Alice: 150 Years of Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was first published in 1865, but the story originated three years earlier during a boating trip one perfect English summer afternoon.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (better known by his penname Lewis Carroll) and Robinson Duckworth, both young Oxford dons, were rowing the three Liddell sisters—Alice, Lorina, and Edith—up the River Thames to the hamlet of Godstow for a picnic. Along the way, the girls asked for a story.

Storytelling frequently enlivened their outings, and Carroll readily obliged. With no idea what would follow, he sent his heroine “straight down a rabbit-hole, to begin with, without the least idea what was to happen afterwards,” and the narrative of Wonderland emerged over the long afternoon. At the end of the day, ten-year-old Alice asked for a written copy of the story.

Carroll drafted an outline the following day and finished the text within a few months. But, keenly attuned to the importance of pictures in a children’s book, he worked on the story’s illustrations for more than two years. The manuscript, titled “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground,” was finally completed and given to Alice in 1864.

An early draft was shared with the fantasy children’s writer George Macdonald, whose young son Greville so loved the tale that he “wished there were 60,000 volumes of it.” Macdonald and other friends encouraged Carroll to publish, and he did so the next year, after revising the book to twice its original length and commissioning John Tenniel, one of the best illustrators of the day, to re-do the pictures. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland appeared on 4 July 1865, exactly three years after the famous boating trip.

One early copy was seen by John Tenniel, who was shocked to find his pictures badly reproduced. He wrote Carroll immediately and objected so strongly that the author resolved to withdraw the entire edition—a radical decision, since Alice was essentially a self-published book. Carroll estimated he would have to sell four thousand copies just to break even, and he feared that for an unknown debut novelist this was “too much to hope for.”

Nevertheless, he went ahead, and a new edition appeared only a few months later to immediate and lasting success. The book, which has never been out of print, has had an enormous impact on children’s literature and popular culture. The characters have been readily adapted and reinterpreted in countless ways. Alice is a strong and intriguing heroine, and it is easy to identify with the young protagonist as she learns to navigate the world.

In this online exhibition, we invite you to learn about Alice, Lewis Carroll, and the history of the original manuscript; trace the development of the iconic illustrations; page through a selection of manuscripts and letters; watch early film adaptations, and listen to Alice-inspired music.

Share your own Wonderland experience: #Alice150 #WonderlandNYC

This online exhibition is presented in conjunction with the exhibition Alice: 150 Years of Wonderland on view 26 June to 11 October 2015, organized by Carolyn Vega, Assistant Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

“Why is a raven like a writing-desk?”

Hand-colored proof, 1885

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, 2005.198.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Transcriptions

Read transcriptions of the letters and manuscripts in the exhibition.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Postcard to Mary Mileham, signed in reverse “C.L.D.” and dated Eastbourne, 14 September 1884

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, MA 8624.1

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015

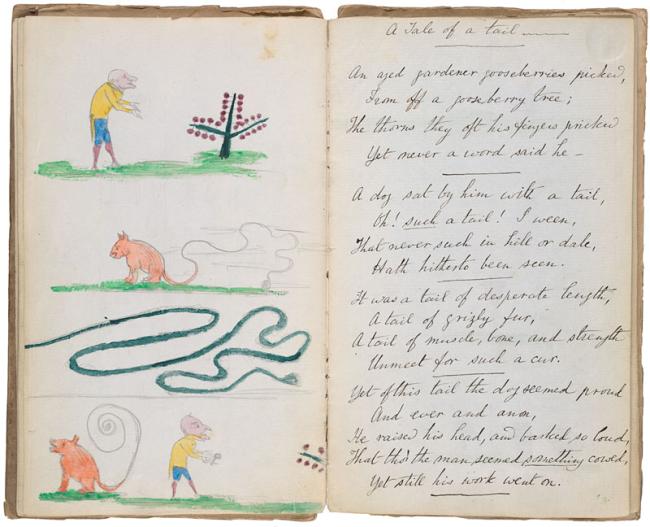

Carroll’s “Tale of a Tail”

This humorous poem appears in Carroll’s earliest surviving manuscript, a magazine he created for his younger siblings when he was just thirteen years old.

A Tale of a tail—

------

An aged gardener gooseberries picked,

From off a gooseberry tree;

The thorns they oft his fingers pricked

Yet never a word said he—

------

A dog sat by him with a tail,

Oh! such a tail! I ween,

That never such in hill or dale,

Hath hitherto been seen.

------

It was a tail of desperate length,

A tail of grizly fur,

A tail of muscle, bone, and strength

Unmeet for such a cur.

------

Yet of this tail the dog seemed proud

And ever and anon,

He raised his head, and barked so loud,

That tho’ the man seemed something cowed,

Yet still his work went on.

------

At length in lashing out its tail,

It twisted it so tight,

Around his legs, 'twas no avail,

To pull with all its might.

------

The gardener scarce could make a guess,

What round his legs had got,

Yet he worked on in weariness,

Although his wrath was hot.

------

“Why, what’s the matter?” he did say,

“I can’t keep on my feet,

‘Yet not a glass I’ve had this day

‘Save one, of brandy neat.

------

“Two quarts of ale, and one good sup,

‘Of whiskey sweet and strong,

‘And yet I scarce can now stand up,

I fear that something’s wrong.

------

His work reluctantly he stopped,

The cause of this to view,

Then quickly seized an axe and chopped,

The guilty tail in two.

------

When this was done, with mirth he bowed

Till he was black and blue,

The dog it barked both long and loud,

And with good reason too.

Moral. Don’t get drunk.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Useful and Instructive Poetry

Autograph manuscript, dated [Croft Rectory, Yorkshire, 1845]

Alfred C. Berol Collection, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Carroll’s “Photography Extraordinary”

Carroll’s humorous essay “Photography Extraordinary” was first published anonymously in an 1855 issue of The Comic Times

The recent extraordinary discovery in Photography, as applied to the operations of the mind, has reduced the art of novel-writing to the merest mechanical labour. We have been kindly permitted by the artist to be present during one of his experiments; but as the invention has not yet been given to the world, we are only at liberty to relate the results, suppressing all details of chemicals and manipulation.

The operator began by stating that the ideas of the feeblest intellect, when once received on properly prepared paper, could be “developed” up to any required degree of intensity. On hearing our wish that he would begin with an extreme case, he obligingly summoned a young man from the adjoining room, who appeared to be of the very weakest possible physical and mental powers. On being asked what we thought of him, we candidly confessed that he seemed incapable of anything but sleep: our friend cordially assented to this opinion.

The machine being in position, and a mesmeric rapport established between the mind of the patient and the object glass, the young man was asked whether he wished to say anything; he feebly replied “Nothing.” He was then asked what he was thinking of, and the answer, as before, was “Nothing.” The artist on this pronounced him to be in a most satisfactory state, and at once commenced the operation.

After the paper had been exposed for the requisite time, it was removed and submitted to our inspection; we found it be covered with faint and almost illegible characters. A closer scrutiny revealed the following:—

“Alas! she would not hear my prayer!

Yet it were rash to tear my hair;

Disfigured, I should be less fair.

“She was unwise, I may say blind;

Once she was lovingly inclined;

Some circumstance has changd her mind.”

There was a moment’s silence; the pony stumbled over a stone in the path, and unseated his rider. A crash was heard among the dried leaves; the youth rose; a slight bruise on his left shoulder, and a disarrangement of his cravat, were the only traces that remained of this trifling accident.

“This,” we remarked as we returned the papers, “belongs apparently to the milk-and-water School of Novels.” “You are quite right,” our friend replied, “and, in its present state, it is of course utterly unsaleable in the present day: we shall find, however, that the next stage of development will remove it into the strong-minded or Matter-of-Fact School.” After dipping into various acids, he again submitted it to us: it had now become the following:—

“The evening was of the ordinary character, barometer at ‘change’: a wind was getting up in the wood, and some rain was beginning to fall; a bad look-out for the farmers. A gentleman approached along the bridle-road, carrying a stout knobbed stick in his hand, and mounted on a serviceable nag, possibly worth some £40 or so; there was a settled business-like expression on the rider’s face, and he whistled as he rode; he seemed to be hunting for rhymes in his head, and at length repeated, in a satisfied tone, the following composition:—

“Well! So my offer was no go!

She might do worse, I told her so;

She was a fool to answer ‘No.’

“However, things are as they stood;

Nor would I have her if I could,

For there are plenty more as good.”

At this moment the horse set his foot in a hole, and rolled over; his rider rose with difficulty; he had sustained several bruises, and fractured two ribs; it was some time before he forgot that unlucky day.”

We returned this with the strongest expression of admiration, and requested that it might now be developed to the highest possible degree. Our friend readily consented, and shortly presented us with the result, which he informed us belonged to the Spasmodic or German School. We perused it with indescribable sensations of surprise and delight.

“The night was wildly tempestuous—a hurricane raved through the murky forest—furious torrents of rain lashed the groaning earth. With a headlong rush—down a precipitous mountain gorge—dashed a mounted horseman armed to the teeth—his horse bounded beneath him at a mad gallop, snorting fire from its distended nostrils as it flew. The rider’s knotted brows—rolling eye-balls—and clenched teeth—expressed the intense agony of his mind—weird visions loomed upon his burning brain—while with a mad yell he poured forth the torrent of his boiling passion:--

“Firebrands and daggers! hope hath fled!

To atoms dash the doubly dead!

My brain is fire—my heart is lead!

“Her soul is flint, and what am I?

Scorch’d by her fierce, relentless eye,

Nothingness is my destiny!”

There was a moment’s pause. Horror! his path ended in fathomless abyss— * * * A rush—a flash—a crash—all was over. Three drops of blood, two teeth, and a stirrup were all that remained to tell where the wild horseman met his doom.”

The young man was now recalled to consciousness, and shown the result of the workings of his mind: he instantly fainted away.

In the present infancy of the art we forbear from further comment on this wonderful discovery; but the mind reels as it contemplates the stupendous addition thus made to the powers of science.

Our friend concluded with various minor experiments, such as working up a passage of Wordsworth into strong, sterling poetry: the same experiment was tried on a passage of Byron, at our request, but the paper came out scorched and blistered all over by the fiery epithets thus produced.

As a concluding remark: could this art be applied (we put the question in the strictest confidence)—could it, we ask, be applied to the speeches in Parliament? It may be but a delusion of our heated imagination, but we will still cling fondly to the idea, and hope against hope.

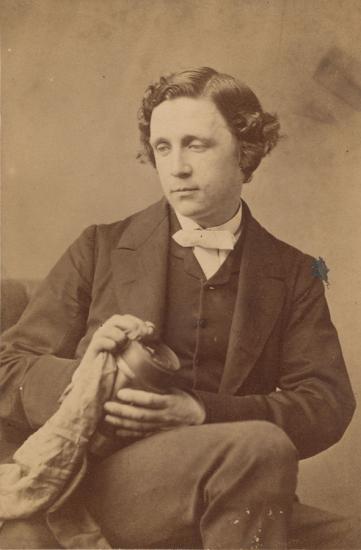

Image Caption:

O. G. Rejlander (1813—1875)

Lewis Carroll with lens

London, 28 March 1863

Carte de visite albumen print

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, AAH 220.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Carroll’s story for Mary Emma Watson

Carroll told this story to Mary Watson and her two sisters one summer’s day in 1871. Decades later, Mary fondly recalled the tale

Well, then, this story is about three little girls living in a pretty old town on the banks of the River Wey with their mother, who spent all her time thinking how she could make them happy. And they were happy, too, except that sometimes they were inclined to feel a little discontented. If you look at picture No. 1, you will see what I mean: there the children are evidently saying ‘What shall we do next?’ and their mother is wondering how she can best amuse them. But, then, too much happiness, like too much cake, is apt to disagree with people—big as well as little. They had a lovely time between lessons; there were excursions and picnics, and all sorts of doings, and the summer days used to slip away in a delightful manner.

Now among their fairy stories was one about three little pigs who, when their mother died, went into the wood and built three little houses to live in: one was built of straw, another of wood and straw, and the third of bricks. But a wicked wolf came along and being hungry thought a little pig would make a very nice dinner. So he blew the straw house down and ate up the first little pig. The next day he blew down the wooden house, though it was much more difficult, and the second little pig went the same way as his poor brother. Of course, it was soon time for another dinner, so Mr. Wolf went to the brick house and blew—and blew—and blew; but nothing happened. It was too strongly built for him to blow down, so he seated himself and thought hard; and at last he had a brilliant idea: he would go down the chimney. So he climbed on to the roof; but when the little pig heard the noise, he, too, had a brilliant idea: he lighted a fire in the grate, and put a large pot of water on to boil. And when the wolf came down the chimney he fell into the pot and was cooked.

The children thought this a lovely story—all but the part where the two little pigs were eaten. How nice it would be if they were to build three little houses to live in, and they needn’t be afraid of wolves for there weren’t any in those days. Off they went; and the eldest one built a dear little house of wood with a thatched roof—just like the second picture. The next child built hers with brick walls and wooden roof—like picture No. 3. The third—whose name, I think, was Mary—built hers with brick walls and a flat brick roof—as you see in picture No. 4, which has no chimney.

It was all very jolly and nice for a time, though I think the children began to feel a bit lonely and wish for each other’s company, especially in the evenings after tea. Now it is true that in those days there were no wolves with a fancy for little girls for dinner. But there was an old fox who lived in the wood near by, and who loved nothing better than frightening children. When he heard that three little girls had built three little houses and each was living alone he jumped for joy and started off. Very soon he came to the little wooden house with the thatched roof, slyly peeped in at the window, and saw the biggest girl sitting before the fire trying to read a book. Really she was wishing she was at home.

Mr. Fox determined to blow the house down in the proper fairy-story fashion. The next day there was a heavy gale. Filling a large can with the wind, as you see in picture No. 5, he pushed it in at the window of the biggest girl’s house. Bang it went and the house fell down like picture No. 6, just as Hartie escaped. You may depend that she ran home as fast as she could, thoroughly frightened, and determined never to go away from home again.

The old fox was delighted with the success of his plan, and the next day, having filled another can with wind, he went off to the house of the second little girl, who saw him coming and hid in the cupboard. Directly the fox placed the can of wind on the shelf, just inside the window, and off it went! But it only blew the roof off—chimney and all, as you will see in picture No. 7. However, that was enough for Ina—didn’t I say her name was Ina?—who sprang out of the cupboard, through the back door, and straight for home, while the old fox rolled on the ground with laughter. Ina soon reached home and flew into her mother’s arms vowing that she never wanted to go away again, especially alone.

But what about the youngest little girl, Mary; we must see how she got on. Mr. Fox had a good look at her house to see how he could best blow it up or down. But it was not such an easy task as the others. You will remember she had built it all of bricks, even the roof; the windows were all barred , and there was no convenient chimney or he might have tried putting a can of wind down it. He could think of nothing then; so he went home to consider what was best to be done. Early next morning he had no better plan than that of knocking at the door and, when it was opened, throwing the can of wind in. But he didn’t know Mary: she quite expected the visit and had been making plans for his reception.

You must know that Mary had built her house on a hill; and when she saw Mr. Fox coming up the hill she took her butter churn (she had a beauty in the house) and opening the door gave it a good push which sent it rolling down the hill—you can see it rolling down in picture No. 8. It went faster every moment, and when the fox saw it bounding towards him it was too late for him to get out of the way: the heavy churn went right over him and killed him.

The only thing to do now was to cook and eat him like the little pig in the story. So she fetched him up the hill, put him in a big pot on the fire and cooked him, tail and all—as you see in the last picture. As she sat down to the meal, what was her delight to see her mother coming in. Nothing could be better, and Mary soon had a place laid for mother. I suppose they soon disposed of Mr. Fox. There they are in the picture ready to begin on the dinner so kindly provided by the old schemer. Although everything ended very happily, I am quite sure Mary was glad to return home with her mother. She was welcomed by her sisters and they resumed their old happy life, enjoying it all the more because of their adventures.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Storyboard drawing for Mary Emma Watson, signed with initials “C.L.D.” and dated [Guildford, 1871]

Private collection.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Alice’s letter to her father

Nine-year-old Alice wrote this letter to her father from their country house on the Welsh coast

Penmorfa,

Landudno.

My dearest Papa.

Many many happy returns

of your birthday, the 6th of Febry That

makes you (as you were born in “William the

Conquerors” time) 797 years old. Yesterday

we had another gale it left off at 12 Edith

and I had our beds moved down into Harry’s

room, we lay on two mattresses on the floor

and were very comfortable indeed little Rho-

-da had her little cot down into Mama’s

room where Pickey and Ina slept and

Mama was in the Blue Room, altogether

we were very jolly. We shall be very glad

to see you again. We are reading “Daisy

Burns,” we like it very much have you

read it? Mama has. We went to the town

today with Mademoiselle Dué Mrs.

Bagots governess. she ran after us to try

and catch us but she could[n’t] and we had

a great bit of fun. The sun made its first

attempt to make a sunset, there has not

been any [appearance] of one before to-day

since you left. I have been trying to illu-

minate I have not anything more to tell

you as I shall be able to tell you better

by mouth which is better than letter

I remain ever

Your affectionate and loving daughter

Alice Pleasance Liddell.

Thursday evening

5th of Feb 1863.

Alice Liddell (1852–1934)

Letter to her father, Henry Liddell, signed and dated Penmorfa, Llandudno, 5 February 1863

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, MA 6348.

Photography by, Graham S Haber 2015.

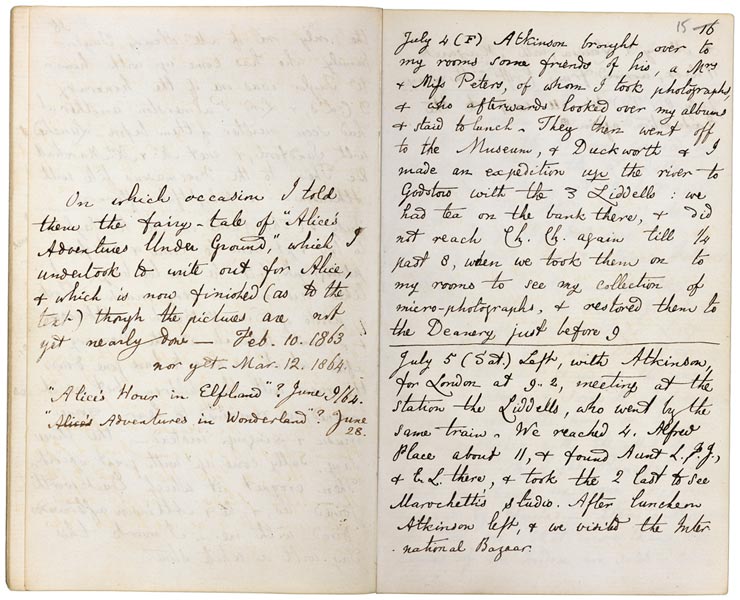

Carroll’s diary for 4 July 1862

Carroll wrote about the outing that occasioned the first telling of “Alice’s Adventures” in a characteristically brief diary entry

[Entry begins on right-hand page:]

July 4 (F) Atkinson brought over to

my rooms some friends of his, a Mrs.

& Miss Peters, of whom I took photographs,

& who afterwards looked over my albums

& staid to lunch. They then went off

to the Museum, & Duckworth & I

made an expedition up the river to

Godstow with the 3 Liddells: we

had tea on the bank there, & did

not reach Ch. Ch. Again till ¼

past 8, when we took them on to

my rooms to see my collection of

micro-photographs, & restored them to

the Deanery just before 9

----------------------------------------------------------

July 5 (Sat.) Left, with Atkinson,

for London at 9.. 2, meeting at the

station the LIddells, who went along by the

same train. We reached 4, Alfred

Place about 11, & found Aunt [Lucy, Frances],

& [Elizabeth] there, & took the 2 last to see

Marochetti’s studio. After luncheon

Atkinson left, & we visited the Inter-

-national Bazaar.

[Carroll’s addition to the July 4 entry, on the left-hand page:]

On which occasion I told

them the fairy-tale of “Alice’s

Adventures Under Ground,” which I

undertook to write out for Alice,

& which is now finished (as to the

text) though the pictures are not

yet nearly done—Feb. 10. 1863

nor yet—Mar. 12. 1864.

“Alice’s Hour in Elfland”? June 9/64.

“Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”? June 28.

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

Diary entry for 4 July 1862

© The British Library Board, Add MS 54343

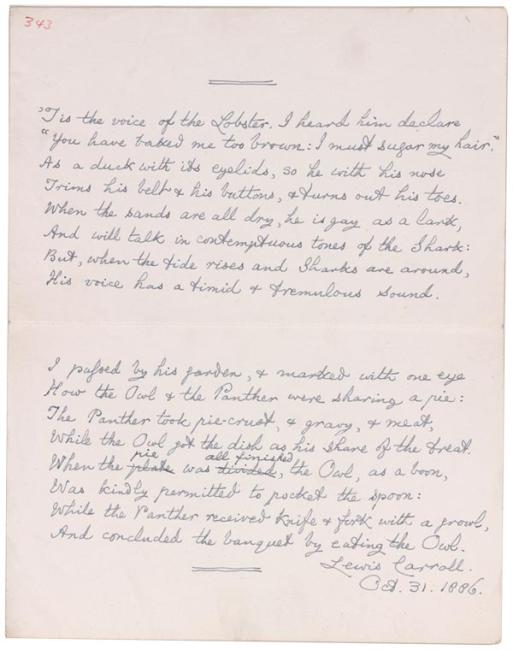

Carroll’s “’Tis the Voice of the Lobster”

Carroll wrote the second stanza of the nonsense poem in 1886 for the first theatrical adaptation of Alice

’Tis the voice of the Lobster, I heard him declare

“You have baked me too brown: I must sugar my hair.”

As a duck with its eyelids, so he with his nose

Trims his belt & his buttons, & turns out his toes.

When the sands are all dry, he is gay as a lark,

And will talk in contemptuous tones of the Shark:

But, when the tide rises and Sharks are around,

His voice has a timid & tremulous sound.

I passed by his garden, & marked with one eye

How the Owl & the Panther were sharing a pie:

The Panther took pie-crust, & gravy, & meat,

While the Owl got the dish as his share of the treat.

When the plate pie was divided all finished, the Owl , as a boon,

Was kindly permitted to pocket the spoon:

While the Panther received knife & fork with a growl,

And concluded the banquet by eating the Owl.

Lewis Carroll.

Oct. 31. 1886

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

“‘Tis the Voice of the Lobster”

Manuscript poem, signed and dated 31 October 1886

Alfred C. Berol Collection, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

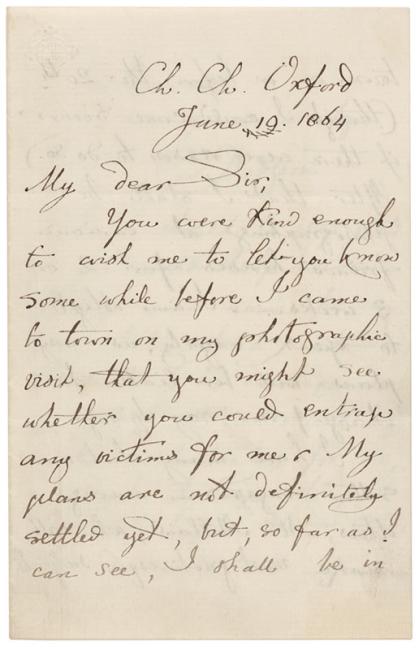

Carroll’s letter to Tom Taylor

Carroll wrote to Tom Taylor, the Victorian dramatist and editor of Punch magazine, to ask for help in “fixing on a name” for his fairy tale

Ch. Ch. Oxford

June 10. 1864

My dear Sir,

You were kind enough

to wish me to let you know

some while before I came

to town on my photographic

visit, that you might see

whether you could entrap

any victims for me. My

plans are not definitely

settled yet, but, so far as I

can see, I shall be in

town on or before the 20th

(though I could come sooner

If there were reason to do so.)

After that I shall be

photographing at various

friends' houses for 2 or

3 weeks.— I am obliged

to speak vaguely, as my

plans will be liable to

change from day to day.—

I have many children

sitters engaged—among

others, Mr. Millais', who will

make most picturesque subjects.

Believe me

Ever yours truly

C. L. Dodgson

P.S. I should be very glad

If you could help me in

fixing on a name for my

fairy-tale, which Mr.

Tenniell (in consequence

of your kind introduction)

is now illustrating for me,

& which I hope to get

published before Xmas. The

heroine spends an hour

underground, & meets various

birds, beasts & (no fairies)

endowed with speech. The

whole thing is a dream, but

that I don't want revealed

till the end. I first thought

of “Alice's Adventures

Under Ground,” but that

was pronounced too like

a lesson-book, in which

instruction about mines

would be administered in

the form of a grill: then

I took “Alice's Golden

Hour,” but that I gave

up, having a dark suspicion

that there is already

a book called “Lily's Golden Hours.”

Here are other names

I have thought of:

Alice among the { elves goblins

Alice's { hour doings adventures

in { elf-land wonderland.

Of all these I at present

prefer “Alice's Adventures

in Wonderland.” In spite of

your “morality,” I want

something sensational. Perhaps

you can suggest a name

better than any of these.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Letter to Tom Taylor, signed and dated Christ Church, Oxford, 10 June 1864

Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Carroll’s letter to Alexander Macmillan

Carroll’s earliest surviving letter to his publisher is about the binding for Alice

Ch. Ch. Oxford

Nov. 11. 1864

Dear Sir,

I have been considering

the question of the colour of

“Alice’s Adventures,” & have come

to the conclusion that bright

red will be the best—not

the best, perhaps, artistically,

but the most attractive to

childish eyes. Can this colour

be managed, with the same

smooth, bright cloth that you

have in green?

Truly yours,

CLDodgson

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Letter to Alexander Macmillan, signed and dated Christ Church, Oxford, 11 November 1864

Private Collection.

Photography by Graham S Haber 2014.

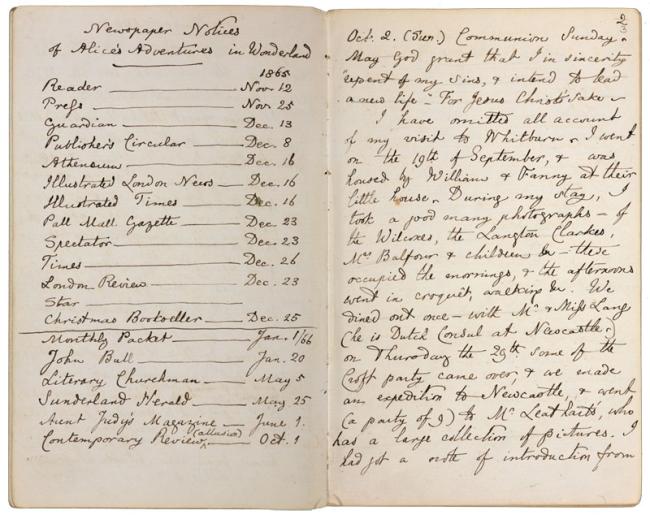

Carroll’s diary for 2 October 1866

Carroll recorded Alice’s earliest reviews on a blank page in his diary

[On left-hand page:]

Newspaper Notices

of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

-------------------------

1865

Reader----------------------------Nov. 12

Press------------------------------Nov. 25

Guardian-------------------------Dec. 13

Publisher’s Circular------------Dec. 8

Athenaeum----------------------Dec. 16

Illustrated London News------Dec. 16

Illustrated Times----------------Dec. 16

Pall Mall Gazette---------------Dec. 23

Spectator-------------------------Dec. 23

Times------------------------------Dec. 26

London Review-----------------Dec. 23

Star--------------------------------

Christmas Bookseller----------Dec. 25

_____________________________

Monthly Packet-----------------Jan. 1/66

John Bull--------------------------Jan. 20

Literary Churchman-----------May 5

Sunderland Herald------------May 25

Aunt Judy’s Magazine-------June 1

(allusion)

Contemporary Review^------Oct. 1

[On right-hand page:]

Oct. 2. (Sun.) Communion Sunday.

May God grant that I in sincerity

“repent of my sins, & intend to lead

a new life—“ For Jesus Christ’s sake—

I have omitted all account

of my visit to Whitburn. I went

on the 19th of September, & was

housed by William & Fanny at their

little house. During my stay, I

took a good many photographs—of

the Wilcoxes, the Langton Clarkes,

Mrs. Balfour & children &c.—these

occupied the mornings, & the afternoons

went in croquêt, walking &c., We

dined out once—with Mr. & Miss Lang

(he is Dutch Consul at Newcastle.)

on Thursday the 29th some of the

Croft party came over, & we made

an expedition to Newcastle, & went

(a party of 9) to Mr. Leathart’s, who

has a large collection of pictures. I

had got a note of introduction from

[Mr. Arthur Hughes, who is painting a picture of Mrs. Leatheart and the children…]

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

List of “Newspaper Notices of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” facing diary entry dated 2 October 1866

© The British Library Board, Add MS 54344

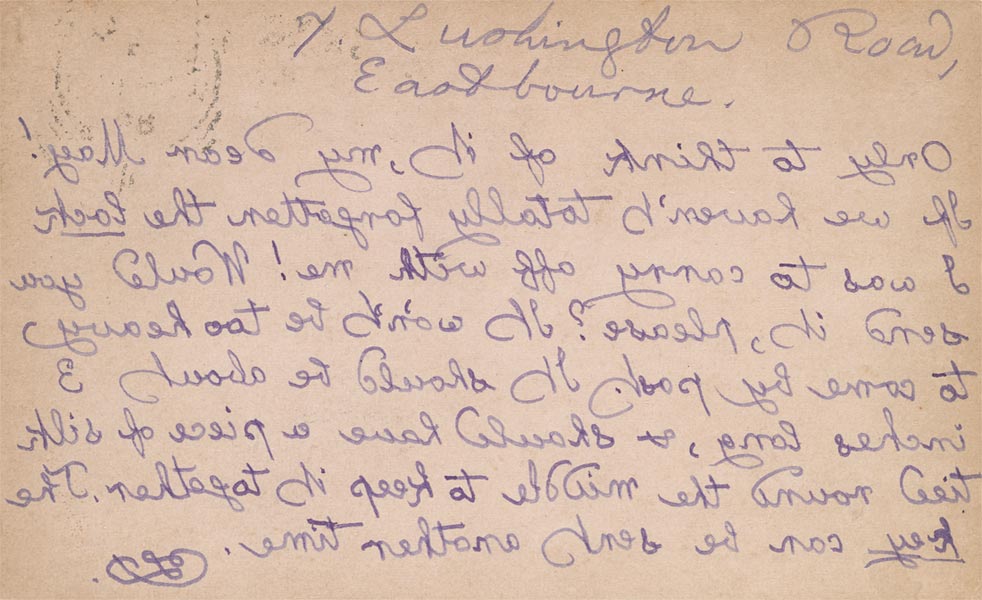

Carroll’s “Looking-Glass” postcard

Carroll playfully wrote this postcard to Mary Mileham in “looking-glass writing”

7 Lushington Road,

Eastbourne

Only to think of it, you dear Mary!

If we haven’t totally forgotten the lock

I was to carry off with me! Would you

send it, please? It wo’n’t be too heavy

to come by post. It should be about 3

inches long, & should have a piece of silk

tied round the middle to keep it together. The

key can be sent another time.

CLD.

Postcard to Mary Mileham, signed in reverse “C.L.D.” and dated Eastbourne, 14 September 1884

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015

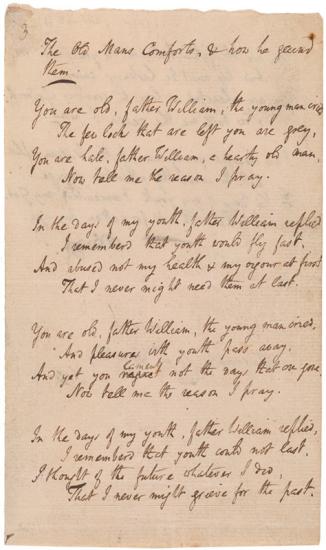

Southey’s “The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them”

Alice’s “Ballad of Father William” is a parody of the Romantic poet Robert Southey’s 1799 poem “The Old Man’s Comforts and How He Gained Them”

The Old Mans Comforts, & how he gained

them.

You are old, father William, the young man cried

The few locks that are left you are grey,

You are hale, Father William, a hearty old man,

Now tell me the reason I pray.

In the days of my youth, father William replied

I remember’d that youth would fly fast,

And abused not my health & my vigour at first

That I never might need them at last.

You are old, father William, the young man cried,

And pleasures with youth pass away,

And yet you regret lament not the days that are gone,

Now tell me the reason I pray.

In the days of my youth, father William replied,

I remembe’d that youth could not last.

I thought of the future whatever I did,

That I never might grieve for the past.

You are old, father William, the young man cried,

And life must be hastening away.

You are cheerful & love to converse upon death,

Now tell me the reason I pray.

I am cheerful young man, father Wililam replied

Let the cause thy attention engage—

In the days of my youth I remembered my God,

And He hath not forgotten my age.

S.

Image Caption:

Robert Southey (1774—1843)

The Old Man’s Comforts, and How He Gained Them

Autograph poem, signed “S” and dated ca. 1799 or later

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, MA 8622.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Tenniel’s letter to Carroll

Tenniel advised Carroll to cut the “railway scene” from the Looking-Glass manuscript

10 Portsdown Road.

April 4.

My dear Dodgson,

I should have

written sooner but I

have been a good deal

worried in various ways.

I would infinitely

rather give no opinion

as to what would be

best left out in the

book—but since you

put the question point-

blank, I am bound

to say—supposing

excision somewhere to be

absolutely necessary—

that the Railway scene

never did strike me as

being very strong, & that

I think it might be sacri-

ficed without much repining—

besides, there is no subject

down in the illustration of

it in the condensed list.

Please let me know to

what extent you have

used—or intend using—

the pruning-knife—my

great fear is that all

this indecision & revision

will interfere fatally with

the progress of the book.

In hast to claim post.

Yours sincerely

J. Tenniel

You shall have some more sizes in a few days.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Letter to Charles Dodgson, signed and dated 11 Portsdown Road, London, 4 April [1870]

Alfred C. Berol Collection, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

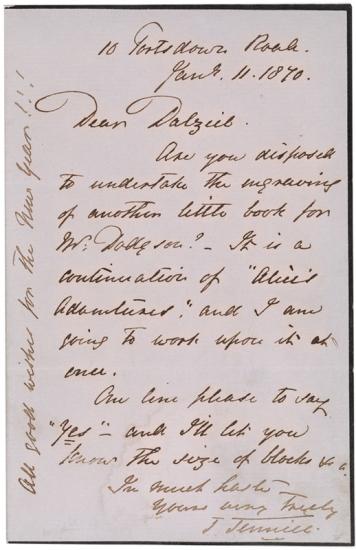

Tenniel’s letter to the Dalziel Brothers

Tenniel wrote the Dalziel brothers to ask if they would engrave the illustrations for Looking-Glass

10 Portsdown Road.

Jany. 11. 1870.

Dear Dalziel

Are you disposed

to undertake the engraving

of another little book for

Mr. Dodgson?—It is a

continuation of “Alice’s

Adventures,” and I am

going to work upon it at

once.

One line please to say

“yes”—and I’ll let you

know the size of blocks &c.

In much haste—

Yours very truly

J. Tenniel.

All good wishes for the New Year!!!

Image Caption:

John Tenniel (1820—1914)

Letter to Edward or George Dalziel, signed and dated 11 Portsdown Road, London, 11 January 1870

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Purchased on the Fellows Fund, with the special assistance of Julia P. Wightman, 1982.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

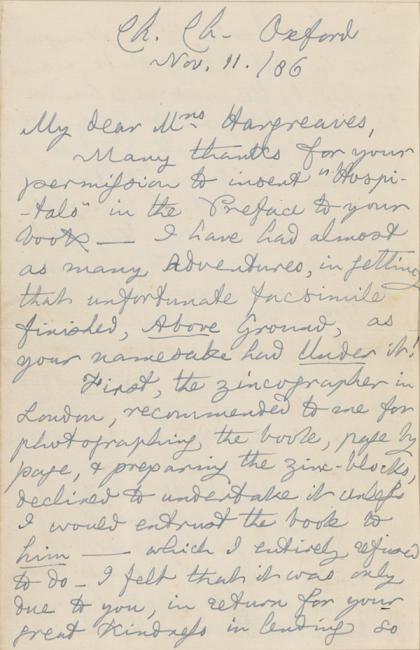

Carroll’s letter to Alice

Ch. Ch. Oxford

Nov. 11. / 86

My dear Mrs. Hargreaves,

Many thanks for your

permission to insert “Hospi-

-tals” in the Preface to your

book—I have had almost

as many Adventures, in getting

that unfortunate facsimile

finished, Above Ground, as

your namesake had Under it!

First, the zincographer in

London, recommended to me for

photographing the book, page by

page, & preparing the zinc-blocks,

declined to undertake it unless

I would entrust the book to

him—which I entirely refused

to do. I felt that it was only

due to you, in return for your

great kindness in lending so

[letter continues on back of the page:]

unique a book, to be scrupulous in not letting it be even touched by the workmen’s hands. In vain I offered to come and reside in London with the book, and to attend daily in the studio, to place it in position to be photographed, and turn over the pages required: he said that could not be done because “other author’s works were being photographed there, which must on no account be seen by the public.” I undertook not to look at anything but my own book: but it was no use: we could not come to terms.

Then Messrs. Macmillan recommended a certain Mr. Noad, an excellent photographer, but in so small a way of business that I should have to prepay him, bit by bit, for the zinc-blocks: and he was willing to come to Oxford, and do it here. So it was all done in my studio, I remaining in waiting all the time, to turn over the pages.

But I daresay I have told you so much of the story already?

Mr. Noad did a first rate set of negatives, and took them away with him to get the zinc-blocks made. These he delivered pretty regularly at first, and there seemed to be every prospect of getting the book out by Christmas 1885.

On October 18, 1885, I sent your book to Mrs. Liddell, who had told me your sisters were going to visit you and would take it with them. I trust it reached you safely?

Soon after this—I having prepaid for the whole of the zinc-blocks—the supply suddenly ceased, while 22 pages were still due, & Mr. Noad disappeared! My belief is that he was in hiding from his creditors.

We sought him in vain. So things went on for months. At one time I thought of employing a detective to find him, but was assured that “all detectives are scoundrels”—The alternative seemed to be to ask you to lend the book again, & get the missing pages re-photographed. But I was most unwilling to rob you of it again, & also afraid of the risk of loss of the book, if sent by post—for even ‘registered post’ does not seem absolutely safe—

In April he called at Macmillan’s & left 8 blocks, & again vanished into obscurity—

This left us with 14 pages (dotted up and down the book) still missing. I waited awhile longer, and then put the thing into the hands of a Solicitor, who soon found the man, but could get nothing bur promises from him. “You will never get the blocks,” said the Solicitor, “unless you frighten him by a summons before a Magistrate.” To this at last I unwillingly consented; the summons had to be taken out at Stratford-le-Bow (that is where the aggravating man is living), and this entailed 2 journeys from Eastbourne—one to get the summons (my personal presence being necessary, and the other to attend in Court with the Solicitor on the day fixed for hearing the case. The defendant didn’t appear; so the magistrate said he would take the case in his absence. Then I had the new and exciting experience of begin put into the witness=box, and sworn, and cross-examined by a rather savage Magistrate’s clerk, who seemed to think that, if he only bullied me enough, he would soon catch me out in a falsehood! I had to give the Magistrate a little lecture on photo-zincograhy, and the poor man declared the case so complicated he must adjourn it for another week. But this time, in order to secure the presence of our slippery defendant, he issued a warrant for his apprehension, and the constable had orders to take him into custody and lodge him in prison, the night before the day when the case was to come on. The news of this effectually frightened him, and he delivered up the 14 negatives (he hadn’t done the blocks) before the fatal day arrived. I was rejoiced to get them, even though it entailed the paying a 2nd time for getting the 14 blocks done, and withdrew the action.

The 14 blocks were quickly done and put into the printer’s hands; and all is going on smoothly at last: and I quite hope to have the book completed, and to be able to send you a very special copy (bound in white vellum, unless you would prefer some other style of binding) by the end of the month.

Believe me always

Sincerely yours,

C. L. Dodgson

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Letter to Alice Liddell Hargreaves, signed and dated Christ Church, Oxford, 11 November 1886

Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

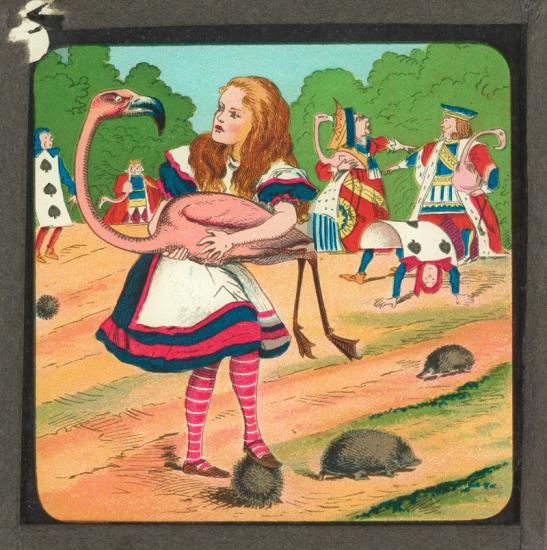

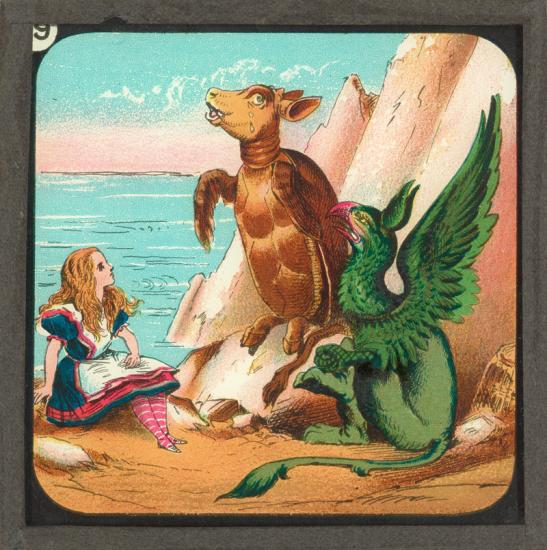

Alice in Wonderland magic lantern slides

The prompts that accompanied these magic lantern slides borrow heavily from Lewis Carroll’s text, just as the slides closely echo Tenniel’s original designs

“Off with their heads!” cried the Queen, when she found out what the three gardeners had been doing, but Alice saved them by putting them into a large flower-pot that stood near, and where the soldiers could not see them. “Can you play croquet?” the Queen asked Alice. Alice replied, “Yes.” “Come on, then,” said the Queen, and the procession moved on to the croquet ground. It was the most curious game that Alice had ever played: the ground was all ridges and furrows, the balls were live hedge-hogs, the mallets live flamingos, and the soldiers doubled themselves up and stood upon their hands and feet to make the arches. Alice found a great difficulty in managing her flamingo; it would twist itself round and look up in her face, with such a puzzled expression, that she could not help laughing, whilst the hedge-hogs crawled away just when she wanted to hit them, and the doubled-up soldiers were always getting up and walking off to other parts of the ground. It was a very difficult game indeed. Presently she noticed a curious appearance in the air. It puzzled her at first, but soon she made it out to be a grin, and she said to herself, “It’s the Cheshire Cat: now I shall have somebody to talk to.”

Image Caption:

W. Butcher & Sons

Alice in Wonderland

Magic lantern slides issued in the Primus junior lecturers' series, number 778d

London, 1905-1908

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PML 352354.1-7.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Magic lantern slide 2

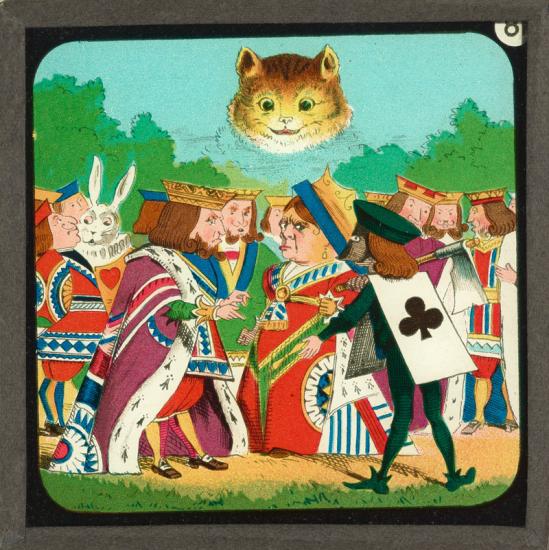

The prompts that accompanied these magic lantern slides borrow heavily from Lewis Carroll’s text, just as the slides closely echo Tenniel’s original designs

Only the Cat’s head appeared; it seemed to think that was sufficient. “Who are you talking to?” said the King, coming up to Alice. “It’s a friend of mine—a Cheshire Cat,” said Alice, “Allow me to introduce it.” “I don’t like the look of it at all,” said the King, “It must be removed,” and he called to the Queen, “My Dear! I wish you would have this Cat removed!” “Off with his head!” answered the Queen. But here a difficulty arose, and the question was hotly argued. The executioner said that you couldn’t cut off a head unless there was a body to cut it off from; the King said that anything that had a head could be beheaded; and the Queen said that if something wasn’t done about it in less than no time, she’d have everybody executed all around. The Cat settled the question by quietly fading away, and the players went back to their game. Presently the Queen asked Alice, “Have you seen the Mock Turtle yet?” “No,” said Alice, “I don’t even know what a Mock Turtle is.” “It’s a thing that Mock Turtle Soup is made from,” said the Queen; “Come on and he shall tell you his history.”

Image Caption:

W. Butcher & Sons

Alice in Wonderland

Magic lantern slides issued in the Primus junior lecturers' series, number 778d

London, 1905-1908

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PML 352354.1-7.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

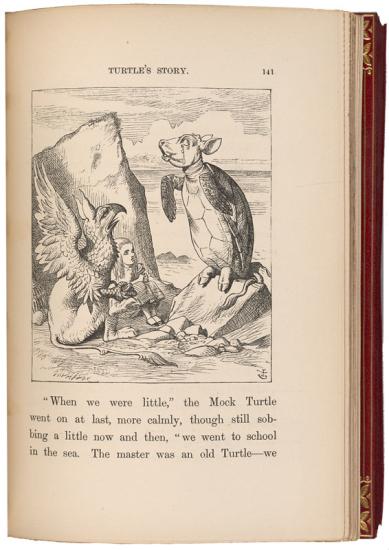

Magic lantern slide 3

The prompts that accompanied these magic lantern slides borrow heavily from Lewis Carroll’s text, just as the slides closely echo Tenniel’s original designs

Very soon they came upon a Gryphon, and the Queen put Alice in his charge, saying she had to go back

and see after some executions. “What fun!” said the Gryphon: “What is the fun?” said Alice. “Why, she,”

said the Gryphon. “It’s all her fancy, that: they never executes nobody, you know. Come on!” So they

came to the Mock Turtle, sitting sad and lonely on a ledge of rock, and sighing as if his heart would

break. “This here young lady,” said the Gryphon, “she wants for to know your history, she do.” With

many sobs and eyes full of tears, the Mock Turtle told his story. “Once,” he began, “I was a real Turtle.

When we were little we went to school in the sea. The master was and old Turtle; we used to call him

Tortoise.” “Why did you call him Tortoise, if he wasn’t one?” “We called him Tortoise because he taught

us. We had the best of educations. I took the regular courses—couldn’t afford extras. There was Reeling

and Writhing to begin with, and then the different branches of Arithmetic: Ambition, Distraction,

Uglification and Derision. Never heard of Uglification? You know what to beautify is, I suppose?” “Yes,”

said Alice, “it means to make anything prettier.” Well, then, if you don’t know what to uglify is you must

be a simpleton.” “What else had you to learn?” asked Alice. “Well, there was Mystery, ancient and

modern, with Seaography, then Drawling: the Drawling Master was an old Conger Eel, that used to come

once a week; he taught us Drawling, Sketching and Fainting in Coils.” “Tell her about the games,” said

the Gryphon. The Mock Turtle sighed deeply, and with difficulty repressed his sobs. “You may not have

lived much under the sea,” he went on, “and perhaps were never even introduced to a Lobster, so you

can have no idea what a delightful thing a Lobster Quadrille is.”

Image Caption:

W. Butcher & Sons

Alice in Wonderland

Magic lantern slides issued in the Primus junior lecturers' series, number 778d

London, 1905-1908

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PML 352354.1-7.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

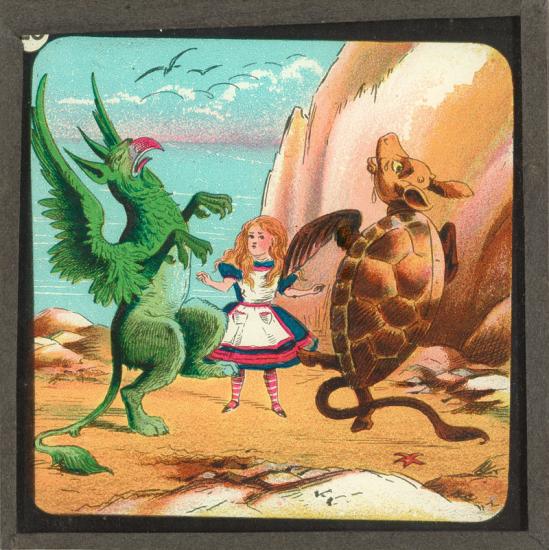

Magic lantern slide 4

The prompts that accompanied these magic lantern slides borrow heavily from Lewis Carroll’s text, just as the slides closely echo Tenniel’s original designs

“No, indeed,” said Alice. “What sort of dance is it?” “Why,” said the Gryphon, “you first form into a line

along the sea shore.” “Two lines!” cried the Mock Turtle, “Seals, Turtles and so on, then, when you’ve

cleared the jelly-fish out of the way, you advance twice.” “Each with a Lobster as a partner,” cried the

Gryphon. “Of course,” the Mock Turtle said. “Advance twice, set to partners, change Lobsters, and retire

in same order,” continued the Gryphon. “Then, you know,” the Mock Turtle went on, “you throw the—“

“The Lobsters!” shouted the Gryphon, with a bound into the air—“as far out to sea as you can—“ “Swim

after them,” screamed the Gryphon. “Turn a somersault in the sea,” cried the Mock Turtle, capering

wildly about. “Change Lobsters again,” yelled the Gryphon. “Back to land again, and that’s all in the first

figure,” said the Mock Turtle. “Would you like to see a little of it?” “Very much, indeed.” said Alice. So

they began solemnly dancing round and round Alice, singing as they went, and waving their fore paws to

mark the time. Then they had more talk, and a song about “Turtle Soup,” which was interrupted by a cry

in the distance.

Image Caption:

W. Butcher & Sons

Alice in Wonderland

Magic lantern slides issued in the Primus junior lecturers' series, number 778d

London, 1905-1908

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PML 352354.1-7.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

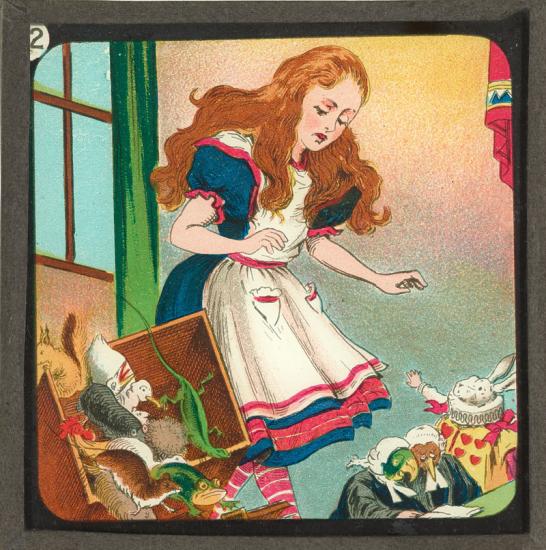

Magic lantern slide 5

The prompts that accompanied these magic lantern slides borrow heavily from Lewis Carroll’s text, just as the slides closely echo Tenniel’s original designs

“The trial’s beginning” The King and Queen were seated on their throne when they arrived, with a great

crowed assembled about them … Alice for some time had been feeling a very curious sensation, which

puzzled her a good deal until she made out what it was—she was growing larger again. Quite forgetting

this in her surprise at hearing the White Rabbit call on “Alice” as the next witness, she jumped up and

tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the Jurymen on the heads of the crowd

below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of gold-fish she had

accidentally upset the week before. “Oh, I beg your pardon!” she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay,

and began picking them up again as quickly as she could. “The trial cannot proceed until all the Jurymen

are back in their proper places,” said the King. Alice found she had put the Lizard in head downwards,

but she soon put that to right.

Image Caption:

W. Butcher & Sons

Alice in Wonderland

Magic lantern slides issued in the Primus junior lecturers' series, number 778d

London, 1905-1908

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PML 352354.1-7.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Magic lantern slide 6

The prompts that accompanied these magic lantern slides borrow heavily from Lewis Carroll’s text, just as the slides closely echo Tenniel’s original designs

The King turned to the Jury: “Consider your verdict,” he said. “No, No!” said the Queen, “sentence first,

verdict afterwards.” “Stuff and nonsense!” said Alice loudly. “Off with her head!” shouted the Queen.

“Who cares for you, said Alice, you’re nothing but a pack of cards!” … And then the whole pack rose up

into the air, and came flying down upon her. She gave a little scream and tried to beat them off, and

then found herself lying on the bank with her head in her sister’s lap, whilst some dead leaves fluttered

down from the trees upon her face. “Oh, I’ve had such a curious dream!” said Alice, and she told her

sister of her strange adventures in Wonderland.

Image Caption:

W. Butcher & Sons

Alice in Wonderland

Magic lantern slides issued in the Primus junior lecturers' series, number 778d

London, 1905-1908

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PML 352354.1-7.

Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

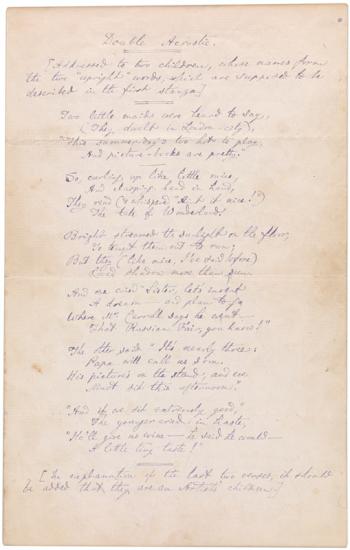

Carroll’s double acrostic poem

To solve this double acrostic, a clue must be puzzled out of each stanza (except the first). When stacked vertically, the first and last letters of the words spell out the recipients names. See below for the solution.

Double Acrostic

[Addressed to two children, whose names form

the two “upright” words, which are supposed to be

described in the first stanza.]

-----

Two little maids were heard to say,

(They dwelt in London-city),

“This summer-day’s too hot to play,

And picture-books are pretty.”

-----

So, curling up like little mice,

And clasping hand in hand,

They read (& whispered “Aint it nice!”)

The tale of Wonderland.

Bright streamed the sunlight on the floor,

To tempt them out to run;

But they (like mice, I’ve said before)

Loved shadow more than sun.

And one cried “Sister, let’s invent

A dream—and plan to go

Where Mr. Carroll says he went—

That Russian Fair, you know!”

The other said “It’s nearly three:

Papa will call us soon.

His pictures on the stand, and we

Must sit this afternoon.”

“And if we sit extremely good,”

The younger cried in haste,

“He’ll give us wine—he said he would—

A little tiny taste!”

-----

[In explanation of the last two verses, it should

Be added that they are an Artists’ children.]

The poem is addressed to Agnes and Emily Hughes, the daughters of Pre-Raphaelite painter Arthur Hughes. The solution to the double acrostic is:

A lic E

G loo M

N ijn I*

E ase L

S herr Y

* “Nijni” is a reference to the Fair of Nijni-Novgorod. Carroll visited Russia in 1867.

Image Caption:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

Double acrostic poem, ca. 1871-1891

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, MA 6381. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Picturing Wonderland

John Tenniel’s illustrations captured the essence of Wonderland. The artist drew inspiration from Carroll’s drawings but elaborated on the author’s intentions and made the characters and their interactions vibrant and magical. In turn, Carroll’s exacting vision for the overall design of the book and the precise placement of the illustrations created a dynamic relationship between text and image. Their collaboration led to the iconic and recognizable characters that live in our imaginations today. Select a character to look closely at the development of the well-known illustrations from Carroll’s earliest sketches.

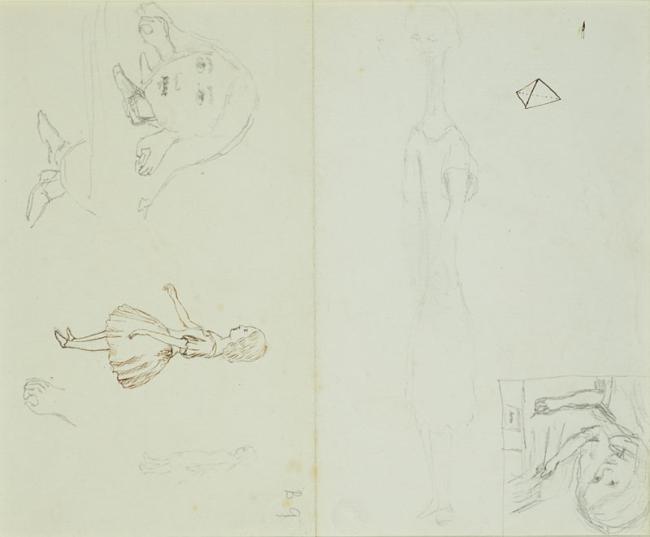

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the White Rabbit Preparatory drawing (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

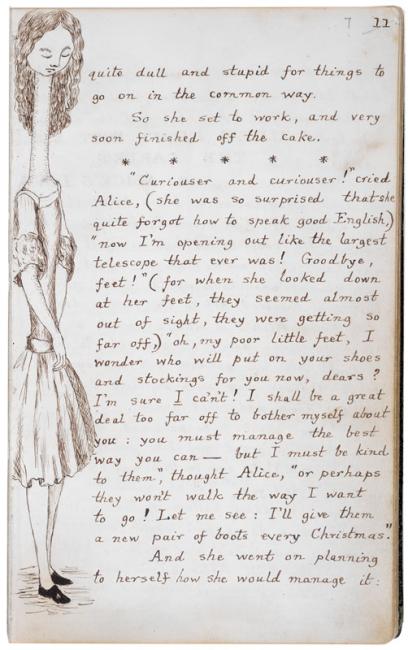

Alice

From Carroll’s a lightly penciled sketch to Tenniel’s bold Curiouser and curiouser!

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll’s earliest attempt to depict Alice grown suddenly tall is this very lightly penciled sketch on the back of a sheet of writing paper. Although her features are unfinished, the general outline shows Alice clasping her hands and looking towards her now-distant feet.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketch of Alice

Preparatory drawing (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

Carroll refined and reversed his sketch of Alice so that she would appear facing outward from the narrow margin of the original manuscript. The details of her hair and dress have been filled in, but she retains her initial demure expression.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s preparatory sketch

Tenniel keeps Carrol’s general idea, but shows us Alice’s shock at “opening up like a telescope.” Alice is no longer the quiet-looking figure of the manuscript, and confronts the change head on.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Curiouser and curiouser!

Preparatory drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

Private Collection, Photo © Christie’s Photo / Bridgeman Images

Tenniel’s final drawing

In Tenniel’s final drawing, Alice’s figure is stretched a little further and her expression is refined. A larger, unfinished study of Alice’s head partially appears in the right margin.

Image credit:

John Tenniel (1832—1914)

Curiouser and curiouser!

Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Gale, 1982.11:2.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Tenniel’s color version for The Nursery “Alice”

For the enlarged and color-printed version, Tenniel gives Alice a blue hair bow and adds ruffles to her apron. The original proof, printed by Edmund Evans, is on the right. The final version, reflecting the artist’s corrections, is on the left.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Curiouser and curiouser!

Revised color proof bound in Lewis Carroll’s The Nursery “Alice” (London: Macmillan and Co., [1889])

Private Collection. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

The White Rabbit

From Carroll’s copy of a real bunny to Tenniel’s scurrying figure

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll’s earliest drawings filled sheets of letter-writing paper. Here, he begins with a sketch of a real rabbit, which evolves over the first page into a fully anthropomorphized form. (A study of Alice in profile appears upside-down on the left.) On the second page, Carroll begins working out Alice’s first meeting with the White Rabbit.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the White Rabbit

Preparatory drawings (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

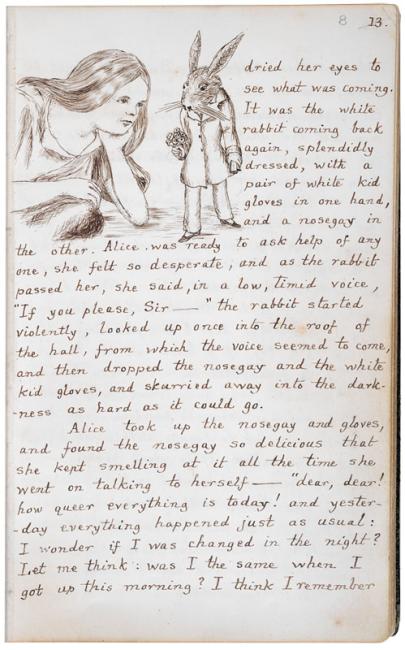

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

In Carroll’s finished illustration, the White Rabbit is essentially a human figure that has donned a full suit. Carroll depicts the exact moment just before Alice’s encounter with the White Rabbit, when she leans down for her first conversation in Wonderland.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s final drawing

Tenniel’s original drawing—which he later hand colored, presumably at the request of a collector—shifts the emphasis to the moment after Alice first speaks to the White Rabbit, and shows the startled creature, now more rabbit-like and no longer in a full suit, scurrying away.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The Rabbit Scurried Away into the Darkness

Final drawing (watercolor over graphite on paper), 1864-1865

Private Collection, Photo © Christie's Photo / Bridgeman Images

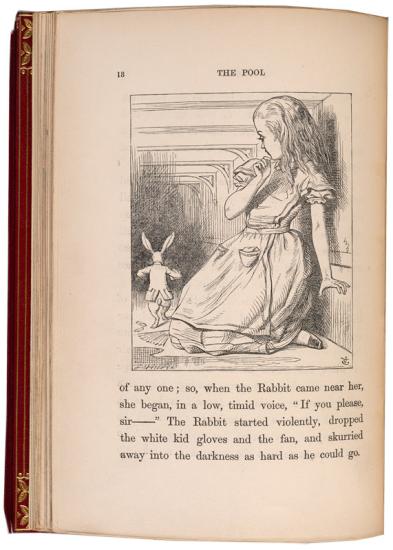

The first edition

Carroll oversaw every aspect of the design for Alice. He selected the scenes for Tenniel to illustrate and ordered the precise size (down to eighths of an inch) and placement of each picture in the book. Closely attuned to the relationship between word and image, the text below this illustration also functions as a caption.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

Tenniel’s later drawing

In the decades following the book’s immediate success, Tenniel was frequently requested to make drawings of his own illustrations for collectors. This fine example was commissioned some time after the book appeared in 1865.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The Rabbit Scurried Away into the Darkness

Post-publication drawing (graphite on paper), 1865 or later

Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

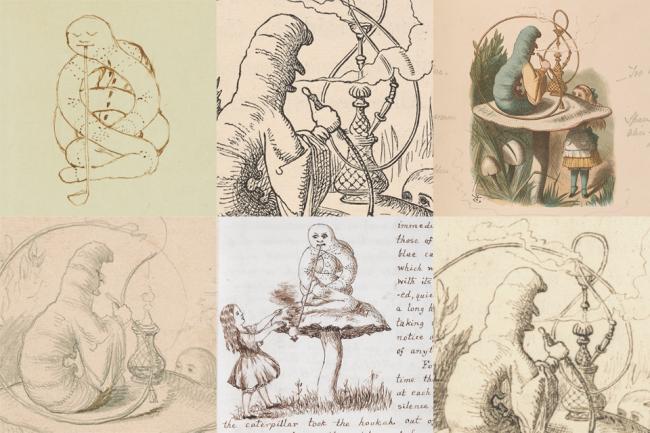

The Blue Caterpillar

From Carroll’s direct portrait to Tenniel’s enigmatic over-the-shoulder scene

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll had difficulty depicting the Blue Caterpillar. Completely wrapped up on itself, the creature is somehow limbless and must rest the hookah awkwardly on the mushroom. The depiction on the right, in brown ink, is a later trial.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the Blue Caterpillar

Drawing (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

Carroll’s finished drawing in the original manuscript refines the figures and adjusts the scale of the illustration. The straightforward depiction shows the Alice and the Blue Caterpillar languidly staring at each other in the moments before their memorable conversation.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s final drawing

For Alice’s encounter with the Blue Caterpillar, Tenniel radically alters the visual perspective from Carroll’s drawing the manuscript. Tenniel also subtly shifts the moment depicted, showing the Blue Caterpillar removing the hookah to begin the unencouraging start to their conversation: “Who are you?”

Image credit:

John Tenniel (1832—1914)

The Blue Caterpillar

Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Gale, 1982.11:3.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Dalziel’s copy

George and Edward Dalziel—the finest wood engravers of the day—were commissioned for Alice. They made these pen-and-ink copies of Tenniel’s designs probably after printing the first proofs of the illustrations.

George Dalziel (1815–1902) or Edward Dalziel (1817–1905)

After John Tenniel’s The Blue Caterpillar

Drawing (pen-and-ink on paper), 1865

The Newberry Library, Chicago. Call # Case 4A. 878

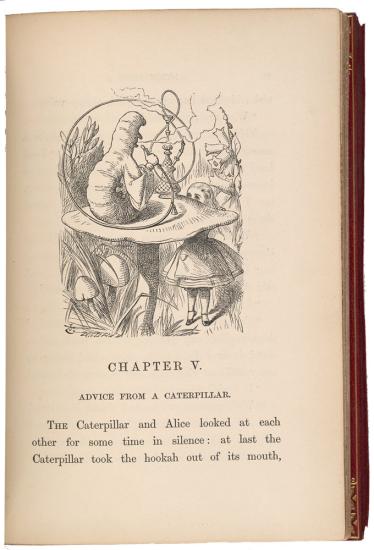

The first edition

Ever attuned to the relationship between text and image, Carroll decided to make this illustration fill up more than half of the page so that the chapter opening—which describes exactly the moment that is illustrated—could be read as a caption.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

Tenniel’s color version for The Nursery “Alice”

Tenniel worked with Edmund Evans for the first version printed in color. In the initial proof (right), the colors were generally too dark and over-saturated. Tenniel’s notes around the proof call for specific changes, reflected in the version on the left.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The Blue Caterpillar

Revised color proof bound in Lewis Carroll’s The Nursery “Alice” (London: Macmillan and Co., [1889])

Private Collection. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

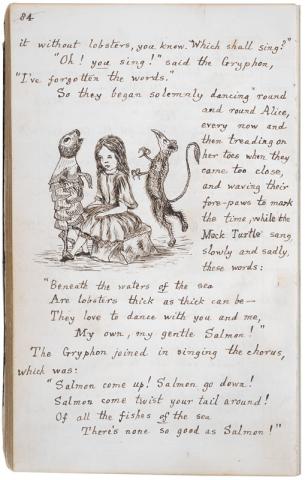

The Mock Turtle

From Carroll’s armored creature to Tenniel’s perfect pun

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll’s earliest sketches (above) of the Mock Turtle show a creature with faceted armature that looks very little like a turtle. His depiction of the Gryphon is likely based on a finished drawing by his brother, Wilfred (below).

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the Mock Turtle and Gryphon

Drawing (pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Wilfred Dodgson (1838–1914)

GryphonDrawing (pen-and-ink on paper), ca. 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

For his final drawings in the manuscript, Carroll refined his depiction of the Mock Turtle and gave him the furry head of a calf, picking up on his own pun about mock turtle soup.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

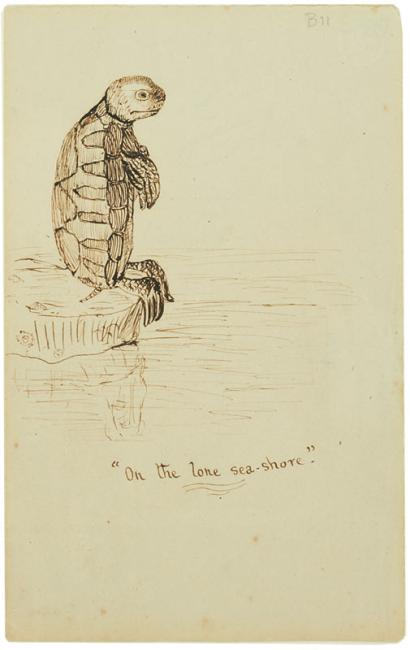

Carroll’s presentation drawing

Carroll typically used pencil for his earliest sketches; this later pen-and-ink drawing shows his most refined depiction of the Mock Turtle. Captioned “On the lone sea-shore” it does not depict a specific scene in the manuscript but may have been intended as a gift.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

“On the lone sea-shore”

Drawing (pen-and-ink on paper), ca. 1862-1865

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

The first edition

The Mock Turtle sobs constantly throughout his story (indeed, it has trouble pausing its weeping long enough to begin). Tenniel follows the text, and shows large tears streaming down the character’s face.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

Tenniel’s color version for The Nursery “Alice”

In the color-printed version, the Mock Turtle’s companion the Gryphon becomes vibrantly red and green, a detail not described in the text.

Image credit:

John Tenniel (1820—1914)

Gryphon and Mock Turtle Dance Round Alice

Hand-colored proof, 1885

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, 2005.202.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Alice in Bumbleland

Tenniel regularly mined his own work for parody in the pages of Punch. In this cartoon, Alice becomes the conservative politician Arthur Balfour bumbling through a reading of the London Government Bill. Alice retains her own features here, but in the published version, her face becomes lined, and she squints at the paper through a pair of pince-nez.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Alice in Bumbleland

Drawing (watercolor over graphite on paper), ca. 1899

Private Collection. Photography by Graham S. Haber 2015.

The White Rabbit as the Herald

From Carroll’s anonymous robes to Tenniel’s court garb

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

In one of the last scenes in the manuscript (and published book), the White Rabbit discards his pocket watch and waistcoat and takes on the role of the Herald at the trial of the stolen tarts.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s final drawing

In the original manuscript, Carroll’s version of the White Rabbit as the Herald is clothed in robes with designs reminiscent of a generic playing card; Tenniel refines the outfit to place the Rabbit clearly in the court of the Queen of Hearts.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The White Rabbit as the Herald

Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

Houghton Library, Harvard University. MS Eng 718.6 (5). Gift of Mrs. Harcourt Amory, 1927

Woodblock proofs

When the Dalziel brothers engraved Tenniel’s original design, they mistakenly cast the Rabbit’s gaze ahead. After printing the first proof (above), they spotted the error and recast his gaze askance as seen in the second proof (below).

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The White Rabbit as the Herald

First and second state woodblock proofs, 1865

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The first edition

The published version is from the corrected woodblock. Carroll carefully designed this page so that the Rabbit’s announcement appears as a caption to Tenniel’s illustration of the same.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

The Sound of Wonderland

Alice and her companions—or sometimes just the very subliminal notion of Wonderland—have stirred artists and musicians alike for the past 150 years. Listen to a selection of Alice-inspired music here

Charles Marriott (1831–1889)

The Wonderland Quadrilles

Illustrations by Alfred Concanen, after John Tenniel’s designs London: Robert Cocks & Co., [1874]

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, PMM 266. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

Alice on the Silver Screen

Alice in Wonderland (1903)

Alice was first adapted for the screen in 1903—only five years after Carroll’s death and when the film industry was still in its infancy. The film is preserved in just one badly damaged print. Originally about twelve minutes (800 feet), it was the longest film yet produced in Britain and a big production for the day. It is seemingly disjointed and wildly episodic, based only loosely on the original story, but this is partially because the individual scenes were shown interspersed with other similarly short films: several tableaux (or “actualities”) and narrative shorts would be compiled into a longer program by individual cinemas.

The directors Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stowe attempted to faithfully reproduce Tenniel’s illustrations in the film and created elaborate costumes and set designs. They also experimented with inventive special effects, to show Alice growing and shrinking and the appearance and disappearance of the Cheshire-Cat.

In the first years of the twentieth century, Hepworth’s studio was producing around one hundred films a year. Alice in Wonderland was shot on a small outdoor stage and at a nearby estate, and the actors were culled from the studio’s staff: Mabel Clark (the studio’s unofficial secretary) played Alice; Hepworth’s wife took the roles of the White Rabbit and the Queen; and Hepworth himself was the Frog Footman.

Hepworth spent his childhood assisting his father with Magic Lantern performances. He began making films in 1898 and published Animated Photography, the first handbook on film. By 1910, he was experimenting with was experimenting with ways to add sound to film, but Alice in Wonderland would have been screened with live accompaniment.

Alice in Wonderland (1915)

One of the earliest American adaptations of Alice is this 1915 production directed by W. W. Young. The film is nearly an hour long, and it too features elaborate costumes and set designs that strive to mimic Tenniel’s original designs in the book. The title character is played by Viola Savoy, who was primarily a stage actress: she was involved as many as 125 plays, but Alice is one of only two films that she acted in.

Alice in Wonderland (1931)

The first Alice film with synchronized sound (or “talkie”) was released in September 1931. The low- budget production was shot in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Although the American actors struggled with British accents, the film is one of the most faithful adaptations of the tale. It was produced in advance of the 1932 centenary of Lewis Carroll’s birth as an education aid and was not successful at the box office.