Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy

I just have to accomplish what I set out to do, regardless of who or what is in my way.

—Belle da Costa Greene, New York Times, April 7, 1912

Bold, fearless, and uncompromising, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950) left an indelible mark on the Morgan Library as its first director. A pioneering figure, she broke barriers for women in the field of rare books and manuscripts. She was born Belle Marion Greener to an elite Black family in Washington, DC. A few years after moving to New York City in 1888, during the age of Jim Crow, she passed as white as Belle da Costa Greene, crossing the color line with her mother and siblings. She left no trace of her thoughts on racial passing and willed this aspect of her history into oblivion by destroying diaries and private papers. To friends and colleagues, however, she wrote thousands of pages of correspondence that capture her wit, humor, brilliance, and ambition. She was remembered as “the soul of the Morgan Library,” as a person whom one “would not have missed knowing for anything.”

This exhibition brings together the Morgan’s collection with objects from over twenty lenders to tell the intertwining narratives of Greene’s personal and professional lives against the backdrop of institutional and national histories. Her legacies are multiple and complex, yet her life resonates widely today and her memory endures.

This exhibition is organized by Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator and Department Head of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, and Erica Ciallela, Exhibition Project Curator.

Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy is made possible by lead support from Agnes Gund. Major support is provided by the Ford Foundation; Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin M. Rosen; Katharine J. Rayner; Denise Littlefield Sobel; the Lucy Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund; Desiree and Olivier Berggruen; Gregory Annenberg Weingarten, GRoW @ Annenberg; and by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom. Assistance is provided by the Franklin Jasper Walls Lecture Fund, the Friends of Princeton University Library, Elizabeth A.R. and Ralph S. Brown, Jr., and the Cowles Charitable Trust.

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925), Belle da Costa Greene, 1911. Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

Introducing Belle da Costa Greene

Listen to actor Andi Bohs read a quote by Belle Greene and co-curator Philip Palmer discuss Greene’s identity as a librarian.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print

Princeton University Art Museum, The Clarence H. White Collection, assembled and organized by Professor Clarence H. White Jr., and given in memory of Lewis F. White, Dr. Maynard P. White Sr., and Clarence H. White Jr., the sons of Clarence H. White Sr. and Jane Felix White; x1983-447

ANDI: My friends in England suggest that I be called “Keeper of Printed Books and Manuscripts” . . . but you know they have such long titles in London. I’m simply a librarian.

PHILIP: Through all of her shifts in circumstance and self-transformations, “librarian” is the word that most consistently defined Belle da Costa Greene’s identity. It was in her family’s DNA: her father, Richard T. Greener, after becoming the first Black student to graduate from Harvard College, became a librarian and professor at the University of South Carolina before the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877. When she applied to the Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies in 1896, she indicated on her application that she “would like to fit for Librarian.” Her first appearance as the head of household in a New York City directory, in 1912, lists her under “Green” as “Bella librarian.” For most of her career her signature and sign off in business letters read, “Belle da Costa Greene Librarian.” After Greene’s death, the book collector Anne Lyon Haight began writing an account of her good friend’s life, drawing on unpublished letters and interviews with people who knew her. Her working title? “The Training of a Librarian.”

But even a passing familiarity with Belle da Costa Greene’s life and career shows that her “simply a librarian” quote is a massive understatement. This was a librarian who spent fortunes at rare book auctions and commanded respect from prominent European curators. This was a librarian regularly featured in newspaper articles on the best-paid women in America, someone who collected fine art and Chinese sculpture. This was a librarian who drove a convertible and cavorted with aristocrats, who dined with avant-garde artists and parodied Gertrude Stein. This was a librarian, in other words, with verve and style uniquely her own.

Though Belle Greene ensured that much of her personal life and thoughts would remain unknowable—she burned her papers before her death—the archival legacy she left behind as a librarian and cultural heritage professional gives us a wealth of information about who she was and what she valued. Her love of art and the written word became the foundation of her professional identity, driving a strong commitment to collection access through research and exhibition programs. For Greene, a book was, as her bookplate suggests, “a friend who never changes.” She ensured that thousands of visitors to the Morgan would also have transformative experiences with books at the institution she often called “her” library.

Belle Greene’s mother, Genevieve

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela relate the story of Belle Greene’s mother, Genevieve, and discuss the uneven survival of documents related to women’s history

GENEVIEVE’S SOCIAL LIFE

Few archival traces of Belle Greene’s mother, Genevieve, have been preserved, as is unfortunately typical with the lives of historical African American women. This rare advertising flier lists “Mrs. R. T. Greener” second on a roster of “The Ladies of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church.” Other notable women here include the educator and Colored Women’s League member Ella Barrier, the teacher Sarah Ann Martin, and the teacher, activist, and poet Charlotte “Lottie” Forten Grimké, the minister Francis J. Grimké’s wife. Charlotte Grimké was well known for her writing and political activism, helping to form both the Colored Women’s League and the National Association of Colored Women.

Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church

“The Ladies of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church, Washington, D.C., Will Hold a Fair, Beginning December 22nd . . . ”

[Washington, DC, ca. 1880]

Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division; Printed Ephemera Collection; Portfolio 207, Folder 4a

ERICA: Tracing the life of Belle Greene’s mother has been a challenging task. Born Genevieve Ida Fleet into the prominent Fleet family of Georgetown, Washington, DC, Genevieve became a music teacher and educational administrator. She followed in the footsteps of several family members who taught or performed music, most prominently her father James H. Fleet. Unlike her more famous husband, Richard, whom she would marry in 1874, Genevieve’s life is captured in fleeting glimpses, preserved in newspaper articles, census documents, city directories, and ephemera, like this flier. No photographs of her as a student or Washington, DC resident survive today, and only a few of her letters are extant. This is fairly typical of women’s history, especially when tracing the lives of Black women, as their records were not as carefully preserved.

Genevieve came from a proud family that had been part of Georgetown’s free black community since the early nineteenth century. Many of the Fleet family members attended Mount Zion United Methodist Church, the oldest Black church in Georgetown, whose congregation formed in 1814. But Genevieve’s family attended the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in DC proper, presided over by influential abolitionist minister Francis J. Grimké, who implemented colorist policies in the church. This history reveals the complexity of the elite Black community in DC at this time, a story that is still being uncovered through research by Fleet descendants in DC and elsewhere today. We are grateful to Audri Cabness of Washington, DC—a Fleet family descendant—for sharing more about her family history with the exhibition’s curators.

Richard T. Greener

Listen to Jesse R. Erickson, the Morgan’s Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings, read a passage from Richard T. Greener’s handwritten autobiography (1870).

GREENER’S HARVARD DIPLOMA

GREENER’S HARVARD DIPLOMA

This vellum, handwritten diploma for “Richardum Theodorum Greener” conferred the bachelor of arts degree on Harvard’s first Black graduate. Perhaps the document’s most visible features are its water stains and faded signatures. These signs of distress speak to its incredible story. Long thought to have been lost during the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, when Greener lived on the West Coast, the diploma and other personal papers were discovered in 2009 by a contractor, Rufus McDonald, in the attic of an abandoned South Chicago house slated for demolition. McDonald consigned the document for sale in an auction, and it sold to Harvard University, which now preserves the diploma in its archives.

Richard T. Greener’s bachelor of arts diploma, Harvard College, June 28, 1870

Harvard University Archives; HUM 201 Box 1

Harvard University, Houghton Library

PHILIP: Belle Greene’s father, Richard T. Greener, led a fascinating life and pursued many professions after becoming Harvard’s first Black graduate. He was at times a professor, librarian, lawyer, writer, and diplomat. But he always strove to leave his greatest legacy as an activist seeking to uplift African-American communities in the United States. Greener was a gifted writer and public speaker and wanted his audience to remember his words. In this following manuscript autobiography excerpt, he wrote during his senior year at Harvard, Greener sought to set the record straight about his personal history while looking forward to a promising future.

JESSE: There are not many pleasant incidents in my college life to recall; the unpleasant ones I have no desire to hear of again.

My chief desire is to lead a purely literary life, in my own way.

I have a great fondness and some knowledge of Art. I am particularly interested in Metaphysics, general literature, and the Greek and Latin classics when divested of grammatical pedantry.

My plans in life are to get all the knowledge I can, make all the reputations I can, and “do good” and make a comfortable competence as the corollaries of the other two. I think I can do these best in the profession of Law.

I have been thus minute with my life, partly to remove many false impressions about me, such as that I escaped from slavery with innumerable difficulties; that I came direct from the cotton field to college; that I was a scout in the Union Army; the son of a Rebel-general etc., and partly because I have an impression that, perhaps, hereafter it will be pleasant for my classmates, and myself, to remember these things.

Richard Theodore Greener

Cambridge, May 19, 1870

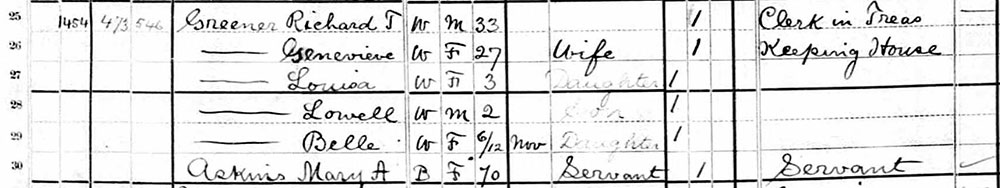

Belle Greene’s Family in the Census

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela talk about the history of race and the United States Census.

In the 1860 and 1870 US Censuses, the Fleets were designated “M” for “mulatto,” and the value of their personal property and real estate, the latter appreciating over the decade, are listed. The 1880 Census, taken after Genevieve had married Richard, finds the young Greener family living next door to Genevieve’s mother and siblings, with Belle, aged six months, appearing for the first time. Curiously, everyone in both households is listed as “W” for “white,” but this does not necessarily mean the family was passing at this time. Census records are highly mediated documents, and it is possible that the enumerator simply looked in the door, saw people with a light skin complexion, and assumed they were white.

Census Records Wall (reproductions). Detail from 1880 census, showing Belle Greene and her family listed.

ERICA: So many of us come to know our family histories through census records, a form of primary source material made accessible and familiar through resources like Ancestry.com and Family Search, or the popular television show Finding Your Roots. When we use the census to trace families impacted by enslavement and immigration, the records tell us as much about America’s relationship to race and ethnicity as they do about our personal histories. While Belle Greene’s mother’s family would be designated “M” for “Mulatto” in the 1860 and 1870 censuses, by 1930 Greene’s family could only select “White” or “Negro,” reflecting the advent of racial categories influenced by the one-drop rule. Until 1970, individuals counted in the census could not self-report their race but were assigned a category by census workers known as enumerators. When the young Greener family was counted for the 1880 census, the enumerator seems to have made a colorist assumption that the family’s light skin color meant they were “W” for “white.”

The racial identities of Americans were and still are impacted by these record-keeping practices. The rules will change once again for the next census in 2030, including for the first time an option to choose Middle-Eastern or North African and combining race and ethnicity into a single question.

The Earliest Known Belle Greene letter and photograph

Listen to co-curator Philip Palmer summarize Belle Greene’s educational career and actor Andi Bohs read Belle da Costa Greene’s earliest surviving letter.

Belle Greene left Northfield Seminary in 1898 without a degree, which was common for many of the school’s students at this time. In 1900 she attended the Summer School of Library Economy at Amherst College, about twenty-five miles south of Northfield. There she also learned the upright cursive handwriting she later used in her research notes and catalogue cards at the Morgan. This group photograph contains the earliest known image of Belle Greene, taken when she was twenty years old. She can be seen in the back row, against the ivy, with a wry smile and knowing expression. Like the other sitters, she signed the back of the photograph, where she recorded her name and hometown as “Belle Marion Greene, New York City.”

Amherst College Summer School, Fletcher Course in Library Economy, Class of 1900, 1900

Gelatin silver print

Amherst College Archives

PHILIP: Belle Greene wrote her earliest surviving letter just before starting boarding school at the Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies in 1896. Here she writes to Evelyn S. Hall of Northfield in late August 1896, promising to be at school and ready for class the following month.

ANDI: My dear Miss Hall: Yours of the 25th at hand. I fully expect to be present on the ninth of September. Shall send my baggage to East Hall as you direct.

Mother will have to leave home on the third or fourth of September for a short vacation as she is completely run down. She wishes to know if she may send my baggage on the third or fourth, direct to East Hall, E. Northfield, as she does not feel able to pay unnecessary expressage etc. to the country, & then to Northfield. She will be very glad indeed if it is possible to send my trunk direct to the Seminary. Will you kindly send us a line at the earliest opportunity?

Very sincerely,

B. Marion Greene

Thursday Evening August the twenty seventh

PHILIP: After Belle Greene left Northfield in 1898 she attended a summer library school course at Amherst College, where the earliest known photograph of her was taken. It is fitting that this photograph, only discovered in January 2023, is the earliest image of Greene and shows her in library school, training to pursue her life’s work.

The Drop Sinister

Listen to Jesse R. Erickson, the Morgan’s Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings, read W.E.B. DuBois’s 1915 review of Watrous’s The Drop Sinister.

In 1914, when this painting was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York, viewers did not know what to make of the work. W. E. B. Du Bois commented in The Crisis that some of the crowd was mystified, but “another part pretended that they understood it. ‘It is miscegenation,’ they croaked.” Du Bois wrote, “the people in this picture are all ‘colored,’” and contemplated how the child would be marked “Negro” on the census. Speaking of her life, he continued, “90,000,000 of her neighbors, good Christian, noble, civilized people are going to insult her, seek to ruin her and slam the door of opportunity in her face the moment they discover ‘The Drop Sinister.’”

Harry Willson Watrous (1857–1940)

The Drop Sinister—What Shall We Do with It?, 1913

Oil on canvas

Portland Museum of Art, gift of the artist; 1919.18

Image courtesy Luc Demers

PHILIP: Harry Willson Watrous’s enigmatic painting caused much conversation and debate. In his 1915 review for The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, activist and writer W.E.B. DuBois dramatized the painting’s contemporary reception.

JESSE: When this striking picture was exhibited at the New York Academy of Design a year or so ago it attracted great attention. There was a crowd continually around it. A part of the crowd did not understand it. “What does it mean” they asked. Another part pretended that they understood it. “It is miscegenation,” they croaked. Lest, therefore, the crowd surrounding this page of The Crisis should misunderstand this message and The Crisis should figure again in Congress as daring to picture white and black folk together, we hasten to explain.

The people in this picture are all “colored”; that is to say the ancestors of all of them two or three generations ago numbered among them full-blooded Negroes. These “colored” folk married and brought to the world a little golden-haired child; today they pause for a moment and sit aghast when they think of this child’s future.

What is she? A Negro? No, she is “white.” But is she white? The United States Census says she is a “Negro.”

What earthly difference does it make what she is, so long as she grows up a good, true capable woman? But her chances for doing this are small!

Why?

Because 90,000,000 of her neighbors, good, Christian, noble, civilized people, are going to insult her, seek to ruin her and slam the door of opportunity in her face the moment they discover “The Drop Sinister.”

Portraits of Belle Greene

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela interpret this portrait of Belle Greene and actor Andi Bohs read a passage from one of Greene’s letters.

AN EARLY PORTRAIT OF BELLE GREENE

This image made by the British-born American photographer Ernest Walter Histed is the earliest known solo portrait of Belle da Costa Greene. At this time Histed operated a studio on Fifth Avenue in New York City, though the circumstances under which he photographed Greene are unknown. Greene may have been referring to this image when she wrote in a 1910 of a “real” photograph of herself. While early images of Greene would share visual affinities with many of the light-skinned women depicted on the cover of The Crisis, as with the image of Georgia Douglas Johnson nearby, Greene’s portraiture as a white-passing woman would take a divergent path.

Ernest Walter Histed (1862–1947)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1910

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 2702

ERICA: People often find this photograph of Belle Greene to be more “authentic,” in that she is not wearing a hat, her hair is visible, and her skin is not brightened by tricks of lighting and pose. She is often described as more natural in this portrait. Greene may have been describing this image when she wrote the following lines to the art historian Bernard Berenson, her most famous lover and recipient of many of her photographs:

ANDI: I am sending you a “real” photograph such as you demand today – It may look rather sad for the simple reason that I was thinking of you all the time it was being taken (honestly) & that always makes me sad”

ERICA: Belle Greene became a newspaper celebrity in the early 1910s, appearing in articles about her, Morgan, and the Library. Though these pieces discussed her work as a librarian and curator, they typically began with patronizing comments on her skin tone, physical appearance, age, and beauty. Given how she was portrayed in the mass media, it is no surprise that Belle Greene rarely gave interviews and virtually disappeared from newspaper coverage after 1915.

The Octoroon Girl

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela talk about Archibald Motley Jr.’s painting The Octoroon Girl and read Georgia Douglas Johnson’s poem “The Octoroon” (1922).

THE OCTOROON GIRL

The portrait and genre-scene painter Archibald Motley Jr. made a series of three works that portray African American women based on their Creole racial classifications, including The Octoroon Girl, the most famous, as well as A Mulatress (1924) and The Quadroon (1927). The sitter in The Octoroon Girl, as in the sister paintings, remains nameless. She is only identified by her race, which is one-eighth Black. Born into a mixed-race family, Motley was raised in New Orleans and Chicago and experienced firsthand how these complex classifications determined social status and privilege.

Archibald Motley Jr. (1891–1981)

The Octoroon Girl, 1925

Oil on canvas

Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

© Estate of Archibald John Motley Jr. All reserved rights 2024 / Bridgeman Images

ERICA: The painter Archibald Motley Jr., like so many artists during the Harlem Renaissance, wanted to create images that highlighted the fullness of the Black experience while drawing attention to issues facing the community. He accomplished this aim beautifully through this elegant portrait that brings race, gender, and class into conversation, while reflecting his own background within the nuanced system of racial identity practiced in New Orleans. Three years before this painting was made, the poet Georgia Douglas Johnson wrote a poem titled “The Octoroon.” If Motley Jr.’s work appears to recognize and celebrate the sitter’s mixed-race identity, Johnson’s poem reminds us that, in the 1920s United States, the one-drop rule was starting to replace gradations of racial identity with the inflexible binary of “Black” and “White.”

“The Octoroon” (1922) by Georgia Douglas Johnson

One drop of midnight in the dawn of life’s pulsating stream

Marks her an alien from her kind, a shade amid its gleam;

Forevermore her step she bends insular, strange, apart—

And none can read the riddle of her wildly warring heart.

The stormy current of her blood beats like a mighty sea

Against the man-wrought iron bars of her captivity.

For refuge, succor, peace and rest, she seeks that humble fold

Whose every breath is kindliness, whose hearts are purest gold.

Princeton

Listen to co-curator Philip Palmer summarize Belle Greene’s career at Princeton and actor Andi Bohs read a letter Belle Greene wrote in 1909.

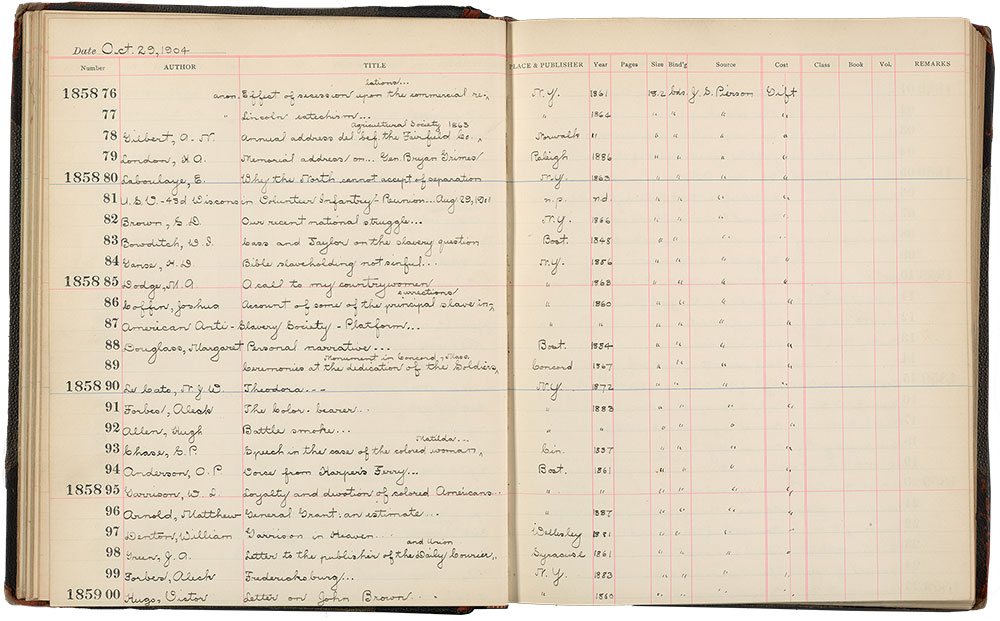

Handwritten accession ledgers document Greene’s work at Princeton. She used these books to track new acquisitions for the library, including the John Shaw Pierson Civil War collection, containing many titles about slavery, abolitionism, and race in America.

Accession Book 37, October 1904–March 1905

Princeton University Archives, Princeton University Library Records; AC123, Box 497

PHILIP: Belle Greene’s library career began at Princeton University, where she worked from 1901–1905. It was at Princeton that she worked with important mentors like librarian Ernest Cushing Richardson and benefactor Junius Spencer Morgan. It was undoubtedly difficult for Greene to pass as white at Princeton, given its racist policies, though we do not have any private writings about her experience there. In her letters to Bernard Berenson, Greene always described Princeton in positive terms, as in the following passage from a letter she wrote while visiting the University in 1909.

ANDI:

Princeton, N. J. Friday March 20 – Such a heavenly day as it is my dear – grey and misty and cold – the sort of day I love when one can snuggle up into one’s thoughts without being distracted by the glory of the Sun and the call of out-of-doors …

I came down here this afternoon as I hoped to spend a quiet weekend and find my dear friends have filled up every second of my time – Tonight we go to one of the students’ dances – tomorrow morning automobiling – in the afternoon to the first baseball game of the year – in the evening to a dinner at President Wilson’s etc etc. and my hopes & visions of a rest are thoroughly dissipated – I have such a weird time with the students. They are all so palpably young & I feel as if I had lived ages & ages before they were born & they can’t seem to realize how tiresomely old I am – It’s rather amusing for a few days – I must stop now and dress for dinner – only twenty minutes to my credit – I will write some more after I come back from the dance tonight

Belle Greene Builds the Collection

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela discuss Belle Greene’s acquisitions for the Library and actor Andi Bohs read a passage from a letter Greene wrote in 1909.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925)

Belle da Costa Greene, 1911

Platinum print

9 3/8 × 7 5/8 (23.9 × 19.2 cm)

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs, Box 12, Folder 37.

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

ERICA: Only a few years into her role at the Morgan Belle Greene was making major acquisitions for the collection and had earned Pierpont Morgan’s trust. One of her most famous quotes about her future ambitions for the collection comes from a letter she wrote her boss in 1909, announcing her purchase of the earliest surviving manuscript of Edgar Allan Poe’s famous poem, “The Raven.”

ANDI: I also bought the only existing manuscript of the Raven by Poe. The manuscript consists of a letter to Poe's friend Shea—enclosing the eleventh stanza of the famous poem and corrections for the 10th stanza. I think it one of the most important items in American literature and it is almost certain that the main draft of the poem was destroyed in the printing office of the Whig Review (as no trace of his has ever been found). I felt that this belonged with your other Poe manuscripts. It was offered by Hellman for $2500—I bought it at $1500. I have bought other books to fill gaps—one aim is to make the Library preeminent, especially for incunabula, manuscripts, bindings, and the classics. Our only rivals are the British Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale. I hope to be able to say some day that there is neither rival nor equal.

Bernard Berenson

Listen to co-curator Philip Palmer discuss Belle Greene’s letters to Bernard Berenson and hear actor Andi Bohs read a passage from one of them.

Theodore C. Marceau (1859–1922)

Series of portraits of Belle da Costa Greene, May 1911

Gelatin silver prints

Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs: Box 1 Friends (Large Format)

PHILIP: In the winter of 1909 Belle Greene met the love of her life, the art historian Bernard Berenson. They enjoyed a sweeping romance that would eventually cool into a friendly relationship between art world colleagues, corresponding for four decades in thousands of pages of personal writing. Greene destroyed the letters she received from Berenson, but Bernard saved all of Belle’s letters to him. They are now preserved just outside of Florence, Italy at I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies. The Morgan and I Tatti have created a new digital resource for the study of these letters, which truly highlight Belle Greene’s voice and personality. In the following early letter, she revels in the beauty of nature using a lyrical prose style.

ANDI:

Tuxedo – Easter Sunday

Sir – I embrace you! –

This is a most glorious Easter day – radiant with sunshine, and the world – like myself, is bubbling over with joy – This is one of the days which proves that I am a pagan pure and simple –

We had a most glorious horseback ride this afternoon – were out for over two hours – and if you have ever been here you know what a glorious country it is for riding –

Last night we had a real old fashioned barn-dance at the Higgins’ which was lots of fun – and tomorrow we are going off on a motor picnic. I know all this sounds very giddy and foolish to you oh! wise and learned Man – but the Spring has gotten into my blood and I am lost to all but reckless gayety. I feel as if I were the re-incarnation of the original bacchante and want nothing in the world but to laugh & sing and dance & be spoiled – You know I dearly love to be petted and spoiled – It is my greatest weakness – and I suppose I really ought to try – (at least) to overcome it – but I don’t –

[...]

What fun it would be to have you here – to go out into the woods – with all their promise of blooms with all their fresh colours washed by the dew before the dawn – to talk when we pleased, to walk when we pleased – sit down when we pleased – then “loaf on up the hill” – Nature has me in her bonds today and holds me with a grip of steel from which I have no desire to break away – I went out early this morning before anyone was down – and was all alone with the sunlight and a little stream of sparkling water that runs through the grounds, it was a curious feeling! a sense of something more. the water was more to one than water and the sun – than mere sun – the gleaming rays of the water in my hand held me for a moment, the touch of the water gave me something from itself. A moment, the gleam was gone, the water flowing away – but I had had them. I had received from them their beauty they had given me of their silent mystery – and I thought of you – dear – of the fleeting hours I had spent with you – and they too like the water & sunshine had flown away – but the beauty and mystery of them remain and in my thoughts are multiplied a thousandfold

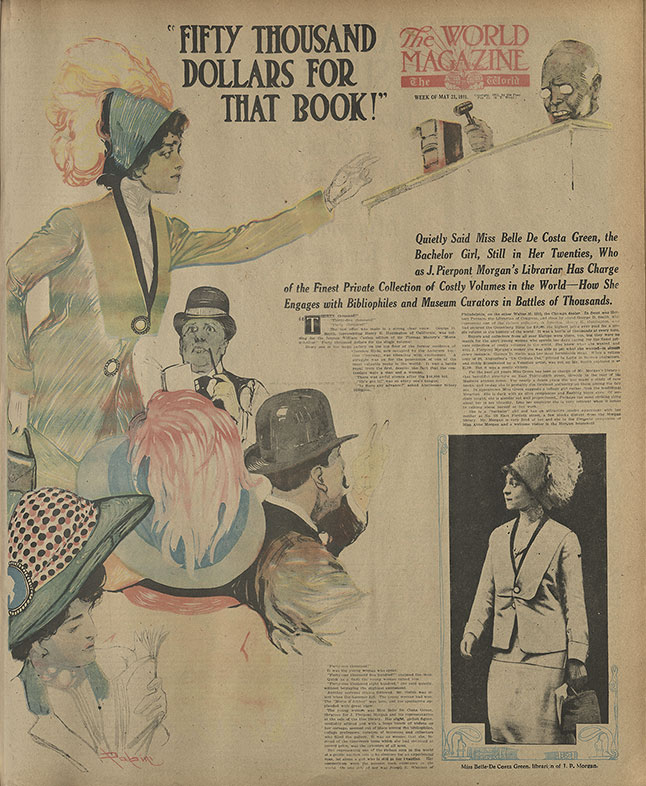

Greene in the Newspapers

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela talk about media coverage of Belle Greene’s acquisitions and hear actor Andi Bohs read a passage from one of her letters.

Alexander Popini (1878–1962)

Color-printed illustration imagining Belle da Costa Greene at the Robert Hoe sale

Reproduced from “Fifty Thousand Dollars for That Book,” The World Magazine, May 21, 1911

ERICA: In May 1911 Belle Greene made her most famous acquisition yet, winning at auction the only complete surviving copy of William Caxton’s printing of Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Her achievement made headlines and prompted this sensationally titled magazine article, “Fifty Thousand Dollars For That Book!” The morning after the article was published, Belle Greene was horrified when her mother showed her the piece.

ANDI: We arrived about brutal and I was “all in” so went immediately to bed and was awakened by mother bending over & holding up a horrible vision of myself in the Sunday World – full page & brightly coloured. Well I had a dozen different fits of anger and despair. You can’t do a thing with these damned newspapers – and although it said in the accompanying article that I was very quiet – & self-contained yet this picture was of half actress and half college girl – It really is too mean of them. If I behave in a dignified way when attending to my business why can’t they treat me in the same way in their newspaper or better still why can’t they leave me out? I was so cross that it has given me a violent headache & so I am spending the morning in bed.

Belle Greene’s Desk

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela discuss Belle Greene’s office furniture, as well as the actor Andi Bohs and co-curator Philip Palmer reading passages from correspondence between Greene and the London manufacturer who made the Library’s furniture.

Desk and swivel chair used by Belle da Costa Greene, 1906–7

The Morgan Library & Museum

ERICA: Belle Greene used this furniture in the Library’s North Office. It was from this desk that she oversaw the daily task of running the library and met with the many friends and professional colleagues she made throughout her career. The card catalogue cabinet, custom swivel chair, and desk were built by the London furniture manufacturer Bernard Cowtan & Sons. Correspondence with Cowtan survives in the Morgan’s Archives and documents the various details that Belle Greene wanted for her desk, as can be heard in the following exchange:

ANDI: Did I ask you to make a compartment on one of the drawers of my (personal) desk for holding a bunch of the catalogue cards? I enclose one for size. Also, could I have a sort of ‘box’ compartment for keeping money used in the ‘petty’ expenses of the library, and a place for stamps, etc. I hate to be such a nuisance but you spoiled me by saying I could have anything I liked.

PHILIP: It is no trouble at all to arrange the drawers in your own writing table to take a bunch of the catalogue cards, and one of the drawers to be devoted for the money and keys, with a place for the stamps, and we will space out the drawers accordingly; and I am not unmindful of the secret opening arrangement which we have spoken about.

Acquiring Medieval Manuscripts

Listen to co-curator Philip Palmer explain how Belle Greene acquired a priceless illuminated manuscript during the First World War and hear actor Andi Bohs reading Belle Greene’s letter to Jack Morgan announcing the purchase.

ONE OF HER FINEST ACQUISITIONS

In 1916, amid World War One, Belle Greene visited England and acquired what is now one of the most important illuminated manuscripts held in the United States. Commonly referred to as the “Crusader Bible,” it has had many owners, traveling from France to Italy, Poland, Iran, Egypt, and England. Though J. Pierpont Morgan had declined to purchase the manuscript in 1910 for £10,000, Greene was determined to secure it for Jack Morgan’s collection, even though he had not authorized wartime purchases. “If I had been able to stay here several weeks longer,” she wrote him, “I know I could have bought every important manuscript in private hands in England.”

Old Testament miniatures (“Crusader Bible”), in Latin, Persian, and Judeo-Persian

Paris, France, ca. 1244–54

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. P. Morgan Jr., 1916; MS M.638

PHILIP: Belle Greene daringly traveled to England during the First World War and purchased this manuscript, one of the finest sets of biblical miniatures in existence, without the express permission of her new boss, Pierpont Morgan’s son, Jack Morgan. The manuscript had been offered to Pierpont Morgan several years earlier, but he had turned down the offer. Knowing the immense research value and stunning beauty of the miniatures, Belle Greene returned to the manuscript’s owner in 1916 and closed the deal. The following is the letter she wrote to Jack Morgan to announce the acquisition.

ANDI:

My dear Mr. Morgan,

On my visit to Cheltenham this week I purchased from the present owner, Mr. Fitzroy Fenwick, his famous thirteenth-century French manuscript of the Bible Historiée, the finest example of French art of the period in private hands. It consists also of only 43 leaves—there are two others in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris (now in course of publication by the Comte de la Borde) and one at Cambridge—for this latter single sheet they paid, several years ago, £300. I agree to pay Fenwick £10,000 for his 43 leaves. The transaction makes me feel better about my ‘torpedoed’ letter of credit as Quaritch offered to try to obtain it for us for £15,000 plus his commission of 5% and Yates Thompson thought I would have to pay much more for it. Mr. Fenwick is coming to London to see me today, when we will arrange terms of payment and talk over 5 other manuscripts. I should like to have, or to have the promise of. If I had been able to stay here several weeks longer I know I could have bought every important manuscript in private hands in England. There was not time to get to the Duke of Northumberland’s collection (Duveen has just bought his Bellini) but I may be able to do something by correspondence.

Sincerely,

Belle Greene

An Interest in Persian and Indian Art

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela describe Belle Greene’s acquisitions of Persian and Indian miniatures and hear actor Andi Bohs read a letter from Belle Greene to British Museum curator Charles Hercules Read.

THE READ ALBUM

One of the treasures Greene and Berenson saw in Munich was an album of Persian and Mughal paintings and calligraphy from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. The collection belonged to Charles Hercules Read, keeper of British and medieval antiquities at the British Museum. In 1911 Greene wrote to Read, a friend and colleague, to ask if the album was for sale, explaining her rationale for the acquisition. She noted that, despite Morgan’s minimal interest in Persian and Mughal art, “in a collection of manuscripts and drawings such as he has, it is very necessary for him to have a representation of this most important school.” Greene’s interest in collecting Islamic art, among peer institutions, was ahead of its time.

Ibrāhīm Adham of Balkh served by angels

Faizabad, Oudh, India, ca. 1750–75

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911; MS M.458, fol. 32r

ERICA: In 1910 Belle Greene and Bernard Berenson visited an important exhibition of Islamic art in Munich, Germany. There she saw an album of Persian and Mughal miniatures on loan from the collection of British Museum curator Charles Hercules Read. Greene corresponded with Read extensively and in this letter asked him about the album she saw in Munich.

ANDI:

My dear Mr. Read:

You will remember that when you were in America you told me that you might find it necessary to sell your collection of Persian drawings, which I remembered having seen in the Exhibition in Munich last summer, and which at the time I considered among the finest things in the Exhibition. I do not know whether you still desire to part with these drawings; but, in case you do, I want to ask you if you will not give Mr. Morgan the first opportunity of purchasing them. Unfortunately, Mr. Morgan himself is not particularly interested in Persian art; but it seems to me that, in a collection of manuscripts and drawings such as he has, it is very necessary for him to have a representation of this most important school, and I doubt if he would ever be able to find finer specimens than those which you are so lucky as to own.

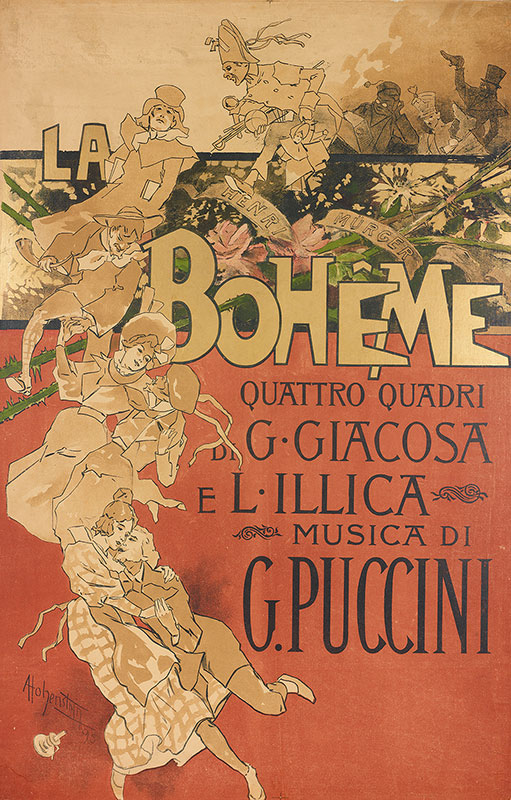

Love of Opera

Hear co-curator Philip Palmer discuss Belle Greene’s interests outside of work and actor Andi Bohs read a letter Belle Greene wrote describing a night out on the town in 1910.

Adolf Hohenstein (1854–1928)

La Bohême, quattro quadri di G. Giocosa e L. Illica. musica di G. Puccini

[Milan: Officine Grafiche Ricordi, 1895/96]

The Morgan Library & Museum, James Fuld Collection

PHILIP: Belle Greene made a name for herself working at the Morgan, but she led a fascinating life outside of the Library. She had a wide social circle in New York, often dining out with friends and attending the theatre or opera. She drove a Pierce Arrow convertible and enjoyed what was then called “motoring” in the countryside to escape the heat and crowds of Manhattan. She went to masked balls, hung out with modernist artists and writers, and formed her own art and antique jewelry collection.

One of her good friends was the English actor Ellen Terry, who was immortalized in her role as Lady Macbeth through John Singer Sargent’s famous painting. On Christmas Eve 1910 Terry and Greene spent the evening together out on the town, as recounted in this letter to Bernard Berenson.

ANDI: I have been seeing a good deal of Ellen Terry & Sara Bernhardt lately. Two women who fascinate me—Ellen Terry spent last night with me & it is a fact that we did not go to sleep until five o’clock this morning—Never have I seen any one so overflowing with vitality & the joy of living as she is. We went in the evening to see Humperdinck’s new opera the Königskinder which is very Wagnerian—very Tristan and in the dances a touch of Hansel & Gretel The Russian dancers gave a Ballet afterwards & I almost fainted with joy—Pavlowa [sic] does a thing called the Swan which is too wonderful and she and Mordkin did a Bacchante dance that simply took me off my feet. Then Frank Sturgis gave us a supper at the Metropolitan Club & we came home & had another supper (chiefly a smokers) in my tiny apartment & Ellen T. & I talked for two and a half solid hours & as I said it was five o’clock before either of us thought of supper or bed—My but that woman has lived and so has the divine Sara—Do you suppose I will ever have all those exciting experiences?

The Only Known Photograph of Genevieve Greene, Belle’s Mother

Listen to co-curators Philip Palmer and Erica Ciallela discuss the only surviving photograph of Belle Greene’s mother, Genevieve, and hear a passage from a letter written by Gertrude Tuxen, the woman who took the photograph ca. 1939.

THE ONLY PHOTOGRAPH OF GENEVIEVE

This previously unknown photograph of Genevieve was taken by a member of Belle Greene’s household staff, Gertrude Tuxen, while on a picnic in the Hudson Valley. The image shows Genevieve (at left) around ninety years old with another member of the staff and her family, as well as the household Pekingese dog, named “Hia Shua San.” The photograph conveys the visual foundation of racial passing, based in colorism, as Genevieve’s complexion appears quite light. The image helps explain how Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener could pass as Genevieve Van Vliet Greene, fit into the colorist social world of DC’s Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, be mistaken for white by Grace Dodge, and have children who could cross the color line.

Gertrude Tuxen

Genevieve Van Vliet Greene, Belle da Costa Greene’s mother, on an outing in the Hudson River Valley near Bear Mountain, ca. 1939

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 3297.1

PHILIP: Nearly twenty-five years ago a woman named Gertrude Tuxen wrote a letter to the Morgan Library. In it she recounted her days emigrating from Denmark and working for Belle da Costa Greene as a chambermaid in the late 1930s, a position she held for only a couple of years. Her letter is valuable not only for its description of Belle Greene’s apartment and family life, but also for the candid photographs she placed in the envelope. These show the household dog, a view from the apartment’s balcony, and, most importantly, the only known photograph of Belle’s mother Genevieve. The following is an excerpt from her letter.

ERICA: Belle da Costa Greene’s mother is to the left, my aunt Vica and uncle Harald Svantemann are next and Elise Olsen, housekeeper at Miss Greene’s Home, is the dark-haired lady. Another important member of this little group is the Pekinese at Mrs. Greene’s feet, Hia Shua San—called San—it was Elise Olsen’s great love, I remember she cooked calf liver for the dog, Miss Greene had acquired it on a trip to China. …

I was a domestic in Miss Greene’s household from ca. May 1939 until a short time after Denmark was invaded by Germany on April 9, 1940. Miss Greene lived on 66th Street between Madison and Park. She and her mother occupied the 7th floor which had its own elevator entrance. The home was a “museum” with many items from Miss Greene’s travels with JP Morgan, there were chairs you were not to sit on, and I was told that many things were museum bound eventually. The household consisted of Miss Belle da Costa Greene, her mother whom I addressed as Mrs. Greene. We referred to [her] as the “old lady,” her adopted son Bob—then a Harvard student—came now and again. Elise Olsen, a Norwegian, was cook and housekeeper, San, the Pekinese, I was chambermaid and dog walker, and had recently arrived from Denmark. …

Miss Greene must have been away, when it was decided to give Mrs. Greene an outing. As you will see we brought with us a very comfortable chair for the old lady, I don’t believe she had been out of the house in years. To begin with it was quite pleasurable for her to be on the trip, but it eventually became quite a strain for her, and I recall her saying “You are trying to kill me.” I am not sure Belle was ever told about this excursion, it was not repeated in my time there.

Modern Art

Listen to co-curator Philip Palmer talk about Belle Greene’s ambivalence toward modern art and hear the actor Andi Bohs read a passage from one of Greene’s letters.

MODERN DRAWINGS

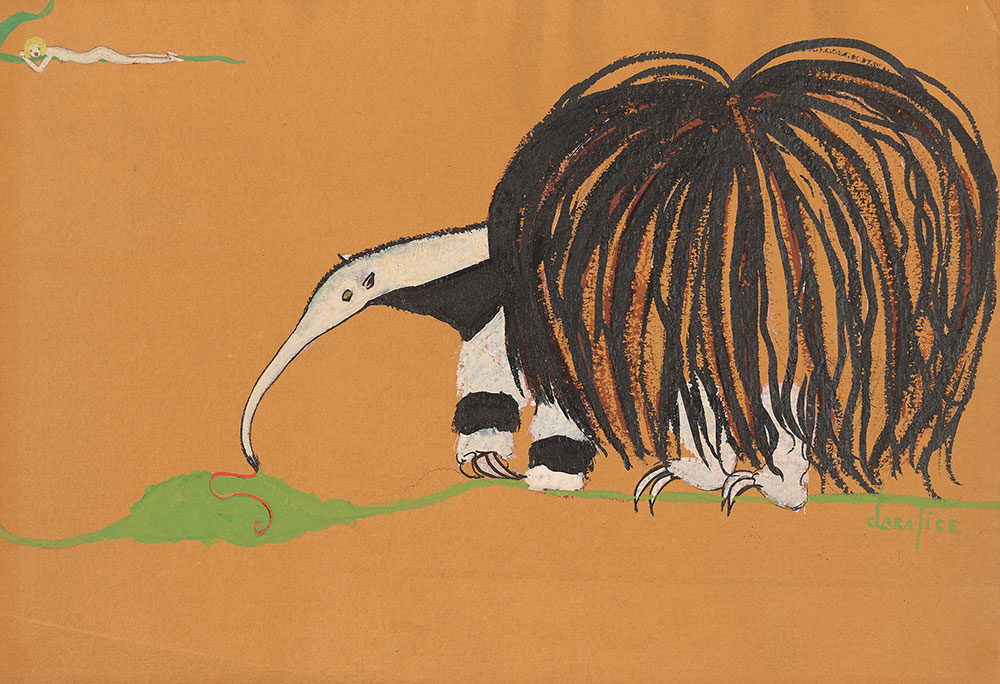

Belle Greene also collected drawings by modern artists, including her friend Everett Shinn (who drew “a dashing Carmen-like portrait” of her, now lost), Arthur B. Davies, Abraham Walkowitz, and Clara Tice. Many of these pieces are conventional nudes, though Walkowitz gave Greene two abstract drawings.

While no correspondence between Greene and Tice survives, they probably met one another and were in many ways kindred spirits. Known as “the Queen of Greenwich Village,” the bold and outspoken Tice first exhibited her watercolor nudes in 1910, and her work was subject to an infamous raid by the anti-obscenity zealot Anthony Comstock in 1915. It was probably at her 1922 exhibition Animals and Nudes that Greene purchased this drawing.

Clara Tice (1888–1973)

Anteater, twentieth century

Opaque watercolor over graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gifts of the Estate of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950; 1950.35

Used with permission of the Clara Tice family.

PHILIP: Given Belle Greene’s association with the largely historical collections of the Morgan Library, it may come as a surprise to know that she moved in some of New York’s avant-garde circles. She owned drawings by Henri Matisse, Abraham Walkowitz, and Clara Tice, known as the “Queen of Greenwich Village.” Marius de Zayas caricatured Greene and she contributed an article to Alfred Stiegltiz’s periodical Camera Work. As signaled in that piece, she always had an ambivalent attitude toward modern art, finding it at once attractive and repulsive. A similar perspective is on display in the following passage from one of her letters, in which she describes encountering “a wild bunch” of modernist artists at a restaurant.

ANDI: I rode aimlessly down Lipton Avenue until I saw the Holland House and suddenly decided to go in there and have a bit all by myself – At the door I was greeted by a wild bunch of men that we call the “Secessionists” here – Steiglitz & Marin & de Zayas & Havemeyer & Bliss Carman and they insisted that I have luncheon with them. They are so sincere in their outlandish “futurism” and other ism’s that one cannot help liking them – even though not one in the crowd had a clean collar or a shaven face – They took me over to their little attic room, later to see the latest outpourings of Picabia, Picasso and this little Marin …

Belle Greene’s Politics

Listen to co-curators Philip Palmer and Erica Ciallela discuss Belle Greene’s political activism during the Presidential election of 1916 and hear a passage from a pamphlet on women’s political activity.

WOMEN IN NATIONAL POLITICS

Greene served as treasurer for the Women’s Roosevelt League, a group organized in 1916 to support Charles Evans Hughes’s presidential campaign. In the September leading up to the election, she traveled with the league to Washington, DC, for a conference on the role of women in politics. The women photographed alongside Greene came from similar social circles. Maude Wetmore cofounded a camp for young women and was a friend of Anne Morgan—J. Pierpont Morgan’s youngest daughter and a prominent philanthropist in her own right. Katherine Davis was an advocate for women in New York reformatories. Alice Carpenter was an active leader in the suffrage movement and managed the women’s department at a Wall Street brokerage firm.

Members of Women’s Roosevelt League for Hughes. Left to right Mrs. Jos G. Deune, Sec’y., Miss Alice Carpenter, Pres., Miss Belle Greene, Treas., ca. 1916. Library of Congress, Photographs and Prints Division

PHILIP: Belle Greene became involved in the 1916 U.S. Presidential election to support the Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes, who sought to extend the vote for women. She was tapped into the larger National Hughes Alliance, which supported the candidate, but also volunteered her time to the Women’s Roosevelt League for Hughes. This photograph was taken during a Roosevelt League gathering. A pamphlet about womens’ efforts to elect Hughes, shown nearby, begins with a foreword addressing the need to report their activities and celebrate politically active women.

ERICA: The Women’s Committee of the Hughes Alliance is publishing a report of its work in the recent campaign because it believes that its many thousands of contributors, workers and members should know what was done and how it was done. We believe that the work of this Committee has a message for women in future American political campaigns.

There is a second reason for this report. The deliberate misrepresentation concerning the women’s work has grown to such proportions that we believe the public is entitled to the facts regarding the women’s campaign in general and the women’s campaign train in particular. The women’s movement in national politics has come to stay. This report covers something of its manner of coming and may have a message for those interested in the manner of its staying.

Director of the Pierpont Morgan Library

Listen to actor Andi Bohs read a passage from a Belle Greene letter describing her aspirations for the Morgan Library, as well as co-curators Erica Ciallela and Philip Palmer summarizing the many accomplishments Greene achieved as director.

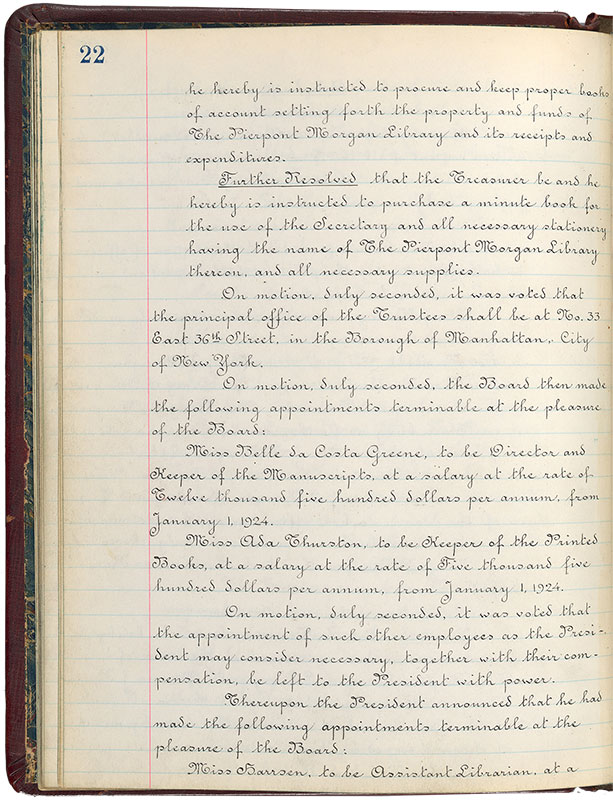

A NEW ERA

With the transformation of Morgan’s private collection into a public educational institution, it was now Greene’s responsibility to serve a community outside of the Morgan family. The institution was established as a “public library, for reference only . . . for the use and benefit . . . of all persons whomsoever, subject only to suitable rules and regulations.”

Greene’s appointment is recorded in this beautifully handwritten book with the board’s meeting minutes, which also indicate that Ada Thurston, Greene’s first hire, would stay on as the “Keeper of Printed Books.” Jack Morgan served as the inaugural board president.

Minutes of the Pierpont Morgan Library Board of Trustees, 1924

The Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 3294, Box 1425, v. 1

ANDI: If I can make a big institution out of it – it will be all that I or anyone else can expect – I shall start in just as soon as this inventory business is over – to see what I can do to make it a dernier ressort for scholars in certain fields, to make our material available to them and to make them welcome here.

ERICA: In 1924 Belle Greene’s wish came to fruition and the private library of Pierpont and Jack Morgan became the Pierpont Morgan Library. Greene was appointed its first director. In this section, you will see many facets of Greene’s work as librarian and director: her commitment to education and special collections teaching, her blockbuster exhibitions, her support of publication projects and research, her interest in preservation techniques, her remarkable acquisitions, and her dedication to collection access.

When the Morgan began mounting major exhibitions and opening its doors to researchers in the 1920s, newspaper accounts remarked on the important dual mission of the institution to serve both scholars and the public, as in the following anecdote:

PHILIP: It is difficult to say which will be the greater usefulness traceable to Mr. Morgan’s gift, the work done by specialists in the original Morgan library, or the pleasure and instruction derived by much larger audiences from popular exhibitions of the Morgan Library’s resources, of which we trust the present is only the first.

Accessing the Collection

Listen to co-curator Philip Palmer discuss the history of researchers accessing the Morgan’s rare collections.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

Reading Room, ca. 1928–60

Reproduction of a photographic print

The Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 1913.4

PHILIP: Though scholars had been able to access the Morgan’s collection for many years, the Library was always closed if Pierpont was out of town, and in its earliest days access was highly limited. The following anecdote from 1908 offers colorful detail about how prospective researchers accessed the Library:

One had to ring an outside bell to have the door opened by a guard, and then only about four inches. A business card would be passed in and the door would be closed again and locked. After a short interval, the guard would reappear and state if Miss Greene would see the caller. After a few visits, I was admitted at once.

All of this changed when the Library went public in 1924. When the first reading room opened in 1928, it followed the access policies laid out by the Board of Trustees, which stipulated that the institution is a “public library, for reference only . . . for the use and benefit . . . of all persons whomsoever, subject only to suitable rules and regulations.” The Board clearly took its role seriously in establishing a policy to provide access to the collection but also to protect and preserve it. An early goal was “to encourage quality of scholarship rather than ‘numbers’ of students.” This meant that researchers were required to submit letters of recommendation and schedule special appointments with staff to consult “reserved” books and manuscripts, such as Shakespeare’s First Folio. The earliest set of rules did not allow undergraduates to consult rare materials, though by 1933 that rule had been relaxed.

Black Librarianship

Listen to co-curator Erica Ciallela discuss Belle Greene’s place in the history of Black librarianship.

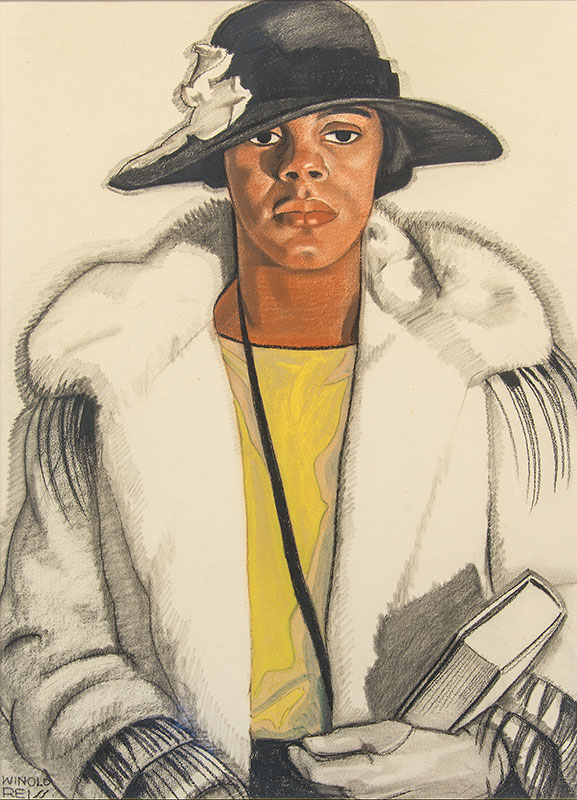

A HARLEM LIBRARIAN

Winold Reiss made numerous portraits of Harlem residents in the 1920s, including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, Alain Locke, and other well-known cultural figures. But he also painted anonymous sitters and created composite portraits such as The Librarian. The image was reproduced as part of the series “Four Portraits of Negro Women” in the landmark March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic, titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro”—an important publication of the Harlem, or “New Negro,” Renaissance. The portraits precede the educator Elise Johnson McDougald’s article “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation.”

Winold Reiss (1886–1953)

The Librarian, 1925

Pastel and tempera on Whatman board

Fisk University Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee

Photography by Jerry Atnip

ERICA: Telling the story of Belle Greene’s work as a librarian demands that we turn our attention to the lives and careers of other Black librarians working in the same era. This section therefore honors Catherine Latimer, who worked at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Regina Andrews, also of NYPL; Vivian Harsh of the Chicago Public Library; and Dorothy Porter Wesley of Howard University. These women were pioneers in their work and fought hard to bring literacy and information access to their communities. They were also inspiring speakers and writers.

Vivian Harsh once said, “If we as Negroes knew the full truth about what we, as a race, have endured and overcome just to stay alive with dignity, our respect and hunger for education would triple overnight.”

Despite making up only a small fraction of the profession, Black librarians are deeply proud of their work and outspoken in their advocacy for their communities. When Dr. Carla Hayden was appointed the Fourteenth Librarian of Congress in 2016, she brought a heightened visibility to Black librarians on a national stage. As she once said, “Now we are fighters for freedom, and we cause trouble! We are not sitting quietly anymore.”

Belle da Costa Greene was a Black librarian, even if she did not identify as such. Her work as a librarian did not impact Black communities in the same way as did the practices of her contemporaries, such as Catherine Latimer at NYPL. This is not to diminish Greene’s accomplishments in any way, but rather to uplift the work of other Black librarians at the time who have not been as prominently discussed as Greene.

A Legacy Remembered

Listen to co-curators Philip Palmer and Erica Ciallela discuss Belle Greene’s legacy at the Morgan and beyond.

When Belle da Costa Greene retired in 1948, letters came in from around the world congratulating her on the contributions she had made to the Morgan and scholarship at large. She had not only built an inspiring collection but also shaped the careers of women she mentored, including Morgan librarian Meta Harrsen and Walters Art Gallery curator Dorothy Miner. Several years after her retirement, staff members would even continue to say fondly that they were working on projects for “Miss Greene.”

But her legacy has extended far past the lifetimes of those who knew her. Her story has galvanized the work of scholars, biographers, writers, and artists. Awards and fellowships have been named in her honor, including the Medieval Academy of America’s Belle da Costa Greene Award, Belle da Costa Greene Scholarships to support booksellers and librarians attending antiquarian book seminars in Colorado and York, and the Morgan’s own Belle da Costa Greene Curatorial Fellowships, established in 2019 and given to “promising scholars from communities historically underrepresented in the curatorial and special collections fields.” Despite the gaps she left in the narrative, both intentional and not, Greene’s singular devotion to the world of librarianship remains one of her most enduring legacies.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925) Belle da Costa Greene, 1911 Platinum print 9 13/16 × 7 5/16 (24.9 × 18.5 cm) Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies; Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers, Personal Photographs, Box 12, Folder 37

The Bernard and Mary Berenson Papers. Biblioteca Berenson I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

PHILIP: To honor her retirement and celebrate an exceptional career, the Morgan mounted an exhibition of Belle Greene’s best acquisitions in 1949. A New York Times review remarked not only on the exhibition’s treasures, but the remarkable legacy of the woman who brought them together in one building. Here is a passage from the beginning of the review.

There are many people who may have contemplated the treasures of the Morgan Library without ever meeting personally its erstwhile director, Belle da Costa Greene. But no one there could have been unaware of her taste, her intelligence, her dynamism. For it was Miss Greene who transformed a rich man’s casually built collection into one which ranks with the greatest in the world.

ERICA: Belle Greene’s life impacted so many people during her lifetime, and her legacy continues to inspire new generations of readers, museum visitors, and library professionals today. When her friends and colleagues published a tribute volume of essays to honor her memory in 1954, Greene’s protégé Dorothy Miner wrote a foreword that imagined what a biography of her former boss might look like. As she wrote,

A biography of Belle Greene would be a fascinating and colorful account with a fabulous array of personalities, settings, and incidents. It would move against a backdrop of princely palaces and international playgrounds, austere libraries and remote cloisters, of academic meetings and the world of society. … It would be full of triumphs and fairy-tale successes, gaiety and humor, irony, sorrow, bravado, and courage. … Above all, it would be a tale crowded with people—people of every kind and station—some known to all the world by reason of power or accomplishment, some the most obscure of students.

It was this very democratizing impulse, to serve the scholar and student alike, that made Greene such a special librarian and the Morgan such a singular place.