Persian poetry

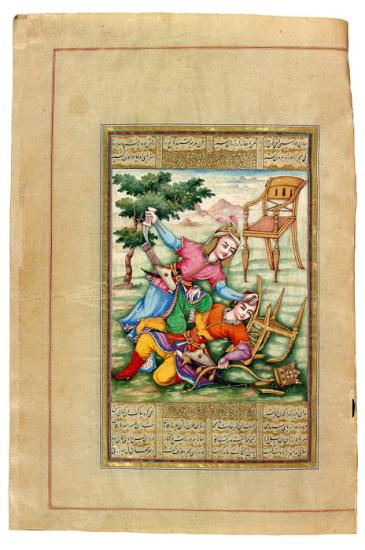

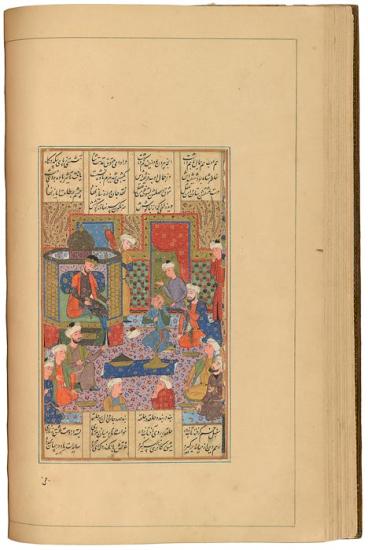

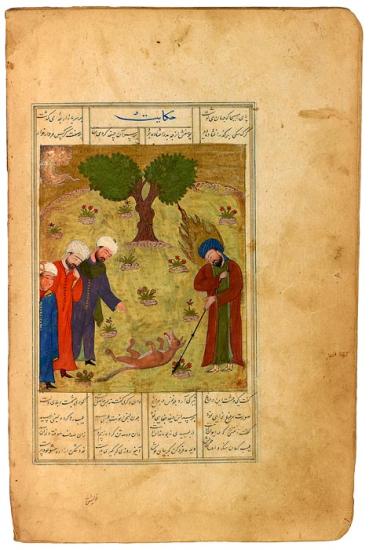

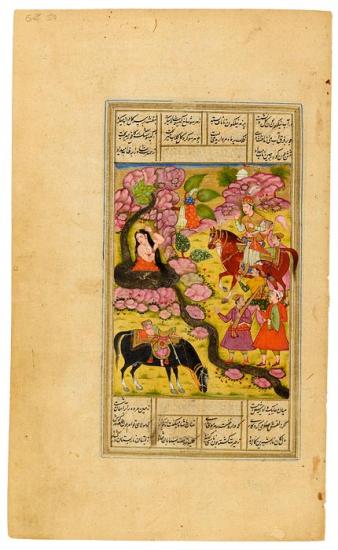

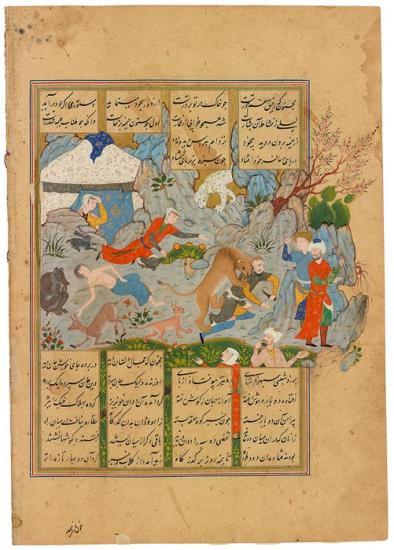

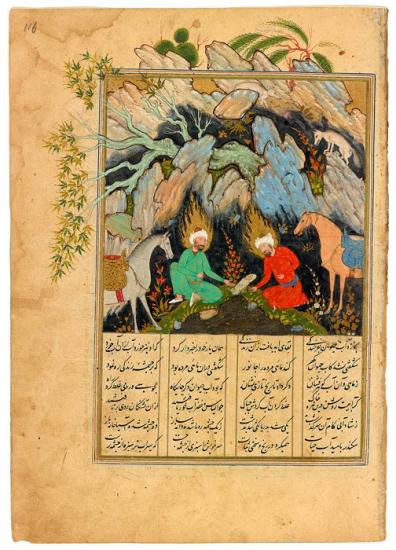

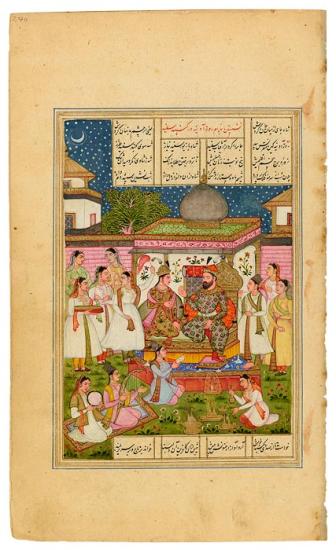

Tur Murders Iraj, His Brother

Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), in Persian

Written between 1852 and 1856 by Calī Ibn al-Ḥusain al-Kātib al-Shīrāzī, with miniatures by Luṭf Calī Khān al-Shīrāzī.

The Dannie and Hettie Heineman Collection, gift of the Heineman Foundation, 1977

This miniature appears in a nineteenth-century manuscript of Firdausī's Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the Persian national epic. Firdausī wrote the epic—in some 50,000 couplets—between 980 and 1010. He tells the story of the mythical Persian king Feraydun, who had three sons, Salm, Tur, and Iraj. He divided the world into three parts, prudently giving Persia and the lands of the Arabs to Iraj, his youngest and wisest son. Tur and Salm were displeased that Iraj should have received the crown, sword, seal, and ivory throne of Persia and plotted against him. Iraj visited them, willing to hand over the crown, but the enraged Tur broke his throne over Iraj's head, pulled a dagger from his boot and killed him. Iraj's head was sent to the king. Years later his death was avenged by his grandson Manuchehr.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

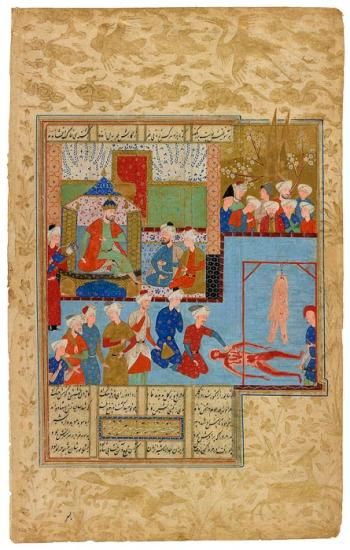

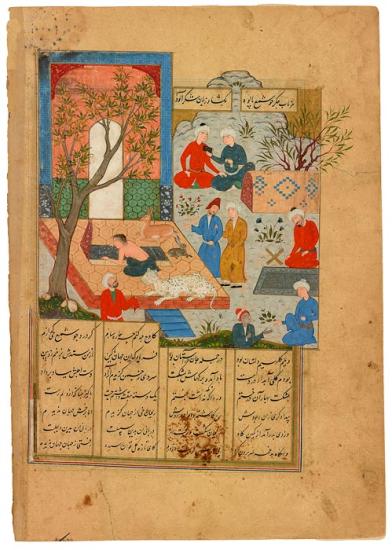

King Shaput Zu˒l Aktaf

King Shaput Zu˒l Aktaf Observes Mani's Flayed Body

Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), in Persian

Promised gift of William M. Voelkle.; voelkle leaf

This miniature appears in a sixteenth-century manuscript of Firdausī's Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the Persian national epic, written between 980 and 1010. He tells the story of Mani (ca. 216–276), a painter and prophet from China, who sought an audience with the king, Shapur, to seek his support as a prophet of a new religion. Shapur had doubts about his creed, however, and Mani was unable to address Shapur's remarks concerning the faith of Zoroaster. The enraged king had Mani flayed and his skin stuffed with straw so that no one would be tempted to follow his teachings. Representations of the subject are extremely rare. Mani was the founder of Manichaeanism, but he actually died in prison during the reign of Bahrām I, Shapur's second successor.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

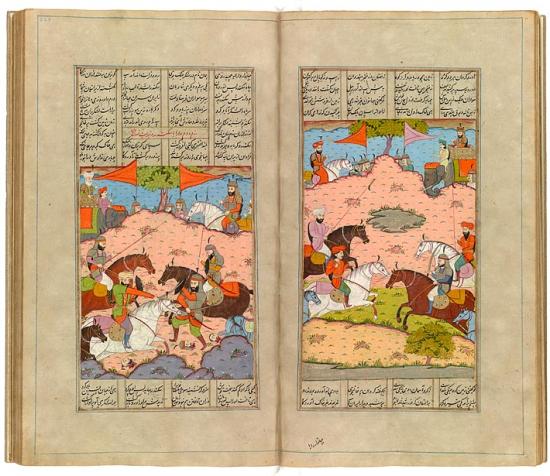

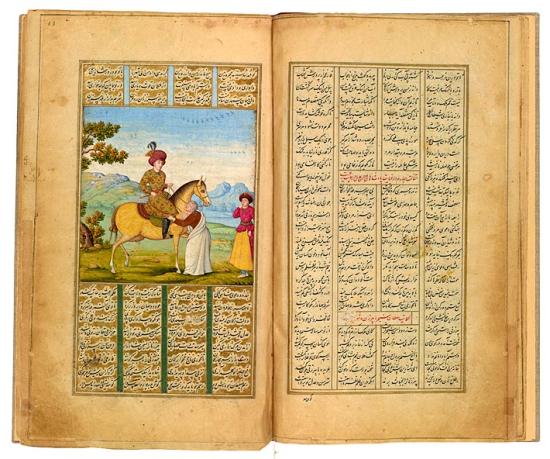

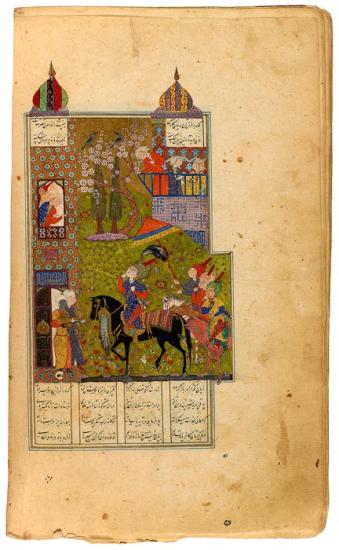

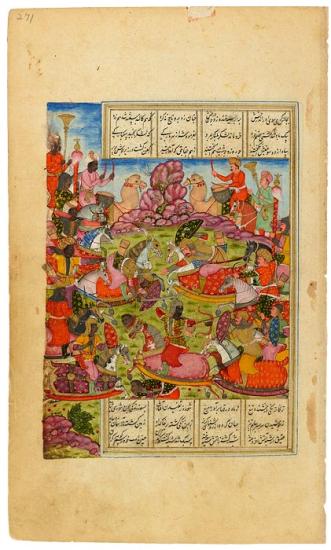

Iskandar and Dārā

The Armies of Iskandar and Dārā Battle

Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), in Persian

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Iskandar (Alexander the Great) was regarded as a great hero; his stories appear in several works, such as Firdausī's Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the Persian national epic, and Niẓāmī's Khamsa. Firdausī wrote the epic—in some 50,000 couplets—between 980 and 1010. Shown here are the first two battles between the armies of Iskandar and Dārā (Darius), those at Issus (333 B.C.) and Gaugamela (331 B.C.) Both were won by Iskandar. Lahore flourished under the Mughals, but when this manuscript was made it was the capital city of the Sikhs, who were much indebted to Mughal culture.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

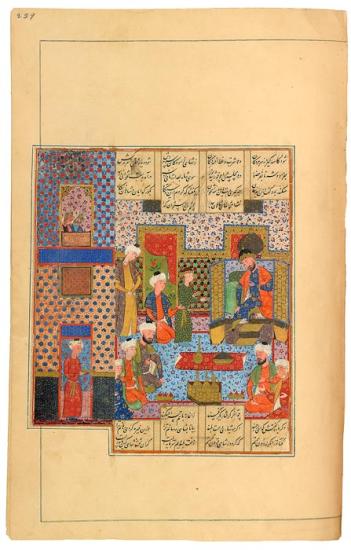

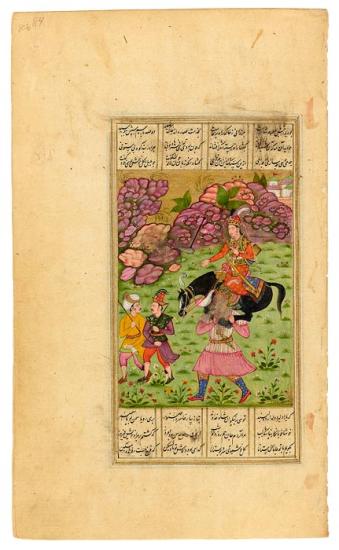

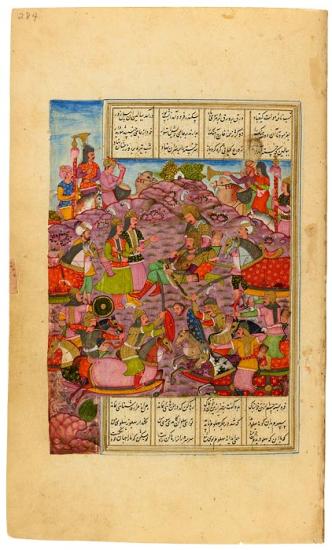

Bones Before Iskandar

A Young Prince Holds His Father's Bones Before Iskandar

Haft aurang (Seven Thrones), in Persian, written by Ḥasan al-Ḥusainī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

The poet Jāmī's Haft aurang consists of seven romantic and didactic masnavīs (narrative poems in rhyming couplets), the last treating stories about the wisdom of Iskandar (Alexander the Great). Here Iskandar converses with a young prince whose region he recently conquered. The youth, the only surviving member of his royal family, shows Iskandar the bones of his father, the dead king, He hopes to demonstrate that the bones look no different than those of commoners and that conflict among men is senseless. Jāmī was one of the last great Sufi scholars and poets. The term Haft aurang also refers to the seven stars comprised by the Big Dipper (Ursa Major).

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Maḥmūd of Ghanzi

Maḥmūd of Ghanzi Orders His Favorite Page, Ayāz, to Cut off Half of His Beautiful Curly Locks

Haft aurang (Seven Thrones), in Persian, written by Ḥasan al-Ḥusainī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Maḥmūd of Ghazni (r. 997–1030) was the greatest ruler of the Ghaznavid dynasty, controlling Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India. He was the first to bear the title Sultan (authority), was a patron of the arts and of poetry, and commissioned Firdausī to write his famous Shāhnāma, the Persian national epic. But he became even more celebrated, by such poets as Jāmī and Sa˓dī, because of his love for Malik Ayāz, his young male slave. When the king asked him if he knew of a greater and more powerful king, he said yes, explaining that even though Maḥmūd was king, he was ruled by his heart, and that Ayāz was the king of his heart. Thus, the power of Maḥmūd's love made him a slave to his slave.

Jāmī's Haft aurang (Seven Thrones or Constellations of the Great Bear), was written from 1468 to 1485, and consists of seven poems in masnavī form (rhyming couplets); some are allegorical, others are didactic. In his discourse on beauty he tells the story of Maḥmūd and his love for Ayāz, who had many good points, but was not remarkably handsome. One night, under the influence of wine and Ayāz's beautiful curls, love and desire began to stir in him, and he feared that he might verge from the Path of Law and the Way of Chivalry. He then gave Ayāz his knife, ordering him to cut off half the length of his curls, which he did. His ready obedience provided a new rush of love, causing him to bestow upon Ayāz even more gold and jewels, after which Maḥmūd fell into a drunken sleep. In the morning, realizing what he had done, called for Ayāz and saw the clipped tresses. He was somewhat cheered by the poet Unsuri's quatrain.

Though shame it be a fair one's curls to shear,

Why rise in wrath or sit in sorrow here?

Rather rejoice, make merry, call for wine:

When clipped the cypress doth most trim appear.

In 1021 Maḥmūd gave Ayāz the throne of Lahore. Maḥmūd himself died at fifty-nine, had nine wives, and nearly fifty-six children with almost three dozen women.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

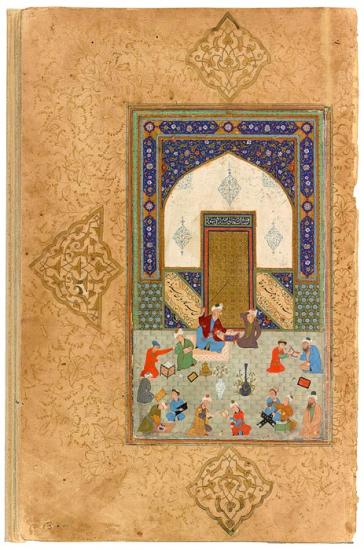

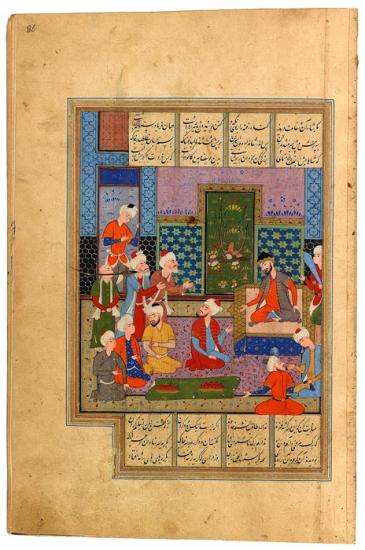

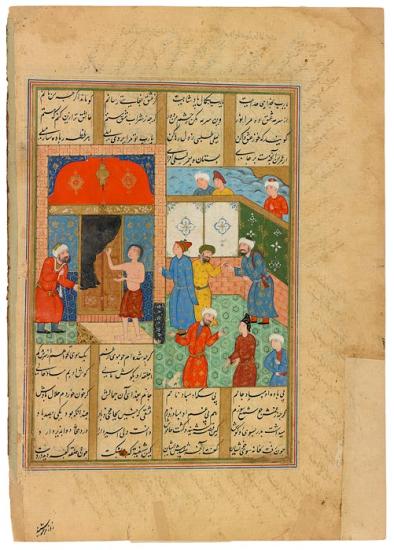

Classroom Scene

Classroom Scene

Shāh va darvish (The King and the Dervish), in Persian

Finished 19 January 1540, written by Mīr Calī al-Kātib al-Sulṭānī, probably for Cabd al-caziz Sulṭān.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913

Hilālī, a Persian poet of Turkish origin, wrote three masnavīs (narrative poems in rhyming couplets), including a Lailā and Majnūn story with a happy ending and the present work, which was criticized in the memoirs of Bābur, the future Mughal emperor. Hilālī had made the dervish the lover and the king the beloved, making him a shameless strumpet.

School scenes were especially popular in Bukhara, reflecting the current emphasis on public education, and were derived from those depicted in the story of Lailā and Majnūn. The headmaster is about to strike a student, who catches his turban. Other students read, misbehave, write, or polish paper (left corner). ˓Abd al-˓Aziz Sulṭān (d.1549), for whom this manuscript is believed to have been commissioned, established a library that was supposedly without equal.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

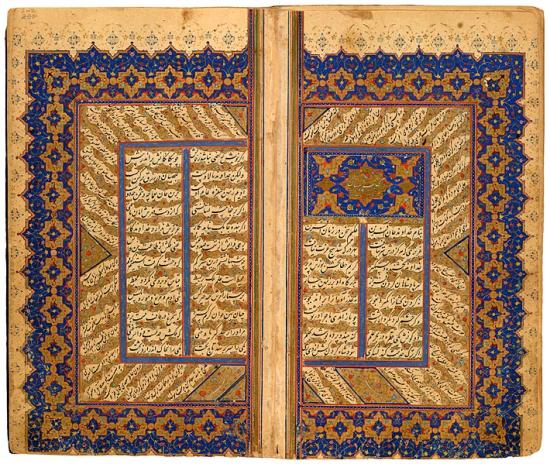

Sa˓dī Shīrāzī's Būstān

Double-Page Opening for Sa˓dī Shīrāzī's Būstān

Kulliyyat (Collected Works), in Persian, written by Hidayāt al-Kātib al-Shīrāzī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913

Sa˓dī Shīrāzī, Anwari, and Firdausī were regarded as the three Persian Prophets of Poetry. There are no integral miniatures in this copy of Sa˓dī's Kulliyyat, but some of its major textual divisions are marked with ornate double-page headings (sarlauḥs). Such is the case with his two most famous works, the Būstān (The Orchard) and the Gulistān (The Rose Garden). In the latter, Sa˓dī wrote that "The children of Adam are limbs to each other, having been created of one essence." This was quoted by President Obama in an address to the Iranian people in 2009, when he argued that differences should not define us.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

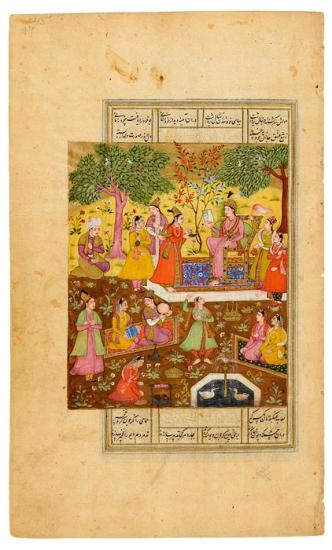

Gathering in a Graveyard

Gathering in a Graveyard

Dīvān (Poems), in Persian

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan before 1913

The author of his poem was known simply as Ḥāfiẓ, a name designating "one who knew the Qur˒an by heart." He was regarded as the greatest master of the Persian ghazal (love lyric) and his Dīvān remains popular to this day. Because of the sweetness of his poetry he was called Chagarlab (Sugar Lip). Here a convivial gathering, complete with wine and music, takes place in a cemetery. The low wooden cenotaph rests on a base of white marble. At the top of the page is the famous couplet:

Sit not at our tomb without wine and minstrel

That I may rise dancing from the grave at your aroma.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Cisa (Jesus) and the Dead Dog

Cisa (Jesus) and the Dead Dog

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

The Makhzan al-asrār (Treasury of Secrets) is the first (ca. 1175) of five long narrative poems making up Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). Through example, its twenty discourses deal with religious and ethical topics. Here, in an illustration of the tenth discourse, Jesus encounters a dead dog, about which three men make cruel remarks. But Jesus, disregarding faults and finding virtue, tells them that pearls are not as white as the dog's teeth. The moral: do not seek the faults of others and your own merit, but turn your eyes to yourself. The flaming halo denotes Christ as a prophet and saint.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Sultan Sanjar and the Old Woman

Sultan Sanjar and the Old Woman

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written 1674–75 by Ghiyās al-Dīn Maḥmūd Ibn Salīm Lātī, with miniatures ca. 1700–1715 inscribed (probably erroneously) to Muḥammad Zamān and his brother Ḥājī Muḥammad.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Here, to the amazement of an aide, an old woman grasps the hem of the coat of Sultan Sanjar (r. 1117–57) as he is about to go out hunting. She has come to complain of her mistreatment by the sultan's soldiers, but the Seljuq ruler tells her that the complaint is laughable when compared with his many successful conquests. "What good is it to conquer territories," she answers, "if you do not control your soldiers?"

The story is told in the fourth discourse of Niẓāmī's moralizing Makhzan al-asrār (Treasury of Secrets), the first (ca. 1175) of five long narrative poems that make up his Khamsa (Quintet). The name of the artist, Muḥammad Zamān, and the date 1086 (1675) below the old woman were probably added in error.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Khusrau Seels Pardon from His Father

Khusrau Seels Pardon from His Father

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

After a hunt, Prince Khusrau and his companions descend on a peasant's house, where drunken revelry ensues. Even the prince's horse breaks loose, trampling new crops. The punishment is severe: the horse's hooves are cut, and the prince's throne is given to the peasant. Khusrau, who begs two elders to plead for his pardon, exhibits strong remorse. Dressed in a shroud and weeping, he offers his sword and his head, saying that he could endure any sorrow but the anger of his father. Here, curiously, Khusrau holds the sword with his teeth! Hurmuzd is moved, kisses his son, forgives all, and restores him as crown prince. Khusrau (Chosroes II) was king of Persia from 590 until 628.)

This episode appears in Khusrau va Shīrīn (1180), the second story in Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet).

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Shīrīn

Shīrīn, an Armenian Princess, Looks at a Portrait of Khusrau

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Khusrau, in a dream, learned from his grandfather that he was destined to have Shabdīz, the world's swiftest steed, and Shīrīn, an Armenian princess whose sweetness and beauty would sustain him for as long as he lived. Khusrau's dearest friend was Shāpūr, a painter whose portraits captured both the likeness and the soul of the subject. As it happened, Shāpūr had seen Shīrīn on a trip to Armenia, and he was now sent to find her on Khusrau's behalf. In Armenia, Shāpūr sketched a portrait of Khusrau and hung it on a tree in a meadow frequented by Shīrīn, hoping she would discover it. Shīrīn had a handmaiden bring the portrait of the handsome man to her, but fearing it was the work of evil spirits, had it destroyed. The next morning Shāpūr hung a second portrait on a tree, but Shīrīn's maid refused to fetch it. The third morning, in another meadow, Shāpūr hung a third portrait. This time, overcome with love, Shīrīn herself took it from the branch. In the miniature Shīrīn holds the magic portrait in her hands and is transfixed by the handsome prince, wondering who he was. Eventually Shāpūr, seated at the far left, tells her about Khusrau's dream of their destined love.

This episode appears in Khusrau va Shīrīn (1180), the second story in Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet).

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Khusrau Encounters Shīrīn Bathing

Khusrau Encounters Shīrīn Bathing

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Khusrau, in a dream, learns that one day he will wed Shīrīn, an Armenian princess, and own her mother's horse, Shabdīz, the world's fastest steed. He entrusts his friend Shāpūr to arrange her flight to Persia on Shabdīz. Meanwhile Khusrau heads for Armenia and comes upon Shīrīn bathing in a pool. As he nears, his finger raised to his mouth in astonishment, he tells himself he would like to have such a beautiful maiden and horse, little knowing that one day both will be his. As Shīrīn rides away, she wonders if the stranger who startled her might have been Khusrau, though he was not in the anticipated red garb.

This episode appears in Khusrau va Shīrīn (1180) is the second story in Niẓāmī's Khamsa.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Shīrīn

Shīrīn Entertains Khusrau in a Walled Garden

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Khusrau and Shīrīn went to Armenia, and visited her aunt, Queen Mihin Banu, who prepared many festivities and celebrations worthy of the king. Here, in a walled garden, on a moonlit night with many candles, the couple is seated on a low platform. Shīrīn offers Khusrau a cup of wine. The, queen, however, only permitted them to sit side by side in public after Shīrīn promised her that she would not be his before they were married. Nor did the queen permit them to be alone.

This episode appears in Khusrau va Shīrīn (1180), the second story in Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet), a long poem that addresses religious and ethical topics.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Farhād Carries Shīrīn

Farhād Carries Shīrīn and Her Black Horse, Shabdīz, Down Mount Bisutum

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Khusrau, in order to seek peace between Persia and Byzantium, had to marry the king's daughter, Maryam, promising to take no other wife. Meanwhile, Shīrīn's aunt died, became the ruler of Armenia, and eventually heard of Khusrau's marriage. But they were still loyal to each other and wanted to meet. Shīrīn, who did not have access to milk, commissioned Farhād (a friend recommended by Shāpūr) to build a channel connecting her pasture to the palace. Farhād fell madly in love with Shīrīn. When Khusrau learned of his devotion, Khusrau asked him to cut a road through Mount Bisutum. After he arrived there he sculpted images of Shīrīn and Khusau Riding Shabdīz. When Shīrīn learned of Farhād's sculptures she went to visit him on Mount Bisutum, stirring his passions all the more. When she left, her horse stumbled, doubtless tired from the ascent up the mountain. Farhād, who was exceedingly strong, then picked up both Shīrīn and her horse, carried them down the mountain, and to the gate of her palace.

This episode appears in Khusrau va Shīrīn (1180), the second story in Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet).

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Shīrīn Lectures Khusrau

Shīrīn Lectures Khusrau

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mun˓im al-Din al-Auḥadī

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Deeply pained to learn that Khusrau was responsible for his rival Farhad's death as well as of the prince's affair with Shekar of Isfahan, Shīrīn will speak to him only from the roof when he comes to her palace to beg forgiveness. She reproaches him for causing her to suffer and for being merry from wine. If he is seeking love, he must be sober and marry her. They are then united in perfect love.

Many years later, Khusrau's son, lusting after his throne and wife, imprisoned him in a dungeon, where he was assassinated. After the splendid burial, Shīrīn, who had agreed to marry him, asked to be left alone for a final farewell, locked the vault door, and fatally stabbed herself.

This episode appears in Khusrau va Shīrīn (1180), the second story in Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet).

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Lailā and Qais in School

Lailā and Qais in School

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

The children of two great chieftains, Lailā and Qais were sent to study under a learned teacher. When Lailā entered the schoolroom, love awakened in Qais's heart, and he vowed to love her all his life. Thereafter he was able to do little else but stare at her, continually repeating her name. Others said he behaved like a madman, losing his heart and soul. People called him a madman, or majnūn, and henceforth he was known as Majnūn. Forbidden to see Lailā, he withdrew to the desert and befriended beasts. In the miniature, a youth, perhaps meant to be Qais, sits among the girls in the foreground.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

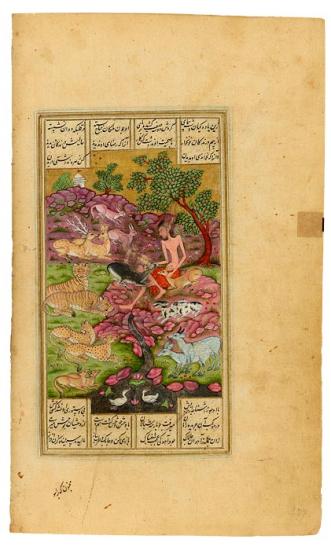

Majnūn Surrounded by Pairs of Animals

Majnūn Surrounded by Pairs of Animals in the Wilderness

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Because of his love for Lailā, Majnūn not only became a madman but also a poet. A father had lost a son, and he was a prisoner in the land of love. He became increasingly separated from his friends, taking refuge in the wilderness. The wild animals did not attack him, or each other, becoming tame and friendly with the stranger in their midst. He became their friend and master, and they protected him. Although he withdrew from public society, the intensity of his love for Lailā never diminished.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Majnūn Grasps the Door Knocker

Majnūn Grasps the Door Knocker of the Kaaba

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, illustrated ca. 1579 by Siyāvush the Georgian and his workshop for ˓Alī Khān (Beg Turkman).

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

In order to cure Majnūn, his father takes him on a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he hopes that his son will ask to be saved from his passion. Instead, Majnūn grasps the door knocker of the Kaaba and cries, "I pray to You, let me not be cured of love, but let my passion grow! Make my love a hundred times as great as it is this very day!" Nothing further can be done, for Majnūn can never be cured, having blessed Lailā and cursed himself before the Holy Shrine. His father, full of grief, returns home, and Majnūn, whose life is threatened by Lailā's father, again retreats into the desert.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

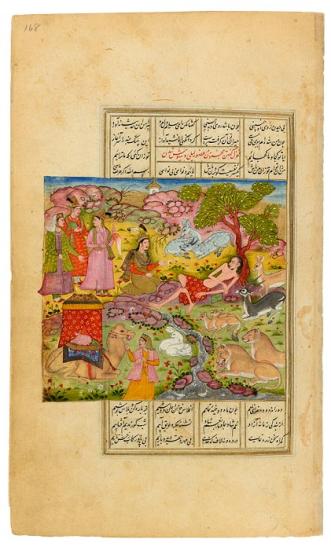

Lailā Visits Majnūn

Lailā Visits Majnūn in the Wilderness

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Lailā, with four companions, visits Majnūn in the wilderness. Majnūn, reclining beneath a tree, is surrounded by tame animals.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Lailā Summons Majnūn

Lailā Summons Majnūn to Her Camp

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, illustrated ca. 1579 by Siyāvush the Georgian and his workshop for ˓Alī Khān (Beg Turkman)

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

Although Lailā had been forced to marry Ibn Salam, he resigned himself to simply beholding her beauty, as she refused to submit to him. Lailā's thoughts were always about Majnūn, and she wanted to see how he was. Through the aid of an old man, they found a way to exchange messages. At the upper left, a messenger informs Majnūn of the plan to meet in a thicket near Lailā's camp, shown on the lower right. He holds a book of his poems, which he plans to read to her.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Majnūn Visits Lailā's

Majnūn Visits Lailā's Camp for the Last Time

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, illustrated ca. 1579 by Siyāvush the Georgian and his workshop for ˓Alī Khān (Beg Turkman)

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

Finally the two ill-fated lovers are to meet; however, overcome by emotions, they faint. They are, however, protected by Majnūn's animal entourage, and a lion attacks a man who attempted to approach them. A man at the lower right raises he finger to his mouth in astonishment. (After the tears of the old man who arranged the meeting revive Majnūn, the most beautiful verses he has ever composed flow from his lips. But after reciting a few, he suddenly rises and flees into the desert.)

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Majnūn Mourns at Lailā's Tomb

Majnūn Mourns at Lailā's Tomb

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, illustrated ca. 1579 by Siyāvush the Georgian and his workshop for ˓Alī Khān (Beg Turkman)

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

Lailā knew that Majnūn would come to mourn her, and had asked her mother to tell him that she had always remained true, and that she should be buried in bridal clothes. Majnūn comes repeatedly to mourn, watched over by his animals. On his last visit, he embraces the gravestone with both hands, and when he utters the words You, my love... , his soul leaves his body. The animals remain until nothing is left but his bones. Members of both tribes weep, and Majnūn is buried at Lailā's side. Some see Majnūn's love for Lailā as a metaphor for his all-consuming love of God.

Faithful in separation, true in love,

One tent will hold them in the world above.

Lailā va Majnūn (1188), a Persian Romeo and Juliet, is the third poem of the Khamsa (Quintet), a multi-part work by the poet Niẓāmī. The story is based on two real-life seventh-century lovers.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Iskandar Battles the Zangīs

Iskandar Battles the Zangīs

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

The fourth poem in the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet) is the Iskandarnāma (1194), consisting of stories about Iskandar (Alexander the Great). Iskander, the king of Rūm, had sent his messenger/orator Tūtiyā-Nosh to the African king of Zang, who, out of rage, killed the beautiful messenger, decapitated him, and drank his blood. The miniature depicts the defeat of the African army of Zang by Iskandar's army. The drummers for each side are on camels at the top, while the defeat is shown in the middle ground. In the foreground the Zangīs flee. After his return from victory Iskandar laid the foundations of Alexandria.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Iskandar Comforts the Dying Dārā

Iskandar Comforts the Dying Dārā

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

Stories about Iskandar (Alexander the Great) were very popular and appear in Firdausī's epic Shāhnāma (Book of Kings) and, as here, in the fourth poem of Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet), the Iskandarnāma (1194). In his quest to conquer Persia, Iskandar twice defeated Dārā (Darius III, r. 336–330 B.C.): in the battles at Issus (333 B.C.) and Gaugamela (331 B.C.) Before he could capture Dārā in another battle, two of Dārā's closest advisors conspired to stab him. Iskandar weeps as Dārā dies in his arms, asking Iskandar to care for his family and seek the hand of his daughter Roshanak in marriage. He then honors the deceased monarch with a royal burial. The two advisors, who stand before Dārā, thought their deed would be rewarded, but they were hanged instead.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Khiżr żand Ilyās

Khiżr żand Ilyās at the Fountain of Life

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, illustrated ca. 1579 by Siyāvush the Georgian and his workshop for ˓Alī Khān (Beg Turkman)

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

Iskandar (Alexander the Great) and Khiżr, his vizier, set out to reach the end of the world in order to find the Water of Life. They took different paths, however, and only Khiżr found it, achieving immortality. Here he is shown with Ilyās (Elijah). Their dried fish, which accidentally fell into the water, has been miraculously revived. Witnessing the miracle, they achieve prophethood, symbolized by their flaming gold halos. The Prophet Muḥammad reportedly said that Khiżr and Ilyās spend every month of Ramadan in Jerusalem. Khiżr may be the figure on the left, as his name in Arabic means "the green one."

This episode appears in the Iskandarnāma (1194), the fourth poem of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet).

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

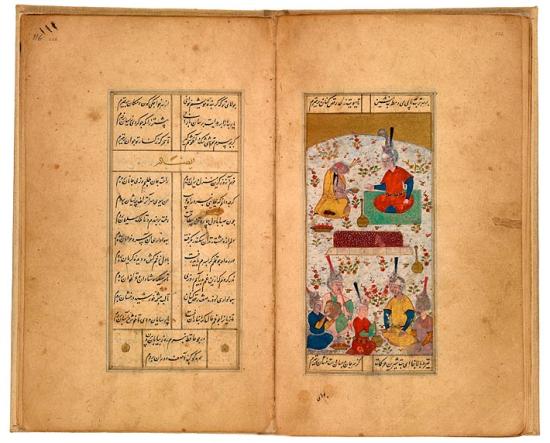

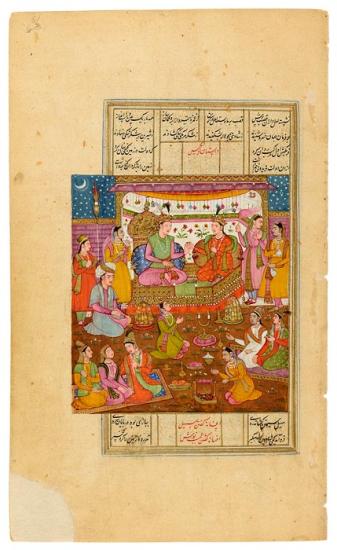

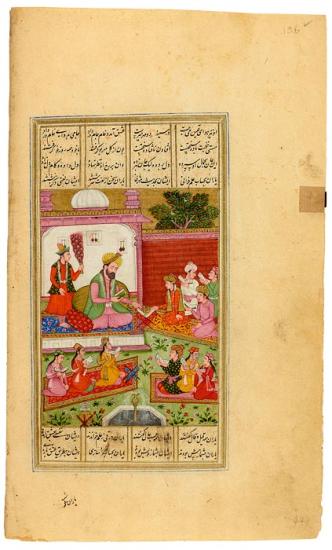

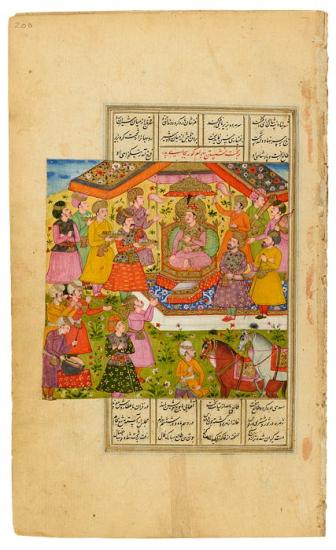

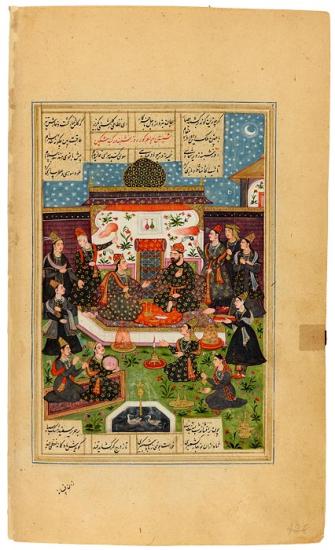

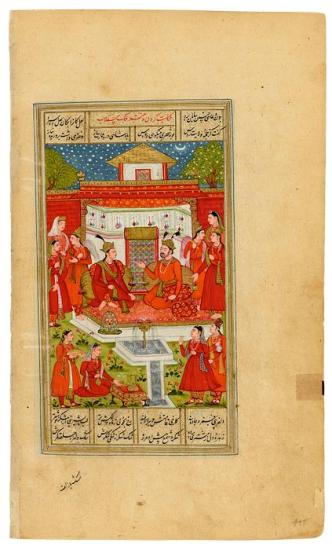

Bahrām Gūr and His Court

Bahrām Gūr and His Court

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

In the miniature, Bahrām Gūr is enthroned, surrounded by sixteen members of his court. Some of them offer gifts in bowls and two hold fly whisks. There is also a military band, as well as a groom with two horses.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

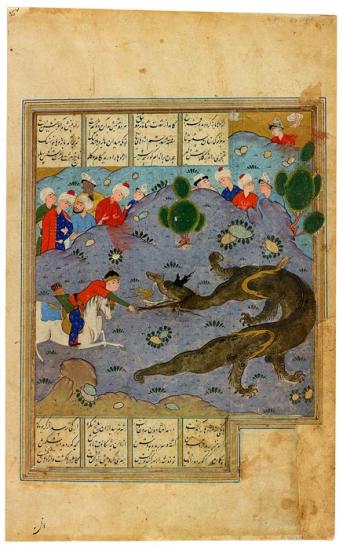

Bahrām Gūr Slays a Dragon

Bahrām Gūr Slays a Dragon

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian

Bequest of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, as he pursues a wild ass, Bahrām comes upon a dragon, which has just eaten the ass's foal. Called to do justice, he kills the dragon, cuts open its stomach, and sees the foal. Bahrām follows the avenged ass into the dragon's cave to discover great treasures. At the end of his life, Bahrām saw a wild ass enter a cave. Thinking it an omen, he followed it but was never seen again. Gūr, meaning "wild ass," had found the tomb (gūr) he sought—a play on words.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

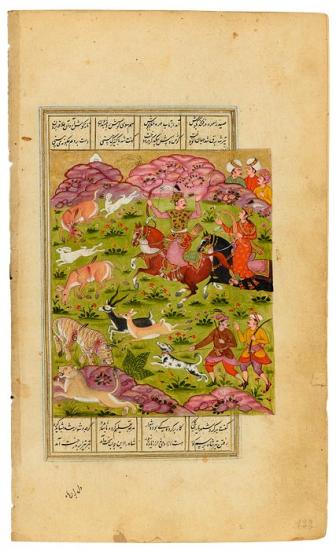

Bahrām Gūr's Trick Shot

Bahrām Gūr's Trick Shot

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, while hunting with Fitna, his harpist slave girl, Bahrām Gūr slays both a tiger and a wild ass. Unimpressed, Fitna observes that hunting is a noble pastime and that he had been trained in that art as a youth. She then challenges him to pin a wild ass's hind hoof to its ear—a trick requiring two arrows. The first grazes the animal's ear, causing it to raise its hoof to scratch it, while the second immediately pins the raised hoof to the ear. Bahrām's nickname, coincidentally, is Gūr, the Persian term for "wild ass." The trick shot is depicted at the upper left, while two hunters approach the felled lion at the lower right.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Bahrām Gūr and the Indian Princess

Bahrām Gūr and the Indian Princess Fūrak in the Black Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Saturday, the day of Saturn, dressed in black, Bahrām Gūr visits the Black Pavilion. During the day, in the darkness of the Black Pavilion, he enjoys the charms of Fūrak. When night falls—note the moon and stars—Fūrak tells the following story.

A king visited the City of the Stupefied, where all wore black, but nobody would tell him why. A bird transported him from the top of a tower to a garden. When night fell lovely maidens entered the garden, followed by the queen of the magical creatures, whom he tried to seduce. After thirty attempts he resorted to force, and found himself returned to the bottom of the tower. He then understood why all wore black and henceforth did as well.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

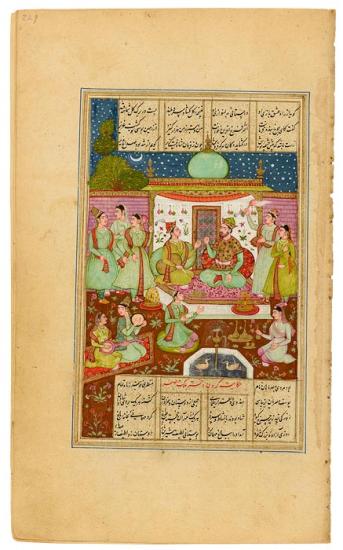

Bahrām Gūr and Princess Azargūn

Bahrām Gūr and Princess Azargūn of Maghrib in the Turquoise Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Wednesday, the day of Mercury, dressed in turquoise, Ażargūn tells her story.

Mahan, a handsome Egyptian youth, somewhat drunk, was met by a merchant offering him a share of his treasures. Mahan ran after him and ended up in a desolate place. After meeting more demons, he found himself in a garden where he agreed to spend the night in a sandalwood tree, but descended in order to feast with a beautiful queen who turned into a beast. Mahan wept in remorse at having given in to worldly temptations. God then sent Khiżr to save him. When Mahan awoke and went home, he found his friends, who had assumed he was dead, in blue mourning clothes.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

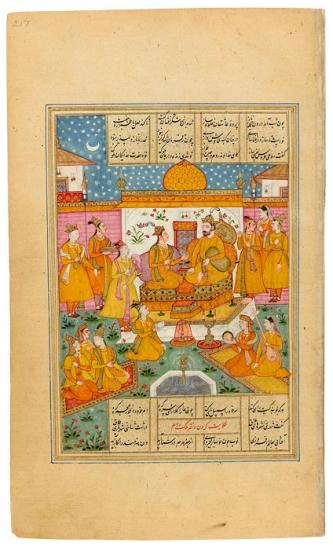

Bahrām Gūr and the Byzantine Princess

Bahrām Gūr and the Byzantine Princess Humāy in the Yellow Pavillion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Sunday, the day of the Sun, everybody is dressed in yellow. As evening approaches Humāy is asked to tell her story.

A king's horoscope told of the constant strife of marriage, so he bought slave girls instead. One day, however, he acquired a rare beauty, knowing that she refused to share her favors. Though they lived in harmony, he wished to learn why. She then explained she feared death because all her clanswomen had died during childbirth. He then loved her all the more because of her truthfulness. An evil old woman, who did not want the king to find happiness, then urged him to make her jealous, assuming the king would fall in love with the new slave girl she procured. But the evil plan failed, for his truthful slave admitted her love and yielded to a happy union.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Bahrām Gūr and the Chinese Princess

Bahrām Gūr and the Chinese Princess Yaghmānāz in the Sandalwood Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Thursday, the day of Jupiter, Bahrām visits the Chinese princess in her sandalwood pavilion and hears her story.

There were two desert travelers named Good and Evil. When Evil stole Good's water, he forced Good to give up his possessions and eyesight in order to regain it. But Good was saved by a Kurd, whose pulp from sandalwood leaves restored sight and healed epilepsy. After marrying the Kurd's daughter, Good used the leaves to cure the king's daughter of epilepsy, and she became his second wife. When he cured the vizier's blind daughter, he gained yet another wife. Good sometimes returned to the desert to savor the scent of sandalwood and always dressed in the color of its bark.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

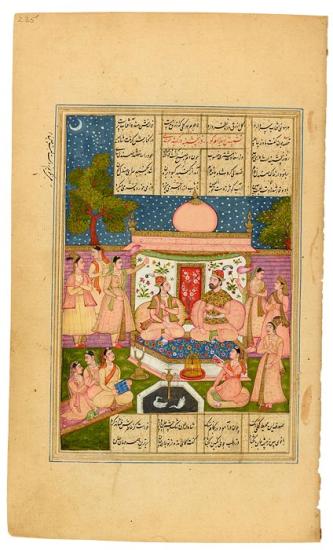

Bahrām Gūr and the Persian Princess

Bahrām Gūr and the Persian Princess Dursitī in the White Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

Since Friday is Venus's day, Bahrām wonders whether his seventh bride, having come from his own kingdom, will be the sweetest of all. Her story was passed down by her mother.

A handsome young owner of a garden surprised some women who were feasting in it. After determining that he was not a thief, they hid him, helping him to win the beauty of his choice. After his attempts at consummation were frustrated (the tree nook's floor collapsed, the tree branches broke, and a wolf chased foxes through the garden—all bad omens), he finally realized that the desired result could be obtained only through marriage.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

One day, in his castle in Khavarnak, Bahrām Gūr comes across a secret room that had been overlooked by his keeper. After entering the room he sees portraits of seven princesses with whom he instantly falls in love. Among the portraits was one of a young man inscribed with his name, an omen of things to come. After receiving permission from their fathers, he marries them all, building for each a domed pavilion with a color scheme symbolizing the country from which each came. The colors also symbolize the days of the week and the planets for which they were named. Each princess is asked to tell a sensuous story matching the mood of the color. "Even as the planets move, so then shall I," says Bahrām, and "I will visit one pavilion a day from the first of the week to the last." He apparently followed the cycle for at least seven years.

Persian poetry

The Persians loved their poetry and their poets, though the Qur˒an warned against believing their words (sura 69.41) and "those straying in evil who follow them" (sura 26.224). While Arabic was the first language of Islam and the language of the Qur˒an, Persian was favored by poets. Even Firdausī's (940–1020) celebrated Shāhnāma (Book of Kings), the national epic of Persian, was written in verse—some 50,000 couplets! Rūmī (1207–1273), the best known of the Sufi poets, put poetry in perspective when he wrote, "A hundred thousand books of poetry existed / Before the word of the illiterate [Prophet] they were put to shame!" (Masnavī I, 529). Presented here are illustrations of Firdausī's Shāhnāma as well as works by Sa˓ dī (ca.1184–1292), Hāfiz (ca. 1320–1389), and Jāmī (1414–1492), regarded as the last of the great Sufi poets. Also featured are illustrations from each of the five poems of the Khamsa (Quintet), by Niẓāmī (ca. 1141–1209), especially Lailā and Majnūn (The Persian Romeo and Juliet) and Bahrām Gūr's Seven Princesses.

Bahrām Gūr and the Slavic Princess

Bahrām Gūr and the Slavic and the Slavic Princess Nasrīnnosh in the Red Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Tuesday, the day of Mars, dressed in red, Bahrām Gūr visits the Red Pavilion. Bahrām, whose name is the Persian term for "Mars," is in his own domain as Nasrīnnosh tells her story.

In Russia there lived a princess so beautiful and learned that she was unable to find an equal. She agreed to accept a suitor who was of noble descent, able to disarm the talismans, find entry to her fortress, and solve four riddles. Those who failed were beheaded. One young suitor, however, with the help of an old man, won the prize and thereafter dressed in red.

The story became the prototype for Puccini's opera, Turandot, a popular name for girls in the Near East.

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Tuesday, the day of Mars, dressed in red, Bahrām Gūr visits the Red Pavilion. Bahrām, whose name is the Persian term for "Mars," is in his own domain as Nasrīnnosh tells her story.

In Russia there lived a princess so beautiful and learned that she was unable to find an equal. She agreed to accept a suitor who was of noble descent, able to disarm the talismans, find entry to her fortress, and solve four riddles. Those who failed were beheaded. One young suitor, however, with the help of an old man, won the prize and thereafter dressed in red.

The story became the prototype for Puccini's opera, Turandot, a popular name for girls in the Near East.

Bahrām Gūr and the Tartar Princess

Bahrām Gūr and the Tartar Princess and the Tartar Princess Nāzpāri in the Green Pavilion

Khamsa (Quintet), in Persian, written by Mullā Fatḥ Muḥammad

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.

On Monday, the day of the Moon, Bahrām Gūr, dressed in green, asks Nāzpāri for a story.

Good Bāshr, of the country of Rum, loved his books above women but was smitten by a beautiful woman whose face was revealed when a wind lifted her veil. Unable to open his books and forget her, he made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. On the way back, he was joined by evil Malikha, a know-it-all. Not realizing a large vessel with a ceramic rim was a well, Malikha bathed in it and drowned. Bāshr buried him, gathered his valuables, and took them to Malikha's wife. When she lifted her veil, Bāshr recognized the face that had been revealed by the wind. With the wicked husband dead, the good Bāshr joyfully married his widow.

The Seven Princesses

This episode appears in the Haft Paikar (Seven Princesses), the last part (1197) of the Persian poet Niẓāmī's Khamsa (Quintet). It is essentially a romanticized biography of Bahrām Gūr, a Persian king (r. 421–438) and a renowned hunter and lover.