See all diaries

A Dark and Stormy Night: Charlotte Brontë

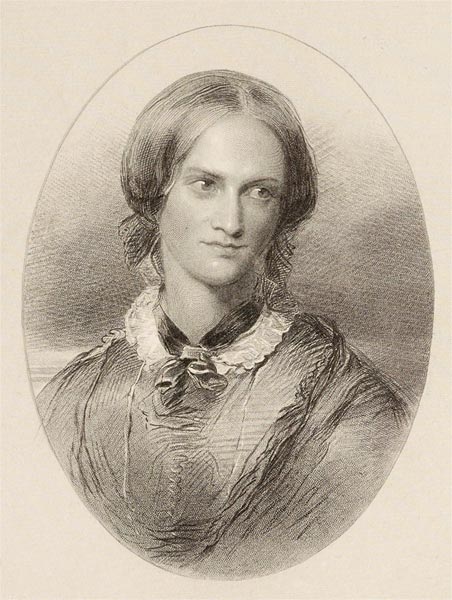

A Dark and Stormy Night: Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855). Fed up with teaching young girls their lessons, future novelist Charlotte Brontë began a diary entry that grew into a fictional fantasy.

A Dark and Stormy Night: Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855). Fed up with teaching young girls their lessons, future novelist Charlotte Brontë began a diary entry that grew into a fictional fantasy.

About the Diary

Charlotte Brontë's first job did not suit her fiery sensibility. At nineteen, with little heart for marriage and the need to earn a living, she began teaching at Roe Head School in the north of England, about twenty miles from her home in Haworth. She found the atmosphere stultifying and the pupils idiotic. Forced to maintain an outward semblance of professional grace, she concealed her considerable emotional energy and rage. One evening in February 1836, "after a day's weary wandering," she began a diary entry on a loose sheet of paper: "Well here I am at Roe-Head," she wrote, "it is seven o'clock at night, the young ladies are all at their lessons, the school-room is quiet, the fire is low, a stormy day is at this moment passing off in a murmuring and bleak night."

During this rare moment alone, Brontë confessed her feelings of alienation. "It is strange," she wrote, "I cannot get used to the ongoings that surround me. I fulfil my duties strictly & well," but "as God was not in the wind, nor the fire, nor the earth-quake, so neither is my heart in the task, the theme or the exercises." Over the course of her teenage years, Brontë had found a creative way to get through such uncomfortable moments. She had learned to listen to what she called the "still small voice alone that comes to me at eventide"—an imaginative voice that granted her escape and release. "It is that which wakes my spirit & engrosses all my living feelings," she wrote in this diary entry, "all my energies which are not merely mechanical, &, like Haworth & home, wakes sensations which lie dormant elsewhere."

Brontë recalled how the previous night's "stormy blast . . . whirled me away like heath in the wilderness for five seconds of ecstasy." While the others were at tea, she said, she approached an exotic palace in the kingdom of Angria, peered through the windows at a lushly appointed room, and observed a drunken man shamelessly stretched out on the queen's voluptuous ottoman. But this, of course, was pure invention. Having begun writing a straightforward diary entry—a real-time description of her life at Roe Head—Brontë had stepped seamlessly into fiction. She allowed her high-flown storytelling to provide an antidote to the dreary everyday, her diary serving as a gateway from the real world into the fantastical.

Ten years before she wrote this entry, Charlotte's brother Branwell had received a set of toy soldiers as a gift from their father. He and his sisters—Charlotte, Anne, and Emily—were delighted, and they did what children do: They named the soldiers and made up stories about them. But the stunningly imaginative Brontës took typical childhood play to a new level, spinning a complex series of interconnected tales in exotic settings, documenting their creations in tiny handmade books written in a minuscule script appropriate to the scale of their soldier-characters. Charlotte's and Branwell's invented world was called Angria, and it was to this kingdom (and this script) that she returned that evening in 1836 when took a much-needed break from her schoolroom duties.

This is one of several diary entries that Charlotte Brontë made during her three years teaching at Roe Head School. She folded the single sheet of paper to form four pages, each a bit smaller than a 5 x 7 inch photograph, and filled the space with nearly two thousand words. She packed explosive imagination into this miniature canvas, depicting herself as the breathless observer of the debauch of Quashia Quamina, one of the characters she and Branwell had created: "I watched the fluttering of his white shirt ruffles starting through the more than half-unbuttoned waistcoat." She emerged from the erotic reverie of the diary-story only when Miss Wooler—one of the schoolmistresses—appeared at the door with a plate of butter in her hand. "'A very stormy night my dear!' said she. 'It is ma'am,' said I."

Dear Diary, Dear Beloved: Frances Eliza Grenfell

Dear Diary, Dear Beloved: Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891). Forbidden to correspond with Charles Kingsley, the man she adored, Fanny Grenfell kept a diary in the form of unsent love letters instead.

Dear Diary, Dear Beloved: Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891). Forbidden to correspond with Charles Kingsley, the man she adored, Fanny Grenfell kept a diary in the form of unsent love letters instead.

About the Diary

Twenty-five-year-old Fanny Grenfell was drawn to the emerging Catholic revival movement in England and looked forward to a life of chastity. Cambridge undergraduate Charles Kingsley, son of an Anglican clergyman, was having serious doubts about his own faith. All that changed dramatically when the two met in 1839. Their passion for each other was strong and immediate. Fanny guided Charles into a firm embrace of Christian doctrine, and Charles convinced Fanny that sex—within the confines of marriage—was a sacred blessing.

The match was unacceptable to Fanny's family, and they sent her on a European tour to keep the two apart. Charles was poor and Fanny rich, and, to make matters worse, he was five years her junior. Forbidden to commit herself formally to Charles, Fanny did so surreptitiously: She began a journal in 1841, carrying it with her as she traveled, framing each entry as an intimate letter. She told the absent Charles that "for months this may not meet your eye, perhaps never!" and explained the purpose of her exercise: "if I die, this Journal will be a melancholy satisfaction to you, & if we are engaged, it will still be a pleasure to you to see how my mind & heart were employed in the long blank." She penned a warning on the first sheet: "To be given to C.K. in case of my death, unread by any other human being."

The journal became Fanny's outlet for the exalted feelings—"the inexhaustible torrent of my love"—that she was unable to express directly to her beloved. Using over 600 exclamation points to punctuate her breathless declarations, she wrote of their tenuous plans for a reunion ("I have been vibrating between Hope & Fear"), the strength of their love, even in separation ("time & space seem conquered & vanish away!"), and, occasionally, of the strain she felt in defying her family ("no man can appreciate the sacrifice a woman makes in a case like this"). Desperate for word from Charles, she dreamed that she had received a letter, but, upon opening it, "found it was my own writing inside — the Journal I had kept for you."

The journal became Fanny's outlet for the exalted feelings—"the inexhaustible torrent of my love"—that she was unable to express directly to her beloved. Using over 600 exclamation points to punctuate her breathless declarations, she wrote of their tenuous plans for a reunion ("I have been vibrating between Hope & Fear"), the strength of their love, even in separation ("time & space seem conquered & vanish away!"), and, occasionally, of the strain she felt in defying her family ("no man can appreciate the sacrifice a woman makes in a case like this"). Desperate for word from Charles, she dreamed that she had received a letter, but, upon opening it, "found it was my own writing inside — the Journal I had kept for you."

After they finally met for four days in January 1842, Fanny declared that "in you I have found Father, Mother, Friend, Husband!" After the embraces they had shared, Fanny's nights without Charles were a particular agony: "I stretch out my arms to you — & find you not — & then I fold my hands, those hands which have been clasped convulsively by yours, across my bosom, where that beloved head has rested – & the lips which you have kissed utter useless moans — & then I writhe under the intolerable consciousness that you are not near me"

At the beginning of her diary Fanny wrote a few lines from Romeo and Juliet: "O think it thou, we shall ever meet again—I doubt it not; & all these woes shall serve / For sweet discourses in our time to come!" But her story had a much happier ending than Shakespeare's tale of star-crossed lovers. The determined lovers endured separation, overcame familial opposition, and finally consummated their secretive courtship. Fanny Grenfell and Charles Kingsley wed in 1844, had four children, and enjoyed a passionate marriage, reconciling spiritual and carnal bliss. Charles became a successful clergyman, social reformer, and author of the popular works Westward Ho! and The Water Babies.

Diary of Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891), 1841–42. Gift of Sir John Pope-Hennessy in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Morgan, 1974.

Warning penned in the diary of Frances Eliza Grenfell (1814–1891), 1841–42. Gift of Sir John Pope-Hennessy in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Morgan, 1974.

Diary of a Marriage: Sophia and Nathaniel Hawthorne

Diary of a Marriage: Sophia (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864). Newlyweds Sophia Peabody and Nathaniel Hawthorne chose to keep a diary together, making a joint record of intimate life in their new home.

Diary of a Marriage: Sophia (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864). Newlyweds Sophia Peabody and Nathaniel Hawthorne chose to keep a diary together, making a joint record of intimate life in their new home.

About the Diary

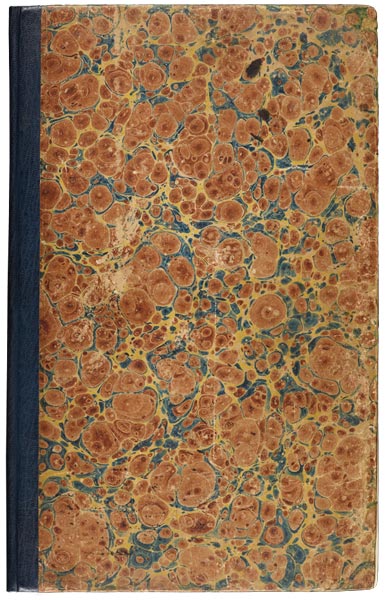

For the Hawthornes, journal keeping was a family affair. Both Nathaniel and Sophia kept private records periodically throughout their lives, and when they married in July 1842 they began to keep a journal together, each making entries in turn. They wrote in the same notebook—a small blank volume with marbled-paper covers and a leather spine—read each other's entries, and built a joint narrative of their intimate life as partners in their new home, the Old Manse in Concord.

"A rainy day—a rainy day," begins Nathaniel's first entry in their joint diary, "and I do verily believe there is no sunshine in this world, except what beams from my wife's eyes." While he teased Sophia about her hopeful disposition, he embraced his own new role as spouse with a sense of ease. "It is usually supposed that the cares of life come with matrimony;" he wrote, "but I seem to have cast off all care, and live on with as much easy trust in Providence as Adam could possibly have felt before he had learned that there was a world beyond his Paradise."

For her part, Sophia exalted in the physical pleasures of their union. When spring came, she compared nature's rebirth to her own awakening. "Oh lovely God!" she wrote, "I thank thee that I can rush into my sweet husband with all my many waters, & sing & thunder with all my waves in the vast expanse of his comprehensive bosom—How I exult there—how I foam & sparkle in the sun of his love. . . . I myself am Spring with all its birds, its rivers, its buds, singing, rushing, blooming in his arms. I feel new as the Earth which is just born again—I rejoice that I am, because I am his, wholly, unreservedly his." After Nathaniel's death, Sophia blotted out some of her own words in the notebook as she prepared her husband's journals for publication, but she left enough of herself uncensored that her soaring voice remained present.

As the seasons passed, the Hawthornes marked them together. "This is Thanksgiving Day," Nathaniel wrote on November 24, "a good old festival, and my wife and I have kept it with our hearts, and besides have made good cheer upon our turkey, and pudding, and pies, and custards, although none sat at our board but our two selves." When summer came, both tried their hand at gardening, and Sophia mocked her artistic husband as she observed him with rake in hand. "Dearest husband," she wrote, employing the formal language they often used to address each other, "thou shouldst not have to labour, especially with the hands, & thou hatest it rightfully. Thou art a seraph come to observe Nature & men in a still repose, without being obliged to exert thyself in clearing away old rubbish." Despite Sophia's protests, Nathaniel succeeded in bringing forth enough asparagus for dinner, and one day they shared a watermelon with Henry David Thoreau when he came for dinner.

On the first anniversary of their wedding day, the Hawthornes addressed love letters to each other within the diary. Sophia—pregnant with the couple's first child—recalled their lives the year before: "Then we had visions & dreamed of Paradise. Now Paradise is here & our fairest visions stand realized before us." Nathaniel, despite his chosen profession, felt powerless to capture the moment on paper: "life now heaves and swells beneath me like a brim-full ocean, and the endeavor to comprise and portion of it in words is like trying to dip up the ocean in a goblet."

When their first notebook was full, the Hawthornes began another—this one taller and narrower, but with a similar cover. In the first entry, Sophia wrote with joy of the arrival of their first child, Una. "It was great happiness to be able to put her to my breast immediately," she wrote, "& I thanked Heaven I was to have the privilege of nursing her." As the years went by and two more children were born, the Hawthornes contributed less and less to their common diary, but the changes to their family became physically evident in the volume. On the endpapers, the children added scribbles and drawings, and one day in 1852 eight-year-old Una made her own entry—a very short story about two little children taken in by a kind old lady after their parents died. She signed it, "Yours lovingly, Una."

When their first notebook was full, the Hawthornes began another—this one taller and narrower, but with a similar cover. In the first entry, Sophia wrote with joy of the arrival of their first child, Una. "It was great happiness to be able to put her to my breast immediately," she wrote, "& I thanked Heaven I was to have the privilege of nursing her." As the years went by and two more children were born, the Hawthornes contributed less and less to their common diary, but the changes to their family became physically evident in the volume. On the endpapers, the children added scribbles and drawings, and one day in 1852 eight-year-old Una made her own entry—a very short story about two little children taken in by a kind old lady after their parents died. She signed it, "Yours lovingly, Una."

Cover of the marriage diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864), 1842–43. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Cover of a diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864), kept after the birth of their first child, 1844–52. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Diary of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne (1809–1871) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864), with an entry by their daughter Una, s1844–52. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909.

Generation Gap: Paul Horgan

Generation Gap: Paul Horgan (1903–1994). As he observed the "self-flesh and self-sex absorption" of hippie culture in the late 1960s, novelist Paul Horgan confronted his own advancing age.

Generation Gap: Paul Horgan (1903–1994). As he observed the "self-flesh and self-sex absorption" of hippie culture in the late 1960s, novelist Paul Horgan confronted his own advancing age.

About the Diary

The so-called Summer of Love brought what Hunter Thompson called "freaks, heads, fun-hogs and weird night-people of every description" to Aspen, Colorado, in 1967 for "a wild and incredible dope orgy." The following summer, American writer Paul Horgan filled two small notebooks with his own observations of the hippie stragglers and wealthy tourists who uneasily shared the streets of Aspen. He felt a kinship with neither. "This summer I reflect on the pros and cons of intermittent loneliness," he wrote, "mostly the cons, naturally."

A historian, teacher, and prolific novelist, Horgan looked with a mix of astonishment and disdain at what he called the "half-naked, brick sun-burned, gold bearded, sex teasing, basically narcissistic" young people of Aspen, keenly aware of his own advancing age. "In 18 days I will be 65 years old," he wrote in his journal. "Aside from the wild, the offensive fact, I must recognize that I am no closer than ever in all these years to ease of connection with others" As he sat alone in restaurants, jotting down notes that might one day serve as grist for his fiction, he considered his motivation for this self-imposed separateness: "What is it in me," he wondered, "solitary in public places—which knows a sinking of the heart at overheard conversations between persons who are so intensely connected?" He concluded that this detachment was a boon to his fiction: "I observe intentionally from afar, and by the very factor of this distance, I must feel—and remember—the more keenly than if I rushed to embrace."

A historian, teacher, and prolific novelist, Horgan looked with a mix of astonishment and disdain at what he called the "half-naked, brick sun-burned, gold bearded, sex teasing, basically narcissistic" young people of Aspen, keenly aware of his own advancing age. "In 18 days I will be 65 years old," he wrote in his journal. "Aside from the wild, the offensive fact, I must recognize that I am no closer than ever in all these years to ease of connection with others" As he sat alone in restaurants, jotting down notes that might one day serve as grist for his fiction, he considered his motivation for this self-imposed separateness: "What is it in me," he wondered, "solitary in public places—which knows a sinking of the heart at overheard conversations between persons who are so intensely connected?" He concluded that this detachment was a boon to his fiction: "I observe intentionally from afar, and by the very factor of this distance, I must feel—and remember—the more keenly than if I rushed to embrace."

Horgan carried notebooks with him wherever he went to allow him to capture ideas at the moment they arose. "Some of the notes are productive," he later explained, "developing organically in a wonderful way. Others die and you don't know why. They all seem fascinating at the moment." In Aspen, he transcribed overheard comments—a server in gold lamé addressing a customer ("Now, your cork is absolutely sizzling to come out!"); two late-middle-age couples pontificating as they dined ("True banality . . . is only heightened by cocktails or the thermal nearness of others socializing"). As he traveled, he took note of bathroom graffiti, touched by anonymous scrawlings such as "the Lost Soul was here" or "I want a lover," in which he found "the simplest reduction of all longing which I have seen in words written by an anonymous hand. The hand speaks for all humanity."

Horgan carried notebooks with him wherever he went to allow him to capture ideas at the moment they arose. "Some of the notes are productive," he later explained, "developing organically in a wonderful way. Others die and you don't know why. They all seem fascinating at the moment." In Aspen, he transcribed overheard comments—a server in gold lamé addressing a customer ("Now, your cork is absolutely sizzling to come out!"); two late-middle-age couples pontificating as they dined ("True banality . . . is only heightened by cocktails or the thermal nearness of others socializing"). As he traveled, he took note of bathroom graffiti, touched by anonymous scrawlings such as "the Lost Soul was here" or "I want a lover," in which he found "the simplest reduction of all longing which I have seen in words written by an anonymous hand. The hand speaks for all humanity."

In 1973, Horgan published Approaches to Writing, a book of "shop talk" in which he explored his creative process. He mined his own journals—including the 1968 Aspen notebooks—for a selection of 408 numbered excerpts, avoiding his most personal entries but including ideas for stories, pronouncements on the nature of art, and—alongside curmudgeonly complaints about the state of literature and society—flashes of compassion: "We should pray for every single human creature we pass in the street. Each has an internal history so complicated that—truly—only God the Creator can sort out its elements and make judgments."

Diaries of Paul Horgan (1903–1994), 1972–74. Gift of the author, 1979.

Diary of Paul Horgan (1903–1994), 1968. Gift of the author, 1979.

Diary of Paul Horgan (1903–1994), 1968. Gift of the author, 1979.

Spinning and Sausage-making: Elizabeth Eastman Morgan

Spinning and Sausage-making: Elizabeth Eastman Morgan (b. 1795). Elizabeth Morgan tracked the rhythms of small-town life—from pig-butchering to candle-making—in early nineteenth-century Massachusetts.

Spinning and Sausage-making: Elizabeth Eastman Morgan (b. 1795). Elizabeth Morgan tracked the rhythms of small-town life—from pig-butchering to candle-making—in early nineteenth-century Massachusetts.

About the Diary

Like many nineteenth-century Americans, Elizabeth Eastman Morgan jotted a few lines each day to commemorate the day's weather and activities. Unmarried, living with her mother in West Springfield, Massachusetts, Morgan spent her time working at home, managing household finances, visiting with family and friends, and attending town meetings. For her, keeping a diary was a personal discipline—much in the tradition of a tradesman's log or annotated almanac—rather than an exercise in self-exploration. Morgan and her two married half-sisters had each inherited $160 from their father, a justice of the peace, and she kept careful track of her income from the sale of butter and cheese.

From 1818, when she was twenty-three, until 1843, Morgan filled nearly five hundred pages in nine booklets folded and sewed by hand, dating each page neatly and drawing lines between entries. The newspapers that served as covers for some of her notebooks brought national and international news as well as concerns of the day, such as the need for "every farmer, gardener, and house keeper to declare a war of extermination against worms, bugs, and other mischievous and devouring insects." (The recommended killers included tobacco and old urine.)

Although little changed in Morgan's life over the course of sixteen years, she marked the rhythm of the seasons, noting the appearance of green peas in June and ripe peaches and whortleberries in August. In March she began to hear bluebirds; in April she would hear frogs "peep" for the first time; swarms of bees sometimes appeared in summer. Autumn was a time for making cider and applesauce, and a hog was generally butchered in December. Housework never ended: Morgan made soap and candles; picked, carded, and spun wool; baked, pickled, churned, and brewed; and spent a great deal of time washing and ironing clothes.

Morgan listed local births, marriages, and deaths, taking special note of unusual circumstances. In 1819, she described two suicides on a single page. "This evening we here [sic] the news that Mr John Dickinson of Granby has put a period to his life by hanging himself in his cornhouse with a rope, he was considered to be in a derangd state of mind." And Lucius Day was found with his throat cut; "they say he is apt to have crazy turns."

Elizabeth Morgan's great-great-grandfather, Miles Morgan, was one of the first Europeans to settle the town of Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1644, and her cousin Joseph—who co-founded the Aetna fire insurance company during the period that Elizabeth kept these diaries—was the grandfather of Pierpont Morgan, the American financier.

Diaries of Elizabeth Eastman Morgan (born 1795), 1818–34. Archives of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Amazing Grace: John Newton

Amazing Grace: John Newton (1725–1807). Once a slave trafficker, John Newton felt called to the ministry and wrote the most enduring hymn of all time—"Amazing Grace." He kept a copious diary of his spiritual progress.

Amazing Grace: John Newton (1725–1807). Once a slave trafficker, John Newton felt called to the ministry and wrote the most enduring hymn of all time—"Amazing Grace." He kept a copious diary of his spiritual progress.

About the Diary

Since it was first published in 1779, "Amazing Grace" has become a global anthem of deliverance, and the life of its author, John Newton, a paradigm of spiritual awakening. Arlo Guthrie closed his set at the 1969 Woodstock festival with the hymn, echoing the words sung by countless protestors in the civil rights movement, and has continued to perform it frequently. As he introduces the song, Guthrie often tells a story about its author, saying that Newton was a slave trafficker who experienced an epiphany in the middle of the ocean, turned his boat around, and brought everyone back home, memorializing his enlightenment in song. But Guthrie's version of the story, while compelling, is not accurate. While it is true that Newton played an active role in the slave trade, underwent a dramatic spiritual conversion, and wrote the lyrics to the famous hymn, his personal story—extraordinary as it is—did not unfold quite so neatly.

Newton pledged his life to God after surviving a maritime disaster in 1749, but for several years thereafter he commanded ships conveying enslaved Africans. He retired only when his health forced him to remain on solid ground, settling in Liverpool with his wife. There he began a new diary in September 1756, noting that "it is a very useful method to take some account of every day." Over the next sixteen years, Newton filled every inch of over four hundred folio pages with near-daily reports of this transformative period in his life but never made reference to his former occupation. Many years later he was convinced of the heinousness of slavery and raised his voice in opposition. He lived to see the British slave trade outlawed—just months before his death in 1807.

Newton's sense that God's boundless grace had saved him from a life of metaphoric blindness pervades the diary. He prayed in secret, read scripture, taught himself Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac, and worshipped assiduously but always fell short in his own estimation, lamenting—in words that echo his famous hymn—"what a wretch I am." Newton often read over past diary entries to chart his spiritual progress, and an early reader of his manuscript added a handwritten index that cataloged some of his repeat offenses, such as "abstraction," "sleeping too long" (one of Newton's worst vices), and "talking too much."

When the controversial preacher John Wesley came to town, Newton was energized by his example and began to feel that he, too, might be called to the ministry. As he awaited a clear calling, Newton had a choice to make: Should he follow the lead of the independent evangelicals, whose style clearly fired his soul, or seek ordination in the established church, where he found the preaching uninspired? Despite misgivings, he decided to seek Anglican ordination but had trouble securing the necessary testimonials ("they are all afraid to own a suspected Methodist"). When his application was rejected, he was crushed. He began to preach at home on Sunday evenings—first for his family, then for a handful of friends, and soon for a packed room.

When the controversial preacher John Wesley came to town, Newton was energized by his example and began to feel that he, too, might be called to the ministry. As he awaited a clear calling, Newton had a choice to make: Should he follow the lead of the independent evangelicals, whose style clearly fired his soul, or seek ordination in the established church, where he found the preaching uninspired? Despite misgivings, he decided to seek Anglican ordination but had trouble securing the necessary testimonials ("they are all afraid to own a suspected Methodist"). When his application was rejected, he was crushed. He began to preach at home on Sunday evenings—first for his family, then for a handful of friends, and soon for a packed room.

Newton eventually achieved ordination and was assigned to a parish in the town of Olney. As early as October 1765 he was writing hymns to accompany particular Biblical texts: "I am sometimes forced to make a few lines myself, when I cannot suit the text from the books I have."

He concluded this diary in 1766 with a sense of gratitude and astonishment: "It is more than 16 years since I began to write in this book. How many scenes have I past thro in the Time. By what a way has the Lord led me, what wonders has he shewn me!" Newton hoped that his life—as described in a lifetime of diaries—would serve as inspiration to others. He asked God to "give a History to all who may read these records of thy Goodness, & my own vileness."

John Newton (1725–1807). Olney Hymns. London: W. Oliver, 1779. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

Index to the diary of John Newton (1725–1807), 1756–72. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913.

Niagara Honeymoon: Mary Ann and Septimus Palairet

Niagara Honeymoon: Mary Ann and Septimus Palairet (1800s). A newly married couple from England traveled through America during the 1840s and recorded their impressions in words and pictures.

Niagara Honeymoon: Mary Ann and Septimus Palairet (1800s). A newly married couple from England traveled through America during the 1840s and recorded their impressions in words and pictures.

About the Diary

Mary Ann and Septimus Palairet of Bradford-on-Avon embarked on a honeymoon tour of the eastern United States and Canada in 1843. They created a travel diary together, with text by Mary Ann and drawings by Septimus, in a lovely album with a gold-tooled purple cover. "A fortnight might be spent in sketching, a book filled," Mary Ann wrote, "and yet there would be still subjects for the pencil left." Much like today's travel photographs or mobile updates, the Palairets' travelogue was probably not meant to be kept private—their highly polished account was no doubt shared with friends and family upon their return to England.

During a trip up the Hudson River on the steamboat Empire ("for such is the great Anti-Republican name," Mary Ann quipped) with a stop at West Point, the Palairets marveled at the young country's rapid development. In Rochester, Mary Ann observed a flourishing town "where some thirty years ago was a forest, peopled only by wild beasts or perchance a few Indians." Indeed, the Palairets bore witness to a period of unprecedented growth in transportation, communication, and invention in the United States. "During our travels we have seen the country in every stage of progress towards civilization," Mary Ann wrote, "from the natural forest to the cultivated fields or the busy town."

In their choice of a honeymoon destination, the Palairets were inspired by the example of their famous compatriot Charles Dickens, whose American Notes had appeared the year before. In fact, they passed on the opportunity to inspect a prison in Auburn, New York, "seeing that Mr. Dickens has described it for the benefit of all travelers." It was an era in which European comment on American culture abounded: Frances Trollope had published her Domestic Manners of the Americans in 1832, and Alexis de Tocqueville's celebrated Democracy in America—the most enduring of all nineteenth-century commentary on the young United States—was published in English in two volumes in 1835 and 1840.

Like many travelers, the Palairets revealed their national prejudices. They were appalled at the hotels' meal schedule: "the American houses are so uncivilized—breakfast 7, dinner 1 or 2, and tea 5 or 6—and if any one is not ready to appear at the prescribed times, he stands a considerable chance of doing penance for his sin of idleness or forgetfulness." So when they reached Kingston, Ontario—a town with comfortable echoes of home—Mary Ann was delighted to find that dinner was "served up at 6!! There's a stride in civilization!"

Like many travelers, the Palairets revealed their national prejudices. They were appalled at the hotels' meal schedule: "the American houses are so uncivilized—breakfast 7, dinner 1 or 2, and tea 5 or 6—and if any one is not ready to appear at the prescribed times, he stands a considerable chance of doing penance for his sin of idleness or forgetfulness." So when they reached Kingston, Ontario—a town with comfortable echoes of home—Mary Ann was delighted to find that dinner was "served up at 6!! There's a stride in civilization!"

Even American children were found wanting. Mary Ann considered the Québécois youth "strikingly beautiful, especially to those who have been traveling in the 'States,' where infantine loveliness is scarcely to be seen." Despite the couple's strong sense of Canadian superiority, they were surprised to find French spoken there among the "lower orders." The French Canadians are "a very idle and dirty set, always lounging about in the market places," Mary Ann noted. "In fact Septimus became quite angry with them for not talking English, which they all can do."

But Mary Ann reserved her most scathing review for the French soprano Jeanne-Anaïs Castellan, who performed in the Thousand Islands during the Palairets' tour. "The American public have made such a fuss about the cantatrice and our Philadelphia friends pitied us so much for being unable to attend two concerts she gave there," Mary Ann wrote, "that we were unwilling to miss this opportunity of hearing her—especially as she is declared second only to Malibrau. Alas for Malibrau! I almost expected to see her ghost rise and like Banquo's 'push us from our stools' for sitting to listen to such a vulgar screamer."

Mary Ann considered herself a hardy traveler and noted with pride when a guide praised her English fortitude. She especially enjoyed walks around Niagara Falls, already a honeymoon destination by the early nineteenth century. Its glories surpassed her expectations a hundredfold: "To attempt a description of Niagara so as to give any idea of its sublimity is quite beyond the powers of the greatest writer that ever lived, and I shall certainly not be guilty of such an absurdity," Mary Ann admitted. "We gazed at the glorious sheet of falling waters, dashing down and losing itself in foam and spray which reflected back the sun's rays in the most brilliant rainbow ever seen, until we were suddenly reminded that we must hasten back to dinner. How very humiliating it is that such a thing as hunger will intrude itself even at Niagara!"

By the end of the honeymoon trip, Mary Ann and Septimus were likely expecting a child. Their son, Henry, was born in 1844, and Annie and Eleanor followed a few years later.

Cover of the diary of Mary Ann and Septimus Palairet, 1843. Gift of Arnold Whitridge, 1962

Self-portrait by Mary Ann Palairet, from the diary she kept with her husband, Septimus, 1843. Gift of Arnold Whitridge, 1962.

Fighting for Sanity: John Ruskin

Fighting for Sanity: John Ruskin (1819–1900). After recovering from a psychotic break, English critic John Ruskin was determined to remain stable and continue to work. He tracked his health in his diary.

Fighting for Sanity: John Ruskin (1819–1900). After recovering from a psychotic break, English critic John Ruskin was determined to remain stable and continue to work. He tracked his health in his diary.

About the Diary

Fifty-seven-year-old John Ruskin, the great English critic, started a new diary in 1876. He wrote in a tall, narrow volume—just over a foot high and six inches wide—with printed page numbers on the ruled leaves and the word "ledger" stamped on the spine. As the year began, he was characteristically busy juggling a multitude of projects, from scholarly pursuits to social initiatives, such as classifying minerals for a new museum to serve the local working class. For nearly seven years he turned to this diary almost daily whenever he was at Brantwood, his home in the Lake District of England, sometimes using a different volume to keep track of his days when he was away teaching or traveling.

Ruskin found himself "crushed under business," often languid and depressed, but open to the beauty of nature—from an "exquisite broad rainbow" to a bright sunset or a new moon that shone like limelight. With the local ironworks spewing waste into the air around his home, Ruskin felt oppressed by the industrial darkness: "Black — black — black — soot and rain mixed—and my own mind in some ways like it."

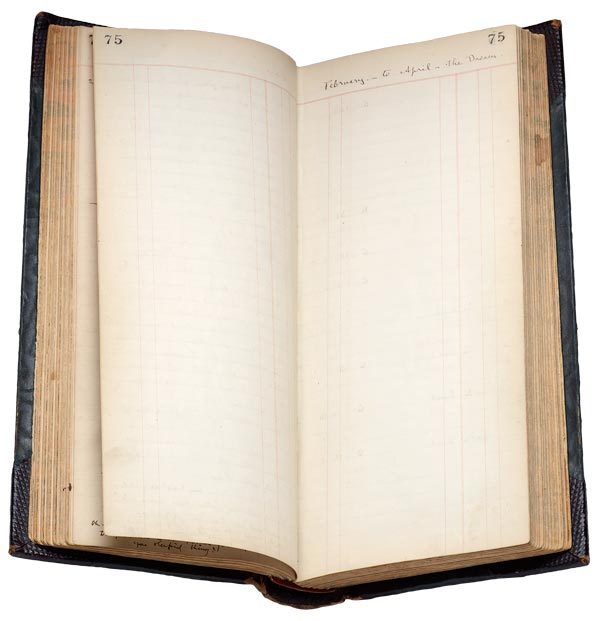

By early 1878, Ruskin was in a fragile state, feeling "cold and dead," losing interest in those aspects of life that once gave him joy. Even the diary seemed a fruitless exercise as he watched "how the useless mass accumulates." He confessed to feeling a "perpetual fog and depression of my total me—body and soul,—not in any great sadness, but in a mean, small, withered way." In late February, Ruskin collapsed. For over a month he lay prostrate, tormented by psychotic nightmares, paralyzed by a sense of his own worthlessness. His diary lay untouched. When he emerged from his room in early April, he picked up the volume and made a simple entry on two pages left otherwise blank: "February to April—the Dream." He was ready to reenter life.

By early 1878, Ruskin was in a fragile state, feeling "cold and dead," losing interest in those aspects of life that once gave him joy. Even the diary seemed a fruitless exercise as he watched "how the useless mass accumulates." He confessed to feeling a "perpetual fog and depression of my total me—body and soul,—not in any great sadness, but in a mean, small, withered way." In late February, Ruskin collapsed. For over a month he lay prostrate, tormented by psychotic nightmares, paralyzed by a sense of his own worthlessness. His diary lay untouched. When he emerged from his room in early April, he picked up the volume and made a simple entry on two pages left otherwise blank: "February to April—the Dream." He was ready to reenter life.

For the rest of year he made only a few brief notes in the diary, but resumed his practice of daily jottings in January 1879. As the anniversary of his mental collapse approached, he was wary but grateful. He watched a fresh white snow melt to "grey waste" and cautioned himself, "Let me see that I don't thaw away into waste myself, now the Spring's come again for me, once more!" By March he felt "depressed enough, but knowing my battle now better than when it beat me last year." When he marked the second anniversary of his reemergence in 1880, he embraced the coming spring: "Two years since I began to wake from the long dream. Primroses and violets just in sweet beginnings, and periwinkles beaming in my ivy bank, made me happy yesterday."

As the years passed, Ruskin suffered several additional breakdowns, though none as dramatic as the 1878 nightmare. After one episode in 1881, he wrote to a friend, "I CAN'T understand how so extremely rational a person as I am can lose their wits, and still more, how they don't know they have lost them at the time. I do think if I were to go crazy again for the third time I should know I was so." His was determined to study his own patterns and learn enough about himself to remain sane, and he used the diary as a tool to that end.

He reread his earlier entries, searching for signs leading up to his breakdown, underlining key words and phrases, compiling an index of his experience, and putting down on paper all he could remember of his psychotic visions. When he had filled all the right-hand pages of the diary, he went back to the beginning of the book and began filling the left-hand pages, so that his new entries appeared opposite entries from past years, forcing him to confront—and comment on—his younger self. In his final entry, written on January 1, 1884, Ruskin greeted the new year with optimism: "Tuesday. Very thankful to be spared to see the light, and begin the labour, not unhopefully, of this New Year."

John Ruskin (1819–1900), Self-Portrait, in Blue Neckcloth, Watercolor and gouache, Gift of the Fellows; 1959.23

Diary entry made by John Ruskin (1819–1900) after his 1878 breakdown. Bequest of Helen Gill Viljoen, 1974.

Final Years of a Full Life: Sir Walter Scott

Final Years of a Full Life: Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832). Sir Walter Scott spent the last years of his life furiously writing himself out of debt and resisting the "cold sinkings of the heart" that periodically dogged him.

Final Years of a Full Life: Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832). Sir Walter Scott spent the last years of his life furiously writing himself out of debt and resisting the "cold sinkings of the heart" that periodically dogged him.

About the Diary

"I am enamourd of my Journal. I wish the zeal may last." Scott made this entry the day after opening his new blank book for the first time. "Behold I have a handsome locked volume such as might serve for a Lady's album." He took up the practice of daily personal writing in 1825, at age fifty-four, perhaps inspired by the prolific example of Samuel Pepys, whose diary had just been deciphered and published for the first time. Scott regretted having begun the journal so late in life and resolved to create a record, not only for himself, but also for "my family and the public," to capture the memory of his days. He cited Byron as the model for his style—"throwing aside all pretence to regularity and order and marking down events just as they occurd to recollection."

Scott's zeal for the practice did, indeed, last—until the final months of his life. Over a period of six years, the journal became a crucial outlet for the feelings of despair—the "cold sinkings of the heart"—that had agonized him from the time of his youth. "Is it the body brings it on the mind or the mind inflicts it upon the body?" he wondered, concluding that the two are inseparable: "I fancy I might as well enquire whether the fiddle or the fiddlestick makes the tune." Scott found that the only effective remedy for depression was physical exertion. "Fighting with this fiend is not always the best was to conquer him," he wrote. "I have always found exercize and the open air better than reasoning." His long walks often led to dramatic emotional recovery: "The freshness of the air, the singing of the birds, the beautiful aspect of nature, the size of the venerable trees, gave me all a delightful feeling this morning. It seemd there was pleasure even in living and breathing without anything else."

The famous Sir Walter seemed to know all his prominent contemporaries, from Lord Byron ("I believe that he embellished his own amours considerably") to Lord Buchan ("a person whose immense vanity bordering upon insanity obscured or rather eclipsed very considerable talents"), and he read voraciously, commenting on the works of Jane Austen ("What a pity such a gifted creature died so early") and William Wordsworth ("there is a freshness, vivacity and spring about [his] mind"). Reports of visits with literary luminaries and heads of state stand side by side in Scott's journal with accounts of the everyday country life he passionately preferred: "I wish for a sheep's head and a whiskey-toddy against all the French cookery and Champagne in the world."

The famous Sir Walter seemed to know all his prominent contemporaries, from Lord Byron ("I believe that he embellished his own amours considerably") to Lord Buchan ("a person whose immense vanity bordering upon insanity obscured or rather eclipsed very considerable talents"), and he read voraciously, commenting on the works of Jane Austen ("What a pity such a gifted creature died so early") and William Wordsworth ("there is a freshness, vivacity and spring about [his] mind"). Reports of visits with literary luminaries and heads of state stand side by side in Scott's journal with accounts of the everyday country life he passionately preferred: "I wish for a sheep's head and a whiskey-toddy against all the French cookery and Champagne in the world."

Scott began his journal shortly before the country-wide financial crisis that forced him to spend his final years writing himself furiously out of debt. "I am become a sort of writing Automaton," he noted, and his daily entries indeed reveal an astonishing creative stamina. A series of strokes in the early 1830s slowly deprived him of control over his speech and handwriting but not of his awareness of his own decline. "I am not the man that I was," he admits, finally acknowledging that "The plough is coming to the end of the furrow."

Portrait of Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), engraved by by M.J. Dansforth after a painting by C.R. Leslie

Cover of the diary of Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832), 1825–32. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, ca. 1900.

Pride and Piracy: Bartholomew Sharpe

Pride and Piracy: Bartholomew Sharpe (ca. 1650–1690). As he terrorized Spanish towns and ships in the Americas, English pirate Bartholomew Sharpe kept a diary of his voyage and his exploits.

Pride and Piracy: Bartholomew Sharpe (ca. 1650–1690). As he terrorized Spanish towns and ships in the Americas, English pirate Bartholomew Sharpe kept a diary of his voyage and his exploits.

About the Diary

In 1680 a band of English pirates sailed along the west coast of South America in what was then known as the South Sea, wreaking terror and destruction on Spanish ships and villages. Bartholomew Sharpe, the expert navigator who served as their captain, kept a diary of the voyage and his exploits. When he returned to England in 1682, he stood trial for piracy and murder, but was acquitted on a technicality after handing over a document that was of great value to King Charles II: a hand-drawn chart book—or derrotero—seized from the Spanish ship Rosario. The Spaniards "were a-goeing to throw [it] overboard," Sharpe's diary reads, "but my men prevented it, which made the Spanish Captain cry out, 'fare well South Sea.'" This chart book was truly pirate's treasure: it provided the English with invaluable intelligence (and an edge over the dominant Spanish) in an era when various European powers vied for supremacy in the Americas.

The volume pictured here, bound in fine red leather, is one of several beautiful manuscript copies of Sharpe's diary that were made for presentation to members of the royal court after Sharpe turned over the valuable derrotero. The copy was made by chartmaker William Hacke, whose artistry turned Sharpe's humble diary into an object of luxe and his experience into a tale of glory. Sharpe's shipboard diary does not survive, so it is impossible to know for certain how closely this recopied version adheres to the original text. But we can be sure that this copy, with its many florid passages, was heavily enhanced to highlight Sharpe's bravery and patriotism.

Sharpe's voyage began in April 1680, when he gathered a band of buccaneers to cross the isthmus of Darien (in present-day Panama) on foot, tracing the path that the notorious Henry Morgan had blazed several years before. Sharpe enlisted the help of the local natives to guide his band overland. "The people for the most part are very handsom," this copy of his diary reads, "especially the female sex, and as they are very beutifull so they are allso very free to dispose of themselves to Englishmen answering them in all respects according to their desire." After several days with "nothing but the cold earth for our Lodgings, and for our covering the green trees," Sharpe's men sacked a Spanish town and finally "beheld the faire South Sea."

Sailing in ships they had commandeered from the Spanish, Sharpe and his band proceeded south along the west coast of Central and South America, seeking their fortune with violent abandon. After attacking a Chilean town ironically named La Serena, Sharpe boasted of the prowess of his vastly outnumbered band. "I agreed with the Spaniards for the redemption of this city," the diary reads. "They were to pay me the sum of 80,000 Pieces of Eight—but insteed of that they rallied 4 or 500 hors[es] to take us all prisoners. But I marched out with my men & fought them & beat them to their hearts content, after which I set the city on fire & burnt it & came away by the light of it."

If Sharpe was a ruthless thief and murderer, he was also an accomplished navigator. He was the first English sailor to make the treacherous voyage around Cape Horn from the west, guiding his fleet through horrendous weather conditions and his men through severe privation—"nothing but dowboys & tallow for dinner & supper." They had saved a hog to kill for Christmas dinner, but after many difficult months the crew was ready to mutiny if they didn't reach the Caribbean islands soon. Sharpe promised to eat the ship's dog if they didn't see land within three days—and he made it, finally arriving in Barbados and giving the ship to those pirates who had already gambled away their booty. Sharpe returned to England, ready to face trial if need be, secure in the knowledge that he had a valuable chart book in hand with which he might buy his freedom.

Sharpe was not the only buccaneer to keep a diary of the voyage. Several accounts survive, the best-known of which is that of Basil Ringrose, which was published as the second volume of the English edition of Alexandre Exquemelin's bestselling History of the Bucaniers of America. Over three centuries later, the image of swashbuckling pirate—as portrayed in Exquemelin's work and in this version of Sharpe's journal—endures in film, fantasy, and the popular imagination.

Title page of an illustrated manuscript of Bartholomew Sharpe's diary, made by William Hacke, 1680s. Gift of H.P. Kraus, 1979.

Sex, Drugs, and Ennui: Tennessee Williams

Sex, Drugs, and Ennui: Tennessee Williams (1911–1983). At the height of his literary success, dramatist Tennessee Williams was full of anxiety and dependent on drugs and alcohol. His diary revealed his inner anguish.

Sex, Drugs, and Ennui: Tennessee Williams (1911–1983). At the height of his literary success, dramatist Tennessee Williams was full of anxiety and dependent on drugs and alcohol. His diary revealed his inner anguish.

About the Diary

In February 1955 Tennessee Williams made his first entry in a cheap Italian exercise book with a cover featuring white polka dots on a blue background. "A black day to begin a blue journal," he wrote. From the time he started keeping a diary regularly in 1936, he had recorded such black and blue days—periods of low spirits and depression during which he was dogged by what he called his "blue devils." Though he sometimes read over past entries in disgust at his own "pusillanimous whining," the journals served as Williams' essential companion, a place to surrender to feelings of self-doubt, loneliness, and longing.

Now a prize-winning playwright after years of striving and wandering, he found himself unable to embrace success. As he watched Elia Kazan direct his new play, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, in rehearsal, he felt "hellish—just about hanging on by the skin of my teeth." He found the lead actress, Barbara Bel Geddes "inadequate," while Burl Ives, as Big Daddy, "acted like a stuffed turkey." He considered the set in Philadelphia, where the play was in previews, "a meaningless piece of chi chi." The play opened to rave reviews (later winning both the Pulitzer Prize and New York Drama Critics' Award), but Williams felt only fatigue. "You see," he wrote, "I have nothing to say. The play production and its tensions drained every thing out of me. I have nothing to record but the continuity of days. They do continue, and I continue with them."

Williams made plans to escape to Europe: "Tomorrow, little blue book, we go to sea again and start another one of our strange, haunted summers in lovely Rome." Once in Rome, he made a stark entry: "Internal state: ominous." Calling himself "small, self-contained, somewhat dead, cold person, a sort of a lunar personality without the shine," he realized that only "some radical change can divert the downward course of my spirit, some startling new place or people to arrest the drift, the drag." He summoned his courage, traveled, swam, read D. H. Lawrence, and cruised. Still, by August, he had "nothing to say except I'm still hanging on."

In Hamburg in early September, he awaited a lover in his hotel after consuming a "pinkie" (Secanol), a double martini, and a scotch. After that night, he began writing in a different notebook but returned to this one two years later. Reading over his last entry from 1955 ("I've closed the drapes on the window so I can rest, and wait in a comforting twilight"), he wrote, "how nice that sounds to me now." He was again in a state of "imminent crack-up," traveling maniacally, feeling the impulse to "fly away," and above all, feeling "Lonely! Very lonely!" Still, he was writing again—a new play, Sweet Bird of Youth—and even in the face of chronic depression he ended many of his entries with his trademark signoff, a call to move forward: "En avant!"

Replica of the pattern on the cover of the diary of Tennessee Williams (1911–1983), 1955–58.