Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Vittore Carpaccio

Sacra Conversazione

Gift of the Thaw Collection, 2006

This drawing is a late compositional study for Carpaccio's panel painting of the Virgin and Child with Four Saints in the Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon. The Virgin and Christ Child with Saint John the Baptist and two female saints are set against a complex landscape background inhabited by three hermit saints. At center left, Augustine speaks to the small child; Jerome stands on the rocky arch; and Anthony Abbot sits just inside a small hut surmounted by a cross.

This is Carpaccio's compositional study for a panel painting of about 1500–1512 (Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon). The complex and somewhat bizarre landscape provides the setting for three hermit saints: Augustine, Jerome, and one generally identified as Anthony Abbot, all of whom are described with Carpaccio's typical anecdotal detail. The drawing is one of the earliest in European art to integrate figures into a finished landscape.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Giulio Campagnola

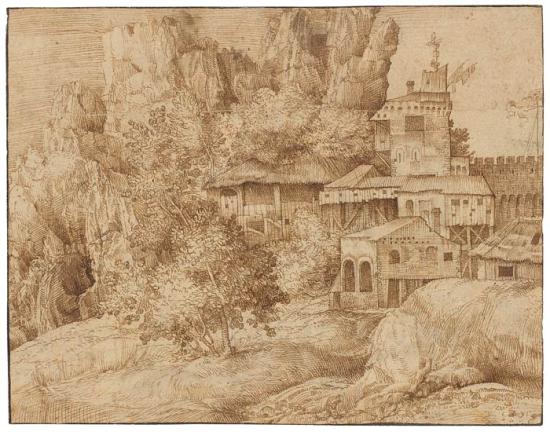

Buildings in a Rocky Landscape

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Engraver and draftsman Giulio Campagnola arrived in Venice in 1507, where he worked in the entourage of Giorgione. Campagnola and his adopted son, Domenico, introduced a new specialty into Venetian art—the pure, narrative-free landscape. Their large, panoramic landscapes created with flowing rhythmic strokes informed succeeding generations, including Pieter Bruegel, Goltzius, and Rubens, and were much sought after by cultivated collectors.

The dense cross-hatching and extreme delicacy with which the artist rendered the picturesque cluster of buildings suggest the influence of both Albrecht Dürer and Giorgione.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Titian

Landscape with St. Theodore Overcoming the Dragon

Inscribed on old mount at center, beneath the drawing, in pen and brown ink, Titiano da Cadore.

Gift of János Scholz, 1977

Arguably the greatest of all Venetian painters, Titian was held in high esteem during his lifetime. His paintings and drawings were as novel in subject matter and composition as they were bold in technique. St. Theodore Overcoming the Dragon is one of the rare landscape drawings attributed to the artist.

Theodore, one of the patron saints of Venice, did not slay the dragon but instead made it roll over in submission. The figure seated under the tree in the background may be the mother who, according to legend, brought her ailing child to be bathed in a miraculous well guarded by the dragon.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Girolamo Romanino

Pastoral Concert with Two Women, a Faun and a Soldier

Gift of Janos Scholz, 1973

To complete his education and attracted by the innovations of Giorgione, Romanino went to Venice, where Albrecht Dürer's Feast of the Rose Garlands and paintings by Giorgione and Titian proved to be a lasting influence on his work.

Following a tradition founded by Titian and Giorgione, the theme of music intermingled with love in a pastoral landscape became popular in northern Italy in the early sixteenth century. This is one of three drawings by Romanino of musical groups with a faun, which are usually associated with frescoes the artist painted in Trent around 1531–32.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.

Paris Bordone

Standing Man Playing a Viola da Gamba (Violoncello)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

The present figure is inspired by a similar portrayal of a musician in a pen-and-ink drawing of a pastoral concert by Titian, to whom Bordone was briefly apprenticed.

Whereas Titian's figure is using the bow to point in the general direction of the area circumscribed by the legs of his seated female companion, Bordone's more autonomous figure is playing the instrument. The composition anticipates the poetic depictions of mythological subjects that became popular in the mid-sixteenth century.

Landscape and Pastoral

Today Venice evokes images of a picturesque city rising from the sea. Yet sixteenth-century Venetian artists rarely depicted the lagoon or its atmospheric effects. Instead they documented alpine vistas or created fantastical scenes. Landscape was such an important element of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting and drawing that it often dominated even works with mythological or religious subjects. This trend was very much in keeping with the strong interest in the natural world that emerged during the Renaissance, when many artists began to rely on direct observation rather than inherited models. Inspired by the works of the ancient poet Virgil, Venetian humanists extolled the simplicity of pastoral life, and writers, composers, and artists alike embraced Arcadian themes of love, poetry, and music.