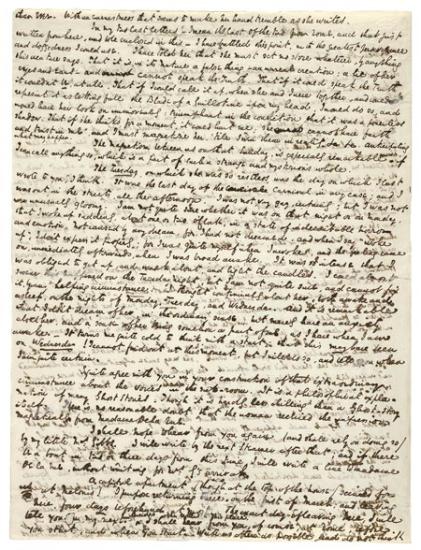

Letter 15 | 10 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 1

Autograph letter signed, Naples, 10 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Dickens's letters to Emile de la Rue included progress reports on the positive effects of his mesmeric treatment of Madame de la Rue, which was no less fervent for being, by this stage, conducted in absentia. Utterly confident in his powers, Dickens told de la Rue that, "when I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize [hypnotize] a Frying-Pan." The biographer Fred Kaplan argued: "Mesmerism provided Dickens not only with a rationale for the working of personality and mind . . . but with a language and an imagery that could be dramatically utilized in fictional creation." But Peter Ackroyd has suggested that for Dickens mesmerism was "part of his need to control, to dominate, to manipulate."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

My Dear De la Rue.

We were delayed a day longer than I had expected, in Rome; and did not get here, until yesterday Evening. The Steamer which brought me your most welcome Packet arrived at breakfast-time this morning. I saw it coming; and had your letter in my hand, almost as soon as I had shut the telescope, through which I watched it into Port.

I am much concerned that you should think it possible I had the faintest doubt of the true depth, intensity, and earnestness, of your devotion to Madame De la Rue; or of the affectionate and zealous watch you have kept over her in all her sufferings. Believe me, I admire and feel your constancy under such a trial, scarcely less than hers; and that everything I have seen of you, in reference to her (it has been much, though in a short time) has filled me with a sorrowful pleasure, not easy of expression. When I wrote to you, strongly, on the Great and terrible symptom which is hovering about her, and over which—God be thanked for it!—we know we can exercise great power; I wrote as I felt. As I felt, do I say! Not one twentieth part as strongly as I felt, and feel. For the mystery of her mind in connexion with this Phantom, was then just opening to me. And the vast extent of the danger by which I saw she was beset, made me clench the pen as if it were an iron rod—Made me use it too, as clumsily as if it were a poker, when it became the instrument of conveying such a wrong and groundless idea to you.

My full reasons for entertaining this fervid opinion of the necessity of following up the blow that has been struck at this worst symptom of her state, I cannot give you. For she makes a condition with me that I shall not, until—she looks forward, you see, to being quite composed upon the subject, one day—until she gives me leave. Under the impression that with all your anxious care you might not know what she had kept hidden so fearfully in her breast, I wrote as I did. With no other grain of meaning or intention my dear friend, believe me.

I think it possible, even now—I think it probable, indeed—that as the time approaches for your journey to Rome, she may raise objections, and be disinclined to go. The more she shews this state of mind, the greater the danger is, and the more urgent and imperative the necessity for her being brought—I underline the word "brought" to express—by your determination. You feel with me, I know.

Observe, my dear De la Rue. On Sunday the Second, she confesses to you that she feels stronger against the figures, now that the journey is decided on. That night, she sees the Figure, and apparently overcomes it. But before it disappears, it says something, which she does not distinctly hear. On the next day, she vaguely damps the ardour of your preparations for the journey. I strongly incline, with you, to the belief that trying in the interval to put together what scattered words she heard the figure say, she joined and dovetailed them into some threat, having reference to her venturing to undertake the journey. And I think you will always find that her otherwise unaccountable indisposition to go, manifests itself, after an interview with this Phantom. That her own heart is set on going—that her whole being is full of the most earnest hope and expectation of relief that all her wishes tend that way—I know. In this very last letter, received to day, she speaks of it with greater Earnestness than

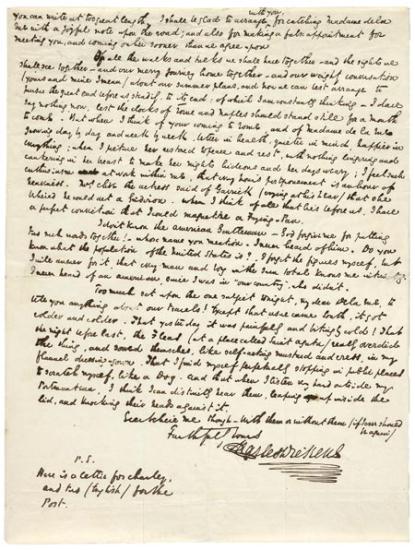

Letter 15 | 10 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 2

Autograph letter signed, Naples, 10 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Dickens's letters to Emile de la Rue included progress reports on the positive effects of his mesmeric treatment of Madame de la Rue, which was no less fervent for being, by this stage, conducted in absentia. Utterly confident in his powers, Dickens told de la Rue that, "when I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize [hypnotize] a Frying-Pan." The biographer Fred Kaplan argued: "Mesmerism provided Dickens not only with a rationale for the working of personality and mind . . . but with a language and an imagery that could be dramatically utilized in fictional creation." But Peter Ackroyd has suggested that for Dickens mesmerism was "part of his need to control, to dominate, to manipulate."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

than ever. With an earnestness that seems to make her hand tremble as she writes.

In my two last letters—I mean the last of the two from Rome, and that just written from here, and to be enclosed in this—I have battled this point, with the greatest perseverance and doggedness I could use. I have told her that she must set no store whatever, by anything this creature says. That it is in its Nature a false thing—an unreal creation; a lie of her eyes and Ears—and cannot speak the Truth. That if it could speak the Truth, it couldn't be, at all. That if I could call it up, when she and I were together, and could represent it as letting fall the Blade of a Guillotine upon my head, I would do so, and would have her look on immoveably: triumphant in the conviction that it was a powerless shadow. That if she thinks, for a moment, it could hurt me; she cannot have faith and trust in me, and I must magnetize her, 'till I win them in reality—&c&c. Anticipating what may happen.

The Magnetism between us on that Sunday, is especially remarkable—if I can call anything so, which is a part of such a strange and mysterious whole.

The Tuesday, on which she was so restless, was the day on which I last wrote to you, I think. It was the last day of the Carnival in any case; and I was out, in the streets, all the afternoon. I was not very gay, certainly; but I was not unusually gloomy. I am not quite sure whether it was on that night or on Monday, that I woke up suddenly, about one or two o'Clock, in a state of indescribable horror and emotion. Not caused by any dream, for I had not dreamed. And when I say "woke up", I don't express it properly; for I was quite myself when I awoke, and the feeling came on, immediately afterwards, when I was broad awake. It was so intense that I was obliged to get up, and walk about, and light the candles. I could almost swear this happened on the Tuesday Night, but I am not quite sure, and cannot fix it, by any helping circumstance. I thought continually about her, both awake and asleep, on the nights of Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. And it is remarkable that I don't dream of her, in the ordinary sense; but merely have an anxiety about her, and a sense of her being somehow a part of me, as I have when I am awake.—It turns me quite cold to think, with a start, that this may have been on Wednesday! I cannot find out at this moment, but I will do so, and tell you when I am quite certain.

I quite agree with you in your construction of that extraordinary circumstance about the voices in the sick-room. It is a philosophical explanation of many Ghost Stories. Though it is hardly less chilling than a Ghost-Story itself. There is no reasonable doubt that the woman received the impression magnetically from Madame De la Rue.

I shall hope to hear from you again (and shall rely on doing so) by my little Mrs. Gibbs. I will write by the next Steamer after that; and if there be a boat in two or three days from this time, I will write a line to Madame De la Rue, without waiting for Mrs. G's arrival.

A capital apartment (though at the top of the house) secured for us at Meloni's! I purpose returning there, on the first of March; and leaving here, four days beforehand, at most. The exact day of leaving here, I will tell you in my next. Besides other letters to this place, I shall hear from you, of course, at Rome, before you start, and when you start. Write as often as possible—and do not think

Letter 15 | 10 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 3

Autograph letter signed, Naples, 10 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Dickens's letters to Emile de la Rue included progress reports on the positive effects of his mesmeric treatment of Madame de la Rue, which was no less fervent for being, by this stage, conducted in absentia. Utterly confident in his powers, Dickens told de la Rue that, "when I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize [hypnotize] a Frying-Pan." The biographer Fred Kaplan argued: "Mesmerism provided Dickens not only with a rationale for the working of personality and mind . . . but with a language and an imagery that could be dramatically utilized in fictional creation." But Peter Ackroyd has suggested that for Dickens mesmerism was "part of his need to control, to dominate, to manipulate."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

you can write at too great length. I shall be glad to arrange with you, for catching Madame de la Rue with a joyful note, upon the road; and also for making a false appointment for meeting you, and coming on her sooner than we agree upon.

Of all the walks and talks we shall have together—and the sights we shall see together—and our merry journey home together—and our weighty conversation (yours and mine I mean) about our summer plans, and how we can best arrange to pursue the great end before us, steadily, to its end: of which I am constantly thinking—I dare say nothing, now, lest the clocks of Rome and Naples should stand still for a Month to come. But when I think of your coming to Rome, and of Madame de la Rue growing day by day and week by week, better in health, quieter in mind, happier in everything; when I picture her restored to peace and rest, with nothing lingering and cankering in her breast to make her nights hideous and her days weary; I feel such enthusiasm at work within me, that every hour's postponement is an hour of heaviness. Mrs. Clive the actress said of Garrick (crying at his Lear) that she believed he could act a Gridiron. When I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize a Frying-Pan.

I don't know the American Gentleman—God forgive me for putting two such words together!—whose name you mention. I never heard of him. Do you know what the population of the United States is?—I forget the figures myself, but I will answer for it, that every man and boy in the sum total knows me intimately. I never heard of an American, since I was in "our country", who didn't.

Too much set upon the one subject tonight, my dear De la Rue, to tell you anything about our travels! Except that as we came South, it got colder and colder. That yesterday it was painfully and bitingly cold! That the night before last, the Fleas (at a place called Saint Agata) really overdid the thing, and sowed themselves, like self-acting mustard and cress, in my flannel dressing-gown. That I find myself perpetually stopping in public places to scratch myself, like a Dog. And that when I listen very hard outside my Portmanteau, I think I can distinctly hear them, leaping up inside the lid, and knocking their heads against it.

Ever believe me though—With them or without them (if I ever should be again)

Faithfully Yours

CHARLES DICKENS

Letter 15 | 10 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 4

Autograph letter signed, Naples, 10 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Dickens's letters to Emile de la Rue included progress reports on the positive effects of his mesmeric treatment of Madame de la Rue, which was no less fervent for being, by this stage, conducted in absentia. Utterly confident in his powers, Dickens told de la Rue that, "when I think of all that lies before us, I have a perfect conviction that I could magnetize [hypnotize] a Frying-Pan." The biographer Fred Kaplan argued: "Mesmerism provided Dickens not only with a rationale for the working of personality and mind . . . but with a language and an imagery that could be dramatically utilized in fictional creation." But Peter Ackroyd has suggested that for Dickens mesmerism was "part of his need to control, to dominate, to manipulate."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.