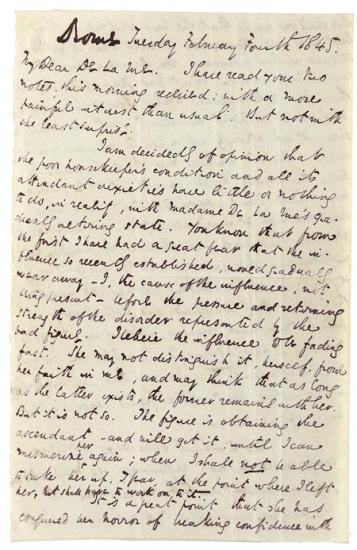

Letter 14 | 4 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 1

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

For several years prior to first meeting Dickens in 1844, Madame de la Rue had suffered from such generalized symptoms as insomnia, headaches, nervous tics, and convulsions. Over the course of his numerous mesmeric sessions, Dickens concluded that she was haunted by an evil phantom, alternately referred to in his detailed and extensive letters to her husband as "the bad figure," "Bad Spirit, "this creature," or "the shadow." Dickens came to believe that he was engaged in a powerful struggle with "this Phantom" for control of the "mind and body" of Madame de la Rue. In this letter he asserts confidence in his mesmeric abilities: "Pursuing that Magnetic power, and being near to her and with her, I believe that I can shiver it [the phantom] like Glass."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

My Dear De La Rue. I have read your two notes; this morning received; with a more painful interest than usual. But not with the least surprise.

I am decidedly of opinion that the poor housekeeper's condition and all its attendant anxieties have little or nothing to do, in reality, with Madame De La Rue's gradually altering state. You know that from the first I have had a great fear that the influence so recently established, would gradually wear away—I, the cause of the influence, not being present—before the pressure and returning strength of the disorder represented by the bad figure. I believe the influence to be fading fast. She may not distinguish it, herself, from her faith in me, and may think that as long as the latter exists, the former remains with her. But it is not so. The figure is obtaining the ascendant—and will get it, until I can mesmerize her again; when I shall not be able to take her up, I fear, at the point where I left her, but shall have to work on to it.

It is a great point that she has conquered her horror of breaking confidence with

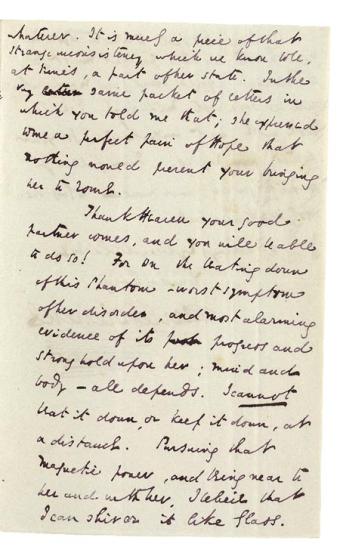

Letter 14 | 4 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 2

Autograph letter signed, Genoa, 4 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

For several years prior to first meeting Dickens in 1844, Madame de la Rue had suffered from such generalized symptoms as insomnia, headaches, nervous tics, and convulsions. Over the course of his numerous mesmeric sessions, Dickens concluded that she was haunted by an evil phantom, alternately referred to in his detailed and extensive letters to her husband as "the bad figure," "Bad Spirit, "this creature," or "the shadow." Dickens came to believe that he was engaged in a powerful struggle with "this Phantom" for control of the "mind and body" of Madame de la Rue. In this letter he asserts confidence in his mesmeric abilities: "Pursuing that Magnetic power, and being near to her and with her, I believe that I can shiver it [the phantom] like Glass."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

shadow, and that she has told me, in this last note, all it said when it broke silence in her bedroom. On the other hand, I cannot but observe that her fear of it is greater than her subservience to me. I find this exemplified in a slight incident, but one which shews it as strongly as a greater circumstance could. She had written me that she would leave the Casino Ball, exactly at One: remembering that I had appointed that hour before: and thinking it would please me. She laid great stress on this, and underlined the words. Notwithstanding this promise and her desire to keep it, her dread of the shadow becomes so great that she utterly disregards her voluntary pledge to me, and remains abroad until the morning is far advanced (as I learn from you) to escape it. I see in this, an increasing power on the part of the figure, beyond all kind of question.

As to what she says of her confidence in not requiring the Magnetism (if need were) until my return to Genoa, we can place no reliance on it

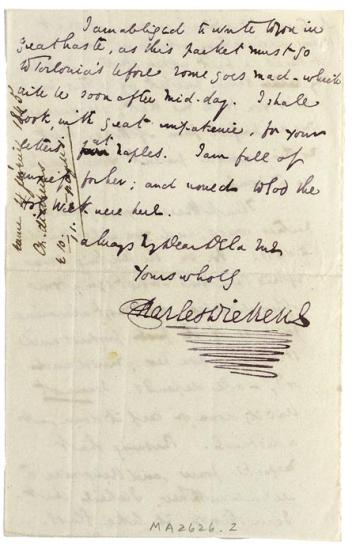

Letter 14 | 4 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 3

Autograph letter signed, Genoa, 4 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

For several years prior to first meeting Dickens in 1844, Madame de la Rue had suffered from such generalized symptoms as insomnia, headaches, nervous tics, and convulsions. Over the course of his numerous mesmeric sessions, Dickens concluded that she was haunted by an evil phantom, alternately referred to in his detailed and extensive letters to her husband as "the bad figure," "Bad Spirit, "this creature," or "the shadow." Dickens came to believe that he was engaged in a powerful struggle with "this Phantom" for control of the "mind and body" of Madame de la Rue. In this letter he asserts confidence in his mesmeric abilities: "Pursuing that Magnetic power, and being near to her and with her, I believe that I can shiver it [the phantom] like Glass."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

whatever. It is merely a piece of that strange inconsistency which we know to be, at times, a part of her state. In the very same packet of letters in which you told me that; she expressed to me a perfect pain of Hope that nothing would prevent your bringing her to Rome.

Thank Heaven your good partner comes, and you will be able to do so! For on the beating down of this Phantom—worst symptom of her disorder, and most alarming evidence of its progress and strong hold upon her; mind and body—all depends. I cannot beat it down, or keep it down, at a distance. Pursuing that Magnetic power, and being near to her and with her, I believe that I can shiver it like Glass.

Letter 14 | 4 February 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 4

Autograph letter signed, Genoa, 4 February 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

For several years prior to first meeting Dickens in 1844, Madame de la Rue had suffered from such generalized symptoms as insomnia, headaches, nervous tics, and convulsions. Over the course of his numerous mesmeric sessions, Dickens concluded that she was haunted by an evil phantom, alternately referred to in his detailed and extensive letters to her husband as "the bad figure," "Bad Spirit, "this creature," or "the shadow." Dickens came to believe that he was engaged in a powerful struggle with "this Phantom" for control of the "mind and body" of Madame de la Rue. In this letter he asserts confidence in his mesmeric abilities: "Pursuing that Magnetic power, and being near to her and with her, I believe that I can shiver it [the phantom] like Glass."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

I am obliged to write to you in great haste, as this packet must go to Torlonia's before Rome goes mad—which will be soon after Mid-day. I shall look, with great impatience, for your letters at Naples. I am full of anxiety for her; and would to God the Holy Week were here.

Always My Dear De la Rue | Yours wholly

CHARLES DICKENS