Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature

Creator of memorable animal characters like Peter Rabbit, Squirrel Nutkin, and Mr. Jeremy Fisher, the children’s book author and illustrator Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) rooted her fiction in the natural world. Born in London, Potter spent her childhood summers in Scotland and in northwest England’s Lake District. These early experiences of the countryside nourished her love of nature, and, as with her famous menagerie of pets, inspired her picture letters and published tales.

Potter’s studies of plants and fungi established an abiding interest in the life sciences, a passion that she would bring to rural life at Hill Top Farm in the Lake District. There she enjoyed a second act as a sheep breeder and land conservationist, ultimately bequeathing four thousand acres, including farmland, to the National Trust for England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Potter’s legacy persists not only in her books but in the environment itself: her efforts helped preserve the natural spaces that fostered her scientific pursuits and fired her imagination.

Organized by the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), London, the exhibition brings together artworks, books, manuscripts, and artifacts from several institutions in the United Kingdom, including the V&A, the National Trust, and the Armitt Museum and Library. Paired with the Morgan’s exceptional collection of Potter’s picture letters, these objects trace how her innovative blend of scientific observation and imaginative storytelling shaped some of the world’s most popular children’s books.

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943), Mrs Rabbit pouring out the tea for Peter while her children look on, 1902–1907. Linder Bequest. Museum no. BP.468. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, / courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

This exhibition at the Morgan is organized by Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator and Department Head of Literary and Historical Manuscripts.

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature was created by the V&A – Touring the World

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature is made possible by major support from the Drue Heinz Charitable Trust, the Drue Heinz Exhibitions and Programs Fund, Susan Jaffe Tane, and an anonymous donor, with generous support from Katharine J. Rayner, the Christian Humann Foundation, the Caroline Morgan Macomber Fund, and Rudy L. Ruggles, Jr.

Family

Rupert Potter (1832–1914)

Bertram Potter holding one of his paintings at Lingholm, Keswick, October 1901

Albumen print

V&A: Linder Bequest BP.1534

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Hi, my name is Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor curator and department head of Literary and Historical Manuscripts at the Morgan Library and Museum. I'm the organizing curator for Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature.

Beatrix Potter was born into a family with roots in the North of England, a strong track record in business, and an abiding fascination with the arts. Her paternal grandfather Edmund Potter became rich running a successful Calico printing business in Derbyshire, yet was influenced by the radical labor perspectives of his wife, Jessy, and her family, the Cromptons of Lancashire. Potter made sure his fortune benefited the lives and education of his workers, for whom he built a library and reading room, as well as a school for their children (though it must be said that he was staunchly opposed to trade unions). He would later serve in Parliament and move to London, where he would become involved with cultural institutions such as the National Gallery of Art and the Kensington School of Art.

His second son Rupert, Beatrix’s father, did not go into the family business but instead studied law and became a London solicitor. He appreciated the arts and practiced drawing, but perhaps his greatest creative passion was photography. Many of the family portraits shown in this gallery were taken by Rupert, including the image of Beatrix’s brother Bertram holding one of his paintings.

Beatrix’s mother, Helen Leech Potter, also came from a North Country family, the Leeches of Manchester. Her father John Leech married into a wealthy cotton manufacturing family, and he and his wife Jane Ashton Leech lived in a stately mansion known as Gorse Hall. Their daughter Helen would later produce a watercolor of their home, shown nearby. Like the Potters, the Leeches also eventually moved to London, and it was there that Rupert and Helen met and married. They both owned works of art that graced the walls of their Kensington home, a townhouse located at 2 Bolton Gardens. Works by William Henry Hunt and Randolph Caldecott not only registered the aesthetic sensibilities of the family but gave Beatrix an early model for her artistic ambitions.

Secret Diary

Andrew Finlay Mackenzie (1846–1940)

Studio portrait of Beatrix Potter, ca. 1892

Albumen print on gilt-edged, lithographed card

V&A: AAD/2006/4/472, Given by Joan Duke

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Rather than securing her private thoughts in a locked journal, Beatrix devised an elaborate code to encrypt her life-writing as a teenager. What follows is an entry from the spring of 1884, taken from the page on display in front of you:

Minehead, Thursday, April 24th, 1884

We had a splendid drive round by Dunster, Timberscombe and Cutcombe to Dankery Beacon. We did not go right up to the Beacon, but over the brow of the hill the view was splendid in spite of the haze. Looking South over the upper Exe Valley it was not very interesting, but northward to Wales over the long narrow strip of Channel it was very fine. I was particularly struck by the horizon appearing so high. I must have often before seen the sea from higher mountains round, which makes the elevation seem less.

The scenery was very beautiful going down into the Horner Valley, but I think the descriptions of it exaggerated the size. To any one who has seen Scotland and the Lakes both woods and river appear on a very small scale. Going through the oak wood and past Cloutsham Hall, which is anything but round, we rested at the farm, and came home through Luccombe. Unfortunately we saw no deer, though a herd of thirty-one had crossed into the valley the night before, and were living in the Horner Woods.

Truly we are kept going; now when the dynamiters let us alone old mother earth gives us an explosion. I wish I had been in London to feel it slightly. One does not often get a chance of feeling an earthquake fortunately, in nature that is to say, for domestic ones are only too frequent.

Near to Home

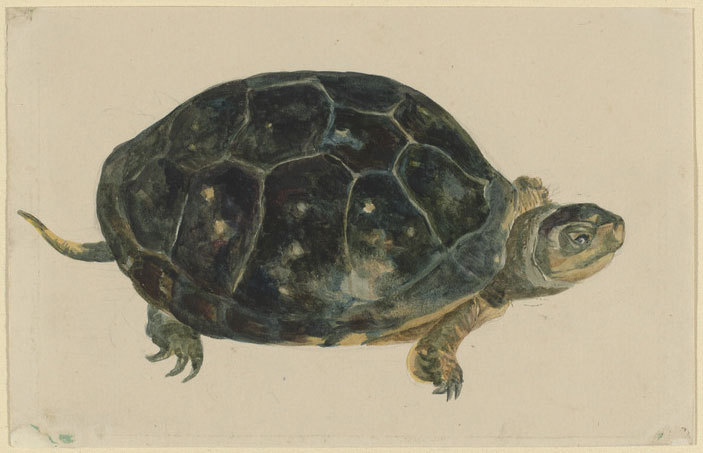

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Terrapin, probably drawn at London Zoo, ca. 1905

Watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite

V&A: LC 19/\A/4, Given by the Linder Collection

Image courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

The Potters’ Kensington home, southwest of Hyde Park in London, was situated near two of the city’s great centers of culture and knowledge: the Natural History Museum and what was then called the South Kensington Museum. (It was renamed the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1899 after Queen Victoria and her late husband, Prince Albert.) These places gave Beatrix a creative outlet as a young person and nourished her love of art and nature. At the South Kensington Museum she would sometimes copy design elements in the collection, such as the pattern shown nearby copied from a frieze. The museum’s famous costume collection would later inspire her picture book The Tailor of Gloucester. She also frequented the nearby London Zoo, located in Regent’s Park, where she probably drew this watercolor of a terrapin. Later in life she would return to the zoo near her home to sketch owls from nature, aiming to perfect drawings for another picture book, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin.

Beatrix and Bertram’s World

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Beatrix’s pet lizard Judy, from Ilfracombe, Devon, February 1884

Watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite

V&A: Linder Bequest BP.405

Image courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

The third-floor nursery of the Potters’ home was a schoolroom dedicated to furthering Beatrix and Bertram’s education. Without recourse to the woodlands and open fields enjoyed by children in the countryside, Beatrix and Bertram made this space their special domain—a place to keep their growing menagerie of pets, collect specimens from the natural world, and conduct studies and experiments.

In this room you will see many of Beatrix’s drawings and watercolors taken from nature, ranging from botanicals and insect studies to sketches of mice and her beloved rabbits, Peter Piper and Benjamin Bouncer, the inspirations for Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny. The insect studies are sophisticated from a biological perspective, and were in some cases reproduced as lithographs for the possible use in natural history instruction at a nearby London college.

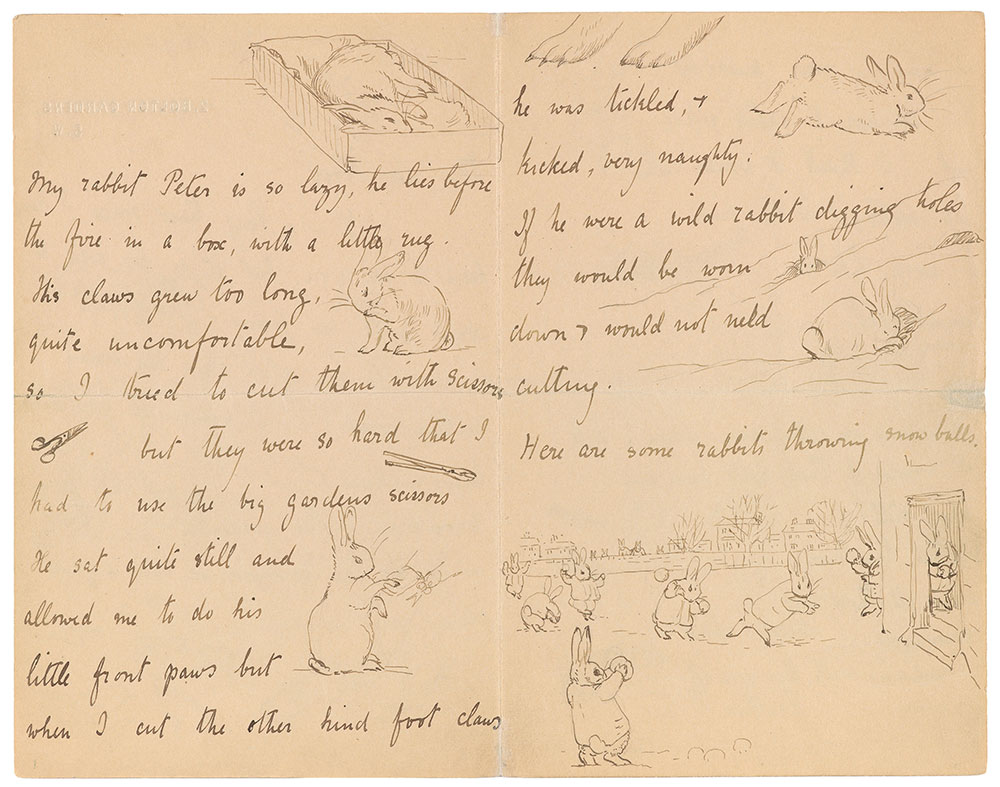

My rabbit Peter is so lazy

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Illustrated letter to Noel Moore, February 4, 1895

Ink

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Colonel David McC. McKell, 1959, MA 2009.2

The Morgan owns twelve of Beatrix Potter’s celebrated picture letters written to children. In one of the most delightful letters from this collection, she entertains her correspondent with a description of her pet rabbit, Peter Piper:

My dear Noel,

It is a long time since I have been to see you, but it is too cold to drive with my pony. I shall be very glad when the warm weather comes. I wonder if you have been making a snow-man in the garden? Or feeding the sparrows, we have a great many every morning.

My rabbit, Peter, is so lazy, he lies before the fire in a box, with a little rug. His claws grew too long, quite uncomfortable, so I tried to cut them with scissors but they were so hard that I had to use the big garden scissors. He sat quite still and allowed me to do his little front paws but when I cut the other hind foot claws he was tickled, & kicked, very naughty. If he were a wild rabbit digging holes they would be worn down & would not need cutting.

Here are some rabbits throwing snow balls.

I wonder if your pussycat has learned to catch mice yet. I think it would rather lap milk, it is too fine to work like a common cat.

These mice are getting away down a hole.

I wonder if those dolls have any hair still & whether they have eaten all those nice sausages.

I remain with love yrs aff.

Beatrix Potter

A Passion for Fungi

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Amanita crocea (yellow grisette) and Amanita muscaria (scarlet fly cap), Ullock, Cumbria,

September 2–3, 1897

Watercolor, white heightening, and graphite

V&A: Linder Bequest BP.244

Image courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

One of the most interesting aspects of Beatrix Potter’s life is her interest in mycology, the study of fungi. Historically, fungi have been overlooked in favor of plants and the study of botany. This was true in Beatrix Potter’s time and is often still the case today. But Beatrix was drawn to these humble organisms, with their underground mycelium shooting forth from the soil in the fruiting bodies of mushrooms. Some of her most vibrant natural historical drawings depict fungi in a scientifically accurate manner, showing cross-sections and spores.

Her fascination with fungi is revealed in her correspondence with the naturalist Charles MacIntosh. In one of these letters she describes a mushroom she grew in the dark:

“It is a pale straw colour, grown entirely in the dark, and there are nearly 100 ‘fingers’, the longest measure 1 1/4 inch. Miss Potter wonders whether it grows out of doors at this season or whether it is brought out by the heat of the room? It was about this size when first observed but being moved into a hot cupboard near the kitchen chimney, it puffed out in a very odd shape.”

In the Country

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Leaves and flowers of the orchid cactus, 1886

Watercolor and graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Charles Ryskamp in honor of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Morgan Library and the 50th anniversary of the Association of Fellows, 2000.34.

One of Beatrix’s favorite places to visit on holiday was the home of her paternal grandparents, Edmund and Jessy, at Camfield Place, located in the county of Hertfordshire north of London. Jessy, whose maiden name was Crompton, came from a family that espoused radical perspectives on questions of labor and class. Bold, independent, and outspoken, Jessy was well liked by Beatrix, who enjoyed her family stories.

One of the eleven objects on display from the Morgan’s collection is this drawing of an orchid cactus kept by Jessy Potter at Camfield. Beatrix memorialized her grandmother’s house plants with this drawing, but also kept some pieces of furniture from Camfield, such as a heart-shaped chair.

The Potter family’s vacations, a shorter trip in the spring followed by a longer sojourn in late summer, took them south to the coasts of Devon, Cornwall, and Dorset; as well as north to Scotland and the Lake District. In the rest of the gallery you will see many of the drawings and picture letters Beatrix made while traveling outside of London.

Lake District

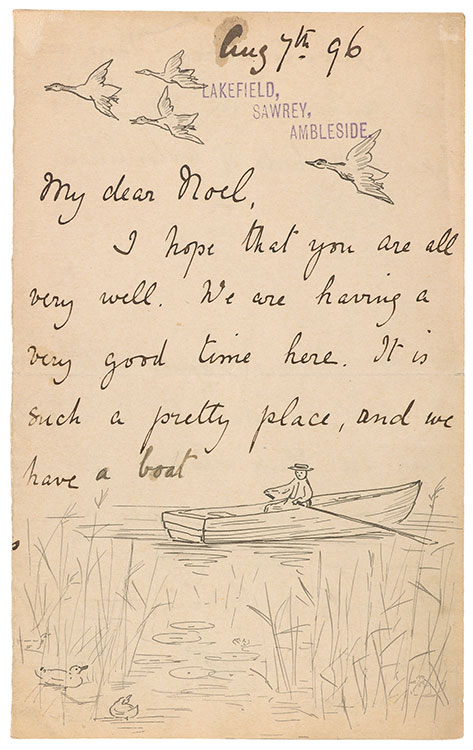

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Illustrated letter to Noel Moore, August 7, 1896

Ink

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Colonel David McC. McKell, 1959, MA 2009.8.

From a young age Beatrix visited the Lake District on vacation with her family. In this picture letter, written at the age of 30, Potter depicts herself rowing a boat within the natural beauty of the Lakes:

My dear Noël,

I hope that you are all very well. We are having a very good time here. It is such a pretty place, and we have a boat on Esthwaite Lake. There are tall rushes at the edge of the lake and beds of water lilies.

I sometimes sit quite still in the boat & watch the water hens. They are black with red bills and make a noise just like kissing, when they are hiding in the reeds. They walk on the lily leaves, nodding their heads and peeping underneath for water snails. There are wild ducks too, but they are not so tame. One evening I went in the boat when it was nearly dark and saw a flock of lapwings asleep, standing on one leg in the water. What a funny way to go to bed! Perhaps they are afraid of foxes, the hens are.

There are some cocks & hens on the hill, who sleep right at the top of a hawthorn bush, the branches are quite covered with chickens. Those at the farm go up a stone wall into a loft. The farmer has a beautiful fat pig. He is a funny old man, he feeds the calves every morning, he rattles the spoon on the tin pail, to tell them breakfast is ready, but they won't always come, then there is a noise like a German band.

I remain yrs. aff.

Beatrix Potter

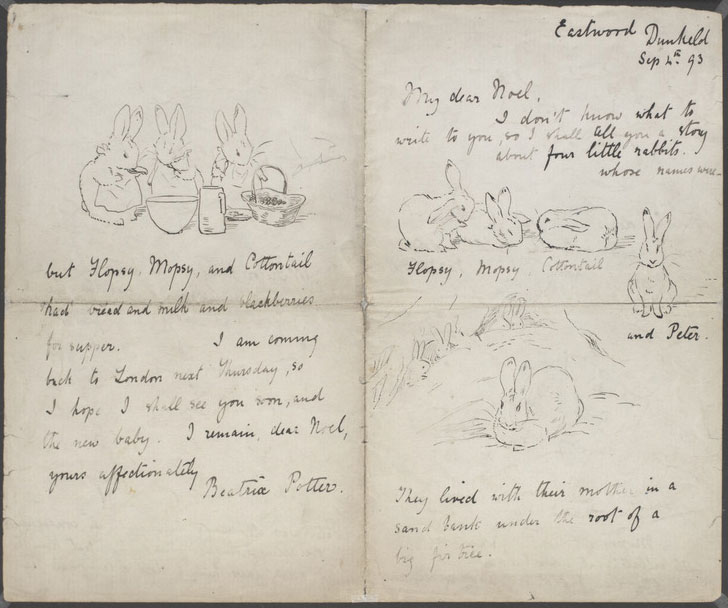

The Original Peter Rabbit Letter

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Illustrated letter to Noel Moore, September 4, 1893

Ink

Pearson PLC

Image courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit originated as one of Beatrix Potter’s memorable picture letters. With some encouragement from a friend, she transformed this private letter into one of the world’s best-known children’s books. One page of the letter can be seen framed on the wall, and the rest can be read on the nearby touchscreen or heard in the following reading:

My dear Noel,

I don’t know what to write to you, so I shall tell you a story about four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter.

They lived with their mother in a sand bank under the root of a big fir tree.

“Now my dears,” said old Mrs. Bunny, “you may go into the field or down the lane, but don’t go into Mr. McGregor’s garden.”

Flopsy, Mopsy & Cottontail, who were good little rabbits, went down the lane to gather blackberries, but Peter, who was very naughty, ran straight away to Mr. McGregor’s garden and squeezed underneath the gate.

First he ate some lettuce, and some broad beans, then some radishes, and then, feeling rather sick, he went to look for some parsley; but round the end of a cucumber frame whom should he meet but Mr McGregor!

Mr McGregor was planting out young cabbages but he jumped up & ran after Peter waving a rake & calling out ‘Stop thief’!

Peter was most dreadfully frightened & rushed all over the garden, for he had forgotten the way back to the gate.

He lost one of his shoes among the cabbages and the other shoe amongst the potatoes. After losing them he ran on four legs & went faster, so that I think he would have got away altogether, if he had not unfortunately run into a gooseberry net and got caught fast by the large buttons on his jacket. It was a blue jacket with brass buttons, quite new.

Mr McGregor came up with a basket which he intended to pop on the top of Peter, but Peter wriggled out just in time, leaving his jacket behind, and this time he found the gate, slipped underneath and ran home safely.

Mr McGregor hung up the little jacket & shoes for a scarecrow, to frighten the black birds.

Peter was ill during the evening, in consequence of overeating himself. His mother sent him to bed and gave him a dose of camomile [sic] tea, but Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail had bread and milk and blackberries for supper.

I am coming back to London next Thursday, so I hope I shall see you soon, and the new baby. I remain, dear Noel, yours affectionately

Beatrix Potter

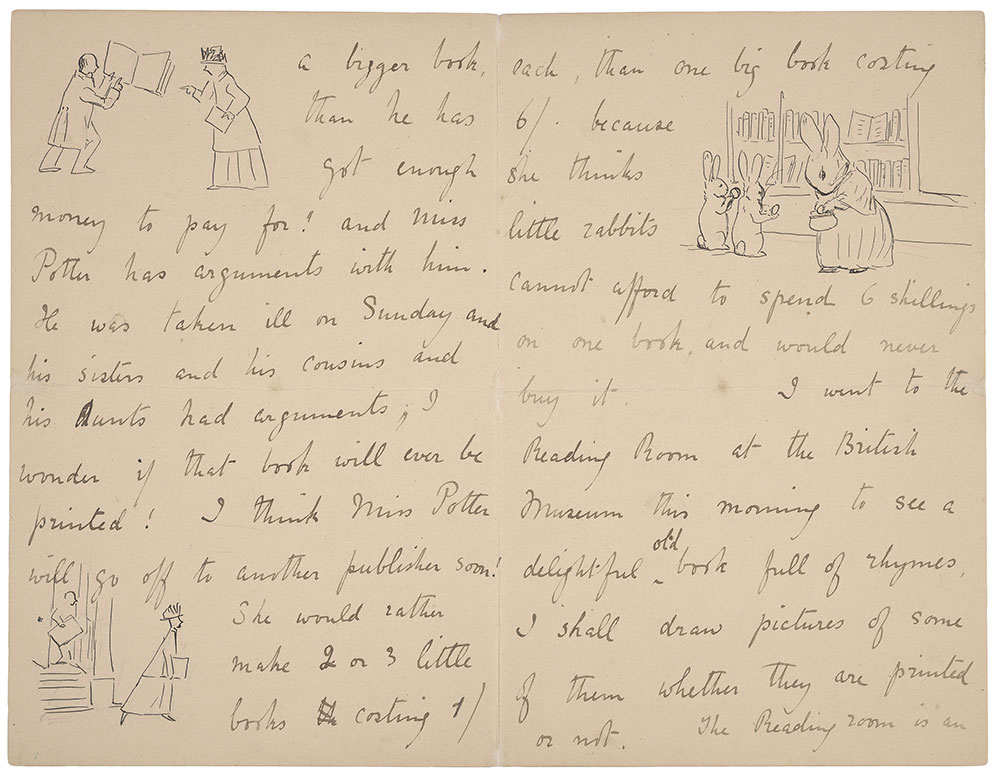

Little Books

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Illustrated letter to Marjorie Moore, March 13, 1900

Ink

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Colonel David McC. McKell, 1959, MA 2009.12

In this picture letter written to Noel Moore’s sister, Marjorie, Beatrix details her disagreements with publishers about the format of her books. She was uncompromising in her vision for small, affordable volumes, now a hallmark characteristic of her literary work for children:

My dear Marjory,

You will begin to be afraid I have run away with the letters altogether! I will keep them a little longer because I want to make a list of them, but I don't think they will be made into a book this time because the publisher wants poetry. The publisher is a gentleman who prints books, and he wants a bigger book than he has got enough money to pay for! and Miss Potter has arguments with him. He was taken ill on Sunday and his sisters and his cousins and his aunts had arguments; I wonder if that book will ever be printed! I think Miss Potter will go off to another publisher soon! She would rather make 2 or 3 little books costing 1/ each, than one big book costing 6/ because she thinks little rabbits cannot afford to spend 6 shillings on one book, and would never buy it.

I went to the Reading Room at the British Museum this morning to see a delightful old book full of rhymes. I shall draw pictures of some of them whether they are printed or not. The Reading Room is an enormous big room, quite round, with galleries round the sides, the walls covered with books, and hundreds of chairs and desks on the floor. There were not many people, but some of them were very funny to look at! And there are some people who live there always but Miss Potter didn't see them, although they are said to be the largest people of their sort in London! Next time Miss Potter goes to the British Museum she will take some Keating's powder. It is very odd that there should be fleas in books!

The Tale of Two Bad Mice

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Finished artwork for The Tale of Two Bad Mice, February–June 1904

Watercolor and pen and ink

The National Trust: Hill Top and Beatrix Potter Collection

© National Trust / Robert Thrift

Philip: You will now hear a reading from The Tale of Two Bad Mice, read by the actor Richard Armitage:

The Dolls’ House stood at the other side of the fireplace. Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca went cautiously across the hearth rug. They pushed the front door. It was not fast. Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca went upstairs and peeped into the dining room. Then they squeaked with joy. Such a lovely dinner was laid out upon the table. There were tin spoons and lead knives and forks, and two dolly chairs, all so convenient! Tom Thumb set to work at once to carve the ham. It was a beautiful, shiny yellow streaked with red. The knife crumpled up and hurt him. He put his finger in his mouth. “It's not boiled enough. It's hard. You have a try Hunca Munca.” Hunca Munca stood up in her chair and chopped at the ham with another lead knife. "It's as hard as the hams at the cheesemongers'', said Hunca Munca.

The ham broke off the plate with a jerk and rolled under the table. "Let it alone", said Tom Thumb, "Give me some fish, Hunca Munca." Hunca Munca tried every tin spoon in turn. The fish was glued to the dish. Then Tom Thumb lost his temper. He put the ham in the middle of the floor and hit it with the tongs and with the shovel. Bang, bang, smash, smash. The ham flew all into pieces, but underneath the shiny paint, it was made of nothing but plaster. Then there was no end to the rage and disappointment of Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca. They broke up the pudding, the lobsters, the pears, and the oranges.

Hill Top

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Drawing of Hill Top, Near Sawrey (before renovations), ca. 1905

Ink and graphite

V&A: LC 15/A/1, Given by the Linder Collection

In 1905 Beatrix Potter purchased Hill Top Farm in the small Lake District village of Near Sawrey. Once she moved to the Lake District full-time in 1913, she lived with her husband William Heelis in nearby Castle Cottage, reserving Hill Top as a place to write, draw, and preserve various family heirlooms and trinkets. The bed warming pan, shown nearby, was once owned by Beatrix’s favorite grandmother, Jessy.

This space has been designed to capture the feel and character of Hill Top farmhouse. The wallpaper, one of the earliest designed by the artist William Morris, can still be seen at Hill Top today. The window seat is a conspicuous feature of the seventeenth-century farmhouse and appears in The Tale of Tom Kitten, one of Beatrix’s “Hill Top Tales,” all four of which are available for reading nearby. Objects related to two of these books, The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck and The Tale of Samuel Whiskers, show how farm life crept into Beatrix’s fiction.

The Tale of Jeremy Fisher

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Finished artwork for The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, ca. 1906

Watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite

The National Trust: Hill Top and Beatrix Potter Collection

© National Trust / Robert Thrift

Philip: Here is a reading from The Tale of Jeremy Fisher by the actor David Harewood:

Mr. Jeremy shoved the boat out again a little way, and dropped in the bait. There was a bite almost directly, and the float gave a tremendous bobbit. "A minnow! A minnow; I have him by the nose!" cried Mr. Jeremy Fisher, jerking up his rod. But what a horrible surprise; instead of a smooth, fat minnow, Mr. Jeremy landed Little Jack Sharp, the stickleback, covered with spines. The stickleback floundered about the boat, prickling and snapping until he was quite out of breath. Then he jumped back into the water and a shoal of other little fishes put their heads out and laughed at Mr. Jeremy Fisher. And while Mr. Jeremy sat disconsolately on the edge of his boat, sucking his sore fingers and peering down into the water, a much worse thing happened; a really frightful thing it would've been if Mr. Jeremy had not been wearing a mackintosh. A great big, enormous trout came up- Kerplop!- with a splash, and it seized Mr. Jeremy with a snap. "Oh!, Oh!" And then it turned and dived down to the bottom of the pond. But the trout was so displeased with the taste of the mackintosh that in less than half a minute it spat him out again. And the only thing it swallowed was Mr. Jeremy's galoshes.

Appley Dapply’s Nursery Rhymes

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Old Mister Prickly Pin (later renamed Mr. Pricklepin), pages from the draft Book of Rhymes manuscript, 1904–5

Watercolor and graphite

The National Trust: Hill Top and Beatrix Potter Collection

© National Trust / Robert Thrift

Philip: What follows is a reading from Appley Dapply’s Nursery Rhymes, read by the actor Robert Webb:

Appley Dapply, a little brown mouse, goes to the cupboard in somebody's house. In somebody's cupboard, there's everything nice: cake, cheese, jam, biscuits, all charming for mice. Appley Dapply has little sharp eyes and Appley Dapply is so fond of pies.

Now, who is this knocking at Cottontail's door? Tap tap-it, tap tap-it; she's heard it before? And when she peeps out, there is nobody there but a present of carrots put down on the stair. Hark! I hear it again! Tap tap tap-it, tap tap-it. Why, I really believe it's a little black rabbit.

Old Mr. Pricklepin has never a cushion to stick his pins in. His nose is black and his beard is grey, and he lives in an ash stump over the way.

You know the old woman who lived in a shoe and had so many children, she didn't know what to do? I think if she lived in a little shoe house, that little old woman was surely a mouse.

Sheep

Beatrix with Tom Storey and prize-winning sheep Water Lily at the Eskdale Show, September 26, 1930

Published by the British Photo Press

© National Trust / Robert Thrift

In this photograph Beatrix holds an award for Best Herdwick ewe, won by her at the Fells and Dales Association Show at Eskdale in 1930. The sheep’s name was Water Lily, and the man holding her is Tom Storey, a local shepherd Beatrix hired to help her breed champion sheep. The parish of Eskdale is located about an hour west from Beatrix’s farmhouse at Hill Top.

She first learned of the importance of the Lake District Herdwicks in 1897 from Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, the aptly named “Defender of the Lakes.” Rawnsley was keen to preserve the breed and helped establish the Herdwick Sheep Association in 1899. In 1907, two years after Beatrix purchased Hill Top farm, she had established her own flock of Herdwicks—sixteen in all, with a sheep dog, Kep, to guard them. Her interest in the competitive showing of Herdwick ewes would develop as her flock expanded in size.

Herdwicks are remarkable animals. As described by one of Beatrix Potter’s biographers, Linda Lear, “they can survive the harsh climate on the short herbage of the high fells, and have been known to stay alive buried in snow for weeks, sometimes eating their own wool, sustained by its lanolin content.” Despite their hardiness, the breed’s population was threatened in Beatrix’s day and again faced extinction in 2001, following an outbreak of foot and mouth disease. But there are farmers today still dedicated to saving the Herdwicks and increasing their numbers.

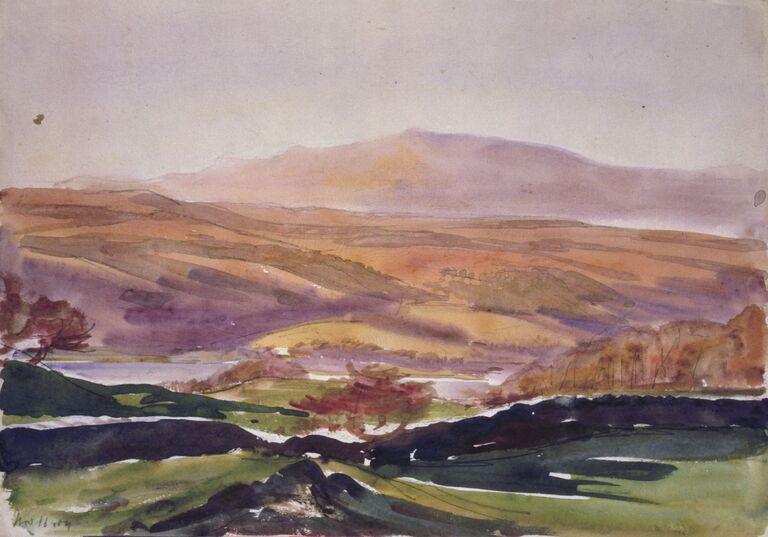

A Living Legacy

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

Monk Coniston Moor, drawn “7.00 morn,” November 16, 1909

Watercolor and graphite

V&A: Linder Bequest BP.1057

Image courtesy of Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

One of Beatrix Potter’s greatest legacies is the land she bequeathed to the UK’s National Trust upon her death in 1943. The Trust described it as “The Greatest Ever Lakeland Gift,” comprising over four thousand acres, fourteen working farms, and sixty separate properties. Beatrix stipulated that Herdwick sheep flocks be preserved on much of this land, and her transformative gift encouraged other benefactors to donate funds to the National Trust, leading, in 1951, to the formation of the Lake District National Park. Today the National Trust, as Europe’s largest conservation charity, continues this work and follows a mission, in their words, “to look after nature, beauty and history for everyone to enjoy.”

The vestiges of Beatrix Potter’s life and work—her drawings, letters, and personal effects—are preserved in the holdings of several cultural institutions: her drawings of fungi at the Armitt Museum and Library in the Lake District, her picture letters at research libraries including the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton University and the Morgan, and vast collections of watercolors, drawings, and correspondence at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, formed by collectors including Leslie Linder and Joan Duke. Beatrix’s husband William ensured that Hill Top farmhouse would be carefully preserved for the public’s enjoyment and become a place to see her original artwork. Until 1970, when a dedicated gallery opened in a nearby town, visitors could actually see these drawings at Hill Top. Today, the farmhouse is a pilgrimage site for fans of Beatrix’s books from around the world.

The “unchanging world of realism and romance,” as Beatrix described the countryside late in life, was an endless source of inspiration for her books. And these beloved tales, rooted in the natural world, continue to find new readers and new resonances across the globe today.