The Facade

Situated on an urban residential block, J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library appears strikingly distinct yet surprisingly at home. Architect Charles Follen McKim drew on Italian Renaissance precedents to design a contemporary American building that conveyed power and permanence, intimacy and grandeur. “Above all,” he told his client, “we are desirous that the design shall represent your views and reflect your judgment, in order that it may become a worthy monument to your munificence and public spirit.”

The building was complete by 1906, and Morgan was satisfied. Daniel Chester French, the prominent sculptor, stopped by to see it and wrote to reassure the exhausted McKim: “Of course Mr. Morgan likes his library. Who would dare not to?”

Plan View of Warren's Unbuilt Library-museum

There are no records of Warren’s discussions with Morgan about the program for the new Library, but this drawing suggests that Warren and Charles Follen McKim received similar instructions. Both Warren’s unbuilt design and McKim’s realized plan include a central rotunda, a grand library space, and two smaller offices. Though Warren’s drawings reference a “Library-Museum,” Morgan ultimately clarified that his new building would most emphatically be a library rather than a “picture gallery.”

Whitney Warren (1864–1943)

For J. P. Morgan Esq. / Sketch Plan for Library Museum, before March 1902

Graphite, pen and black ink, blue and yellow watercolor, and red and green crayon

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Mrs. William Greenough; 1943-51-334

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NY

Whitney Warren’s Sketch for a "library-museum"

As commodore of the New York Yacht Club, Morgan served on the committee that selected architect Whitney Warren’s ambitious designs for the new clubhouse that opened in 1901 on West 44th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. It may have been around that time that Morgan asked Warren to draw up these undated plans for his Library. There is no record of Morgan’s response; we only know that he chose not to engage Warren and turned instead to Charles Follen McKim.

Whitney Warren (1864–1943)

For J. P. Morgan / Front / Sketch for Library-Museum, before March 1902

Graphite and colored pencil

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Mrs. William Greenough; 1943-51-401

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NY

Warren's Refined Design

In this more formal elevation, Warren proposed an ornate Beaux-Arts-inspired “Library-Museum,” its entrance flanked by figures representing art and wisdom, water gushing from open-mouthed lions at the pedestals’ feet. Morgan did not pursue Warren’s designs and offered the commission to Charles Follen McKim. Warren was displeased, and he let McKim know it. Warren would visit Morgan in the completed Library in 1908 but apparently held his grudge. As late as 1930 he stated publicly that McKim had taken the Library from him and boasted that he had evened matters by securing a commission McKim, Mead & White had also sought: Grand Central Terminal.

Whitney Warren (1864–1943)

Front Elevation / Proposed Library-Museum for J. Pierpont Morgan Esq. New York, before March 1902

Graphite

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Mrs. William Greenough; 1943-51-332

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NY

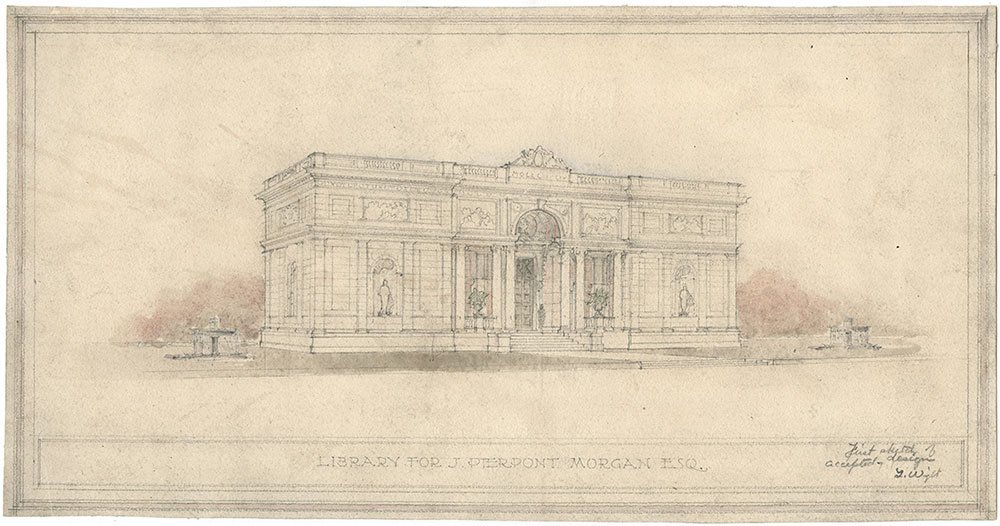

The Approved Design

This drawing, marked “First sketch of accepted design,” was made not by the lead architect, Charles Follen McKim, but by his twenty-seven-year-old employee Thomas Wight. This was not unusual: McKim was known for relying on the firm’s studio drafters while providing strong design leadership.

As a teenager newly arrived from Nova Scotia in the 1890s, Wight had answered an advertisement for a “boy” to work with McKim, Mead & White in Boston. “I want the job, but I don’t want to be a boy,” he said, insisting there be room for advancement. There was. Wight left the firm before the Library was completed to establish his own successful architectural practice in Kansas City, where he would design the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Thomas Wight (1874–1949) for McKim, Mead & White

Library for J. Pierpont Morgan, Esq., ca. August 1902

Graphite with wash

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library: the Architects' Model

After Morgan engaged McKim, Mead & White to design his Library in 1902, lead architect Charles Follen McKim developed several proposals (including one with a tall cupola) before arriving at the plan embodied in this plaster maquette. The model differs only in modest respects from the completed building. The two arched niches would remain empty; no sculptures were ever installed. Notably missing here are the marble lionesses that Edward Clark Potter would sculpt to flank the entry.

Maquette for J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, designed by McKim, Mead & White, ca. 1904 or later

Plaster

The Morgan Library & Museum Archives; ARC 2646

A Vision for Morgan's Library

In August 1902, as design development was in its final stages, Charles Follen McKim commissioned Hughson Hawley, a well-regarded architectural renderer, to create this evocative watercolor of the approved design. With its depictions of blue skies above, horses and carriages passing by, and fashionably dressed New Yorkers milling about, the drawing anticipated the way the completed building would appear in its residential context.

Hughson Hawley (1850–1936) for McKim, Mead & White

J. Pierpont Morgan’s Library, 1902

Watercolor

The Morgan Library & Museum; 1958.24

Inside the Bookman's Paradise

This longitudinal section, created late in the design process, depicts the Library’s three principal rooms. At left is the West Room (Morgan’s study), with its low bookshelves and space for the display of artworks. At center is the Rotunda, the main hall, with its highly decorated domed ceiling and ring of pilasters. At right is the East Room, the grand space in which much of Morgan’s book collection would be prominently displayed. A dotted line traces the position of a spiral staircase that begins at the cellar level.

The doorway at the immediate center leads to the North Room, which would become the office of Morgan’s librarian, Belle da Costa Greene. The antique stone doorframe is engraved with the motto Soli Deo Honor et Gloria (Glory and honor to God alone).

McKim, Mead & White (drafter unknown)

Library for J. P. Morgan Esq., Longitudinal Section, Looking North, 1905

Ink on linen

New-York Historical Society, McKim, Mead & White Architectural Collection