Uncommon Denominator: Nina Katchadourian at the Morgan

Nina Katchadourian (born 1968) is a multimedia artist based in New York and Berlin. She grew up in California and spent summers on Pörtö, a small island group in southern Finland. Her mother comes from Finland’s Swedish-speaking minority and grew up in Helsinki; her Armenian father was raised in Beirut. Using photography, collage, performance, video, and other idioms, Katchadourian often arranges encounters—with nature, everyday life, or systems of knowledge—that induce what she calls “useful and revealing disorientation.” She wields humor as a strategy and conducts research through committed, serious forms of play.

For the exhibition Uncommon Denominator, the artist selected objects from the Morgan’s holdings and sequenced them with her own works and with artifacts from her family. Katchadourian first encountered many of the Morgan collection objects through show-and-tell conversations with staff members who answered her request to tell her about a piece they had always hoped to see exhibited.

The exhibition’s order obeys the artist’s expansive, imaginative logic, touching on themes that include cartography, celestial events, repair, rearrangement, concealment, record-keeping, handshakes, plants, animals, and perpetual recurrence. Katchadourian has added her commentary throughout the gallery, but inevitably every viewer will read the object-to-object connections in their own way and arrive at unique questions. “Art is a good place to practice the craft of looking and listening closely,” she notes. “Through my work, I hope to infect people with a certain rigorous attentiveness.”

This exhibition is made possible by the Charles E. Pierce Jr. Fund for Exhibitions, Richard and Ronay Menschel, the Alturas Foundation, and the Sakana Foundation. Support is provided by Wanda Kownacki, Emily MF Korteweg, Nicole Avril and Dan Gelfland, and Corina Larkin and Nigel Dawn, with assistance from Martin Z. Margulies, Megan and Paul Segre, and Larry Kauvar.

Maps, I

Nina Katchadourian: When I started making art, the very first things I made were maps and one of the reasons I got interested in maps, I used to say, is because they look true. You can work with the form of a map and it comes with a kind of authority that makes people believe what they see there. The moss maps were a series of photographs I took because I recognized in these lichen forms that were growing on a big granite hill, I recognized patches of lichen that reminded me of actual places in the world. And making these photographs became like a kind of geography Rorschach, where I roved around on the hill and looked for formations that I thought resembled continents, some of them more closely than others.

The first map I ever made though was a world map, a paper map that I cut apart and carefully rearranged so that all the countries were suddenly in new relationships to one another. And a few years later I worked with the same paper map, but this time to make World Map II, I cut the map into long thin horizontal fragments and then rearranged those, creating what I thought about at the time as a sort of analog digital image. So this show begins and ends on this theme of maps. At the beginning we have the Moss Maps and World Map, and on the other end of the show you'll find a few other maps, both from the Morgan's collection and maps that I've made myself that prove that I've really never stopped thinking about maps. There may also be an autobiographical reason or a more personal reason that I'm interested in maps, and that's because my own family and background is a little bit like a rearranged world map.

Connections

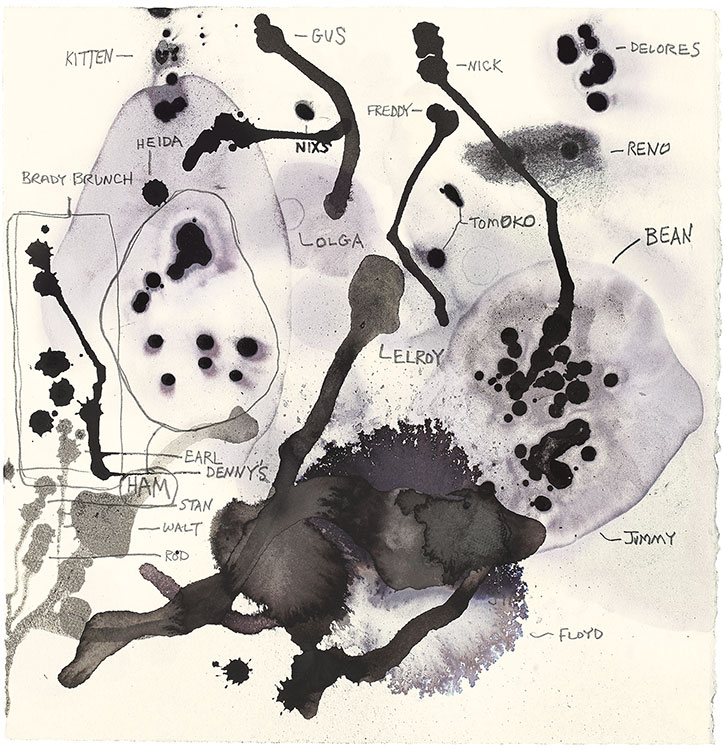

Al Taylor (American, 1948–1999)

Pet Names, 1991

Gouache, ink, xerographic toner fixed with solvent, and graphite

Gift of Debbie Taylor; 2020.39

© The Estate of Al Taylor. Photography by Glenn Steigelman

Nina Katchadourian: In Al Taylor's drawing called Pet Names, he has made what seems to be rather random drips and dribbles and then labeled these with the names of various neighborhood dogs. So there's sort of one kind of marking and then a, a kind of animal kind of marking that, that meet up in this drawing. But they're also emanations of a sort, and I think that for me is what connects them to the other two works here, this image of witches from the Ames album and then an image I've made called Prince Charming. In those last two images, there's a kind of emanation or leakage of energy, or force of energy, moving between these elements in the picture, work like a kind of charm or curse or spell being cast. So the attractions that we see here might be, you could say, both of a natural and a supernatural type.

Prince Charming is made from an image that I saw in an inflight magazine when I was on a plane once and I poured sugar onto that page and I shaped the sugar so that it appeared that these two pilots passing one another were winking at one another. This group also has in common markings and signals cast out into the world that are perhaps perceptible to some, but not to all. For the dogs leaving markings, perhaps it's only other dogs that perceive those, those messages and similarly for the witches, and similarly for the pilots who are passing each other here and communicating something that perhaps only they are privy to. There are connections that are only visible for a moment, like a handshake where two things come together for an instant, touch, and then separate. And as the show's very title suggests Uncommon Denominator, it might be about looking for a connection that isn't the, the very first and most obvious one. So, I've tried to find instances of things that join up together perhaps for a moment, perhaps visibly, perhaps less so. And in Saul Steinberg's drawing old couples, it's also a wonderful collection of things that, that seem to belong together that, that might be together in ways that we see all the time, but haven't identified as, as a couple per se, like a knife and a fork, or, or the intersection of two streets. So they belong together and, and yet they're kind of together all the time right in front of us.

Plants

Nina Katchadourian: Plants can sneak up on you and I think there, there are several examples of that in this group. They move slowly, you don't see 'em coming, but eventually they will potentially eat you alive. I wanted to put all these things together in this group to think about the ways that plants sometimes have a kind of almost human agency to slowly overtake something else. In both Giant Redwood and the image of two men in a jungle that was taken in India around 1860. The scale of the humans is wildly dwarfed by the scale of the plant life. And, there's something quite humorous about that actually to me, that the, that the people have become shrunken in the face of these much, much bigger and perhaps even threatening plants.

Something else that's going on in this group is about the impulse to preserve plants, the kind of botanist view of, of how you might extract something from its native environment and then preserve that thing by pressing it into a book or by flattening it or reproducing it, collecting it, archiving it.

I made topiary while I was on an airplane on a long flight by using a picture from the inflight magazine of a decorative garden on the shores of Lake Como. And I happened to be eating a bag of fresh green peas. So I stacked up a number of them, placed them on this image, and made this, um, very, very large topiary structure that a number of very, very small people are clustered around, walking around. I spent about a year studying plant structures and then trying to make fake plants from memory. I was not interested in replicating actual plants. I wanted to sort of see if I could residually remember the way that plants tend to be structured. And so looking through stuff in my trash at home or stuff in the trash at the studio, I made an extensive series of fake plants using materials that I then constructed into quite refined plant forms. The one you're looking at here is made from the packaging from a box of frozen beans that I hadn't noticed until I thought, what if I cut that into leaf like shapes and glued them to a piece of wire?

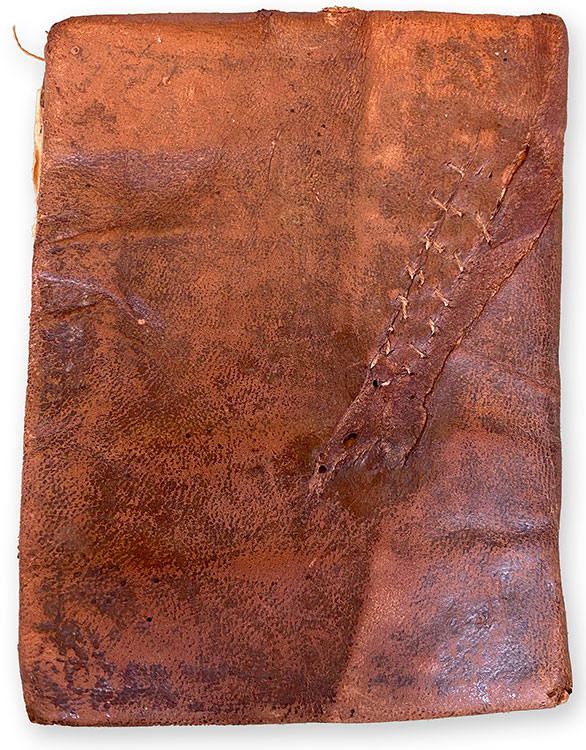

Handheld Objects

Nina Katchadourian: It can be hard to know how to find your way into a collection and the Morgan is a vast place. So one of the strategies I decided to use, which has worked well for me before, is to just start with the question of who's already here and what do they know, and letting the people who have an intimate familiarity with a collection teach me about it. And that was a way into finding a lot of things that I wouldn't have known were at the Morgan. So in that spirit, I invited fifteen different Morgan staff members to sit down with me for a one hour conversation with an object that they had selected. I asked them to choose something that they felt an attachment to that they were excited to show me and to talk about. I've put a few of those things together here and one thing they have in common for me is their small handheld, rather intimately handled quality. The little tiny primer, which you can see by the way it's bound and by the way it’s repaired, has clearly been in somebody's pocket, has clearly been almost read to death and there was something really alluring to me about the way it's been used and preserved. And I like objects that reveal something about how they have been used or how they have lived. You could even say, and the primer is one of those objects for me. You can see by the wear and tear on its cover, by the stitching, by its very design being a small object. It's meant to be in your pocket and meant to be carried around. Its very appearance is sort of, its autobiography. It tells the story of its life and use.

When the curator of ancient seals and tablets brought out this Mesopotamian seal to show me, um, it was one of the most incredible handheld experiences that I had making this show. And I will never forget that he used the word buttery to describe its texture, which is very accurate.

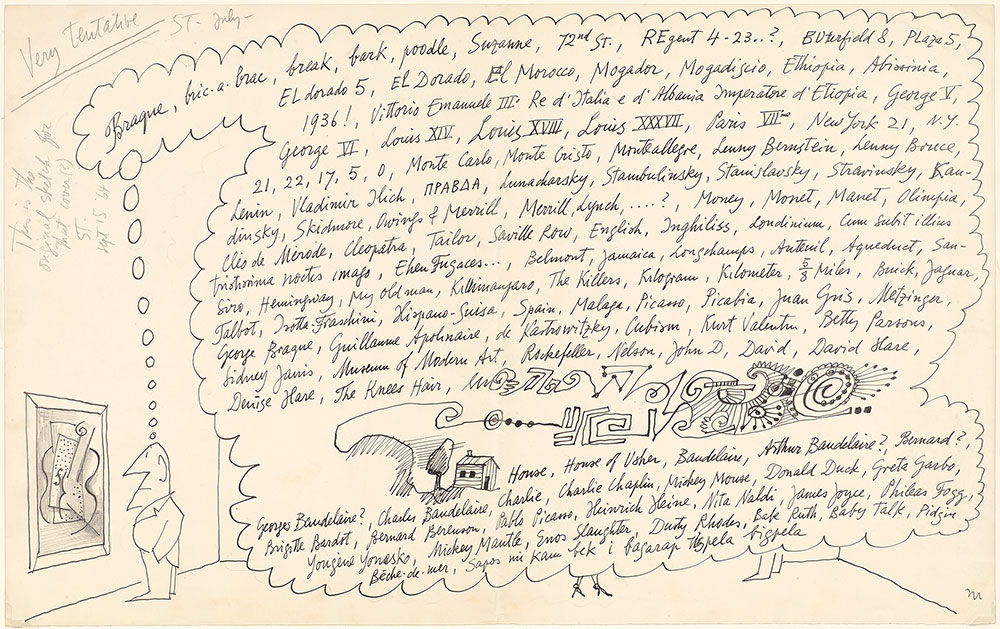

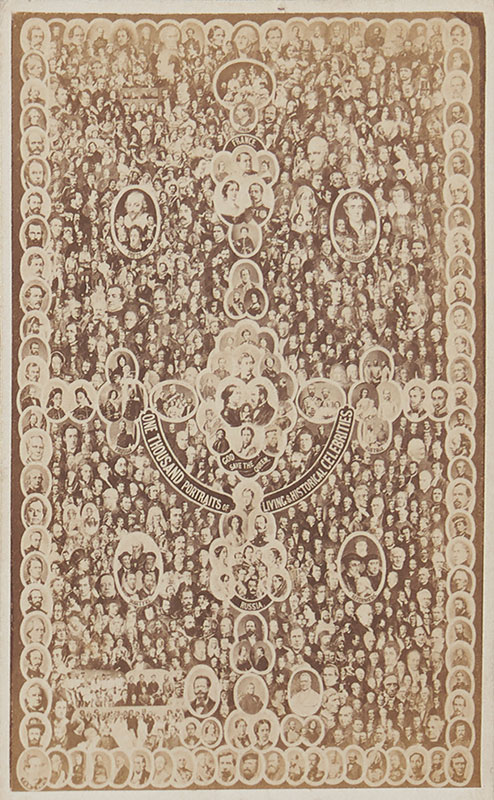

Swarms

I think of this group as being about swarms and the way that on one hand, language can swarm in your head, or one word can lead to another in such rapid succession that suddenly you're many steps away from where you begin. That's what I like about the Steinberg drawing as well as the, the way that one thing leads to another in a way that feels both logical and utterly logical at the same time. There's even a point in this drawing where writing turns into drawing, it just turns into shapes, it turns into scribbles, and then it comes back into kind of what we would call sense.

The other kinds of profusions in this group cross quite a few categories. We have discarded vegetables and Tim Davis's photograph. We have a collection of politicians in the 13th Amendment photograph, and we have celebrities collected in a tiny, tiny, tiny Carte de visite. The irony here, to me being that if you collect a lot of really famous people in one place, suddenly none of them seem very famous. They all seem just like a group of people all over again.

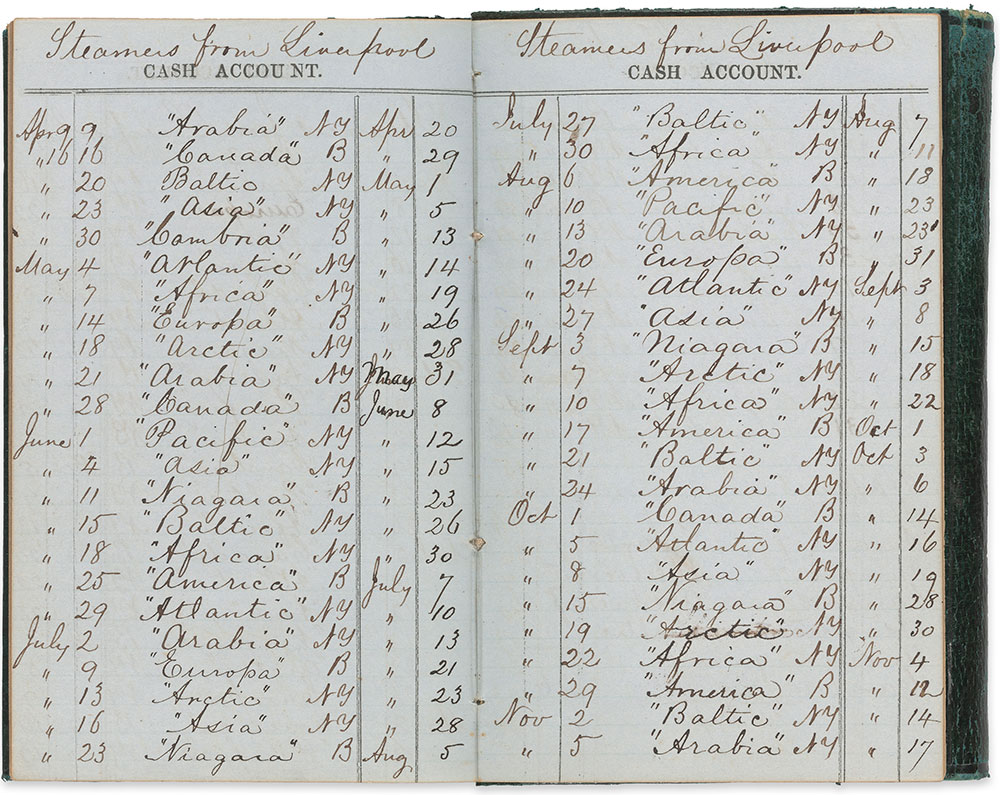

Records

Nina Katchadourian: Quite early in the process of working on this show, I asked to see objects that you could generally describe as being records of things. It's a category I've been very fond of for a long time because of my own propensity for keeping records and I think that habit has been something inherited from my maternal grandfather Lale, who kept all kinds of records, a record of his birdhouse, Inhabitants is one of the objects in this show.

I'm interested in the way people keep records for themselves, but also the way that, that institutions keep records about themselves. I wanted to include records that also had to do with how this institution, the Morgan, has been recording itself and its collection and, and the ways that things in this collection are maintained. Even the personal records in this case are very different kinds of personal: there's Beth Van Hoesen’s journal of her mental health, day by day of, of a yearlong hospitalization that she experienced. There's JP Morgan's teenage journal written in a very organized fountain pen, hand of ships that came in and out of port that he felt compelled to track. And then there are records of my own from around this time: a high school calendar where I was mostly interested in noting daily events at school and concerts that I attended. And a record I called the Beatle Log were for about two years in junior high school. I wrote down every time a Beatle song came on the radio, which station had played it, and what song it was, and also the log book from a whaling ship called the Emily, where every time a whale was caught, it seems a small whale stamp was applied to this page. So you can see the whales as they stack up. I included George Augustus Sala's Commonplace book, not because I necessarily have any idea what it is. He is recording, but the very way he makes the record is so full of care and so full of detail. It seems that obsessiveness in record keeping suggests that there is something worth recording.

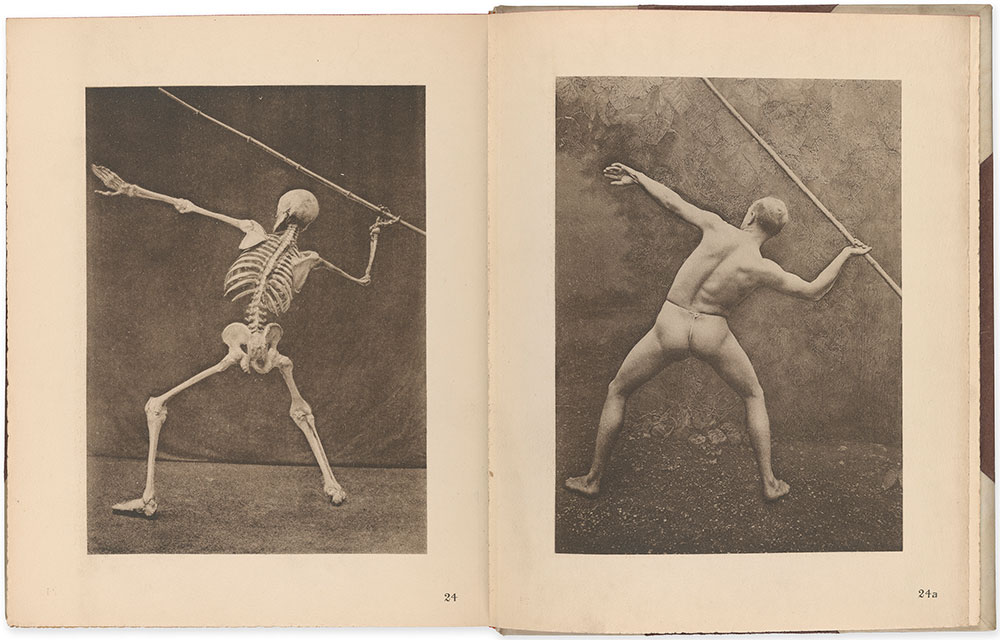

Bodies

Nina Katchadourian: I think there are two things that connect objects in this group that generally have to do with the human body. One is how you might observe it, how you might record it, but also how you might make it strange to yourself by observing it and then changing it. So there are a number of photos here where the body is kind of taken apart and put back together differently. There are also examples of how you might try to see something inside a body, perhaps the impulse to show a man throwing a javelin and also a skeleton. Throwing a javelin, um, is a little bit related to my impulse as a seven-year-old with my best friend to write an anatomy book for the children, by the children, where we too, were really curious about the mechanics of ourselves and what we were constructed of and how those things worked. So in the book that I made when I was seven, there is an attempt to take the whole thing apart and to understand what the component parts might be. Maybe there are these two things happening at the same time, which is that parts of us become more known to ourselves and parts actually just get even more strange.

Holes

When I went to visit the conservation center at the Morgan, I ended up looking at a lot of things like tools or remnants of the conservation process. And one of the most interesting of those was this book, which had correspondence between Walt Whitman and his mother pasted into the book. The letters had been taken out so that they could be conserved properly, but this leftover book with holes in it had been saved as well. What I like is trying to sort of fill in this blank, trying to imagine actually what had been in this book. There's something curious to me about the transparency that this book now has. You can see through the whole book at once. It's a little bit like the photograph of the house here by Shen Wei, where you can see a skeleton of something, and I love these pages that had giant holes missing from them, and it made me think a lot about excision, which is a process I've used a lot in map works of my own, where it's been about extracting something with an Exacto knife from its paper surroundings.

Maps II

Nina Katchadourian: I find myself looking for maps or maybe sometimes just finding maps without looking for them in a lot of situations in daily life and I had been in Paris one summer and was about to cross the street when I looked down and on a metal stanchion pole that had been painted, a lot of the paint had worn away. And from this view I had looking down on it, it suddenly appeared like a very realistic globe with small island-like land masses on it. So I quickly took a picture of it with my cell phone just before I crossed the street. And looking back on it later was struck by how very realistically these landforms appeared. Because of the way the paint has worn out on the stanchion, the land forms had a very dimensional quality to them. And this piece makes me think back to the moss maps and ways that I've sometimes projected a map-like quality onto something in the world that isn't trying to be a map at all.

I deliberately went looking at the Morgan for maps and was very happy when I discovered Betts's Globe, which is described as a portable globe. And although I know it's not really meant to be taken out into the world and opened up and navigated with, I do like imagining someone trying to use it that way.

Ships

Top of the Ernest Irroy champagne bottle used by Louisa Pierpont Morgan (American, 1866–1946) to christen J. Pierpont Morgan’s (American, 1837–1913) steam yacht Corsair III on 12 December 1898, in Newburgh, New York

Morgan Library Archives, Gift of Mrs. Jan Vanheerden, 1997

Nina Katchadourian: Undoubtedly, one of my favorite objects discovered at the Morgan was this broken champagne bottle top. It turns out it had been used to christen Morgan's yacht called Corsair III, and through this broken bottle top I learned the term realia, which is a category of objects in the collection that don't necessarily contain information as such, but still have qualities about them worth preserving. To me, this object also turns a museum into something that feels a little bit more like a domestic home. The way that we sometimes save things that mark important occasions might look like junk to somebody else, but to us, uh, indicates something important that happened. And I'd like moments in a collection where things jump categories a little bit like this. It's located where it is in this exhibition because it's a way into one of the subjects that has been a lifelong fascination for me, which is that of true stories of shipwreck survivors. I imagine the bottle here as a kind of inauguration into a shipwreck story. In this case, the true story of the Robertson family.

Recessions

Interior view of tunnel book A View of the Tunnel under the Thames, as it will Appear When Completed (London: S. E. Gouyn, 1828).

Library Company of Philadelphia

Nina Katchadourian: All of these things in this group for me are, are a little bit about where the 2D and the 3D meet or perhaps get confounded with one another. There are plays here with, with depth hand space, but also to me, a sort of low-tech version of a virtual reality experience where you gaze into something and are brought into a space that envelops you. So what the tunnel book asks you to do, and I think this isn't too different from what virtual reality games might ask you to do, is to forget that you have a body that is engaged in the activity and to be completely within this illusionistic space that is created for you and that you're asked to step into and that you have to take a sort of leap towards believing. What's also fantastic about the tunnel book, and I chose this one out of many other examples, is because it is a tunnel book about a tunnel between two different sides of the River Thames in London.