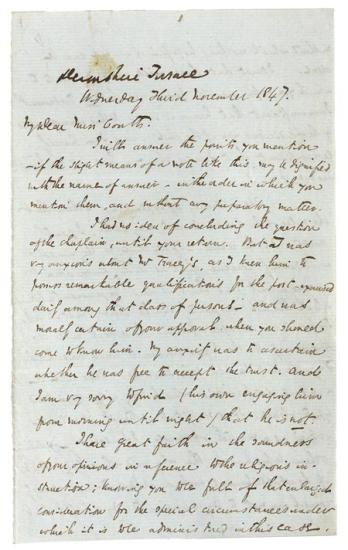

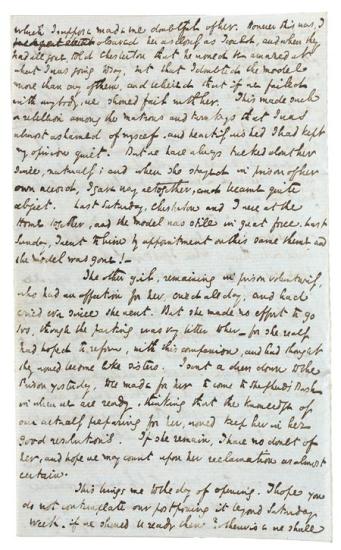

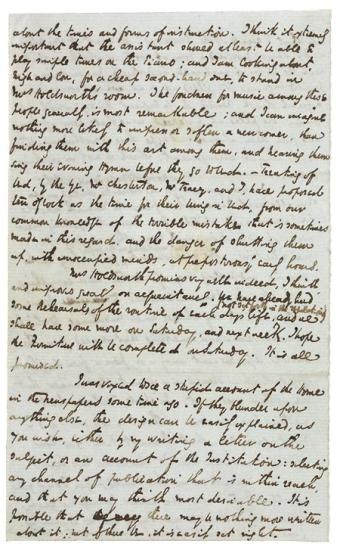

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 1

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

My Dear Miss Coutts.

I will answer the points you mention—if the slight means of a note like this may be dignified with the name of answer—in the order of which you mention them, and without any preparatory matter.

I had no idea of concluding the question of the chaplain, until your return. But I was very anxious, about Mr. Tracey's, as I knew him to possess remarkable qualifications for the post—exercised daily among that class of persons—and was morally certain of your approval when you should come to know him. My anxiety was to ascertain whether he was free to accept the trust. And I am very sorry to find (his own engaging him from morning until night) that he is not.

I have great faith in the soundness of your opinions in reference to the religious instruction; knowing you to be full of that enlarged consideration for the special circumstances under which it is to be administered in this case,

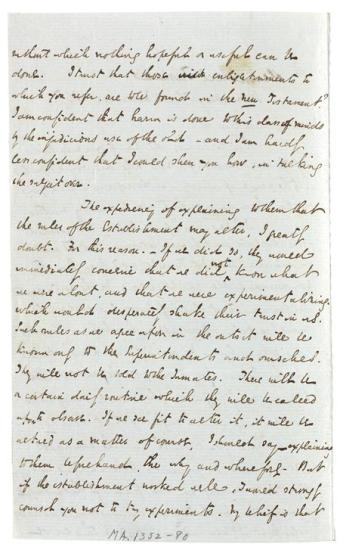

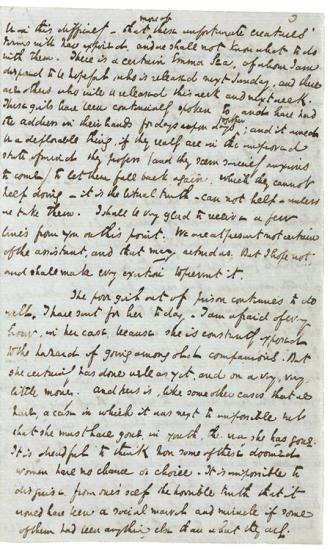

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 2

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

without which nothing hopeful or useful can be done. I trust that those enlightenments to which you refer, are to be found in the New Testament? I am confident that harm is done to this class of minds by the injudicious use of the old—and I am hardly less confident that I could shew you how, in talking the subject over.

The expediency of explaining to them that the rules of the Establishment may alter, I greatly doubt. For this reason.—If we did so, they would immediately conceive that we did not know what we were about, and that we were experimentalizing. Which would desperately shake their trust in us. Such rules as we agree upon in the outset will be known only to the Superintendents and ourselves. They will not be told to the Inmates. There will be a certain daily routine which they will be called upon to observe. If we see fit to alter it, it will be altered as a matter of course, I should say—explaining to them beforehand, the why and wherefore. But, if the establishment worked well, I would strongly counsel you not to try experiments. My belief is, that

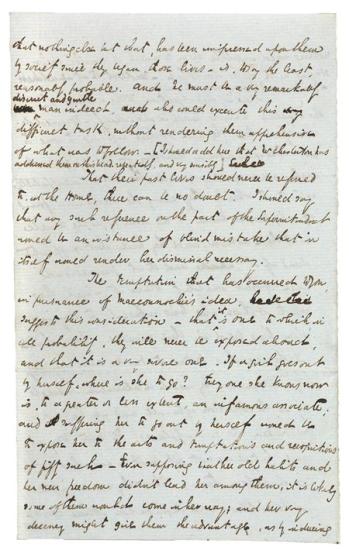

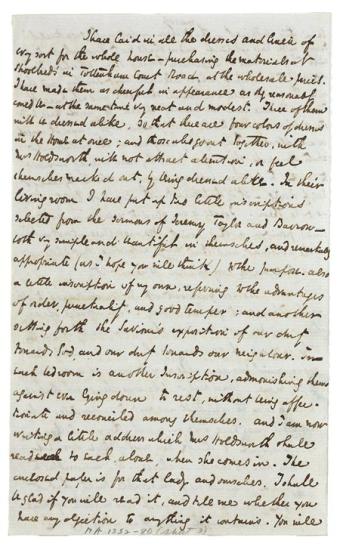

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 3

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

nothing would unsettle them so much, or render their staying with us so doubtful.—Recollect that we address a peculiar and strangely-made character.

There is this objection to the address of the chaplain to each person individually.—It would decidedly involve the risk of their refusing to come to us. The extraordinary monotony of the Refuges and Asylums now existing, and the almost insupportable extent to which they carry the words and forms of religion, is known to no order of people as well as to these women; and they have that exaggerated dread of it, and that preconceived sense of their inability to bear it, which the reports of those who have refused to stay in them, have bred in their minds. I am afraid if they were thus taken to task, and especially by a clergyman, they would be alarmed—would say "its the old story after all, and we have mistaken the sort of place. It's better to say at once that we are not fit for it"—and that so we should lose them. That they are sensible of the sinfulness and degradation of their lives—

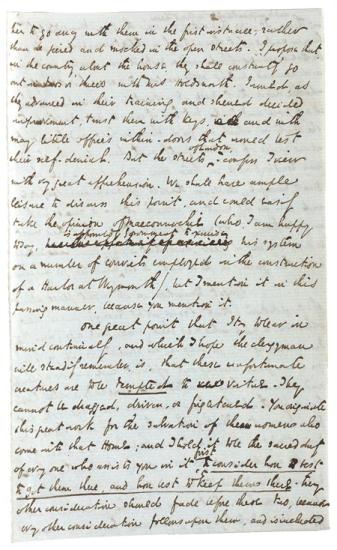

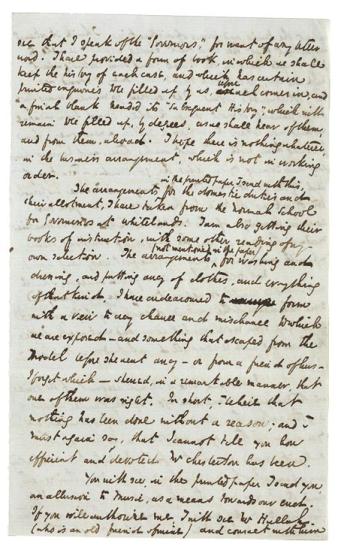

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 4

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

that nothing else but that, has been impressed upon them by society since they began those lives—is, to say the least, reasonably probable. And he must be a very remarkably discreet and gentle man indeed, who could execute this very difficult task, without rendering them apprehensive of what was to follow.—[I should add here that Mr. Chesterton has addressed them on this head, repeatedly, and very sensibly.]

That their past lives should never be referred to, at the Home, there can be no doubt. I should say that any such reference on the part of the Superintendent would be an instance of blind mistake that in itself would render her dismissal necessary.

The temptation that has occurred to you, in pursuance of Macconnochie's idea, suggests this consideration—that it is one to which in all probability, they will never be exposed abroad, and that it is a very severe one. If a girl goes out by herself, where is she to go? Every one she knows now is, to a greater or less extent, an infamous associate; and suffering her to go out by herself would be to expose her to the arts and temptations and recognitions of fifty such—Even supposing that her old habits and her new freedom didn't lead her among them, it is likely some of them would come in her way; and her very decency might give them the advantage, as by inducing

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 5

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

that nothing else but that, has been impressed upon them by society since they began those lives—is, to say the least, reasonably probable. And he must be a very remarkably discreet and gentle man indeed, who could execute this very difficult task, without rendering them apprehensive of what was to follow.—[I should add here that Mr. Chesterton has addressed them on this head, repeatedly, and very sensibly.]

That their past lives should never be referred to, at the Home, there can be no doubt. I should say that any such reference on the part of the Superintendent would be an instance of blind mistake that in itself would render her dismissal necessary.

The temptation that has occurred to you, in pursuance of Macconnochie's idea, suggests this consideration—that it is one to which in all probability, they will never be exposed abroad, and that it is a very severe one. If a girl goes out by herself, where is she to go? Every one she knows now is, to a greater or less extent, an infamous associate; and suffering her to go out by herself would be to expose her to the arts and temptations and recognitions of fifty such—Even supposing that her old habits and her new freedom didn't lead her among them, it is likely some of them would come in her way; and her very decency might give them the advantage, as by inducing

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 6

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

in them, and is impracticable without them. It is for this vital reason that a knowledge of human nature as it shews itself in these tarnished and battered images of God—and a patient consideration for it—and a determined putting of the question to one's self, not only whether this or that piece of instruction or correction be in itself good and true, but how it can be best adapted to the state in which we find these people, and the necessity we are under of dealing gently with them, lest they should run headlong back on their own destruction—are the great, merciful, Christian thoughts for such an enterprize, and form the only spirit in which it can be successfully undertaken. Do you not feel, with me, that this must be kept steadily in view, and that a chaplain imbued with this feeling in the outset, is the only Minister for this place?

I forgot to mention in its right place, about the temptation, that I saw, at Mr. Tracey's prison the other day, a girl who was there, some time ago (merely, if I remember right, for being in the streets, or, if for felony for some offence arising out of that life) whose appearance and behaviour had so interested some lady or other, living hard by, that when her term was over, she took her for a servant. That girl, although she had the reputation of being a drunkard, worked hard and honestly in this employment for seven or eight months, and had wine and spirits constantly in her keeping, which she never touched. But in an evil hour her Mistress gave her a holiday. She fell among her old companions

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 7

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

—her removal from whom had been the main cause of her reformation, poor creature—never went back again, fell into her old way of life, and is in prison now. I saw her with Mr. Chesterton, and talked to her, but thought it best to decline her: for besides the danger of her attachment to liquor (though I do not, like Mr. Chesterton: neither does Mr. Tracey attach overwhelming importance to that, in a young woman of that way of life, who drinks because she is utterly miserable—a middle aged woman who drinks, is another thing, and is always hopeless) she had a singularly bad head, and looked discouragingly secret and moody.

I must tell you of one of the two young women who were remaining in Prison voluntarily, until we could take them. When I first went there, about your home, she was produced to me by Mr. Chesterton, before I saw any of the others, as a model. She was the Matron's model, and the head female turnkey's model, and the peculiar pet and protegée of Mr. Rotch the Magistrate, who is a very good man, and takes infinite pains in the prisons—though I doubt his understanding of the company he finds there. She was much better educated than any of the others (some of whom are extremely ignorant), had a very intelligent face, and a remarkably good voice; but she impressed me as being something too grateful, and too voluble in her earnestness, and she seemed, in a vague, indescribable, uneasy way, to be doubtful of me.

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 8

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

Which I suppose made me doubtful of her. However this was, I observed her as closely as I could, and when they had all gone, told Chesterton that he would be amazed at what I was going to say, but that I doubted the Model more than any of them, and believed that if we failed with anybody, we should fail with her. This made such a rebellion among the Matrons and turnkeys that I was almost ashamed of myself, and heartily wished I had kept my opinion quiet. But we have always talked about her since, naturally; and when she stayed in prison of her own accord, I gave way altogether, and became quite abject. Last Saturday, Chesterton and I were at the Home together, and the Model was still in great force. Last Sunday, I went to him by appointment on this same theme, and the Model was gone!—

The other girl, remaining in prison voluntarily, who had an affection for her, cried all day, and had cried ever since she went. But she made no effort to go too, though the parting was very bitter to her—for she really had hoped to reform, with this companion, and had thought they would become like sisters. I sent a dress down to the Prison yesterday, to be made for her to come to Shepherd's Bush in when we are ready, thinking that the knowledge of our actually preparing for her, would keep her in her good resolutions. If she remain, I have no doubt of her, and hope we may count upon her reclamation as almost certain.

This brings me to the day of opening. I hope you do not contemplate our postponing it beyond Saturday Week, if we should be ready then? otherwise we shall

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 9

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

be in this difficulty—that more of these unfortunate creatures' terms will have expired, and we shall not know what to do with them. There is a certain Emma Lea, of whom I am disposed to be hopeful, who is released next Sunday, and there are others who will be released this week and next week. These girls have been continually spoken to, and have had the address in their hands for days upon days together; and it would be a deplorable thing, if they really are in the improved state of mind they profess (and they seem sincerely anxious to come) to let them fall back again. Which they cannot help doing—it is the literal truth—can not help—unless we take them. I shall be very glad to receive a few lines from you on this point. We are at present not certain of the assistant, and that may retard us. But I hope not, and shall make every exertion to prevent it

The poor girl out of prison continues to do well. I have sent for her to day. I am afraid of every hour, in her case, because she is constantly exposed to the hazard of going among old companions. But she certainly has done well as yet, and on a very, very little money. And hers is, like some other cases that we have, a case in which it was next to impossible but that she must have gone, in youth, the way she has gone. It is dreadful to think how some of these doomed women have no chance or choice. It is impossible to disguise from one's self the horrible truth that it would have been a social marvel and miracle if some of them had been anything else than what they are.

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 10

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house—purchasing the materials at Shoolbred's in Tottenham Court Road, at the wholesale prices. I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest. Three of them will be dressed alike, so that there are four colors of dresses in the Home at once; and those who go out together, with Mrs. Holdsworth, will not attract attention, or feel themselves marked out, by being dressed alike. In their living room I have put up two little inscriptions selected from the sermons of Jeremy Taylor and Barrow—both very simple and beautiful in themselves, and remarkably appropriate (as I hope you will think) to the purpose. Also a little inscription of my own, referring to the advantages of order, punctuality, and good temper; and another setting forth the Saviour's exposition of our duty towards God, and our duty towards our neighbour. In each bedroom is another Inscription, admonishing them against ever lying down to rest, without being affectionate and reconciled among themselves. And I am now writing a little address which Mrs. Holdsworth shall read to each, alone, when she comes in. The enclosed paper is for that lady and ourselves. I shall be glad if you will read it, and tell me whether you have any objection to anything it contains. You will

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 11

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

see that I speak of the "Governors", for want of any better word. I have provided a form of book, in which we shall keep the history of each case, and which has certain printed enquiries to be filled up by us, before each comes in, and a final blank headed its "Subsequent History", which will remain to be filled up, by degrees, as we shall hear of them, and from them, abroad. I hope there is nothing whatever, in the business arrangement, which is not in working order.

The arrangements in the printed paper I send with this, for the domestic duties and their allotment, I have taken from the Normal School for Governesses at Whitelands. I am also getting their books of instruction, with some other reading of my own selection. The arrangements (not mentioned in the paper) for washing and dressing, and putting away of clothes, and everything of that kind, I have endeavoured to form with a view to every chance and mischance to which we are exposed—and something that escaped from the Model before she went away—or from a friend of hers—I forget which—shewed, in a remarkable manner, that one of them was right. In short, I believe that nothing has been done without a reason; and I must again say, that I cannot tell you how efficient and devoted Mr. Chesterton has been.

You will see, in the printed paper I send you, an allusion to Music, as a means towards our end. If you will authorize me, I will see Mr. Hullah (who is an old friend of mine) and consult with him

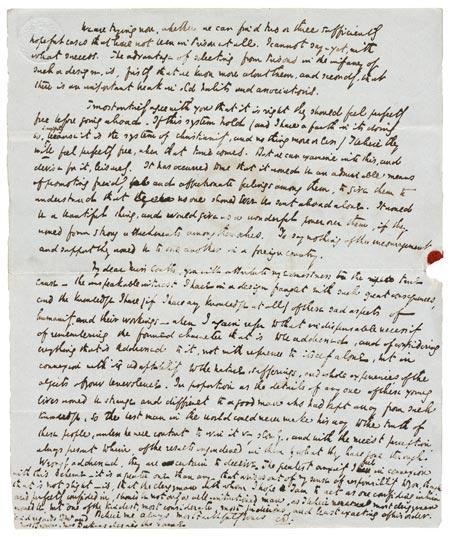

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 12

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

about the times and forms of instruction. I think it extremely important that the assistant should at least be able to play simple tunes on the Piano; and I am looking about, high and low, for a cheap second-hand one, to stand in Mrs. Holdsworth's room. The fondness for music among these people generally, is most remarkable; and I can imagine nothing more likely to impress or soften a new comer, than finding them with this art among them, and hearing them sing their Evening Hymn before they go to bed. Treating of bed, by the bye, Mr. Chesterton, Mr. Tracey, and I, have proposed ten o'Clock as the time for their being in bed, from our common knowledge of the terrible mistake that is sometimes made in this regard, and the danger of shutting them up, with unoccupied minds, at preposterously early hours.

Mrs. Holdsworth promises very well indeed, I think, and improves greatly on acquaintance. We have already had some Rehearsals of the routine of each day's life, (not set forth in the regulations) and we shall have some more on Saturday, and next week. I hope the Furniture will be completed on Saturday. It is all promised.

I was vexed to see a stupid account of the Home in the Newspapers some time ago. If they blunder upon anything else, the design can be easily explained, as you wish, either by my writing a letter on the subject, or an account of the Institution: selecting any channel of publication that is within reach, and that you may think most desirable. It is possible that there may be nothing more written about it: but if there be, it is easily set right.

Letter 3 | 3 November 1847 | to Angela Burdett-Coutts, page 13

Autograph letter signed, London, 3 November 1847, to Angela Burdett-Coutts

Purchased with the assistance of the Fellows, 1951

Dickens's letters to Burdett-Coutts are, by any standard, extremely long and detailed and reveal his extraordinarily competent administrative abilities as well as shrewd insight into the minds and motivations of the women who would enter Urania Cottage. He insisted "that their past lives should never be referred to." He also recognized "that these unfortunate creatures are to be tempted to virtue. They cannot be dragged, driven, or frightened." Dickens's meticulous attention to detail is apparent in this letter, in which he informs Burdett-Coutts that "I have laid in all the dresses and linen of every sort for the whole house... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be—at the same time very neat and modest."

Philanthropy

From 1840 Dickens guided the charitable work of philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814–1906), the wealthiest heiress in Victorian Britain. Dickens served as her official almoner and helped to assess the merits of the thousands of letters she received from those seeking financial assistance. He also advised on her plan for improved sanitation in the slums of Westminster and drew her attention and support to the Ragged School Union, which provided education to London's poorest children. A pragmatist, Dickens encouraged Burdett-Coutts to direct her philanthropy toward the causes of distress. In 1847 they founded a home, Urania Cottage, in Shepherd's Bush, as a shelter for homeless women—prostitutes or petty criminals who sought to rehabilitate themselves by learning practical skills and developing self-discipline. Many of the women were assisted to eventually emigrate to one of Britain's colonies to begin a new life. For more than ten years, Dickens administered Urania Cottage on behalf of Burdett-Coutts and played an extremely active role in its day-to-day management.

e are trying now, whether we can find two or three sufficiently hopeful cases that have not been in Prison at all. I cannot say—yet, with what success. The advantage of selecting from Prisons in the infancy of such a design, is, firstly that we know more about them, and secondly, that there is an important break in old habits and associations.

I most entirely agree with you that it is right they should feel perfectly free before going abroad. If this system hold (and I have a faith in its doing so, simply because it is the system of Christianity, and nothing more or less) I believe they will feel perfectly free, when that time comes. But we can examine into this, and devise for it, leisurely. It has occurred to me that it would be an admirable means of promoting friendly and affectionate feelings among them, to give them to understand that no one should Ever be sent abroad alone. It would be a beautiful thing, and would give us a wonderful power over them, if they would form strong attachments among themselves. To say nothing of the encouragement and support they would be to one another in a foreign country.

My Dear Miss Coutts, you will attribute my earnestness to the true cause—the unspeakable interest I have in a design fraught with such great consequences, and the knowledge I have (if I have any knowledge at all) of these sad aspects of humanity, and their workings—when I again refer to that indispensable necessity of remembering the formed character that is to be addressed, and of considering everything that is addressed to it, not with reference to itself alone, but in connexion with its adaptability to the nature, sufferings, and whole experiences of the objects of your benevolence. In proportion as the details of any one of these young lives would be strange and difficult to a good man who had kept away from such knowledge, so the best man in the world could never make his way to the truth of these people, unless he were content to win it very slowly, and with the nicest perception, always present to him, of the results engendered in them by what they have gone through. Wrongly addressed, they are certain to deceive. The greatest anxiety I feel, in connexion with this scheme—it is a greater one than any that arises out of my sense of responsibility to you, though that is not slight—is, that the clergyman with whom I hope I am to act as one confiding in him and perfectly confided in, should be not only a well-intentioned man, as I believe most clergymen would be, but one of the kindest, most considerate, most judicious, and least exacting of his order.

Believe me Always Most Faithfully Yours

CD.