Ashley Bryan & Langston Hughes: Sail Away

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022) was an artist, author, and teacher who wrote and illustrated over forty children’s books. From spirituals to African folktales to the work of Black poets and novelists, these books focused on Black life, history, and creativity. Through them, Bryan shared the poetry, stories, and songs he loved with young audiences.

One of the writers most important to him was the poet Langston Hughes (1901–1967). In 2015 Bryan paid tribute to Hughes with Sail Away, a book pairing original collages with Hughes’s poems about the sea. This exhibition explores the creation of Sail Away, as well as Hughes’s and Bryan’s long and fruitful engagement with the themes of seas, rivers, oceans, and other aquatic subjects. From Hughes’s memoir The Big Sea to Bryan’s vibrant depictions of boats, sailors, and fish— plus the occasional mermaid—in his many children’s books, both men found perpetual inspiration in the world of the water.

Ashley Bryan and Langston Hughes: Sail Away is made possible by the Lucy Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund, Agnes Gund, and the Caroline Morgan Macomber Fund, with support from Mo and Anjali Assomull, The Lunder Foundation – Peter and Paula Lunder Family, Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing, and Dian Woodner.

Bryan’s First Book

Ashley Bryan at work on Sail Away, 2014.

Photo: Rose Russo, Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Sandy Campbell: Ashley made books throughout his life. In this clip, you’ll hear him talking about the first book he ever made, and how his first readers–his teacher and his parents -- reacted to it.

Ashley Bryan: I grew up in New York City, born in Harlem, raised in the Bronx, and in elementary school, kindergarten, we made our first books. As we learned the alphabet, we did pictures for each letter. And, we reached letter Z, the teacher gave us construction paper. We sewed the pages together, she said you've just published an alphabet book–you are the author, the illustrator, the binder. Take it home, you are the distributor as well. Now when I brought that book home I got so much praise for it I could hardly wait to go back to kindergarten and publish more books. When we learned the numbers we did pictures for each number, sewed it together, a numbers book, and learned to spell words, boy, cat, hat, box, block, sewed it together with a word book. And so I continued making books from kindergarten on, I've never stopped. All through the years I've made books as gifts, as presents for family and friends, and I continued that into college, taking a course in book illustration as well. But it had always been a part of my life as an artist, drawing and painting and making little books as gifts.

An Artist at War

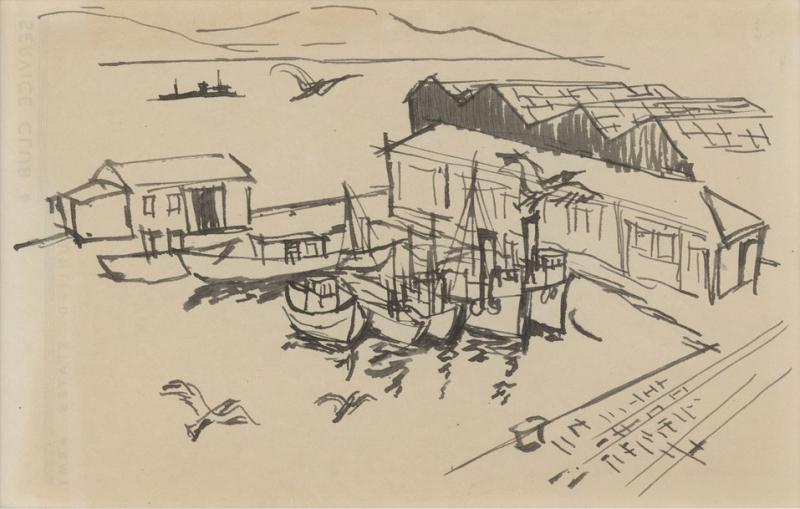

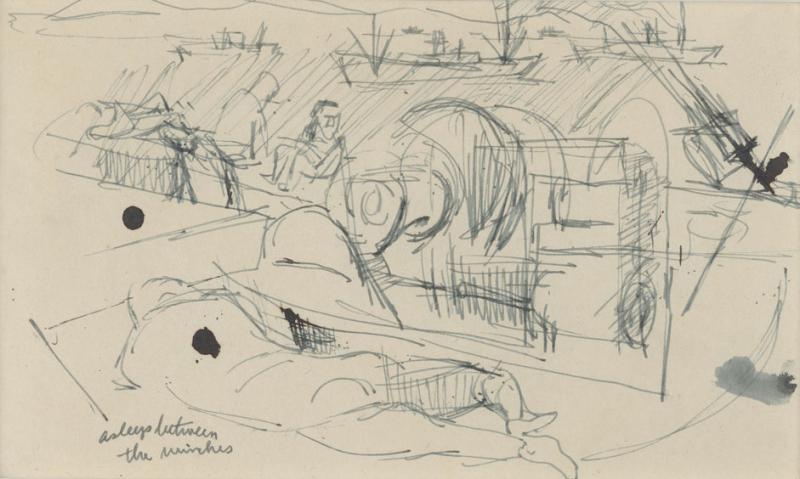

While serving as a stevedore in the segregated US Army during World War II, Bryan drew constantly. “It was,” he wrote in his 2019 memoir Infinite Hope, “my means of escape—escape into the potential beauty of a drawing, my way of staying sane, staying hopeful.” These three sketches from the period portray his everyday surroundings: ships, ports, the ocean, and the men he served with.

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Three sketches, 1943–46

Pen and ink

University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Ashley Bryan Papers

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

Sandy Campbell: When he was midway through art school, Ashley was drafted into the U.S. Army. In this interview, you can hear him talking about what it was like to serve in the segregated Army and how he continued to make art despite the challenges.

Ashley Bryan: At the time I was taking it, I was interrupted in the third year by the second World War and drafted into a segregated army in the second World War.

Sandy Phippen: What was it like, Ashley, among the black guys, American black guys, to be segregated from the rest of the Army?

Ashley Bryan: Well you immediately knew that it was very hard to maintain that spirit of what you were fighting for because you're always being used badly, you were not given the privileges of other soldiers, the white soldiers. Although we were in the invasion group and were to be retired after a month to a rest area, that never happened with the black soldiers. We continued to work in that area until the beach closed down, you see. And so, you always had that and generally, you had white officers who were not sympathetic to black people, you know, and so you always had that to contend with while you maintain your, yourself, you know, and so I was always drawing and that was a way I kept myself together and they were always telling me to stop drawing but I said, I'll never stop drawing. I had my drawing materials all in my backpack, in the gas mask, and whenever there was not a time to work, I would have out my sketch pad and I would be drawing. The fellows who had been drafted into the army or in the army said after they saw this, they said, Ashley, how did you, where did you get the time to do drawing and painting in the army? And I looked at them quite innocently and said, wasn't I supposed to keep growing as an artist? They said, Ashley, you were a GI, that meant government issue. You had no rights. But I was only fighting for what I thought were my rights. I didn't know I had none.

What Is A Jumbie?

Susan Cooper (b. 1935)

Jethro and the Jumbie

Illustrations by Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

New York: Atheneum, 1979

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased On The Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2022; PML 198770

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

Sandy Campbell: Do you know what a jumbie is? Listen as Tracey Baptiste, author of the young adult series The Jumbies, describes what she learned about these figures from Caribbean mythology when she was growing up.

Tracey Baptiste: Jumbies are not good. They're not good creatures, for the most part. Or at least this is how it was explained to me or told to me, the stories that were told to me. Jumbies are creatures who will eat you, given half the chance to eat you and so growing up, you had to know all the different ways that you could protect yourself from a jumbie so that you wouldn't get dragged off. Of course, we know what that's about – as adults, you tell these stories to children so that they stay where they're supposed to stay, you know, that's really the whole purpose behind them. But of course, as a little kid, you're thinking, your eyes are giant, you know, you're looking around, you're like, ready with all of your, you know, various accoutrements to make sure that, you know, no jumbie gets you tonight, you know? And I was fairly certain that there were people in my life who I really thought were jumbies. Ms. Evelyn, who lived next door to my grandmother. I was sure she was a soucouyant. I mean, and I still, you know, I'm fairly certain that she was, actually. So there's all of these different kinds of creatures, and so jumbies are sort of a catch-all name for a bunch of different creatures: there’s soucouyant, lagahoo, douen, La Diabless, there’s Papa Bois, there's Mama D’Leau, and those are just the ones that we talk about mostly in Trinidad and Tobago. Now throughout the Caribbean and South America, there are other types of jumbies, they may not be called jumbies, they might be called duppies. They might be called other things, but they're all part of the same type of story. And they are all fairly menacing, some to less degrees than others. Some are helpful. I actually recently found out that some of the ones that they talk about in Haiti are really quite benevolent. That's not my experience. As far as I know, they're just gonna eat you.

Oral Traditions

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Turtle Knows Your Name

New York: Atheneum, 1989

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe Jr. Acquisitions Fund, 2021; PML 198720

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

Sandy Campbell: African folktales were an important source of inspiration for Ashley. But he faced challenges when trying to write books based on these folktales. In this clip, Ashley discusses how he adapted oral traditions to the printed page.

Ashley. Bryan: I go to the Schomburg Library, I copy out these documents of stories when there are stories that interest me and then I become the storyteller. Now what can I do with stories that were in the oral tradition and it’s gonna be in a book? How can I bring something of the feeling of the oral tradition into my writing? Ah, through poetry. I use the devices of poetry in my prose. In reading any of my stories, you're gonna hear the rhyme, the rhythm, the syncopation, you'll find onomatopoeia, the playing with sounds, all of the devices of poetry work closely in my prose. What often a prose writer will avoid because they would want you to read more fluently, more directly, I am seizing upon, and using in the way I write my stories. I would like my reader to feel by reading the story, even silently, that he or she can hear the storyteller, you see. And so by using those devices of poetry, I open that up quite directly.

Two Poems by Nikki Giovanni

For the cover of a collection of poems by his friend Nikki Giovanni, the prominent writer, educator, and civil rights activist, Bryan painted a musician waist-deep in water, surrounded by a golden aura. He used a similar composition in the collage he created to illustrate Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in Sail Away.

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Cover for The Sun Is So Quiet, 1995

Tempera and gouache

University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Ashley Bryan Papers

Copyright(c) 2017 by Nikki Giovanni. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission. All Rights Reserved

Sandy Campbell: The poet Nikki Giovanni and Ashley were friends for many years, and they worked on numerous projects together. In this recording, you’ll hear two poems by Giovanni, one that she wrote in honor of Ashley’s 90th birthday and a second poem for Langston Hughes, whose work both she and Ashley admired greatly.

Nikki Giovanni: Ashley Bryan, on the joyous celebration of his 90th birthday. One head, not too big. Two eyes, though one will do, but at least one. Two ears, not necessarily other than for balance. Broad shoulders, we are after all describing a man. Two hands, two arms, surely only half needed, but with strong teeth, not even that. Two legs, two feet, mostly for locomotion. But again, consider the options. One mostly travels in one's head. And of course, a heart, a very big heart with two pockets, one to pump and a side pocket to deposit and dispense love. Don't forget a smile and a hearty laugh wrapped up in gentleness. Ashley.

A poem, for Langston Hughes. Diamonds are mined. Oil is discovered. Gold is found but thoughts are uncovered. Wool is sheared. Silk is spun, weaving is hard but words are fun. Highways span. Bridges connect. Country roads ramble, but I suspect if I took a rainbow ride I could be there by your side. Metaphor has its point of view, allusions and illusions too. Meter, verse, classical, free, poems are what you do to me. Let's look at this one more time, since I put this rap to rhyme. When I take my rainbow ride, you'll be right there at my side. Hey bop, hey bop, hey, ri ri bop.

Words Like Freedom

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

F (for freedom), 1996

Tempera and gouache

University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Ashley Bryan Papers

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

Sandy Campbell: Ashley chose Langston Hughes’s poem “Words Like Freedom” to represent the letter “F” in his ABC of African-American Poetry, and he painted this portrait of the young Hughes to accompany it. Just a few months before he died, Hughes gave a talk about his life and work at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the course of which he recited this poem.

Langston Hughes: There are words like freedom, sweet and wonderful to say. On my heartstrings freedom sings, all day, every day. There are words like liberty that almost make me cry. If you had known what I knew, you would know why.

Roll, Jordan, Roll

“Roll Jordan roll,

Roll Jordan roll,

I want to go to Heaven when I die

To hear old Jordan roll.”

—Black American spiritual,

nineteenth century

Sandy Campbell: Ashley illustrated several books of spirituals, the religious folksongs created by African-Americans during and after slavery. In this recording, the legendary gospel singer Mahalia Jackson sings “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” the spiritual Ashley chose to represent the letter “R.”

My America

Bryan painted this large watercolor as part of a collaboration with the prolific author, illustrator, and artist Dr. Jan Spivey Gilchrist (born 1949), winner of the American Library Association’s Coretta Scott King Award and many other honors. Gilchrist and Bryan both created illustrations to accompany Gilchrist’s poem “My America,” which celebrates the United States’ natural wonders, its landscapes, and its people. Bryan portrayed the country’s “mighty waters” rushing and roaring across the page.

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Mighty waters, 2006

Watercolor

University Of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center For Special Collections, Ashley Bryan Papers

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

© Jan Spivey Gilchrist

Sandy Campbell: My America, published in 2007, was an unusual project: the author and artist Jan Spivey Gilchrist wrote a poem and then both she and Ashley created illustrations for each line of the text. In this clip, Ashley, Jan, and her editor discuss the process of making the book.

[editor]: Jan had become very friendly with Ashley Bryan, who is another super talent in the children's book world.

Ashley Bryan: She got the idea of doing the book we do together, but neither one of us would see what we were doing. She wrote the poem “My America.”

Jan Spivey Gilchrist: This is actually a poem I wrote, based on my son who was a student ambassador. And I called up my editor and said, I would like for Ashley and I to both illustrate this book.

[Editor]: The cool idea she had, Ashley, in addition to being a wonderful writer, is also a super talented artist. And the idea was that both Jan and Ashley would contribute their art for this book.

Ashley Bryan: And we decided we would not see what each one was doing.

Jan Spivey Gilchrist: He was working on this book in Africa. And I was working on it here. We never saw our art, because we illustrated the same words, which had never been done before.

Ashley Bryan: That's Jan. Fantastic, terrific, great. All day long. Hoorah! That's her.

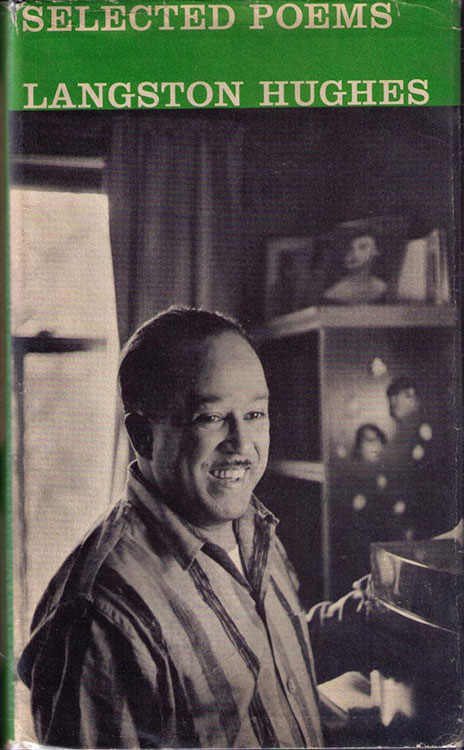

Call and Response

This is Bryan’s well-worn copy of the Selected Poems of Langston Hughes. Bryan often began events, such as talks and readings, by reciting Hughes’s poem “My People” (first published as “Poem” in 1923) and encouraging his audiences to repeat it to him in a call-and- response format.

Langston Hughes (1901–1967)

Selected Poems of Langston Hughes

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1959

Courtesy the Ashley Bryan Center

Sandy Campbell: Ashley’s recitations of Hughes’s poem “My People,” like this one, were a way to both make sure audiences were fully engaged – with their bodies as well their minds – and to help make Hughes’s poems part of people’s memories. Ashley memorized many poems, a skill he learned in elementary school, and the library in his head was an essential source that he could draw on throughout his life.

Ashley Bryan: And I begin with a poem by a wonderful black American poet and I ask everyone to say it because in this poem, he tells you, that you love who you are, and that you love your people. So I teach everyone this poem, everyone, “My People” by Langston Hughes: The night is beautiful. So the faces of my people. The stars are beautiful. So the eyes of my people. Beautiful also is the sun. Beautiful also are the souls of my people.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

Hughes wrote “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” at the age of nineteen and it was one of his earliest published works, appearing in The Crisis in June 1921. It has become a foundational poem—memorized, recited, studied, sung, illustrated, and read over and over again. Translated into many languages, it is part of the lives of people worldwide.

Hughes wrote “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” at the age of nineteen and it was one of his earliest published works, appearing in The Crisis in June 1921. It has become a foundational poem—memorized, recited, studied, sung, illustrated, and read over and over again. Translated into many languages, it is part of the lives of people worldwide.

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

The Negro Speaks of Rivers (from Sail Away), 2015

Collage of cut colored papers with graphite and printed text mounted on a tracing paper overlay

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Ashley Bryan Center; 2021.25:17

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission. All Rights Reserved.

Sandy Campbell: The story of how Hughes came to write “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” which he tells in this recording, is disarmingly simple: a young man on a train, traveling between countries, and thinking about the rivers he crosses. From this experience came one of the most important poems he would ever write.

Langston Hughes: Well, no sooner had I gotten out of high school than I went to live in Mexico with my father. My father and mother were divorced when I was quite small and he sent for me to come to Mexico, promising to send me to college. I stayed a year in Mexico, and I wrote two or three very short poems about Mexico. But the most famous of my poems, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” was written on a train going to Mexico. We were crossing the Mississippi River, just outside of St. Louis, and I looked out the window of this train and I saw this great muddy river flowing down toward the heart of the south and I began to think about what this river had meant to the negro people in the past. I remembered, my grandmother told me that, in slavery time, to be sold down the river was just about the worst thing that could happen to a slave, sold into the rice swamps of Louisiana, the heat of the Delta. And then I'd read of course about Abraham Lincoln going down the Mississippi River and how Lincoln had seen slavery at its worst when he was a young man, seen the slave markets in New Orleans. And of course, we know that many years later, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. So all of this came to my mind, and I took out an envelope, my father's letter really, out of my pocket. And on the back of his envelope I wrote this poem. Well now, most of my poems are written that way. They're what you might call spontaneous or improvisational poems, I guess. I'm not the kind of poet who studies and ponders and, and works in, in strict forms. And I'm not against writing in the sonnet form or the rondeau, or whatever forms you may be able to master – it just hasn’t happened to be my way of writing. This is a free verse poem again, as you will notice. I've known rivers. I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young. I built my hut near the Congo and allowed me to sleep. I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it. I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans. And I've seen this muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset. I've known rivers, ancient, dusky rivers. My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

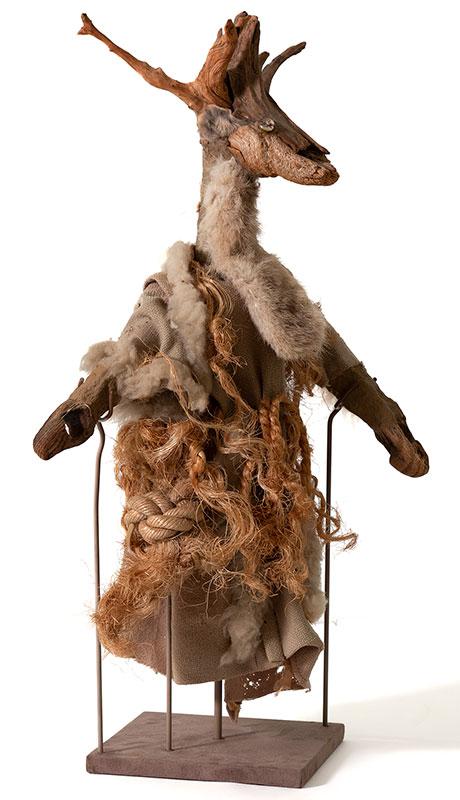

Bryan’s Puppets

For Bryan, the sea outside his door on Little Cranberry Island provided not only inspiration but also raw materials. He built many puppets out of odds and ends he found on the beach. Bryan named his puppets, drawing from The Book of African Names (Washington, DC: Drum and Spear Press, 1970), and wrote a poem for each.

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022), Osaze (puppet), 1956 and Nkosi (puppet), 1982

Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

From I Know A Man, directed by Richard Kane, 2016

Sandy Campbell: Ashley’s puppets are some of his most beloved creations. In this clip from the documentary “I Know A Man”, he describes how he makes them – or how they make themselves!

Ashley Bryan: You see, if you have two together, you'd see just the way they would look by their character. That would be all an audience would need, you know?

David Regan: It has a language of sound to go along with these gestures.

Ashley Bryan: I've been walking the shore and picking up driftwood, the bones, the seaglass, and I'm recreating from these images. It wasn't until people began asking where in Africa did I find these puppets, that I realized that that was the source that was directing and guiding me.

It's wonderful, what cast-off materials suggest, you know, and through the ages, people have worked with what's considered, um, not important. If I take a puppet, like these are just the mussel shells that get washed in, you see, the mussel shells, but it suggests a mask, a face. So if I take this and put it in my hand, and get it in there, so you see now, you see? And this is an old sweater turned over. Now it doesn't matter which one I may use, but they all work so that they come alive when they are taken off the stand. And you see how they will then work. It could be bones like these, people know these are stew bones, okay? Stew bones from different meats of your cooking. So when they get washed ashore and clean and whitened and you pick them up, well, it becomes a possibility of a puppet. When I was doing a play, I would say, this is a prince, this is a wise man, this is a fisherman, this is a carpenter. When you close a puppet in on a stage, they're absolutely believable, no matter what they look like. A little imagination, they come alive. So, everything I see becomes possible and it doesn't matter what it is. It's the silence of gesture. It's just a finger back and forth. But it tells everything in such a detailed way that you're often overwhelmed by the experience, you know, that that's why at the end of a puppet performance, if the performer then stands up in the stage area, you're always shocked because you've created a world which has a dimension of this, and not the person who stands up with it. You see? That's the magic of the whole experience, you see.

Off to Sea

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Water-Front Streets (from Sail Away), 2015

Collage of cut colored papers with graphite and printed text mounted on a tracing paper overlay

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Ashley Bryan Center; 2021.25:5

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. (p) 1955. Used by permission.

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission. All Rights Reserved

Sandy Campbell: In this recording, Langston Hughes describes going to sea as a young man and recites two of the poems that came out of that experience, “Water Front Streets” and “Long Trip.”

Langston Hughes: Once one of my dreams was to cross the Atlantic and see the world on the other side. So as a young man, I went down to the waterfront in New York and I began to try to get work as a seaman on the boats. The streets facing the piers were wide, busy, old dirty streets. Although it was spring, there were no trees or flowers, only warehouses and dark fronts and cobblestones and trucks. It was then that I wrote this poem called “Water Front Streets.” The spring is not so beautiful there. But dream ships sail away to where the spring is wondrous rare and life is gay. The spring is not so beautiful there, but lads put out to sea, who carry beauties in their hearts and dreams, like me.

Certainly one of my dreams then was to work my way across the ocean. That dream came true. I found a job on a freighter going to Africa. It took almost three weeks to cross the Atlantic from New York to Dakar in Senegal. One of my first poems about the ocean was this one called, “Long Trip.” The sea is a wilderness of waves, a desert of water. We dip and dive, rise and roll, hide and are hidden on the sea. Day, night, night, day. The sea is a desert of waves, a wilderness of water.

Seascapes and Sailors

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Seascape (from Sail Away), 2015

Collage of cut colored and painted papers with graphite and printed text mounted on a tracing paper overlay

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Ashley Bryan Center; 2021.25:6

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. (p) 1955. Used by permission.

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

Sandy Campbell: In this clip, Hughes interweaves two of his poems, “Seascape” and “Sailor,” with stories from his seafaring days.

Langston Hughes: Later, I made a trip as a seaman to Europe. As we neared the English Channel one day, off the coast of Ireland, as our ship passed by, we saw a line of fishing ships etched against the sky. Off the coast of England, as we rode the foam, we saw an Indian merchant man coming home. From foreign ports sailors often bring home souvenirs. From Africa, I brought back a monkey. Some of the sailors brought back parrots or slippers made of leopard skin, or little statuettes of brass or wood. Some sailors collect souvenirs on their own bodies in the form of tattoos, drawings made directly on their skins by tattooing artists in different ports. I once knew such a sailor. He sat up on the rolling deck, half a world away from home and smoked a Capstan cigarette and watched the blue waves tipped with foam. He had a mermaid on his arm, an anchor on his breast, and tattooed on his back he had a blue bird in a nest.

Sounds of the Deep

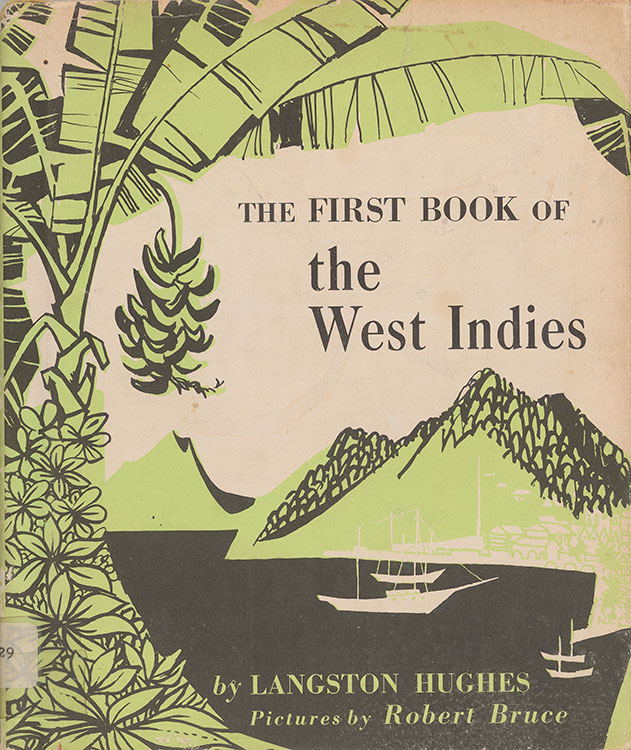

Langston Hughes (1901–1967)

The First Book of the West Indies

Illustrations by Robert Bruce (1911–1980)

New York: Franklin Watts, 1956

The Morgan Library & Museum, the Carter Burden Collection of American Literature; PML 181703

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. (p) 1955. Used by permission.

Sandy Campbell: In 1955, Hughes recorded an album for children based on his book The First Book of Rhythms. He was deeply interested in and curious about different sounds. In this clip, he has gathered sounds of the sea, from the sound of the Pacific off the coast of California to sounds of underwater creatures recorded at a depth of two thousand fathoms.

Langston Hughes: This is the sound of the Pacific off the California coast.

And here are the noises that some fish make below the surface of the sea. This is a toad fish.

Here are croakers.

And these are spot fish in a tank.

And these are the unknown sounds one hears 200 miles out in the Pacific and 2000 fathoms down in the depths of the sea.

It is only with the aid of special sound recording instruments that we can hear the sounds from the depths of the sea. But all of us who live near the sea can listen to the majestic roar of the waves on its surface.

And we can think how each grain of sand on the beach and the rhythms of each shell in the sea are molded and shaped by the waves and the tides.

Trip: San Francisco

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Trip: San Francisco (from Sail Away), 2015

Collage of cut colored papers with graphite and printed text mounted on a tracing paper overlay

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Ashley Bryan Center; 2021.25:15

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. (p) 1990. Used by permission.

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission.

Sandy Campbell: Hughes’s friend and collaborator Arna Bontemps was also an accomplished poet. Here he reads Hughes’s poem “Trip: San Francisco,” which was first published in a collection that Bontemps edited, Golden Slippers: An Anthology of Negro Poetry for Young Readers.

Arna Bontemps: “San Francisco” by Langston Hughes. I went to San Francisco, I saw the bridges high, spun across the water like cobwebs in the sky. In the morning, the city spreads its wings making a song and stone that sings. In the evening, the city goes to bed, hanging lights above its head.

Laydy Jams plays "Fulfillment"

Ashley Bryan (1923–2022)

Fulfillment (from Sail Away), 2015

Collage of cut colored and painted papers with graphite and printed text mounted on a tracing paper overlay

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of the Ashley Bryan Center; 2021.25:10

© 2022 The Ashley Bryan Center. Used with Permission. All Rights Reserved

Photography by Dessmin Sidhu

"Fulfillment" by Langston Hughes, by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

Musical composition © Sejal Lal

Sandy Campbell: Hughes’s poems have often been set to music – a form of tribute he particularly enjoyed, since he drew on the rhythms of the blues and jazz in writing his poetry. The Canadian group Laydy Jams, consisting of Sejal Lal and Missy D, emphasized the sunny, dreamy aspects of the poem in their setting.

“Fulfillment” by Langston Hughes

The earth-meaning

Like the sky-meaning

Was fulfilled.

We got up

And went to the river,

Touched silver water,

Laughed and bathed

In the sunshine.

Day

Became a bright ball of light

For us to play with,

Sunset

A yellow curtain,

Night,

A velvet screen.