The Exterior

J. Pierpont Morgan commissioned the Library during an age of conspicuous opulence among his affluent peers. The new building cost him just over $1,011,000 (about $32 million today)— a figure that does not include his purchases of two houses that were demolished to create the large lot. This photograph depicts the Library (center) and the Morgans’ Manhattan home at the corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue (far left).

Though the Library is stylistically distinct from the structures around it, Morgan insisted it be of an appropriate scale for the relatively residential neighborhood of Murray Hill. From the sidewalk, passersby could (and still can) look up to the light, spare, elegant facade, a testament to the skill of the many designers, artists, stone setters, carvers, and builders who brought the bookman’s paradise into being.

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, before 1924. Museum of the City of New York, X2010.18.286.

Beatrix Farrand, Landscape Gardener

In 1912 Morgan engaged Beatrix Jones (later Farrand), a friend of McKim’s, to landscape the grounds of his Manhattan property. In this letter, she outlined her terms to Belle da Costa Greene, Morgan’s librarian. Morgan died in March 1913 and never saw his garden “looking nicely,” as Jones had hoped he would.

Greene and Jones were the only two women who held prominent positions during the early years of the bookman’s paradise. Both went on to become national leaders in their respective fields.

Beatrix Jones (later Farrand, 1872–1959)

Letter to Belle da Costa Greene, New York, 9 October 1912

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1310

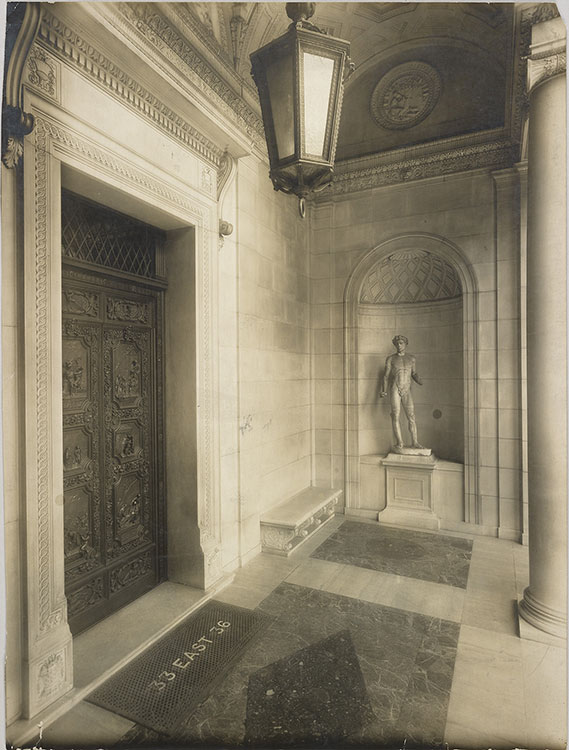

The Loggia

During Morgan’s day, visitors to his Library entered through a bronze gate along 36th Street and ascended a short flight of steps to the loggia, pictured here. As they approached the massive doors, they stepped across slabs of rose and green marble, the only touches of color against the pink-white blocks of the building’s exterior. Looking up, they would have seen a massive bronze lantern hanging from a vaulted ceiling adorned with marble carvings of notable printers’ marks (emblems).

Morgan purchased the antique statues in the lateral niches through a dealer in Rome in 1909; they were not part of McKim’s design

.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

Portico of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1590

Morgan's Gates of Paradise

Though the doors to Morgan’s Library evoke Italian Renaissance precedents (such as Lorenzo Ghiberti’s doors for the Florence Baptistery), they were a modern creation. Their origins and attribution are murky, obscured by a network of dealers.

The doors (walnut with mahogany moldings) are nine-and-a-half feet tall and adorned with cast-bronze panels that depict scenes in the life of Christ. Barely detectable at right (set into the second perimeter rosette from the bottom) is a doorbell. Guests would have pressed the button to be admitted into the ornate Rotunda.

Pach Brothers, New York

Doors of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1906–30

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1792

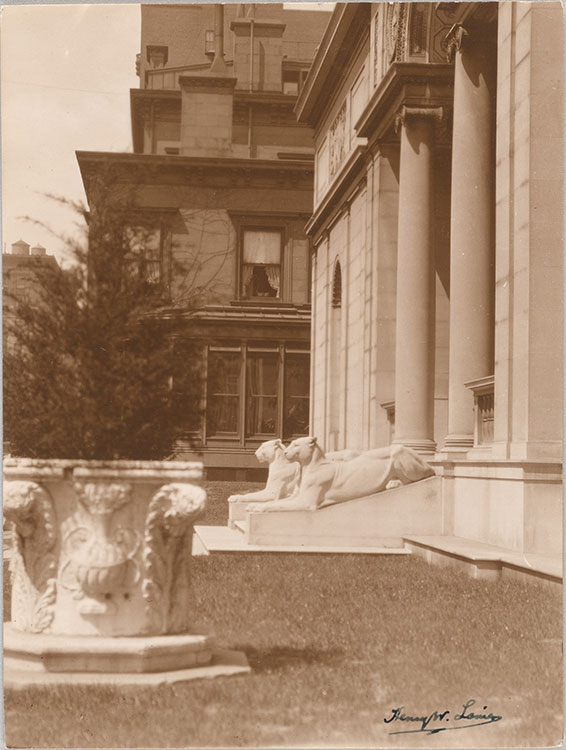

Potter's Lionesses

In 1903 Edward Clark Potter was awarded a commission of $10,000 to produce the female sentinel lions for the inclined pedestals alongside the Library’s front steps. He sketched live models at the new lion house at the Bronx Zoo and sculpted a lioness in clay in his studio in Greenwich, Connecticut. He then created plaster models for the stonecutter, who in turn worked from large blocks of Tennessee marble. (Potter likely engaged John Grignola, an Italian immigrant and accomplished carver, to execute the work.)

Potter went on to sculpt the celebrated male lions that were installed in 1911 outside the New York Public Library at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street.

Henry Wysham Lanier (1873–1958)

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1906

Gelatin silver prints

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1793, 1794, 1796, and 1798

A Luxurious Playground

After the Library was completed in 1906, several generations of Morgan children enjoyed playing on and around (and in some instances even inside) the exterior sculptures and artifacts. Here, one of Edward Clark Potter’s marble lionesses gamely sports a hat adorned with flowers. The darker building just beyond the Library was the home of J. Pierpont and Fanny Morgan, located at the corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue. The house would be demolished in the 1920s and replaced with the Annex.

Page from a Morgan family photograph album, likely depicting Mabel and Eleanor Satterlee and others, ca. 1910–24

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3281

A Spectacular Entrance

This drawing reflects the final design for the central portion of the Library’s façade, down to the details of the bronze relief panels affixed to the grand front doors. The lionesses flanking the steps would be sculpted by Edward Clark Potter.

In early designs, the dedicatory panel on the cornice, borne by a pair of winged figures, resembled an open book, but the architects revised the shape to a simple rectangle. Several early renderings show placeholder text on both the dedicatory panel and the plaque over the doors, but in the end those areas remained unlettered.

McKim, Mead & White (drafter unknown)

Detail of Loggia, Library for J. P. Morgan Esq. N.Y.C., ca. 1904

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

French Admires Potter's Feline "Beast"

McKim’s friend Daniel Chester French, one of the most prominent American sculptors of the day, recommended that the architect engage Edward Clark Potter to produce the marble lionesses that grace the Library’s entrance. In spring 1904 French visited Potter in his Connecticut studio and wrote to reassure the anxious McKim: “You have always credited me with having a sense of what constitutes the monumental in sculpture and I think this is it!”

Daniel Chester French (1850–1931)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 April 1904

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

The Sculptor O'Connor

The Irish American artist Andrew O’Connor was commissioned to execute much of the Library’s exterior relief sculpture, but his contract was scaled back when he failed to work quickly enough to satisfy McKim and Morgan. This telegram (sent from Paris, where O’Connor kept a studio) conveys the sculptor’s own frustration.

After O’Connor was relieved of his commission for the rectangular reliefs, Adolph Weinman stepped in to design them. O’Connor ultimately completed the dedicatory panel supported by winged angels and the tympanum featuring the mark of the Aldine Press.

Andrew O’Connor (1874–1941)

Telegram to Charles Follen McKim, Paris, 21 November 1904

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

"I Saw Your Morgan Library; It is a Peach"

In the summer of 1905, as McKim rushed to finish the Library by the agreed-upon date of 1 October, the architect had a breakdown. His good friend Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a prominent sculptor, sent this letter of encouragement. How should McKim respond to Morgan’s incessant demands? “I think if you were to sass him back he would respect you more,” Saint-Gaudens advised.

McKim had been juggling multiple demanding projects (including New York’s massive new Pennsylvania Station) and took some time to rest. A few months later, Saint-Gaudens told a friend, “We were nervous about him, but are now glad to see he is in harness again.”

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, 23 August 1905

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Mckim's Grand Proposal (1)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 1

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Mckim's Grand Proposal (2)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 2

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Mckim's Grand Proposal (3)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 3

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Mckim's Grand Proposal (4)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 4

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Mckim's Grand Proposal (5)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 5

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Mckim's Grand Proposal (6)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 6

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Mckim's Grand Proposal (7)

McKim sent this carefully worded letter to Morgan in early 1904, two years after he was commissioned to design the Library. He asked for a meeting to present the interior designs along with a comprehensive cost estimate. To mark the Library’s association with the Italian Renaissance, McKim proposed that the front doors be surmounted with a marble bas-relief incorporating the trademark of Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian scholar-printer who founded the Aldine Press in 1494.

Morgan approved the designs and the budget. He retained this letter, one of only a handful between the two men to survive.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Letter to J. Pierpont Morgan, New York, 28 February [1904], page 7

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Twenty-One Shelves of Aldines

McKim chose to incorporate this printer’s symbol into the bas-relief marble over the doors of Morgan’s Library: a dolphin spiraled around an anchor, the mark of the Aldine Press, the legendary Venetian house founded by Aldus Manutius at the turn of the sixteenth century. It was an appropriate choice. In 1899 Morgan had acquired some 220 Aldines (including this edition of the works of the Roman poet Ovid) as part of his purchase of the extraordinary library of London bookdealer James Toovey (1814–1893). The London Times reporter who visited Morgan’s Library in 1908 enthused, “Aldines? There are twenty-one shelves of them.”

Ovid (43 BC–AD 17 or 18)

Opera

Venice: Aldo Pio Manuzio, 1502–3

The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan with the Toovey Collection, 1899; PML 1508