Auld Lang Syne: The Story of a Song

Introduction

Three simple words—meaning "old," "long," and "since"—combine to form a phrase that translates loosely as "time gone by," "old time's sake," or, in some contexts, "once upon a time." But the old Scots phrase so gracefully evokes a sense of nostalgia that it has been embraced throughout the English-speaking world. Every December 31, millions of us raise our voices in song to greet the new year, standing with friends and looking back on days past. The song we share has its roots in an old Scottish ballad about a disappointed lover and a popular dance tune that evoked a country wedding.

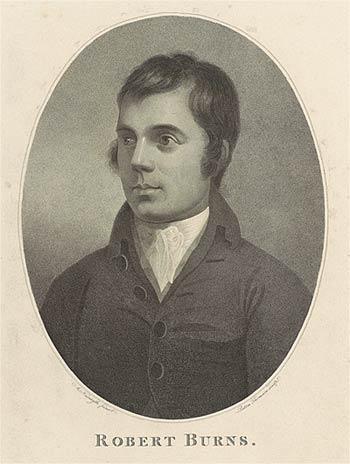

It was Robert Burns (1759–1796), the great eighteenth-century Scottish poet, who transformed the old song (and many other Scottish standards) for publication. He devoted the last ten years of his short life to collecting old verses, revising and "mending" as he saw fit, even composing poetry to accompany popular airs. When Burns turned his attention to "Auld Lang Syne," he claimed merely to have transcribed the words from "an old man's singing." But from the time his version of the song was first printed (in 1796, just after his death), it has been understood that Burns lent more than a trace of his distinctive artistry to the now-famous verses.

With rare printed editions and selections from the Morgan's collection of Burns letters—the largest in the world—this online exhibition untangles the complex origins of the song that has become, over time, a globally shared expression of friendship and longing.

This online exhibition is presented in conjunction with the exhibition Robert Burns and "Auld Lang Syne," on view 9 December 2011 through 5 February 2012, organized by Christine Nelson, Drue Heinz Curator of Literary and Historical Manuscripts.

Engraved portrait of Robert Burns (1759–1796) by Paton Thomson (ca. 1750–after 1821) after a painting by Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840). London and Edinburgh: Published by T[homas] Preston and G[eorge] Thomson, 1817. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1906

A lover's lament

"Old Long Syne"

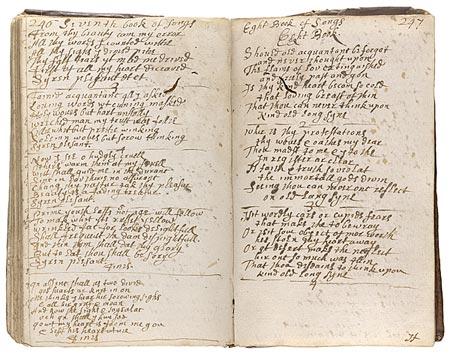

Manuscript commonplace book of James Crichton, 2nd Viscount Frendraught, 1667

Private collection

This manuscript, written in a nobleman's commonplace book from the 1660s, may be the earliest surviving rendering of a ballad beginning "Should old acquaintance be forgot." Various versions of this text circulated in manuscript during the seventeenth century before it was printed in broadside form and eventually in James Watson's Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems (1711). Though the first line is familiar, the rest of the text bears little resemblance to the enduring version published over a century later. While Burns's "Auld Lang Syne" stirs pleasant memories of carefree companionship, the "old acquaintance" of this ballad is a faithless lover ("Thou art the most disloyall maid that ever my eye hath seen"), its narrator full of bitterness and regret.

Ramsay's "Auld Lang Syne"

"Auld Lang Syne"

The Hive: A Collection of the Most Celebrated Songs

London: Printed for J[ohn] Walthoe, Jr., 1724

James Fuld Music Collection, 2008

Yet another song beginning Should auld acquaintance be forgot appeared in print before Burns adopted the familiar line. Poet Allan Ramsay, whose passion for Scottish folk tradition inspired Burns, published this version in 1724. While the tone approaches the bittersweet nostalgia we now associate with "Auld Lang Syne," it is not surprising that Burns's graceful rendering outlasted Ramsay's stilted lines: Methinks around us on each bough a thousand Cupids play, whilst thro' the groves I walk with you, each object makes me gay.

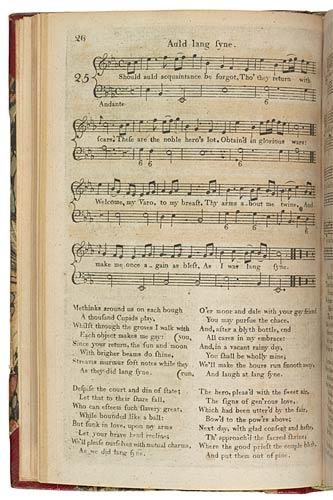

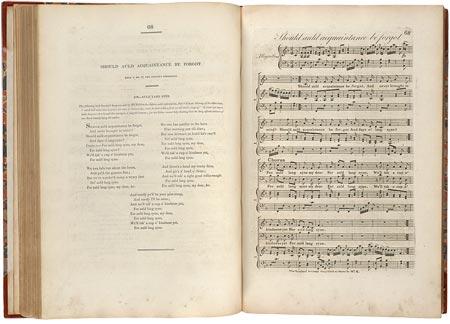

Ramsay's version, reprinted with music

"Auld Lang Syne"

The Scots Musical Museum, vol. 1

Edinburgh: Printed & sold by Johnson & Co., 1787

Gift of Charles Ryskamp in memory of Edward S. Bentley, 1975

Poet Allan Ramsay's version of "Auld Lang Syne," which was first published in the 1720s, appeared again a few decades later, set to a traditional air, in the first volume of James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum. (In 1796, in a later volume of the Museum, Johnson published the Burns version of "Auld Lang Syne" for the first time.)

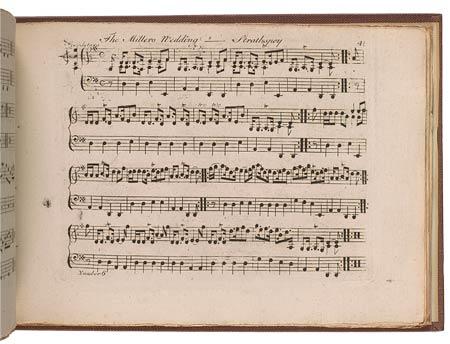

A Caledonian country dance

"The Miller's Wedding"

A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances

London: Printed & sold by Robert Bremner, [1760s]

James Fuld Music Collection, 2008

In his quest to document and preserve Scottish song, Burns combed through published collections and traveled the countryside to find worthy examples. He often turned to popular dance music, freely adapting traditional verses to suitable melodies. Robert Bremner's Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances was an important source. It included "The Miller's Wedding," sometimes called "The Miller's Daughter," a strathspey (a type of Scottish dance) that includes a very subtle hint of the tune we now call "Auld Lang Syne."

William Shield's Rosina

Rosina, A Comic Opera

London: Printed for William Napier, [1783?]

James Fuld Music Collection, 2008

When Shield's comic opera Rosina was first performed at Covent Garden in 1782, Scottish song enthusiasts may have recognized a snippet of melody played by oboe and bassoon, in imitation of bagpipes, toward the end of the overture. It was reminiscent of "The Miller's Wedding," a popular Scottish country dance tune that foreshadowed the melody we now call "Auld Lang Syne." Shield included several such folk references in the opera, and this one led to repeated claims—entirely erroneous—that he had composed the now-famous air. (The relevant passage begins at the section marked Allegro.)

The tune of "Auld Lang Syne"

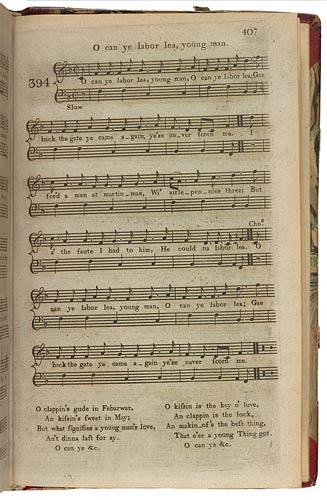

"O Can Ye Labor Lea, Young Man"

The Scots Musical Museum, vol. 4

Edinburgh: Printed & sold by Johnson & Co., 1792

Gift of Charles Ryskamp in memory of Edward S. Bentley, 1975

In Burns's day it was not unusual to pair verses with whatever popular tune provided a good metrical fit. Listen to a bit of this song, for example, and you will recognize a familiar melody. With roots in an old Scottish dance tune, this air was finally paired with the words of "Auld Lang Syne" in 1799. But the tune continued to have a life of its own. In the United States, it served as a popular accompaniment to antislavery poems such as William Lloyd Garrison's "I am an abolitionist! I glory in the name." Katharine Lee Bates's poem "America the Beautiful" was often sung to this tune (and many others) before becoming inextricably linked with a composition by Samuel Ward.

First publication of the Burns verses

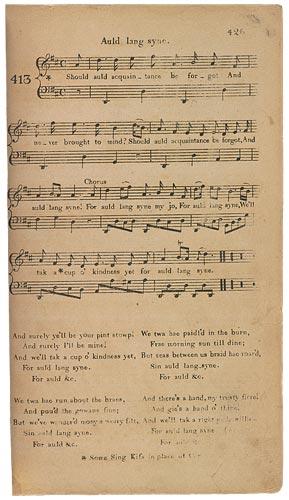

"Auld Lang Syne"

The Scots Musical Museum, vol. 5

Edinburgh: Printed & sold by Johnson & Co., 1796

The James Fuld Music Collection, 2008

The now-familiar words of "Auld Lang Syne" were first published here, in the fifth volume of James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum, an invaluable compilation to which Burns was the principal contributor. The tune, however, is not the one we sing today. In fact, Johnson set an altogether different set of verses ("O Can Ye Labor Lea") to the air we now associate with "Auld Lang Syne." The Museum employed a code to indicate the source of each song; this entry was marked Z, for "old verses, with corrections or additions." It was Burns, of course, who had refurbished the traditional song, though he preferred to minimize his role.

An old song of olden times

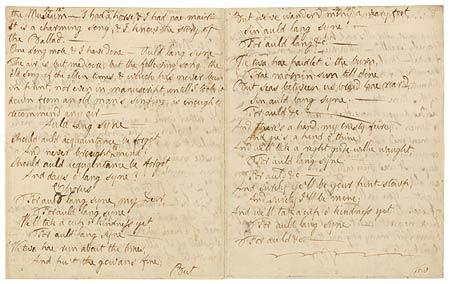

Letter to George Thomson, incorporating a manuscript of "Auld Lang Syne," September 1793

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1906

In 1793, Robert Burns filled a twenty-page letter with comments on seventy-four songs that editor George Thomson had proposed to include in a musical anthology. Burns then offered Thomson "one song more": this manuscript of "Auld Lang Syne." Burns claimed (perhaps disingenuously) to have transcribed the text as he listened to an old man singing a traditional song. As for the tune then associated with the words, Burns considered it "but mediocre," and Thomson apparently agreed: when he published "Auld Lang Syne" in his Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs in 1799 (after Burns had died), he substituted a different tune—the one we sing today.

This text begins on the fourth line of the manuscript. In the transcription of "Auld Lang Syne," the Scots words have been underlined and an English translation provided in parentheses.

One Song more, & I have done. Auld lang syne—The air is but mediocre; but the following song, the old Song of the olden times, & which has never been in print, nor even in manuscript, untill I took it down from an old man's singing; is enough to recommend any air.

Auld Lang Syne

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, (old)

And never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days o' lang syne!

For auld lang syne, my Dear,

For auld lang syne,

We'll tak a cup o' kindness yet, (take)

For auld lang syne.

We twa hae run about the braes, (two, have, hills)

And pu't the gowans fine; (pulled/daisies)

But we've wander'd mony a weary foot, (many)

Sin auld lang syne. (since)

We twa hae paidlet i' the burn, (two/have/paddled/in/brook)

Frae mornin' sun till dine: (from/dinnertime)

But seas between us braid hae roar'd, (broad/have)

Sin auld lang syne. (since)

And there's a hand, my trusty feire, (friend)

And gie's a hand o' thine; (give us)

And we'll tak a right gude-willie waught, (goodwill draft)

For auld lang syne.

And surely ye'll be your pint-stowp, (buy/cup or tankard)

And surely I'll be mine; (buy)

And we'll tak a cup o' kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

Words and melody, together at last

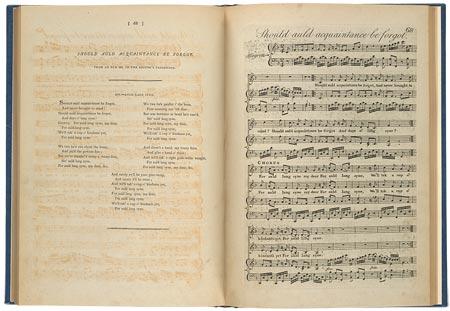

"Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot"

A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs for the Voice

London: printed & sold by Preston; sold also by the proprietor G[eorge] Thomson, Edinburgh, 1799

James Fuld Music Collection, 2008

In 1799, a few years after Burns had died, "Auld Lang Syne" as we know it appeared in print for the first time. While the words had already been published with a different tune, and the tune had been published with different words, it was George Thomson, an Edinburgh-based music seller and amateur musician, who finally brought them together in his Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs, a major compilation to which Burns contributed countless songs. Thomson claimed (on the left-hand page) that his source was "an old MS. in the editor's possession," when in fact Burns had sent him the text just a few years before. In later editions, Thomson dropped the misleading word old.

A question of authorship

"Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot"

A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice

London: Printed & sold by T[homas] Preston; sold also by G[eorge] Thomson, the editor & proprietor, Edinburgh, 1817

Purchased in 1974

George Thomson republished "Auld Lang Syne" in this 1817 edition with a new arrangement by the Czech composer Leopold Kozeluch (1747–1818), the "Mr. K." cited at the foot of the piano score. While in the earlier edition Thomson had cited "an old manuscript" as the source of his text, here he was more forthcoming: he quoted the letter in which Burns claimed to have taken down the words "from an old man's singing." Thomson added his opinion about the authorship of the song: "It seems not improbable . . . that he said this merely in a playful humour; for the Editor cannot help thinking that the Song affords evidence of our Bard himself being the author."

A 19th century revision

"Auld Lang Syne"

The New Pocket Song Book

New York: Leavitt and Allen, [between 1856 and 1860]

James Fuld Music Collection, 2008

Even after the Burns version of the words of "Auld Lang Syne" was published in 1796, new adaptations appeared. This sentimental nineteenth-century example was printed in an American book of popular songs that also included "Home Sweet Home" and "Yankee Doodle."

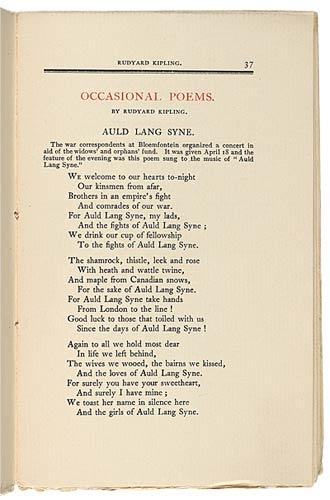

Kipling's wartime version

"Auld Lang Syne"

Occasional poems

Cornhill booklet, vol. 1, no. 2. Boston: 1900

Acquired in 1943

During the Boer War, Kipling composed a new set of lyrics to be sung to the tune of "Auld Lang Syne" at a benefit concert for military widows and children. His version was first published as a broadside in South Africa and was reprinted in this American keepsake edition.