She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400–2000 B.C.

The first cities in history emerged midway through the fourth millennium BC in Mesopotamia, in present-day Iraq, home to the ancient civilizations of Sumer and Akkad. These cities, where writing was invented and major cult centers were formed, provide us with fascinating visual and textual evidence on the lives of women in complex early societies.

This exhibition focuses on the region’s fundamental developments during the late fourth and third millennia BC, bringing together a comprehensive selection of artworks that capture rich and shifting expressions of women’s lives at the time. These works bear testament to women’s roles in religious contexts as goddesses, priestesses, and worshippers, as well as in social, economic, and political spheres as mothers, workers, and rulers. One particularly remarkable woman who wielded considerable religious and political power was the high priestess and poet Enheduanna (ca. 2300 BC), the first known author in world literature.

The objects that follow exemplify painstaking artistry and striking stylistic variety in the depiction of women, often combining delicately executed naturalism with powerfully expressive stylization. Masterpieces such as the jewelry of Queen Puabi (ca. 2500 BC) represent the earliest perfection of metalworking techniques that are still in use today. These works have withstood millennia, lending us breathtaking insight into an often-overlooked aspect of an ancient patriarchal society: womanhood.

She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia is made possible through the generosity of Jeannette and Jonathan Rosen.

Additional support is provided by an anonymous donor in memory of Dr. Edith Porada, the Andrew W. Mellon Research and Publications Fund, Becky and Tom Fruin, Laurie and David Ying, and by a gift in memory of Max Elghanayan, with assistance from Lauren Belfer and Michael Marissen, and from an anonymous donor.

Cylinder seal with female figures and cows

A pair of resting cows surmounts two mountains indicated by superimposed triangles. Their bodies are rendered with extraordinary attention to detail, manifested in subtle differences in anatomy. In contrast to these depictions, the stylized bodies of the two female figures are reduced to multiple round forms created with a drill. They sit on benches or mats, arms raised and their hair falling down their backs or tied in a bun at their napes. Between each of the humans and animals appears a large pot. This seal represents the preparation of dairy products in early Mesopotamian societies, in which women played an essential role as part of the workforce.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with female figures and cows

Mesopotamia, Sumerian

Late Uruk period, ca. 3300–3000 BC

Green serpentine

The Morgan Library & Museum, Acquired by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1885–1908; Morgan Seal 7

Sidney Babcock: A number of seals from this period demonstrate the vital role of women in the workforce and their contribution to early Mesopotamian society. They made textile, ceramic, and agricultural products. Here, two women seated on benches or mats prepare dairy products. Similar to other seals that feature female figures working, their hair is gathered and pulled away from the face to keep it from obstructing their vision. One notable aspect of this seal is the difference in the way the women and the cows were rendered. While the women’s bodies are formed by round elements drilled into the stone, the cows are illustrated with more detail. Resting upon mountains, their legs are carefully tucked underneath them and the pronounced, smooth curve of their horns is striking. This treatment is a testament to the Mesopotamians’ deep respect for the animals who provide them with sustenance.

Plaster cast of the Uruk Vase

This cast of the Uruk Vase, one of the most celebrated artworks from Mesopotamia, is true to the original, even showing ancient marks of repair. Its carving centers on the sustenance of life in ancient Sumer. Wavy lines in the lowest register indicate water, above which are cultivated plants and domesticated animals. Next, nude men bearing offerings stride toward Inanna or her earthly representative, who stands at the entrance of her temple in the top register. Before her, a male attendant carries a basket; behind him lies a partially preserved depiction of an ornately dressed man, possibly a royal figure. The harmony between such a political leader and Inanna, his patron goddess, preserved the prosperity of the land.

Plaster cast of the Uruk Vase

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Uruk (modern Warka), Eanna Precinct

Late Uruk–Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3300–2900 BC

Plaster cast

Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Original Excavated 1933–34; VAG 001027

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Foto: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Sidney Babcock: The Uruk Vase is one of the most famous artworks from Mesopotamia, and rightly so. Excavated in the temple precinct of Uruk, the most prominent metropolis of the time, it is one of the earliest surviving cult vessels in the world. What makes it unique is its spectacular carving representing the cycle of life in ancient Sumer.

The story begins in the lowest register with wavy lines symbolizing the foundation of all life: water, namely the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. Then cultivated plants and domesticated animals enter, setting the stage for the upper register featuring nude men bearing offerings. The principal scene is at the top: Inanna or her priestess stand before the entrance of her temple. Before her is an offering bearer, who is followed by an only partially-preserved figure, the train of whose garment is held by an attendant. This ornately dressed person must have been the ruler, whose concord with Inanna was crucial for the well-being of the land.

Steps were taken in ancient times to preserve this valuable vase for eternity. This cast from Berlin is true to the original, even showing such ancient marks of restoration above Inanna's head. Following the US-led invasion in 2003, the original vase was looted from the Iraq Museum in Baghdad but recovered a few months later.

Cylinder seal with "priest-king" and altar on the back of a bull

In a boat stands a “priest-king,” the highest-ranking ruler in the first cities, represented with a long beard and a netted skirt revealing the rounded forms of his lower body. He faces a bull supporting a two-tiered altar crowned with reed ring bundles with streamers, symbols of Inanna. Behind him is a wattled structure, possibly standing for a temple facade. Two attendants navigate the boat from the bow and stern, which are adorned with buds. This seal, with a silver knob in the form of a recumbent calf, was buried in the sacred precinct of Inanna in Uruk. Its imagery suggests a ritual honoring the goddess that was intended to ensure the well-being of the land, sustained by its two life veins, the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers.

In a boat stands a “priest-king,” the highest-ranking ruler in the first cities, represented with a long beard and a netted skirt revealing the rounded forms of his lower body. He faces a bull supporting a two-tiered altar crowned with reed ring bundles with streamers, symbols of Inanna. Behind him is a wattled structure, possibly standing for a temple facade. Two attendants navigate the boat from the bow and stern, which are adorned with buds. This seal, with a silver knob in the form of a recumbent calf, was buried in the sacred precinct of Inanna in Uruk. Its imagery suggests a ritual honoring the goddess that was intended to ensure the well-being of the land, sustained by its two life veins, the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with “priest-king” and altar on the back of a bull

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Uruk (modern Warka), Eanna Precinct

Late Uruk–Jemdet Nasr period, ca. 3300–2900 BC

Lapis lazuli and silver

Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Excavated 1933–34; VA 11040

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Foto: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Sidney Babcock: A ritual is taking place in a boat and we have already met its main characters in the Uruk Vase: the goddess Inanna and the ruler. The goddess is represented here symbolically, through an altar with reed ring bundles placed on top of a bull. Facing the altar is the ruler, depicted significantly larger than the other figures. His long beard and netted skirt offer clues to his identity. The structure behind him is most likely a temple of Inanna. Two attendants navigating the boat at the bow and stern complete this rare composition. Found buried in the temple precinct of Uruk, its boat imagery suggests that this ritual honoring Inanna had to do with two life lines of the region, the Euphrates and the Tigris Rivers.

This remarkable seal was carved of lapis lazuli imported from modern-day Afghanistan, and embellished with a silver knob in the form of a recumbent calf. Such knobs are among the earliest known examples of lost-wax casting, which is based on making a model in wax and covering it with clay. When heated, the clay hardens, the wax melts and runs out of the mold, and the ensuing space is filled with molten metal. Already perfected in ancient Mesopotamia, this ingenious technique was later popularized in the Greco-Roman antiquity and is still in use today.

Fragment of a vessel with frontal image of goddess

This vessel fragment shows one of the first images of an anthropomorphic goddess created in Mesopotamia. The divine nature of the figure is expressed by the horned crown with feathers (or fronds) and an animal head, as well as by the vegetal elements above her shoulders, possibly identifying her as Nisaba, Ninhursag, or Inanna. While the lower half of the goddess’s seated body is shown in profile, her head and torso face forward. She stares directly at the viewer, exuding her power and authority. Her hair and the cluster of dates in her right hand depict the figure as a goddess of fertility and abundance. The inscription mentions the vase itself, called bur-sag̃ in Sumerian and dedicated to this female deity.

Fragment of a vessel with frontal image of goddess

Mesopotamia, Sumerian

Early Dynastic IIIb period, ca. 2400 BC

Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian

Basalt

Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Acquired 1914–15; VA 07248

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Foto: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Sidney Babcock: Prior to the Early Dynastic period, gods and goddesses were represented by various symbols. The presence of the goddess Inanna, for example, was signaled with reed ring bundles or rosettes. This practice shifted around 2400 BC when deities began to be visualized as anthropomorphic figures, which is demonstrated by this vessel fragment. Likely part of a cup, the piece bears a powerful image of a vegetation or fertility goddess holding a cluster of dates and with vegetal elements above her shoulders. She is seated in profile while her upper body is depicted frontally—her gaze direct. Interestingly, the corners of her mouth are lifted into a smile. The horned crown that marks her as divine rests on top of her long, voluminous, braided hair that curls at the ends. Akkadian artists later appropriated iconographical features of this goddess, such as her mixed profile position, coiffure, and the form of the six elements above her shoulders, to portray Ishtar, the Akkadian counterpart of Inanna, and her martial characteristics.

Vessel with faces of female deities

A single divine female figure, anthropomorphic but with bovine features, is embodied in the two identical faces carved on this alabaster vessel. The wide-open eyes and full cheeks resemble those of statues of female worshippers during this period, while the delicately braided hair is reminiscent of contemporary depictions of goddesses—a sign of abundance and tamed wildness also expressed by the stylized cow horns. Each horn extends to circumscribe the rim of the vessel, linking the two faces to each other and to the object itself. This unity, together with the bright translucency of the alabaster, suggests that this vessel served as a divinized cultic object.

Vessel with faces of female deities

Mesopotamia, Sumerian

Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC

Inscription largely abraded in antiquity

Gypsum alabaster

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1973; 1973.33.1

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Sidney Babcock: Mesopotamian artists began depicting gods and goddesses in human form in the third millennium BC. Horns became the most prominent symbols that were used to distinguish deities from mortals, often added to depictions in the form of horned crowns. This vessel of translucent alabaster presents a rare and peculiar use of this symbol: horns are not part of an external crown here but protrude directly from the two identical female heads carved on each side of this object. Moreover, each horn extends to circumscribe the rim of the vessel, linking the two heads to each other and to the object itself.

This vessel would have been used to hold libations offered to deities. Ancient texts indicate that such ritual objects could be regarded as divine entities themselves. Therefore, rather than depicting two specific goddesses, this vessel was most likely a divinized cultic object. Once the offering was poured into the void in the middle, the two heads would metaphorically blend into one another, turning into a single divine female being.

Standing female figure with clasped hands

The dress and hairstyle of this female figure are similar to those of several other statues included in this section. Her eyes and eyebrows are emphasized by their large proportions and now-missing inlays. Traces of paint indicate that her hair was once a dark color. The sculptor took great care with the soft carving of her cheeks, details of her lips and toenails, tightly arranged curls of her hair, and fold of her left clasped hand. Her skirt is slightly shorter than other examples, accentuating the figure’s unshod feet.

Standing female figure with clasped hands

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Tutub (modern Khafajah), “Sin” Temple IX

Early Dynastic IIIa period

(2600–2450 BC)

Gypsum and shell

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Excavated 1933/34; A12412

Courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

Sidney Babcock: This statue of a female figure was a votive offering placed in a temple in present day Khafajah, which was once incorporated into the city-state Eshnunna. The temple may have been built in honor of Sin, the moon god. Several of these offerings portraying their dedicants were unearthed during excavations in the 1930s. Often, they are depicted with large eyes, accentuated eyebrows, and clasped hands. Set before the cult statue of a deity, these objects stood in place of the worshipers they portray, to pray in perpetuity long after the natural life of their dedicants. Here, this female figure placidly waits, standing with a careful and poised posture. Though certain decorative elements of this particular statue have not survived, the hollow areas of the once inlaid eyes and brows as well as the traces of pigment on her hair indicate that color was an integral part of these images. While they are still visually stunning today, it is fascinating to imagine how they may have looked as they were originally intended in antiquity and to ponder, for example, how paint would have affected the exquisite detail of this woman’s hairstyle.

Standing female figure

This statue once stood in the Ishtar Temple at Assur, the first Assyrian capital. The damage the figure has sustained since then reflects her history. Among other events, she witnessed the early days of Assur, the collapse of the Neo- Assyrian Empire in the seventh century BC, and the German excavations of the early twentieth century. While en route to Berlin during the First World War, this statue and other finds from Assur were confiscated by Portuguese forces and later exhibited in Lisbon, Portugal. They ultimately reached Berlin and were installed in the Pergamon Museum, where the statue survived heavy bombardments carried out by the Allied forces in the Second World War.

Standing female figure

Mesopotamia, Assur (modern Qal’at Sherqat), Ishtar Temple, level G, cella

Early Dynastic IIIb period, ca. 2400 BC

Alabaster

Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Excavated 1913; VA 08144

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Foto: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Sidney Babcock: Though this statue sustained significant damage during the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and both World Wars, it has survived with a few details intact including the woman’s mouth, rounded cheeks, and large eyes that were initially inlaid with semiprecious stones. Due to the dimensionality of this object, its material, and the artist’s skill, the extraordinary texture of this woman’s woven garment comes to life. It ignites a sensory curiosity about the feel and motion of her clothing. The careful articulation of the strands of her abundant hair also contributes to the allusion of texture. Like similar votive statues, this female figure once stood on a pedestal, but it has been broken off along with her feet. Yet her devotion to Ishtar endures through the ages as the angle of her neck and chin seemingly pull her forward, her gaze fixed on the divine.

Stone scraper and chisel

These two objects shaped like crafting tools form a pair. Together they record the first woman in history known by name, KA-GÍR-gal. She is depicted on the scraper’s obverse with her hands raised before her mouth in a reverent gesture. The inscriptions incised on both objects suggest that she may have been involved in a land sale as a coseller. Facing her stands a bearded figure holding an elongated object, possibly a land-sale peg, which would have been inserted into a building wall to proclaim the transaction. A similar male figure holding a young goat appears on the chisel. The figures on the scraper’s reverse may be preparing a feast to celebrate the recently concluded deal.

Stone scraper and chisel recording the first woman known by name

Mesopotamia, Sumerian

Jemdet Nasr–Early Dynastic period, ca. 3000–2750 BC

Proto-cuneiform inscriptions

Schist (phyllite)

The British Museum, London, Acquired From Dr. A. Blau, 1899; BM 86260 and 86261

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Sidney Babcock: KA-GÍR-gal: the first woman in history known by name! These two objects, shaped like a scraper and a chisel, bear an inscription mentioning her as a co-seller in a land sale. Even more fascinating is the fact that not only her name but also her image came down to us: she is represented on the scraper with her hands placed before her mouth in a gesture of reverence. Her relationship to the bearded figure standing before her is uncertain, but the object he is holding in his hands might have been a "land sale peg." Such pegs were inserted into the wall of a building to proclaim a transaction. The other depicted figures may be preparing a feast to celebrate the recently concluded deal.

As demonstrated by the Stele of Shara-igizi-Abzu as well, also on view here, women were actively involved in the economic life of early cities. The first urban centers of Mesopotamia depended on women's labor and such monuments testify to their role in selling privately owned land in ancient Sumer.

Stele of Shara-igizi-Abzu

This stele, bearing the earliest known signature of an artist, records one of the first transactions involving land, livestock, and houses. The two principal figures—Ushumgal, a priest of the god Shara, and his daughter Shara-igizi-Abzu—face one another on two sides. They are identified by inscriptions carved on their bodies. Shara-igizi-Abzu, who holds a vessel in her right hand, is shown taller than her father. Behind her appears a smaller female figure, and behind Ushumgal are three male figures in two registers, all of whom may have witnessed the transaction that takes place in front of a monumental building. Shara-igizi-Abzu’s prominent appearance suggests that the stele documents Ushumgal’s donation of an estate on her behalf.

Stele of Shara-igizi-Abzu

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, possibly Umma (modern Tell Jokha)

Early Dynastic I–II period, ca. 2900–2600 BC

Cuneiform inscription identifying Shara-igizi-Abzu; her father, Ushumgal; and four other represented figures, including: IGI.RU?.NUN, daughter of Mesi; Ag, chief of the assembly; Nanna, the foreman of the assembly; X.KU.EN, chief herald; Enhegal, the maker of the stele

Gypsum alabaster

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds From Various Donors, 1958; 58.29

Sidney Babcock: Enhegal, the maker of the stele, Gypsum alabaster; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 1958; 58.29

When we think of famous artists from antiquity, ancient Greek names such as Praxiteles or Phidias often come to mind. In fact, the earliest known artist who signed his art was the maker of this very stele, Enhegal. When he finished carving this work, he added his signature in cuneiform and immortalized his name.

What Enhegal carved was a visual record of a financial transaction. He placed each of the principal figures on two main sides and identified them through inscriptions: One of them is Shara-igizi-Abzu, the other is her father Ushumgal. They were most likely from the Sumerian city of Umma, where Ushumgal worked as a priest. Here, signifying her prominent position, Shara-igizi-Abzu is depicted taller than her father. The rest of the inscription suggests that she was the recipient of an estate donated by Ushumgal. The smaller figures depicted on the other faces of the stele are witnessing this transaction.

Now, look at the building before Ushumgal. In the middle of the wall, you will see a little notch. This is for a peg inserted into a building to proclaim this transaction. We have seen one of such pegs in another artwork on view here, namely in the hands of the male figure before KA-GÍR-gal.

Wall plaque with libation scenes

This wall plaque was found in the gipar, the residence of the high priestess of the moon god Nanna at Ur, which was likely occupied by Enheduanna in her day. A high priestess is represented frontally in the lower register. Wearing a long cloak and a circlet resembling Enheduanna’s headdress, she oversees a ritual in which a clean-shaven, nude man pours a libation into a date-palm vase in front of a temple. Two attendants carrying offerings stand behind her. In the upper register, another libation scene takes place inside the temple before a statue of the enthroned deity. The use of frontality to represent the high priestess, an artistic device associated with contemporary depictions of goddesses, accentuates her authority as the overseer of this libation ritual.

This wall plaque was found in the gipar, the residence of the high priestess of the moon god Nanna at Ur, which was likely occupied by Enheduanna in her day. A high priestess is represented frontally in the lower register. Wearing a long cloak and a circlet resembling Enheduanna’s headdress, she oversees a ritual in which a clean-shaven, nude man pours a libation into a date-palm vase in front of a temple. Two attendants carrying offerings stand behind her. In the upper register, another libation scene takes place inside the temple before a statue of the enthroned deity. The use of frontality to represent the high priestess, an artistic device associated with contemporary depictions of goddesses, accentuates her authority as the overseer of this libation ritual.

Wall plaque with libation scenes

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), gipar

Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC

Limestone

The British Museum, London, Excavated 1925/26; BM 118561

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Sidney Babcock: Divided into registers are two libation scenes. In the lower register, a clean-shaven, nude man pours a libation into a vase before a temple. Niches were incorporated into the façade of this architectural structure and gateposts stand on each side of it. Behind the male figure is the high priestess and she is followed by two figures holding offerings—one of them is carrying an animal for sacrifice. The upper register depicts events occurring inside the temple where a libation is poured before the cult statue of a deity who is portrayed with both hands wrapped around the neck of a vessel. Though the nude man who pours the libation is clean-shaven, he has long hair unlike his counterpart below. Attending the ritual in the temple are three priestesses dressed identically. The high priestess in the lower register is the sole figure to be represented frontally, which is significant given that this plaque was excavated from the residence of the moon god’s high priestess. Some of her facial features seem to have worn away, but they would have surely intensified this priestess’ authority and the impact of her image.

Cylinder seal of Queen Puabi

Seated in the top register of this banquet scene, Queen Puabi is first announced by the seal’s inscription, which names her specifically. Puabi’s chair is more decorative than those of the other celebrants, all of whom are men. Special attention was also given to her dress, draped over one shoulder, as well as her looped hair bun and prominent facial features. One of her two female attendants rests her hand on Puabi’s back, an easily missed detail suggesting the close relationship between an elite woman and her female entourage.

Seated in the top register of this banquet scene, Queen Puabi is first announced by the seal’s inscription, which names her specifically. Puabi’s chair is more decorative than those of the other celebrants, all of whom are men. Special attention was also given to her dress, draped over one shoulder, as well as her looped hair bun and prominent facial features. One of her two female attendants rests her hand on Puabi’s back, an easily missed detail suggesting the close relationship between an elite woman and her female entourage.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) of Queen Puabi

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), PG 800, Puabi’s Tomb Chamber, against Puabi’s upper right arm

Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC

Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian: Queen Pu-abi

Lapis lazuli

The British Museum, London, Excavated 1927/28; BM 121544

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Sidney Babcock: Queen Puabi's funeral in the city of Ur was a meticulously planned event. Her body was dressed in full regalia; her tomb was filled with objects displaying her status and wealth. All carved of exquisite lapis lazuli imported from modern-day Afghanistan, three cylinder seals were carefully attached to three garment pins that secured her cloak. This particular seal was found together with the garment pin that is also on view in this case.

Here, Puabi is shown seated in the upper register, participating in a banquet. The artist paid special attention to her representation: her dress, hair, and face are clearly defined, and her chair is more decorative than those of the other celebrants, all of whom are men. One of her two female attendants gently rests her hand on Puabi’s back, an easily missed detail suggesting the close relationship between an elite woman and her female entourage.

This seal is among the very few banquet scenes from Ur which contained inscriptions. In contrast to the practice of the time where women were described in relation to their male kin, Puabi's inscription only gives her name and title as queen, suggesting that she ruled in her own right.

Queen Puabi’s funerary ensemble

Puabi’s funerary ensemble is a feast for the eyes with its vibrant colors, precious materials, and skilled artisanship. Several wreaths formed of floral and vegetal motifs once rested on her forehead. Ribbons of thinly hammered gold would have circled her voluminous hair. At the crown of her head sat a large gold comb, featuring seven delicately curving flowers. Large lunate earrings dangled from her ears, and gold coils from her hair. These radiant accessories would have formed a halo around Puabi’s face. Below, a choker with a central rosette sat against her neck. A profusion of carnelian, lapis lazuli, and gold beads covered her chest, strung in rhythmic patterns. Finally, a belt of beads with a fringe of disks would have rested against Puabi’s hips.

Queen Puabi’s funerary ensemble

Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), PG 800, Puabi’s Tomb Chamber, on Puabi’s body

Early Dynastic IIIa period, ca. 2500 BC

Gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian, silver, and agate

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, Excavated 1927/28

Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidney Babcock: Queen Puabi's funeral in the city of Ur was a meticulously planned event. Her body was dressed in full regalia; her tomb was filled with objects displaying her status and wealth. All carved of exquisite lapis lazuli imported from modern-day Afghanistan, three cylinder seals were carefully attached to three garment pins that secured her cloak. This particular seal was found together with the garment pin that is also on view in this case.

Here, Puabi is shown seated in the upper register, participating in a banquet. The artist paid special attention to her representation: her dress, hair, and face are clearly defined, and her chair is more decorative than those of the other celebrants, all of whom are men. One of her two female attendants gently rests her hand on Puabi’s back, an easily missed detail suggesting the close relationship between an elite woman and her female entourage.

This seal is among the very few banquet scenes from Ur which contained inscriptions. In contrast to the practice of the time where women were described in relation to their male kin, Puabi's inscription only gives her name and title as queen, suggesting that she ruled in her own right.

Disk of Enheduanna

The fragmentary inscription on this disk was recovered from a copy on an Old Babylonian (ca. 1894–1595 BC) tablet, recorded hundreds of years after the disk’s dedication by Enheduanna. The scene carved on the opposite side shows an open-air sacred precinct with a multistory edifice at left. Enheduanna occupies the center, depicted slightly larger than her attendants to reflect her status. Two priests behind her carry ritual paraphernalia; the one in front of her pours a libation on an altar. Enheduanna wears a tiered, flounced garment and a headdress in the form of a circlet, both of which became canonical for her successors. Her hand gesture sanctions the ritual. Her well-sculpted visage gazes upward, from the mortal world to the numinous realm of Inanna.

Disk of Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon

Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), gipar

Akkadian period, ca. 2300 BC

Cuneiform inscription in Sumerian: En-h[e]du-ana, zirru priestess, wife of the god Nanna, daughter of Sargon, [king] of the world, in [the temple of the goddess Inan]na-ZA.ZA in [U]r, made a [soc]le (and) named it: ‘dais, table of (the god) An.’

Alabaster

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, Excavated 1926; B16665

Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidney Babcock: Excavated in Enheduanna's sacred dwelling in Ur, this alabaster disk is the only surviving artwork that records both her name and image. On one side, there are traces of a cuneiform inscription identifying Enheduanna as the wife of the god Nanna and the daughter of King Sargon. This text was copied on a tablet centuries after her lifetime, confirming the longevity of her legacy. Thanks to that copy, we know that Enheduanna dedicated this enigmatic disk to a temple to commemorate the construction of a hallowed dais.

The carving on the other side shows a ritual taking place before a stepped edifice. Enheduanna is at the center, depicted taller than the priests accompanying her. She wears a flounced garment and a headdress in the form of a circlet, both of which became characteristic features of high priestesses for centuries to come. The priest before her is pouring a libation over an altar, while Enheduanna is overseeing this ceremony and sanctioning it with her hand gesture. By doing so, she is continuing a ritual established in the cult practices of the Sumerians as represented by the frontally depicted woman on the wall plaque described in Stop 10, exhibition object number 41. Her well-sculpted visage gazes upward, from the world of the mortals to that of the divine.

Seated female figure with tablet on lap

Most likely representing a high priestess, this statuette calls forth a line from “The Exaltation of Inanna” by Enheduanna: “Me, who once sat triumphant.” The image also resonates with that of Enheduanna on her votive disk. The woman’s transfixed gaze expresses deep reflection and her hands are firmly clasped in devotion. In her lap is a small tablet. Three incisions on its surface represent the columnar division of clay tablets, an overt reference to cuneiform writing. The tablet and divisions bear witness to the dedicator’s well educated status and engagement with writing, perhaps as an author. As a votive, the statue’s offering is a written text.

Seated female figure with tablet on lap

Mesopotamia, Neo-Sumerian

Ur III period (ca. 2112–2004 BC)

Alabaster

Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Acquired 1913; VA 04854

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Foto: Olaf M. Teßmer.

Sidney Babcock: Hands firmly clasped, eyes transfixed ahead... Despite sharing these characteristics with all the other votive statues on view here, this figure stands out due to a critical but easily overlooked aspect: a small tablet is placed on her lap. Three orderly incisions divide the empty surface of this tablet into four columns, clearly signifying the figure's familiarity with the cuneiform script. This is nothing short of a declaration of authorship, monumentalized in this subtle composition carved of radiant alabaster. What is being dedicated to divinities here is writing itself, conveyed through a tablet ready to be inscribed.

But who is this figure? Iconographical features such as long, loose hair and flounced robe strongly suggest that she was a high priestess, just like Enheduanna. There are three other statues of women with tablets on their laps, all dated slightly later than Enheduanna’s time. It is intriguing to regard these profound visual manifestations of women and literacy as reflecting the longevity of the persona of Enheduanna herself.

Tablet inscribed in Sumerian with Temple Hymns

One of the hymns recorded on this tablet is on the temple of Enlil in Nippur. The supreme god Enlil was worshipped in many cities, but the Nippur temple was his principal abode. According to Sumerian mythology, Nippur was one of the primordial cities where heaven and earth met. It was also located strategically, connecting northern and southern Mesopotamia— making it an attractive political node for rulers of Mesopotamia, including Enheduanna’s father, King Sargon.

Tablet inscribed in Sumerian with Temple Hymns

Mesopotamia, Nippur (modern Nuffar)

Old Babylonian period (ca. 1894–1595 BC)

Clay

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, Excavated 1890–93; CBS 07073 + N 1193 + N 7018 + N 7028 + N 7900

Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidney Babcock: Enheduanna compiled and wrote short hymns written for sanctuaries located in cities throughout Mesopotamia. These hymns unified the religious landscape by associating the temples of the south with those in the north, perhaps in line with the broader political aspirations of Enheduanna’s father, king Sargon. One of the hymns recorded on this tablet is about the temple of the supreme god Enlil in Nippur. According to Sumerian mythology, Nippur was a primordial city where heaven and earth met. It was also located strategically—connecting northern and southern Mesopotamia—making it an attractive political node for rulers:

Nimet Habachy:

O [ ], shrine where fate is determined,

[ ], foundation, raised by a ziggurat,

[ ], residency of Enlil,

your [ ], your right and your left are Sumer and Akkad.

O House of Enlil, your interior is cool, your exterior determines fate.

your doorjamb and your beam are a high mountain,

your projecting gate-tower is a glorious mountain.

your [ ] is a princely holy area,

your base brings together heaven and earth.

Your prince, the great prince Enlil, the good lord,

the lord of the boundary of heaven, the lord who determines fate,

O shrine of Nippur, great mountain of Enlil,

he erected a house in your holy area and took a seat upon your dais.

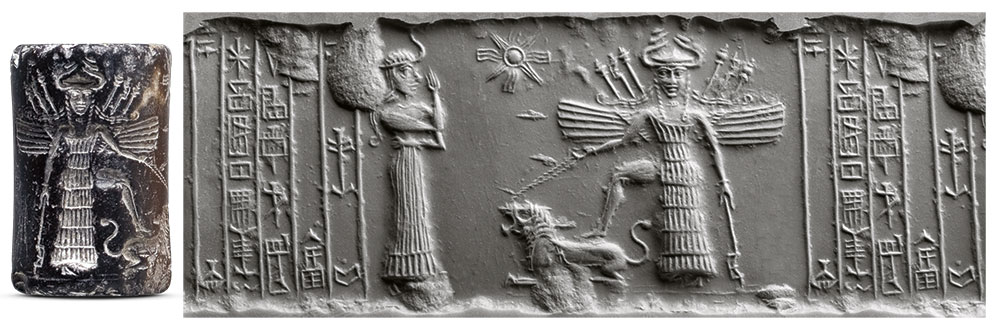

Cylinder seal with Mesopotamian deities

Once belonging to a scribe, this spectacular seal features a group of deities, some of whom are mentioned in Enheduanna’s temple hymns. In the middle, the water god Enki has streams of water and fish flowing from his shoulders. Behind him stands his attendant, the two-faced god Usmu. The figure rising between the mountains is the sun god Shamash, who holds a serrated knife as rays emanate from his shoulders. On the mountain to the left stands Ishtar, represented frontally with weapons rising from her winged body and holding a cluster of dates. The identity of the armed god behind Ishtar is uncertain. This divine gathering will culminate in a meeting with the supreme god Enlil, as shown on the next seal in this case.

Once belonging to a scribe, this spectacular seal features a group of deities, some of whom are mentioned in Enheduanna’s temple hymns. In the middle, the water god Enki has streams of water and fish flowing from his shoulders. Behind him stands his attendant, the two-faced god Usmu. The figure rising between the mountains is the sun god Shamash, who holds a serrated knife as rays emanate from his shoulders. On the mountain to the left stands Ishtar, represented frontally with weapons rising from her winged body and holding a cluster of dates. The identity of the armed god behind Ishtar is uncertain. This divine gathering will culminate in a meeting with the supreme god Enlil, as shown on the next seal in this case.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with Mesopotamian deities

Mesopotamia, Akkadian, possibly Sippar (modern Abu Habbah)

Akkadian period, ca. 2200–2154 BC

Cuneiform inscription: Adda, scribe

Greenstone

The British Museum, London, Acquired by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1891; BM 89115

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Sidney Babcock: During the Akkadian period, there was a significant development in glyptic art: the specific iconographies of gods and goddesses were established and depicted in a consistent manner, allowing the deities to be identified. Carved on greenstone, the first of these two seals shows several deities—Enki, Usmu, Shamash, Ishtar, and an armed god—gathering at dawn. In the next seal, Ishtar and Enki honor Enlil, who sits enthroned in his mountain abode, by raising their hands in a gesture of reverence. The artists who created these objects not only paid close attention to the deities and their identifying characteristics, but they also approached the natural landscape thoughtfully and illustrated it in detail. Small round mounds grouped together form mountains. The seal that once belonged to a scribe named Adda even depicts a caprid, perhaps a mountain goat, in this terrain. Adorning the landscape, trees rise from the earth, their branches sprouting delicate leaves.

Tablet inscribed with "The Exaltation of Inanna"

Tablet inscribed with "The Exaltation of Inanna"

Mesopotamia, Nippur (modern Nuffar)

Old Babylonian period, ca. 1750 BC

Clay

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, Babylonian Expedition Fund Purchase, 1888; CBS 7847

Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidney Babcock: "The Exaltation of Inanna" is a powerful statement of Enheduanna's devotion to the goddess of sexual love and warfare, with invaluable autobiographical references to the author's life as a high priestess. The extract is from the beginning of the poem, in praise of Inanna's might and anger:

Nimet Habachy:

“Queen of all cosmic powers, bright light shining from above,

Steadfast woman, arrayed in splendor, beloved of earth and sky,

Consort of Heaven, whose gem of rank is greatest of them all,

Favored for the noblest diadem, meet for highest sacral rank,

Who has taken up in hand cosmic powers sevenfold,

My lady! You are warden of the greatest cosmic powers,

You bore them off on high, you took them firm in hand,

You gathered them together, you pressed them to your breast.

You spew venom on a country, like a dragon.

Wherever you raise your voice, like a tempest, no crop is left standing.

You are a deluge, bearing that country away.

You are the sovereign of heaven and earth, you are their warrior goddess!”

Tablet inscribed with extract from "The Exaltation of Inanna"

Tablet inscribed with extract from "The Exaltation of Inanna"

Mesopotamia, Larsa (modern Tell Senkereh)

Old Babylonian period, ca. 1750 BC

Clay

Musée Du Louvre, Département Des Antiquités Orientales, Paris, Acquired Before 1930; AO 6713

© RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photography by Stéphane Maréchalle.

Sidney Babcock: After praising Inanna's unyielding strength, Enheduanna accuses a certain Lugalanne of attempting to forcefully remove her from her office. This Lugalanne is most likely the historically attested king of Ur, who participated in an unsuccessful revolt against the Akkadian king Naram-Sin, Enheduanna’s nephew. Here, she hints at Lugalanne’s harassments, which she will elaborate on in later sections:

Nimet Habachy:

“Yes, I took up my place in the sanctuary dwelling,

I was high priestess, I, Enheduanna.

Though I bore the offering basket, though I chanted the hymns,

A death offering was ready, was I no longer living?

I went towards light, it felt scorching to me,

I went towards shade, it shrouded me in swirling dust.

A slobbered hand was laid across my honeyed mouth,

What was fairest in my nature was turned to dirt.

O Moon-god Suen, is this Lugalanne my destiny?

Tell heaven to set me free of it!

Just say it to heaven! Heaven will set me free!”

Tablets inscribed with "The Exaltation of Inanna" (1 of 3)

These three tablets include the entire poem. The extract below begins with Enheduanna’s plea to Inanna, which details how Lugalanne desecrated the temple of An, the sky god, and forced Enheduanna out of her office, vividly alluding to sexual harassment for the first time in literature. In the end, Inanna accepts her plea, and Enheduanna is reinstated. Enheduanna then adds a remarkable line about her creative process, stating that she has “given birth” to this poem.

Tablets inscribed with "The Exaltation of Inanna" in three parts

Mesopotamia, possibly Larsa (modern Tell Senkereh)

Old Babylonian period, ca. 1750 BC

Clay

Yale Babylonian Collection, Purchase; YPM BC 018721/YBC 4656 (Lines 1–52), YPM BC 021234/YBC7169 (Lines 52–102), YPM BC 021231/YBC 7167 (Lines 102–53)

Courtesy of the Yale Babylonian Collection. Photographygraphy by Klaus Wagensonner.

Sidney Babcock: These three tablets include the entire poem. The extract you will hear begins with Enheduanna’s plea to Inanna, which details how Lugalanne desecrated the temple of An, the sky god, and forced Enheduanna out of her office by taking away her distinguishing headdress and by encouraging her to commit suicide. She vividly alludes to sexual harassment for the first time in world literature:

Nimet Habachy:

“I am Enheduanna, let me speak to you my prayer,

My tears flowing like some sweet intoxicant:

“O Holy Inanna, may I let you have your way?

I would have you judge the case.”

Sidney Babcock: Indictment of Lugalanne

Nimet Habachy:

“That man has defiled the rites decreed by holy heaven,

He has robbed An of his very temple!

He honors not the greatest god of all,

The abode that An himself could not exhaust its charms, its beauty infinite,

He has turned that temple into a house of ill repute,

Forcing his way in as if he were an equal, he dared approach me in his lust!”

[ . . . ]

“When Lugalanne stood paramount, he expelled me from the temple,

He made me fly out the window like a swallow, I had had my taste of life,

He made me walk a land of thorns.

He took away the noble diadem of my holy office,

He gave me a dagger: ‘This is just right for you,’ he said.”

Tablets inscribed with "The Exaltation of Inanna" (2 of 3)

Sidney Babcock: Facing the formidable threat of Lugalanne, Enheduanna intensifies her passionate plea to Inanna. In the end, the goddess accepts her prayers, and Enheduanna is restored to office:

Sidney Babcock: Listen to Enheduanna’s Appeal to Inanna

Nimet Habachy:

“O precious, precious Queen, beloved of heaven,

Your sublime will prevails, let it be for my restoration!

[ . . . ]

Show that you stand high as heaven

Show that you reach wide as the world

Show that you destroy all unruly lands

Show that you raise your voice to foreign countries

Show that you smash head after head,

Show that you feed on kill, like a lion,

Show that your eyes are furious,

Show that your stare is full of rage,

Show that your eyes gleam and glitter

Show that you are unyielding, that you persevere,

Show that you stand paramount,

For if Nanna said nothing, he meant, ‘Do as you will.’”

Sidney Babcock: Now listen to the Restoration of Enheduanna

Nimet Habachy:

“The almighty queen, who presides over the priestly congregation,

She accepted her prayer.

Inanna’s sublime will was for her restoration.

It was a sweet moment for her [Inanna], she was arrayed in her finest, she was beautiful beyond compare,

She was lovely as a moonbeam streaming down.

Nanna stepped forward to admire her.

Her divine mother, Ningal, joined him with her blessing,

The very doorway gave its greeting too.

What she commanded for her consecrated woman prevailed.

To you, who can destroy countries, whose cosmic powers are bestowed by Heaven.

To my queen arrayed in beauty, to Inanna be praise!”

Tablets inscribed with "The Exaltation of Inanna" (3 of 3)

Sidney Babcock: For the first time in the history of world literature, an author describes her own creative process in the "Exaltation of Inanna." Enheduanna states how she has "given birth" to this poem:

Nimet Habachy:

“One has heaped up the coals (in the censer), prepared the lustration.

The nuptial chamber awaits you, let your heart be appeased!

With ‘it is enough for me, it is too much for me!’ I have given birth, oh exalted lady, (to this song) for you.

That which I recited to you at (mid)night

May the singer repeat it to you at noon!”

Cylinder seal with Ishtar holding a weapon; deities engaging in combat

On the left, two gods battle each other; another god fights a bull-man. The deities are distinguished by their horned crowns. To the right, Ishtar gives a triple-headed mace with daggers to another divine figure while enthroned upon a defeated mountain god, whose head, arm, and feet protrude from the rocks. The scene evokes the hymn “Inanna and Ebih,” in which the goddess destroys the mountain range Ebih for not fearing her. Here, reinforcing her association with fertility, Ishtar’s portrayal is similar to contemporary depictions of vegetation gods, which are typically shown seated upon wheat, handing bundles of plants to other deities. Repurposing that composition, the artist replaced vegetal elements with weapons to express Ishtar’s warlike nature, as conveyed throughout Enheduanna’s hymn.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with Ishtar holding a weapon; deities engaging in combat

Mesopotamia, Akkadian

Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC)

Chlorite or steatite

Musée Du Louvre, Département Des Antiquités Orientales, Paris, Acquired 1911; AO 4709

RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photography by Mathieu Rabeau.

Sidney Babcock: The scene carved on this seal seems to illustrate Ishtar’s victory over the mountain range Ebih, written in the hymn Inanna and Ebih. In this text, the goddess declares:

Nimet Habachy:

“I have killed your heart and flattened you.”

Sidney Babcock: Describing her triumph further, she says:

Nimet Habachy:

“My anger, a harrow with giant teeth, has ripped apart the mountain. I built a place and have done additional things.

I put a throne in place and made its foundation sure.

I gave the kurgarra daggers and maces.”

Sidney Babcock: Aspects of this passage are reflected on the right where Ishtar and her throne crush a defeated mountain god, whose head, arm, and feet protrude from the rocks. Meanwhile, Ishtar bestows maces and daggers upon the figure standing before her. This is one of three seals on view that may have been inspired by the hymn, as they each show Ishtar dominating a god associated with a mountain in different ways—perhaps representing the stages of Ebih’s destruction. Previously, scholars proposed that the images relate to The Epic of Creation or portray deities leaving their enclosures. Brought together for the first time here, these seals are presented from a fresh perspective that explores the impact of Enheduanna’s written works.

Cylinder seal with goddesses Ninishkun and Ishtar

The eight-pointed Venus star, Ishtar’s astral emblem, hovers at the top of this scene. Below, the goddess herself is shown subduing a lion by pulling its reins and pressing down with her foot. She is approached by the minor deity Ninishkun, who raises her hand in reverence. Ishtar’s martial qualities are evident from the weapons seen above her shoulders, the sickle axe with a fenestrated blade that she wields, and the veins protruding from her leg. In “A Hymn to Inanna,” Enheduanna describes the goddess as “mounted on a harnessed lion cutting down those who are not afraid.” When encountering Ishtar, fear was the necessary response, and utter destruction befell those who did not react in terror. For this transgression, Ishtar violently obliterated an entire mountain range.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with goddesses Ninishkun and Ishtar

Mesopotamia, Akkadian

Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC)

Cuneiform inscription: To the deity Niniškun, Ilaknuid, [seal]-cutter, presented (this)

Limestone

The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Acquired 1947; A27903

Courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

Sidney Babcock: The inscription carved onto this cylinder seal reveals that it was dedicated to the goddess Ninishkun by Ilaknuid, a seal cutter. Not much is known about this minor deity, who is shown on the left in the impression, reverently raising her hand as she approaches the goddess Ishtar. Here Ninishkun acts as an intermediary, presenting requests to Ishtar on behalf of the seal cutter. This was a form of supplication in ancient Western Asia. Ishtar, the goddess of sexual love and war, is depicted with wings and martial attributes. Ready for battle, she wields an axe with a fenestrated blade in one hand. Several of these axes appear above her shoulders along with maces. With the other hand she restrains a lion as she presses her foot down on the animal. Her dominance is also expressed by the presence of her astral emblem: the eight-pointed Venusor Ishtar, that hovers above the scene.

Mold fragment with deified ruler and Ishtar

The goddess Ishtar in her warrior aspect sits on her lion throne atop a stepped platform. Seated across from her as if an equal is the Akkadian king Naram-Sin, Enheduanna’s nephew and Sargon’s grandson, whose deified status is also indicated by his horned crown. He clasps a ring with four attached ropes; Ishtar grasps his wrist with one hand and with the other guides the ropes behind her back. The ropes are attached to the nose rings of captured mountain gods bearing offerings, perhaps precious minerals, and shackled rulers standing on buildings that represent their cities. They all look up to Naram-Sin, who looks directly at Ishtar. Ishtar’s commanding frontal gaze and the angularity of her assertive gesture indicate that it is through her power and with her blessing that Naram-Sin is king.

Mold fragment with deified ruler and Ishtar

Mesopotamia, Akkadian

Akkadian period, ca. 2220–2184 BC

Limestone

Anonymous loan

Sidney Babcock: Clearly the work of a most accomplished seal carver, the fragmentary mold demonstrates another aspect of the complex iconography developed by the Akkadian artists—for expressing not a mythological setting for a god, but a real setting for an actual living god—the deified king, Narim-Sin.

He is depicted seated as an equal with Ishtar upon a stepped structure most likely the holy dais of Agade, the capitol city of the empire on which according to a later text Narim-Sin rose daily like the sun god. Narim-Sin and Ishtar are deciding matters together and are ruling over the conquered world. How different this view of the order of things is from the scene on the Uruk vase discussed in stop 2 object no 9, where the ruler approaches the goddess with offerings reflecting the careful nurture of the land. Instead, here, two subjugated mountain gods present bowls containing tribute to Ishtar and Narim-Sin. Representing precious raw materials and are a visual manifestation of the idea and importance of resource extraction that is the perogative of the conqueror. The scene visually indicates and emphasizes that it is through the goddess Ishtar that Narim-Sin has not only conquered one mountainous area but that he also rules that region by the goddesses intervention. The lost scenes surrounding the central scene of the mold must have shown other conquered and controlled parts of the empire. As a whole, the object was essentially a world map of Narim-Sin’s empire with perhaps the capitol, Agade at its center.

Cylinder seal with mother and child attended by women

This carnelian seal features an exceptional depiction of a mother and child. A similar motif of a goddess with a child in her lap is seen in other Akkadian cylinder seals, but this woman is not divine: her coiffure and fringed dress match those of the three mortal women in the scene. These women, attendants, look toward the seated pair and present offerings of fronds and vessels. The mother looks lovingly at her child, emphasizing her role as caretaker; the little one gazes back at her adoringly.

Cylinder seal (and modern impression) with mother and child attended by women

Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar),

PG 871

Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC)

Carnelian and gold

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, Excavated 1928; B16924

Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidney Babcock: Excavated from the ancient city of Ur, this object is a rare example of a seal that has survived with its original gold caps mostly intact. In addition to the gold material, the stone itself is also significant. The scene was carved on carnelian, which may have been sourced from the Indian subcontinent. The stone is evidence that the Mesopotamians successfully established and maintained trade relations with distant regions. As for the scene, it is one of tenderness and nurturing. A mortal woman is depicted seated with a child in her lap while female attendants offer various gifts including a palm frond, a cup, and a large vessel. The mother holds her child with fondness, and they affectionately gaze at one another. Immortalized in stone, such scenes emphasize the veneration and importance of motherhood and the role of caretakers—both mortal and divine—in Akkadian society.

Head of a high priestess (?) with inlaid eyes

Found alongside other sculpture fragments in the sacred precinct at Ur, this female head retains its deeply cut, piercing eyes, outlined with bitumen and inlaid with light-colored shell and blue lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan. Her striking gaze is complemented by her symmetrical, arching eyebrows, which are connected to her partially preserved nose. A few of the finely rendered strands of her choker are still visible. Her wavy hair is held in place by a circlet reminiscent of Enheduanna’s headdress. There is no inscription to confirm the figure’s identity, but the stylistic and iconographic features suggest that the statue represents a high priestess.

Head of a high priestess (?) with inlaid eyes

Mesopotamia, Akkadian, Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar), area EH, south of gipar

Akkadian period (ca. 2334–2154 BC)

Alabaster, shell, lapis lazuli, and bitumen

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, USA, Excavated 1926; B16228

Courtesy of the Penn Museum

Sidney Babcock: It is extremely rare that an ancient statue retains its original inlays. Such remarkable cases allow us to have a better understanding of the visual impact of artworks on ancient viewers. This statue confirms what an awe-inspiring sight it would have been: Its deeply cut, piercing eyes were outlined with bitumen and inlaid with light-colored shell and blue lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan. Her striking gaze is complemented by her symmetrical, arching eyebrows, which are connected to her partially preserved nose. A few of the finely rendered strands of her choker are still visible.

This head was found alongside other sculpture fragments in the sacred precinct at Ur, but none of those fragments belonged to the body to which it was once attached. Without an accompanying inscription, it is impossible to identify her with certainty but her long, flowing hair held in place by a circlet suggests that she was a high priestess. We have seen a similarly shaped headdress on Enheduanna herself.