The Builders

The stoneworkers pictured here are among the hundreds of people, their names largely unknown to us today, who built the bookman’s paradise. They were photographed in a Bronx shop full of intricately carved marble blocks destined for the loggia of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library. Charles Follen McKim, the lead architect and creative force behind the Library, relied on a team of proficient drafters in McKim, Mead & White’s studio to create the drawings that articulated his vision. He engaged Charles T. Wills as general contractor and a host of specialists to build and ornament the Library. Just after construction began in 1903, a series of strikes brought the entire New York building industry to a standstill. Progress on the Library was delayed as workers sought improved conditions and better pay.

Stone carvers in the shop of Robert C. Fisher & Co., late 1904 or 1905. Museum of the City of New York, 90.44.1.675

An Italian Renaissance Precedent

As McKim developed his plans for the Library’s façade (and, later, the interiors), he made ample reference to Italian buildings designed for the political and financial elites of the Renaissance. He thus positioned Morgan as their American heir. The entry to the sixteenth-century Villa Medici, designed largely by Bartolommeo Ammannati, was a notable architectural source.

James Anderson (1813–1877)

The Villa Medici, Rome, 1865

Albumen print

Collection of W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg

The Building Blocks of Morgan's Library

The first exterior elevations of the Library were created in March 1903 by a drafter who signed “Stevens”—likely Gorham P. Stevens, who worked for McKim, Mead & White before departing to serve as the inaugural architectural fellow at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. Once construction of the Library was underway, McKim would send Stevens several squeezes (molds) of the spaces between the marble blocks, telling him, “Our vertical joints are nearly, if not quite, as good as the best of the Greek, it being impossible to insert a knife blade between them.”

Note the maned lion depicted at the Library’s entrance. The sculptor Edward Clark Potter would ultimately produce lionessses instead.

Probably Gorham P. Stevens (1876–1963) for McKim, Mead & White

East Elevation, Library Building for J. P. Morgan, Esq., 3 March 1903

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

McKim and the American Academy in Rome

In 1901 McKim sought Morgan’s endorsement for a cherished project: a new academy in Rome that would serve as a classical training ground for American artists and architects. Morgan agreed to join fellow collector and businessman Henry Walters in a public declaration of support. A few months later, in early 1902, Morgan invited McKim to his home for breakfast and asked him to design his Library.

Morgan ultimately joined Walters in providing significant financial support for the American Academy in Rome, which would become a major international center for scholarship and creative exchange. It still thrives today.

W. Kurtz, New York

Charles Follen McKim, ca. 1880s

Cabinet photograph

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

McKim to Mead: "The Office [is] Prospering"

“I think you will agree [that] the office [is] prospering, when I tell you of the several new jobs in hand, as well as in prospect,” McKim wrote to his business partner William Rutherford Mead in April 1902. One architectural commission McKim, Mead & White had just secured was New York’s monumental new Pennsylvania Station, which would open in 1910. Another, McKim explained, was from Morgan, who wanted to “build a little Museum building to house his books and collections.”

C. L. Howe & Son, Brattleboro, Vermont

William Rutherford Mead and Charles Follen McKim, ca. 1890s

Cabinet photograph

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

What Morgan Wants . . . (1)

In the early stages of the design process, J. Pierpont Morgan’s son-in-law Herbert Satterlee took the lead in communicating with McKim, passing on information gleaned from Junius S. Morgan II, Pierpont’s nephew and adviser.

Here, Satterlee made clear that the new building would house “a collection of rare volumes,” rather than a “reading library.” Estimating that Pierpont already held about ten thousand volumes, Satterlee instructed McKim to plan for growth and incorporate a librarian’s office.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 19 May 1902, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

What Morgan Wants . . . (2)

In the early stages of the design process, J. Pierpont Morgan’s son-in-law Herbert Satterlee took the lead in communicating with McKim, passing on information gleaned from Junius S. Morgan II, Pierpont’s nephew and adviser.

Here, Satterlee made clear that the new building would house “a collection of rare volumes,” rather than a “reading library.” Estimating that Pierpont already held about ten thousand volumes, Satterlee instructed McKim to plan for growth and incorporate a librarian’s office.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 19 May 1902, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

. . . Morgan Gets (1)

Louisa and Herbert Satterlee (Morgan’s daughter and son-in-law) sailed to England in summer 1902 to join Morgan for the coronation of Edward VII. They brought along McKim’s first designs for the Library. In this letter, Satterlee conveyed Morgan’s response to McKim: “They did not prove to be just what he wanted.”

Satterlee outlined Morgan’s wishes but reassured McKim: “I have formulated his objections with brutal brevity & ought to say that he liked the dignity of your building & its purity of design.” McKim went back to the drawing board, and by the end of the summer he had completed a design that Morgan embraced.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, Aldenham Abbey, Watford, Hertfordshire, England, 29 July 1902, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

. . . Morgan Gets (2)

Louisa and Herbert Satterlee (Morgan’s daughter and son-in-law) sailed to England in summer 1902 to join Morgan for the coronation of Edward VII. They brought along McKim’s first designs for the Library. In this letter, Satterlee conveyed Morgan’s response to McKim: “They did not prove to be just what he wanted.”

Satterlee outlined Morgan’s wishes but reassured McKim: “I have formulated his objections with brutal brevity & ought to say that he liked the dignity of your building & its purity of design.” McKim went back to the drawing board, and by the end of the summer he had completed a design that Morgan embraced.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, Aldenham Abbey, Watford, Hertfordshire, England, 29 July 1902, page 3

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

. . . Morgan Gets (3)

Louisa and Herbert Satterlee (Morgan’s daughter and son-in-law) sailed to England in summer 1902 to join Morgan for the coronation of Edward VII. They brought along McKim’s first designs for the Library. In this letter, Satterlee conveyed Morgan’s response to McKim: “They did not prove to be just what he wanted.”

Satterlee outlined Morgan’s wishes but reassured McKim: “I have formulated his objections with brutal brevity & ought to say that he liked the dignity of your building & its purity of design.” McKim went back to the drawing board, and by the end of the summer he had completed a design that Morgan embraced.

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (1863–1947)

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, Aldenham Abbey, Watford, Hertfordshire, England, 29 July 1902, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

"The Sky is Blue and There is No Occasion for Worry"

Nearly four years after Morgan had invited McKim to design his Library, the building was substantially complete. McKim wrote to his partner Stanford White to express pleasure and relief. Morgan had been a demanding client, and the work had taken a toll on McKim.

Though White had secured an antique ceiling for Morgan’s Library, he was not involved in the building’s design. Five months after he received this letter, White was murdered at Madison Square Garden, one of his own creations.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Retained copy of a letter to Stanford White, New York, 1 February 1906

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

The Property Survey

This survey, created at the time of excavation, provides a detailed overview of the block on which the Library would be built. Morgan and his second wife, Fanny, lived at 219 Madison, on the northeast corner of 36th Street and Madison Avenue. The new Library would be constructed half a block to the east, on 36th Street between Madison and Park, where the large blank space appears on the map.

Francis W. Ford (1846–1904)

Survey of the block between 36th and 37th Streets and Madison and Park Avenues, New York, 17 October 1902

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

East Tennessee Stone

The lead builders of Morgan’s Library traveled to Tennessee in 1902 to scout stone. They chose to buy from the Knoxville Marble Company, run by John M. Ross, who was able to supply a large quantity of attractive and uniform stone. Morgan selected from several samples presented for his inspection. The heavy blocks were transported to New York via train—on the very railroads Morgan’s financial firm had reorganized through a nineteenth-century syndicate.

On this geologic map, Knoxville appears in the second colored band from the right at about 36° latitude, 84° longitude. The area is marked with the word “MARBLE.”

Nelson Sayler

An Outline Geological Map of Tennessee, Including Portions of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia

Cincinnati: E. Mendenhall, 1866

Library of Congress

Stoneworkers' Wages

Virtually no records exist of the wages paid to the many people who built Morgan’s million-dollar Library. This letter is a rare exception: it lists typical day rates for various categories of workers employed by the stone contractor.

Skilled carvers were some of the higher-paid tradespeople, earning $5.50 per day. At the other end of the spectrum, laborers hoisting the stones on-site earned fifty cents a day under the employment of William Angus (a Scottish immigrant whose firm set the marble blocks). For comparison: the artist Hughson Hawley billed at a daily rate of $25 for his work on the watercolor rendering of the Library shown elsewhere in this exhibition; Beatrix Farrand, the landscape designer, charged $50 a day plus expenses.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Page from a letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 7 February 1903

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

The Completed Library

From 1902 to 1906, hundreds of people worked to fulfill Morgan’s commission and realize McKim’s design, from the quarriers who extracted the stone in East Tennessee to the masons who set the blocks with exquisite precision. More than a century later, a contemporary team of specialists has honored their labor by restoring this well-made building, cleaning and repairing the façade, statuary, and front doors as well as the bronze perimeter fence shown in this early photograph.

Pach Brothers, New York

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1910

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 3278.1

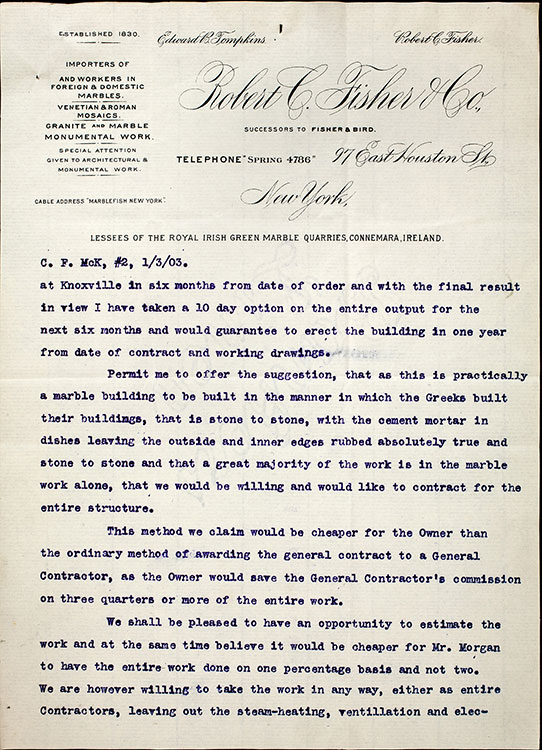

Building Without Mortar (1)

Robert C. Fisher & Co. secured the major contract to handle the exterior stonework (both construction and carving) for Morgan’s Library. In this letter, the firm’s president reported on his excursion to Knoxville, Tennessee, to source marble for the project. He called attention to the challenges inherent in McKim’s request to set the stone blocks without mortar: “This will be the only building ever built in modern time[s] as the ancients built and will require, as was required of them, the utmost accuracy and nicety known in mechanics.”

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 3 January 1903, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Building Without Mortar (2)

Robert C. Fisher & Co. secured the major contract to handle the exterior stonework (both construction and carving) for Morgan’s Library. In this letter, the firm’s president reported on his excursion to Knoxville, Tennessee, to source marble for the project. He called attention to the challenges inherent in McKim’s request to set the stone blocks without mortar: “This will be the only building ever built in modern time[s] as the ancients built and will require, as was required of them, the utmost accuracy and nicety known in mechanics.”

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 3 January 1903, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Building Without Mortar (3)

Robert C. Fisher & Co. secured the major contract to handle the exterior stonework (both construction and carving) for Morgan’s Library. In this letter, the firm’s president reported on his excursion to Knoxville, Tennessee, to source marble for the project. He called attention to the challenges inherent in McKim’s request to set the stone blocks without mortar: “This will be the only building ever built in modern time[s] as the ancients built and will require, as was required of them, the utmost accuracy and nicety known in mechanics.”

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 3 January 1903, page 3

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

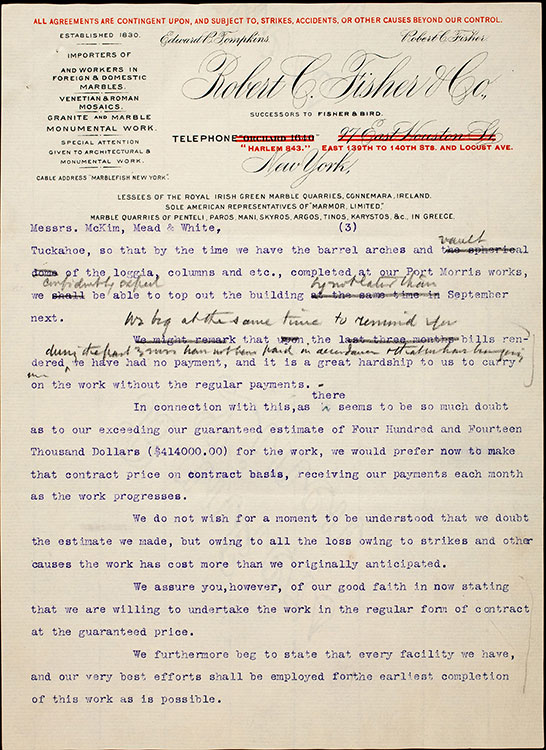

Untenable Working Conditions (1)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 1

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Untenable Working Conditions (2)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 2

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Untenable Working Conditions (3)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 3

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Untenable Working Conditions (4)

Just after construction had begun, a wave of strikes in the building trades brought work to a halt. By the time matters were resolved, freezing temperatures made it next to impossible to operate the stone shop. The marble contractor was forced to maintain enormous cash outlays, and McKim, Mead & White was withholding payment because work was behind schedule. Tompkins, the president of the marble contracting firm, outlined the dire situation in this letter to McKim.

In the end, these challenges and others (including unanticipated costs associated with the unorthodox stone-setting method McKim had stipulated) forced Fisher & Co. to mortgage its property for $80,000. The firm—one of the most distinguished in the trade—went bankrupt in 1911 after another wave of strikes.

Edward B. Tompkins (1850–1907), president of Robert C. Fisher & Co.

Letter to Charles Follen McKim, New York, 18 February 1904, page 4

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

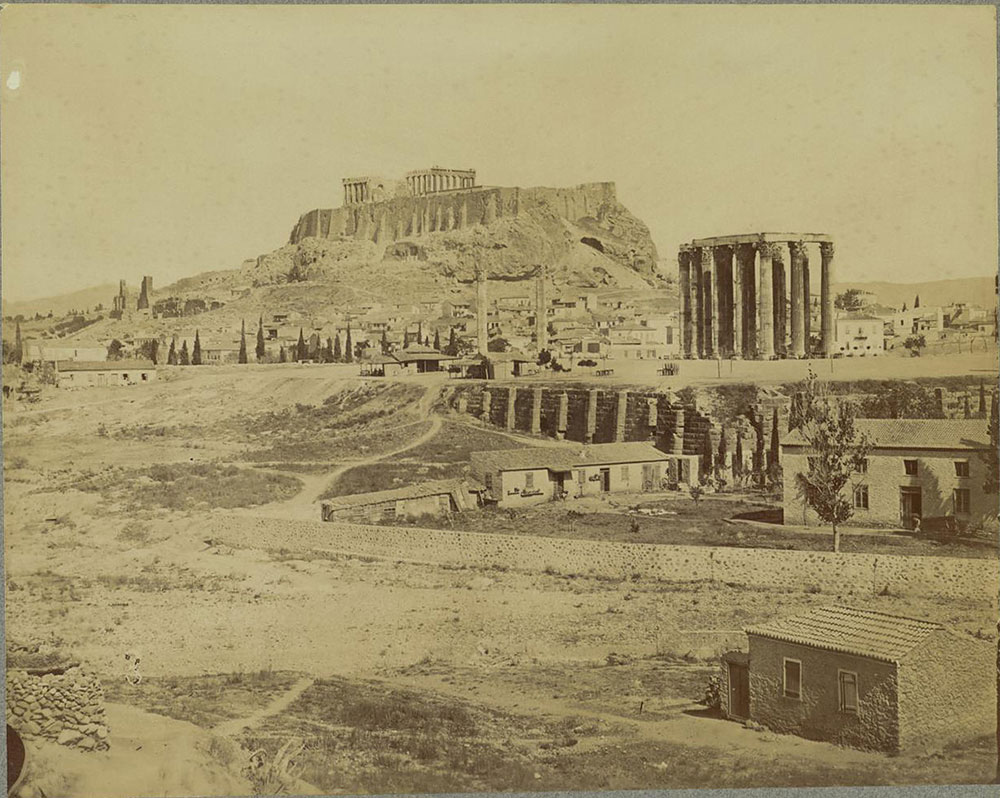

Inspired by the Ancients

McKim was dazzled by the buildings on the Acropolis in Athens. The stone blocks of the fifth-century-BC Erechtheum lined up face-to-face, mortarless, with such precision that even a thin blade could not be slipped into the seam. When he was engaged to design Morgan’s Library, McKim convinced the marble contractor, Robert C. Fisher & Co., to adapt ancient stone-setting methods, and Morgan agreed to cover the substantial additional cost.

These photographs, from a travel scrapbook in McKim, Mead & White’s records, depict the ancient architecture McKim so admired as he sought to create a contemporary building of comparable excellence.

Photographs from a McKim, Mead & White scrapbook depicting the Erechtheum and the Athenian Acropolis, ca. 1890s

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

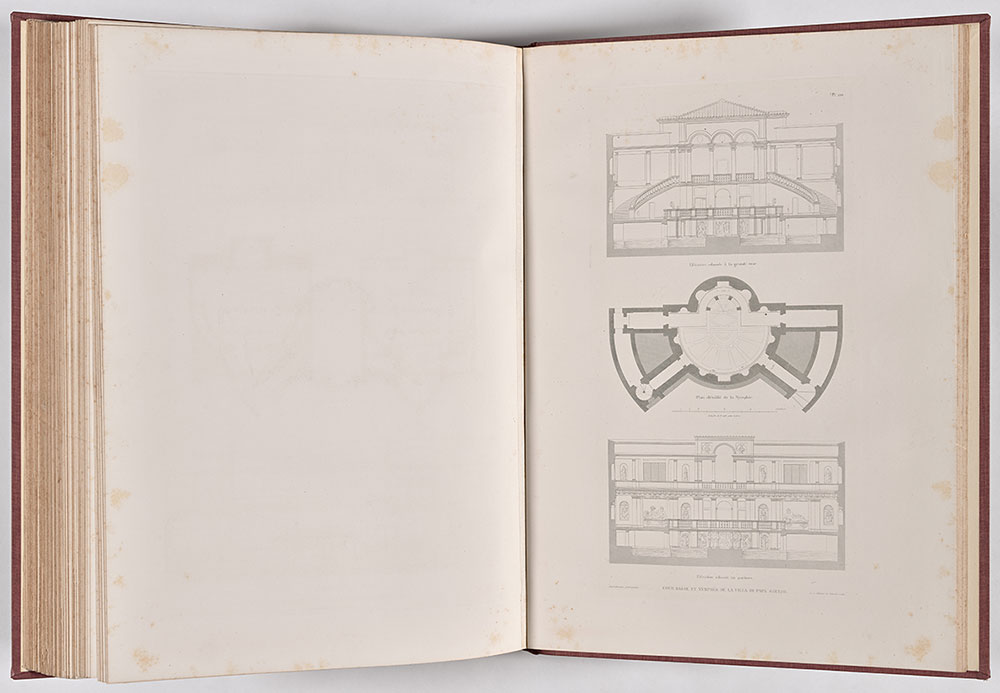

Mckim's "Office Bible"

McKim, Mead & White held an impressive library that informed its design practice. McKim himself relied heavily on the nineteenth-century French architect Letarouilly’s compilation of line drawings of Roman buildings. This plate depicts the nymphaeum of the sixteenth-century Villa Giulia, designed largely by Bartolommeo Ammannati. The Renaissance building was a key historic precedent for the façade of Morgan’s Library. McKim inscribed this copy to nineteen-year-old Lawrence Grant White, son of Stanford White, in 1906—just as Morgan’s Library was being completed and not long after Lawrence’s father was murdered. Lawrence was then an undergraduate at Harvard; he would go on to join the firm and have a distinguished architectural career himself.

Paul Letarouilly (1795–1855)

Édifices de Rome moderne; ou recueil des palais, maisons, églises, couvents, et autres monuments publics et particuliers les plus remarquables de la ville de Rome, vol. 2

Paris: Morel et Cie, 1874

Avery Classics Collection, Columbia University

Built on Lenape Land

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library stands on land that is part of Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Lenape people. The marble blocks of which the Library was constructed were quarried on the ancestral lands of the ᏣᎳᎫᏪᏘᏱ Tsalaguwetiyi (Cherokee, East) and S’atsoyaha (Yuchi) peoples.