Picturing Wonderland

John Tenniel’s illustrations captured the essence of Wonderland. The artist drew inspiration from Carroll’s drawings but elaborated on the author’s intentions and made the characters and their interactions vibrant and magical. In turn, Carroll’s exacting vision for the overall design of the book and the precise placement of the illustrations created a dynamic relationship between text and image. Their collaboration led to the iconic and recognizable characters that live in our imaginations today. Select a character to look closely at the development of the well-known illustrations from Carroll’s earliest sketches.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the White Rabbit Preparatory drawing (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Alice

From Carroll’s a lightly penciled sketch to Tenniel’s bold Curiouser and curiouser!

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll’s earliest attempt to depict Alice grown suddenly tall is this very lightly penciled sketch on the back of a sheet of writing paper. Although her features are unfinished, the general outline shows Alice clasping her hands and looking towards her now-distant feet.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketch of Alice

Preparatory drawing (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

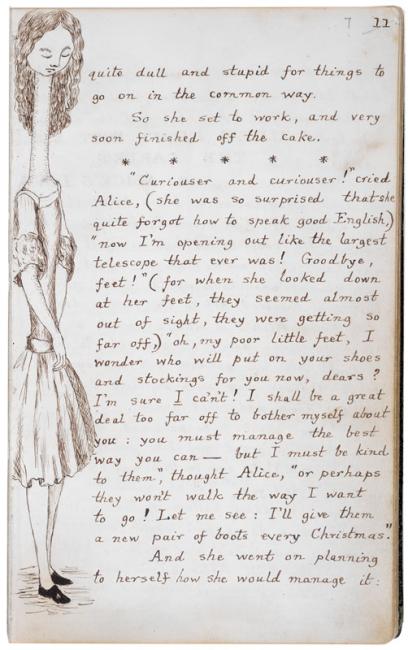

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

Carroll refined and reversed his sketch of Alice so that she would appear facing outward from the narrow margin of the original manuscript. The details of her hair and dress have been filled in, but she retains her initial demure expression.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s preparatory sketch

Tenniel keeps Carrol’s general idea, but shows us Alice’s shock at “opening up like a telescope.” Alice is no longer the quiet-looking figure of the manuscript, and confronts the change head on.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Curiouser and curiouser!

Preparatory drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

Private Collection, Photo © Christie’s Photo / Bridgeman Images

Tenniel’s final drawing

In Tenniel’s final drawing, Alice’s figure is stretched a little further and her expression is refined. A larger, unfinished study of Alice’s head partially appears in the right margin.

Image credit:

John Tenniel (1832—1914)

Curiouser and curiouser!

Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Gale, 1982.11:2.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Tenniel’s color version for The Nursery “Alice”

For the enlarged and color-printed version, Tenniel gives Alice a blue hair bow and adds ruffles to her apron. The original proof, printed by Edmund Evans, is on the right. The final version, reflecting the artist’s corrections, is on the left.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Curiouser and curiouser!

Revised color proof bound in Lewis Carroll’s The Nursery “Alice” (London: Macmillan and Co., [1889])

Private Collection. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

The White Rabbit

From Carroll’s copy of a real bunny to Tenniel’s scurrying figure

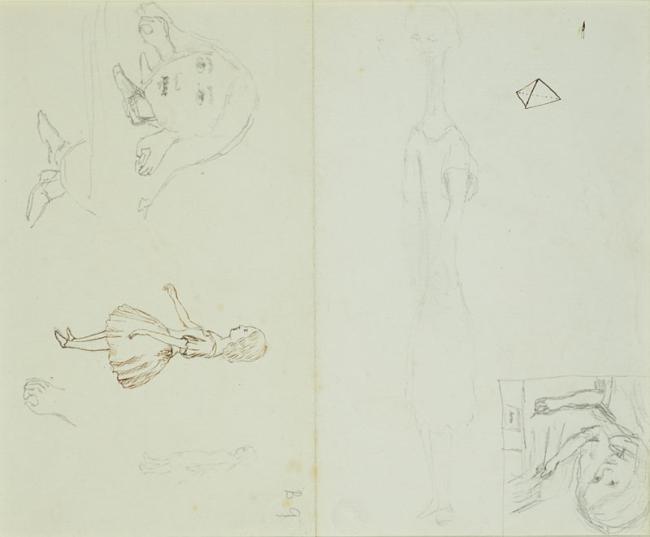

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll’s earliest drawings filled sheets of letter-writing paper. Here, he begins with a sketch of a real rabbit, which evolves over the first page into a fully anthropomorphized form. (A study of Alice in profile appears upside-down on the left.) On the second page, Carroll begins working out Alice’s first meeting with the White Rabbit.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the White Rabbit

Preparatory drawings (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

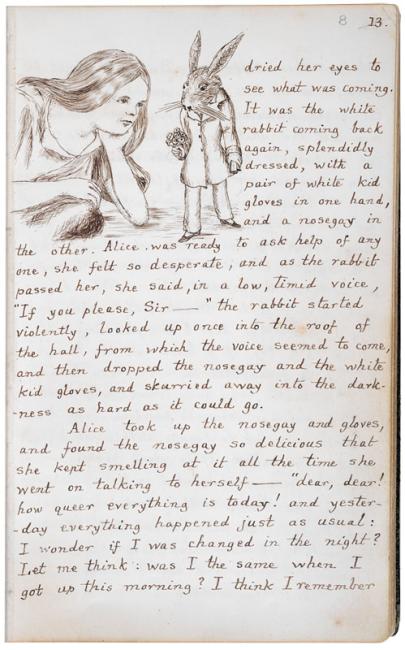

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

In Carroll’s finished illustration, the White Rabbit is essentially a human figure that has donned a full suit. Carroll depicts the exact moment just before Alice’s encounter with the White Rabbit, when she leans down for her first conversation in Wonderland.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s final drawing

Tenniel’s original drawing—which he later hand colored, presumably at the request of a collector—shifts the emphasis to the moment after Alice first speaks to the White Rabbit, and shows the startled creature, now more rabbit-like and no longer in a full suit, scurrying away.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The Rabbit Scurried Away into the Darkness

Final drawing (watercolor over graphite on paper), 1864-1865

Private Collection, Photo © Christie's Photo / Bridgeman Images

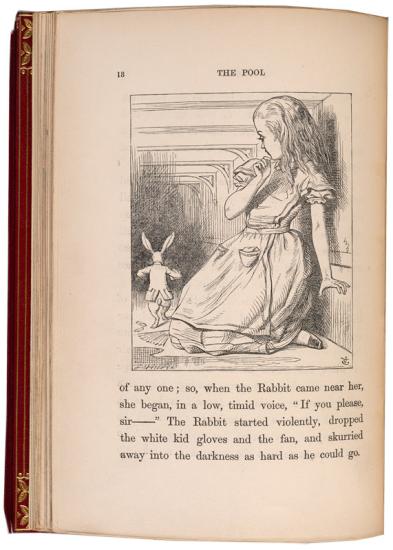

The first edition

Carroll oversaw every aspect of the design for Alice. He selected the scenes for Tenniel to illustrate and ordered the precise size (down to eighths of an inch) and placement of each picture in the book. Closely attuned to the relationship between word and image, the text below this illustration also functions as a caption.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

Tenniel’s later drawing

In the decades following the book’s immediate success, Tenniel was frequently requested to make drawings of his own illustrations for collectors. This fine example was commissioned some time after the book appeared in 1865.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The Rabbit Scurried Away into the Darkness

Post-publication drawing (graphite on paper), 1865 or later

Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

The Blue Caterpillar

From Carroll’s direct portrait to Tenniel’s enigmatic over-the-shoulder scene

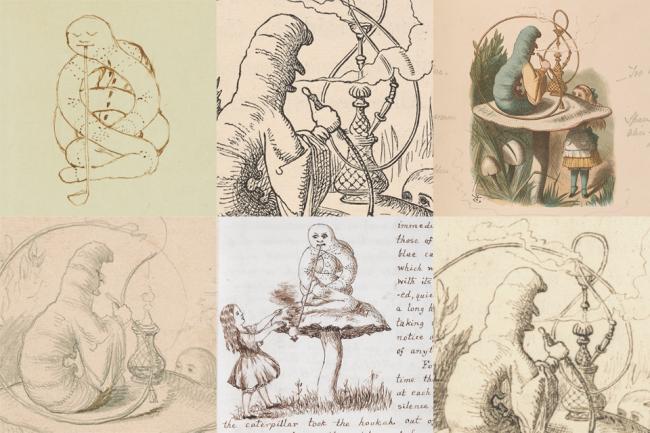

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll had difficulty depicting the Blue Caterpillar. Completely wrapped up on itself, the creature is somehow limbless and must rest the hookah awkwardly on the mushroom. The depiction on the right, in brown ink, is a later trial.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the Blue Caterpillar

Drawing (graphite and pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

Carroll’s finished drawing in the original manuscript refines the figures and adjusts the scale of the illustration. The straightforward depiction shows the Alice and the Blue Caterpillar languidly staring at each other in the moments before their memorable conversation.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s final drawing

For Alice’s encounter with the Blue Caterpillar, Tenniel radically alters the visual perspective from Carroll’s drawing the manuscript. Tenniel also subtly shifts the moment depicted, showing the Blue Caterpillar removing the hookah to begin the unencouraging start to their conversation: “Who are you?”

Image credit:

John Tenniel (1832—1914)

The Blue Caterpillar

Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Gale, 1982.11:3.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Dalziel’s copy

George and Edward Dalziel—the finest wood engravers of the day—were commissioned for Alice. They made these pen-and-ink copies of Tenniel’s designs probably after printing the first proofs of the illustrations.

George Dalziel (1815–1902) or Edward Dalziel (1817–1905)

After John Tenniel’s The Blue Caterpillar

Drawing (pen-and-ink on paper), 1865

The Newberry Library, Chicago. Call # Case 4A. 878

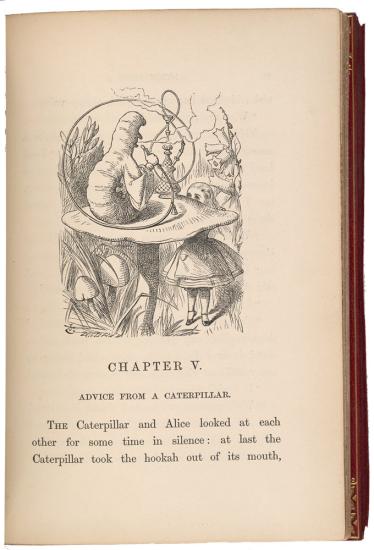

The first edition

Ever attuned to the relationship between text and image, Carroll decided to make this illustration fill up more than half of the page so that the chapter opening—which describes exactly the moment that is illustrated—could be read as a caption.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

Tenniel’s color version for The Nursery “Alice”

Tenniel worked with Edmund Evans for the first version printed in color. In the initial proof (right), the colors were generally too dark and over-saturated. Tenniel’s notes around the proof call for specific changes, reflected in the version on the left.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The Blue Caterpillar

Revised color proof bound in Lewis Carroll’s The Nursery “Alice” (London: Macmillan and Co., [1889])

Private Collection. Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015.

The Mock Turtle

From Carroll’s armored creature to Tenniel’s perfect pun

Carroll’s early sketches

Carroll’s earliest sketches (above) of the Mock Turtle show a creature with faceted armature that looks very little like a turtle. His depiction of the Gryphon is likely based on a finished drawing by his brother, Wilfred (below).

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Preliminary sketches of the Mock Turtle and Gryphon

Drawing (pen-and-ink on paper), 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

Wilfred Dodgson (1838–1914)

GryphonDrawing (pen-and-ink on paper), ca. 1862-1864

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

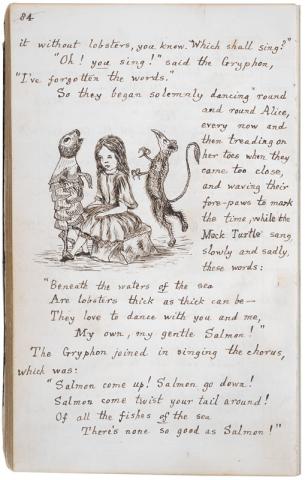

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

For his final drawings in the manuscript, Carroll refined his depiction of the Mock Turtle and gave him the furry head of a calf, picking up on his own pun about mock turtle soup.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

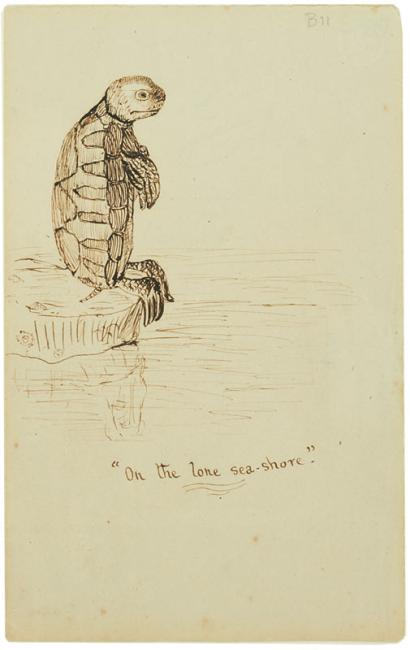

Carroll’s presentation drawing

Carroll typically used pencil for his earliest sketches; this later pen-and-ink drawing shows his most refined depiction of the Mock Turtle. Captioned “On the lone sea-shore” it does not depict a specific scene in the manuscript but may have been intended as a gift.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

“On the lone sea-shore”

Drawing (pen-and-ink on paper), ca. 1862-1865

Photography: Christ Church Library

© Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford

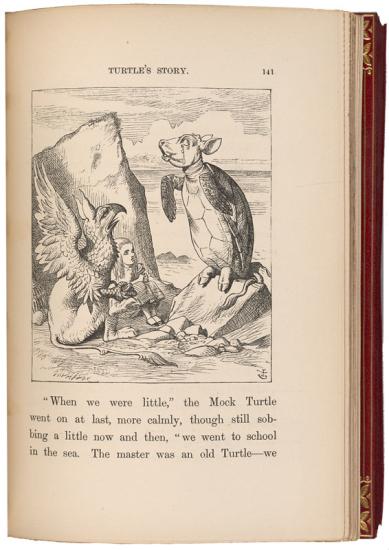

The first edition

The Mock Turtle sobs constantly throughout his story (indeed, it has trouble pausing its weeping long enough to begin). Tenniel follows the text, and shows large tears streaming down the character’s face.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.

Tenniel’s color version for The Nursery “Alice”

In the color-printed version, the Mock Turtle’s companion the Gryphon becomes vibrantly red and green, a detail not described in the text.

Image credit:

John Tenniel (1820—1914)

Gryphon and Mock Turtle Dance Round Alice

Hand-colored proof, 1885

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., 1987, 2005.202.

Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014.

Alice in Bumbleland

Tenniel regularly mined his own work for parody in the pages of Punch. In this cartoon, Alice becomes the conservative politician Arthur Balfour bumbling through a reading of the London Government Bill. Alice retains her own features here, but in the published version, her face becomes lined, and she squints at the paper through a pair of pince-nez.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

Alice in Bumbleland

Drawing (watercolor over graphite on paper), ca. 1899

Private Collection. Photography by Graham S. Haber 2015.

The White Rabbit as the Herald

From Carroll’s anonymous robes to Tenniel’s court garb

Carroll’s final drawing in the manuscript

In one of the last scenes in the manuscript (and published book), the White Rabbit discards his pocket watch and waistcoat and takes on the role of the Herald at the trial of the stolen tarts.

Lewis Carroll (1832–1898)

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

Illustrated manuscript, completed 13 September 1864

© The British Library Board, Add MS46700

Tenniel’s final drawing

In the original manuscript, Carroll’s version of the White Rabbit as the Herald is clothed in robes with designs reminiscent of a generic playing card; Tenniel refines the outfit to place the Rabbit clearly in the court of the Queen of Hearts.

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The White Rabbit as the Herald

Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865

Houghton Library, Harvard University. MS Eng 718.6 (5). Gift of Mrs. Harcourt Amory, 1927

Woodblock proofs

When the Dalziel brothers engraved Tenniel’s original design, they mistakenly cast the Rabbit’s gaze ahead. After printing the first proof (above), they spotted the error and recast his gaze askance as seen in the second proof (below).

John Tenniel (1820–1914)

The White Rabbit as the Herald

First and second state woodblock proofs, 1865

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The first edition

The published version is from the corrected woodblock. Carroll carefully designed this page so that the Rabbit’s announcement appears as a caption to Tenniel’s illustration of the same.

Image credit:

Lewis Carroll (1832—1898)

John Tenniel (1820—1914), illustrator

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

London: Macmillan, 1865

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 352027.

Photography by Graham S. Haber 2014.