calabar & these eyes saw the defiled & violated Adrianopolis shedding its lights on the river from lattices whence the invader looked out & was not darkened.

I went through a trodden garden whose groves were crushed down. I ascended a great terrace, the marble surface of which shone wet with rain where it was not darkened by the mounds of dead leaves which were now showered on & now swept off by the vast & broken boughs which swung in the wind above them.

Up I went to the wall of the palace to the line of latticed arches which shimmered in light, passing along quick as thought, I glanced at what the internal glare revealed through the crystal. There was a room lined with mirrors & with lamps on tripods, & very darkened, & splendid couches & carpets & large half lucid vases white as snow, thickly embossed with whiter mouldings, & one large picture in a frame of massive beauty representing a young man whose gorgeous & shining locks seemed as if they would wave on the breath & whose eyes were half hid by the hand carved in ivory that shaded them & supported the awful looking coron[al?] head—a solitary picture, too great to admit of a companion—a likeness to be remembered full of beauty, not displayed, for it seemed as if the form had been copied so often in all imposing attitudes, that at length the painter, satiated with its luxuriant perfection, had resolved to conceal half & make the imperial Giant bend & hide under his cloudlike tresses, the radiance he was grown tired of gazing on.

Often had I seen this room before and felt, as I looked at it, the simple and exceeding magnificence of its single picture, its five colossal cups of sculptured marble, its soft carpets of most deep and brilliant hues, & its mirrors, broad, lofty, & liquidly clear. I had seen it in the stillness of evening when the lamps so quietly & steadily burnt in the tranquil air, & when their rays fell upon but one living figure, a young lady who generally at that time appeared sitting on a low sofa, a book in her hand, her head bent over it as she read, her light brown hair dropping in loose & unwaving curls, her dress falling to the floor as she sat in sweeping folds of silk. All stirless about her except her heart, softly beating under her satin bodice & all silent except her regular and very gentle respiration.

The haughty sadness of grandeur beamed out of her intent fixed hazel eye, & though so young, I always felt as if I dared not have spoken to her for my life, how lovely were the lines of her small & rosy mouth, but how very proud her white brow, spacious & wreathed with ringlets, & her neck, which, though so slender, had the superb curve of a queen’s about the snowy throat. I knew why she chose to be alone at that hour, & why she kept that shadow in the golden frame to gaze on her, & why she turned sometimes to her mirrors & looked to see if her loveliness & her adornments were quite perfect.

However this night she was not visible—no—but neither was her bower void. The red ray of the fire flashed upon a table covered with wine flasks, some drained and some brimming with the crimson juice. The cushions of a voluptuous ottoman which had often supported her slight, fine form were crushed by a dark bulk flung upon them in drunken prostration. Aye, where she had lain imperially robed and decked with pearls, every waft of her garments as she moved diffusing perfume, her beauty slumbering & still glowing as dreams of him for whom she kept herself in such hallowed & shrine-like separation wandered over her soul, on her own silken couch, a swarth & sinewy moor intoxicated to ferocious insensibility had stretched his athletic limbs, weary with wassail and stupefied with drunken sleep.

I knew it to be Quashia himself, and well could I guess why he had chosen the queen of Angria’s sanctuary for the scene of his solitary revelling. While he was full before my eyes, lying in his black dress on the disordered couch, his sable hair dishevelled on his forehead, his tusk-like teeth glancing vindictively through his parted lips, his brown complexion flushed with wine, & his broad chest heaving wildly as the breath issued in spurts from his distended nostrils, while I watched the fluttering of his white shirt ruffles starting through the more than half-unbuttoned waistcoat, & beheld the expression of his Arabian countenance savagely exulting even in sleep, Quashia triumphant Lord in the halls of Zamorna! in the bower of Zamorna’s lady! while this apparition was before me, the dining-room door opened and Miss W[ooler] came in with a plate of butter in her hand. “A very stormy night my dear!” said she. “It is ma’am,” said I.

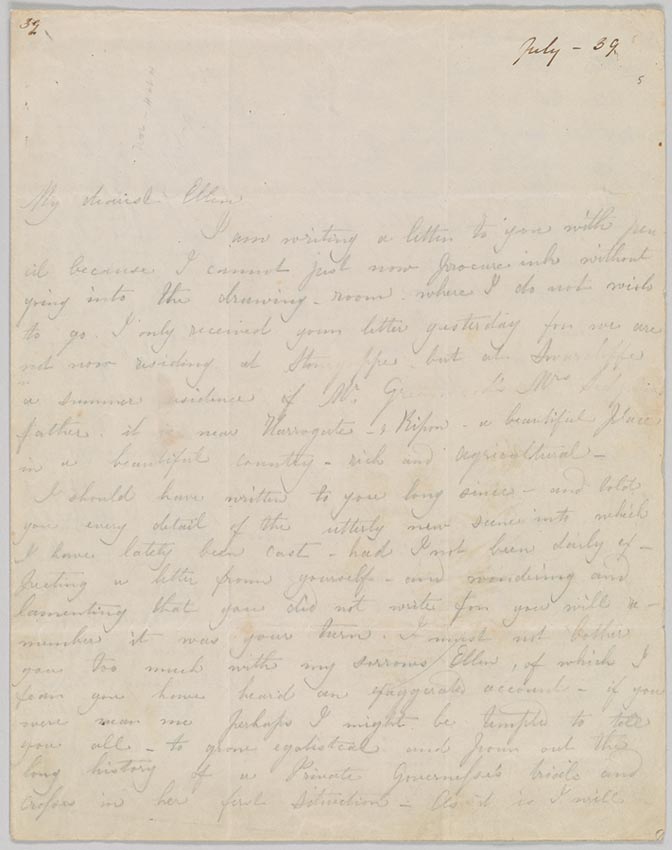

3. Letter to Ellen Nussey, 30 June 1839, page 1

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Swarcliffe, Harrogate, 30 June 1839

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë spent a few months during the summer of 1839 caring for what she called the “riotous, perverse, unmanageable cubs” of the Sidgwick family. Not only did she detest the work, she felt awkwardly marginal within the family circle. She was so ill at ease that she preferred to write this letter (to her close friend Ellen) in pencil rather than venture into the drawing room to procure some ink.

My dearest Ellen

I am writing a letter to you with pencil because I cannot just now procure ink without going into the drawing-room – where I do not wish to go. I only received your letter yesterday for we are not now residing at Stonegappe – but at Swarcliffe a summer residence of Mr Greenwood’s Mrs Sidgwick’s father – it is near Harrogate – & Ripon – a beautiful place in a beautiful country – rich and agricultural –

I should have written to you long since – and told you every detail of the utterly new scene into which I have lately been cast – had I not been daily expecting a letter from yourself – and wondering and lamenting that you did not write for you will remember it was your turn. I must not bother you too much with my sorrows Ellen, of which I fear you have heard an exaggerated account – if you were near me perhaps I might be tempted to tell you all – to grow egotistical and pour out the long history of a Private Governesse’s trials and crosses in her first Situation – As it is I will

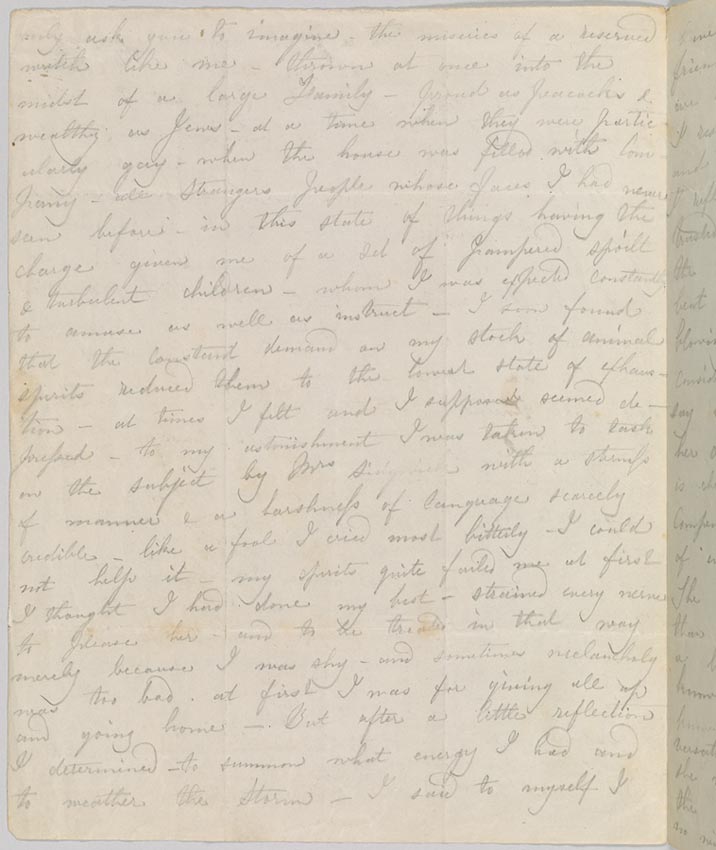

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 30 June 1839, page 2

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Swarcliffe, Harrogate, 30 June 1839

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë spent a few months during the summer of 1839 caring for what she called the “riotous, perverse, unmanageable cubs” of the Sidgwick family. Not only did she detest the work, she felt awkwardly marginal within the family circle. She was so ill at ease that she preferred to write this letter (to her close friend Ellen) in pencil rather than venture into the drawing room to procure some ink.

only ask you to imagine the miseries of a reserved wretch like me – thrown at once into the midst of a large Family – proud as peacocks & wealthy as Jews – at a time when they were particularly gay – when the house was filled with Company – all Strangers [–] people whose faces I had never seen before – in this state of things having the charge given me of a set of pampered spoilt & turbulent children – whom I was expected constantly to amuse as well as instruct – I soon found that the constant demand on my stock of animal spirits reduced them to the lowest state of exhaustion – at times I felt and I suppose seemed depressed – to my astonishment I was taken to task on the subject by Mrs Sidgwick with a stern[n]ess of manner & a harshness of language scarcely credible – like a fool I cried most bitterly – I could not help it – my spirits quite failed me at first [–] I thought I had done my best – strained every nerve to please her – and to be treated in that way merely because I was shy – and sometimes melancholy was too bad. At first I was for giving all up and going home –. But after a little reflection I determined – to summon what energy I had and to weather the Storm – I said to myself I

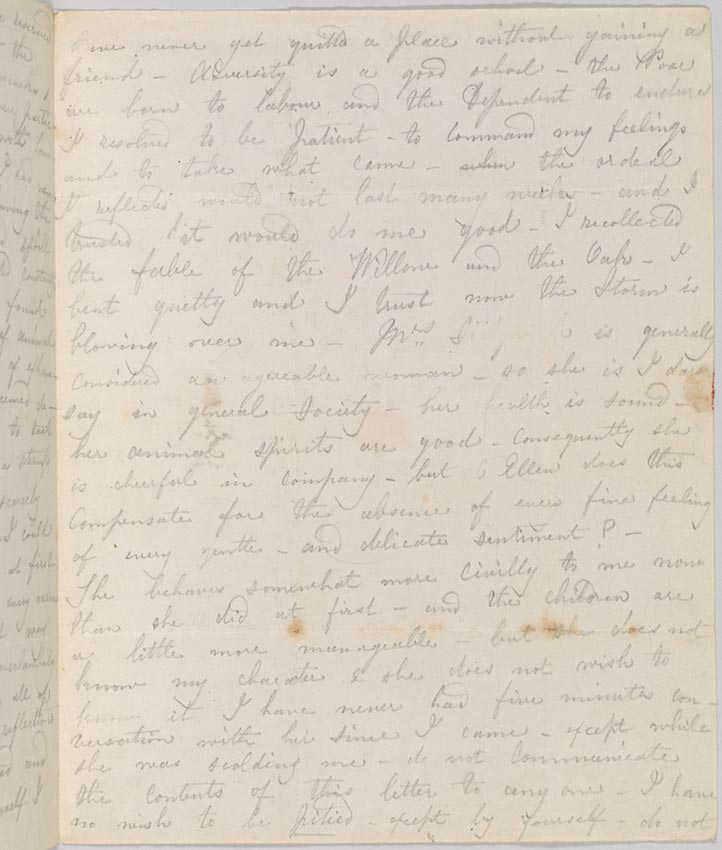

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 30 June 1839, page 3

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Swarcliffe, Harrogate, 30 June 1839

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë spent a few months during the summer of 1839 caring for what she called the “riotous, perverse, unmanageable cubs” of the Sidgwick family. Not only did she detest the work, she felt awkwardly marginal within the family circle. She was so ill at ease that she preferred to write this letter (to her close friend Ellen) in pencil rather than venture into the drawing room to procure some ink.

have never yet quitted a place without gaining a friend – Adversity is a good school – the Poor are born to labour and the Dependent to endure[.] I resolved to be patient – to command my feelings and to take what came – when the ordeal I reflected would not last many weeks – and I trusted it would do me good – I recollected the fable of the Willow and the Oak – I bent quietly and I trust now the Storm is blowing over me – Mrs Sidgwick is generally considered an agreeable woman – so she is I daresay in general Society – her health is sound – her animal spirits are good – consequently she is cheerful in company – but O Ellen does this compensate for the absence of every fine feeling of every gentle – and delicate sentiment? –

She behaves somewhat more civilly to me now than she did at first – and the children are a little more manageable – but she does not know my character & she does not wish to know it[.] I have never had five minutes conversation with her since I came – except while she was scolding me – do not communicate the contents of this letter to any one – I have no wish to be pitied – except by yourself – do not

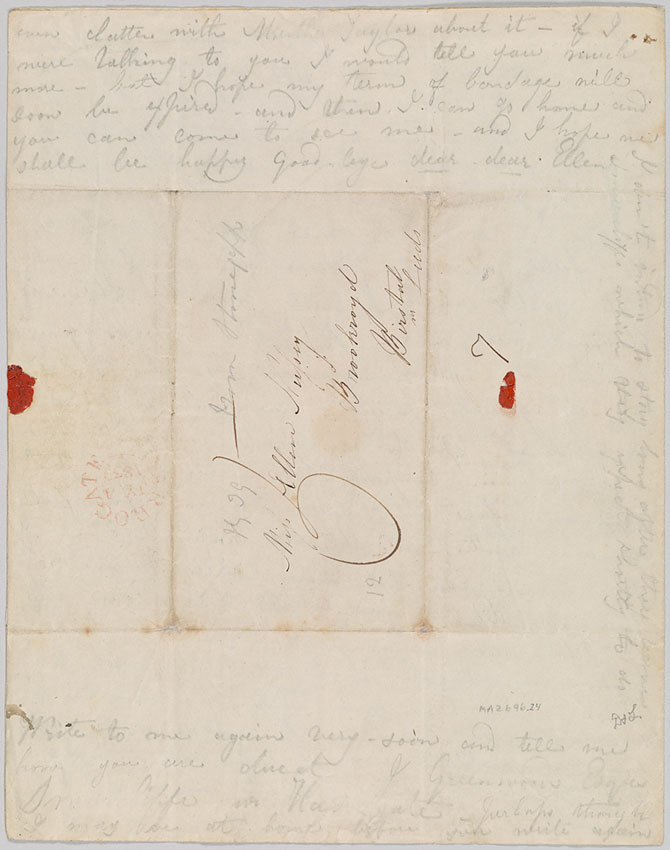

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 30 June 1839, page 4

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Swarcliffe, Harrogate, 30 June 1839

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë spent a few months during the summer of 1839 caring for what she called the “riotous, perverse, unmanageable cubs” of the Sidgwick family. Not only did she detest the work, she felt awkwardly marginal within the family circle. She was so ill at ease that she preferred to write this letter (to her close friend Ellen) in pencil rather than venture into the drawing room to procure some ink.

even chatter with Martha Taylor about it – if I were talking to you I would tell you much more – but I hope my term of bondage will soon be expired – and then I can go home and you can come to see me – and I hope we shall be happy[.] Good-bye dear – dear Ellen

Write to me again very – soon and tell me how you are [–] direct J Greenwoods Esqre Swarcliffe nr Harrogate – perhaps though I may be at home before you write again I don’t intend to stay long after they leave Swarcliffe which they expect shortly to do

[the letter is unsigned]

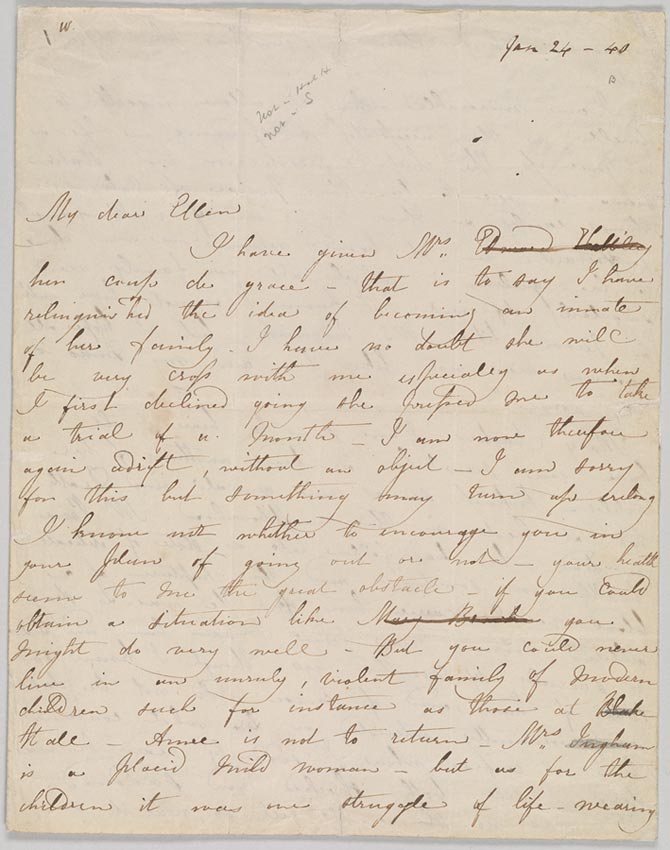

4. Letter to Ellen Nussey, 24 January 1840, page 1

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 24 January 1840

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few months after she left the Sidgwick family’s employ, Brontë wrote this letter to her friend Ellen to let her know that she had just turned down a new job offer. Susanna Halliley of Leeds, a Brontë family acquaintance, had advertised for a churchgoing young lady of “amiable disposition, and some experience, willing to make herself generally useful, and competent to teach Music, French and Drawing.” The letter, which Brontë wrote in a moment of ill humor as she contemplated an unappealing future, shows evidence of her eventual fame: there is a hole in the paper where someone (presumably Ellen, later in her life) has clipped out Brontë’s signature for an autograph seeker.

My dear Ellen

I have given Mrs Edward Halliley her coup de grace – that is to say I have relinquished the idea of becoming an inmate of her family – I have no doubt she will be very cross with me especially as when I first declined going she pressed me to take a trial of a month – I am now therefore again adrift, without an object – I am sorry for this but something may tum up erelong.

I know not whether to encourage you in your plan of going out or not – your health seems to me the great obstacle – if you could obtain a situation like Mary Brooke you might do very well – But you could never live in an unruly, violent family of modern children such for instance as those at Blake Hall – Anne is not to return – Mrs Ingham is a placid mild woman – but as for the children it was one struggle of life-wearing

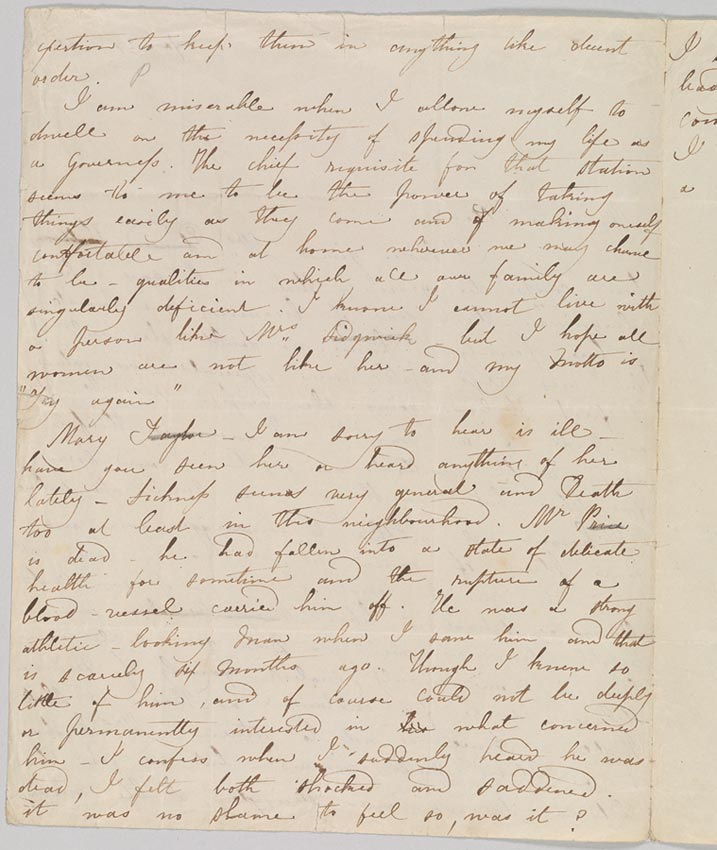

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 24 January 1840, page 2

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 24 January 1840

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few months after she left the Sidgwick family’s employ, Brontë wrote this letter to her friend Ellen to let her know that she had just turned down a new job offer. Susanna Halliley of Leeds, a Brontë family acquaintance, had advertised for a churchgoing young lady of “amiable disposition, and some experience, willing to make herself generally useful, and competent to teach Music, French and Drawing.” The letter, which Brontë wrote in a moment of ill humor as she contemplated an unappealing future, shows evidence of her eventual fame: there is a hole in the paper where someone (presumably Ellen, later in her life) has clipped out Brontë’s signature for an autograph seeker.

exertion to keep them in anything like decent order.

I am miserable when I allow myself to dwell on the necessity of spending my life as a Governess. The chief requisite for that station seems to me to be the power of taking things easily as they come and of making oneself comfortable and at home wherever we may chance to be – qualities in which all our family are singularly deficient. I know I cannot live with a person like Mrs Sidgwick – but I hope all women are not like her – and my motto is “Try again”

Mary Taylor – I am sorry to hear is ill – have you seen her or heard anything of her lately – Sickness seems very general and Death too at least in this neighbourhood. Mr Price is dead – he had fallen into a state of delicate health for sometime and the rupture of a blood-vessel carried him off. He was a strong athletic-looking man when I saw him and that is scarcely six months ago. Though I knew so little of him, and of course could not be deeply or permanently interested in his what concerned him – I confess when I suddenly heard he was dead, I felt both shocked and saddened. It was no shame to feel so, was it?

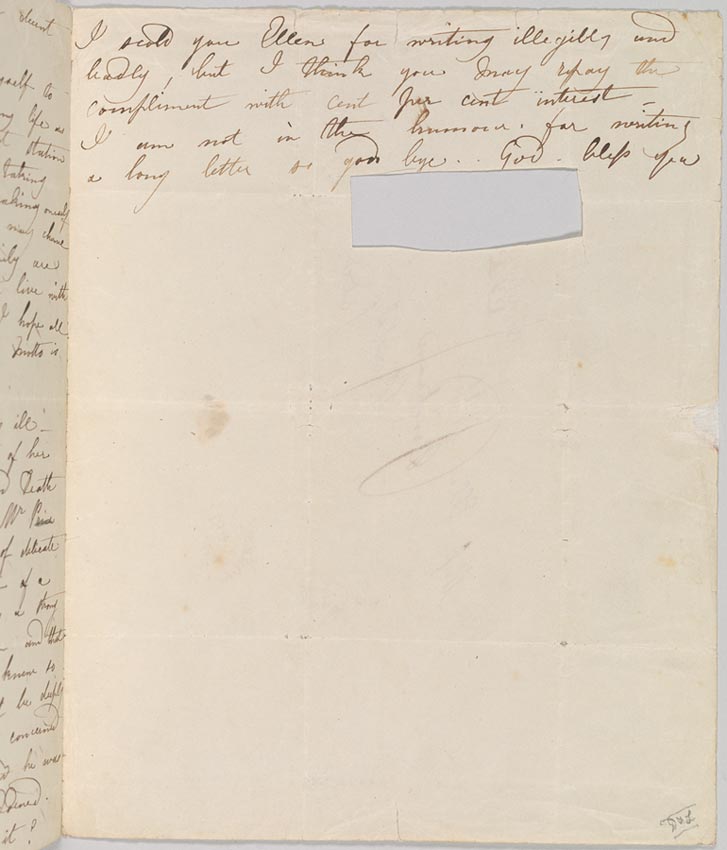

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 24 January 1840, page 3

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 24 January 1840

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few months after she left the Sidgwick family’s employ, Brontë wrote this letter to her friend Ellen to let her know that she had just turned down a new job offer. Susanna Halliley of Leeds, a Brontë family acquaintance, had advertised for a churchgoing young lady of “amiable disposition, and some experience, willing to make herself generally useful, and competent to teach Music, French and Drawing.” The letter, which Brontë wrote in a moment of ill humor as she contemplated an unappealing future, shows evidence of her eventual fame: there is a hole in the paper where someone (presumably Ellen, later in her life) has clipped out Brontë’s signature for an autograph seeker.

I scold you Ellen for writing illegibly and badly, but I think you may repay the compliment with cent per cent interest – I am not in the humour for writing a long letter so good bye. God bless you

[signature cut out]

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 24 January 1840, page 4

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 24 January 1840

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few months after she left the Sidgwick family’s employ, Brontë wrote this letter to her friend Ellen to let her know that she had just turned down a new job offer. Susanna Halliley of Leeds, a Brontë family acquaintance, had advertised for a churchgoing young lady of “amiable disposition, and some experience, willing to make herself generally useful, and competent to teach Music, French and Drawing.” The letter, which Brontë wrote in a moment of ill humor as she contemplated an unappealing future, shows evidence of her eventual fame: there is a hole in the paper where someone (presumably Ellen, later in her life) has clipped out Brontë’s signature for an autograph seeker.

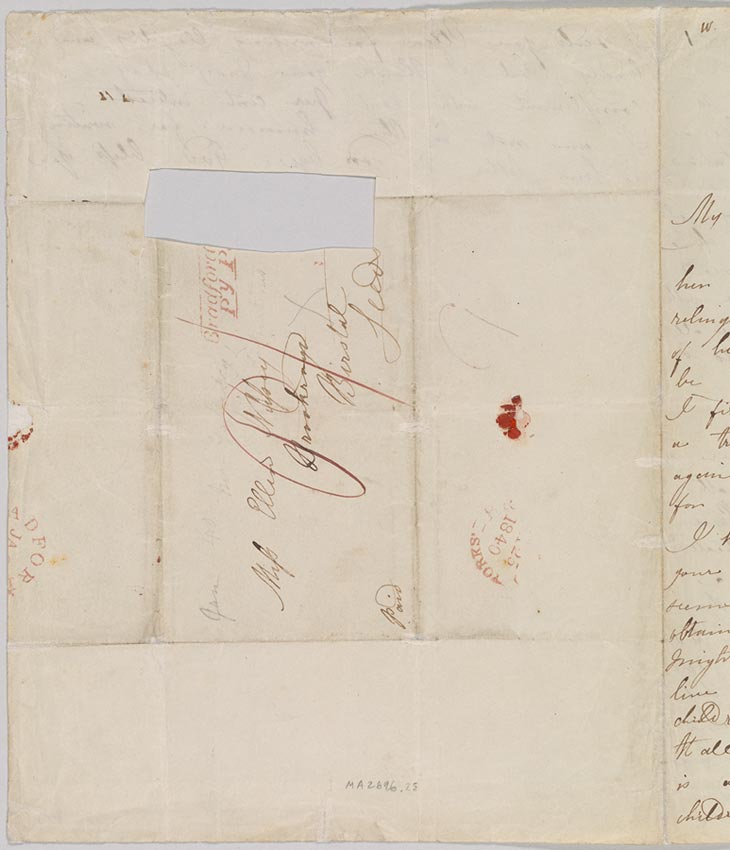

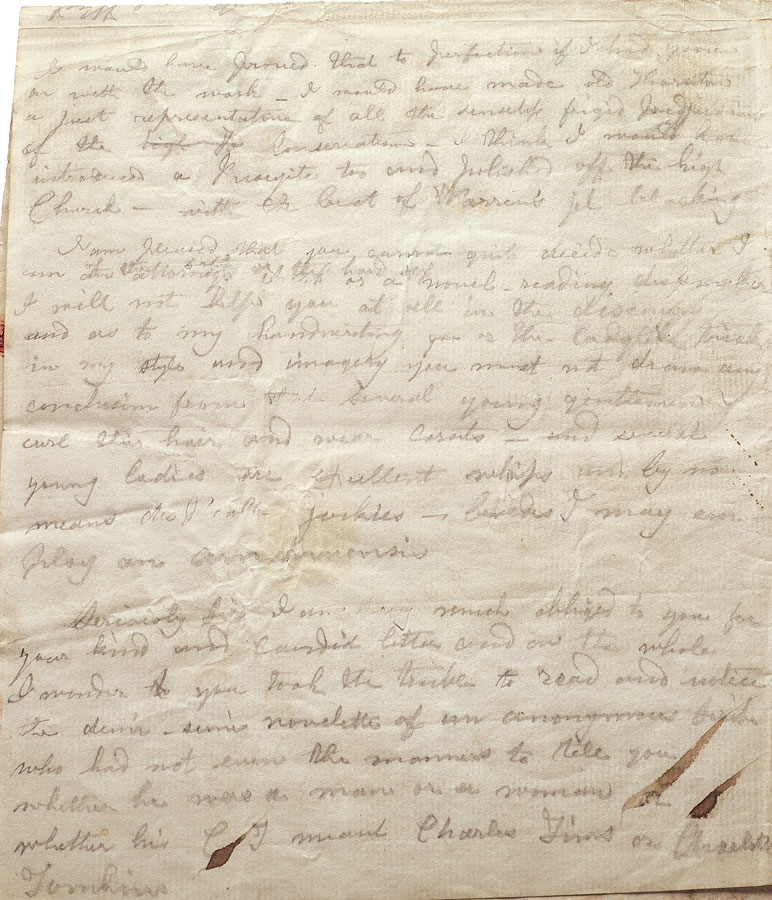

5. Draft of a letter to Hartley Coleridge, December 1840

Draft of a letter to Hartley Coleridge, dated Haworth, December 1840

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

In 1840, Brontë sent a manuscript of her work in progress to the poet Hartley Coleridge, asking his advice on pursuing a writing career. She decided to keep her identity – and sex – a secret. Coleridge looked over the manuscript, wrapped it up in this sheet of paper, and returned it to C. T. (the pseudonym Brontë had chosen) at the parsonage in Haworth. Coleridge’s accompanying letter does not survive, but it did not, evidently, contain a rave review.

Brontë turned the wrapper over and used pencil to draft a reply to Coleridge. She thanked him for taking the time “to read and notice the demi-semi novelette of an anonymous Scribe who had not even the manners to tell you whether he was a man or a woman or whether his C T meant Charles Tims or Charlotte Tomkins.” At the same time, Brontë challenged Coleridge to confront his assumptions about gender and authorship. (She later revised and recopied the letter; what is shown here is her first draft.)

Authors are generally very tenacious of their productions but I am not so attached to this production but that I can give it up without much distress

You say the affair is begun on the scale of a three volume novel I assure you Sir you calculate very moderately – for if I had materials in my head I daresay for half a dozen – No doubt if I had gone on I should have made a Sir Charles Grandison Richardsonian concern of it Mr West should have been my Sir Charles Grandison – Percy my Mr B – and the ladies you should have represented – Pamela, Clarissa Harriet Byron &c. Of the one I have sketched – it is very edifying and profitable to create a little world out of your own brain – and people it with inhabitants who are like so many Melchisedecs & have no father nor mother but your own imagination – by daily conversation with these individuals – by interesting yourself in their family affairs and enquiring into their histories you acquire a tone of mind admirably calculated to ennable you to cut a solid & respectable figure in practical life.

The ideal and the actual are no longer distinct notions in your mind but amalgamate in an interesting medley from whence result looks, thoughts and manners bordering on the idiotic

I am sorry I did not exist si fifty or sixty years ago when the lady’s magazine was flourishing like a green-bay tree – in that case I should n I make no doubt my aspirations after literary fame would have met with due encouragement – and I should have had the pleasure of introducing Messrs Percy & West into the very best society – and recording all their sayings and doings in double-columned-close-printed pages side by side with Count Albert or the haunted castle – Evelina or the Recluse of the lake – Sigismund or the Nunnery & many other equally effective and brilliant productions – You see Sir I have read the lady’s Magazine and know something of its contents – though I will not be quite certain of the correctness of the titles I have quoted – I recollect when I was a child getting hold of some antiquated odd volumes and reading them by stealth with the most exquisite pleasure.

You give a correct description of the patient Grizzles of those days – my Aunt was one of them and to this day she thinks the tales of the Lady’s Magazine infinitely superior to any trash of Modern literature. So do I for I read them in childhood and childhood has a very strong [illeg.] of admiration but a very weak one of Criticism

The idea of applying to a ‘regular’ Novel-publisher and seeing Mr West and Mr Percy at full-length in three vols is very tempting – but I think on the whole from what you say I had better lock up this precious manuscript – wait patiently till I meet with some Maecenas who shall discern and encourage my rising talent – & meantime bind myself apprentice to a chemist & druggist if I am a young gentleman or to Mantua maker & milliner if I am a young lady

You say something about my politics – intimating that I you suppose me to be a high Tory – belonging to the same party which claims for its head the his Serene highness the prince of powers of the air

I would have proved that to perfection if I had gone on with the work – I would have made old Thornton a just representative of all the senseless frigid prejudices of the high T Conservatism – I think I would have introduced a Puseyite too and polished off the high Church – with the best of Warren’s jet blacking

I am pleased that you cannot quite decide whether I am of the soft or the hard sex an attorney’s clerk or a novel-reading dressmaker I will not help you at all in the discovery and as to my handwriting you with the ladylike tricks in my style and imagery you must not draw any conclusion from that – Several young gentlemen curl their hair and wear corsets – and several young ladies are excellent whips and by no means despicable jockies – besides I may employ an amanuensis

Seriously Sir I am very much obliged to you for your kind and candid letter and on the whole I wonder to you took the trouble to read and notice the demi-semi novelette of an anonymous Scribe who had not even the manners to tell you whether he was a man or a woman whether his C T meant Charles Tims or Charlotte Tompkins

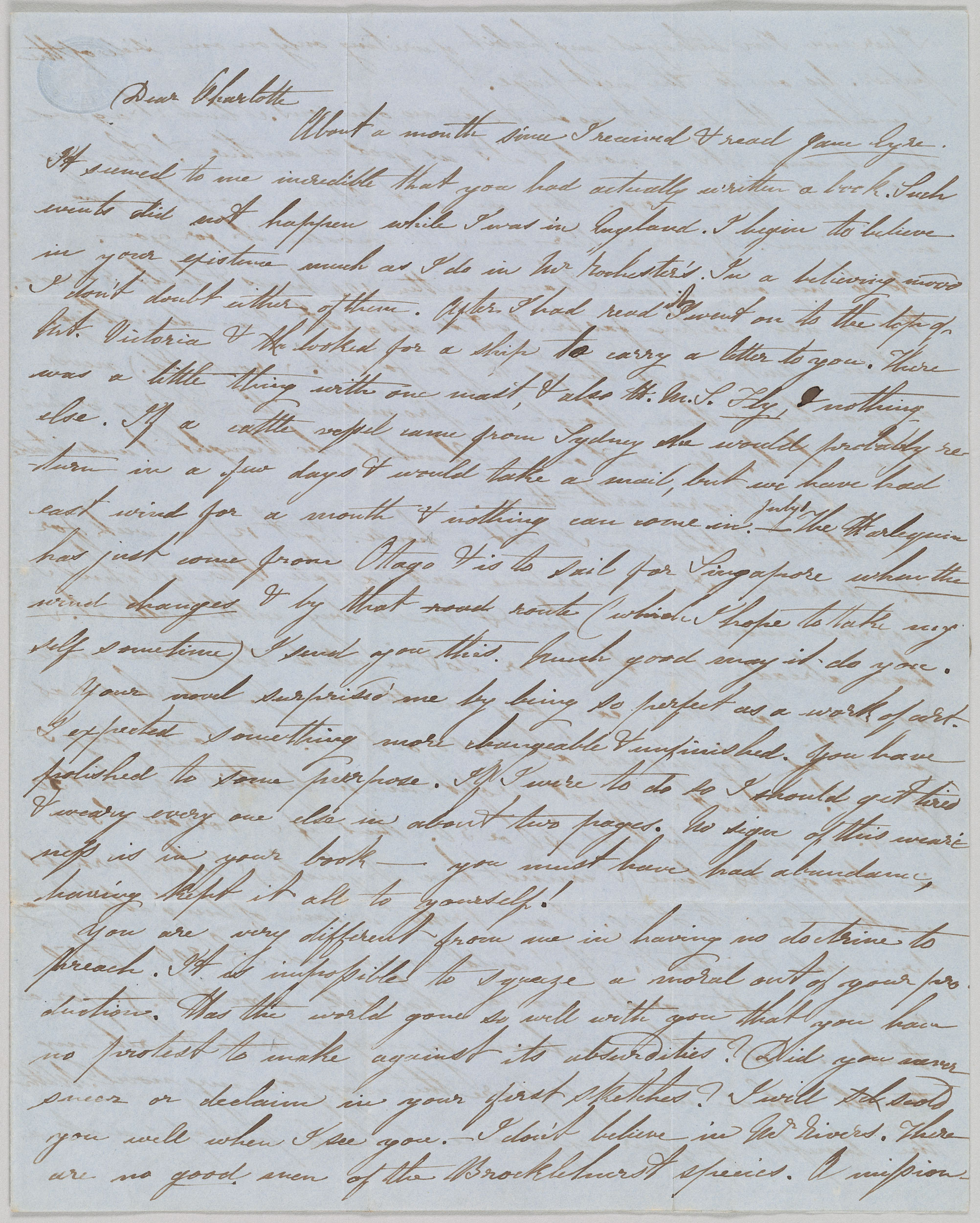

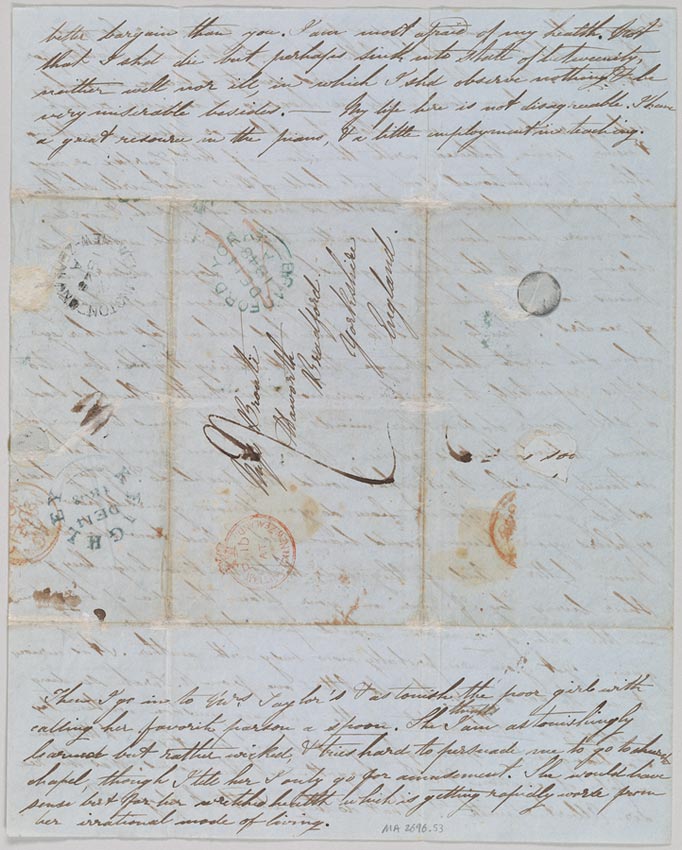

6. Letter to Charlotte Brontë, 24 July 1848, page 1

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, dated Wellington, New Zealand, 24 July 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

When she published her first novel, Jane Eyre, in 1847, Charlotte Brontë told almost no one. But she did send a copy, along with Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, to her good friend Mary Taylor in Wellington, New Zealand. Taylor responded with this affectionate letter. By the time it arrived in Yorkshire (five months after she had dispatched it from Wellington), Emily was near death and “Currer Bell” was a literary star.

Dear Charlotte

About a month since I received & read Jane Eyre. It seemed to me incredible that you had actually written a book. Such events did not happen while I was in England. I begin to believe in your existence much as I do in Mr Rochester’s. In a believing mood I don’t doubt either of them. After I had read it I went on to the top of Mt. Victoria & looked for a ship to carry a letter to you. There was a little thing with one mast, & also H.M.S. Fly & nothing else. If a cattle vessel came from Sydney she would probably return in a few days & would take a mail, but we have had east wind for a month & nothing can come in.—July 1. The Harlequin has just come from Otago & is to sail for Singapore when the wind changes & by that road route (which I hope to take myself sometime) I send you this. Much good may it do you.

Your novel surprised me by being so perfect as a work of art. I expected something more changeable & unfinished. You have polished to some purpose. If I were to do so I should get tired & weary every one else in about two pages. No sign of this weariness is in your book—you must have had abundance, having kept it all to yourself!

You are very different from me in having no doctrine to preach. It is impossible to squeeze a moral out of your production. Has the world gone so well with you that you have no protest to make against its absurdities? Did you never sneer or declaim in your first sketches? I will scold you well when I see you.—I don’t believe in Mr Rivers. There are no good men of the Brocklehurst species. A mission-

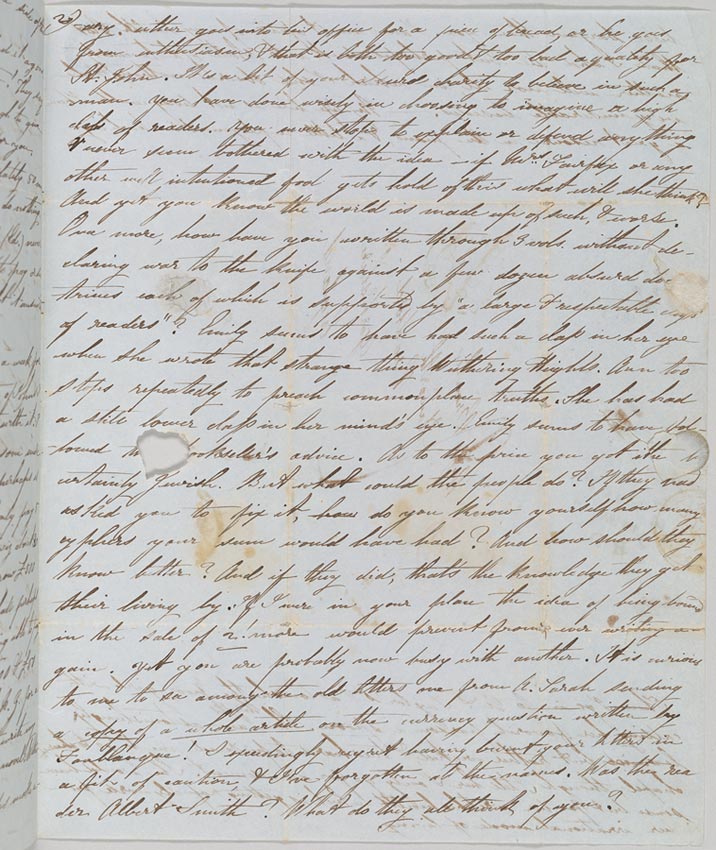

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, 24 July 1848, page 2

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, dated Wellington, New Zealand, 24 July 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

When she published her first novel, Jane Eyre, in 1847, Charlotte Brontë told almost no one. But she did send a copy, along with Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, to her good friend Mary Taylor in Wellington, New Zealand. Taylor responded with this affectionate letter. By the time it arrived in Yorkshire (five months after she had dispatched it from Wellington), Emily was near death and “Currer Bell” was a literary star.

-ary either goes into his office for a piece of bread, or he goes from enthusiasm, & that is both too good & too bad a quality for St. John. It’s a bit of your absurd charity to believe in such a man. You have done wisely in choosing to imagine a high class of readers. You never stop to explain or defend anything & never seem bothered with the idea—if Mrs. Fairfax or any other well intentioned fool gets hold of this what will she think? And yet you know the world is made up of such, & worse. Once more, how have you written through 3 vols. without declaring war to the knife against a few dozen absurd doctrines each of which is supported by “a large & respectable class of readers”? Emily seems to have had such a class in her eye when she wrote that strange thing Wuthering Heights. Ann[e] too stops repeatedly to preach commonplace truths. She has had a still lower class in her mind’s eye. Emily seems to have followed t[he] [b]ookseller’s advice. As to the price you got it [was] certainly Jewish. But what could the people do? lf they had asked you to fix it, how do you know yourself how many cyphers your sum would have had? And how should they know better? And if they did, that’s the knowledge they get their living by. If I were in your place the idea of being bound in the sale of 2! more would prevent [me]from ever writing again. Yet you are probably now busy with another. It is curious to me to see among the old letters one from A[unt] Sarah sending a copy of a whole article on the currency question written by Fonblanque! I exceedingly regret having burnt your letters in a fit of caution, & I’ve forgotten all the names. Was the reader Albert Smith? What do they all think of you?

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, 24 July 1848, page 3

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, dated Wellington, New Zealand, 24 July 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

When she published her first novel, Jane Eyre, in 1847, Charlotte Brontë told almost no one. But she did send a copy, along with Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, to her good friend Mary Taylor in Wellington, New Zealand. Taylor responded with this affectionate letter. By the time it arrived in Yorkshire (five months after she had dispatched it from Wellington), Emily was near death and “Currer Bell” was a literary star.

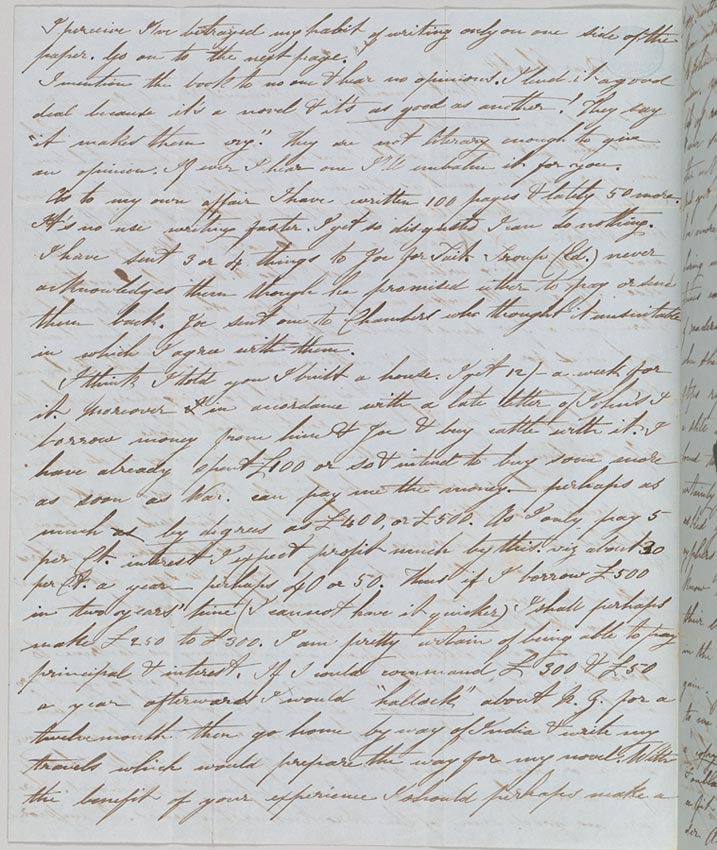

I perceive I’ve betrayed my habit of writing only on one side of the paper. Go onto the next page.

I mention the book to no one & hear no opinions. I lend it a good deal because it’s a novel & it’s as good as another! They say “it makes them cry.” They are not literary enough to give an opinion. If ever I hear one I’ll embalm it for you.

As to my own affair I have written 100 pages & lately 50 more. It’s no use writing faster. I get so disgusted I can do nothing. I have sent 3 or 4 things to Joe for Tait. Troup (Ed.) never acknowledges them though he promised either to pay or send them back. Joe sent one to Chambers who thought it unsuitable in which I agree with them.

I think I told you I built a house. I get 12/– a week for it. Moreover I in accordance with a late letter of John’s I borrow money from him & Joe & buy cattle with it. I have already spent £100 or so & intend to buy some more as soon as War[ing] can pay me the money. —perhaps as much as by degrees as £400, or £500. As I only pay 5 per Ct. interest I expect [to] profit much by this. viz about 30 per Ct. a year—perhaps 40 or 50. Thus if I borrow £500 in two years’ time (I cannot have it quicker) I shall perhaps make £250 to £300. I am pretty certain of being able to pay principal & interest. If I could command £300 & £50 a year afterwards I would “hallock” about N.Z. for a twelvemonth then go home by way of India & write my travels which would prepare the way for my novel. With the benefit of your experience I should perhaps make a

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, 24 July 1848, page 4

Letter to Charlotte Brontë, dated Wellington, New Zealand, 24 July 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

When she published her first novel, Jane Eyre, in 1847, Charlotte Brontë told almost no one. But she did send a copy, along with Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, to her good friend Mary Taylor in Wellington, New Zealand. Taylor responded with this affectionate letter. By the time it arrived in Yorkshire (five months after she had dispatched it from Wellington), Emily was near death and “Currer Bell” was a literary star.

better bargain than you. I am most afraid of my health. Not that I shd die but perhaps sink into state of betweenity, neither well nor ill, in which I shd observe nothing & be very miserable besides. —My life here is not disagreeable. I have a great resource in the piano, & a little employment in teaching.

Then I go to Mrs. Taylor’s & astonish the poor girl with calling her favorite parson a spoon. She thinks I am astonishingly learned but rather wicked, & tries hard to persuade me to go to church chapel, though I tell her I only go for amusement. She would have sense but for her wretched health which is getting rapidly worse from her irrational mode of living.

[letter continues on a separate sheet in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library] I can hardly explain to you the queer feeling of living as I do in 2 places at once. One world containing books England & all the people with whom I can exchange an idea; the other all that I actually see & hear & speak to. The separation is as complete as between the things in a picture & the things in the room. The puzzle is that both move & act, & [I] must say my say as one of each. The result is that one world at least must think me crazy. I am just now in a sad mess. A drover who has got rich with cattle dealing wanted me to go & teach his daughter. As the man is a widower I astonished this world when I accepted his proposal, & still more because I asked too high a price (£70) a year. Now that I have begun the same people can’t conceive why I don’t go on & marry the man at once which they imagine must have been my original intention. For my part I shall possibly astonish them a little more for I feel a great inclination to make use of his interested civilities to visit his daughter &see the district of Porirua.

If I had a little more money & could afford a horse (she rides) I certainly would. But I can see nothing till I get a horse, which I shall have if I’m lucky in 2 or 3 years.

I have just made acquaintance with Dr & Mrs. Logan. He is a retired navy doctor & has more general knowledge than any one I have talked to here. For instance he had heard of Phillippe Egalite—of a camera obscura; of the resemblance the English language has to the German &c &c. Mrs. Taylor Miss Knox & Mrs. Logan sat in mute admiration while we mentioned these things, being employed in the meantime in making a patchwork quilt. Did you never notice that the women of the middle classes are generally too ignorant to talk to? & that you are thrown entirely on the men for conversation? There is no such feminine inferiority in the lower. The women go hand in hand with the men in the degree of cultivation they are able to reach. I can talk very well to a joiner’s wife, but seldom to a merchant’s.

I must now tell you the fate of your cow. The creature gave so little milk that she is doomed to be fatted & killed. In about 2 months she will fetch perhaps £15 with which I shall buy 3 heifers. Thus you have the chance of getting a calf sometime. My own thrive well & possibly I [shall] have a calf myself. Before this reaches England I shall have 3 or 4.

It’s a pity you don’t live in this world that I might entertain you about the price of meat. Do you know I bought 6 heifers the other day for £23? & now it is turned so cold I expect to hear one half of them are dead. One man bought 20 sheep for £8 & they are all dead but 1. Another bought £150 & has 40 left; and people have begun to drive cattle through a valley into the Wairau plains & thence across the straits of Wellington. &c &c. This is the only legitimate subject of conversation we have the rest is gos[sip] concerning our superiors in station who don’t know us on the road, but it is astonishing how well we know all their private affairs, making allowance always for the distortion in our own organs of vision.

I have now told you everything I can think of except that the cat’s on the table & that I’m going to borrow a new book to read. No less than an account of all the systems of philosophy of modern Europe. I have lately met with a wonder a man who thinks Jane Eyre would have done better [to] marry Mr Rivers! He gives no reasons—such people never do.

Mary Taylor

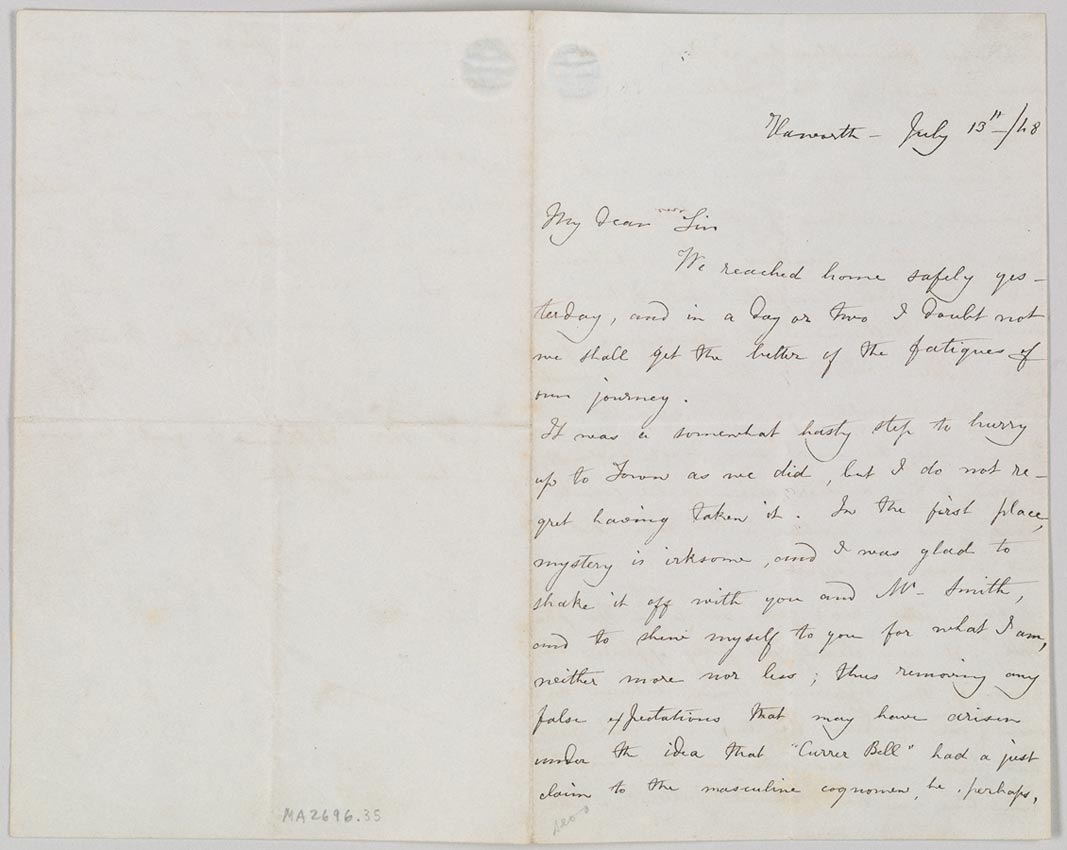

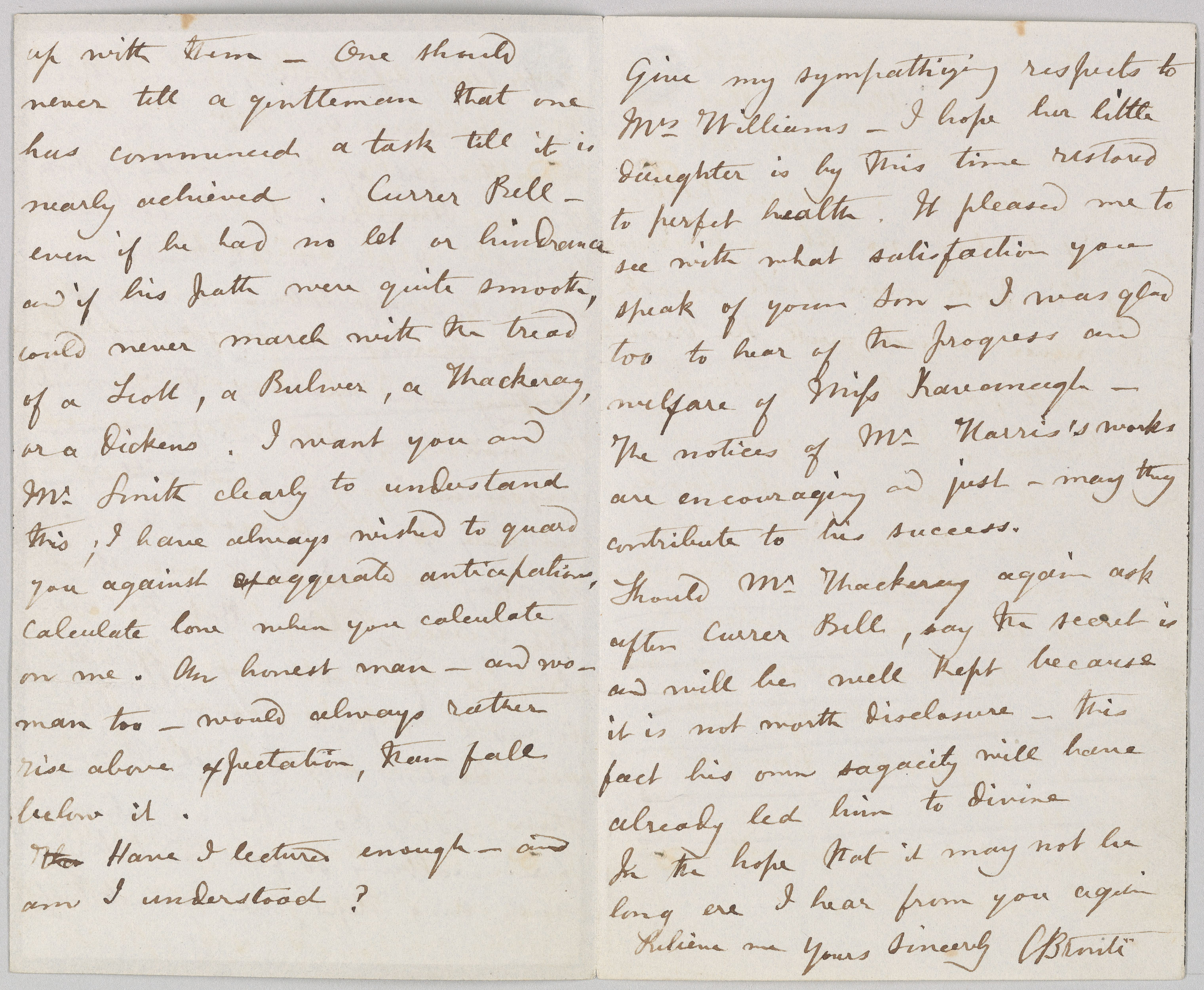

7. Letter to William S. Williams, 13 July 1848, page 1

Letter to William S. Williams of Smith, Elder & Co., dated Haworth, 13 July 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

After Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey were published in quick succession in 1847, readers and critics were full of curiosity about this hitherto unknown literary family. Were there really three Bells? Were they really men? And if they were women, why was their work so bold? Charlotte and Anne Brontë finally took a drastic step. They boarded a train to London and presented themselves at the offices of Smith, Elder & Co., Charlotte’s publisher. Not only did they reveal themselves as women, they made clear, by arriving together, that there was more than one Bell. When they returned to Haworth, Charlotte sent this letter, expressing relief at having revealed herself “for what I am.”

My dear Sir

We reached home safely yesterday, and in a day or two I doubt not we shall get the better of the fatigues of our journey.

It was a somewhat hasty step to hurry up to Town as we did, but I do not regret having taken it. In the first place, mystery is irksome, and I was glad to shake it off with you and Mr. Smith, and to shew myself to you for what I am, neither more nor less; thus removing any false expectations that may have arisen under the idea that “Currer Bell” had a just claim to the masculine cognomen, he, perhaps,

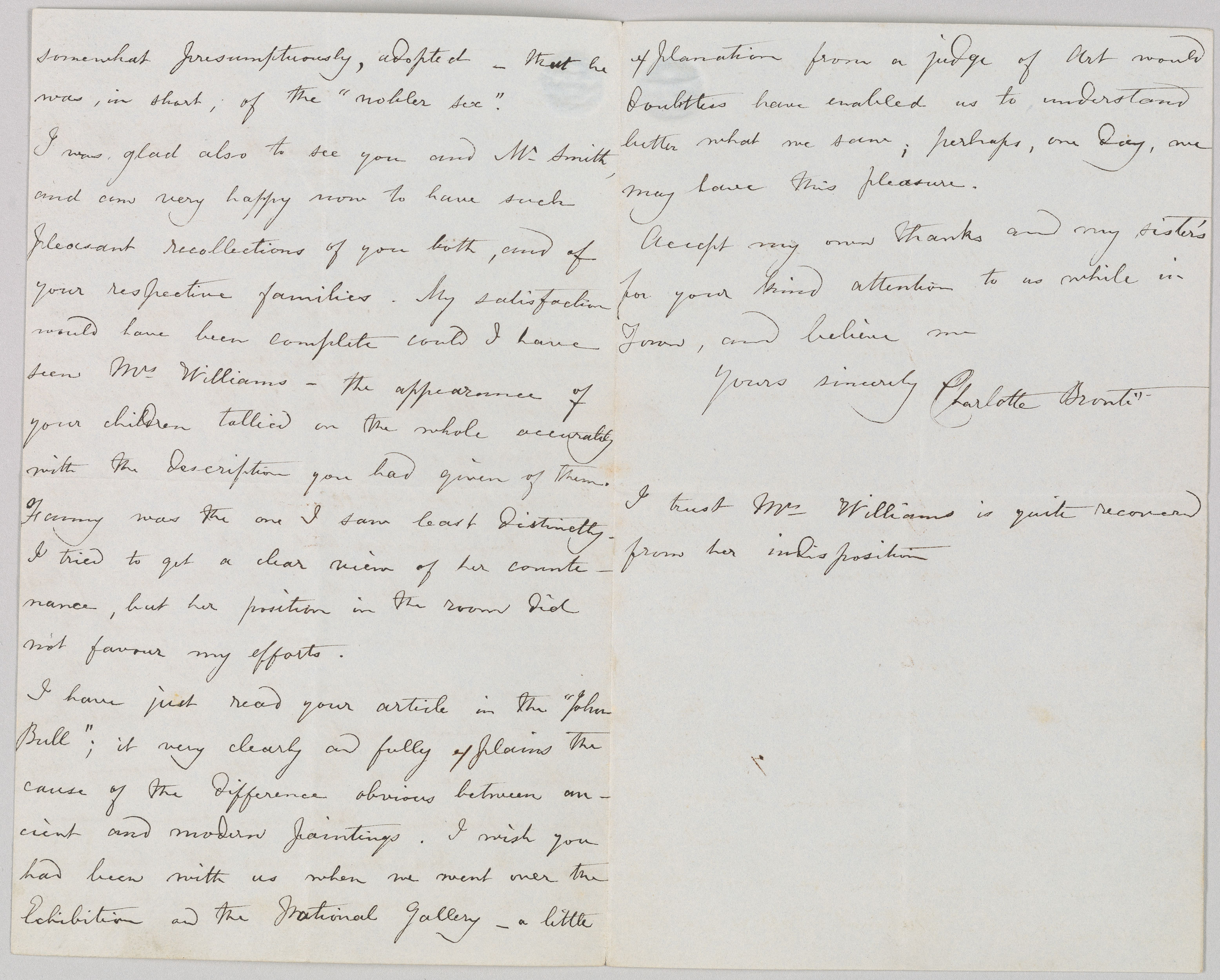

Letter to William S. Williams, 13 July 1848, pages 2–3

Letter to William S. Williams of Smith, Elder & Co., dated Haworth, 13 July 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

After Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey were published in quick succession in 1847, readers and critics were full of curiosity about this hitherto unknown literary family. Were there really three Bells? Were they really men? And if they were women, why was their work so bold? Charlotte and Anne Brontë finally took a drastic step. They boarded a train to London and presented themselves at the offices of Smith, Elder & Co., Charlotte’s publisher. Not only did they reveal themselves as women, they made clear, by arriving together, that there was more than one Bell. When they returned to Haworth, Charlotte sent this letter, expressing relief at having revealed herself “for what I am.”

somewhat presumptuously, adopted – that he was, in short, of the “nobler sex.”

I was glad also to see you and Mr. Smith, and am very happy now to have such pleasant recollections of you both, and of your respective families. My satisfaction would have been complete could I have seen Mrs. Williams – the appearance of your children tallied on the whole accurately with the description you had given of them. Fanny was the one I saw least distinctly – I tried to get a clear view of her countenance, but her position in the room did not favour my efforts.

I have just read your article in the “John Bull”; it very clearly and fully explains the cause of the difference obvious between ancient and modern paintings. I wish you had been with us when we went over the Exhibition and the National Gallery – a little explanation from a judge of Art would doubtless have enabled us to understand better what we saw; perhaps, one day, we may have this pleasure.

Accept my own thanks and my sister’s for your kind attention to us while in Town, and believe me

Yours sincerely

Charlotte Brontë

I trust Mrs. Williams is quite recovered from her indisposition

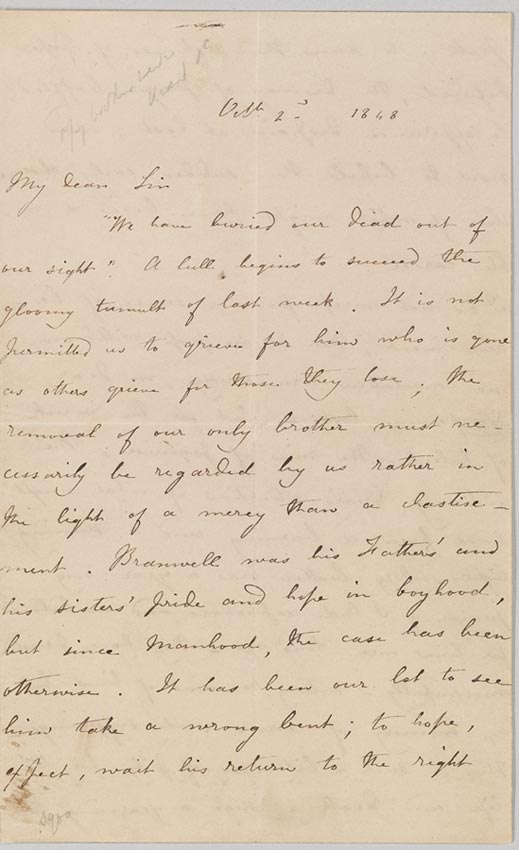

8. Letter to William S. Williams, 2 October 1848, page 1

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 2 October 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few days after her brother, Branwell, died in 1848, Brontë used a sheet of mourning stationery to share the news with William S. Williams of the publishing firm Smith, Elder & Co., who had become a friend. Her grief was compounded by her anger that Branwell had, in her view, squandered his “burning” talent.

My dear Sir

“We have buried our dead out of our sight.” A lull begins to succeed the gloomy tumult of last week. It is not permitted us to grieve for him who is gone as others grieve for those they lose; the removal of our only brother must necessarily be regarded by us rather in the light of a mercy than a chastisement. Branwell was his Father’s and his sisters’ pride and hope in boyhood, but since Manhood, the case has been otherwise. It has been our lot to see him take a wrong bent; to hope, expect, wait his return to the right

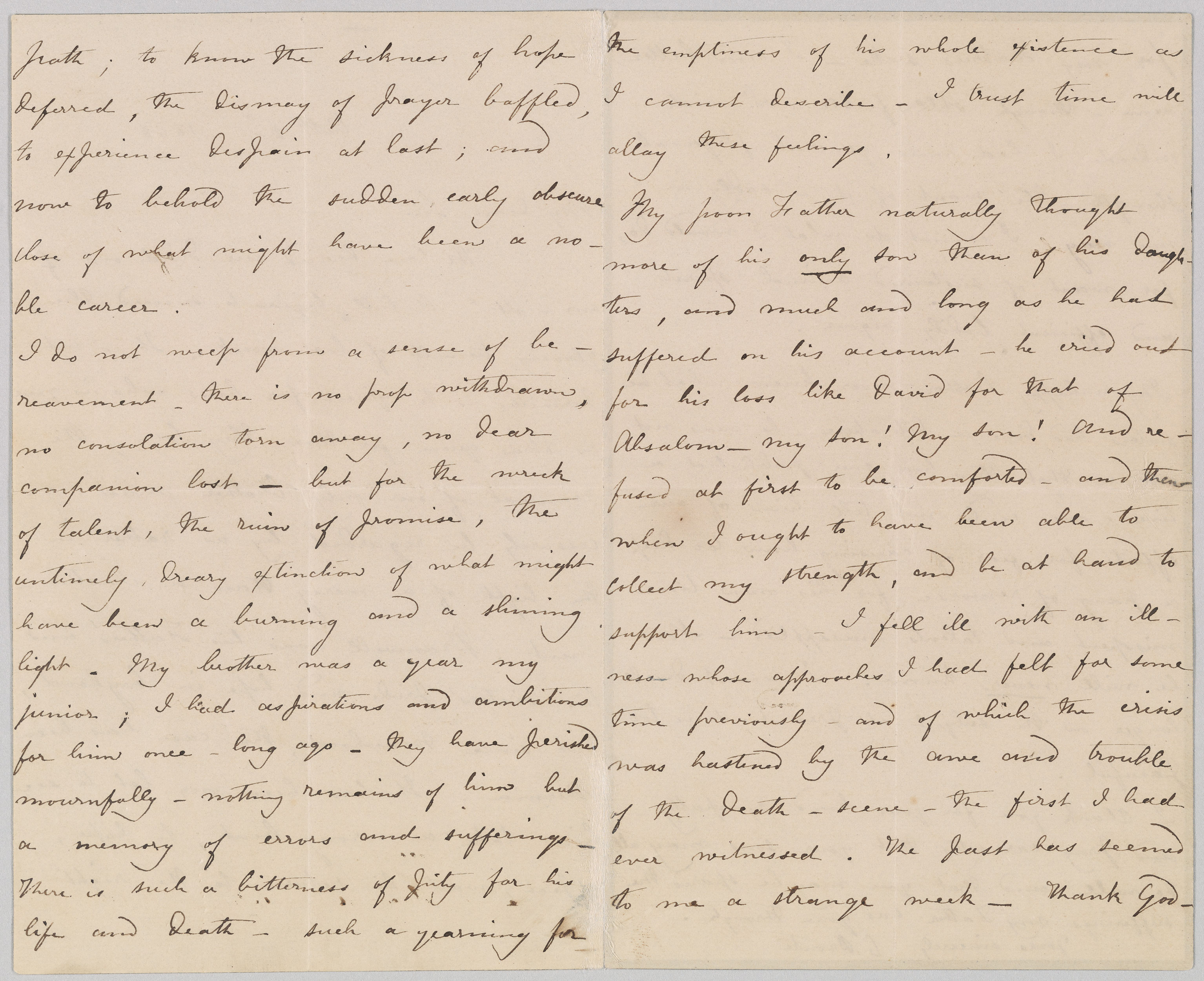

Letter to William S. Williams, 2 October 1848, pages 2–3

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 2 October 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few days after her brother, Branwell, died in 1848, Brontë used a sheet of mourning stationery to share the news with William S. Williams of the publishing firm Smith, Elder & Co., who had become a friend. Her grief was compounded by her anger that Branwell had, in her view, squandered his “burning” talent.

path; to know the sickness of hope deferred, the dismay of prayer baffled, to experience despair at last; and now to behold the sudden early obscure close of what might have been a noble career.

I do not weep from a sense of bereavement – there is no prop withdrawn, no consolation torn away, no dear companion lost – but for the wreck of talent, the ruin of promise, the untimely, dreary extinction of what might have been a burning and a shining light. My brother was a year my junior; I had aspirations and ambitions for him once – long ago – they have perished mournfully nothing remains of him but a memory of errors and sufferings – There is such a bitterness of pity for his life and death – such a yearning for the emptiness of his whole existence as I cannot describe – I trust time will allay these feelings.

My poor Father naturally thought more of his only son than of his daughters, and much and long as he had suffered on his account – he cried out for his loss like David for that of Absalom – My Son! My Son! And refused at first to be comforted – and then – when I ought to have been able to collect my strength, and be at hand to support him – I fell ill with an illness whose approaches I had felt for some time previously – and of which the crisis was hastened by the awe and trouble of the death-scene – the first I had ever witnessed. The past has seemed to me a strange week – Thank God –

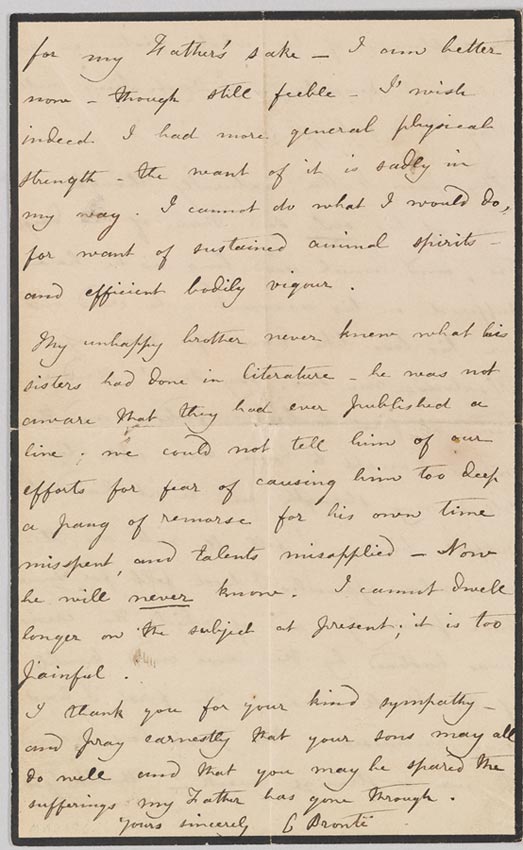

Letter to William S. Williams, 2 October 1848, page 4

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 2 October 1848

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

A few days after her brother, Branwell, died in 1848, Brontë used a sheet of mourning stationery to share the news with William S. Williams of the publishing firm Smith, Elder & Co., who had become a friend. Her grief was compounded by her anger that Branwell had, in her view, squandered his “burning” talent.

for my Father’s sake – I am better now – though still feeble – I wish indeed I had more general physical strength – the want of it is sadly in my way. I cannot do what I would do, for want of sustained animal spirits – and efficient bodily vigour.

My unhappy brother never knew what his sisters had done in literature – he was not aware that they had ever published a line; we could not tell him of our efforts for fear of causing him too deep a pang of remorse for his own time misspent, and talents misapplied – Now he will never know. I cannot dwell longer on the subject at present; it is too painful.

I thank you for your kind sympathy – and pray earnestly that your sons may all do well and that you may be spared the sufferings my Father has gone through.

Yours sincerely

C Brontë

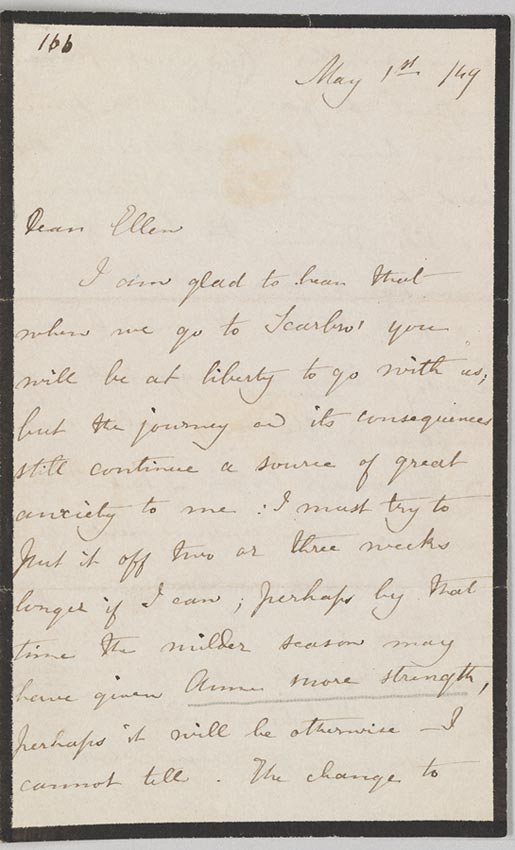

9. Letter to Ellen Nussey, 1 May 1849, page 1

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 1 May 1849

Charlotte Brontë’s brother, Branwell, and sister Emily both died in late 1848. Within months, her last surviving sibling, Anne, was also gravely ill. In this letter to her close friend Ellen, Charlotte reveals her anxiety about their planned trip to the seaside town of Scarborough, where Anne had begged to be taken. Charlotte, Anne, and Ellen did make the trip, and Anne died there, at the age of twenty-nine, a few weeks after Charlotte sent this letter.

I am glad to hear that when we go to Scarbro’ you will be at liberty to go with us; but the journey and its consequences still continue a source of great anxiety to me: I must try to put it off two or three weeks longer if I can; perhaps by that time the milder season may have given Anne more strength, perhaps it will be otherwise – I cannot tell. The change to

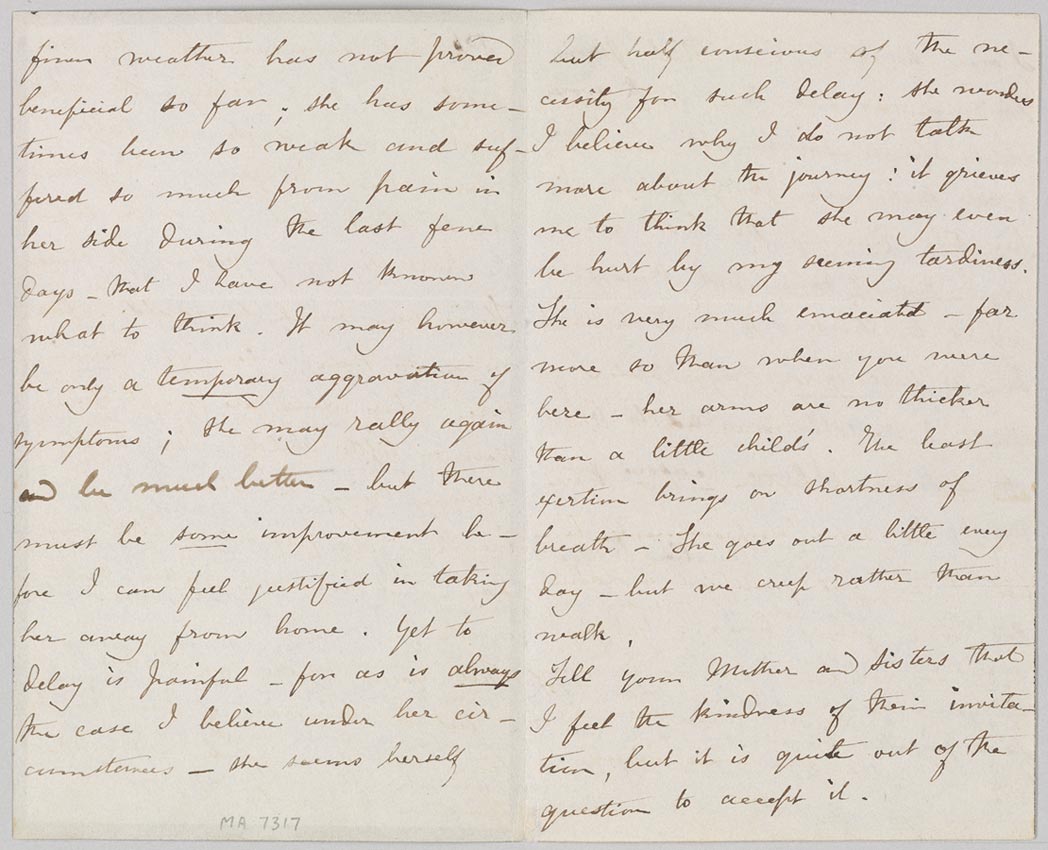

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 1 May 1849, pages 2–3

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 1 May 1849

Charlotte Brontë’s brother, Branwell, and sister Emily both died in late 1848. Within months, her last surviving sibling, Anne, was also gravely ill. In this letter to her close friend Ellen, Charlotte reveals her anxiety about their planned trip to the seaside town of Scarborough, where Anne had begged to be taken. Charlotte, Anne, and Ellen did make the trip, and Anne died there, at the age of twenty-nine, a few weeks after Charlotte sent this letter.

finer weather has not proved beneficial so far; she has sometimes been so weak and suffered so much from pain in her side during the last few days – that I have not known what to think. It may however be only a temporary aggravation of symptoms; she may rally again and be much better – but there must be some improvement before I can feel justified in taking her away from home. Yet to delay is painful – for as is always the case I believe under her circumstances – she seems herself but half conscious of the necessity for such delay: she wonders I believe why I do not talk more about the journey: it grieves me to think that she may even be hurt by my seeming tardiness.

She is very much emaciated – far more so than when you were here – her arms are no thicker than a little child’s. The least exertion brings on shortness of breath – She goes out a little every day – but we creep rather than walk.

Tell your Mother and Sisters that I feel the kindness of their invitation, but it quite out of the question to accept it.

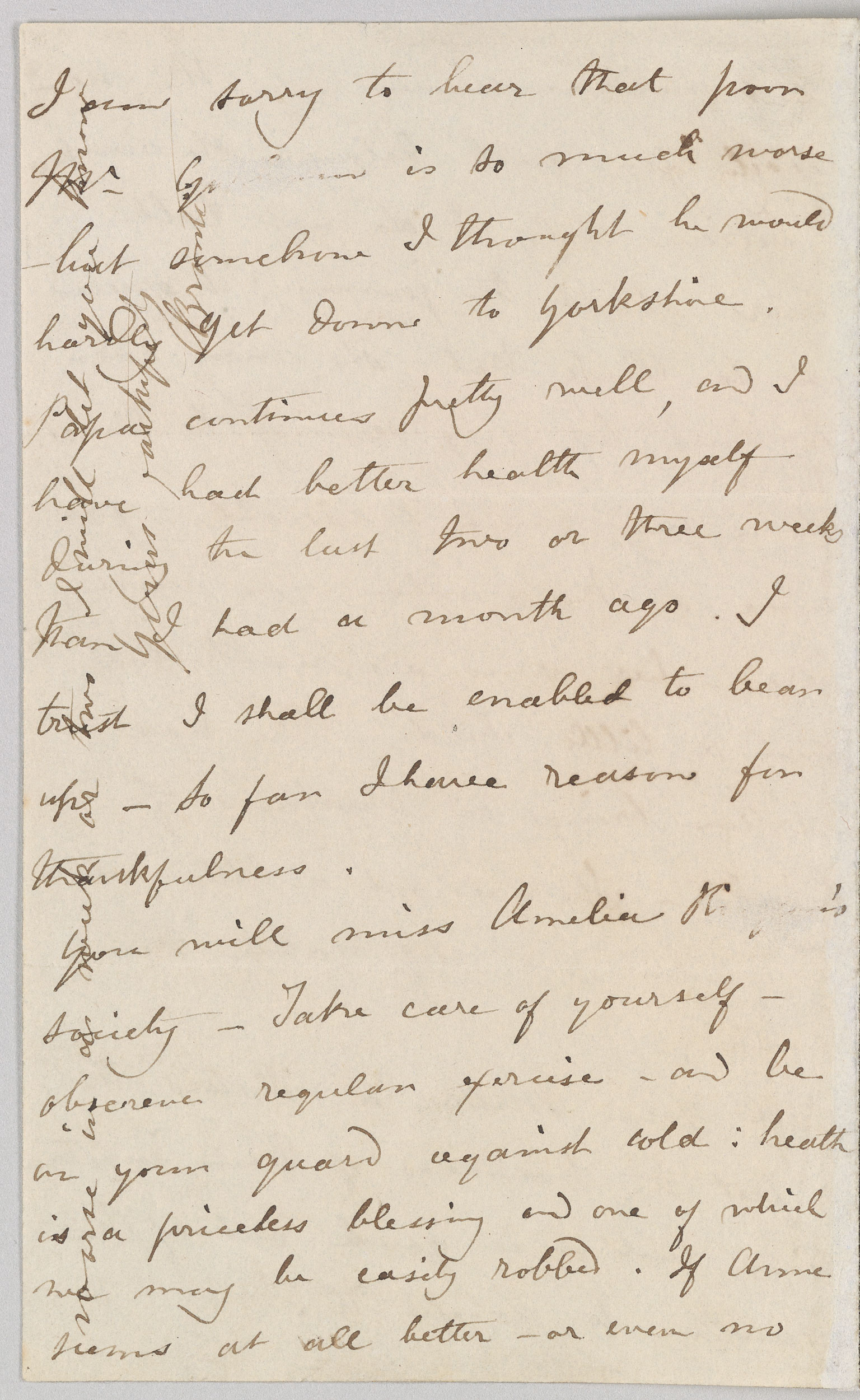

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 1 May 1849, page 4

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 1 May 1849

Charlotte Brontë’s brother, Branwell, and sister Emily both died in late 1848. Within months, her last surviving sibling, Anne, was also gravely ill. In this letter to her close friend Ellen, Charlotte reveals her anxiety about their planned trip to the seaside town of Scarborough, where Anne had begged to be taken. Charlotte, Anne, and Ellen did make the trip, and Anne died there, at the age of twenty-nine, a few weeks after Charlotte sent this letter.

I am sorry to hear that poor Mr. Gorham is so much worse – but somehow I thought he would hardly get down to Yorkshire.

Papa continues pretty well, and I have had better health myself during the last two or three weeks than I had a month ago. I trust I shall be enabled to bear up – So far I have reason for thankfulness.

You will miss Amelia Ringrose’s society – Take care of yourself – observe regular exercise – and be on your guard against cold: hea[l]th is a priceless blessing and one of which we may be easily robbed. If Anne seems at all better – or even no worse in a week or two I will let you know

Yours faithfully

C Brontë

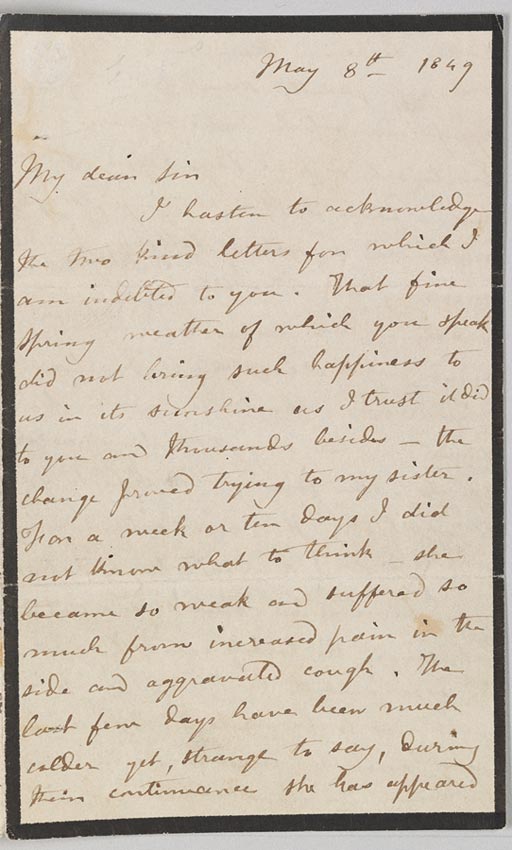

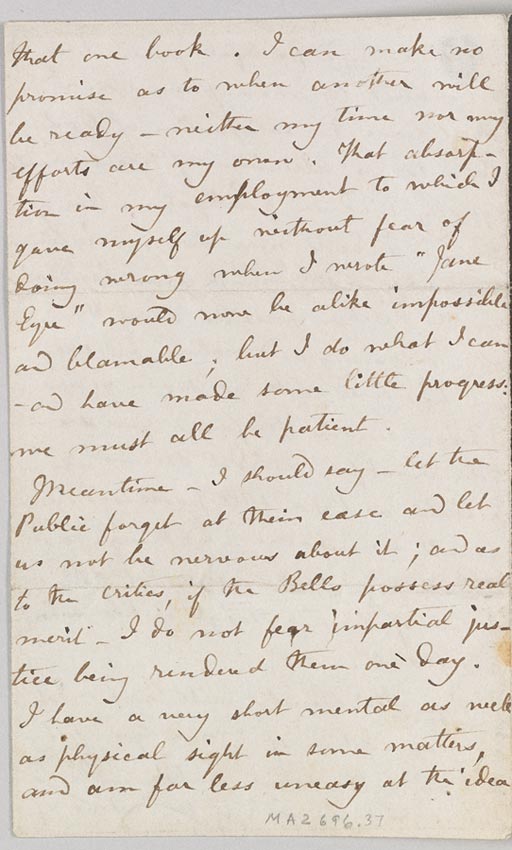

10. Letter to William S. Williams, 8 May 1849, page 1

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 8 May 1849

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë wrote this letter to her friend William S. Williams of the firm Smith, Elder, & Co., which had published Jane Eyre, to send him a wrenching update of her sister Anne’s decline. She wrote on black-edged mourning stationery, having recently lost her sister Emily and brother, Branwell, both of whom had died a few months before.

My dear Sir

I hasten to acknowledge the two kind letters for which I am indebted to you. That fine Spring weather of which you speak did not bring such happiness to us in its sunshine as I trust it did to you and thousands besides – the change proved trying to my sister. For a week or ten days I did not know what to think – she became so weak, and suffered so much from increased pain in the side and aggravated cough. The last few days have been much colder yet, strange to say, during their continuance she has appeared

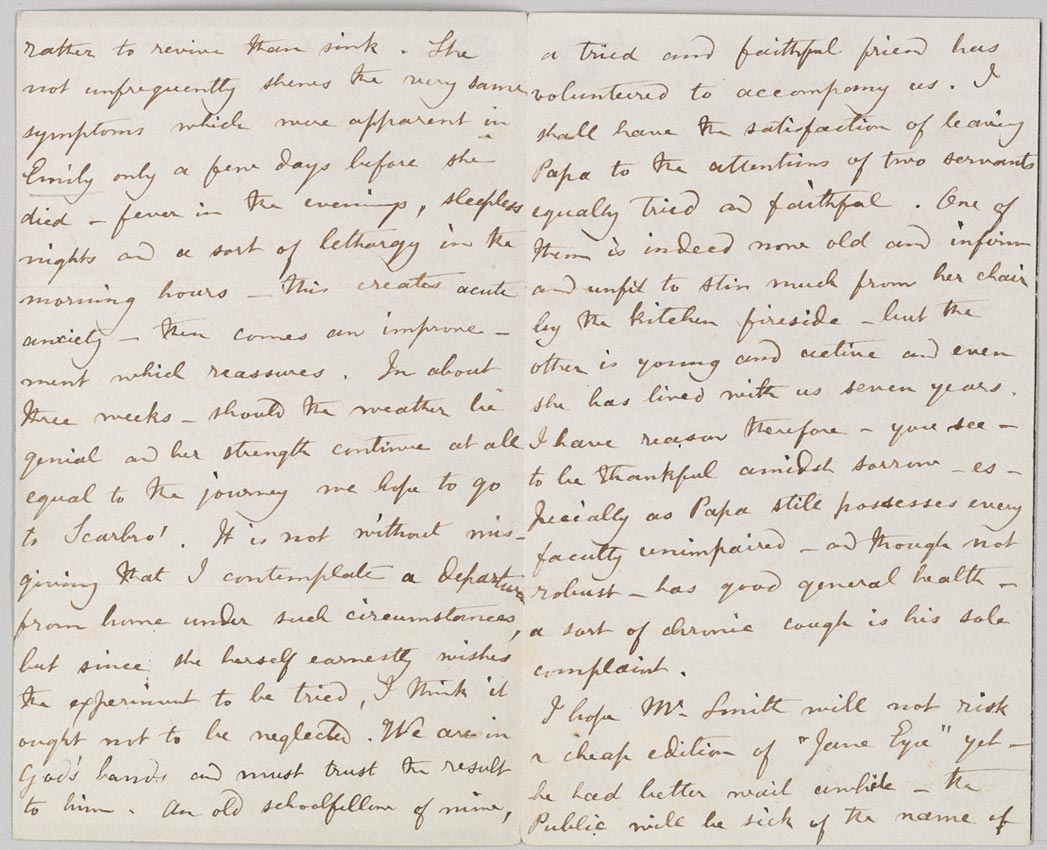

Letter to William S. Williams, 8 May 1849, pages 2–3

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 8 May 1849

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë wrote this letter to her friend William S. Williams of the firm Smith, Elder, & Co., which had published Jane Eyre, to send him a wrenching update of her sister Anne’s decline. She wrote on black-edged mourning stationery, having recently lost her sister Emily and brother, Branwell, both of whom had died a few months before.

rather to revive than sink. She not unfrequently shews the very same symptoms which were apparent in Emily only a few days before she died – fever in the evenings, sleepless nights and a sort of lethargy in the morning hours – this creates acute anxiety – then comes an improvement which reassures. In about three weeks – should the weather be genial and her strength continue at all equal to the journey we hope to go to Scarbro’. It is not without misgiving that I contemplate a departure from home under such circumstances, but since she herself earnestly wishes the experiment to be tried, I think it ought not to be neglected. We are in God’s hands and must trust the result to Him. An old schoolfellow of mine, a tried and faithful friend has volunteered to accompany us. I shall have the satisfaction of leaving Papa to the attentions of two servants equally tried and faithful. One of them is indeed now old and infirm, and unfit to stir much from her chair by the kitchen fireside – but the other is young and active, and even she has lived with us seven years. I have reason therefore – you see – to be thankful amidst sorrow – especially as Papa still possesses every faculty unimpaired – and though not robust – has good general health – a sort of chronic cough is his sole complaint.

I hope Mr. Smith will not risk a cheap edition of “Jane Eyre” yet – he had better wait awhile – the Public will be sick of the name of

Letter to William S. Williams, 8 May 1849, page 4

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 8 May 1849

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë wrote this letter to her friend William S. Williams of the firm Smith, Elder, & Co., which had published Jane Eyre, to send him a wrenching update of her sister Anne’s decline. She wrote on black-edged mourning stationery, having recently lost her sister Emily and brother, Branwell, both of whom had died a few months before.

that one book. I can make no promise as to when another will be ready – neither my time nor my efforts are my own. That absorption in my employment to which I gave myself up without fear of doing wrong when I wrote “Jane Eyre” would now be alike impossible and blamable; but I do what I can – and have made some little progress: we must all be patient.

Meantime – I should say – let the Public forget at their ease and let us not be nervous about it; and as to the critics, if the Bells possess real merit – I do not fear impartial justice being rendered them one day.

I have a very short mental as well as physical sight in some matters, and am far less uneasy at the idea

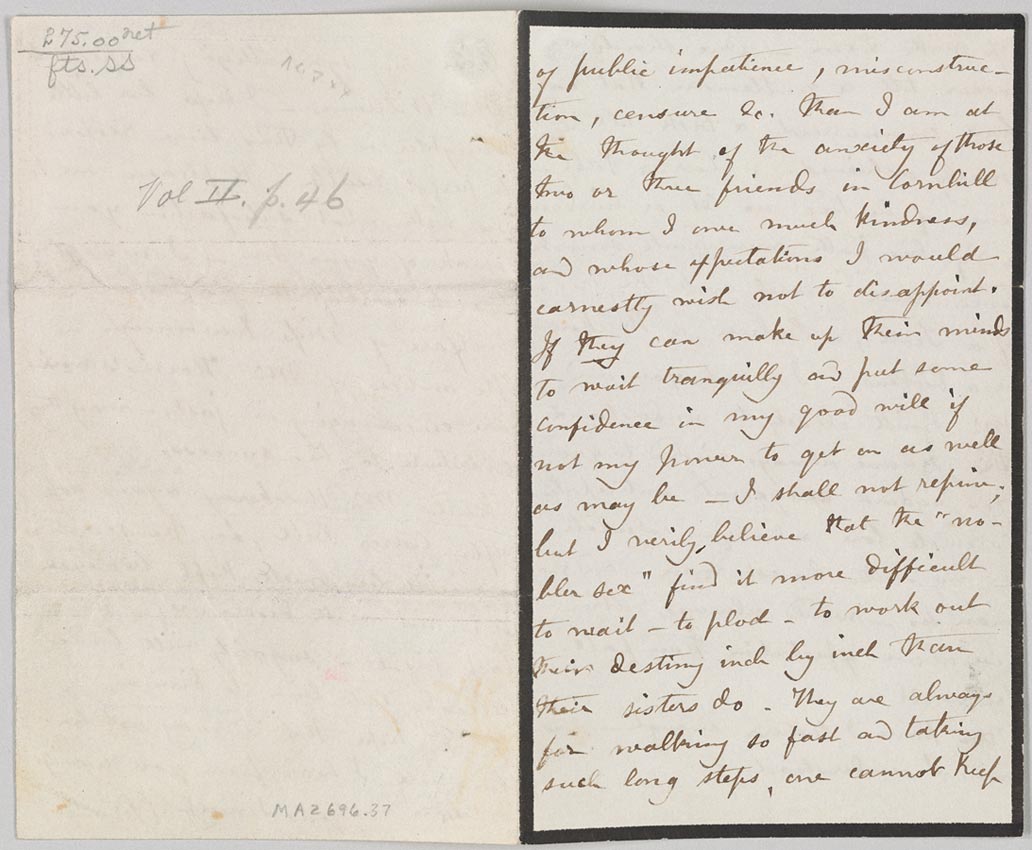

Letter to William S. Williams, 8 May 1849, page 5

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 8 May 1849

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë wrote this letter to her friend William S. Williams of the firm Smith, Elder, & Co., which had published Jane Eyre, to send him a wrenching update of her sister Anne’s decline. She wrote on black-edged mourning stationery, having recently lost her sister Emily and brother, Branwell, both of whom had died a few months before.

of public impatience, misconstruction, censure, &c. than I am at the thought of the anxiety of those two or three friends in Cornhill to whom I owe much kindness, and whose expectations I would earnestly wish not to disappoint. If they can make up their minds to wait tranquilly and put some confidence in my good will if not my power to get on as well as may be – I shall not repine; but I verily believe that the “nobler sex” find it more difficult to wait – to plod – to work out their destiny inch by inch than their sisters do – They are always for walking so fast and taking such long steps, one cannot keep

Letter to William S. Williams, 8 May 1849, pages 6–7

Letter to William S. Williams, dated Haworth, 8 May 1849

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë wrote this letter to her friend William S. Williams of the firm Smith, Elder, & Co., which had published Jane Eyre, to send him a wrenching update of her sister Anne’s decline. She wrote on black-edged mourning stationery, having recently lost her sister Emily and brother, Branwell, both of whom had died a few months before.

up with them – One should never tell a gentleman that one has commenced a task till it is nearly achieved. Currer Bell – even if he had no let or hindrance, and if his path were quite smooth, could never march with the tread of a Scott, a Bulwer, a Thackeray, or a Dickens. I want you and Mr. Smith clearly to understand this; I have always wished to guard you against exaggerated anticipations, calculate low when you calculate on me. An honest man – and woman too – would always rather rise above expectation, than fall below it.

The Have I lectured enough – and am I understood?

Give my sympathizing respects to Mrs. Williams – I hope her little daughter is by this time restored to perfe[c]t health. It pleased me to see with what satisfaction you speak of your Son – I was glad too to hear of the progress and welfare of Miss Kavanagh –

The notices of Mr Harris’s work are encouraging and just – may they contribute to his success.

Should Mr Thackeray again ask after Currer Bell, say the secret is and will be well kept because it is not worth disclosure – this fact his own sagacity will have already led him to divine.

In the hope that it may not be long ere I hear from you again

Believe me

Yours sincerely

C Brontë

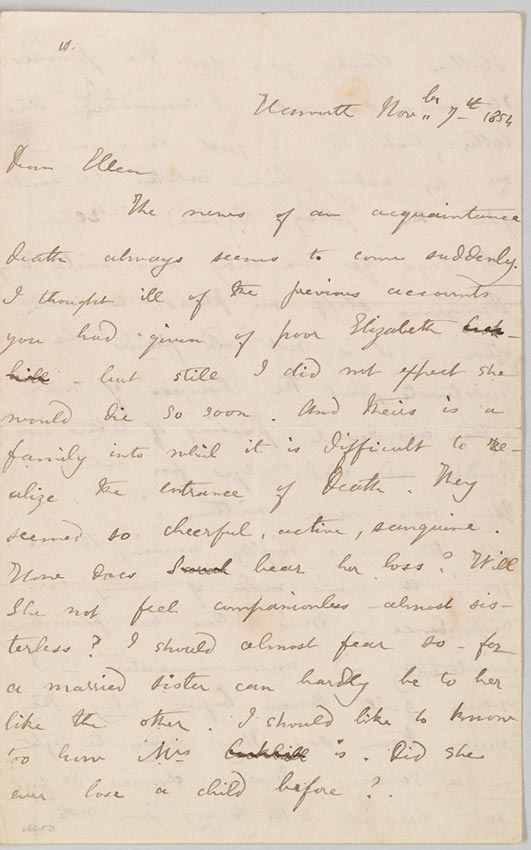

11. Letter to Ellen Nussey, 7 November 1854, page 1

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 7 November 1854

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë’s husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls, was eager to keep his famous wife’s personal letters from prying eyes. He extracted a promise from Ellen Nussey, Brontë’s intimate friend and frequent correspondent, to burn those she received. Brontë died almost five months after writing this letter, which Nussey preserved (along with many others), breaking her disingenuous vow. Brontë’s widower came to understand the public’s longing for personal traces of his late wife, authorizing Elizabeth Gaskell to write the revealing biography she published in 1857.

Dear Ellen

The news of an acquaintance death always seems to come suddenly. I thought ill of the previous accounts you had given of poor Elizabeth Cockhill – but still I did not expect she would die so soon. And theirs is a family into which it is difficult to realize the entrance of Death. They seemed so cheerful, active, sanguine. How does Sarah bear her loss? Will she not feel companionless – almost sisterless? I should almost fear so – for a married Sister can hardly be to her like the other. I should like to know too how Mrs Cockhill is. Did she ever lose a child before?

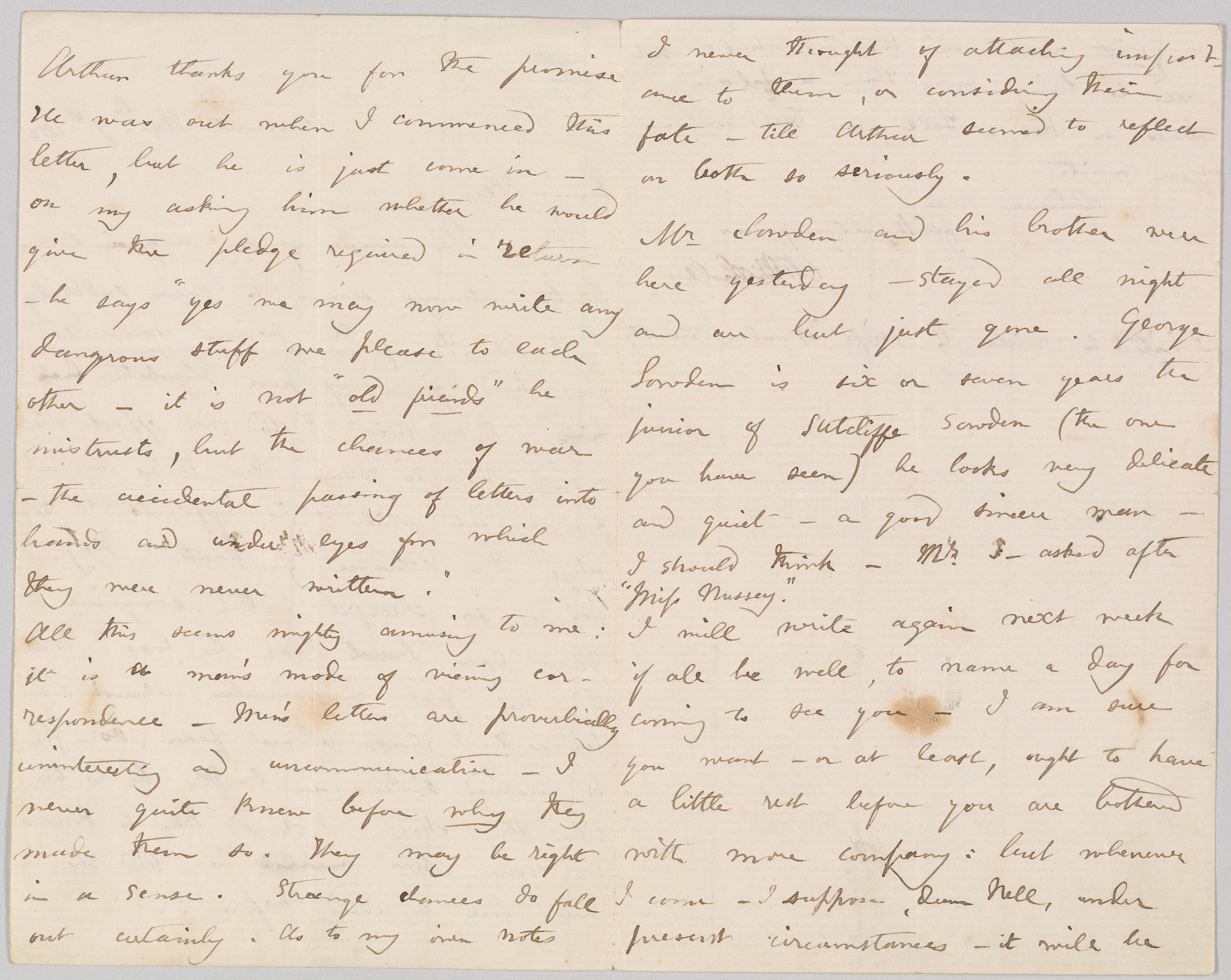

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 7 November 1854, pages 2–3

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 7 November 1854

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë’s husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls, was eager to keep his famous wife’s personal letters from prying eyes. He extracted a promise from Ellen Nussey, Brontë’s intimate friend and frequent correspondent, to burn those she received. Brontë died almost five months after writing this letter, which Nussey preserved (along with many others), breaking her disingenuous vow. Brontë’s widower came to understand the public’s longing for personal traces of his late wife, authorizing Elizabeth Gaskell to write the revealing biography she published in 1857.

Arthur thanks you for the promise. He was out when I commenced this letter, but he is just come in – on my asking him whether he would give the pledge required in return – he says “yes we may now write any dangerous stuff we please to each other – it is not “old friends” he mistrusts, but the chances of war – the accidental passing of letters into hands and under eyes for which they were never written.”

All this seems mighty amusing to me: it is a man’s mode of viewing correspondence – Men’s letters are proverbially uninteresting and uncommunicative – I never quite knew before why they made them so. They may be right in a sense. Strange chances do fall out certainly. As to my own notes I never thought of attaching importance to them, or considering their fate – till Arthur seemed to reflect on both so seriously.

Mr Sowden and his brother were here yesterday – stayed all night and are but just gone. George Sowden is six or seven years the junior of Sutcliffe Sowden (the one you have seen) he looks very delicate and quiet – a good sincere man – I should think – Mr. S – asked after “Miss Nussey.”

I will write again next week if all be well, to name a day for coming to see you – I am sure you want – or at least, ought to have a little rest before you are bothered with more company: but whenever I come – I suppose, dear Nell, under present circumstances – it will be

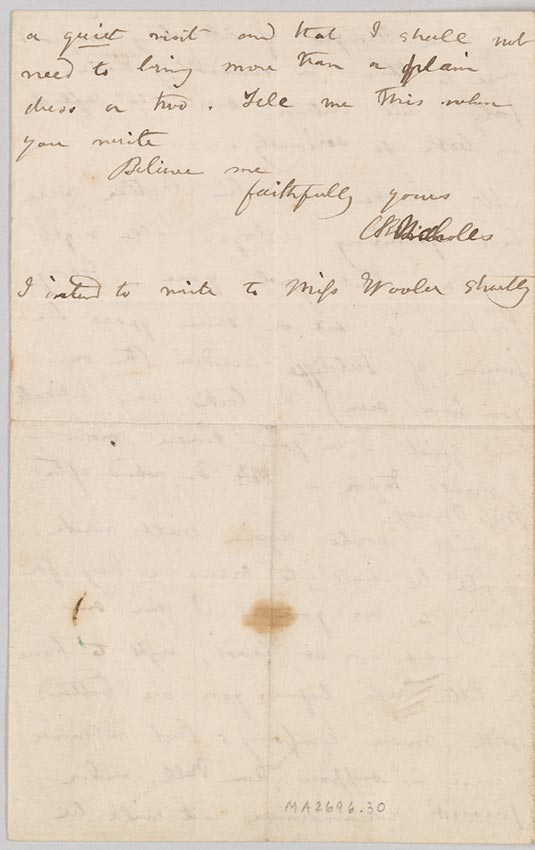

Letter to Ellen Nussey, 7 November 1854, page 4

Letter to Ellen Nussey, dated Haworth, 7 November 1854

Henry H. Bonnell Collection, bequest of Helen Safford Bonnell, 1969

Brontë’s husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls, was eager to keep his famous wife’s personal letters from prying eyes. He extracted a promise from Ellen Nussey, Brontë’s intimate friend and frequent correspondent, to burn those she received. Brontë died almost five months after writing this letter, which Nussey preserved (along with many others), breaking her disingenuous vow. Brontë’s widower came to understand the public’s longing for personal traces of his late wife, authorizing Elizabeth Gaskell to write the revealing biography she published in 1857.

a quiet visit and that I shall not need to bring more than a plain dress or two. Tell me this when you write

Believe me

faithfully yours

C Brontë Nicholls

I intend to write to Miss Wooler shortly