The East Room

J. Pierpont Morgan left no written record of how he wanted his library-within- the- Library to look or the cultural values he wished it to convey. But we know he was satisfied with the showplace Charles Follen McKim delivered. The completed East Room is an American homage to European creativity and a conspicuous display of wealth. To the London Times correspondent who visited in 1908, it was paradise. “Here, at last,” they wrote, “is the ideal library, the ideal setting for noble books.”

A sixteenth-century tapestry serves as the focal point of the room. Several of the bookcases swing open to reveal hidden staircases that provide access to the second and third tiers of shelves. Above it all is an extravagant ceiling. But surrounded as they are by this profusion of ornament, it is the books—some fourteen thousand of them—that define the room.

Envisioning a Library

This rendering of McKim, Mead & White’s early vision for one of the East Room walls bears only a hint of resemblance to the finished space. While the coved ceiling with its series of painted lunettes and spandrels would remain, the scenes depicted here would be replaced with murals of an entirely different design. There would be no patterned red wall coverings. Instead of a single continuous bookcase ringing the room, there would be three, one atop the other, creating a wall of books.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Preliminary design for the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:10

The Approved Design

Morgan approved this plan for the East Room of his Library in 1904, and the room was constructed as depicted, though major changes would be introduced in the final stages.

Here, the lunettes are all marked “painting,” to note where ceiling murals by the artist H. Siddons Mowbray would be installed. At top left, the words “Guastavino construction” indicate that the vaulted ceiling would be erected by the firm established by Rafael Guastavino, an immigrant from Spain known for his innovative tiling method. The Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini would supply the stone mantelpiece, though the ornamental top would later be lopped off to make way for a sixteenth-century tapestry.

August Reuling (1884–1966) for McKim, Mead & White

Section through East Room Looking East, Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., 3 June 1904

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Under Construction

It is astonishing that construction proceeded this far before it became clear that the East Room would not come close to accommodating Morgan’s vast collection of rare books. The shelving contractor, anticipating this outcome, had reinforced the Circassian-walnut bookcases “with tee irons sufficiently strong to carry two stories above when the growth of the library has made such expansion necessary.” That moment arrived in 1906, just as McKim thought the building was nearing completion.

The Library was thrust back into construction mode. The windows depicted here were covered with new bookcases, and the corresponding openings in the faultless exterior were filled in with additional marble blocks.

Pach Brothers, New York

The East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library under construction, ca. 1906

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1578

The Completed Library

Cabinetmakers and builders added two tiers of bookcases during the final stages of construction. Instead of a grand room that happened to house books, the East Room of Morgan’s Library was thus transformed into a space whose function was unmistakable. Long study tables and lecterns were custom-made for the room. In 1911 (after McKim had died), Morgan acquired the sixteenth-century German sculpture of a saint, possibly Elizabeth of Schönau. She is depicted—appropriately—with book in hand.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Photograph

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1601.1

Mowbray's Reclining Women

Though women were depicted prolifically inside the bookman’s paradise, they appeared most often as allegorical, rather than historical, figures. In nine of the East Room’s ceiling lunettes, Mowbray painted lounging female figures representing tragedy, comedy, painting, architecture, poetry, history, music, science, and astronomy. He took inspiration from the four sibyls (women prophets) portrayed by Pinturicchio in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. Mowbray told the architects that his color scheme would evoke “the softened harmony and patina of an old room,” with gold accents conveying “the tonal quality of an old Florentine frame.”

H. Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928)

Study for the figure of Music in the ceiling of the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1904 or 1905

Graphite

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mrs. Harry S. Mowbray; 1981.75:2

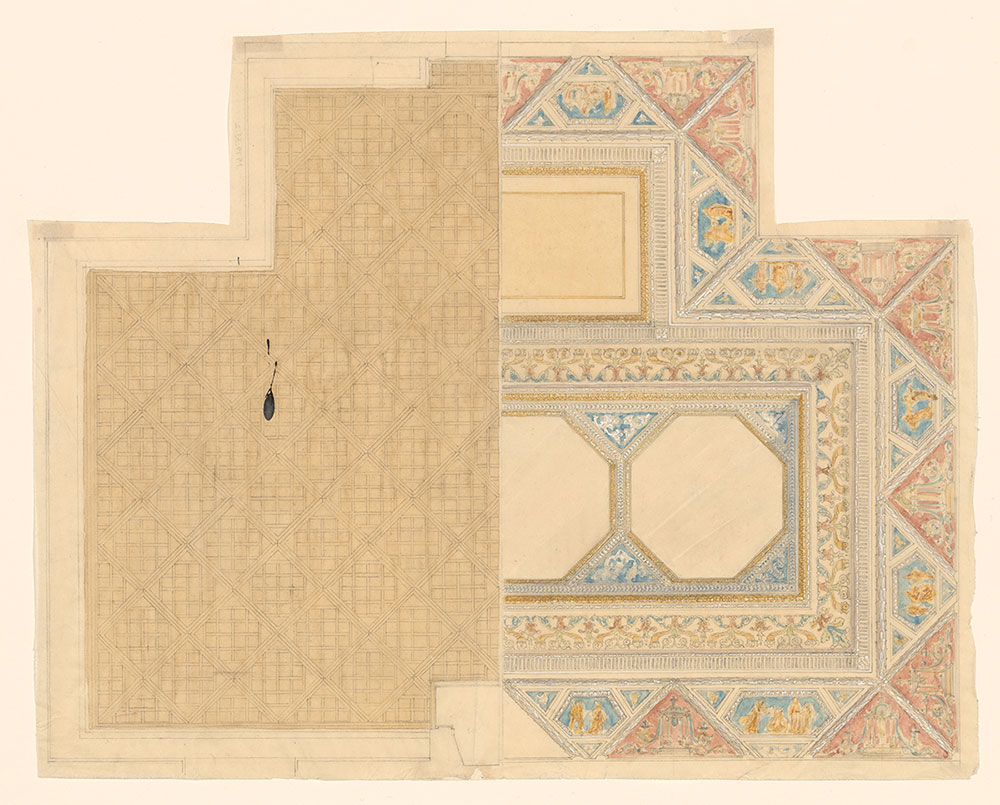

Ceiling and Floor

The left half of this drawing is an early outline for the East Room’s ornate ceiling; the right side depicts the design for the space’s parquet floor. While the color scheme and decorative details would evolve, this ambitious plan for the ceiling was carried out. The floor, too, was laid essentially as shown—replicating the oak parquet that had recently been installed during McKim, Mead & White’s renovation of the White House.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Design for the floor and ceiling of the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1904

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1979.33:3

Presidential Parquet

McKim, Mead & White’s 1902 renovation of the White House included G. W. Koch & Son’s oak parquet floors, which President Theodore Roosevelt's children found to be a convenient surface for roller-skating. Here, the same contractor placed a bid to lay floors in Morgan’s Library in precisely the same style. He later submitted a revised, successful bid of $2,700, along with this explanation:

We have not figured this work to see how cheaply we could do it, but have made out prices so that we can afford to do this work in the very best manner possible, both as to workmanship, and material, as we presume that Mr. Morgan will appreciate quality more than he will price.

G. W. Koch & Son

Bid for flooring for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 18 February 1904

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

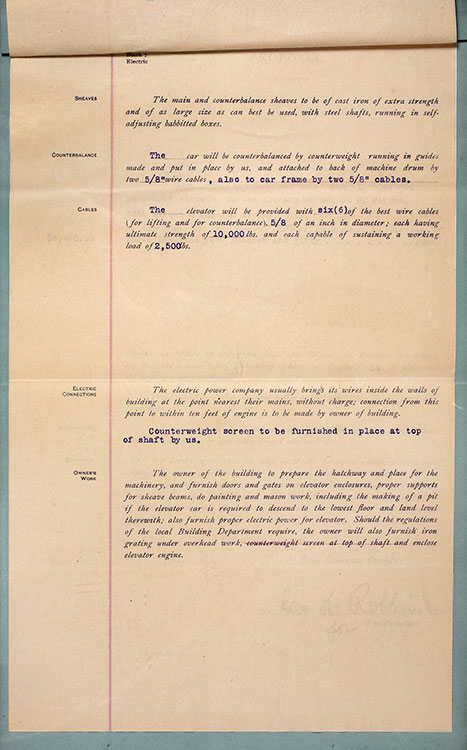

An Otis Elevator

While McKim designed Morgan’s Library in an Italian Renaissance style and adapted ancient Greek construction techniques, the building was very much a contemporary creation. The Otis Elevator Company installed an electric engine in the cellar and created an elegant passenger car to the architects’ specifications. Electrical fixtures were added to the car by the firm Edward F. Caldwell & Co. More than a century later, the elevator is still used by staff.

Otis Elevator Company

Specifications for Standard Electric Passenger Elevator for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 13 June 1904

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

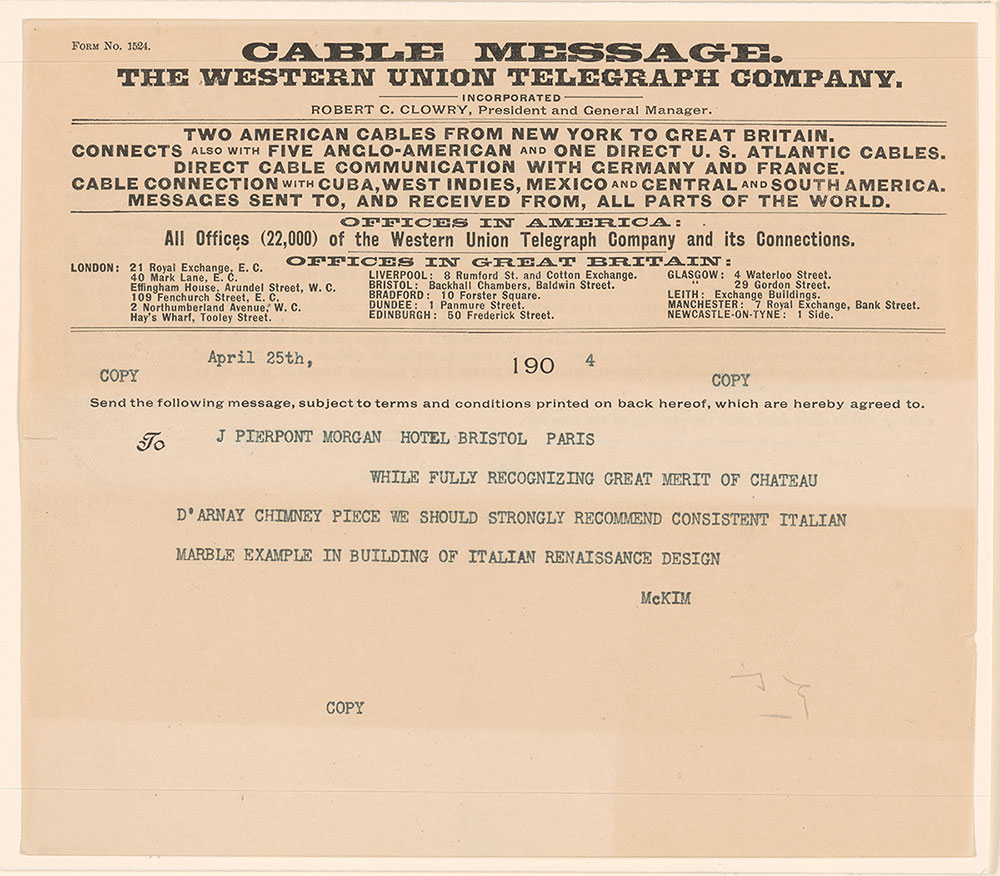

Architect and Client

While traveling in Europe and meeting with dealers in 1904, Morgan learned of the availability of a sixteenth-century French mantelpiece he had seen illustrated in Claude Sauvageot’s book Palaces, Castles and Residences in France. He wired McKim to alert him. In this response, the architect was deferential but firm: this French component had no place in a building “of Italian Renaissance design.”

McKim prevailed. All the mantels ultimately installed in the Library would be Italian antiques. New York tradespeople initially refused to set them because the stone had not been cut by union laborers, but the matter was resolved.

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909)

Telegram to J. Pierpont Morgan, 21 November 1904

Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Designing the East Room Ceiling

August Reuling, a drafter for McKim, Mead & White, created the meticulous drawing that would guide the builders and artisans who would model, paint, and gild the extensive ornamental detail in the East Room ceiling. The three octagonal shapes represent the three laylights (large, flat pieces of semitransparent leaded glass) that would illuminate the room.

August Reuling (1884–1966) for McKim, Mead & White

Plan of Ceiling, East Room, Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., 19 May 1904

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

Poetry Through the Ages

As he developed designs for the three lunettes (the semicircular paintings over the principal doors) in the Rotunda, Mowbray consulted a volume that reproduced Pinturicchio’s fifteenth-century decoration of the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican. Taking the Italian painter’s work as a point of departure, Mowbray populated the Morgan lunettes with familiar figures from ancient, medieval, and Renaissance poetry. In the mural over the Library’s front doors, the central altar is flanked by King Arthur (at left, with his lance and the Holy Grail) and Beatrice (Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s beloved, at right). The trompe-l’oeil archway above provides the illusion of depth.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

South lunette in the Rotunda of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1782

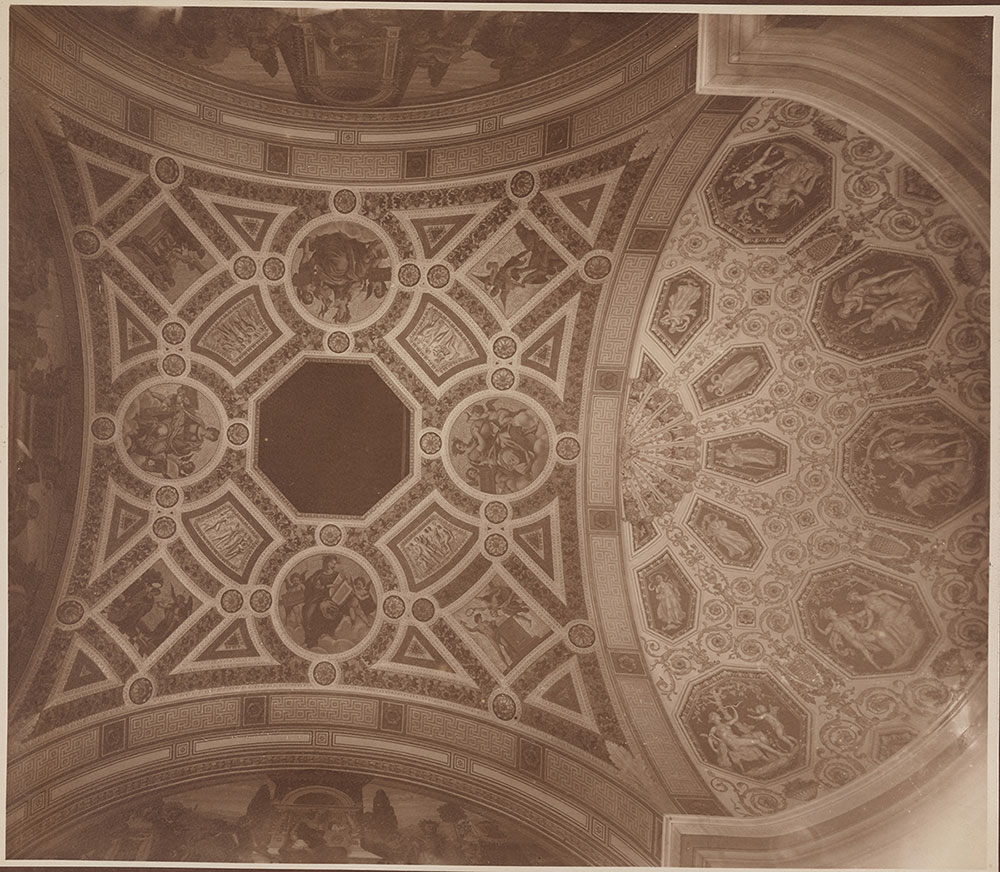

Mowbray's Ceiling Murals

In a series of lunettes (paintings in the shape of a half-circle) for the East Room ceiling, the artist H. Siddons Mowbray alternated depictions of nameless women with portraits of specific historical men, each representing a field of knowledge or creativity. Here, the female figure personifying music appears next to a portrait of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

Mowbray was one of the most generously paid contributors to Morgan’s Library. For his work on the East Room and Rotunda ceilings, Mowbray earned $46,406. The architectural firm McKim, Mead & White earned a total commission of $59,700 (5 percent of building costs, plus 10 percent of special costs); Charles T. Wills, the project’s general contractor, was paid $30,000.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

Ceiling murals in the East Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1777