Mark Twain: A Skeptic's Progress

Samuel L. Clemens was born on November 30, 1835. He adopted the pseudonym Mark Twain in 1863, working as a newspaper reporter on the American frontier. Twain's career as travel writer, lecturer, novelist, short story writer, fabulist, and social commentator brought him immense fame and made him "the most conspicuous person on the planet" by the time of his death in 1910.

To celebrate the 175th anniversary of his birth, The Morgan Library & Museum, in partnership with The New York Public Library, presents the iconic author's manuscripts, letters, drawings, books, original illustrations for his books, and posed and candid photographs. These works convey the essence of Twain's acerbic humor and philosophy and explore a central, recurring theme throughout his work—an uneasy, often critical, attitude toward a rapidly modernizing America.

This online presentation includes a selection of works from the exhibition.

This exhibition is generously supported by the Margaret T. Morris Fund for Americana and Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey C. Walker, with additional assistance from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, The Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation, and the F. M. Kirby Foundation.

Photograph of Mark Twain, dated 1904 (taken the day he buried his wife) taken by Isabel Lyon. The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Overview

Pudd'nhead Wilson

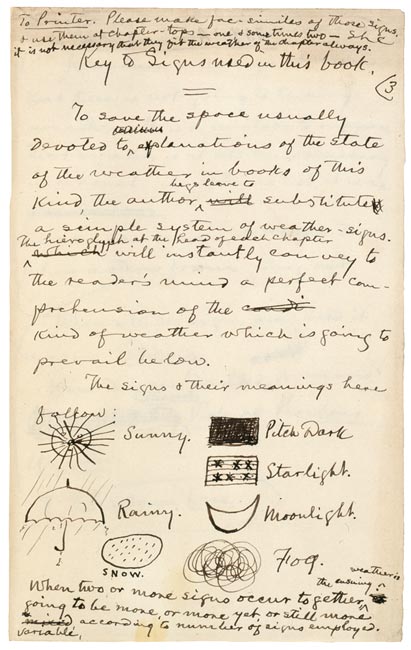

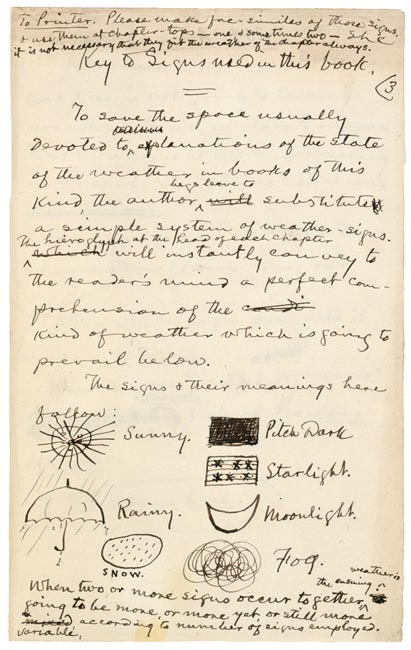

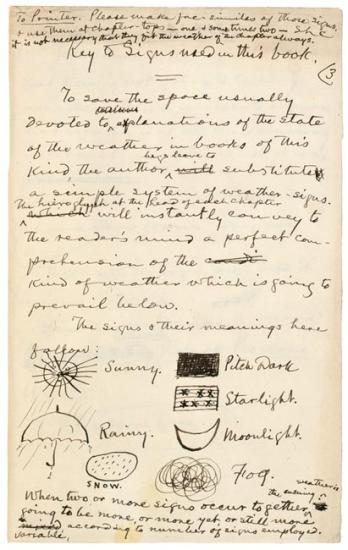

Autograph manuscript of Pudd'nhead Wilson, 1893

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Twain wrote Pudd'nhead Wilson in a blaze of creativity, spurred by his imminent bankruptcy. The finances of Twain's publishing firm, Webster and Company, were failing, and his continued investment in the Paige typesetting machine was becoming overwhelming. He needed to write a commercially successful novel quickly and completed 60,000 words between November 12 and December 14 1892. Making light of his haste, Twain used seven symbols to denote weather conditions and instructed the printer to insert them at the head of each chapter. They do not appear in the printed edition. When Twain finished the novel in July 1893, he told Fred Hall that "there ain't any weather in it, & there ain't any scenery—the story is stripped for flight!"

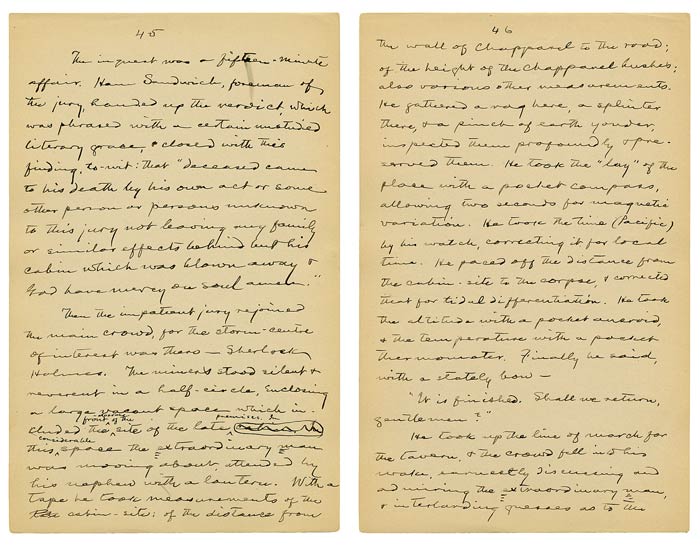

A Double-Barrelled Detective Story

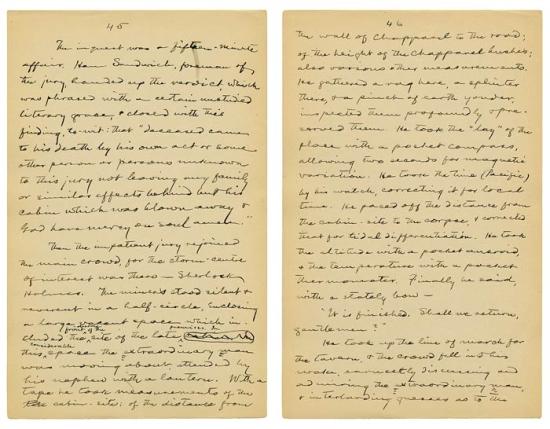

Autograph manuscript of "A Double-Barrelled Detective Story," 1901

Pages 45 and 46

Purchased on the Fellows Fund, 1977

Twain was skeptical—and scathing—about the capabilities and techniques of both the police and private detectives, such as Allan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Nevertheless, he was fascinated by the possibilities created by scientific knowledge and methods in the solving of crime and wrote stories intended to capitalize on the popularity of detective fiction as a genre. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories achieved enormous popularity, and Twain, perhaps antagonized by Doyle's public defense of the Boer War, elaborately burlesqued the scientific methods of Doyle's most famous fictional creation in "A Double-Barrelled Detective Story." Holmes "took the 'lay' of the place with a pocket compass, allowing two seconds for magnetic variation. . . . He took the altitude with a pocket aneroid, & the temperature with a pocket thermometer."

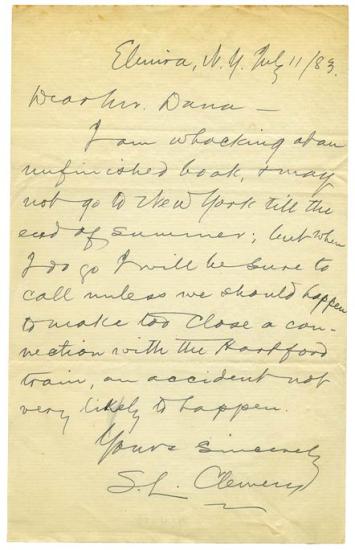

Letter to Dana

Autograph letter signed, dated Elmira, New York, July 11 1883, to [Charles Anderson] Dana

Purchased on the Acquisitions Fund, 1987

Twain told Charles A. Dana, editor of The Sun newspaper, that he was putting off his planned trip to New York because "I am whacking at an unfinished book." The book was his masterpiece, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which he had begun in the summer of 1876, shortly after finishing The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Composition of Huckleberry Finn had twice stalled, and Twain even considered burning the manuscript before returning to work on it with renewed energy in the summer of 1883. His spring of 1882 steamboat journey through the Mississippi River valley supplied the creative impetus he needed to write Life on the Mississippi (1883) and to finish Huckleberry Finn.

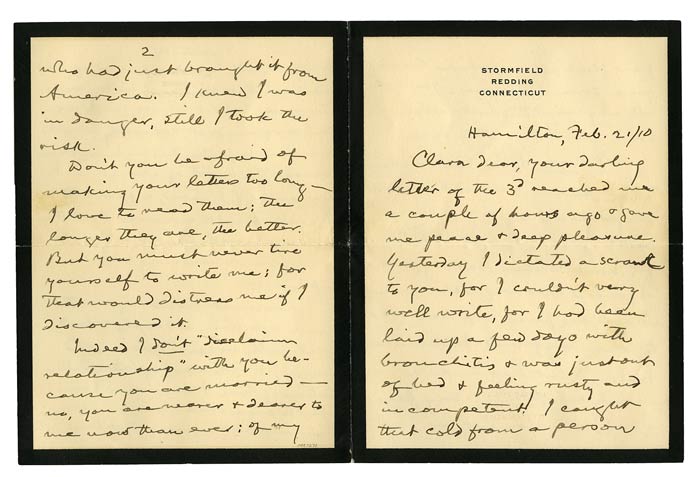

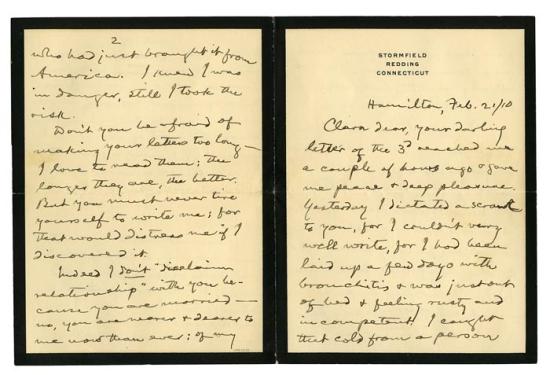

Letter to Clara Clemens, pages 1–2

Autograph letter signed, dated Hamilton, Bermuda, February 21–23 1910, to Mrs. Ossip Gabrilowitsch [Clara Clemens]

Purchased on the John F. Fleming Fund, 2008

In January 1910, following the death of his daughter Jean the previous month, Twain returned to Bermuda and stayed until April 12 . This revealing, outspoken, and poignant eight-page letter to Clara, his only surviving daughter, was written over three days only two months before his own death. He told her that he would not appeal to his friend, Archbishop Ireland, to seek Easter privileges at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome because "I can't bring myself to personally ask a favor of that odious Church, whose history would disgrace hell, & whose birth was the profoundest calamity which has ever befallen the human race except the birth of Christ." The end of the letter concerns Twain's unpublished autobiography, about which he reassured Clara that "I'm not going to 'bury you alive.'"

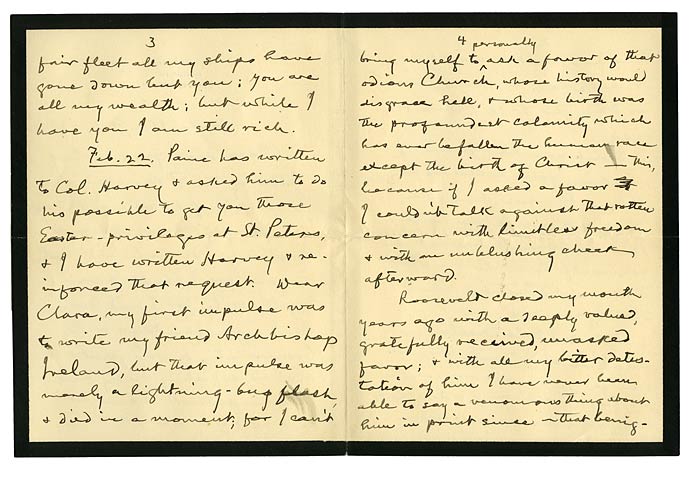

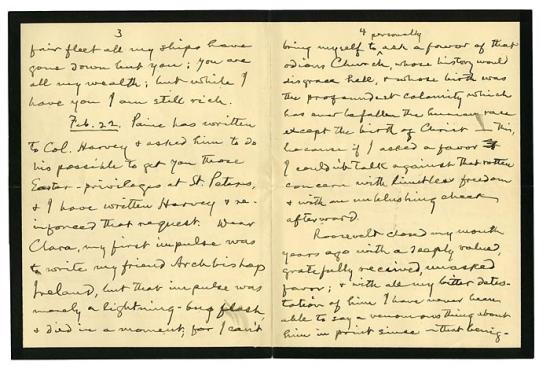

Letter to Clara Clemens, pages 3–4

Autograph letter signed, dated Hamilton, Bermuda, February 21–23 1910, to Mrs. Ossip Gabrilowitsch [Clara Clemens]

Purchased on the John F. Fleming Fund, 2008

In January 1910, following the death of his daughter Jean the previous month, Twain returned to Bermuda and stayed until April 12 . This revealing, outspoken, and poignant eight-page letter to Clara, his only surviving daughter, was written over three days only two months before his own death. He told her that he would not appeal to his friend, Archbishop Ireland, to seek Easter privileges at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome because "I can't bring myself to personally ask a favor of that odious Church, whose history would disgrace hell, & whose birth was the profoundest calamity which has ever befallen the human race except the birth of Christ." The end of the letter concerns Twain's unpublished autobiography, about which he reassured Clara that "I'm not going to 'bury you alive.'"

Letter to Clara Clemens, pages 5–6

Autograph letter signed, dated Hamilton, Bermuda, February 21–23 1910, to Mrs. Ossip Gabrilowitsch [Clara Clemens]

Purchased on the John F. Fleming Fund, 2008

In January 1910, following the death of his daughter Jean the previous month, Twain returned to Bermuda and stayed until April 12 . This revealing, outspoken, and poignant eight-page letter to Clara, his only surviving daughter, was written over three days only two months before his own death. He told her that he would not appeal to his friend, Archbishop Ireland, to seek Easter privileges at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome because "I can't bring myself to personally ask a favor of that odious Church, whose history would disgrace hell, & whose birth was the profoundest calamity which has ever befallen the human race except the birth of Christ." The end of the letter concerns Twain's unpublished autobiography, about which he reassured Clara that "I'm not going to 'bury you alive.'"

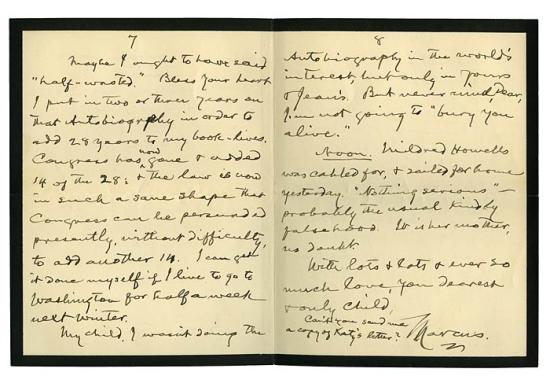

Letter to Clara Clemens, pages 7–8

Autograph letter signed, dated Hamilton, Bermuda, February 21–23 1910, to Mrs. Ossip Gabrilowitsch [Clara Clemens]

Purchased on the John F. Fleming Fund, 2008

In January 1910, following the death of his daughter Jean the previous month, Twain returned to Bermuda and stayed until April 12 . This revealing, outspoken, and poignant eight-page letter to Clara, his only surviving daughter, was written over three days only two months before his own death. He told her that he would not appeal to his friend, Archbishop Ireland, to seek Easter privileges at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome because "I can't bring myself to personally ask a favor of that odious Church, whose history would disgrace hell, & whose birth was the profoundest calamity which has ever befallen the human race except the birth of Christ." The end of the letter concerns Twain's unpublished autobiography, about which he reassured Clara that "I'm not going to 'bury you alive.'"

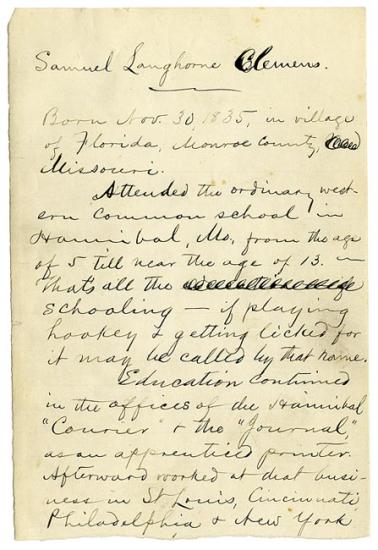

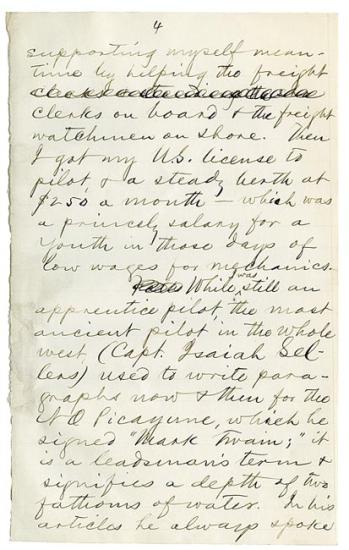

Autobiographical notes, page 1

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

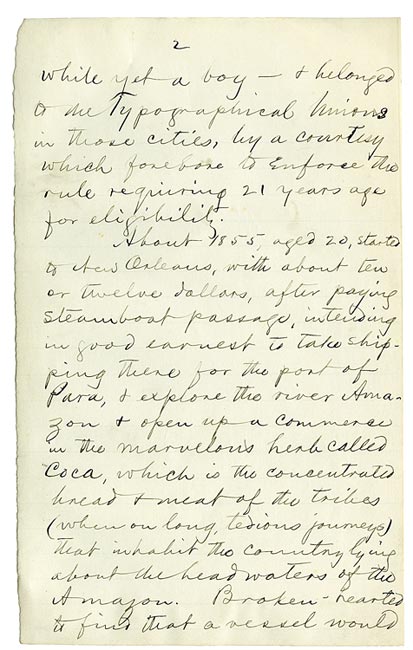

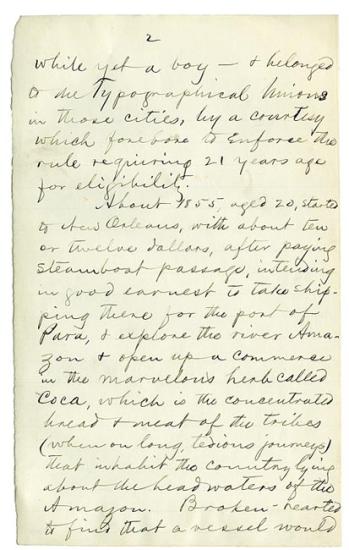

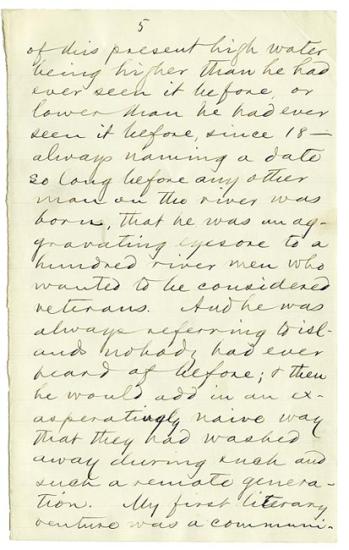

Autobiographical notes, page 2

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

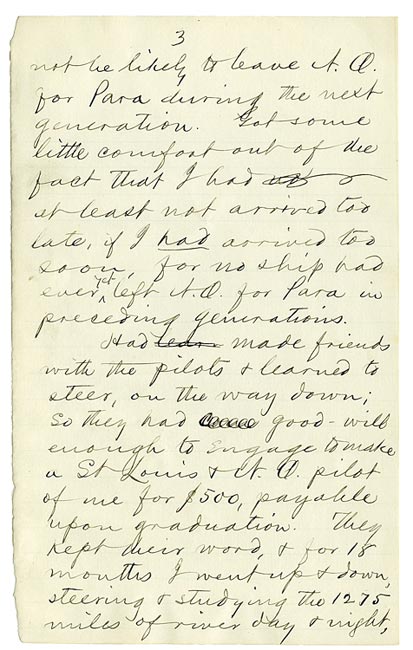

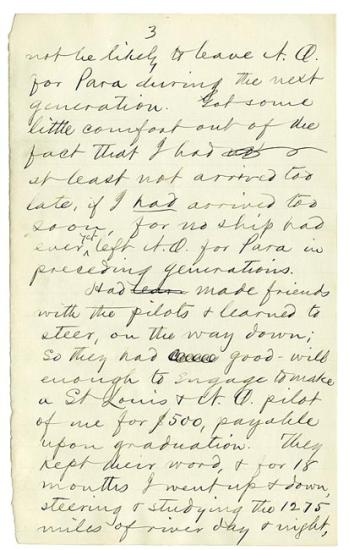

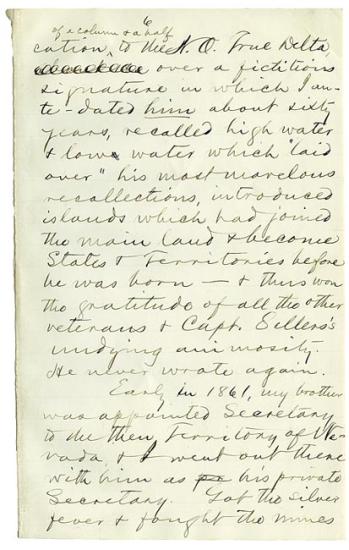

Autobiographical notes, page 3

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

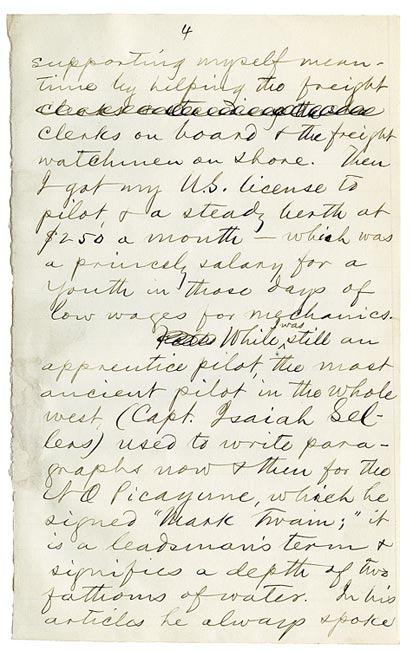

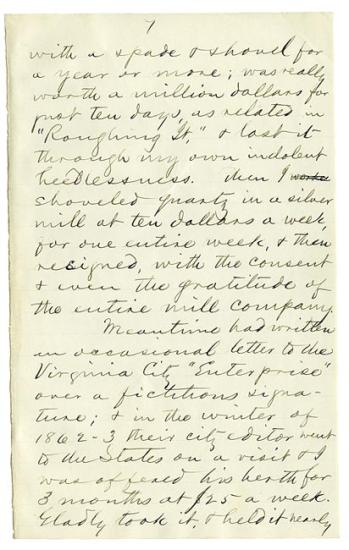

Autobiographical notes, page 4

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

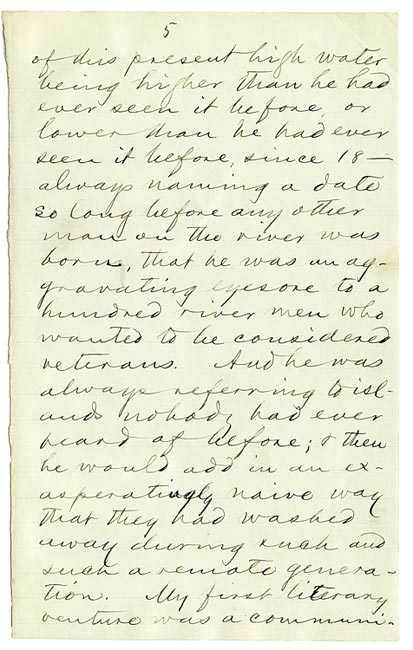

Autobiographical notes, page 5

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

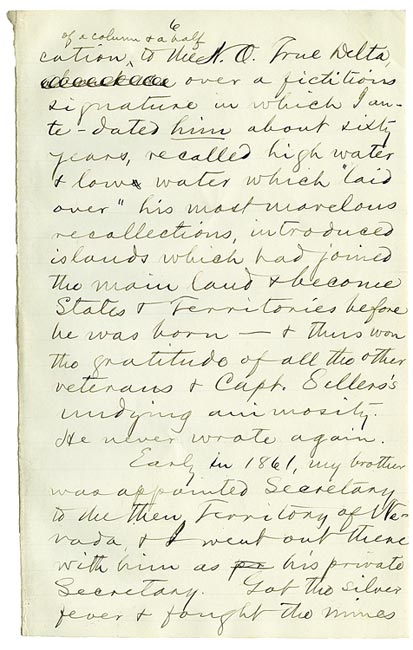

Autobiographical notes, page 6

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

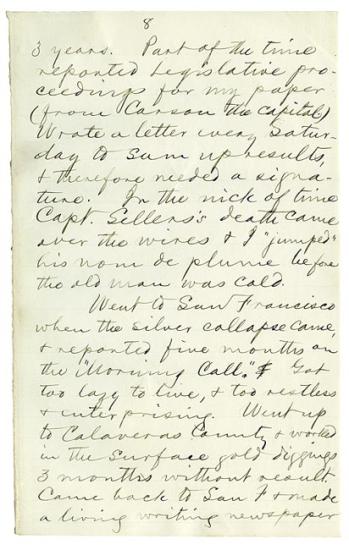

Autobiographical notes, page 7

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

Autobiographical notes, page 8

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

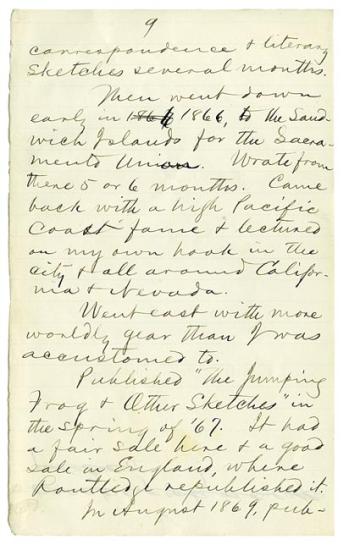

Autobiographical notes, page 9

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

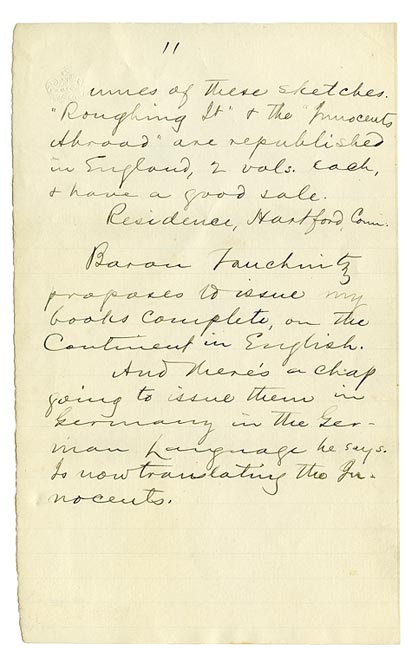

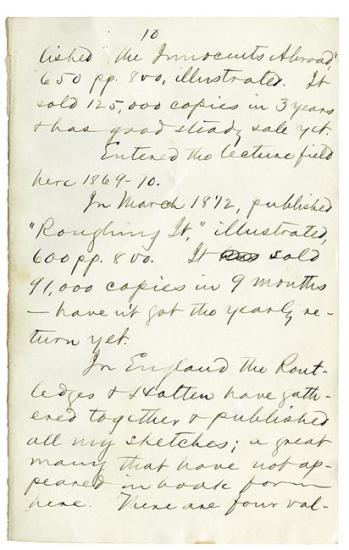

Autobiographical notes, page 10

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

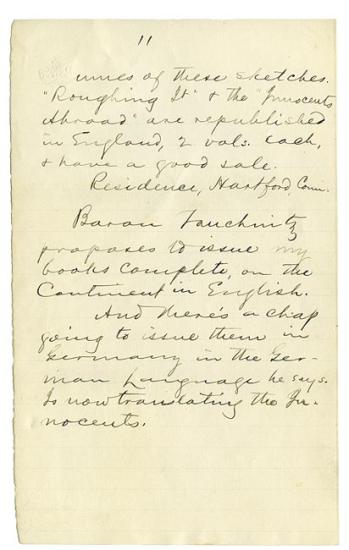

Autobiographical notes, page 11

Autograph autobiographical notes signed, [Hartford], [late January or early February 1873]

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910

This is the first known account of the origin of the nom de plume "Mark Twain." It was written for Charles Dudley Warner, Twain's Hartford neighbor, with whom he collaborated on writing The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). This eleven-page manuscript accounts for Twain's life from birth until the publication of Roughing It in 1872 and includes this section on his apprenticeship as a riverboat pilot. He noted that the pen name Mark Twain had been used by "the most ancient pilot in the whole west (Capt. Isaiah Sellers). . . . Mark Twain is a leadsman's term & signifies a depth of two fathoms of water." When Twain learned of Sellers's death, he "'jumped' his nom de plume before the old man was cold."

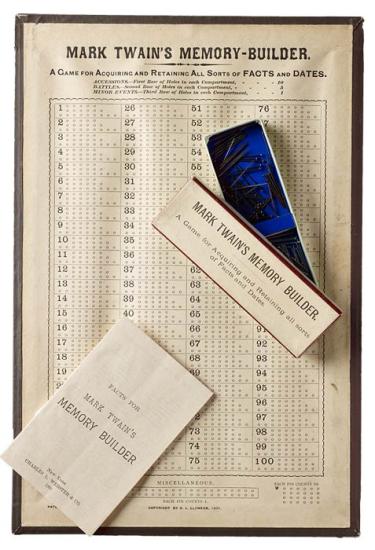

Memory-Builder

Mark Twain's Memory-Builder: a game for acquiring and retaining all sorts of facts and dates: the original three piece game / written and designed by Mark Twain. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1891.

Gift of Miss Julia P. Wightman, 1991

By the nineteenth century, invention as a means of progress had become deeply rooted in the American consciousness, and individual entrepreneurial inventors were akin to folk heroes. Twain enjoyed the friendship of Thomas Edison, who recorded the author's voice on a wax cylinder and his image with a motion picture camera. Twain nurtured aspirations as an inventor and secured patents on a diverse range of products, including a self-pasting scrapbook, a perpetual calendar, a notebook with tear-away tabs, a self-adjusting garter, and this game. Only the scrapbook ever turned a profit, bringing him $50,000. Memory-Builder was a commercial disaster, though not on the scale of the Paige typesetter, in which Twain continued to invest until it brought about his bankruptcy in 1894.

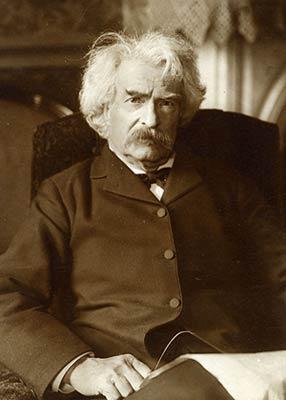

Otto J. Schneider portrait

Otto J. Schneider portrait

Purchased for the Dannie and Hettie Heineman collection as the gift of the Heineman Foundation, 2010

Schneider has been praised for the "direct and virile characterization" of his portraiture, which revealed "the most characteristic, most essential thing in the personality of his subject." His 1906 half-length portrait of Twain, after a photograph by J. G. Gessford and drawings from life, portrays the author at the height of his fame. Staring intensely at the viewer, Twain is defiant and skeptical. Twain was quick to adopt new technologies, such as photography, and became one of the most famous and immediately recognizable individuals of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century America, through his use of widely published photographic portraits to cultivate and sustain his public image. He was at the forefront of the modern cult of celebrity, presenting himself as iconoclast and sage.

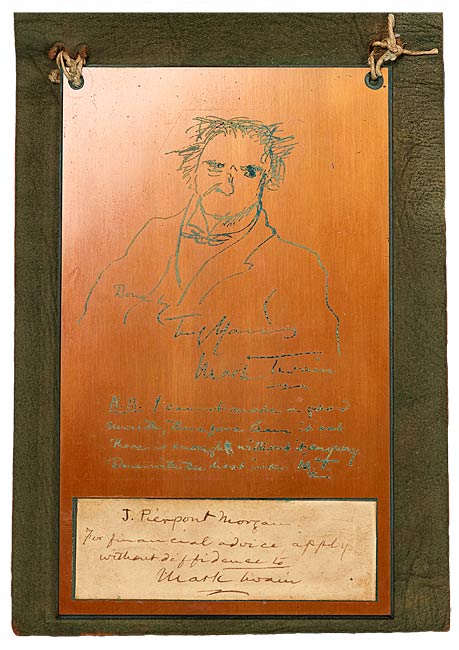

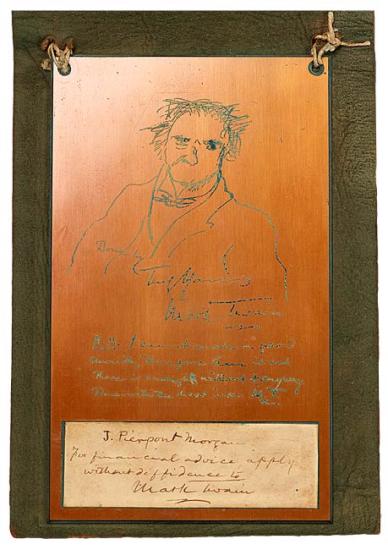

Self-Caricature

Self-Caricature

Gift of Mark Twain, 1902

This self-caricature, engraved on a copperplate, is signed Done by / Truly Yours / Mark Twain. It was one of the souvenirs presented to each of the guests at the dinner honoring Twain on his sixty-seventh birthday, November 28, 1902, at the Metropolitan Club, New York. The engraved note reads: "N.B. I cannot make a good / mouth, therefore I leave it out. / There is enough without it anyway. / Done with the best ink. M.T." It is housed in a brown leather case and lettered Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan in gilt. To further personalize these facsimile engravings, a slip of paper was inset below the image, with a characteristically ironic handwritten note to the recipient from Twain: J. Pierpont Morgan. For financial advice apply without diffidence to Mark Twain.

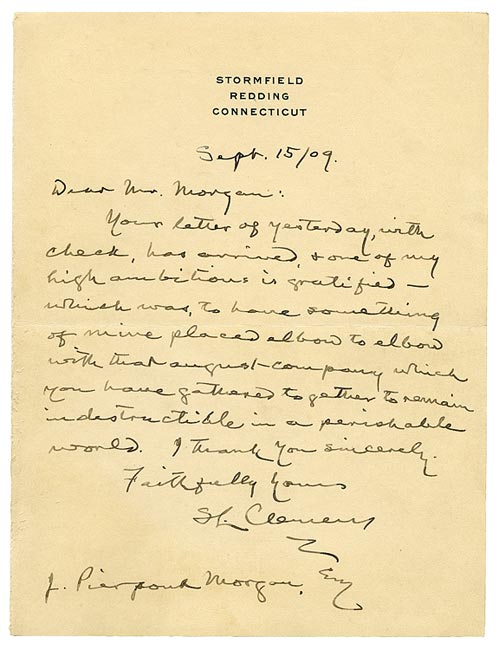

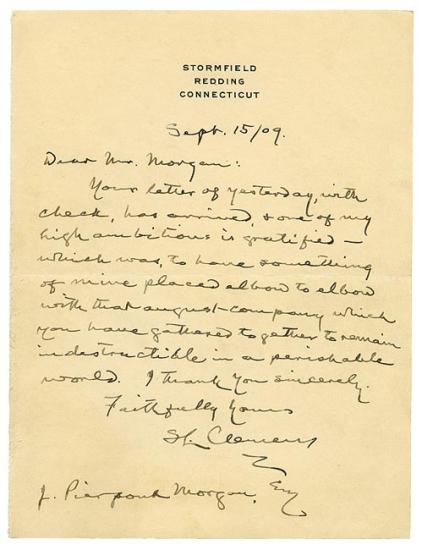

Letter to Pierpont Morgan

Autograph letter signed, dated Redding, Connecticut, September 15, 1909, to Pierpont Morgan

Acquired by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Pierpont Morgan purchased Twain's autograph manuscripts of Life on the Mississippi and Pudd'nhead Wilson directly from the author in 1909. Twain had become a friend of the Morgan family and was an occasional visitor to Pierpont Morgan's library, according to Morgan's librarian, Belle da Costa Greene. When Twain wrote to thank Morgan for purchasing the manuscripts, he told him that "one of my high ambitions is gratified—which was, to have something of mine placed elbow to elbow with that august company which you have gathered together to remain indestructible in a perishable world." Morgan paid Twain an "honorarium" of $2,500 for the manuscripts and declared himself to be "delighted with them."

Photographs

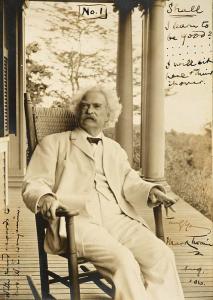

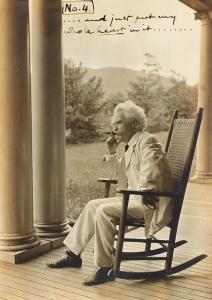

Albert Bigelow Paine (1861–1937)

Purchased on the John F. Fleming Fund, 2008; MA 7253

In this series of seven photographs, taken in 1906, the author relaxes in a rocking chair on a porch in Dublin, New Hampshire, smoking a cigar. Twain's accompanying note explained that the series "registers with scientific precision, stage by stage, the progress of a moral purpose through the mind of the human race's Oldest Friend." To further explicate his thought process, Twain inscribed each print with a continuous caption, which concludes with mock self-contentment: "Oh, never mind, I reckon I'm good enough just as I am." He sent them to his friend Mrs. Benjamin and joked that this "series of moral photographs" could be displayed in her daughter's bedroom to provide moral instruction. These photographs are a vivid example of Twain's playful and humorous public persona.

Mark Twain

Autograph manuscript of Pudd'nhead Wilson, 1893

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1909

Twain wrote Pudd'nhead Wilson in a blaze of creativity, spurred by his imminent bankruptcy. The finances of Twain's publishing firm, Webster and Company, were failing, and his continued investment in the Paige typesetting machine was becoming overwhelming. He needed to write a commercially successful novel quickly and completed 60,000 words between November 12 and December 14 1892. Making light of his haste, Twain used seven symbols to denote weather conditions and instructed the printer to insert them at the head of each chapter. They do not appear in the printed edition. When Twain finished the novel in July 1893, he told Fred Hall that "there ain't any weather in it, & there ain't any scenery—the story is stripped for flight!"