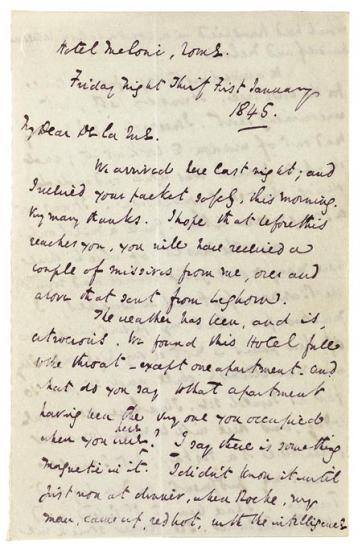

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 1

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

My Dear De la Rue.

We arrived here last night; and I received your packet safely, this morning. Very many thanks. I hope that before this reaches you, you will have received a couple of missives from me, over and above that sent from Leghorn.

The weather has been, and is, atrocious. We found this Hotel full to the throat —except one apartment. And what do you say to that apartment having been the very one you occupied when you were here? I say there is something Magnetic in it. I didn't know it until just now at dinner, when Roche, my man, came up, red hot, with the intelligence

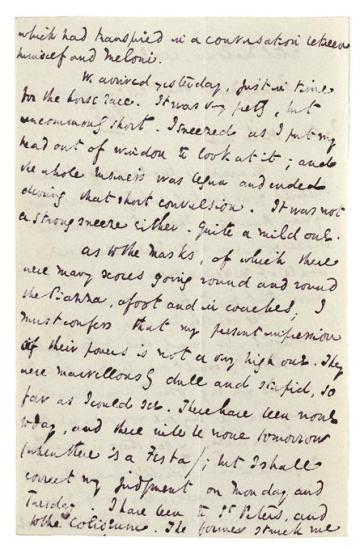

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 2

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

which had transpired in a conversation between himself and Meloni.

We arrived yesterday, just in time for the horse Race. It was very pretty, but uncommonly short. I sneezed as I put my head out of window to look at it; and the whole business was begun and ended during that short convulsion. It was not a strong sneeze either. Quite a mild one.

As to the Masks, of which there were many scores going round and round the Piazza, afoot and in coaches; I must confess that my present impression of their powers is not a very high one. They were marvellously dull and stupid, so far as I could see. There have been none today, and there will be none tomorrow (when there is a Festa); but I shall correct my judgment on Monday and Tuesday. I have been to St. Peters, and to the Coliseum. The former struck me

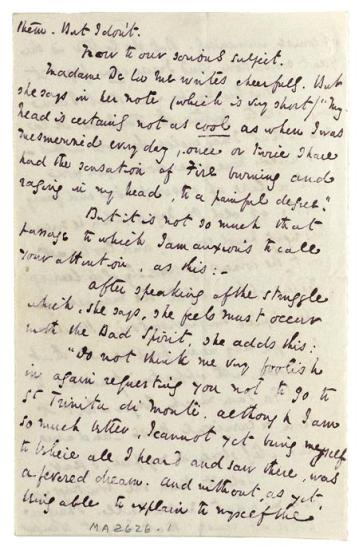

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 3

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

immensely. But the latter is the great sensation. And I never can forget it.

It is lucky for you that I am going to write forthwith to Madame De la Rue—that I may enclose the note in this—or I would have come down upon you with a blaze of description and fancy, worthy of old Di Negro, when he screws his right hand round, and looks out at the corners of those sly old leering Peepers of his, after the manner of the inspired Improvisatori. Heaven send you may never find me in that humour, with opportunity added to it! For I am much longer about it than a Carnival Horse—and am infinitely slower in my pace, I fear.

I don't know the Writings you ask me about. Not at all. I have a kind of sense that I ought to know

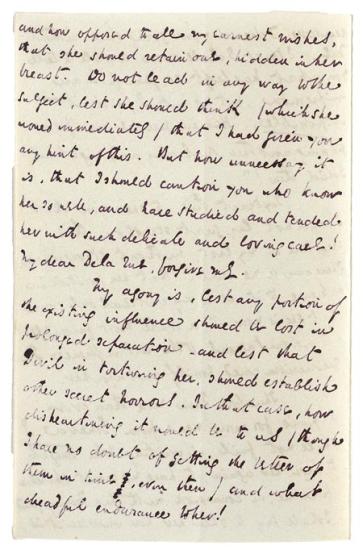

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 4

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

them. But I don't.

Now to our serious subject.

Madame De la Rue writes cheerfully. But she says in her note (which is very short) "My head is certainly not as cool as when I was mesmerized every day,—once or twice I have had the sensation of Fire burning and raging in my head, to a painful degree."

But it is not so much that passage to which I am anxious to call your attention, as this:—

After speaking of the struggle which, she says, she feels must occur with the Bad Spirit, she adds this:

"Do not think me very foolish in again requesting you not to go to St. Trinita di Monti. Although I am so much better, I cannot yet bring myself to believe all I heard and saw there, was a fevered dream. And without, as yet, being able to explain to myself the

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 5

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

reason, I dread your going there, without me. I trust I shall soon be able to tell you what has left so fearful an impression, but as yet I find it impossible. Heaven preserve me from passing another such day and night as I did then!"

I extract this, to shew you that I did not lay great stress on this creature, in my last, without strong reason. There can be no doubt that her position in reference to it is a very critical one; and that she is now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her.

Therefore I am more than ever anxious for your news from Geneva. I shall not fail, in writing to her tonight, to urge her again, to have no secret whatever from me, in connexion with this Fancy; and I shall try to shew her how unwise it is,

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 6

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

and how opposed to all my earnest wishes, that she should retain one, hidden in her breast. Do not lead in any way to the subject, lest she should think (which she would immediately) that I had given you any hint of this. But how unnecessary it is, that I should caution you who know her so well, and have studied and tended her with such delicate and loving care! My dear De la Rue, forgive me.

My agony is, lest any portion of the existing influence should be lost in prolonged separation—and lest that Devil in torturing her, should establish other secret horrors. In that case, how disheartening it would be to us (though I have no doubt of getting the better of them in time, even then) and what dreadful endurance to her!

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 7

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

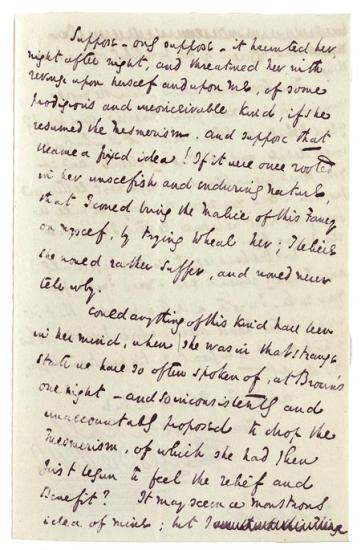

Suppose—only suppose—it haunted her, night after night, and threatened her with revenge upon herself and upon me, of some prodigious and inconceivable kind, if she resumed the Mesmerism. And suppose that became a fixed idea! If it were once rooted in her unselfish and enduring nature, that I could bring the Malice of this Fancy on myself, by trying to heal her; I believe she would rather suffer, and would never tell why.

Could anything of this kind have been in her mind, when she was in that strange state we have so often spoken of, at Brown's one night—and so inconsistently and unaccountably proposed to drop the Mesmerism, of which she had then just begun to feel the Relief and Benefit? It may seem a monstrous idea of mine; but

Letter 13 | 31 January 1845 | to Emile de la Rue, page 8

Autograph letter signed, Rome, 31 January 1845, to Emile de la Rue

Purchased in 1968

Shortly after his arrival in the United States in January 1842, Dickens told Dr. R. H. Collyer that, "with regard to my opinion on the subject of Mesmerism... I am a believer [but] I became so against all my preconceived opinions and impressions."

While in America, Dickens carried out his first mesmeric experiment on his wife, recalling that he "magnetized [hypnotized] her into hysterics, and then into the magnetic sleep." But his first significant efforts began in Genoa in December 1844, with his mesmeric treatment of Madame Augusta de la Rue. In this letter Dickens informed the husband of Madame de la Rue that she was "now in a state most favorable and advantageous to the best influence The Mesmerism could possibly exert upon her."

Mesmerism

In his life and art, Dickens worked energetically for healing. His fiction exposed many of the social ills of his day, and a significant portion of his later journalism is devoted to an impassioned campaign to improve sanitation and public health. Although he was a committed evolutionist and progressive in his attitude toward science and the improvements wrought by technological advances, he was also, by imagination and temperament, attracted to the fantastic and pseudoscientific. This was manifested in his interest in spontaneous combustion and phrenology as well as his fervent belief and active experiments in mesmerism (or "animal magnetism"), an early type of hypnotism.

Dickens was introduced to mesmerism through Dr. John Elliotson, his family physician and one of his "most intimate and valued friends." He became convinced of the therapeutic effects of mesmerism after witnessing Elliotson's demonstrations in 1838, and, although there is no record of Dickens undergoing the procedure, he learned to mesmerize others. Throughout the 1840s, he conducted mesmeric experiments on his wife and friends.

I am staggered by the possibility of such a thing.

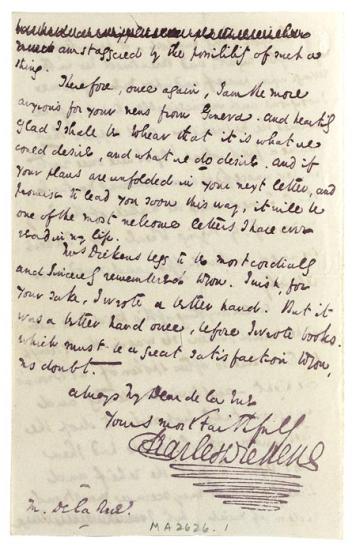

Therefore, once again, I am the more anxious for your news from Geneva. And heartily glad I shall be to hear that it is what we could desire, and what we do desire. And if your plans are unfolded in your next letter, and promise to lead you soon this way, it will be one of the most welcome letters I have ever read in my life.

Mrs. Dickens begs to be most cordially and Sincerely remembered to you. I wish, for your sake, I wrote a better hand. But it was a better hand once, before I wrote books. Which must be a great satisfaction to you, no doubt.

Always My Dear de la Rue | Yours most Faithfully

CHARLES DICKENS