Ingres at the Morgan Letters

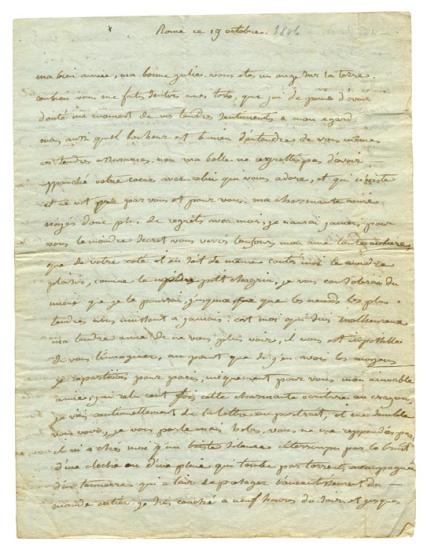

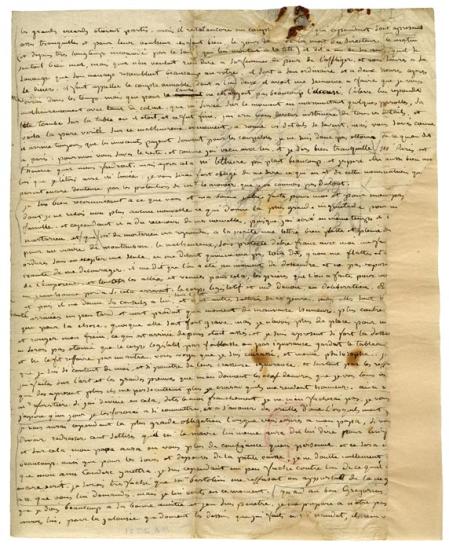

Letter to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, page 1

Letter from Ingres to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, 19 October 1806, page 1

Gift of the Fellows, 1968

In this long, melancholy note to his fiancée, Ingres laments his intense homesickness during his first days in Rome. He had arrived the previous week to begin his residency at the Villa Medici, after a long journey via Turin, Milan, Lodi, Piacenza, Parma, Reggio, Modena, Bologna, and finally Florence. He writes, "I lie down from nine at night until six in the morning, I do not sleep, I roll around in my bed, I cry, I think continuously of you...." Nine months later, Ingres would break his engagement, citing his unwillingness to return to Paris after the negative reviews his paintings had received at the Salon.

Rome, 19 October 1806

My beloved, my good Julie, you are an angel on earth. How you make me aware of my failings! How sorry I am to have doubted for a moment your tender feelings toward me, but also what happiness is mine to hear your tender assurances. No, my dear, do not regret having poured out your heart with the one who loves you and who exists and lives only through you and for you. My charming friend, do not express regrets toward me. I will never keep any secret from you, you'll always see my whole soul. May it be the same on your part. Tell me the least pleasure as well as the smallest sorrow. I will comfort you the best I can, until the tenderest vows unite us forever. It is I who am unhappy my dear friend, not to see you any more; you can't possibly conceive of it, to the point that if I could afford it, I would return to Paris, only for you my kind friend. I have read a hundred times this lovely writing in pencil; I shift continually from the letter to the portrait. I seem to see you, I speak to you, but, alas, you do not answer; at my home there is only a sad silence interrupted by the sound of a bell or rain falling in torrents, accompanied by a thunder that seems to foreshadow the destruction of the entire world. I go to bed at nine o'clock at night and until

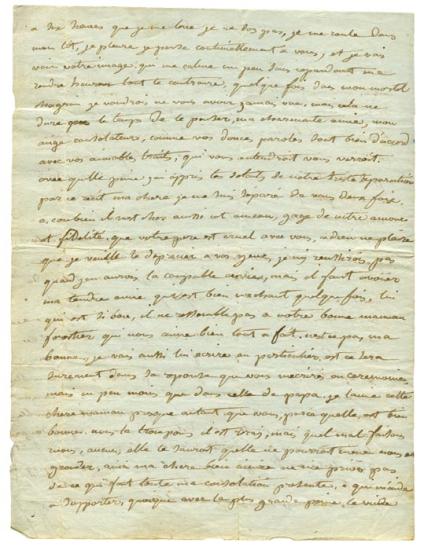

Letter to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, page 2

Letter from Ingres to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, 19 October 1806, page 2

Gift of the Fellows, 1968

In this long, melancholy note to his fiancée, Ingres laments his intense homesickness during his first days in Rome. He had arrived the previous week to begin his residency at the Villa Medici, after a long journey via Turin, Milan, Lodi, Piacenza, Parma, Reggio, Modena, Bologna, and finally Florence. He writes, "I lie down from nine at night until six in the morning, I do not sleep, I roll around in my bed, I cry, I think continuously of you...." Nine months later, Ingres would break his engagement, citing his unwillingness to return to Paris after the negative reviews his paintings had received at the Salon.

six o'clock when I get up, I do not sleep, I roll over in my bed, I cry, I think of you constantly, and I go look at your portrait, which calms me a little, but without making me happy, quite the opposite. Sometimes, in my fatal grief, I wish never to have seen you, but this lasts only the time to think it. My charming friend, my consoling angel, how your sweet words are in agreement with your kind qualities: he who hears you would see you. With what sorrow I learned the details of our sad separation. Through this account, dearest, I left you twice. Ah! how dear to me also is this ring, token of our love and loyalty! How cruel to you is your father! God forbid that I want to belittle him in your eyes, I should not succeed, even though I should have the guilty wish, but I must admit, my dear friend, that he is sometimes very unkind, he who is so good. He is not like our good mother Forestier, who loves us completely, doesn't she, my dear? I will also write to her separately and it will certainly be in her reply that you will write to me, formally, but a little less so than in your father's. I like her, this dear mother, almost as much as you, because she is so good. We mislead her, it is true, but what harm are we doing? None. Were she to know it, she could not even scold us, and so, my darling, do not deprive me of all that gives me comfort now and helps me to bear, though with great difficulty, the awful void

Letter to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, page 3

Letter from Ingres to Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, 19 October 1806, page 3

Gift of the Fellows, 1968

In this long, melancholy note to his fiancée, Ingres laments his intense homesickness during his first days in Rome. He had arrived the previous week to begin his residency at the Villa Medici, after a long journey via Turin, Milan, Lodi, Piacenza, Parma, Reggio, Modena, Bologna, and finally Florence. He writes, "I lie down from nine at night until six in the morning, I do not sleep, I roll around in my bed, I cry, I think continuously of you...." Nine months later, Ingres would break his engagement, citing his unwillingness to return to Paris after the negative reviews his paintings had received at the Salon.

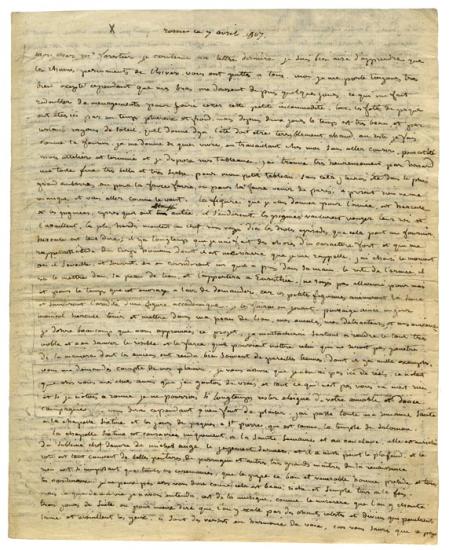

Letter to Charles-Pierre-Michel Forestier, page 1

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Letter from Ingres to Charles-Pierre-Michel Forestier, 7 April 1807, page 1, MA 2701.

Purchased on the Fellows Capital Fund, 1969

Sent to his prospective father-in-law six months after arriving in Rome, this letter indicates that the artist's spirits had improved. Ingres was decidedly entranced by the many masterpieces on public view, such as Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel and "the beautiful paintings of Perugino." He also includes news about recent developments at the French Academy in Rome, notably the sudden death of the director, Joseph Benoît Suveée (1743–1802). Ingres writes of the latter's replacement, Guillaume Lethière, of whom he would later create a masterful portrait: "I really like M. Lethière, and I hope that I will get along with him as well as I did with M. Suvée."

Rome, 7 April 1807, to Monsieur Forestier

My dear Mr. Forestier, I continue my last letter. I am glad to hear that the enduring head colds of winter have left all of you; I am very well, except that my arms have been twitching for several days, which makes me be twice as cautious in order to stop this little inconvenience. All the Easter celebrations have been held in rainy and cold weather, but for the last two days the weather is beautiful, and judging by some rays of the sun, the summer will be terribly hot. Anyway, I am like the ant, I earn my living by working at home without running about. My studio is finished for this summer and I am laying out my paintings. I happily found by chance a fine canvas, very beautiful and very dry, for my little painting, without which I would have been greatly troubled whether to have it made or to have it sent from Paris. Now, nothing is missing and I will move ahead like the wind. The subject that I will present this year is Hercules and the Pygmies. After he had strangled Antaeus, he fell asleep. The Pygmies wanted to avenge their king and attack him. The boldest climb the head. You can imagine the amusing episodes that this can provide me. Hercules, one need say no more. It's been a long time since I have done things of a strong character and that remind me of the study of the human body, which it is necessary that I remember. I chose the moment when he wakes up and smiles, looking at a Pygmy that he holds in his hand. He will put the rest of the army in the lion's skin and bring it to Eurystheus. Do not be alarmed for me and for the time that this work seems to require, because these small figures will animate the scene and temper the aridity of an academic study. I'll paint them playfully. May I one day, a new Hercules, hold and put in my lion skin my rivals, my critics and the envious. I hope very much that you approve of this project, I will commit myself especially to making the work feel noble and to set aside the ludicrous and the farcical elements that might be put in by someone not imbued in how ancient artists treated such scenes, of which there are a thousand examples. You ask for an account of my pleasures, I assure you I have no real ones here. It was only at your home, my dear friends, that I tasted real ones, and everything that is not you is nothing to me and were I not in Rome, I could not stay away so long from your gracious and kind company. I will tell you however in regard to pleasures that I have spent Holy Week in the Sistine Chapel and the Easter holidays in St. Peter, which is like the temple of Solomon. The Sistine Chapel is dedicated solely to the Holy Week and to the conclave. It is enriched by the sublime masterpiece of Michelangelo, The Last Judgment, and he also painted the ceiling, and the rest is covered with beautiful paintings by Perugino and other great masters of the Renaissance. Nothing is more impressive than all these ceremonies, than the Pope, this good and venerable man presiding, and all the cardinals. I cannot tell you enough how it is beautiful, rich and simple all at once, but what I had never heard in my life was music like the Miserere, which is sung on three consecutive days, or, rather, that is exhaled in celestial and divine songs that penetrate the soul and moisten the eyes. These are verses sung in a harmony of voices, for bear in mind that the Pope

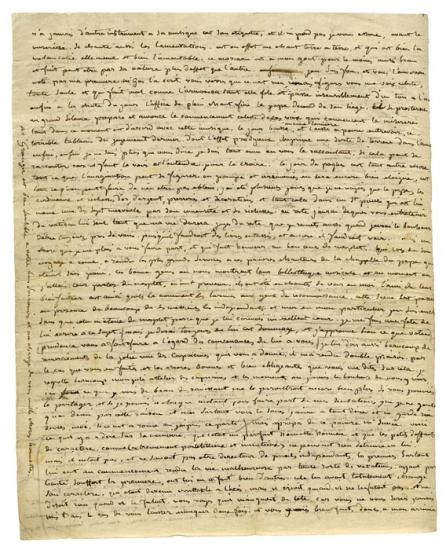

Letter to Charles-Pierre-Michel Forestier, page 2

Letter from Ingres to Charles-Pierre-Michel Forestier, 7 April 1807, page 2

Purchased on the Fellows Capital Fund, 1969

Sent to his prospective father-in-law six months after arriving in Rome, this letter indicates that the artist's spirits had improved. Ingres was decidedly entranced by the many masterpieces on public view, such as Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel and "the beautiful paintings of Perugino." He also includes news about recent developments at the French Academy in Rome, notably the sudden death of the director, Joseph Benoît Suveée (1743–1802). Ingres writes of the latter's replacement, Guillaume Lethière, of whom he would later create a masterful portrait: "I really like M. Lethière, and I hope that I will get along with him as well as I did with M. Suvée."

never has other instruments to his music. It's his earmark and he does not lose thereby, I assure you. Before the Miserere the Lamentations are also sung; it is in fact an earthbound song that is the epitome of melancholy and lament. This piece is, to my taste, at least as good and is perhaps by nature more effective than the other; I'm crazy about it and will send it to you annotated by my first. Mr. Gasse wrote it. You will see that it is nothing much, but just imagine a heavenly voice, all alone and that hurts like the harmonica, as it flows and passes imperceptibly from one tone to another. Finally, at nightfall, the plainsong service ended, the Pope descends from his seat, he prostrates himself, a great silence prepares and announces the heavenly beginning of these voices that begin the Miserere. Everything in this moment is in accordance with this music: no lights, daylight fades and just allows a glimpse of that terrible scene of The Last Judgment, whose prodigious effect imprints a sort of terror in the soul. Finally, finally I do not know what else to say; I am deeply moved while telling you, if telling is possible, because you have to see and hear it to believe it. Easter Sunday, it is an entirely different thing. All that the imagination can dream up of pomp and ceremony will still be far from reality, it's all one can do not to be dazzled. For several days I only saw the Pope, the cardinals, the wealth of gold, silver, jewels and decorations and all that in a Saint Peter, that is itself one of the seven wonders by its vastness and its riches. In fact, I will be able to tell you about the Vatican, itself alone, as long as I live. You'll be able to hear the rest, which I also leave out, when I have the happiness to always be near you, since it would take piles of books and more to fill you in. But one thing that I am pleased to let you know about and that honors the good heart of Mesplet: during his trip to Rome he did great kindness to these poor singers of the Pope's Chapel, who were in the greatest need. These good people were showing us their music library, and when I was about to tell them about Mesplet, they forestalled me. They were delighted to see me as the friend of their benefactor, for so they call him with tears of gratitude in their eyes. This scene took place in the presence of many of these independent gentlemen and I, in my own mind, am delighted without it surprising me of Mesplet, because I know his great heart. I look forward to writing him about it, but I always say about him, "It's too bad," and I approve what your prudence made you do in regard to his breach of good manners. I also owe him a lot of thanks for the lovely view of the Capucines that he gave you, he made me doubly pleased because of the value you set on it and the good and considerate things you tell me about it. I miss my beautiful studio at the Capucines and the times when I had the happiness to see you there; here, all I see that is beautiful, delightful, would seem to me much more so if you could share it and if I could at every moment share my feelings with you, which I enjoy only halfway for this reason, and I especially, as you know, like to say everything and keep nothing to myself, except that in Rome I have decided to do just that. But in regard to this poor Mr. Suvée, here is what there is to say in his memory: that he was a perfectly decent gentleman and his small character failings (like great touchiness and meticulousness) cannot be the ruin of him. But he was not, and should not have been Director of such independent [students]. The first ones especially, made life miserable for him in the beginning through all kinds of provocations. Having, through his goodness, suffered the first, he was made to suffer many others. It totally changed his character, which became extremely irritable. But he shouted when he should not have and said nothing when he should have. You can see that he lacked judgment, for you would never have put yourself in the position of being affronted twice, and you would have done well. So, when I arrived,

Letter to Charles-Pierre-Michel Forestier, page 3

Letter from Ingres to Charles-Pierre-Michel Forestier, 7 April 1807, page 3

Purchased on the Fellows Capital Fund, 1969

Sent to his prospective father-in-law six months after arriving in Rome, this letter indicates that the artist's spirits had improved. Ingres was decidedly entranced by the many masterpieces on public view, such as Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel and "the beautiful paintings of Perugino." He also includes news about recent developments at the French Academy in Rome, notably the sudden death of the director, Joseph Benoît Suveée (1743–1802). Ingres writes of the latter's replacement, Guillaume Lethière, of whom he would later create a masterful portrait: "I really like M. Lethière, and I hope that I will get along with him as well as I did with M. Suvée."

the loud screamers were gone, but there were still a couple who, however, are now fairly quiet, and for their own good, they do well. So the day of the death of the Director, in the morning (and having for a very long time been bothered by blood rushing to his head) he told a friend that he felt very bad, but that he did not want to say anything to his wife so as not to distress her, and you will know, to his credit, that his marriage was very similar to yours; he went out as usual and, at two o'clock after lunch, he called the amiable couple. He had to reprimand one of them, which I will tell you about in due time, but considering the cause, did not inculpate the accused very much. Unfortunately, the student replied so quietly that Mr. Suvée, at that moment, muttering a few words, let his head fall on the table at which he sat and it was over. I thought I should give you all these details, and that's the straight truth about this unfortunate event. In Rome, people know these details, but you know how the innocent always pay for the guilty, I am thus not surprised at what is said in Paris. As for me, you know the rest, and how I have lived with him, and I sleep in peace. Mr. Pâris would be the man we need, but as second best I like Mr. Lethière very much and hope to get along with him as well as I did with Mr. Suvée. I will be much obliged to you for keeping me informed about this appointment, which still seems dubious acording to the claims by Mr. Lemonnier, whom I do not know at all. I am very grateful for what you and my dear Julie do for me and my dad, from whom I no longer receive any news, which gives me the greatest concern for my family, and yet he has to have heard from me as I wrote at the same time to Mr. de Mortarieu and Mr. de Mortarieu answered, in truth, with a very tedious letter full of for a mayor of Montauban. Under the guise of being frank with me the wretched man let me [hear] garbage, not sparing me any, telling me that I have not been told everything, that they flatter me, [for] fear of discouraging me, he said that they were about to take down and not to exhibit [the portrait] of the Emperor and all the comings and goings concerning this, the appeals that have been made in my favor [saying that I would be] a lost young man if that happened. The Legislature and Mr. Denon in deliberation and then he gives me his advice, his, about art and much other such drivel, but they are arrived a little late and have only produced a moment of bad humor, mostly against than for the thing itself, although it is very serious, but I had no more room for...

and fret, since what happened was enough, and I am now well up on this. [I]… would not be surprised that the Legislature, through weakness or through ignorance, should keep the painting... and did not have it redone by another. You see I'm prepared and even philosophical, I that I am so pleased with myself, and so convinced of their filthy ignorance, and especially by my thoughts [that] about art and the great evidence that the masterpieces that I see every [day] give me that from now on, the more they persecute me, the more I believe they honor me. And [therefore]... Mr. Forestier, if I guessed it, tell me frankly, I will not get angry, I [assure you]... I hope that one day I will force them to recognize me and confess to having been asses when they [insulted] me. But I'll bear you the highest obligation, when you write to my dad, if you [feel] you have to correct the one hundred stupidities that the Mayor himself must have told him... and concerning that, my dad will have more confidence in you than in anyone else, and it will be... a lot, as well as the needs and petty cash expenses. I have no doubt [of the willingness] that my friend Couderc will place on it. However, I am a little angry at him for [not having] yet written to me. I would be very angry if Mr. Bortolini should refuse or neg[lect] your request, but I write to him at this moment. As for the good Gregorius, [I know] I owe a lot to his friendship and I appreciate it, I am preparing not to be... ungrateful towards him. As for the jealousy that the drawings I made inspire in Mr. Naudet, they...

[In brown ink on page 2] Mr. Granger appreciates your kind thoughts and asks me to tell you a thousand good things.

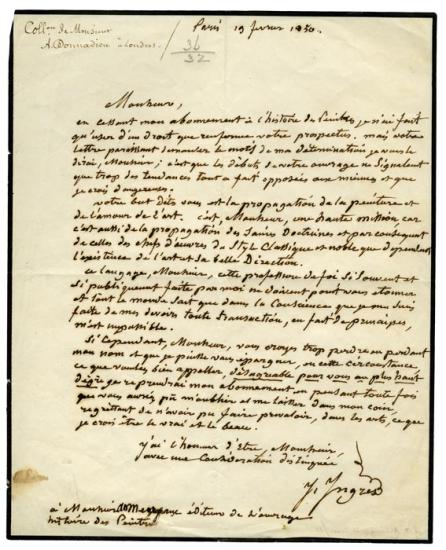

Letter to Jean-Germain-Désiré Amengaud

Letter from Ingres to Jean-Germain-Désiré Amengaud, 19 February 1850

Purchased on the Fellows Fund, 1979

Charles Blanc's monumental Histoire des peintres, a comprehensive and illustrated review of the history of European painting from the Renaissance onward, was first published in 1861, though chapters on individual artists were printed as installments and were available by subscription as early as August 1849. In this indignant letter to the editor of the series, Jean-Germain-Désiré Armengaud (1797–1869), Ingres explains why he had cancelled his subscription. The artist refused to endorse a publication that propagated "trends [in painting] that are entirely opposed to mine and that I believe to be dangerous.".

Paris, 19 February 1850

Sir,

In discontinuing my subscription to the History of Painters, I have only made use of a right included in your prospectus. But your letter appears to ask the reason for my decision, I will tell you, sir; it is that the beginning of your work suggests too many tendencies that are quite opposite to mine and that I believe dangerous. Your goal, you say, is the propagation of painting and of the love of art. That, sir, is an important mission, because it is also the propagation of sound doctrines and therefore of those of the masterpieces of the Classical and noble style on which depend the existence of art and its beautiful direction. This language, sir, this profession of faith so often and so publicly made by me should not surprise you and everyone knows that any compromise in my conception of my duty, as a matter of principle, is impossible. If, however, Sir, you think you lose too much by losing my name and that I can spare you, on this occasion, what you kindly describe as unpleasant for you in the highest degree, I will renew my subscription, thinking all the time, that you could have forgotten me and let me be in my corner, regretful not to have been able to gain acceptance, in the arts, for what I believe to be truth and beauty. I am, Sir, yours very truly J. Ingres to Mr. Armengaux [sic] editor of the work "History of Painters"