The West Room

“It is no impression of ostentation that one obtains upon entering,” wrote the London Times correspondent who visited the Library in 1908, “but one of exquisite, peaceful chambers in which a man superlatively fortunate may pass his hours divinely.” While ostentation (or lack thereof) may be in the eye of the beholder, J. Pierpont Morgan was certainly a fortunate man. He spent many hours here in his private study, smoking Cuban cigars, playing solitaire, and receiving guests.

Every available space was filled with splendid things: custom-made furniture in a sixteenth-century Italian style, small-scale artworks atop the low walnut bookcases, treasure bindings propped on tabletops, and oil paintings hung on the silk-covered walls or affixed to freestanding easels. A steel-lined vault housed medieval and Renaissance manuscripts as well as modern literary manuscripts and letters. The room itself combined antique elements with new, positioning its inhabitant as a latter-day Renaissance prince capable of acquiring, or commissioning, whatever he fancied.

Inside the Vault

Arnold Genthe was the first to photograph Morgan’s study in color, using a new technology invented by the French brothers Lumière. The completed glass plates, called autochromes, could be viewed with a hinged stand called a diascope, which incorporated a mirror that reflected the color image. Morgan was so pleased with Genthe’s work that he ordered multiple diascopes mounted into fine leather cases. Genthe later recalled the unusual circumstances of the shoot:

During the long exposure of the plates I was permitted to go into the vault where the rare and precious manuscripts were kept and to study those in which I was particularly interested. This of itself would have been ample compensation to me.

Arnold Genthe (1869–1942)

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1912

Color print, 1935, made from 1912 autochrome

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1586

An Art-Filled Study

Prominently displayed on the easel pictured here is one of several major works that Morgan purchased in 1907 (for a total of $2 million) from the estate of the German-born Parisian banker Rodolphe Kann. It is a fifteenth-century portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni by the Florentine artist Domenico Ghirlandaio. In the painting, depicted just behind the subject is a gilt-edged Renaissance-era prayer book much like those Morgan housed in the West Room’s vault.

Morgan’s son, Jack, sold the painting in the 1930s; it is now in the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. Three panels by the fifteenth-century Flemish master Hans Memling, which Morgan also acquired from the Kann estate, remain in the room today.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1612.1

On the Eve of Move-in

During much of 1905 and into 1906, contractors and decorators scrambled to complete the interiors of Morgan’s Library. Here, the bookcases around the perimeter of his study have already been filled with gilt-lettered volumes. The shelves inside the steel-lined vault at right, however, remain empty, ready to receive Morgan’s collection of manuscripts.

The silk damask wall coverings incorporate images of an eight-point star and a pyramid-shaped cluster of six hills, elements of the heraldic arms of the Chigi family, powerful Sienese bankers of the Italian Renaissance. It is unclear how many of Morgan’s guests would have noted the reference.

Pach Brothers, New York

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library just after construction, ca. 1906

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1581

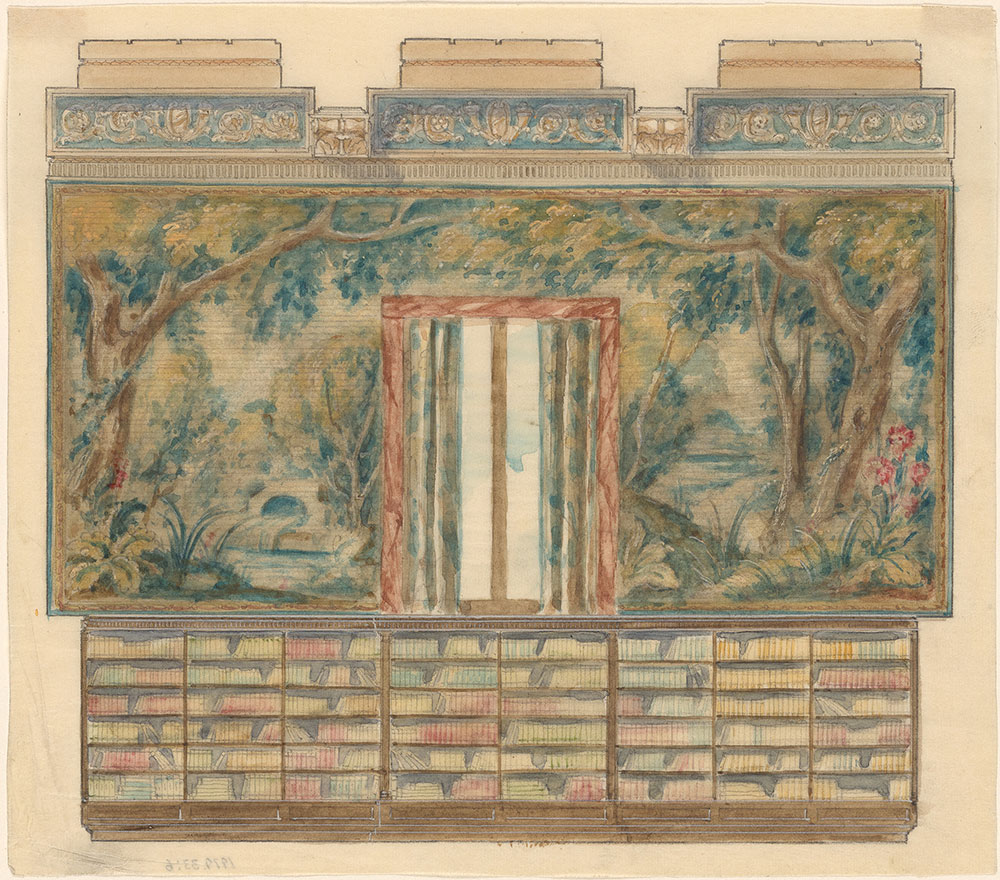

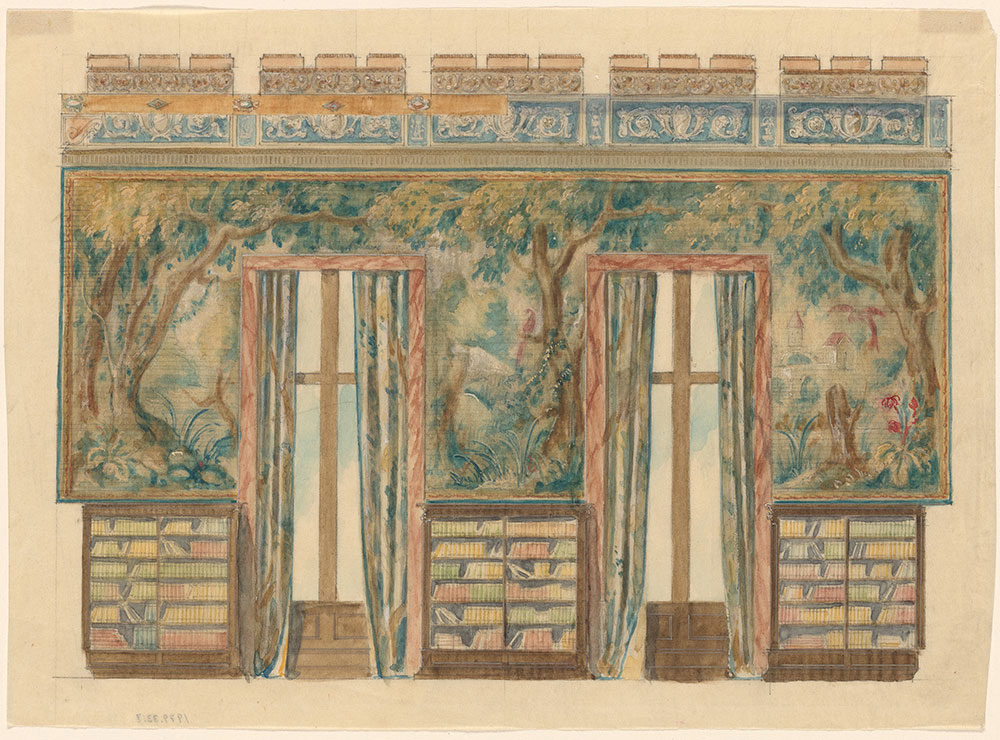

A Vision for Morgan's Study

McKim considered this verdant look for Morgan’s study during the early stages of interior design. But after viewing the art gallery in Lynnewood Hall, the Philadelphia-area mansion of industrialist Peter A. B. Widener, McKim shifted course. “You were kind enough to say last week,” McKim wrote to Widener, “that you would be glad to have Mr. Morgan avail himself of your experience in the selection of a material for the covering of the walls of one of the rooms in the library which we are building for him.” McKim secured fabric samples from Widener’s supplier and ultimately selected a crimson silk with a raised pile, which proved a more suitable backdrop for works of art.

For McKim, Mead & White (artist unknown)

Early designs for the West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1904

Graphite, watercolor, and tempera

The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Mr. Walker O. Cain in honor of Charles Ryskamp on his 10th anniversary as Director; 1979.33:6–7

The Financier's Desk

The London decorator A. Barnard Cowtan told Morgan’s librarian, Belle da Costa Greene, that he had “well over one hundred men” working “nearly all night” to complete a large furniture order for the Library toward the end of 1906. For Morgan’s desk and other pieces, Cowtan’s designers drew inspiration from sixteenth-century Italian examples in the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A, London). Greene and assistant librarian Ada Thurston received custom-made desks and other bespoke office furniture as well.

The telephone may look out of place in a room that evokes Renaissance splendor, but it was very much a part of everyday business for both Morgan and Greene.

Tebbs & Knell, New York

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1923–ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 1619

"Woman Sewing the Velvet"

This six-page invoice, totaling £5,203, details the custom-made tables, desks, stools, table coverings, and other furniture pieces and adornments supplied by the venerable London firm Cowtan & Sons. Some pieces were shipped from London to be upholstered in New York, using 127 yards of antique velvet that Morgan had secured.

The last line item is a charge of £91 for the on-site work of the upholsterers, “including woman sewing the velvet.” This passing reference documents one of the very few women (albeit an unnamed one) who worked for a contractor inside the bookman’s paradise.

Cowtan & Sons, London

Statement of expenses issued to J. Pierpont Morgan, 1906

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives

Electric Light and a Burning Fire

This early view of Morgan’s study by the Austrian-born artist Emil Fuchs conveys a key characteristic of the room: its free juxtaposition of old and new. The mantelpiece is a composite of a fifteenth-century lintel and new components. The coffered wooden ceiling comprises new and antique elements as well as painted embellishments by the contemporary artist James Wall Finn. As a fire burns below, electric lights (including the hanging fixture with an alabaster shade) illuminate the room. While sixteenth-century majolica plates were placed atop the bookcases, the fireplace was crowned with a contemporary oil portrait depicting Morgan’s father, the banker Junius Spencer Morgan.

Emil Fuchs (1866–1929)

The West Room of J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, ca. 1907–8

Oil on panel

The Morgan Library & Museum, transfer from the Brooklyn Museum, 2018; AZ204