Morgan’s Bibles: Splendor in Scripture

The Bible has been a driving force of religion, art, and literature in the Western world. Few books have demonstrated the power of the printed word as vividly as scripture—a mark of faith, an object of veneration, a formative influence on language and culture. For J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), collecting Bibles was a way to express his religious convictions and to explore his interests in archaeological artifacts, illuminated manuscripts, decorative arts, drawings, and early printed books. He acquired every object displayed here except a few ancillary documents that belonged to members of his family. Morgan appreciated magnificence in all forms of artistic expression. This exhibition includes masterpieces in mediums as diverse as clay, papyrus, parchment, embroidery, champlevé enamel, repoussé gold, carved ivory, and maiolica. Through his collection we can see how biblical texts have been enshrined in luxury articles for the greater glory of liturgy and ritual—and how they have been disseminated in subversive translations cheaply produced for popular consumption. Morgan’s holdings show the interpretative agendas of church and state, often matters of life and death during debates about the primacy of Holy Writ. Whether intended for public display or private devotion, his books and artworks are treasures of the human spirit attesting to its power of imagination, strength of convictions, quest for meaning, and capacity for wonder.

Morgan’s Bibles: Splendor in Scripture is made possible by the Johansson Family Foundation, the Lucy Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund, the B. H. Breslauer Foundation, and Mr. G. Scott Clemons and Ms. Karyn Joaquino, with support from T. Kimball Brooker, the Achelis & Bodman Foundation, Martha J. Fleischman, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the Themis Anastasia Brown Fund, Roland and Mary Ann Folter, Susan and Eugene Flamm, and Jonathan and Megumi Hill.

Origin Stories

Mesopotamia, First Dynasty of Babylon, reign of King Ammi-saduqa (ca. 1646–1626 BC)

Clay

114 x 90 mm

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan between 1898 and 1908.

Sidney Babcock, Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen Curator of Ancient Western Asian Seals and Tablets

The earliest known writing system was developed in southern Mesopotamia sometime during the middle of the fourth millennium B.C., when a system to keep track of the distribution of resources, such as produce and livestock, became an economic necessity. Using what they had at hand, the Mesopotamians took reeds from the riverbanks and adapted them as tools to impress into clay wedge-shaped marks that were then assigned meanings. This was an intellectual achievement that amounted to nothing less than the invention of writing. Cuneiform, from the Latin word cuneus, meaning “wedge,” evolved into a full-fledged, syllable-based writing system that was used for over three thousand years.

This precious fragment of a tablet is the earliest known version in the Akkadian language of the story of the Great Flood, familiar to many from the Christian Bible. The epic begins when the gods create man, though they soon tire of him and decide to destroy all of mankind. The god Enki (Ea) tells the mortal Atrahasis of the impending flood and instructs him to build an ark. With over 1200 lines, the story filled three tablets. The Morgan fragment, from the second tablet, preserves a unique statement with the work’s title—“When Gods Were Men”—as well as the name of the scribe and the place and date on which he copied it.

Translated into modern English, one passage reads:

The Flood roared like a bull,

Like a wild ass screaming the winds

The darkness was total, there was no sun…

For seven days and seven nights

The torrent, storm, and flood came on…

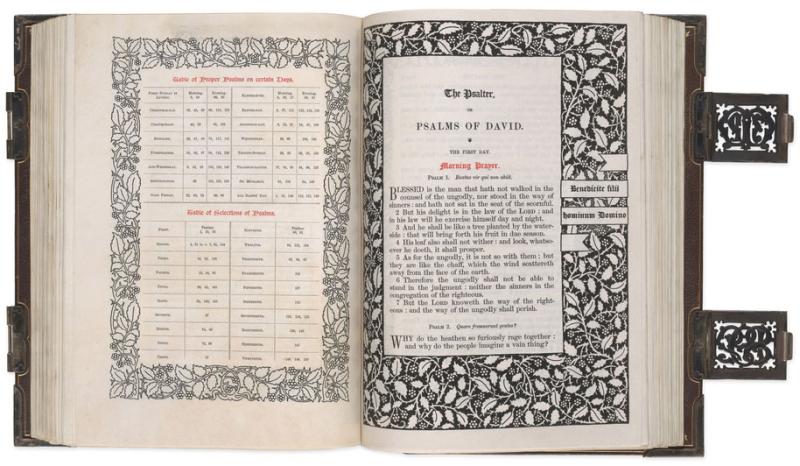

The Episcopal Church

The Book of common prayer and administration of the sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the Church according to the use of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America : together with the Psalter or Psalms of David.

New York : Printed for the Committee [by the De Vinne Press], MDCCCXCIII

Gift of Friends of Mr. Morgan, 1894. PML 5499

Rev. Jacob Smith, St. George’s Episcopal Church:

As a devout Episcopalian, Morgan held a deep reverence for the Bible. It was an anchor for his steadfast belief in people’s character as their defining quality. He was an active parishioner of St. George’s Episcopal Church, funding projects for the Church and using his status to shape major decisions.

Pierpont Morgan’s grandfather and namesake, the Reverend John Pierpont, embraced Unitarianism and became a prominent advocate for the growing antislavery movement; he invoked the Bible to champion the cause of freedom. Reverend John Pierpont had become a fixture in the religious milieu of the Northeast during the mid-nineteenth century. Influential figures from the Concord Transcendentalist movement wove Christian principles into their impassioned speeches during solemn John Brown memorial gatherings. In a town hall meeting on December 2, 1859, they recited passages from Acts and Matthew complete with harmonious melodies, heartfelt prayers, and the poignant last words of John Brown. One of the deeply resonant hymns that resonated during the John Brown Memorial Service was James Montgomery’s soul-stirring Methodist hymn, “Go the Grave in Thy Glorious Prime,” evoking a profound sense of reverence and commemoration. It reads:

Go to the grave in all thy glorious prime,

In full activity of zeal and power;

A Christian cannot die before his time;

The Lord's appointment is the servant's hour.

Go to the grave: at noon from labour cease;

Rest on thy sheaves, thy harvest task is done;

Come from the heat of battle, and in peace,

Soldier! go home; with thee the fight is won.

Go to the grave, for there thy Saviour lay

In death's embraces, ere He rose on high;

And all the ransomed, by that narrow way,

Pass to eternal life beyond the sky.

Go to the grave? No, take thy seat above!

Be thy pure spirit present with the Lord,

Where thou for faith and hope hast perfect love,

And open vision for the written word.

The Bible in Wampanoag

The Holy Bible : containing the Old Testament and the New / translated into the Indian language, and ordered to be printed by the Commissioners of the United Colonies in New-England, at the charge, and with the consent of the Corporation in England for the Propagation of the Gospel amongst the Indians in New-England.

Purchased with the Irwin collection, 1900.

PML 5440

Jesse Erickson:

The printing press used for the Algonquin Bible, Samuel Green’s press, was the first known in the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America, arriving from England in 1638. Elizabeth Glover, the former owner of the press and widow of Reverend Joseph Glover, accompanied it to the shores of the “New World.” Located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the press found its place there, eventually becoming an early precursor to Harvard University Press.

By the time the Algonquin Bible was printed, Samuel Green had assumed responsibility for the press. Green sought assistance from Marmaduke Johnson, an experienced English printer who later established Boston’s second printing press. This collaborative team brought the Algonquian Bible to fruition.

Making Acquisitions

Coded Telegram

MS M.1 coded telegram

Jesse Erickson:

One of the greatest treasures of the Morgan Library, the Lindau Gospels, was one of Pierpont Morgan’s best-known acquisitions. Approaching the Lindau Gospels, it is easy to be captivated by the opulence of its enchanting covers.

Junius Morgan, Pierpont Morgan’s nephew, was enormously instrumental in elevating Morgan’s collecting. On this occasion he sent a cable to his uncle when he chanced upon an extraordinary opportunity to acquire the manuscript. Utilizing a coded message, he relayed to his uncle the marvels of the Lindau Gospels. Remarkably, it was available for £10,000. Undaunted, Morgan seized the manuscript and orchestrated its journey to New York. International communications from Morgan skillfully employed encryption, safeguarding the secrecy of his financial transactions. Here is the coded text in its entirety.

Tambales solmites [can obtain for you] famous gospels ninth or tenth centuries gold and jewel binding of time treasure of great value stomachers [and interest] reported unequalled england or france ashburnhams cogete [price] asked rebullir [ £10,000] am told been [£8,000] parsees triturar [strongly recommend] mailing full description.

Three Crosses

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1606-1669

Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves: 'The Three Crosses'

RvR 122

Rembrandt, the innovative printmaker, constantly pushed boundaries in his pursuit of distinctive tonal effects and dramatic portrayals. He combined etching, drypoint, and engraving, sometimes favoring drypoint alone. His exploration extended to paper choices, recognizing how texture and tone impacted the final piece, enhancing desired effects.

“The Three Crosses” is a striking engraving from 1653. Depicting Christ’s crucifixion between thieves, the composition includes mourning figures and conversing men. Rembrandt ingeniously incorporated references to famous artworks. This print highlights Rembrandt’s mastery, executed with exceptional skill and vision using drypoint and burin techniques.

Nadine Orenstein:

What Rembrandt does, that I find rather amazing is, he really sums up so much about humanity. It’s a familiar story that expresses universal emotion. Rembrandt looked at people all around him, all the time, was always sketching. How people stand; how people faint; how people move their head as opposed to the rest of their body. That’s what he introduces into a biblical subject. Rembrandt is able in just a few lines to show emotion in its most universal and simplest forms. From simple figures, bathed in very bright light—he shows them just in outline—to very detailed figures in the darkness. He’s playing with this alternation of dark and light. Rembrandt printed it on vellum, a material that keeps the ink hovering on the surface, and that beefs up the richness of the image. Rembrandt is making changes right on the surface. First he put Christ’s foot straight down, then he put this head on top. When I look at it I see the artist at work. Every single impression around the world (and there’s only maybe fifteen or so of these in existence) looks slightly different, so he’s really making a painted print.

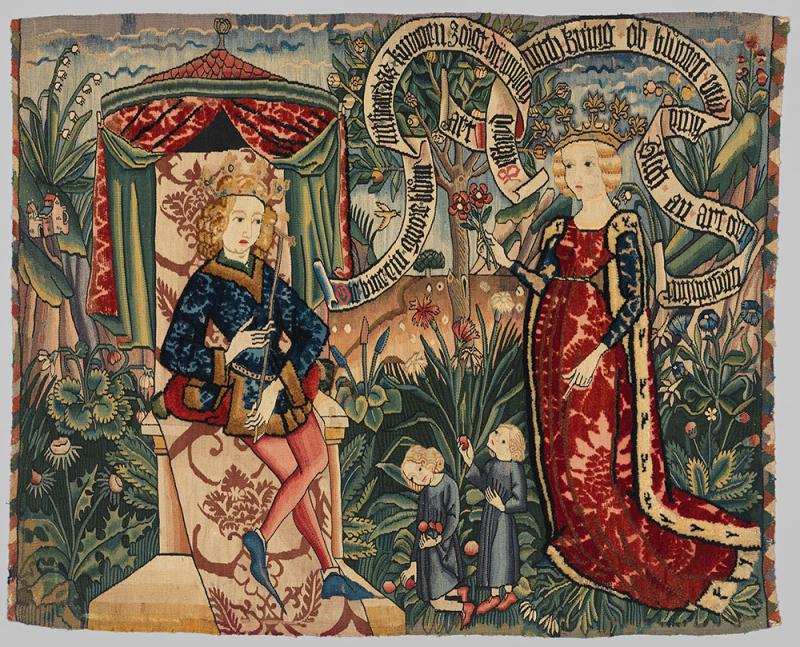

Weaving Riddles

Queen of Sheba Tapestry

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 1971.43.

The Cloisters Collection, 1971.

Jesse Erickson:

This captivating tapestry depicting “Solomon and Sheba” is steeped in legend and the riddles surrounding it. After Morgan’s passing in 1913, his extensive collection was dispersed and the “Solomon and Sheba” tapestry was acquired by the firm of French and Company. Over time, it found its way to W. Hinckle Smith of Philadelphia before eventually being acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dating back to the late fifteenth century, this German Upper Rhenish tapestry, possibly from Alsace, is small in size and exceptionally well-preserved.

One aspect of “Solomon and Sheba” revolves around the riddles depicted in the tapestry. It is believed that the core of the riddles draws from myths connected to Semiramis, the legendary queen regent of the Assyrian Empire. Recent scholarship into the riddles’ origins, moreover, suggests that they can be traced to Jewish sources that influenced early Arabic-Persian versions. The tapestry’s scene, featuring Solomon seated on a throne accompanied by Sheba, with children gathering apples between them, is rich in symbolism. Sheba says, “Tell me, king, if flowers and children are unlike, or unlike in their kind.” Solomon has to identify which is the real flower, which one is artificial. He has to identify which of the identically dressed children is a boy, which is a girl. He solves the first riddle by releasing a bee with the expectation that the bee would recognize the scent of the real flower. The second riddle is solved by throwing apples before the children knowing that the girl will kneel down to gather apples in her robe and that the boy will pick them up in his hands. Here Solomon says, “The bee does not miss a real flower. Kneeling shows the female sex.”

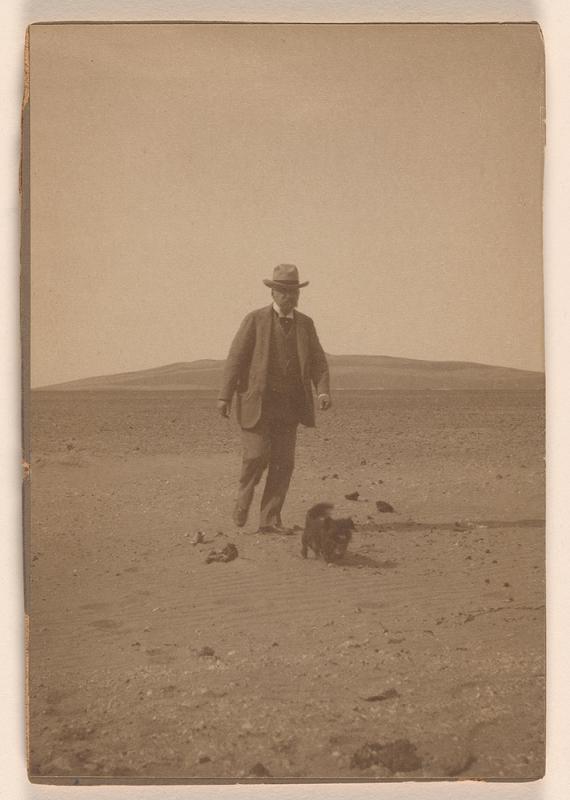

Expeditions

J. Pierpont Morgan and the dog Shun

Egypt between ca. 1900 and 1913

Archives of the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. ARC 3018.2.2

Jesse Erickson:

In 1909 Morgan and his companions ventured into Egypt for an expedition, an annual excursion. Morgan saw these places as evidencing a kind of biblical literalism. Their journey led them to the Monastery of Saint Jeremiah in Saqqara, nestled near the renowned pyramids of Giza. The complex where the impressive church was situated included, among other notable architectural treasures, an archaic type of pulpit known as an ambon.

Their expedition, however, did not stop there. As recounted in Jean Strouse’s biography, Morgan: American Financier, the next month had the small crew of explorers embarking on a large houseboat called a dahabiyeh. They traversed thirty-five miles along the Nile to reach the excavations at Lisht. Led by Albert Lythgoe, the team witnessed hundreds of workers clearing debris and sand at the pyramid of Senwosret I. The gradual reveal of the ancient remains dating back to almost 2000 BC left a lasting impression on Morgan.

The party later ventured to the Great Oasis at Khargeh where they took in the views and scenes of the historic landscape. Further unearthing Hibis temple, the expedition’s archaeologists shed more light on the early Christian era at Khargeh. The site’s tomb-chapels were adorned with frescoes depicting biblical scenes and houses that dated back to the fourth century AD. Morgan expressed his satisfaction to Lythgoe, confessing that he never anticipated witnessing such a wealth of intriguing artifacts and historical marvels.

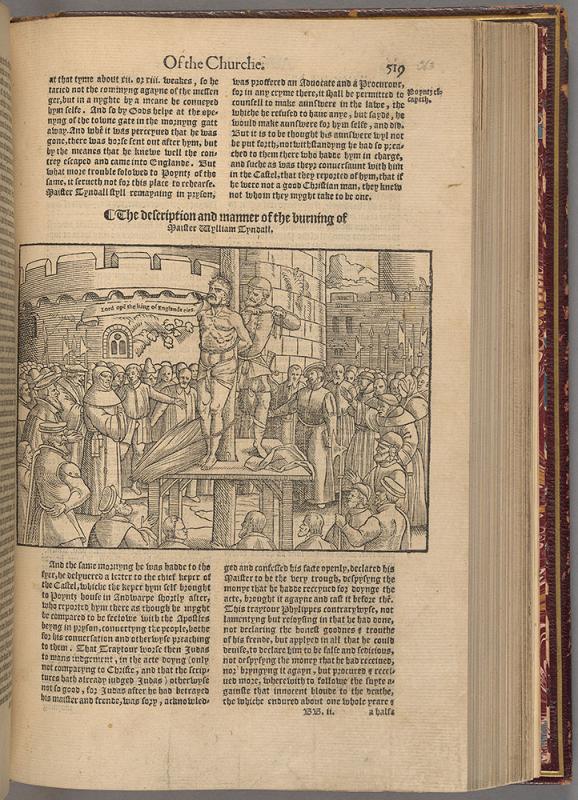

Martyrdom

Actes and monuments ... touching matters of the church ..., Martyrdom of Tyndale, volume one of Foxe's Martyrs (1563) on page 519

Foxe, John, 1516-1587.

PML 7817-18

Jesse Erickson:

William Tyndale was an important figure in the history of Bible translation. In the early sixteenth century, Tyndale undertook the monumental task of producing an improved English translation of the Bible in English, following in the footsteps of Martin Luther and other influential translators of the time. His translations drew from Greek and Hebrew texts, resulting in powerful prose that can still be recognized in the King James Version.

Tyndale’s work, however, faced significant opposition. Tyndale made enemies with King Henry VIII, for instance, when he argued against his intent to seek an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Henry condemned Tyndale’s translations leading to their prohibition in England. Undeterred, Tyndale resorted to printing his Bible abroad and having it smuggled into his home country, defying the censors. The first edition of his translation’s Old Testament claimed to be the work of Hans Lufft, a printer known for his Luther Bibles, perhaps as a playful act of defiance.

Despite the risks involved, Tyndale persevered, releasing revised editions with thought-provoking exegesis that challenged established interpretations. His notes reflected his commitment to Protestant theology. The English authorities made attempts to negotiate with him, but these negotiations ultimately failed. Betrayed by the aristocratic Comptroller of the Customs, Henry Phillips, Tyndale was captured in Antwerp and subjected to a trial that led to his condemnation and, in 1536, his execution. Just before his death, he uttered the poignant words, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes,” prominently featured in a woodcut that appeared in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. A selection from this work reads:

So in like manner this traitor Philipps… with bringing master Tyndale into the hands of God’s enemies, took money of him under a color of borrowing, and put it into his bag, and then incontinent went his way therewith, and came with his company of soldiers which laid hands upon him as before, and led him. And about one whole year and a half after, he was put to death at Filford with fire.

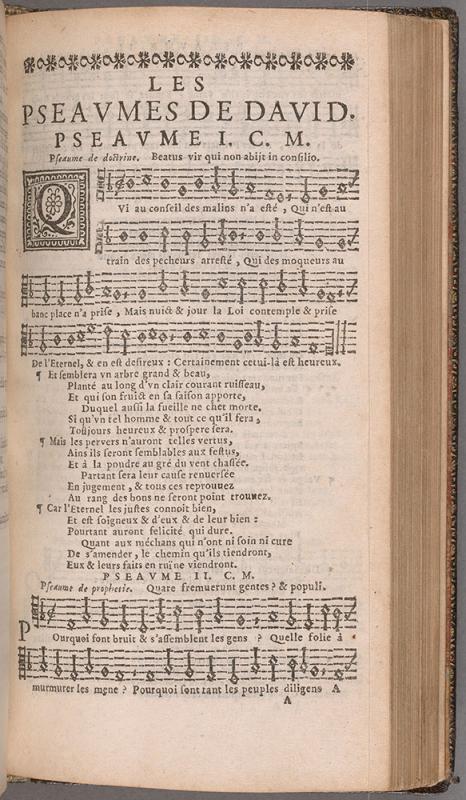

Music of the New Testament

Le Nouveau Testament ..., Second sequence, pi 2 verso - A1 recto, "Les Pseaumes de David"

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1907.

PML 16052

Jesse Erickson:

Psalmody benefits from a continuing legacy left by French and English Protestants and their melodic expressions of faith. In the sixteenth century, John Calvin grasped the profound spiritual power of music, particularly the captivating practice of setting psalms to melodies. Calvin believed that these songs should not be limited to the choir, but rather, everyone should engage in their melodic embrace. He held that through song, one could invoke and praise God with heightened fervor and devotion.

Calvinist psalmody is associated with the metrical psalter, a form of the tradition wherein verse translation of the Book of Psalms is entirely intended for church hymns. Such translations are further characterized by their harmonic arrangements, which are restricted to vocal performance in the most conservative examples. Among the examples of these compositions, you can discover the music for Psalm 1, sung here by the Gesualdo Consort, which is preserved within the pages of the 1647 Charenton New Testament.

Offered by the Parisian bookseller and printer Pierre Des Hayes, Charenton proved to be somewhat of a refuge and marketplace for French Protestants after the Edict of Nantes in 1598 placed restrictions on where the reformed could erect their places of worship. Some of the savvier Parisian booksellers and printers kept their Paris addresses, but set up shop in the area to cater specifically to this community. Des Hayes appears to have had familial connections with the Celliers, further pointing to a Calvinist connection. Notably, Antoine Cellier of Paris and Charenton was the only printer to produce Huguenot historical calendars after 1661.

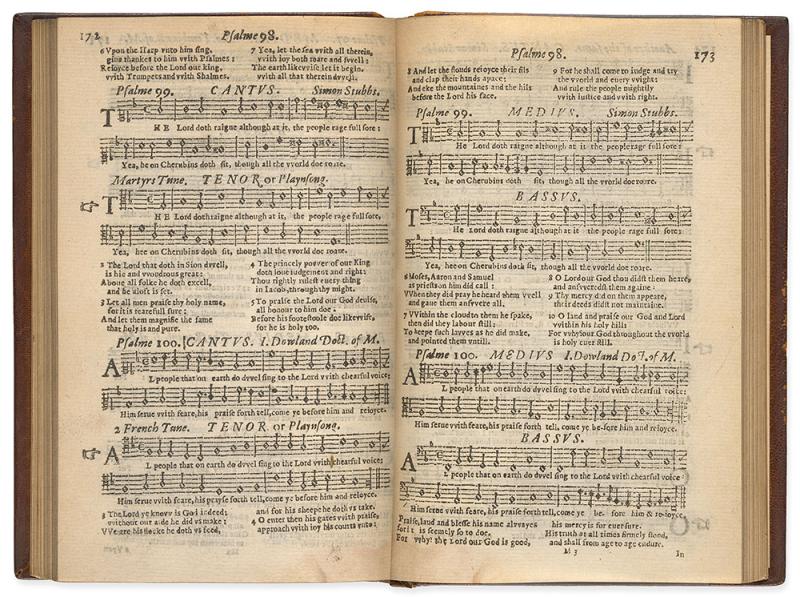

Music of the Old Testament

The whole booke of psalmes: with the hymnes evangelicall, and songs spirituall. Composed into 4. parts by sundry authors, with such seuerall tunes as haue beene, and are vsually sung in England, Scotland, Wales, Germany, Italy, France, and the Nether-lands: neuer as yet before in one volumne published. Also: 1 A briefe abstract of the prayse, efficacie, and vertue of the psalmes. 2 That all clarkes of churches may know what tune each proper psalme may be sung to. Newly corrected and enlarged by Tho: Rauenscroft Bachelar of Musicke.

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907.

PML 15187

Jesse Erickson:

It was with meticulous care that Thomas Ravenscroft edited the definitive English psalter, ensuring the inclusion of beloved classics like the “Old One Hundredth.” As you take in the harmonization crafted by the skilled lutenist and composer John Dowland, take a moment to recognize the melodic foundation established with Calvin’s gifted protégé, Loys Bourgeois. In Ravenscroft’s Whole Book of Psalmes, a collection of four-part settings, the psalms were presented with the tune placed in the tenor voice, offering a harmonious symphony of praise.

Ravenscroft’s psalter of 1621 documents his commitment to present the psalms in rich four-part harmonies. Each voice played a vital role, with the tune resounding from the tenor, creating a cohesive musical experience. These harmonious settings invite you to explore the lasting beauty and power of the psalms, each note resonating with profound meaning and devotion. The symphony of voices signifies a belief in the transformative power of sacred music. Here is a version of the music sung by the Calvin Choir.

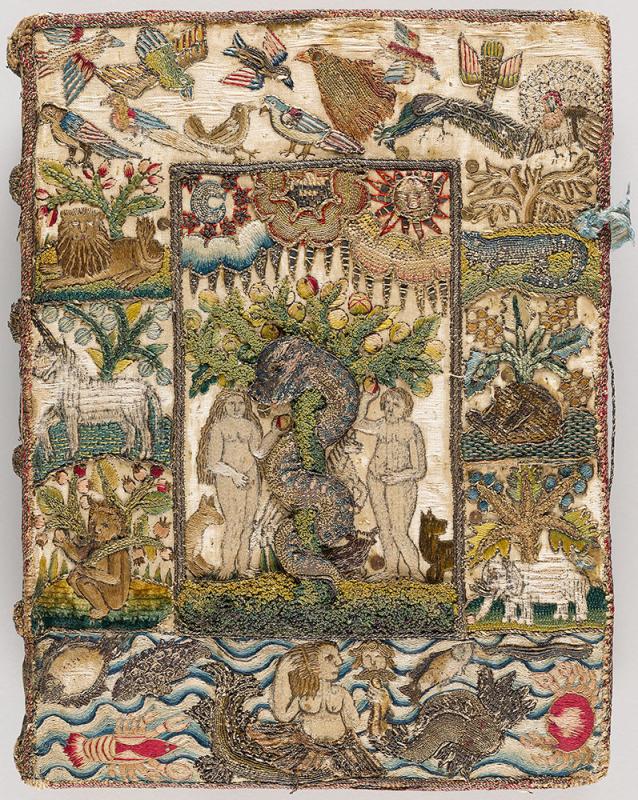

Weaving Bindings

The Bible : that is, the Holy Scriptures conteined in the Old and New Testament ...

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1910.

PML 17197.1

Jesse Erickson:

Here we have a meticulously crafted piece by Anne Cornwallis Leigh, a member of the Staffordshire gentry, dating back to around 1640.

In a May 1910 letter from F. A. Wheeler, the bookseller responsible for several Bibles in Morgan’s collection, to the Morgan’s first director, Belle da Costa Greene, Wheeler expresses great admiration for this piece. The letter reads:

I am sending you by this mail the photographs of the magnificent Cornwallis family Bible 1599 which Mr. Gordon Duff describes in a letter to me as ‘probably one of the finest specimens of an English embroidered cover now in existence.’ The volume is almost as fresh as the day it was bound … Luckily it was in a little ‘mixed’ sale and I had to give only £250 to secure it. I shall hope to get £500 for it unless Mr. Morgan takes it. (F. A. Wheeler to Belle da Costa Greene, 4 May 1910).

Drawing a Miracle

Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in 1909.

I, 21

John Bidwell:

Like much of the artwork in the exhibition, Perino del Vaga’s “Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes” was the product of aristocratic patronage. In this case the patron was Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III, son of the Duke of Parma. He held high offices in the church, the proceeds of which helped to finance an immense art collection, including the sumptuous illuminated Farnese Hours now at the Morgan. He employed the renowned medalist Giovanni Bernardi on several projects sacred and secular such as a crucifixion scene in rock crystal and a silver chest adorned with mythological subjects. He commissioned this drawing to serve as a model for one of a series of rock-crystal plaques engraved by Bernardi. Vasari described the commission in detail: For two candelabras of silver he [Bernardi] engraved six round crystals. In the first is the Centurion praying Christ that He should heal his son, in the second the Pool of Bethesda, in the third the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, in the fourth the Miracle of the five loaves and two fishes, in the fifth the scene of Christ driving the traders from the Temple, and in the last the Raising of Lazarus; and all were exquisite. Five of the plaques have survived as well as some of Perino’s drawings, two of which are at the Morgan, this one and the Pool of Bethesda.

“A Child is Born”

Christmas Day, recto Gradual cuttings (M.653.1–5). Florence, Italy, 1392–1399.

The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.653.1.

John Bidwell:

The immense gradual illuminated by Silvestro dei Gherarducci must have extended to several volumes. He and other artists worked on this project for more than a hundred years and never finished it. This cutting may have come from a volume containing the music for a portion of the liturgical year comprising the feasts with a fixed date such as Christmas; other volumes contained the music for the movable feasts such as Easter and Pentecost. The text for the Christmas introit comes from Isaiah 9:16, perhaps best known to English speakers from the “for unto us a child is born” passage in Handel’s Messiah. Here is the introit sung by the Choir of the Ascension.

Roman Rites

Gradual

Italy, Florence, 1392-1399

MS M.653 no. 5 (I.15)

John Bidwell:

The musical notation in these two gradual leaves is based on a system traditionally ascribed to the eleventh-century Benedictine monk Guido of Arezzo. Changes in pitch and duration are indicated by the square-shaped notes, called neumes, placed on a four-line staff. The topmost line begins with an f-clef indicating the location of fa in the do-re-mi scale, also thought to have been devised by Guido of Arezzo. Here is the introit for Epiphany sung by the Edmundite Novices.