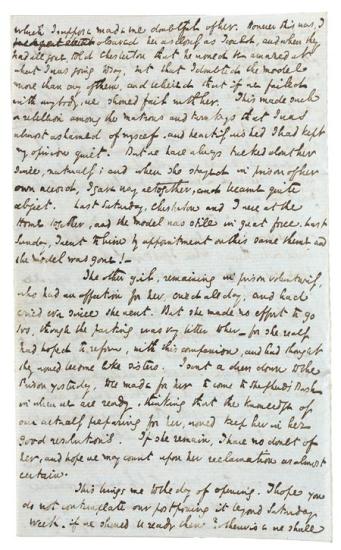

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 8

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

Which I suppose made me doubtful of her. However this was, I observed her as closely as I could, and when they had all gone, told Chesterton that he would be amazed at what I was going to say, but that I doubted the Model more than any of them, and believed that if we failed with anybody, we should fail with her. This made such a rebellion among the Matrons and turnkeys that I was almost ashamed of myself, and heartily wished I had kept my opinion quiet. But we have always talked about her since, naturally; and when she stayed in prison of her own accord, I gave way altogether, and became quite abject. Last Saturday, Chesterton and I were at the Home together, and the Model was still in great force. Last Sunday, I went to him by appointment on this same theme, and the Model was gone!—

The other girl, remaining in prison voluntarily, who had an affection for her, cried all day, and had cried ever since she went. But she made no effort to go too, though the parting was very bitter to her—for she really had hoped to reform, with this companion, and had thought they would become like sisters. I sent a dress down to the Prison yesterday, to be made for her to come to Shepherd's Bush in when we are ready, thinking that the knowledge of our actually preparing for her, would keep her in her good resolutions. If she remain, I have no doubt of her, and hope we may count upon her reclamation as almost certain.

This brings me to the day of opening. I hope you do not contemplate our postponing it beyond Saturday Week, if we should be ready then? otherwise we shall